Abstract

This article describes the development of standard operating procedures (SOPs) for social mobilization and community engagement (SM/CE) in Sierra Leone during the Ebola outbreak of 2014–2015. It aims to (a) explain the rationale for a standardized approach, (b) describe the methodology used to develop the resulting SOPs, and (c) discuss the implications of the SOPs for future outbreak responses. Mixed methodologies were applied, including analysis of data on Ebola-related knowledge, attitudes, and practices; consultation through a national forum; and a series of workshops with more than 250 participants active in SM/CE in seven districts with recent confirmed cases. Specific challenges, best practices, and operational models were identified in relation to (a) the quality of SM/CE approaches; (b) coordination and operational structures; and (c) integration with Ebola services, including case management, burials, quarantine, and surveillance. This information was synthesized and codified into the SOPs, which include principles, roles, and actions for partners engaging in SM/CE as part of the Ebola response. This experience points to the need for a set of global principles and standards for meaningful SM/CE that can be rapidly adapted as a high-priority response component at the outset of future health and humanitarian crises.

On November 7, 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared the end of the 2014–2015 Ebola virus disease outbreak in Sierra Leone. As of this date, there were 8,704 confirmed cases, 3,589 confirmed deaths, and 5,122 suspected cases, as well as 4,051 discharged Ebola survivors in Sierra Leone (National Ebola Response Center, Citation2015). Although significant, the total number of Ebola cases was far fewer than some initial predictions (Meltzer et al., Citation2014).

Disease modeling of the West Africa Ebola epidemic and anthropological studies of previous smaller scale outbreaks have shown that social and behavioral change has played an instrumental role in curtailing Ebola outbreaks (Fast, Mekaru, Brownstein, Postlethwaite, & Markuzon, Citation2015; Hewlett & Hewlett, Citation2008). It appears that social mobilization efforts in Sierra Leone played a role in supporting and accelerating positive behavior change. A series of knowledge, attitudes, and practices surveys conducted in Sierra Leone between August 2014 and July 2015 suggested that efforts to improve prevention and treatment knowledge; reduce misconceptions and stigma; increase acceptance of safe, dignified medical burials (SDMB); and promote other safe practices related to Ebola were largely successful over time (Jalloh et al., Citation2016).Footnote1

A range of terminology is used to describe work with communities to achieve individual and/or collective change. UNICEF (Citation2015) uses the term social mobilization to describe a process that engages and motivates a wide range of partners at national and local levels to raise awareness of and facilitate change around a particular development objective. Community engagement generally refers to a collaborative, relationship-building process among individuals and groups that helps move communities toward change (Head, Citation2007; Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, Citation1998). In this article, both terms—social mobilization and community engagement (SM/CE)—are used to describe the broad spectrum of activities undertaken to support communities in determining and improving their own health and well-being during the Sierra Leone Ebola outbreak.

In Sierra Leone, although the Ebola response had a strong evidence-based National Communications Strategy to guide SM/CE activities and at-scale examples of good practice on the ground, the operational structures to effectively link strategic goals to practice were weak within the response architecture. Moreover, given the large number of partners involved in SM/CE with varying understandings and operationalizations of SM/CE, there was a pressing need to standardize approaches, processes, and procedures.

As the epidemic evolved, it became clear that standard operating procedures (SOPs) for SM/CE could help bridge the gap between strategy and practice and address identified weaknesses in the quality, coordination, and integration of SM/CE activities within the broader response. This article aims to (a) explain the rationale for a standardized approach to SM/CE during the Ebola outbreak, (b) describe the methodology used to develop the resulting SOPs, and (c) discuss the implications of the SOPs for future outbreak responses.

Background

In July 2014, in response to the spread of Ebola, the government of Sierra Leone declared a national health emergency, established the Emergency Operations Center within the Ministry of Health and Sanitation (MOHS), and released the Sierra Leone Accelerated Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak Response Plan (WHO, 2014a). SM/CE was not historically part of the formal humanitarian cluster system coordinated by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in emergencies (Dubois & Wake, Citation2015). However, given the nature of this health emergency, the national response plan identified social mobilization/public information as one of its four pillars,Footnote2 with the objective “to create public awareness about Ebola, the risk factors for its transmission, its prevention and control” (WHO, Citation2014b).

The response plan paved the way for the development of the National Communications Strategy for Ebola Response in Sierra Leone. The National Communications Strategy was designed using baseline findings from a knowledge, attitudes, and practices survey conducted by FOCUS 1000, UNICEF, and Catholic Relief Services in August 2014 (Republic of Sierra Leone, Citation2014). Adopted in September 2014, it provided the basis for the National Social Mobilization Pillar (SM Pillar) structure and performance indicators for the remainder of the response.

