Abstract

A national integrated polio, measles, and deworming campaign was implemented across Liberia May 8–14, 2015. The community engagement and social mobilization component of the campaign was based on structures that had been invested in during the Ebola response. This article provides an overview of the community engagement and social mobilization activities that were conducted and reports the key findings of a rapid qualitative assessment conducted immediately after the campaign that focused on community perceptions of routine immunization in the post-Ebola context. Focus group discussions and interviews were conducted across four counties in Liberia (Montserrado, Nimba, Bong, and Margibi). Thematic analysis identified the barriers preventing and drivers leading to the utilization of routine immunization. Community members also made recommendations and forwarded community-based solutions to encourage engagement with future health interventions, including uptake in vaccination campaigns. These should be incorporated in the development and implementation of future interventions and programs.

The first confirmed case of Ebola virus disease in Liberia was in March 2014. During the outbreak, which peaked in September 2014, there were 10,675 confirmed, probable, and suspected cases (including 378 cases among health workers) and 4,809 confirmed deaths (including 192 health workers).Footnote1 The World Health Organization declared Liberia Ebola free on May 9, 2015, and then again on September 3, 2015 (42 days after the second negative test of the laboratory-confirmed case on July 22, 2015); however, in November 2015 three new confirmed cases of Ebola virus disease were reported, and at the time of writing, the response to stop further transmission was ongoing.

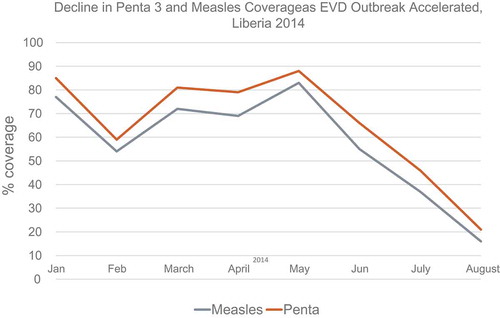

In Liberia, as in the other most affected countries in West Africa, the Ebola epidemic led to a disruption in essential health services and resulted in low coverage of routine immunization (see ).

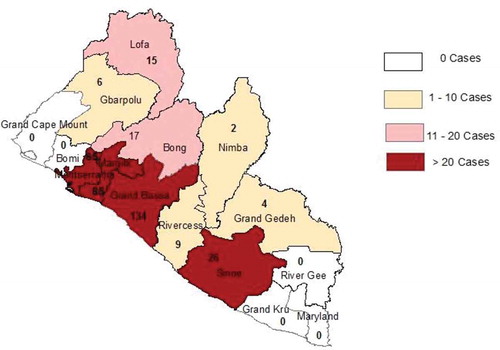

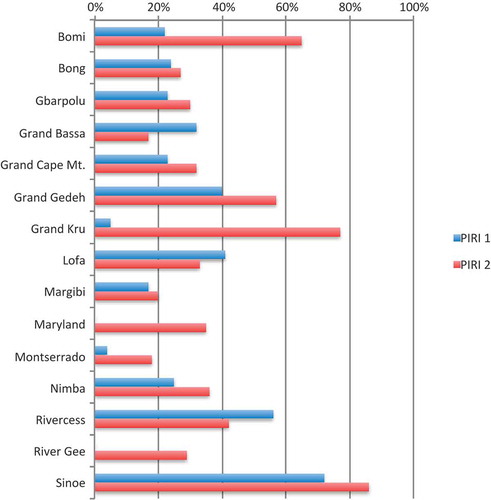

Measles is one of the leading causes of death among children younger than 5 years of age, and compared to other vaccine-preventable diseases is particularly contagious and associated with significant mortality. Two Periodic Intensification of Routine Immunizations (PIRI) campaigns failed to raise coverage to the pre-Ebola level of 89% (in 2013). The first PIRI in December 2014 had an average coverage rate of 20%, and the second in February 2015 achieved 30%, leaving many children at risk (see ). By May 2015, 562 measles cases had been reported in 10 of Liberia’s 15 counties (Bong, Gbarpolu, Grand Bassa, Grand Gedeh, Lofa, Margibi, Montserrado, Nimba, Rivercess, and Sinoe), and seven deaths had been confirmed (see ).

Fig. 2. Comparative coverage of Periodic Intensification of Routine Immunizations (PIRI) Rounds 1 and 2.

