Abstract

During an emerging health crisis like the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, communicating with communities to learn from them and to provide timely information can be a challenge. Insight into community thinking, however, is crucial for developing appropriate communication content and strategies and for monitoring the progress of the emergency response. In November 2014, the Health Communication Capacity Collaborative partnered with GeoPoll to implement a Short Message Service (SMS)–based survey that could create a link with affected communities and help guide the communication response to Ebola. The ideation metatheory of communication and behavior change guided the design of the survey questionnaire, which produced critical insights into trusted sources of information, knowledge of transmission modes, and perceived risks—all factors relevant to the design of an effective communication response that further catalyzed ongoing community actions. The use of GeoPoll’s infrastructure for data collection proved a crucial source of almost-real-time data. It allowed for rapid data collection and processing under chaotic field conditions. Though not a replacement for standard survey methodologies, SMS surveys can provide quick answers within a larger research process to decide on immediate steps for communication strategies when the demand for speedy emergency response is high. They can also help frame additional research as the response evolves and overall monitor the pulse of the situation at any point in time.

In 2014, an Ebola outbreak in West Africa grew to become the worst ever witnessed (Frieden, Damon, Bell, Kenyon, & Nichol, Citation2014). Causing nearly 12,000 deaths—most of them in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone—it created widespread disruption and panic, even in countries that saw no cases. In Liberia, civil war and strife that had lasted for almost 14 years until its end in 2003 had left the nation’s health systems and infrastructure shattered (Downie, Citation2012; Iqbal, Citation2006). At the time of the outbreak of Ebola, everything from basic infrastructure to health systems and commodity supply was fragile and weak (Kieny, Evans, Schmets, & Kadandale, Citation2014; Kruk et al., Citation2010). These limited health systems significantly impeded a rapid and effective response to the emerging Ebola crisis (Kieny et al., Citation2014). As cases continued to rapidly emerge in the summer of 2014, poorly equipped health systems started to fall under the weight of the unprecedented and seemingly uncontrollable epidemic. Doubts about the ways in which Ebola was transmitted and how to prevent it, even at the international level, further created confusion, fear, and mistrust among those in the affected countries, who were pushed to the breaking point (World Health Organization [WHO] Ebola Response Team, Citation2014).

Almost 6 months after the initial outbreak, and as the scale of the epidemic was reaching its peak, the international community began to engage in a coordinated response to assist the three most affected countries in West Africa (Médecins Sans Frontières, Citation2014; Moon et al., Citation2015).

Intervening in such a chaotic state of emergency is difficult at best. Information from the front lines is hard to come by, let alone timely and accurate. But never is such information more needed to promptly develop communication strategies to effectively control an epidemic and at the same time address the strong emotions that accompany such a crisis. This poses significant challenges to health communication experts, researchers, and program implementers alike.

In Liberia, where the greatest number of deaths occurred, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) took advantage of an existing program mechanism, the Health Communication Capacity Collaborative (HC3), to mobilize resources, conduct data collection, and support research and interagency collaboration and coordination to curb the Ebola virus disease (EVD). This article describes one part of that effort, a mobile phone–based survey using Short Message Service (SMS) technology to rapidly collect information from communities on the front lines of the outbreak and feed that information back into the community response planning process, thus starting a dialogue with affected stakeholders. At the time, no data were available on the public’s level of knowledge about the Ebola virus, knowledge of its modes of transmission, or what kind of information communities needed to guide their response and help curb the epidemic.

Using Mobile Technologies

The ubiquity of mobile phone usage has been well documented. There are more than 5 billion mobile phone users globally, and it is estimated that approximately 85% of the world’s population live in areas with mobile network coverage; as of 2011, 70% of users lived in low- and middle-income countries (WHO, Citation2011). The use of mobile phones can transcend traditional barriers such as socioeconomic status and geographic location (Aker & Mbiti, Citation2010; Bornman, Citation2012; Kaplan, Citation2006; WHO, Citation2011) and has the potential to reach large numbers of people living in otherwise hard-to-reach locations, rapidly and repeatedly.

