Abstract

The USAID/WASHplus project conducted a comprehensive assessment to understand consumer needs and preferences as they relate to increasing the uptake and consistent, exclusive, and correct use of improved cookstoves (ICSs) in Bangladesh. The assessment included household ICS trials, fuel and stove use monitoring, and consumers’ perceived value of and willingness to pay for ICSs. Results showed that cooks appreciated and liked the ICS, but that no models met consumer needs sufficiently to replace traditional stoves. Initially, many preferred ICSs over traditional stoves, but this preference decreased over the 3-week trial period. Complaints and suggestions for improvement fell into two general categories: those that can be addressed through fairly simple modifications to the stove design, and those more appropriately addressed through point‐of‐purchase consumer education and follow-up from service agents or health outreach workers. Most households using the ICS realized fuel use reductions, although these were lower than expected, partly because of continued parallel traditional stove use. When given the option to purchase the stoves at market value, only one of 105 households did so; however, a separate assessment showed that 80% of participants (12 of 15 households) preferred to keep the stove rather than receive a cash buyout at market value. This indicates that users value the ICS when acquisition barriers are removed and highlights the need for better financing options.

A growing evidence base links improved cookstoves (ICSs)—that is, cookstoves with demonstrably more efficient fuel use and lower emissions than traditional biomass stoves—with positive health and energy impacts (Mehta & Shahpar, Citation2004; Smith et al., Citation2011). This has focused attention on the best ways to influence household uptake and the consistent, correct, and exclusive use of ICS. Appropriately, a major concern is how to improve the stoves’ field performance and make them affordable, accessible, and appealing to the neediest consumers.

This study, undertaken by the USAID-funded WASHplus project,Footnote1 specifically responds to informational and methodological gaps in the knowledge base related to consumer preferences and willingness to pay for ICS. Cookstove literature is rife with studies documenting a low demand for or inconsistent and incorrect use of cookstoves (Chowdhury, Koike, Akther, & Miah, Citation2011; Ekouevl & Tuntivate, Citation2012; Gordon & Hyman, Citation2012; Miller & Mobarak, Citation2011; Mobarak, Dwivedi, Bailis, Hildemann, & Miller, Citation2012; Puzzolo, Stanistreet, Pope, Bruce, & Rehfuess, Citation2013). Many initiatives to increase the use of ICS build interventions around the often faulty assumption that people will do or buy something simply because it is good for them. In contrast, marketers assume people do and buy things that deliver the desired benefits at a price they are willing to pay. This study uses consumer market research techniques to better understand consumer preferences, attitudes, and behaviors in a market-based economy. This helps identify and assess how changing elements of the marketing mix (the “Ps” of product, price, place, and promotion/communications) impact customer behavior.

Consumer information is contextual and varies by consumer segment and location. Market research techniques often assess the interface of consumers and products, but are rarely used to promote clean cooking and ICS. This study addresses the dearth in consumer research data available for the Bangladeshi cookstove market and, more broadly, aims to adapt and refine accepted market research techniques for the cookstove sector. It is not an intervention study, but lays the groundwork for effective interventions by combining and refining research methods including product trials, actual fuel and stove usage monitoring, and willingness to pay based on real-life stove purchasing transactions. Findings can be used by stakeholders in Bangladesh to promote clean cooking and open the market to a new generation of ICS.

Objectives

Successful cookstove programs depend on identifying what consumers want from a cookstove and providing new stoves that meet those criteria. Accordingly, the objectives of this study were to determine the following:

Consumer preference (including actual stove usage)

Range of desired cookstove attributes including size, portability, stability, and functionality

What cooks and their families perceived as benefits of each particular ICS

Comparison of traditional and ICS with respect to desired attributes

Perceived barriers and dislikes with respect to consistent and correct use of each ICS

Desirable, feasible solutions to perceived barriers, either by modifying household behaviors or stove design, without sacrificing stove performance

Those characteristics, attributes, likes, and dislikes most persuasive to households, including cross‐cutting or abstract aspirational benefits.Footnote2

Effectiveness of various ICS

Consumer willingness to pay (for ICS)

An additional methodological objective was to refine market research tools to the ICS and clean cooking context, and to incorporate quantitative measures into this research.