By the end of September 2014, two months after WHO had declared a “public health emergency of international concern” (WHO, Citation2014b), and with cases continuing to rise, the Emergency Operations Center was reconfigured as the National Ebola Response Center, a separate entity from MOHS. The original four pillars of the response were expanded to seven, separating social mobilization and media and communications into two distinct pillars.Footnote3

The SM Pillar was led by the MOHS Health Education Department (MOHS-HED) with UNICEF acting as co-lead. The SM Pillar consisted of approximately 50 international, national, and local partners early in the response, but by September 2014 it had consolidated to 15–25 active participants at national and district levels.Footnote4 The main function of the National SM Pillar was to coordinate partners and focus on community awareness and behavior change, including measuring and reporting on key performance indicators.Footnote5 Functions related to managing public media (e.g., press releases) were assumed by the media and communications pillar. At the district level the national response format was replicated within the District Ebola Response Centers (DERCs), or “command centers,” as they were also known. The district SM Pillars were chaired by the District Health Management Teams (DHMTs) and co-chaired by either UNICEF or a nongovernmental organization partner. However, the institutional structure for the district SM Pillar was not always clear, especially in the early stages.

As the Ebola outbreak evolved in Sierra Leone, the response experienced two fundamental shifts in its approach to SM/CE. First, within the response itself, SM/CE shifted from being a relatively low priority to taking on a more central role. The initial response effort focused on containment of the virus through military- and police-enforced bylaws and quarantine and later on scale-up of temporary treatment facilities and establishment of other supply-side services and logistics. The heavy emphasis on case isolation and contact tracing in the beginning of an Ebola outbreak is crucial, especially within the first 24–48 hours (Benowitz et al., Citation2014). However, given the spread of the virus in multiple districts by August 2014, such isolation, surveillance, and contact tracing efforts were not sufficient to halt the transmission chain and reverse the epidemiological trend. As the outbreak accelerated, and given the limitations of clinical approaches and weak local systems, understanding of the importance of community engagement grew, and pressure increased for SM/CE to be central to Ebola prevention and control (Abramowitz et al., Citation2015).

Second, over time there was a shift in response emphasis from awareness raising/health education to deeper, dialogic community engagement approaches. Early on, SM/CE activities focused on raising awareness of the key signs and symptoms of Ebola, key prevention and health-seeking behaviors, and dos and don’ts. Although these messages remained relevant throughout the outbreak, the limitations of broad one-way information campaigns were soon revealed. Messages quickly became outdated or less relevant as the epidemic accelerated and the response shifted course. One-way communications channels (megaphones, posters) did not facilitate listening and were much less effective for communicating with and understanding communities in an atmosphere of heightened tension and fear. It became clear that messages and approaches needed to be adapted over time and targeted to specific groups to reach those with different communication needs.Footnote6

Early messages emphasizing that there was no cure for Ebola led to community confusion about the usefulness of seeking early treatment and further dampened demand for the limited services that were available (Dubois & Wake, Citation2015). Dialogue with communities revealed their concerns, lack of trust and variable understanding and perceptions of other services, such as SDMB and surveillance, signaling a need to better nuance messages accordingly. To build trust and create more meaningful two-way communications, better linkages were needed between the SM/CE demand-side activities and these supply-side services.

These shifts in the response were largely driven from the ground. Dialogic community engagement approaches, through local implementers, were under way from the earliest months of the outbreak. By November 2014, the Social Mobilization Action Consortium (SMAC) of nongovernmental organization implementers was mobilizing across the country at scale (SMAC, Citation2015).Footnote7 However, the focus of these and other groups on local structures and community dialogue within individual communities was initially not fully understood or appreciated across the response compared to more immediate, visible activities, such as media campaigns and urban poster distributions. Over time, the response recognized the need to move beyond top-down health messaging and draw on best practices of organizations already working at the community level.