SMS technology has been used by health care providers to collect information from clients about health issues such as attempts at smoking cessation (Berkman, Dickenson, Falk, & Lieberman, Citation2011), to provide information or reminders to clients or stakeholders about such things as sexually transmitted disease prevention and testing (Kang, Skinner, & Usherwood, Citation2010; Wilkins & Mak, Citation2007; Ybarra & Bull, Citation2007), as well as for self-monitoring of drug adherence for people living with HIV (Swendeman et al., Citation2015) and other purposes (De Leon, Fuentes, & Cohen, Citation2014). However, little has been written specifically about the use of SMS as a potential survey data collection tool, and almost nothing has been written about this type of application in emergency contexts, such as the EVD outbreak. It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss other uses of SMS that occurred during the Ebola crisis, such as contact tracing (Tracey, Regan, Armstrong, Dowse, & Effler, Citation2015) and directing individuals to appropriate health centers (Trad, Jurdak, & Rana, Citation2015). We focus just on its use for formative research in the early stages of the outbreak.

Mobile data collection has been used successfully as a survey tool in various contexts in which a team of interviewers is trained to use a mobile device to conduct survey interviews (see for example www.pma2020.org). At the height of the Ebola crisis, it was neither feasible nor safe to send a team of interviewers to the field to gather nationally representative data. SMS offered the possibility of collecting such data without jeopardizing the safety of interviewers in a situation in which social gatherings and hand shaking were forbidden in order to prevent the rapid spread of the disease.

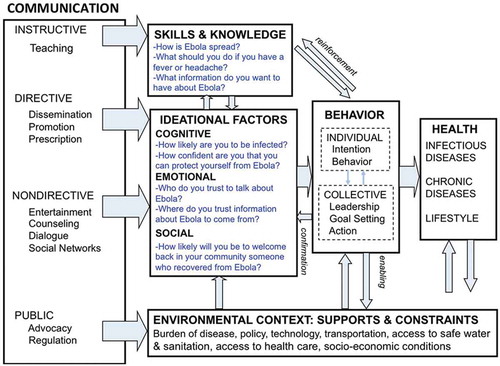

The very limited time available in emergency contexts calls for data that can provide rapid insights into the determinants of behavior. For such a purpose, widely validated theories of health communication and behavior provide an objective lens that can help to focus and guide thinking about study design without necessarily predisposing the study to certain conclusions. For the EVD response in Liberia, one such model used was the ideation metatheory of communication and behavior change (Kincaid, Delate, Storey, & Figueroa, Citation2012; see ). Originally developed to explain the decline in fertility in the developing world (Cleland & Wilson, Citation1987; Kincaid, Citation2000), the ideation metatheory has been widely used in and adapted to a variety of sociocultural settings and across a range of health and development issues, including family planning and reproductive health (Kincaid, Storey, Figueroa, & Underwood, Citation2006), HIV/AIDS prevention (Babalola, Citation2007), hygiene and water handling (Kincaid & Figueroa, Citation2010), and more recently malaria prevention (Ricotta et al., Citation2015), among others. The ideation metatheory (see ) describes a set of factors that separately and cumulatively influence behavior. These factors include skills and knowledge about the behavior, cognitive factors (e.g., attitudes about the health issue, perceived behavioral norms, perceived risk associated with the health threat, and self-efficacy to act), emotional factors (e.g., feelings of fear, trust, empathy, and compassion), and social influence factors (e.g., social support, interpersonal discussion, and peer pressure) as well as environmental factors that enable or prevent healthy behaviors. The specific factors that are relevant for a particular health issue vary depending on the context, but the application of this theory over time has shown that locally relevant ideational factors have a combined dose response effect on behavior (Kincaid et al., Citation2006).

Fig. 1. A metatheory of health communication: An adaptation for Ebola response in Liberia (adapted from Kincaid, Citation2000).