Method

To achieve these objectives, investigators examined participants’ experience through repeated qualitative interviews and quantitative methods such as determining wood usage through Kitchen Performance Tests, and measuring household air pollution. Stove use monitoring sensors (SUMS) were used to objectively measure traditional and improved stove usage, and these results were compared with self‐reported use. Also, two approaches were used to determine perceived value and willingness to pay.

Trials of Improved Practice

Researchers applied Trials of Improved Practices (TIPs) to assess consumer preferences, barriers and facilitators to ICS adoption, and ICS usage. This involved asking “elicitation questions” (Middlestadt, Bhatacharyya, & Rosenbaum, Citation1996), which are semi-structured questions developed and validated to systematically identify barriers and motivators to change, including those factors most influential in spurring the purchase and consistent, exclusive, and correct use of ICS. This qualitative methodology invites households to interact with researchers and jointly identify, discuss, and resolve barriers to ICS use.

Formative field research was conducted in January and February 2013. Two areas of Bangladesh—Sylhet in the northwest and Barisal in the south—were purposively selected because they are representative of wood-burning areas of Bangladesh and also had active nongovernmental organizations willing to support community entry and study objectives. Households were eligible if they met the following screening criteria: primarily used wood for cooking, had at least four household residents, and had at least one child under 5. Investigators randomly selected 15 study households from the pool of eligible households in each of eight villages, for a total of 120 households.

Each selected household was randomly assigned one of five different imported ICS models (potentially, though not currently, available for distribution in Bangladesh) to test and was given detailed training on cookstove operation and maintenance. Investigators asked each cook to try the new stove under normal conditions for three weeks and to offer feedback at several junctures in this period.

During the trial, investigators invited households to identify, discuss, and seek viable solutions to any barriers to the consistent, correct use of the new ICS. Interviewers used semi‐structured questions to identify likes and dislikes about, barriers to, and motivators for ICS use. Investigators also asked households to use a range of criteria to compare cooking on the ICS to cooking on their traditional sunken-hole mud stove. Interviews were conducted on Day 1 (baseline), Day 3 (to determine initial preferences, use patterns, and other initial reactions, and to troubleshoot problems), and Day 21 (final).

All ICS models tested in this study were imported from elsewhere in South Asia; none were designed specifically for the Bangladesh market. Models included a single pot, built-in-place, rocket design stove (Envirofit Z3000); a single pot, portable, rocket design stove (EcoZoom Dura); a two-pot portable metal chimney stove (Prakti LeoChimney); a single-pot portable fan stove (Eco-Chula); and a single-pot portable natural draft stove (Greenway SmartStove). Figure shows the five models. All ICS models met a minimum of Tier 2 fuel efficiency using ISO IWA 11:2012 guidelines; this was then compared with the Tier 0 traditional baseline, which in Bangladesh consists of a sunken-hole mud stove.Footnote3 The only model available for purchase in Bangladesh at the time of the study, albeit in small quantities, was the Greenway; however, all five models had the potential to be manufactured and/or assembled in Bangladesh. Stoves were selected by characteristics (chimney/not, fan/not, portable/not), not by brand, to represent a range of stove types. An added benefit of using imported stoves with which consumers were not familiar was the avoidance of any influence of brand loyalty.