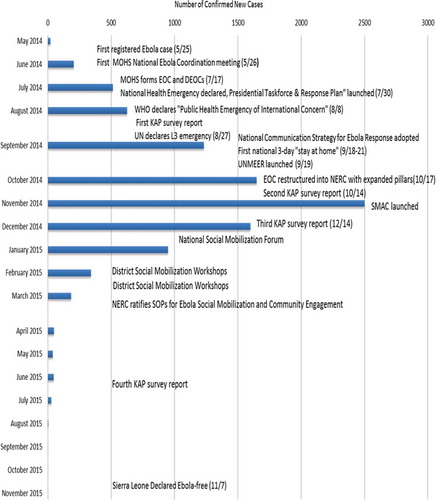

In early December 2014, for the first time since the start of the outbreak, new case numbers started dropping (WHO, Citation2015b; see ).Footnote8 By January, there was growing recognition that SM/CE would be central to effectively reaching zero Ebola and that operational improvements would be needed to achieve the goals set out in the National Communications Strategy. On January 30, 2015, MOHS-HED and UNICEF, with SM Pillar partners, convened a one-day national forum to define this shift in operational plans. Participants recognized the need for more sophisticated community engagement approaches rather than simple health messages. Given the changing epidemiology at the time, participants agreed on the need for improvements in rapid response to new localized outbreaks as well as approaches to avoid complacency in low-prevalence areas. In response to recognized operational weaknesses, the forum agreed on a three-point plan: to (a) improve the quality of SM/CE activities, (b) strengthen coordination of SM/CE partners, and (c) achieve integration of SM/CE efforts across all pillars of the response.

Fig. 1. Key events and social mobilization and community engagement milestones within the Sierra Leone Ebola epidemic. MOHS = Ministry of Health and Sanitation; EOC = Emergency Operations Center; DEOC = District Emergency Operations Center; WHO = World Health Organization; KAP = knowledge, attitudes, and practices; UN = United Nations; L3 = Level 3 (highest level emergency in the UN system); UNMEER = United Nations Mission for Ebola Emergency Response; NERC = National Ebola Response Center; SMAC = Social Mobilization Action Consortium; SOPs = standard operating procedures.

Methodology

Building on the agreements in the national forum, and using data from the baseline and second knowledge, attitudes, and practices surveys, a series of district workshops were conducted in February and March 2015. Based on confirmed cases registered in the weeks of January 28 and February 4, 2015, a geographic spread of seven districts with recent confirmed cases was selected: Western Area Urban and Western Area Rural, Port Loko, Kambia, Moyamba, Tonkolili, and Bombali (WHO, Citation2015b, Citation2015c).Footnote9

In each district, participants included community mobilizers; members from SM/CE implementing partners (IPs; typically community-based organizations and nongovernmental organizations); representatives from district-level survivor organizations, Islamic and Christian religions institutions, and local traditional healer associations; representatives from international agenciesFootnote10 ; and district representatives from the other response pillars, including surveillance, case management, burials, and psychosocial support. The workshops were co-convened by MOHS-HED and the respective DHMTs. On average, in each district approximately 40 participants from at least 20 organizations attended each workshop, for a total of approximately 250 participants. In the final planning sessions, Paramount Chiefs from each chiefdom or their appointed representatives also joined, except in the case of Western Area.Footnote11

The two-day workshops were structured to identify and address gaps in order to achieve the three goals of improved coordination, strengthened quality, and better integration of SM/CE activities with supply-side services. Participants presented their approaches, lessons, and experiences in a gallery walk format. This was followed by a card-sorting exercise in which groups synthesized what was working, what was not working, and why to distill common good practices and areas for improvement across their programs and operations.

Geographical micromapping of community mobilizers at the chiefdom level allowed participants to visualize the reach of various partners in terms of mobilizers physically based in communities. Mobilizer micromapping continued after the workshops, with partners providing specific details, as a requirement for SM Pillar participation under the new SOPs. On the second day, participants worked with Paramount Chiefs to develop draft action plans for each chiefdom focused on how to implement agreed improvements.

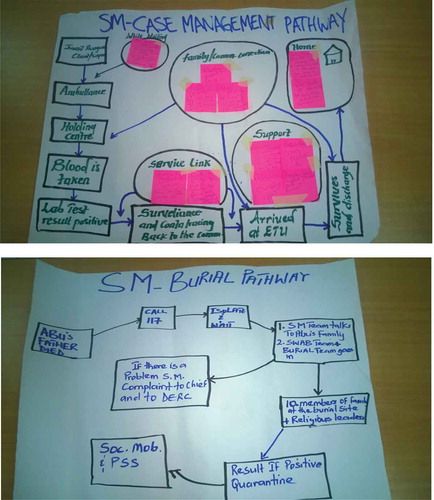

Applying a user-centered design methodology, participants developed service journey maps to explore shared understandings of the needs of community members at each step of their journey through the Ebola service pathway (see ). Participants broke into five groups, each representing a different response service: case management, SDMB, surveillance/contact tracing, quarantine, and psychosocial support. Participants then visually mapped their understanding of how a community member and her family interacts with different frontline service providers at the community level. At each stage of the journey, groups considered gaps in services and opportunities for mobilizers to support service providers to better meet community needs. Using these maps, groups identified procedures, steps, and lines of communication that could create better feedback loops between communities and Ebola service providers.

The best practices, coordination mechanisms, and new operational models proposed in the workshops were synthesized and codified into a draft SOP that was reviewed and further developed by SM Pillar members at national and district levels. The National Ebola Response Center approved the final SOPs on March 20, 2015, and they were accepted by partners shortly thereafter.