In the case of EVD in Liberia, this theory and available qualitative research that had been gathered by international organizations who were already in Liberia in the summer of 2014 guided the selection of the questions for the survey. Using this framework does not predetermine the specific ideation variables that will work in a particular situation, but it guides the thinking and the selection of variables that can be tested as predictors of the behavior of interest. By applying this theory to collect qualitative and quantitative data, research creates a theory-driven dialogue with the community (Kincaid et al., Citation2012) about how to respond in a contextually appropriate way to a particular health issue.

Using mobile technologies, such as SMS-based surveys, allows researchers to reach remote locations that are inaccessible through other means of data collection. It has the benefit of allowing immediate two-way communication and response to texted questions as well as direct data capture of the texted responses and easier data compilation and cleaning. It does, however, have some drawbacks associated with the limited length of messages that can be sent at one time and the limited number of questions that can be included in a survey delivered through this platform. Consequently, this limits the number of theoretical constructs that can be included in a survey. Nevertheless, the rapid deployment facilitated by SMS represents a valuable mechanism to open a line of communication with communities that are hard to reach by other means. Likewise, SMS-based surveys can pave the way for additional more in-depth qualitative and quantitative research and allow quick feedback in emergency scenarios when time is of the essence.

Study Methods

In November 2014, HC3 partnered with GeoPoll (a Mobile Accord company; www.research.GeoPoll.com) to design and roll out an SMS-based survey to conduct a rapid assessment of knowledge, efficacy, susceptibility, and severity as well as stigma surrounding Ebola. The SMS questionnaire was designed to produce a rapid assessment of ideational elements that could inform the content and strategy of the communication response.

GeoPoll has preexisting relationships with mobile network operators in countries around the world, which is key to rapidly rolling out surveys to specific population groups and geographic locations. A pool of previous survey respondents is used as a base population that can be supplemented by sending SMS messages to additional mobile subscribers in order to identify and recruit more respondents. At the time when Ebola was reaching its peak in Liberia, GeoPoll was finalizing its testing of its SMS survey system in the country. This allowed for immediate action, which would not have been possible if it had been necessary to build such a system from scratch .

SMS surveys do, however, impose some limitations on the content and length of the questionnaire. Questions and answers both have to be fewer than 160 characters, and open-ended questions need to be precoded. Based on past experience, GeoPoll recommended including a maximum of 12–15 questions in each survey, as response rates are found to drop off dramatically if the questionnaire is longer.

Respondents received the local equivalent of USD $0.50 in mobile credit on survey completion. Thirteen survey questions were crafted to provide a rapid assessment of these essential factors: knowledge of Ebola, perceived susceptibility to and severity of Ebola, self-efficacy to prevent infection, as well as stigma surrounding Ebola. Each of these questions had an analog in the ideational framework. Three additional questions investigated trusted sources of information and additional information needs among the Liberian population.

The SMS survey questions, 160 characters or fewer, are shown in exactly as they appeared on users’ mobile phones if they chose to participate. The table also shows the corresponding ideational categories for each item.

Table 1. Questions included in the Liberia SMS-based survey.

Survey Sampling

Finalized survey questions were submitted to GeoPoll on November 14, 2014. The following week, SMS questions were administered at a national level in Liberia with the goal of reaching 1,000 completed questionnaires. GeoPoll used a stratified sampling approach aligned with country demographic and geographic breakdowns in order to obtain a population-based representative sample. Within 3 days of the survey launch, 1,000 men and women older than the age of 15 years completed the SMS-based questionnaire. GeoPoll reported a 34% response rate, meaning that the company sent the questions to approximately 3,000 cell phone users in their database to obtain the expected 1,000 completed surveys. GeoPoll cleaned the data and provided the final data set for analysis on November 20, 2014—a period of only 6 days! The research team conducted some additional recoding of open-ended questions; some respondents had typed answers that were actually precoded in closed-ended questions or had typed multiple answers, perhaps not realizing that they could select multiple precoded options.