In response to the low levels of coverage in PIRI Rounds 1 and 2 and ongoing challenges in reintroducing services during the post-Ebola recovery phase, the Ministry of Health, with support from UNICEF and other partners, conducted a national Integrated Polio, Measles, and Deworming campaign May 8–14, 2015. The campaign targeted all children younger than 5 years old and provided vaccination services at static sites (health clinics and hospitals) and mobile temporary sites (for community outreach). The goal of the campaign was to ensure that every child between 0 and 59 months received the oral polio vaccine, every child between 6 and 59 months received the measles vaccine, and every child between 12 and 59 months received a mebendazole tablet.

For the campaign to be a success and achieve sufficiently high levels of coverage, it was clear that substantial preparation and engagement was needed at the community level. Although established protocols and operational modalities existed for the planning and implementation of similar campaigns, the main challenge was to rebuild confidence in the health system post-Ebola and to address concerns and fears about routine immunization and the Ebola vaccine.

Social Mobilization Efforts

Underutilization of routine immunization has always been present in Liberia. According to the 2012 Routine Immunization Coverage Survey, 22% of mothers reported that they were too busy to go to vaccine services, 11% said that they did not know about the need to return for multiple doses of vaccine, and 7% claimed that they did not know about the need for immunization. The Ebola epidemic exacerbated this situation and resistance to immunization due to fear, and misinformation had the potential to negatively impact the campaign and significantly increase the number of children at risk of contracting preventable diseases. Intensive interpersonal communication at community and household levels was seen as a priority in order to build the level of understanding and acceptance of routine immunization, address fears and misinformation, and reestablish trust in the routine immunization program.

A comprehensive social mobilization and community engagement plan was developed by the Ministry of Health based on the social mobilization strategy used during the Ebola response and drawing on lessons learned from previous immunization campaigns. The aim of the communication strategy was two-fold: first, to increase communities’ understanding of the importance of routine immunization; and second, to raise awareness of the campaign by strengthening interpersonal communication about routine immunization and the campaign through community engagement of social networks and house-to-house mobilization, conducting high-level advocacy in the counties, using partners to raise the profile of measles and polio immunizations, and providing support in developing specific communication plans for communities.

In collaboration with the Ministry of Health and its Health Promotion Unit, UNICEF provided technical leadership in rolling out the social mobilization activities and through County Mobilization Coordinators (CMCs) and District Mobilization Coordinators (DMCs) coordinated the social mobilization activities of partners at county and district levels. Between the end of March and the start of the campaign in May, there were a number of integrated streams of activity, including training of trainers; mobilization of chiefs and town criers; orientation of civil society organizations, religious leaders, and the traditional women’s network; mass communication (through radio, printed press, posters and flyers, and parades); direct engagement activities, including door-to-door visits and community-based dialogues; and rapid polls through U-report, a free Short Message Service (SMS)–based platform used to promote the campaign and seek feedback during and following its rollout.

Overall, UNICEF concluded that 229,031 house-to-house visits were conducted; 5,992 community leaders and 5,840 religious and traditional leaders were engaged and trained; 2,760 community meetings were held; 35,000 flyers, 5,678 posters, and 60 banners were printed and distributed; and three radio dramas were produced and aired over 67 radio stations.

Routine Immunization Campaign Outcome

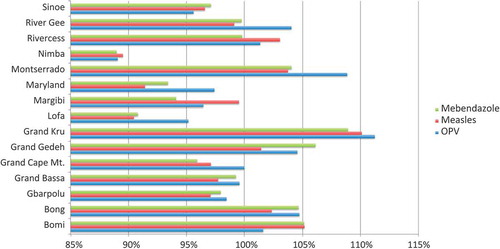

There was good coverage across the campaign. In total, 693,622 children (101%) received the oral polio vaccine, 596,545 (99%) received the measles vaccine, and 518,104 (99%) received the mebendazole tablet (see and ).

Fig. 4. Oral polio vaccine (OPV), measles, and mebendazole by target, total, and coverage percentage per county.

This represented a substantial increase in the number of children vaccinated (compared with the two earlier PIRIs) and was in part due to good collaboration and cooperation between the Community Health Teams, UNICEF, and other partners. The social mobilization activities were well coordinated and had a positive impact, particularly with previously resistant communities who were targeted for direct engagement and sensitization during the immunization campaign.