Findings

synthesizes key themes that emerged from the workshops with respect to improved quality, coordination, and integration.

Table 1. What is working and not working? Synthesis from social mobilization and community engagement district workshops

Workshop participants identified challenges associated with weak pillar leadership, including a lack of clarity and institutional home for SM/CE at the district level and poor on-ground coordination. Participants highlighted low attendance at district SM Pillar meetings, poor monitoring systems resulting in low levels of weekly reporting, and lack of a two-way information flow between IPs and response authorities. The discussion also unearthed examples of strong local coordination and integration between and across stakeholders, including communities, IPs, and DHMTs.

Participants highlighted tension between IPs sometimes competing to carve out their own turf. In rural areas, lack of coverage in the hardest to reach and most vulnerable communities was cause for concern. Several Paramount Chiefs raised concerns that some IPs were operating in their chiefdoms without their knowledge.

The workshops highlighted considerable differences in systems, structures, processes, and incentives between IPs. Micromapping of mobilizers resulted in participants identifying widely varied definitions of community mobilizer. Some IPs had trained community members with simple messages for one or two days as unsupervised volunteers who could not be easily contacted. Other IPs had fully trained,Footnote12 full-time mobilizers who were part of functioning networks with daily work schedules. Particularly in Western Area, participants discussed lack of consistency in monetary and nonmonetary incentives for mobilizers, which led to tensions among IPs and between IPs and communities.

Participants consistently identified a lack of trust as the key barrier to effectively engaging with communities and trust building as the most important element of their work. Discussions about the most effective ways to build trust identified the need for two-way dialogue through local residents; constant adapting of messages and strategies to respond to the evolving situation; targeted approaches that could reach specific groups or tackle specific perceptions; and networks of local mobilizers with adequate and relevant training, support, and supervision and with clear linkages to service providers and DERCs. Participants noted that outside mobilizers (e.g., those based in district towns rather than at the chiefdom or community level) were much less effective than those living within communities.

Discussions often focused on community responses to the Ebola response, not to the outbreak, and the adverse reactions that resulted when services did not meet community needs and expectations. Lack of trust was framed not only in terms of community disbelief in biomedical facts but more often in terms of community mobilizer difficulties in negotiating their roles as mediators between response authorities and communities. Along with the widespread belief that Ebola was a way for government and international agencies to make money (“Ebola business”), participants discussed dilemmas associated with acting as “representatives” of a response that did not always live up to its promises.

Participants described the challenges of fielding questions about response providers from community members, such as why the ambulances did not come on time, why traditional leaders were not properly consulted before a quarantine, why the messages changed from not eating bush meat to not washing dead bodies, and others. They also noted community concerns, for example, that ambulances were not being adequately disinfected and could be a source of infection; that male burial teams were not acting with proper respect, especially with regard to deceased women and societal heads; and that fumes from chlorine spray could suffocate patients and result in death. They noted that a mobilizer’s ability to maintain legitimacy and trust was in large part dependent on community experience with other aspects of the response as well as the mobilizer’s access to up-to-date, correct information. Some participants questioned how they could maintain independence from military operations, which they felt intimidated communities. Participants also noted difficulties in encouraging people to call local authorities in case of a sickness or death when this could result in being quarantined with little or poor-quality food and water supplies.

The pathway-mapping exercises revealed roles that community mobilizers were already playing beyond prevention and behavior change. Mobilizers were frequently among the first people called by families with sick members or deaths, often directly calling in these alerts to the DERCs.Footnote13 At the community level, mobilizers were frequently asked to take on additional tasks by frontline service providers because of their trusted roles. Some districts, such as Port Loko, had started to formalize mobilizer engagement within hot spots, with mobilizers, surveillance officers, and others operating as a single surge team. However, this was not happening consistently. Community mobilizers operated semi-formally within the space between communities, traditional leaders, and the formal response authorities. Participants noted that mobilizer roles and strengths were sometimes overlooked by the service provision pillars. Mobilizers were often aware of relevant community concerns but had few formal channels for sharing this information back to the other pillars. Because of the perceived lack of attention and priority afforded SM/CE, many IPs struggled to gain visibility and to explain the importance of their work. Many felt that SM/CE was not seen as technical or scientific, and this led to the perception that it was undervalued compared to the biomedical response.

SOPs

Information gathered in the workshops was used to develop the SOPs, which provide operational guidance on the structure and conduct of SM/CE activities. The SOPs reinforce overall institutional authority of MOHS-HED for ensuring that SM/CE activities are undertaken in accordance with the SOPs. The SOPs resolved confusion at the district level by clearly identifying DHMTs as the lead line agencies with functional links to the DERCs. In terms of the conduct of SM/CE, the SOPs are divided into three key sections addressing coordination, quality, and integration: (a) responsibilities of IPs, (b) prevention and behavior change, and (c) support roles in community Ebola service delivery.