Results

Analysis of these data provided a snapshot of the current situation in all 15 counties of Liberia. Because of the timeliness of data collection—1,000 completed surveys within 3 days, and data cleaned and available for analysis within three additional days—the results were available almost immediately to inform the content of the communication response strategy.

Sample Distribution

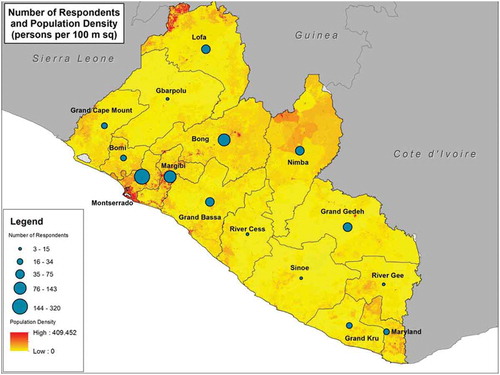

The sample distribution by geographic location (county level) was generally consistent with national statistics. However, with SMS surveys, the response rate tends to be skewed somewhat toward a younger male population. The median age of respondents was 26.8 years (range = 15–62). About 40% of respondents were 25–35 years of age, 16% were older than 35 years old, and about 45% were 15- to 24-year-olds. Nationally, the 15- to 24-year-old age group makes up 18% of the population, with 25- to 54-year-olds making up 31% of the population (Central Intelligence Agency, Citation2015). In addition, 46% of respondents were female and 54% were male. includes the descriptive statistics for each variable in the survey.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for survey questions (N = 1,000).

By geographic location, 32% of respondents were from Montserrado, the most populous county in which the capital, Monrovia, is located. A total of 17% of respondents were from less populous counties, including Bomi, Gbarpolu, Grand Gedeh, Grand Kru, River Cess, River Gee, and Sinoe. The combined population of these counties is approximately 591,367 inhabitants. About 51% of respondents were from more populous counties, such as Bong, Grand Bassa, Grand Cape Mount, Lofa, Margibi, Maryland, and Nimba, which together contain approximately 1,767,000 inhabitants.

presents a map displaying 2014 population density estimates (persons per 100 square meters) overlaid with graphics representing the number of respondents by county. The distribution of respondents was proportional to the overall geographic distribution of the population across counties.

The following is a summary of results highlighting key findings about the ideational variables included in the survey. Because respondents were able to select more than one answer for many questions, the totals sometimes add up to more than 100% (see ).

Trusted Sources of Information

When asked about trusted sources of Ebola-related information, only 9% of respondents identified the government, whereas 82% identified health care workers. About 1 in 10 respondents identified religious leaders, followed by teachers (8%) and traditional leaders (6%), as sources of Ebola-related information.

Preferred Sources of Information

When asked about their preferred source of Ebola-related information, participants ranked health centers highest (63%), followed by community meetings (53%); 30% also wanted information from the radio.

Knowledge of How Ebola Spreads

In response to the question about how Ebola is spread, 45% identified body fluids and a similar percentage selected touching dead bodies as sources of infection as well as shaking hands; 96% knew that Ebola was not spread by air. A knowledge score (from 0 to 6) was calculated based on the number of correct responses for modes of transmission (M = 2.17, SD = 2.001). A total of 96% of respondents correctly identified at least one correct mode of transmission, but only 15% of respondents knew all six modes of Ebola transmission (bush meat, blood/vomit/diarrhea, semen, saliva, shaking hands, touching dead bodies).

Knowledge of Ebola transmission was significantly correlated with age. The percentage of respondents who knew all six correct modes of transmission (of those provided as precoded answers) increased with age, from 11% among those 15 to 24 years old to 17% for those 25 to 35 years old to 21% for those 35 years or older (p < .01; see ). This positive correlation with age remained after we controlled for gender. However, there was not a significant association between knowledge and gender.

Table 3. Knowledge of modes of transmission by age group.