Fuel Use

Changes in fuel use quantities were measured using a three-day kitchen performance test (KPT; Bailis, Citation2007), widely acknowledged as the best currently available method for accurately estimating daily household fuel consumption. The KPT involved a cross-sectional study design with all of the 120 TIPs study households except three who declined to participate (23–24 households per stove type) and 23 control households (randomly selected from the pool of eligible TIPs households not selected for the trials). The sample size (20+ in each group) was designed to detect statistically significant differences in fuel use given the anticipated 35–40% reduction in ICS fuel use (compared with traditional stovesFootnote4) and the variability in fuel use measurements typically seen in KPT studies—the fuel use sample size requirements dictated the sample size for the TIPs trial (coefficient of variation in the 0.4–0.45 range). All potential household fuels (wood, crop residues, charcoal, kerosene) were weighed using Salter Brecknell Electro Samson digital hand-held scales (25 kg maximum with a resolution of 0.02 kg) at the beginning and end of three 24-hour monitoring periods. The control households were selected at random from the pool of remaining eligible households not yet selected for the study.

Households were asked daily about cooking stove and fuel usage, the number and type of meals prepared, and the number of people cooked for. They were also asked to maintain typical cooking patterns throughout the study. During the KPT study, researchers monitored air pollution and exposure in seven households for illustrative purposes. These results are not included in this report.

Actual and Reported Stove Usage

Two approaches were used to measure the extent to which households adopted the new stoves: self-reported use of stoves at the end of each 24-hour KPT monitoring period and SUMS. The SUMS temperature-logging sensors (iButton model DS1922T, manufactured by Maxim Integrated) were affixed to the stoves to collect data on how often the stoves were lit. SUMS were placed on all ICS, all traditional stoves in the control group, and on traditional stoves in a subset (51%) of the ICS homes. SUMS were also placed in 10 kitchens to measure ambient temperature. SUMS data was recorded for at least 10 days starting on the first day of the KPT. Table shows a summary of the methods employed by the investigation team.

Table 1. Summary of methods

Willingness to Pay

Two different innovative willingness to pay (WTP) assessments marked the completion of the stove trial. These were based on a review of previous methods used to assess WTP for improved cookstoves and discussions with experts, including TRAction grant recipients. The first assessment method modified the well-accepted Vickery auction,Footnote5 to simulate a marketplace rather than an auction. For this assessment, 105 households in seven villages were given the opportunity to purchase the study stoves at market rates in a bargaining exercise that included installment payment options. Using a defined script and form, interviewers described the process; if the respondent expressed interest in owning the stove, the interviewer opened the bargaining by giving the realistic market price of the stove (US$35–$70, depending on model), and invited the respondent to bargain as they would in a shop or market. The price reflected actual cost (estimated shipping, transport, and reasonable profit for two tiers of distribution), and was discounted for potential carbon credit cost reductions, and the fact that the stove was no longer new and no service would be offered for it. Interviewers had a bottom price they could accept (US$19–$54, depending on model), though it was not revealed. Scripted counteroffers brought the price closer to, but always above the bottom price. The interviewer also offered an option of five weekly payments based on the bottom price plus 20% interest. In the second assessment, investigators gave an ICS to all 15 households in a single village, then immediately offered each household cash to sell it back at the same bottom price accepted in the first assessment. This method was used for only one village because investigators assumed a high buy-back rate, which would have required interviewers to travel with large quantities of cash in a volatile context, and collect stoves from those who sold them back. (The study was conducted tumultuous months of early 2013, a time with extensive road violence, strikes and blockades.)

Findings

Consumer Preference

Overall, consumers reported liking the new stoves. This was a distinct indicator separate from whether or not they preferred the ICS to the traditional stove. These general reactions were common across stove types.

On the basis of their responses to the Day 21 survey, about two thirds (66%) of the study participants said food tastes the same when cooked on an ICS versus a traditional stove, with the others equally split between saying it was better (18%) or worse (16%). Respondents overwhelmingly felt the improved stoves used less fuel than their old stoves used, with almost three fourths of the group reporting fuel savings (72%). About a fifth of the participants thought the new stoves used more fuel.