UNICEF conducted exit interviews with caregivers presenting their child(ren) for immunization across all 15 counties (n = 737). In response to the question “In the past few weeks, did you receive or hear any messages to get children under five to get immunized?” 94.3% of respondents (n = 695) affirmed that they had. In response to the question “How did you hear this/these message/s?” the most often cited sources of the information were (in decreasing order) Community Health Volunteer (CHV) or other health worker (72.8%, n = 516); health worker visited our house (56.7%, n = 402); poster, billboard, or flyer (55%, n = 390); radio (49.5%, n = 351); community meeting or community leader (46.5%, n = 33); town crier (44%, n = 312); and friends, neighbors, relatives (42.6%, n = 302).

Methods

Rapid Qualitative Assessment

Following the immunization campaign, a rapid qualitative assessment was conducted in four counties (Montserrado, Nimba, Bong, and Margibi). The aim of the assessment was three-fold: to determine the barriers to and drivers for routine immunization; to determine the barriers to and drivers of routine immunization uptake during the campaign; and to identify and document examples of positive community engagement during and after the Ebola outbreak in terms of community self-mobilization, leadership, and innovation.

Data Collection

Data collection was conducted in four counties over 8 days: Montserrado (May 15–16), Nimba (May 18–19), Bong (May 20–21), and Margibi (May 22–23). The rapid assessment was conducted in line with prevailing ethical principles to protect the rights and welfare of all participants. Permission to undertake the research was granted by the County Health Teams and was supported by the UNICEF Country Office.

In each county, three communities were visited. The communities were selected by the local CMCs and DMCs and included one community in which immunization uptake had been positive and coverage was high, one community in which there had been resistance to immunization and coverage was lower, and one community that had demonstrated innovation and self-leadership during the Ebola outbreak.

At each site, a focus group discussion was conducted with community members, primarily caregivers (mothers, fathers, and grandmothers) and community leaders. The discussion was structured by a topic guide, but the direction and content of each focus group was determined by the participants and focused on issues they prioritized, although all components of the framework were covered to ensure thematic comparison across communities. All focus group discussions were conducted by the primary investigator (JB), supported by a CMC and/or DMC, who translated between English, Liberian English, and local languages as necessary. A number of focus groups were observed by County Health Team representative(s). All participants gave their consent by signing or putting their thumbprint on a standard UNICEF consent form and were provided with refreshments (a soft drink and biscuits) after the discussion. The consent forms were deposited with the UNICEF Liberia country office at the conclusion of the study.

At one site in Monrovia (20th Street), mothers who had not taken their children for immunization were interviewed individually rather than in a group discussion. In Nimba county, communities that had good vaccine uptake and poor vaccine uptake were visited, but because the former also demonstrated positive leadership during the Ebola outbreak, the research team used the additional time to visit a community clinic to engage with health staff who had been providing immunization services during the campaign. An additional interview was conducted with the doctor and officer-in-charge (OIC) of the Bahn Health Centre that serves the Bahn Refugee Camp in Nimba (hosting refugees from Côte D’Ivoire). The communities visited and the number of activities and participants is presented in .

Table 1. Activities and participants per community visited in the study

In addition, CMCs, DMCs, and general Community Health Volunteers (gCHVs) who facilitated the study in each county were also interviewed about their work (see ). Therefore, the total number of participants in the study was 141. During the campaign, observations were also made in two communities in Monrovia (Soniwein and 20th Street, Sinkor). The first set of observations focused on interactions between health workers and mothers presenting their children for immunization. The second set of observations focused on interactions between mobilizers (CMCs, DMCs, and gCHVs) and community members.

Table 2. Additional interviews per county

Data Analysis

The focus group discussions and interviews were not recorded; however, the primary investigator took detailed notes during each data collection session, and these were fully transcribed and annotated with comments and analysis. At the end of data collection in each county, the notes were reviewed with the CMCs and key points were verified. Preliminary analysis was conducted throughout the data collection process and initial findings were presented to UNICEF and to representatives from the Community Health Teams in Nimba and Margibi.

Thematic analysis developed specifically for analyzing data generated through applied qualitative research was used. Dominant themes were identified through the systematic review of focus group discussions, interviews, and observations. This involved systematically sorting through the data, labelling ideas and phenomena as they appeared and reappeared. The trends that emerged were critically analyzed.

Methodological Limitations

The rapid assessment was undertaken within a limited timeframe; however, the impact of this was limited by using a pragmatic methodology aimed at utilizing resources efficiently in the targeted counties. Risks associated with miscommunication or mistranslation were mitigated by the CMCs being present at each focus group discussion and reviewing the transcripts made by the primary investigator. Sections of narrative were read back to participants for their clarification and confirmation.