Perceived Susceptibility and Self-Efficacy

Half of all respondents felt that they were not at all likely to become infected, and about 30% indicated that they were very likely to get infected. Moreover, 79% of respondents were very confident that they could protect themselves, and about 8% indicated not being confident at all. Likelihood of getting infected was negatively associated with confidence in protecting oneself from Ebola. Of those who were very confident, 53% felt not at all likely to become infected, whereas of those who felt otherwise, 41% felt not at all likely to become infected (see ).

Table 4. The relationship between perceived risk and self-efficacy.

Care Seeking

Seeking appropriate health care was a key behavior that needed to be quickly investigated given the negative rumors circulating about the Ebola Treatment Units (ETUs) at the time. The results showed that 84% of respondents reported that they would go to a clinic immediately if they had a fever or headache, and 20% reported that they would call for help.

Ebola Recovery

Approximately 90% believed that someone could recover from Ebola, with 64% reporting that they knew someone who had recovered from the disease.

Stigma

A total of 74% of respondents reported that they were very likely to welcome back a survivor into the community.

Desired Ebola-Related Information

Almost half of respondents wanted more information about Ebola prevention, and about 20% wanted information about the original cause of the outbreak as well as about signs and symptoms. Approximately 30% of respondents desired information about treatment and what happens at ETUs.

Discussion

The results of the SMS-based survey provided important insights into key determinants of behavior regarding EVD. Results verified the need for community-based solutions, suggested key themes necessary to include during message content development, and reinforced some aspects of ad hoc communication strategies that were already in place.

The results showed that although knowledge was high, people desired additional information about how to prevent infection. The finding showing that respondents wished to know what happened at ETUs was a key piece of information, as rumors were spreading rapidly about ETUs being unknown places where people went to die or simply to disappear. Nevertheless, the majority of respondents identified health workers as trusted to talk about EVD, perhaps because, as members of the community, health workers are more familiar. These findings underscore the importance of continuing to build trust and enhance communication between communities and health providers, who tend to be the first responders. The limited space in the survey prevented further exploration of other options included in the survey, such as the government or traditional leaders. The government was instrumental in the response and control of the EVD outbreak, which the limited GeoPoll survey could not ascertain. Likewise, traditional leader may not have been the optimal term to represent community leaders, who were mentioned as significant resources by participants in a qualitative study that was conducted later in the year (HC3, 2015; Nyenswah et al., Citation2016; WHO, Citation2015a).

Despite the relatively limited reach of radio, almost one third of respondents wished to receive messages from radio, which suggests the value of the media in legitimizing issues and setting the agenda. Qualitative data revealed such value of the radio: Participants in a qualitative study conducted in December 2014 referred to radio as a credible and desired source of health information (HC3, 2015).

In exploring the relationship between self-efficacy (confidence in being able to protect oneself from infection) and perceived susceptibility (likelihood of being infected), we found that those with higher self-efficacy in protecting themselves felt less susceptible to infection, whereas those with little or no confidence felt more susceptible to infection.

The extended parallel process model (EPPM) posits that with increased threat perception (which includes susceptibility) there is greater motivation to practice preventive health behaviors, so long as perceived efficacy (which includes self-efficacy) is also high (Witte, Citation1992). In our study, 37% of all respondents both were very confident and felt somewhat or very susceptible. According to the EPPM, it is these individuals who would be most motivated to act and for whom health messaging would be most persuasive. A total of 42% of all respondents felt very confident but not at all likely to become infected. If these individuals were underestimating threat, this has implications for messaging content. A typical EPPM-based strategy in such a case would be to educate low-fear individuals about transmission vectors and about the risks they realistically face in order to increase motivation to act on their behavioral confidence.

There was not space in the GeoPoll survey to explore further other elements of the EPPM, such as perceived threat severity or response efficacy, nor was there space to ask about preventive health behaviors. Further research could have probed these issues to see what preventive actions respondents were taking and whether those behaviors were related to higher threat and efficacy perceptions.