When asked about differences in smoke produced by the ICS versus the traditional stove, most (72%) said the ICS produced less smoke. A few indicated no change (11%), and a small group (16%) reported more smoke. The results were basically the same when reported by husbands or wives.

When asked if the ICS had any impact on cooking pots, more than half the users (53%) felt the new stoves kept their pots cleaner, a few (13%) saw no impact, and a third (34%) reported it made the pots dirtier than the traditional stove. This finding was influenced by some users overfilling the ICS with wood to make flames visibly meet the cooking pot, thereby increasing soot deposition (and emissions).

A major obstacle to ICS use was slower cooking time, especially for long‐cooking items such as rice and daal. More than three fourths (77%) of respondents reported slower cooking time with an ICS compared with their traditional stoves, a fifth (20%) reported faster cooking, and a few (less than 3%) said cooking time was the same.

The most overarching complaint about all ICS included in the trial was their inability to cook large volumes of food in large pots; this was especially noted for the Prakti and Greenway cookstoves. Study participants reported compensating by adding more wood for extra fire power, which rendered some stoves less stable. As is common with other stove studies, participants were unaccustomed and/or unwilling to chop wood into small pieces, thus complaints were received about the size and angle of the wood opening. Traditional stoves in Bangladesh allow a “natural feed” of large wood pieces and other agrofuels and dungsticks (see Figure ); because the opening into the combustion chamber angles downward, the fuel naturally slides further into the combustion chamber as it burns. Consumers missed this feature on the new stoves, which have a horizontal fuel entry and require that fuel be manually pushed into the stove as it burns. Last, consumers found that excess ash collected in the stove and suggested a large tray for easy emptying. Some of the ash build-up resulted when excessive amounts of wood were burned in the stoves to make flames leap around the pot. In case of the Prakti stove, the major complaint was that the second pot was not effective for cooking. For the Greenway stove, a major complaint was that the stove was not stable, particularly with the large pots used to cook the family rice. Otherwise, complaints were relatively similar across all stove types.

Table summarizes the most common problems encountered across all the ICS and the suggested solutions from participants. The three suggestions that would compromise stove performance are listed with a strikethrough mark (the text is crossed-out); recommendations to address these problems are detailed in the discussion section.

Table 2. Common problems with ICSs and user-proposed solutions

In response to the open‐ended question, “What do you think about the stove?” asked after three weeks, a clear majority said it was cleaner, released less soot and smoke into the house, and used less firewood. Many of the participants offered the unprompted response that they enjoyed cooking on the stove, and almost a fifth said it looked nice. However, a small minority said their ICS emitted more smoke (12%), that it used more wood (10%), or that they did not enjoy cooking on the stove (18%).

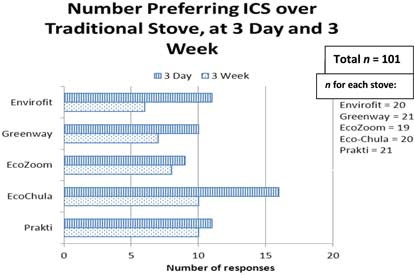

Thus, one surprising finding was the dramatic decrease in acceptance of ICS from Day 3 to Day 21. At Day 3, most households (56%) preferred their new stove to their old traditional cookstove. After 21 days, however, ICS preference dropped to 41%. The drop was especially pronounced for the Eco-Chula stove. Reporting indicated that people initially liked the Eco-Chula because it was portable and clean burning (especially valuable in Barisal where people cook in semi-enclosed areas without smoke hoods), but over time they resented having to chop wood into the small pieces required by the stove, and having to continuously sit by the stove and add wood rather than being able to multitask as they were accustomed. This was true to a lesser extent for all ICS; people reported they grew to dislike the ICS requirements for fuel preparation, changes in cooking patterns, and investigators’ request to use wood for the study (at a time of year when they might be using free leaf litter). Figure shows changes in preference for each ICS over the traditional stove from Day 3 to Day 21.