It is possible that participants expressed answers that they perceived to be appropriate or socially desirable responses, although the candor with which the majority of participants discussed their fears and frustrations suggested that such bias was unlikely. Observational data compiled during the study (e.g., the existence of hand-washing stations at the household or community level) also served as a method of verification. In addition, the focus group frameworks allowed similar questions to be asked in multiple ways in order to triangulate responses across relevant stakeholders.

This study is specific to certain communities in Liberia. Given the sample size of the study, results cannot be extrapolated to a wider country context, although the saturation of findings indicate that the data are likely to be broadly representative.

Results

Results were clustered into three key themes: barriers to immunization uptake, drivers of immunization uptake, and community recommendations for future interventions (see ). No participant reported not knowing about the measles and polio campaign, confirming a high level of awareness due to social mobilization activities, direct and indirect communication, and wide publicity.

Table 3. Key themes

Discussion

Barriers to Immunization Uptake

Barriers to immunization uptake were identified by all groups of stakeholders who participated in the focus group discussions, including mothers and caregivers who had not presented their children, currently or previously resistant communities, and communities in which utilization was good.

For many of the caregivers who did not present their child, this was a decisive choice. Some community members remained concerned about attending the recently re-opened health facilities. One mother in Monrovia explained, “I saw people going [to the clinic during the campaign], but I didn’t really pay attention, I didn’t want to take notice because even though Ebola has ended, I am still afraid.” This was particularly concerning as the mother was heavily pregnant, and she was uncertain as to whether she would deliver at the health facility, hinting that she may deliver in the “safety” of her home.

The ongoing concern regarding facility attendance and the lack of trust in health services in a post-Ebola context was echoed by a number of participants, but it was a view tempered by others who concluded, “Some people are still scared. Even though the hospital is open now, some people still don’t go, but then some people don’t go anyway, and they are normally frightened of the injection or swallowing tablets.” One community leader in Bong emphasized that there was a historical precedent of avoiding “external” biomedical health care:

If I saw you [a health professional] coming, I would bar my door and run. When I was small, my auntie would put me in the attic to hide me from you until you had gone, so I never had the measles vaccine.

This view was also discussed by CMCs and DMCs in Monrovia, who explained, “Even before Ebola, not all children were vaccinated. The denial didn’t start today or yesterday, it has been existing for long.”

The ongoing fear created by Ebola also extended to communities’ suspicion of health workers. One caregiver in Margibi who had not taken her children for immunization confirmed, “I didn’t believe what the health workers told us. We heard many things in Ebola time, and I trust the health workers less because they might just try to destroy people.” In several hard-to-reach areas, temporary mobile immunization sites were set up at the community level during the campaign, and this heightened distrust.Footnote2 A participant in one community focus group in Bong confirmed, “Before we would go to the clinic for immunization, but this time it was here in the community, so we started to think it was a problem for us.” Another mother in Bong concluded, “Before we would walk to the hospital at 5 a.m., but this time the vaccine came to our doors, so we were scared.” A mother in Margibi echoed this view, concluding:

That they came to the village with the vaccine made me afraid more because they bought it here now. We don’t know why. And we were told that a strange person should not go to the house. But actually it is better they bring it here, it is easier for us than going to the hospital where we have to take the step [e.g., walk to the hospital] but even so, it gave me cause for concern.

In response to this observation, the CMCs in Margibi explained that although the campaign strategy was not to go door to door, they encouraged some members of the vaccination team to do household-level outreach in an attempt to encourage caregivers to present their children when turnout was perceived to be too low.

A small number of participants recounted how immunization teams (during the PIRIs) had worn personal protective equipment (PPE) and that this caused communities to be afraid. A woman leader in Margibi explained:

At that time, in February, they had on PPE and only two mothers went, all the others ran away because during Ebola time when people came for the bodies, they were dressed like that, so we were afraid. This time when they came for immunization there was no PPE because Ebola had finished.

Similarly, a resistant community in Nimba county suggested:

Before Ebola we took the measles vaccine, but the reason we didn’t take it now was because of Ebola. When the people came to give the vaccine, they were bringing those Ebola things, like chlorine and buckets and temperature scanners, those things from Ebola time. So we were asking, if it is really measles, why are you bringing these things? There was even a crowd control rope like in Ebola time [similar to a quarantine rope].

In contrast, a CMC in Nimba recounted how during the May campaign:

We saw one team wearing PPE near the Ivory [Côte D’Ivoire] border. We had been told that people should not wear it, but the OIC told us that they had met with the town chief and explained it was for their protection and the town chief explained it to the community. The turn out was good, so for that community that attired worked. It was the team from the hospital who decided for themselves, just to wear light PPE. Before we went, a team from [the World Health Organization] had been there and they also asked the same thing.