The relatively high percentages of people who said that it is possible to recover from Ebola and who said that they knew someone who had recovered seem high given how frightening and alarmist the news of Ebola fatalities was at the time. But in retrospect, WHO (Citation2015b) estimated the case fatality rate in Liberia at 45.1%, so these figures may reflect the reality on the ground. It is not completely clear, however, whether people were answering the question about knowing survivors based on personal knowledge of someone who had survived or based on knowledge of a survivor.

With regard to stigma, the findings did not indicate that it would contribute much to harmful discrimination, but the space limitations in the GeoPoll survey did not allow further exploration of this topic. Anecdotal evidence from other sources indicated significant levels of concern about whether survivors were still infectious. Additional research was needed to get a better sense of the reactions of the communities to survivors of such a deadly disease. Some subsequent qualitative research and population-based surveys conducted by others further investigated these issues, including a study on community perspectives about Ebola (HC3, 2015) and the national Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices survey mentioned below.

Results of the GeoPoll survey were presented to the Research, Monitoring, and Evaluation group under the Social Mobilization Pillar of the Incident Management System of the Liberia Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. The Incident Management System was the Liberian government’s primary system through which efforts were coordinated for dealing with the EVD outbreak on the front lines. In addition to being used to refine the communication response, the data were also used by at least two other organizations working in the country at that time to inform their own data collection activities. The Liberia Ministry of Health and Social Welfare and UNICEF also used the results to inform their own national Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices survey, which they launched in December 2014.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

Overall, the SMS-based experience in Liberia for the EVD response proved to be valuable, but it also presented various challenges and limitations. One such limitation was that respondents had to be literate and have access to a mobile phone. Mobile phone ownership and usage may have been skewed toward younger individuals, those who had more access to resources, and males. Thus, we must acknowledge that the results will not be as representative of the population as those of surveys that use probability-based sample designs.

In addition, SMS messages are limited to 160 characters, which constrained the space available for the questions to be asked. In fact, crafting the question properly may be the biggest challenge in conducting such a survey. A question, along with answer options, must all be contained in (ideally) one SMS message. Questions must be designed to be as clear and concise as possible, all while minimizing the chance of misunderstanding by the respondent. It should be noted that because of the 160-character limit and the desire to keep the survey brief, we were unable to probe further into, for example, stigma, which was measured by asking respondents whether they would welcome survivors back into their communities. The response to this question was more than 70%, which seems high given the prevailing conditions at the time. Responses to open-ended questions must also contain fewer than 160 characters and furthermore must be postcoded by researchers for analysis. This may require training and reliability checks, which we did not conduct in this study because of time constraints.

Conclusion

At the peak of the Ebola outbreak, communication researchers and practitioners had limited time and resources to understand determinants of behavior and develop an effective communication strategy to help curb EVD. Confronted with such an urgent need at the peak of the worst EVD epidemic ever, responding agencies were often unclear where to start in such an overwhelming situation. Strategically relevant research questions needed to be identified and answered in order to inform an effective communication response. Using widely validated theories like ideation as the basis for questions asked using an existing SMS platform allowed researchers to take the pulse of the situation and of the communities being affected. Deployed at the peak of the epidemic, the GeoPoll survey provided a crucial snapshot of the situation on the ground in almost real time from remote regions hardly accessible by other means under such conditions. To our knowledge, the SMS-based survey was the first survey to provide data at the national level in Liberia on key factors of behavior related to EVD.

SMS-based surveys are not intended to be a substitute for standard probability-based population surveys. Rather, they should be considered one solution for obtaining rapid, concise data for programmatic decision making when other options are unavailable and are best viewed as part of a larger research process. SMS communication is a methodology that can be implemented expeditiously, particularly at an early formative stage of planning, and that can have both immediate value for an early-phase response as well as subsequent value for the development of further research questions in the evolution of program strategies. If the SMS survey is theory based, as this one was, it can be more than descriptive. It can be used to explore ideational and behavioral factors and support initial exploratory behavioral modeling for strategy development.