Addressing Coordination: Responsibilities of IPs

The section on responsibilities of IPs addresses coordination challenges by articulating the minimum requirements for participation in the SM Pillar. Under the SOPs, IPs are required to register with the DHMT and consult with Paramount Chiefs and other local leaders to get approvals prior to undertaking activities. The DHMT can require adjustments to proposed locations of activities to avoid duplication and/or address gaps in geographic coverage. Registered IPs are required to submit a completed Mobilizer Mapping Template listing the names and locations of all mobilizers and their supervisors, to attend the weekly district planning meetings, and to submit the Weekly Reporting Form. These minimum requirements provided a framework for ensuring joint accountability across a wide range of partners.

The SOPs set minimum standards for IPs on selection, recruitment and training of mobilizers, providing for their safety and security, and incentives. IPs should consult local leaders and communities when recruiting mobilizers, ensure gender balance, and prioritize Ebola survivors if they express a willingness to participate. To address trust building and oversaturation of external people in hot spot communities, the SOPs recommend selecting mobilizers who are active, trusted people already living in the community, with outsiders deployed only in supportive roles. Each IP is responsible for ensuring that his or her staff and mobilizers are trained in accordance with the SOPs, have adequate information and supervision, and follow local bylaws and security protocols.

One of the more contentious issues raised in the workshops related to variations in incentives and payments to mobilizers. The SOPs specify that incentives should be provided as part of a package of training and supervision only to mobilizers who are working according to structured work plans. The SOPs advise IPs at the district level to discuss and align on mobilizer incentives, taking care to avoid setting unsustainable expectations and ensuring timely payment. The SOPs specify that community members must not be paid to attend meetings in their own communities or compensated for following Ebola-safe guidelines or bylaws, as these are required voluntary actions for ending Ebola transmission.

Improving Quality: Prevention and Behavior Change

The section on prevention and behavior sets out minimum standards of practice for SM/CE. The SOPs guide IPs to consider communities as experts in their own culture who should be adequately consulted and to work through existing community structures. Approaches that engage communities to analyze their own situations and develop their own action, such as Community-Led Ebola Action (CLEA), are recommended (SMAC, Citation2014).Footnote14 Although it is noted that megaphones and loudspeakers may be appropriate in limited situations, the SOPs identify dialogic, two-way communications methods as most appropriate, with print materials and awareness raising playing a supportive role. The SOPs note the importance of not bringing stigma or undue attention to those affected by Ebola, facilitating community discussion to support survivors who have returned home, and addressing discrimination and rumors about survivors and affected families. They advise specific inclusion of women, children and vulnerable groups, people living with HIV, and those with special needs.

The SOPs specify that all IPs are required to follow the MOHS approval process for new information, education, and communications materials to ensure consistency. They encourage the use of up-to-date quantitative and qualitative research in the design of new materials and messages. Subsections on child protection and psychosocial support stipulate that all IPs must adopt a clear standard referral process for referring children affected by Ebola to appropriate services.

Integrating With Supply-Side Services: Support Roles in Community Ebola Service Delivery

The section on SM/CE support roles in service delivery aims to address issues associated with poor feedback loops and lack of trust between communities and service providers. This section synthesizes the actions identified in the workshop service pathway mapping. Mobilizers help frontline service providers enter and operate smoothly in communities. This includes being at the site ahead of ambulance, surveillance, contact tracing, swab, quarantine, and burial teams to provide information and support while communities await help, presence during visits, and follow-up to gather community feedback.