Although there was no apparent detrimental effect on uptake as a consequence of the health team wearing PPE in this community, it was telling that despite Ebola being declared over prior to the campaign, health professionals continued to feel sufficiently at risk that they determined to wear PPE in contrast to the official no-PPE policy.

No participant in the assessment reported religious convictions preventing them from accepting immunizations, yet CMCs and DMCs in Monrovia emphasized that one of the most resistant communities they had encountered were the Fula because of their religious beliefs and traditional structures.

Rather, across the four counties included in the study, the strongest barriers to immunization uptake resulted from (a) the fear and suspicion communities continued to experience in relation to Ebola (“They said that the vaccine was for the children, but it was not easy for us because we were thinking of the past, of that Ebola era. Ebola made people scared, we were never afraid of the measles vaccine before”) and (b) negative perceptions resulting from the Ebola vaccine trial.

Between February and May 2015, the Partnership for Research on Ebola Vaccines in Liberia (PREVAIL), a Liberia–U.S. clinical research partnership sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, ran an Ebola vaccine trial in Montserrado county restricted to people older than 18 years of age. At the time of the research, the popular perception of the Ebola vaccine was inherently negative and detrimental to communities’ trust in the immunization campaign, as many people confused or conflated the measles and polio vaccines with the Ebola vaccine. Despite widespread knowledge that vaccines prevent illness, having the term vaccine paired with the condition Ebola resulted in people’s very real fears about Ebola coloring their perception not only of the trial Ebola vaccine but also of other vaccines.

Although a small number of respondents forwarded accurate information about the vaccine trial (“They were trying to bring the vaccine, for Ebola to go away”) the following quotes were representative of the discussions:

To have the Ebola vaccine, we heard they will pay you first, and then you will pay for your own health. They make you sign the paper before they give it, so we were afraid there was something about it that was not altogether good for us. If they give you that vaccine, the Ebola will be in you for some time and then they will do an experiment to know whether it will kill you or not. They did it across the whole country. (Caregiver, Monrovia)

We heard about the Ebola vaccine and decided that if they came here, we would call the police. They did the trial to give Ebola to a person and see how they would feel and if they would die from Ebola. They did it on animals and humans. They said it was for everybody, even the children. (Caregiver, Bong)

There was a particularly strong and widespread narrative that suggested that the measles and polio campaign was a cover for targeting the country’s children. A community health worker in Nimba recounted how the outreach workers explained that “We were giving the vaccine because of measles, that in nearby communities children were dying from measles. But the community just kept asking us, ‘Are you sure? Are you sure it is just the measles vaccine?’” Similarly, a community leader in Monrovia, who had been a member of his community’s task force during Ebola, explained, “For the campaign, people had the notion that they were coming for the children, to kill the children with the immunizations.”

Having had time to reflect on the campaign and discuss the reasons for their non-uptake during the study’s focus groups, several caregivers described how they were now worried about the health of the children who had not received the vaccine. A caregiver in Margibi explained, “I am feeling bad that I didn’t take the child. I understand now, but I didn’t then, even though people had been coming around. I am praying that measles don’t come.” She concluded that she was considering going to the clinic (a 1-hour walk away) to “see if I can get it there.” But as a nurse at Ganta Community Clinic in Nimba explained:

Even though the campaign is over, we gave 52 vaccines yesterday. We still have the vaccine because it is routine, but we can only give it to children under 1 year. The campaign was for all children under 5 years, so even if mothers now decide they want their older children to be vaccinated, we can’t do it and they will have to wait until the next campaign.

Drivers of Immunization Uptake

A number of drivers were identified that led caregivers to positively engage with the measles, polio, and deworming campaign. One of the most dominant was knowledge and experience of accepting measles and polio vaccines prior to Ebola. As a mother in Monrovia emphasized, “We don’t worry about the measles and polio vaccine because we know it from before, from when the children were younger.” Other caregivers stressed that prioritizing preventive health care measures such as vaccines was part of responsibly caring for children. A mother in Margibi suggested, “If you don’t go, it is bad for the child. If the children have the vaccine and there is an outbreak of measles you will trick it.” A woman leader in the same focus group asserted, “Mothers know about measles, they have been experiencing it, so for the vaccine they were happy to carry their children. They know its importance.” This view was echoed by other participants. A mother in Nimba confirmed, “We can’t deny the vaccine, we have seen measles kill children. If you see it with your own eyes, you believe.” And affirming the importance of vaccination a mother in Monrovia stressed, “Measles can be prevented and cured, but Ebola will kill.”