KPT and SUMS Findings

KPT and SUMS monitoring confirmed that all study households used the ICS each day of the KPT, but that the ICS did not fully displace traditional stoves in any household. Homes using four of the five ICS models (in parallel with traditional stoves) used 16% to 30% less fuel than the control homes during the KPT. It is interesting that SUMS data demonstrated that once the KPT field teams stopped visiting the homes daily, all groups, including the control group, showed a marked reduction in stove use, whether ICS or traditional, an example of the Hawthorne effect (observer bias).

The study successfully collected SUMS data from both ICS and traditional stoves in half the ICS households. During the KPT monitoring, in study homes with ICS, the average number of uses (cooking events) per day for ICS only ranged from 2.1 to 3.3, and the average daily use for traditional stoves ranged from 1.3 to 1.9. Table shows the combined daily average for all stove use during and after the KPT.

Table 3. Average (mean) number of stove uses per day for all stoves (traditional and ICS)

Table shows the percentage of total cooking events performed using ICS by household type, before and after the KPT. These tables demonstrate that after the KPT monitoring ended, the total number of daily cooking events decreased and a smaller portion of these were performed using the ICS.

Table 4. Proportion of all recorded cooking events performed by the ICS (by stove type)

Perceived Value and Willingness to Pay

Study participants valued certain ICS features, but dramatically undervalued the stoves’ monetary worth, generally estimating this at one half to one quarter of the calculated US$19–$54 value. Only 12 of the 105 study participants invited to purchase an ICS at market value (including options for installment payments) entered into negotiations, and only one participant actually purchased a stove, although a second nonstudy participant (the purchaser's landlady) also bought a stove.

Participants indicated they liked the various ICS and would have kept them if given for free or at a nominal cost. Both self-reported and objectively documented data indicated that ICS complemented rather than replaced traditional stoves. Householders acknowledged they were not ready to buy ICS at market prices for the following reasons:

The stove model was small and could not completely replace the primary stove

They wanted the stove for free or at a nominal price as a reward for study participation. Some noted in the winter they usually use free dry leafy biomass as fuel in special mud stoves constructed outside, and they supplied wood for the ICS at their own expense for the sake of the study.

They could not risk paying so much for an experimental model that would not be serviced after the study

They did not want to buy the stoves on installments because of added interest or loan service fees

The second methodology, used in 15 households, offered the stoves as gifts, and then offered a cash buyout at market value (US$19–$54). It is surprising that only three households chose the relatively significant cash option; the other 12 preferred to keep their stove. One of the three households had intended to keep the stove, but faced an expensive medical need, so reluctantly accepted the buyback offer.

Discussion

Stove Preferences

Respondents offered numerous suggestions for improving stoves, many of which provide valuable feedback to stove manufacturers. Being responsive to consumer input, however, does not require making all suggested modifications; some suggestions would be impossible to implement and/or render stoves less efficient or even dangerous. Recommendations fell into two general categories: those best addressed through stove design modifications to increase ease of use or appeal, and those more appropriately addressed through point-of-purchase consumer education and/or follow-up from service agents or health outreach workers.

For example, cooks used to traditional stoves often assume that they need to see flames, as more wood and flame equates with higher fire power for traditional stoves. Consequently, they may overfill an ICS with wood, decreasing the efficiency and increasing emissions. Consumer education needs to address this issue, ideally with in-person demonstrations.

The effects of targeted user education on the uptake, and consistent and correct use of ICS cannot be underestimated. If users do not understand how to use stoves optimally, stoves will not deliver key benefits or meet user expectations, and consumers will conclude that the higher purchase cost, extra effort to prepare wood fuel, and required modifications in cooking practices outweigh the benefits. All products depend on word-of-mouth promotion, particularly new products. If consumers are not happy with their personal cost-benefit returns from ICS, they will, at best, reduce ICS use and, at worst, spread negative publicity that lowers ICS adoption rates.