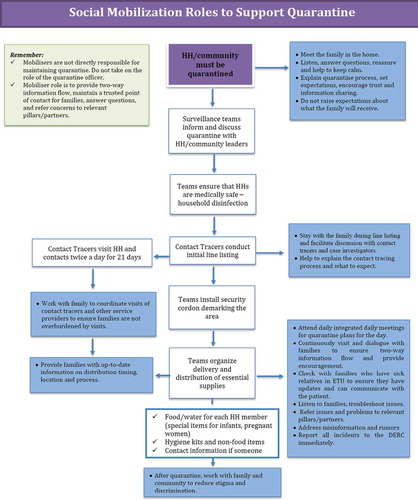

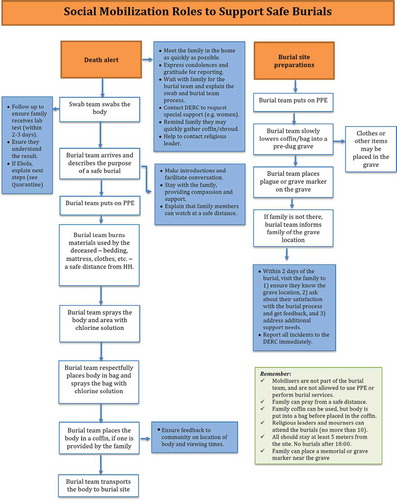

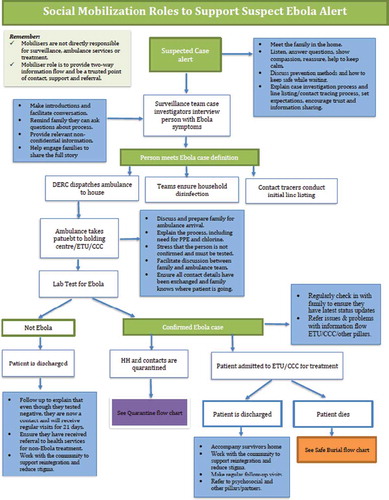

The final guidance for mobilizers is summarized in , , and . The SOPs identify roles and steps for mobilizers to support (a) case management teams, (b) surveillance and contact tracing teams, (c) quarantine officers, and (d) SDMB teams. For case management, the SOPs outline specific activities before, during, and after ambulance team arrival and during and after a patient’s admittance into an Ebola Treatment Unit. Similarly, the SOPs specify ways in which mobilizers can help surveillance officers and contact tracers gain community entry and trust, assisting before, during, and after these visits. During quarantine, mobilizer roles include keeping up dialogue with quarantined families so that they understand why they are quarantined and the risks posed if they leave quarantine. Finally, the SOPs set out the specific roles mobilizers play to ensure that death alerts are called and the communications roles they play before, during, and after burial team arrival. In general, mobilizers play a linking role at the community level, answering questions, providing advice, relaying information, and maintaining a trusted point of contact for families if they experience problems. The SOPs codify and formalize these roles as critical elements of an integrated response.

Fig. 2. Example service journey maps for case management and burial services developed during the Port Loko workshop.

Fig. 3. Roles for mobilizers to support surveillance and case management. HH = household; DERC = District Ebola Response Center; ETU = Ebola Treatment Unit; CCC = Community Care Center; PPE = personal protective equipment.

Conclusions

The Sierra Leone experience points to the need for a set of global principles and standards for meaningful SM/CE that can be rapidly adapted as a high-priority response component at the outset of future health and humanitarian crises. Rather than being at the periphery of such responses, SM/CE should take center stage in providing cross-cutting complementarities from the start and be fully integrated into the global architecture for humanitarian and other emergencies. Better institutionalization and clear standards of practice will encourage the use of rigorous social science to develop and monitor SM/CE programs. SOPs will help ensure that crisis responses recognize the importance of understanding communities and individuals as agents of their own change rather than passive recipients of messages and services.

The fact that behavior change is a process that can take time, coupled with pressure to produce immediate results in terms of disease containment, can lead to SM/CE inadvertently taking a backseat to biomedical and service delivery aspects of health emergencies. In Sierra Leone, the SM Pillar was the last of the pillars to adopt SOPs, which were not available until late March 2015, about 4 months after the Ebola epidemic had peaked. Perhaps this is unsurprising: Unlike case management or contact tracing, to which SOPs have always been integral, SOPs for SM/CE were not immediately prioritized as a need. There was perhaps a sense that everyone can do social mobilization or that SM/CE does not require technical understanding, training, and support. Ideally, the SOPs would have been available at the beginning of the outbreak in order to influence the practice, structure, functions, and resourcing of the SM Pillar from the outset.

Although improved operational standards are necessary, they will not be sufficient on their own. Tools and guidance can only be as effective as the systems, capacities, and resources that support them and translate them into practice. In addition to the development of global standards, SM/CE activities must also be properly resourced and prioritized as part of preparedness and response plans. Rigorous assessment of the outcomes and value for money of high-quality social mobilization in the West Africa Ebola epidemic vis-à-vis other response options could be an important first step. At the same time, further analysis of the impact of the SOPs in the final months of the epidemic in Sierra Leone will help determine how they were used in practice.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for contributions from the following critical reviewers: Samuel Sesay (Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation); Roeland Monasch, Kshitij Joshi, and Rafael Obregon (UNICEF); Lucille Knight (formerly of UNICEF); Amanda Crookes (Handicap International); Patricia Moscibrodzki (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai); and Fatou Wurie (Evidence for Action-MamaYe Campaign).