Receiving the vaccine from a known and trusted source was also a key driver of uptake stressed by many participants. In Bong, a mother confirmed, “For me, the thing that made me brave was that it was the same person I went to see at the clinic.” In Margibi, a woman leader explained:

The reason all the children were vaccinated here—we went along with the vaccine. We were on our feet, we went around. If they didn’t see me at the vaccine time, they [the mothers] wouldn’t be brave. And also this man [County Health Team representative] who has been the supervisor from before [Ebola time] he was also with me, so the community people know us.

This view was emphasized by a community health officer in Nimba, who related his experience during the campaign:

In the bush, where we go for outreach, they are used to us. When we went for the campaign, the people kept far away, and then one girl finally came to speak to us. Then all the people went to her and asked if we were the ones from before [the health workers they knew] and she said yes, so then they started to come for the vaccinations because they trusted us.

Such accounts were in contrast to the distrust of health workers that was identified as a barrier to uptake (discussed previously) and emphasize the need for personal and face-to-face interactions and for prolonged engagement.

It was evident that it was not only trust in both the workers and their services that was important to community members but also confidence in who was giving the key messages about the campaign and through which information channels. Several respondents emphasized the need for “sensitization,” and most explained that gCHVs or “those in yellow T-shirts” had visited their communities prior to the campaign. The majority of respondents trusted the gCHVs and mobilizers and emphasized the need for interactions and prolonged engagement. As one community leader in Bong explained, “They said it was what we had taken before, that we should not be afraid. Our fellow black men encouraged us, my brothers can’t hold anything back, we know them.”

Many respondents heard about the campaign on the radio, and most regarded this as a reliable and trusted source of information (as also reflected in the Knowledge Attitudes and Practices [KAP] surveys and U-report data). As a caregiver in Bong explained:

On the radio, they said don’t be afraid, but to carry the children for measles and polio. There is the local community radio and there is the international radio for the whole nation, which we believe because that is how the country gets information.

Only a few respondents suggested distrust in radio health messaging. One mother in Margibi explained:

You used to be able to trust the radio, but during Ebola time we heard the radio plenty. We are human beings, so we are not satisfied, it is better if a person comes before you, then you will believe them.

Similarly, a father in Nimba concluded, “It is people like you who are on the radio. We are country people, so we won’t believe it. We want people to come and say it directly to us. Seeing is believing.”

Particularly in communities that were perceived by service providers to be more resistant, there were several rounds of social mobilization and multiple stakeholders advocated for the acceptance of the campaign. In one community in Bong, a community elder explained:

They had to come four times. Everybody talked to us, talk, talk, talk. It was not easy … The mobilizers came, and we heard it on the radio, and then they came from the Lutheran church, the pastor told us to take it, and then people came from the hospital and the superintendent and the chief came.

In addition to direct community engagement (by gCHVs, social mobilizers, health workers, and other stakeholders) and indirect engagement via the radio, a small number of respondents explained that the local town crier had also made announcements about the campaign, and one community leader recounted that there was a community meeting “but attendance was poor.” Mothers in one focus group in Monrovia discussed mobile dramas as being an effective way of raising awareness and providing information, “When they [the drama troop] came, then everybody came and gathered around. They played the drama, showed us, told us, taught us how to carry on.” It is interesting that no participant mentioned the banners, posters, flyers, or frequently asked questions sheets as a source of information.

Differing opinions were expressed as to whether communities were more resistant to the campaign in rural or urban areas. Many of the social mobilizers, including the CMCs and DMCs interviewed, concluded that people in rural areas were more suspicious of the vaccination. Several rural communities alluded to remote villages displaying higher levels of distrust. This was often explained in terms of a village’s limited access to information and services because “those communities are far from the road.” In contrast, health workers in Ganta suggested the opposite. Health staff at Ganta Community Clinic explained:

In the city is where we had the challenge, rather than in the villages. In the villages, people are under the control of their chief, and people listen to them more than in the city. Here people are individuals, and they say they know their rights.

Another key driver of positive uptake resulted from the “wait-and-see method” that the majority of respondents adopted. One mother from Bong explained, “We watched the other mothers and their children, and then when 2 days passed and nothing happened we thought it was alright to go.” Similarly, another community in Bong attested, “There is a nearby village that started to take it before us, and then we were happy to start taking it.” A father in Nimba explained:

After my wife took the child for vaccine, most of the mothers here asked her how our daughter is doing. They saw she was fine, so then they started to carry their own children, but we had to be the brave ones to go first.