KPT and SUMS

The KPT and SUMS findings confirm the phenomenon seen in many ICS study households of continuing to use traditional stoves alongside the new stoves (Pine et al., Citation2011; Ruiz‐Mercado, Canuz, Walker, & Smith, Citation2013; Ruiz‐Mercado, Masera, Zamora, & Smith, Citation2011). This tendency resulted in lower than expected fuel savings and underscored the importance of better meeting all consumer needs.

Perceived Value and Willingness to Pay

Had investigators used only one method to assess WTP, the low number of households that entered into negotiations to buy an ICS (12 of 105), and the fact that only a single study home (and one nonstudy home) actually purchased an ICS would have led to the conclusion that households do not value ICS at market rates. The results of the second WTP assessment, however, led investigators to understand that participants valued the ICS enough to forgo its cash equivalent in exchange for its return. This suggests people value ICS when acquisition barriers were removed, although it could also demonstrate an endowment effect, the phenomenon where people ascribe more value to things merely because they own them (Roeckelein, Citation2006).

On the basis of the combined results, the investigators recommend financing options for ICS, including low payments over a longer period of time, with low interest rates. Also critical to the finance equation is emphasizing fuel savings; this has seasonal marketing implications as consumers will be more likely to purchase an ICS during months they ordinarily buy wood than during months they typically use leaf litter and other free agrofuel. Investigators observed that householders did not appear to calculate fuel savings into their WTP. While many showed great facility at calculating installment payments and interest rates, no similar calculations were noted regarding fuel savings over time to help finance the initial ICS cost. The Impact Carbon paper also published in this special issue (Beltramo, Blalock, Levine, & Simons, Citation2015) has specific lessons and recommendations around financing for improved cookstoves; while these are based on experiences elsewhere they should nonetheless be explored as appropriate and appealing options for Bangladesh.

Researchers speculate there may have been communication and perhaps even agreement about the stove testing, both within villages and sometimes among villages, with the objective of enabling participants to be gifted the stoves or purchase ICS at the lowest possible prices. Most notable was the uniformity of the participant valuation/price offering at a fraction of market cost, hovering at the equivalent of a few dollars; and far below other valuation exercises outside of the village context, poststudy, with other stakeholders. Field teams reported that participants communicated to interviewers that thought they should receive the ICS for free or at a highly subsidized price, based on their observations that both local and international nongovernmental organizations give social products away for free in Bangladesh. All of the organizations involved in the study were international and local nongovernmental organizations. The perception that this study was led by a rich international nongovernmental organization was exacerbated by institutional review board (ethical) consent procedures that required each household be informed the study was conducted by a U.S.-based nongovernmental organization.

The conduct and findings of the study help fill gaps in the current literature and best practice approaches to increase uptake, and consistent and correct use of ICS. Findings illustrate the importance of focusing on the complement of “Ps”—product, price, place, and promotion/communications—in the marketing mix, based on input from consumers. This includes modifying stoves to meet consumer demands, including addressing the stove/fuel dyad for proper use and consumer satisfaction (“product”); and focusing more attention on “pricing” and financing innovations to make products affordable and desirable, again with focus on the fuel/stove dyad to reinforce total cooking costs, not simply the price of cookstove acquisition. Study findings shed less light on “place,” although researchers found that nongovernmental organizations were not an accepted place or distribution mechanism for selling stoves at market price without financing. Nongovernmental organizations could, however, be appropriate for coordinating financing or group purchases, and this should be further explored. Last, findings inform “promotion,” which typically receives the most emphasis in stove programs, but often focuses on how ICS improve health and save money. The findings will allow for more focused promotion of stove attributes and aspirational benefits that Bangladeshi consumers value.

Possible Study Biases

The investigators attempted to minimize study biases, such as subject selection and reporting/recording bias, through careful training and monitoring of study procedures, data collection, and analysis. Any biases that were suspected or noted have been identified in this article. For example, the Hawthorne effect was clearly observed in this study as an increase in the frequency of both ICS and traditional stove use when researchers were present.