The development of the Sierra Leone Standard Operating Procedures for Social Mobilization and Community Engagement was a collaborative process including input from the following key partners: Ministry of Health and Sanitation and District Health Management Teams; United Nations agencies (UNICEF, United Nations Mission for Ebola Emergency Response, World Health Organization, United Nations Population Fund, International Labour Organization); Social Mobilization Action Consortium composed of partners including BBC Media Action, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Focus 1000, GOAL, and Restless Development; ABC Development; Action Aid; Action Contra la Feme; BRAC; Catholic Relief Services; Caritas; Care International; CADA; CAWeC; Child Welfare Society; CHRISTAG; Concern; Conservation Alliance; eHealth; ENGIM; Help SL; Evidence for Action-MamaYe Campaign; FAWE; First Response Liberia Ambulance; Forut; Handicap International; Health for All Coalition; International Rescue Committee; ISLAG; KADDRO; Johns Hopkins University; Médecins Sans Frontières; NRD-SL; Oxfam; Partners in Health; People’s Advocacy Network; Plan; Real Women; RODA; Save the Children; Sierra Leone Red Cross and International Federation of the Red Cross; UPHR-SL; World Hope International; Voice of Women; World Vision; and others.

Notes

1 For instance, comprehensive Ebola knowledge increased from 39% in August 2014 to 69% in July 2015 (Focus 1000, Citation2014). During this same period discriminatory attitude decreased from 95% to 41%, and hand washing with soap and water (to avoid Ebola infection) increased from 66% to nearly 90%. Similarly, the proportion of respondents objecting to SDMB for a deceased family member decreased from more than 30% in October 2014 to just 11% in December 2014, the period when the upward Ebola epidemiological curve stalled and began a slow downward trend going into January 2015 (Jalloh et al., Citation2016).

2 The initial four pillars under the Emergency Operations Center were (a) coordination/finance/logistics; (b) epidemiology/surveillance and laboratory; (c) case management, infection control, and psychosocial support; and (d) social mobilization/public information.

3 The expanded seven pillars under the National Ebola Response Center were (a) surveillance, contact tracing, and labs; (b) case management and infection prevention and control; (c) logistics and supplies; (d) SDMB, including management of ambulances; (e) child protection, psychosocial support, and survivors; (f) media and communication; and (g) social mobilization.

4 Organizations involved in the SM Pillar included MOHS and District Health Management Teams; United Nations agencies (UNICEF, United Nations Mission on Emergency Ebola Response, World Health Organization, United Nations Population Fund, International Labour Organization); Social Mobilization Action Consortium composed of partners BBC Media Action, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Focus 1000, GOAL, and Restless Development; ABC Development; Action Aid; Action Contra la Feme; BRAC; Catholic Relief Services; Caritas; Care International; CADA; CAWeC; Child Welfare Society; CHRISTAG; Concern; Conservation Alliance; eHealth; ENGIM; Help SL; Evidence for Action-MamaYe Campaign; FAWE; First Response Liberia Ambulance; Forut; Handicap International; Health for All Coalition; International Rescue Committee; ISLAG; KADDRO; Johns Hopkins University; Médecins Sans Frontières; NRD-SL; Oxfam; Partners in Health; People’s Advocacy Network; Plan; Real Women; RODA; Save the Children; Sierra Leone Red Cross and International Federation of the Red Cross; UPHR-SL; World Hope International; Voice of Women; World Vision; and others.

5 The National SM Pillar contained four subcommittees: (a) Coordination, Monitoring, and Evaluation (UNICEF, MOHS coleads); (b) Messaging and Distribution (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, MOHS coleads); (c) Capacity Building (WHO, MOHS, coleads); and (d) Vulnerable groups (Handicap International, UNICEF). The Social Mobilization Action Consortium provided national- and district-level secretariat services.

6 People with visual or hearing impairment cannot access information in the same way as the general population. Different methods were needed to reach certain groups outside of the mainstream (e.g., commercial sex workers or people with disabilities). Different languages and low literacy levels also needed to be factored in to effectively reach different groups and communities.

7 SMAC includes partners BBC Media Action, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Focus 1000, GOAL, and Restless Development. Working within the strategy of the MOHS’s National SM Pillar, SMAC supported a network of 2,366 community mobilizers, 1,989 religious leaders, and 36 radio stations working across all districts in Sierra Leone (SMAC, 2015).

8 New confirmed cases decreased from a peak of 537 new cases in the week commencing November 24, 2014, to 184 new cases in the week commencing January 5, 2015 (WHO, Citation2015b).

9 In April 2015, two additional workshops were held in Koinadugu and Kono districts, where there were recent confirmed cases. These did not inform the development of the SOPs and are not included in this analysis.

10 These included district representatives from UNICEF, United Nations Mission for Ebola Emergency Response, U.K. Department for International Development,, WHO, the Institute of Medicine, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

11 Western Area does not have Paramount Chiefs; however, several ward councilors did attended. Unlike the other workshops, the Western Area workshop was only one day and did not include detailed action planning and mobilizer mapping. Ward-level action plans and ward-level mobilizer micromapping was instead done in smaller meetings over subsequent weeks.