A mother in Margibi concluded, “I saw a woman in the market who was not going to take her child, but I went to speak to her and showed her my child and encouraged her to carry and take the child.” This practice of “bearing witness” and using the “wait-and-see method” was also recognized and discussed by health workers. As one OIC concluded:

People were using the wait-and-see approach. Few people were coming, and others were watching them, and then if bad things didn’t happen, they would then come themselves. It was the continuous talking with people that made the difference, saying it was not a different vaccine but was the same that we used to give. In the first few days of the campaign, it was very slow. But on the last day, many people came, they left it until late to come, after they had seen other children be well.

In addition to drivers leading to positive action, participants also discussed instances when the threat of punitive measures may have pushed them toward accepting the vaccine. A mother in a focus group discussion in Monrovia concluded, “People said if you didn’t take the child for the yellow card [proof of vaccination], the hospital wouldn’t treat the child. The clinic people said they wouldn’t serve the child without the card. Why is that?” Similar examples were also given in Bong and Margibi counties, and when asked about this measure, health workers and social mobilizers (including the CMCs) replied, “We told them that to encourage them to come,” with apparent disregard for the misinformation conveyed.

In a focus group discussion in Nimba, participants discussed another example of coercive behavior and emphasized that it was not a constructive way to persuade them to accept the vaccine:

Somebody came and said if we didn’t take it [the vaccine] we would be fined or taken to prison. But with vaccines before Ebola, we didn’t have police of security, so why this time? The first vaccine team made a report to the superintendent and said they would take the town chief to prison if he didn’t bring the people. We didn’t feel fine, it was like Ebola was still here and they were trying fool us and force us. We changed because the other team that came spoke softly to us and said that these were the same as the vaccines from before, that in the villages around us, children were dying of measles so we needed to protect ourselves. If there is anything, then they need to come to us softly, because of the way that Ebola was and the way it killed, nobody should come to us loudly or strongly. People should come and talk to us, and they should give us the medicines like they used to, and then we are willing.

Community Recommendations for Future Interventions

During the course of the focus group discussions, community members made recommendations and forwarded community-based solutions to encourage engagement with future health interventions, including uptake during vaccination campaigns. The most frequently made recommendation was the integral use or involvement of the community. Across the study, respondents clearly articulated the need for communities to be active participants in an intervention rather than being conceived as passive recipients of a service delivered by outsiders.

The need to involve community leaders was emphasized repeatedly. In Bong, participants agreed, “You must involve the town chief, the elders, the women chair, the youth leaders, the local church leaders. You should train them to help combat illness.” In Margibi, one mother explained:

The gCHV came first and said the vaccine was coming, but some people argued. Then the gCHV called the town chief and he said to bring the children. You shouldn’t go directly to the people, it is better you go to a person that they trust and know, and that person, like the chief tells the people himself.

This view was echoed across all of the study sites. In Nimba, for example, participants in one focus group discussed the concerns they had when the vaccination team put up hand-washing stations and suggested that “Next time, you should give the buckets to the chief so that he puts the water in and puts the bucket out there himself, so that the people aren’t afraid and they trust it.”

Similarly, the need to incorporate known community members (in addition to community leaders) in social mobilization activities was stressed. It was widely agreed that:

We need somebody from our community to convince us. The community must select the person, it can’t just be anybody, it must not be an arrogant person, you can’t just select them. Due to our brothers and sisters sensitizing ourselves, we protect ourselves and we live through their advice.

In Bong, one mother concluded:

We trust our own people. Some of them went for training, so we believe them. You should use the same people in the future because we took our children as they told us to and by the grace of God they are fine.

In response, another mother confirmed, “You have to have people tell people: neighbors to neighbors, friends to friends, mothers to mothers.”

The involvement of mothers was particularly emphasized. Participants noted a high degree of trust between mothers due to shared experience and maternal responsibilities and in terms of “bearing witness,” as discussed previously. A mother in Margibi explained, “If you bring a mother here and she bears it, then I will have trust to carry my child. And then I can carry the news to other mothers in nearby communities where they have denial.” The need to include fathers in health education was also raised by several participants. As one mother in Margibi explained, “The father may say if you take my child for the vaccine and the child dies, that is your fault. It can be a woman or a man to talk to the fathers, but they should be included.”