By recording actual stove use through SUMS, recall bias was documented and negated. Investigators suspect response bias in the WTP auction, during which field researchers reported discussion and collusion among participants to set low prices for ICS and to influence researchers to give the stoves as a participation incentive.

Recommendations and Conclusions

The study clearly showed that cooks appreciated and liked the ICS, although no models met consumer needs sufficiently to completely replace traditional stoves.

Because none of the currently available ICS models sufficiently met expressed consumer needs, further stove design improvements are suggested for the Bangladesh market; such improvements will require additional consumer preference testing. Household recommendations for design changes were shared with manufacturers, and several have made design changes to address identified problems.

Larger two-pot stoves with higher firepower are recommended for trial in Bangladesh to address user complaints that the second burner of the two-pot stove included in this trial did not burn hot enough. Of note, the WASHplus project conducted limited Controlled Cooking TestsFootnote6 on modified versions of these stoves in 2014 to gauge stove performance, and the higher firepower two-pot stove was well-liked by cooks. Because of participants’ seasonal dependence on free agrofuels, trialing of a mixed-fuel stove is also suggested; such testing is already underway in Bangladesh by one of the manufacturers included in this study.

In addition to stove modifications,Footnote7 the authors suggest educating consumers through point of purchase and other promotional materials, interaction with distributors and sales people, and health or other outreach activities. This educational component is essential for the consistent and correct use of ICS, which will improve consumer satisfaction, and increase word-of-mouth recommendations.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge their partners in this study, including Village Education Resource Center, DESH GORI, Institute of Development Affairs, and Berkeley Air Monitoring Group, who contributed directly to the KPT and SUMS sections of this report.

Notes

1The USAID-funded WASHplus project creates supportive environments for healthy households and communities by delivering high-impact interventions in water supply, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) and indoor air pollution.

2Aspirational strategies appeal to consumers’ psychological, social and/or economic hopes and goals, rather than their psychological, social and/or economic realities, based on the premise that emotions play as important a role in our purchase decision making as rationality (Hill, Citation2010).

3The International Standards Organization (ISO) International Workshop Agreement (IWA 11:2012 Guidelines for Evaluating Cookstove Performance) provides guidance for rating cookstoves on four key performance indicators: fuel use/efficiency, total emissions, indoor emissions and safety on a scale from Tier 0 (baseline) to Tier 4 (aspirational). ISO Technical Committee 285 on Clean Cookstoves and Clean Cooking Solutions (approved June 2013) is currently working to develop and approve voluntary international cookstove standards based on IWA 11:2012. For more information: http://www.cleancookstoves.org/technology-and-fuels/standards.

4Anticipated based on results for some of these and other similar intervention stoves in previous KPT studies from various parts of the developing world undertaken by the KPT researchers.

5The Vickrey auction has all participants write their bid and submit in secret. The highest bidder wins the right to purchase, but the price is determined by the second highest bid. With this mechanism, the participants are provided an incentive to reveal their true valuation because they must buy the good if their bid wins the auction. Another well-accepted procedure is known as the BDM procedure introduced by the authors Becker, DeGroot and Marshak. In BDM, every participant simultaneously submits an offer price to purchase a product. A sale price is randomly drawn from a distribution of prices. The bidders whose bids are greater than the sale price receive a unit of the good and pay an amount equal to the sale price (Breidert, Hahsler, & Reutterer, Citation2006).

6Controlled Cooking Tests consist of real food prepared by real cooks in a controlled setting.