Furthermore, although this study was used primarily for formative research purposes, SMS-based surveys lend themselves well to program monitoring. They can be designed and implemented quickly to generate timely, even periodic, data for ongoing, nearly real-time monitoring of program activities, outputs, and outcomes, which is critical throughout a program implementation cycle (Chen, Citation2005). Ongoing monitoring throughout the implementation process plays a key role in tracking changes over time, provides feedback for course corrections, can identify when and how changes occur, and increases the likelihood of program impact.

The use of mobile technologies is not simply warranted—it is needed. Theory-based mobile data collection holds tremendous promise for the future of program design and monitoring: It provides a way to initiate dialogue with communities and maintain engagement with the public over time. Mobile data collection is now being used in Liberia and other Ebola-affected countries for monitoring during the recovery phase program activities to provide timely feedback, and it could become a valuable resource for future health interventions in other countries and for other health issues.

References

- Aker, J., & Mbiti, I. (2010). Mobile phones and economic development in Africa. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24(3), 207–232. doi:10.1257/jep.24.3.207

- Babalola, S. (2007). Readiness for HIV testing among young people in northern Nigeria: The roles of social norm and perceived stigma. AIDS and Behavior, 11, 759–769. doi:10.1007/s10461-006-9189-0

- Berkman, E., Dickenson, J., Falk, E., & Lieberman, M. (2011). Using SMS text messaging to assess moderators of smoking reduction: Validating a new tool for ecological measurement of health behaviors. Health Psychology, 30(2), 186–194. doi:10.1037/a0022201

- Bornman, E. (2012, May). The mobile phone in Africa: Has it become a highway to the information society or not? Paper presented at the International Conference on Communication, Media, Technology and Design, Istanbul, Turkey.

- Central Intelligence Agency. (2015). Liberia world factbook. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/li.html

- Chen, H. (2005). Practical program evaluation: Assessing and improving planning, implementation, and effectiveness. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Cleland, J., & Wilson, C. (1987). Demand theories of the fertility transition: An iconoclastic view. Population Studies, 41(1), 5–30. doi:10.1080/0032472031000142516

- De Leon, E., Fuentes, L., & Cohen, J. (2014). Characterizing periodic messaging interventions across health behaviors and media: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(3), e93. doi:10.2196/jmir.2837

- Downie, R. (2012). The road to recovery: Rebuilding Liberia’s health system. Retrieved from http://csis.org/files/publication/120822_Downie_RoadtoRecovery_web.pdf

- Frieden, T., Damon, I., Bell, B., Kenyon, T., & Nichol, S. (2014). Ebola 2014—New challenges, new global response and responsibility. New England Journal of Medicine, 371(13), 1177–1180. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1409903

- Health Communication Capacity Collaborative. (2015). Community perspectives about Ebola in Bong, Lofa and Montserrado Counties of Liberia: Results of a qualitative study. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, Health Communication Capacity Collaborative, Resource Center for Community Empowerment and Integrated Development.

- Iqbal, Z. (2006). Health and human security: The public health impact of violent conflict. International Studies Quarterly, 50, 631–649. doi:10.1111/isqu.2006.50.issue-3

- Kang, M., Skinner, R., & Usherwood, T. (2010). Interventions for young people in Australia to reduce HIV and sexually transmissible infections: A systematic review. Sexual Health, 7(2), 107–128. doi:10.1071/sh09079

- Kaplan, W. A. (2006). Can the ubiquitous power of mobile phones be used to improve health outcomes in developing countries? Globalization and Health, 2, 9. doi:10.1186/1744-8603-2-9

- Kieny, M. P., Evans, D. B., Schmets, G., & Kadandale, S. (2014). Health-system resilience: Reflections on the Ebola crisis in western Africa. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 92(12), 850. doi:10.2471/BLT.14.149278

- Kincaid, D. (2000). Mass media, ideation, and behavior: A longitudinal analysis of contraceptive change in the Philippines. Communication Research, 27(6), 723–763. doi:10.1177/009365000027006003

- Kincaid, D., Delate, R., Storey, J., & Figueroa, M. (2012). Advances in theory driven design and evaluation of health communication campaigns: Closing the gap in practice and theory. In R. Rice & C. Atkin (Eds.), Public communication campaigns (4th ed., pp. 305–320). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Kincaid, D., & Figueroa, M. (2010). Social, cultural and behavioral correlates of household water treatment and storage (Center Publication No. HCI 2010-1: Health Communication Insights). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Center for Communication Programs.