12 For example, full training might include a full one-week pre-engagement training, including hands-on practice, as well as ongoing remedial/short-term trainings by experienced facilitators.

13 Between November 2014 and June 2015 more than 4,500 community alerts (sick and death) were made by SMAC community mobilizers through their community-based surveillance efforts, which included alerts called by SMAC-supported community champions, community mobilizers, and religious leaders.

14 The Community-Led Ebola Action (CLEA) methodology was developed by SMAC partners Restless Development and GOAL. It aims to empower communities to do their own analysis and take their own action to become Ebola free. CLEA triggers collective action by inspiring communities to understand the urgency and the steps they can take to protect themselves from Ebola (SMAC, Citation2014).

References

- Abramowitz, S. A., McLean, K. E., McKune, S. L., Bardosh, K. L., Fallah, M., Monger, J., … Omidian, P. A. (2015). Community-centered responses to Ebola in urban Liberia: The view from below. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 9(5), e0003767. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003706. pmid:25856076

- Benowitz, I., Ackelsberg, J., Balter, S. E., Baumgartner, J. C., Dentinger, C., Fine, A. D., & Layton, M. C. (2014). Surveillance and preparedness for Ebola virus disease—New York City, 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 63(41), 934–936.

- Dubois, M., & Wake, C. (2015, October). The Ebola response in West Africa: Exposing the politics and culture of international aid. Retrieved from the Overseas Development Institute website: http://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/9903.pdf

- Fast, S. M., Mekaru, S., Brownstein, J. S., Postlethwaite, T. A., & Markuzon, N. (2015, May 15). The role of social mobilization in controlling Ebola virus in Lofa County, Liberia. PLoS Currents, 7. doi:10.1371/currents.outbreaks.c3576278c66b22ab54a25e122fcdbec1

- Focus 1000. (2014). Study on public knowledge, attitudes, and practices relating to Ebola virus disease (EVD) prevention and medical care in Sierra Leone. KAP-1. Final report. Freetown, Sierra Leone: Author.

- Head, B. W. (2007). Community engagement: Participation on whose terms? Australian Journal of Political Science, 42(3), 441–454. doi:10.1080/10361140701513570

- Hewlett, B., & Hewlett, B. (2008). Ebola, culture and politics: The anthropology of an emerging disease. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

- Israel, B. A., Schulz, A. J., Parker, E. A., & Becker, A. B. (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19(1), 173–202. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173

- Jalloh, M. F., Sengeh, P., Monasch, R., Dyson, M., Jalloh, M. B., Deluca, N., … Bennelle, R. (2016). Baseline assessment of public knowledge, attitudes, and practices relating to Ebola Virus Disease during an Outbreak in Sierra Leone (SL Ebola KAP 1). Manuscript in preparation.

- Meltzer, M. I., Atkins, C. Y., Santibanez, S., Knust, B., Petersen, B. W., Ervin, E. D., … Washington, M. L. (2014, September 26). Estimating the future number of cases in the Ebola epidemic—Liberia and Sierra Leone, 2014–2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Supplements, 63 (03), 1–14.

- National Ebola Response Center. (2015). Weekly newsletter 2 November to 8 November 2015. Retrieved from http://nerc.sl/?q=national-ebola-response-centre-weekly-newsletter-2nd-november-8th-november-2015

- Republic of Sierra Leone. (2014). National communications strategy for Ebola response in Sierra Leone. Freetown, Sierra Leone: Author.

- Social Mobilization Action Consortium (SMAC). (2014). Community-led Ebola action field guide for community mobilizers. Retrieved from http://restlessdevelopment.org/file/smac-clea-field-manual-pdf

- Social Mobilization Action Consortium. (2015). Homepage. Retrieved from http://www.smacsl.org

- UNICEF. (2015). Communication for development (C4D). Retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/cbsc/index_65175.html

- World Health Organization. (2014a). Sierra Leone accelerated Ebola virus disease outbreak response plan. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/evd-outbreak-response-plan-west-africa-2014-annex4.pdf?ua=1

- World Health Organization. (2014b). Statement on the 1st meeting of the IHR emergency committee on the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2014/ebola-20140808/en/

- World Health Organization. (2015a). Ebola data and statistics. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.ebola-sitrep.ebola-country-SLE-20151125-data?lang=en

- World Health Organization. (2015b, January 28). Ebola situation report. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/ebola/en/ebola-situation-report/situation-reports/ebola-situation-report-28-january-2015

- World Health Organization. (2015c, February 4). Ebola situation report. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/151311/1/roadmapsitrep_4Feb15_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1