7ICS currently being disseminated in Bangladesh often include cement chimneys; more consumer behavior should be studied around chimneys, as well as experimentation and innovation around chimney design, particularly to allow for easier cleaning. Chimneys can be a very effective way of channeling smoke away from the cook, as long as they are well maintained. However, smoke can easily re-enter the kitchen through windows and without proper maintenance, smoke will back up into the kitchen. Bangladeshi homes may be particularly at risk; there is not an established culture of chimney maintenance in Bangladesh and for some houses (e.g., those with a thatched roof), there is really no way to clean a cement chimney properly. As such, exposure monitoring should be undertaken for chimney stoves considered for promotion.

References

- Bailis, R. (2007). Kitchen performance protocol: Version 3.0. Retrieved from http://cleancookstoves.org/technology-and-fuels/testing/protocols.html

- Beltramo, T., Blalock, G., Levine, D. I. & Simons, A. M. (2015) Does peer use influence adoption of efficient cookstoves? Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Uganda. Journal of Health Communication, 20(Suppl 1), 55–66.

- Breidert, C., Hahsler, M. & Reutterer, T. (2006). A review of methods for measuring willingness-to-pay. Retrieved from http://michael.hahsler.net/research/wtp_innovative_marketing2006/wtp_breidert_hahsler_reutterer_preprint.pdf

- Chowdhury, M. S. H., Koike, M., Akther, S. & Miah, M. D. (2011). Biomass fuel use, burning technique and reasons for the denial of improved cooking stoves by Forest User Groups of Rema-Kalenga Wildlife Sanctuary, Bangladesh. International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology, 18, 88–97.

- Ekouevl, K. & Tuntivate, V. (2012). Household energy access for cooking and heating: Lessons learned and the way forward. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Gordon, J. & Hyman, J. (2012). The stoves are also stacked: Evaluating the energy ladder, cookstove swap-out programs and social adoption preferences in the cookstove literature. Journal of Environmental Investing, 3, 17–41.

- Hill, D. (2010). Emotionomics: Leveraging emotions for business success. London, England: Kogan Page.

- Mehta, S. & Shahpar, C. (2004). The health benefits of interventions to reduce indoor air pollution from solid fuel use: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Energy for Sustainable Development, 8, 53–59.

- Middlestadt, S. E., Bhattacharyya, K., Rosenbaum, J., Fishbein, M. & Shepherd, M. (1996). The use of theory based semistructured elicitation questionnaires: Formative research for CDC's Prevention Marketing Initiative. Public Health Reports, 111(Suppl 1), 18–27.

- Miller, G. & Mobarak, A. (2011). Intra-household externalities and low demand for a new technology: Experimental evidence on improved cookstoves. Stanford, CA: Stanford University.

- Mobarak, A., Dwivedi, P., Bailis, R., Hildemann, L. & Miller, G. (2012). Low demand for non-traditional cookstove technologies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109, 10815–10820. doi:10.1073/pnas,1115571109

- Pine, K., Edwards, R., Masera, O., Schilmann, A., Marron-Mares, A. & Riojas-Rodriguez, H. (2011). Adoption and use of improved biomass stoves in rural Mexico. Energy for Sustainable Development, 15, 176–183.

- Puzzolo, E., Stanistreet, D., Pope, D., Bruce, N. & Rehfuess, E. (2013). Factors influencing the large-scale uptake by households of cleaner and more efficient household energy technologies. London, England: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London.

- Roeckelein, J. E. (2006). Elsevier's dictionary of psychological theories. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier.

- Ruiz‐Mercado, I., Canuz, E., Walker, J. L. & Smith, K. R. (2013). Quantitative metrics of stove adoption using stove use monitors (SUMs). Biomass and Bioenergy, 57, 136–148.

- Ruiz‐Mercado, I., Masera, O., Zamora, H. & Smith, K. (2011). Adoption and sustained use of improved cookstoves. Energy Policy, 39, 7557–7566.

- Smith, K., McCracken, J., Weber, M., Hubbard, A., Jenny, A., Thompson, L., … Bruce, N. (2011). Effect of reduction in household air pollution on childhood pneumonia in Guatemala (RESPIRE): A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 378, 1717–1726.