- Kincaid, D., Storey, J., Figueroa, M., & Underwood, C. (2006, October). Communication, ideation, and contraceptive use: The relationships observed in five countries. Paper presented at the World Congress on Communication for Development, Rome, Italy.

- Kruk, M. E., Rockers, P. C., Williams, E. H., Varpilah, S. T., Macauley, R., Saydee, G., & Galea, S. (2010). Availability of essential health services in post-conflict Liberia. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 88(7), 527–534. doi:10.2471/BLT.09.071068

- Médecins Sans Frontières. (2014, December 2). Ebola: International response slow and uneven. Retrieved from http://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/article/ebola-international-response-slow-and-uneven

- Moon, S., Sridhar, D., Pate, M., Jha, A., Clinton, C., Delaunay, S., … Piot, P. (2015). Will Ebola change the game? Ten essential reforms before the next pandemic. The report of the Harvard-LSHTM Independent Panel on the Global Response to Ebola. The Lancet, 386, 2204–2221. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00946-0

- Nyenswah, T., Kateh, F., Bawo, L., Massaquoi, M., Gbanyan, M., Fallah, M., … Sieh, S. (2016). Ebola and its control in Liberia, 2014–2015. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 22(2), 169–177. doi:10.3201/eid2202.151456

- Ricotta, E. E., Boulay, M., Ainslie, R., Babalola, S., Fotheringham, M., Koenker, H., & Lynch, M. (2015). The use of mediation analysis to assess the effects of a behaviour change communication strategy on bed net ideation and household universal coverage in Tanzania. Malaria Journal, 14, 15. doi:10.1186/s12936-014-0531-0

- Swendeman, D., Ramanathan, N., Baetscher, L., Medich, M., Scheffler, A., Comulada, W., & Estrin, D. (2015). Smartphone self-monitoring to support self-management among people living with HIV: Perceived benefits and theory of change from a mixed-methods randomized pilot study. JAIDS: Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 69, S80–S91. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000000570

- Tracey, L., Regan, A., Armstrong, P., Dowse, G., & Effler, P. (2015). EbolaTracks: An automated SMS system for monitoring persons potentially exposed to Ebola virus disease. Eurosurveillance, 20(1), 1–4. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES2015.20.1.20999

- Trad, M. A., Jurdak, R., & Rana, R. (2015). Guiding Ebola patients to suitable health facilities: An SMS-based approach. F1000Research, 4, 43. doi:10.12688/f1000research.6105.1

- Wilkins, A., & Mak, D. (2007). Sending out an SMS: An impact and outcome evaluation of the Western Australian Department of Health’s 2005 chlamydia campaign. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 18(2), 113–120.

- Witte, K. (1992). Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Communication Monographs, 59(4), 329–349. doi:10.1080/03637759209376276

- World Health Organization. (2011). mHealth: New horizons for health through mobile technologies (Global Observatory for eHealth series—Vol. 3). Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44607/1/9789241564250_eng.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2015a). Liberia succeeds in fighting Ebola with local, sector response. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/features/2015/ebola-sector-approach/en/

- World Health Organization. (2015b). Statistics on the 2014-2015 West Africa Ebola outbreak. Retrieved from http://www.johnstonsarchive.net/policy/westafrica-ebola.html

- World Health Organization Ebola Response Team. (2014). Ebola virus disease in West Africa—The first 9 months of the epidemic and forward projections. New England Journal of Medicine, 371(16), 1481–1495. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1411100

- Ybarra, M., & Bull, S. (2007). Current trends in Internet- and cell phone-based HIV prevention and intervention programs. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 4(4), 201–207. doi:10.1007/s11904-007-0029-2