In terms of different modes of community engagement, no mention was made of mobile or SMS communication channels that could provide an immediate feedback mechanism. Rather, participants stressed their preference for interpersonal or face-to-face dialogue. In one focus group discussion in Nimba, a mother asserted, “We want somebody to come here first to educate us, and then we can ask questions,” and a community elder responded, “When the people came, the mothers asked so many questions, it would fill your whole book.” The CMCs confirmed that communities were confident in asking questions and expressing their concerns during social mobilization activities, although a community member in Bong confirmed:

Yes, people came and explained to us, but they don’t stay for long or ask us in the way you have [for the study]. It is better like this [to have dialogue]. The town was worrying away, it is better that we can ask the questions we need to ask, to be clear about this, to take a long time for you to ask us and for us to ask you.

With regard to social mobilization activities, communities suggested that they should start earlier and go longer and that they should be ramped up during a campaign. This last point was also recommended by the CMCs who emphasized the importance of community engagement prior to, during, and after a campaign. Communities requested that social mobilization and health education activities happen in the evenings and on weekends rather than during the working day so that everybody (“whole families”) could be engaged. Several participants also stressed the need to leave the towns and villages and go to the farms to do effective mobilization. As one community elder in Bong concluded:

If people are farming it will be difficult to get them at their homes or in the village, so we suggest you go to the farms, particularly during khoo, the time when everybody goes to one person’s farm to help them on the land, and then we eat and drink. That would be the best time, because then people would be in the right mood and would listen to you.

Conclusion

The measles, polio, and deworming campaign that was rolled out across Liberia in May 2015 was a success. Coverage rates were high, and all participants in the rapid qualitative assessment (including those who had not presented their child) had knowledge of the campaign. Of the caregivers who had not presented their child, none mentioned financial barriers or issues of inaccessibility; rather, they explained their actions as a positive choice to avoid vaccination services—a choice made in the context of Ebola (whether they had experienced Ebola directly or indirectly). Even though Liberia was declared Ebola free on the second day of the campaign (May 9, 2015), this was not discussed by participants as a determining factor for uptake. Instead, the vaccine itself and the provision of the vaccination service were the dominant barriers.

A major component of the campaign, and one that contributed to its success, was effective community engagement led by the Ministry of Health and supported by UNICEF, who provided a high level of coordination, supervision, and technical support at national, county, and district levels. The various social mobilization activities were designed to be well integrated, mutually reinforcing, and frequently repeated. The key messages were consistent and raised awareness of the need to vaccinate children. Most importantly, the community engagement instilled a sense of trust in both the vaccine and the vaccine campaign, and communities repeatedly confirmed that it was this that had led them to accept the vaccines.

Part of this success was due to the fact that ongoing, routine social mobilization activities were supplemented and complemented by campaign-specific activities. The network of CMCs and DMCs provided UNICEF coverage and oversight at county and district levels and ensured that the organization could respond rapidly to emerging situations on the ground.

As the low coverage rates during both rounds of PIRI emphasized, the utilization of previously trusted health services (such as measles vaccination) was negatively affected by the Ebola outbreak. It colored communities’ perceptions of health workers and the services they provided, caused shifts in care-seeking practices, and elevated distrust in local and national authority. This study is specific to certain communities in Liberia where the Ebola vaccine trial had particular and far-reaching ramifications (unlikely to manifest in the same ways in Sierra Leone and Guinea because of the different trial strategies). However, the reintroduction of routine services across West Africa, particularly at a community level, must take into consideration the multitude of changes Ebola brought about. Extended community engagement, health promotion, and risk communication must mitigate the challenges faced, proactively encourage utilization and in so doing, ensure that communities are at the center of future policy and programing.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the County Health Teams, County Mobilization Coordinators, and District Mobilization Coordinators who were involved in this work. Particular gratitude is extended to the families and communities who participated in this study and readily shared their time and experiences.

Notes

1 http://apps.who.int/ebola/current-situation/ebola-situation-report-2-december-2015; http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6350a4.htm

2 The Reaching Every District initiative has been successfully implemented in Liberia. This strategy involves prioritizing low-performing districts by strengthening five important immunization functions at the district level: planning and management of resources, capacity building through training and supportive supervision, sustainable outreach, links between communities and health facilities, and active monitoring and use of data for decision making. Based on the data gathered in this study, however, it was not clear what impact Reaching Every District may have had on community perceptions of immunization, particularly in relation to outreach activities and mobile immunization teams.