Abstract

Background: The Community Benefits Health (CBH) program introduced a community-based behavior change intervention to address social norms and cultural practices influencing maternal health and breastfeeding behaviors in rural Ghana. The purpose of this study was to determine if CBH influenced maternal health outcomes by stimulating community-level support in woman’s social networks.

Methods: A mixed-methods study was conducted to evaluate changes in six antenatal/postpartum care, birth attendance, and breastfeeding behaviors in response to the CBH intervention and to assess how the program was implemented and to what extent conditions during implementation influenced the results.

Results: We found increases in five of the six outcomes in both the intervention and control areas. Qualitative findings indicated that this may have resulted from program spillover. We considered the dose of exposure to program activities and found that women were significantly more likely to practice maternal health behaviors with increased exposure to program activities while controlling for study area and time.

Conclusions: Overall, we determined that exposure to the CBH program significantly improved uptake of three of the six study outcomes, indicating that efforts aimed at increasing communication across women and their social networks may lead to improved health outcomes.

Background

Despite improvements in maternal health in Ghana over the last 20 years, maternal mortality remains high, and the country fell short in meeting the 2015 millennium development goal targets. The maternal mortality ratio fell from 634 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 319 in 2015, but this decline was insufficient to achieve the millennium development goal set for 2015 of 185 (WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division, Citation2015). High rates of poverty in rural areas coupled with cultural traditions that encourage women to request permission from their husbands or mothers in law prior to accessing health services undermine health outcomes, particularly in Ghana’s Upper West region (Ganle et al., 2015; Sumankuuro, Crockett, & Wang, Citation2017; Tolhurst, Amekudzi, Nyonator, Bertel Squire, & Theobald, 2008). While the community-based health planning and services (CHPS) strategy introduced through the Ghana health service (GHS) provides a platform to deploy health services in rural areas, there are still a number of social norms, and cultural practices at the community level that influence maternal health-seeking behavior including beliefs that husbands are not responsible for supporting their pregnant wives to maintain their antenatal schedules by providing finance, transport, or company (Nyonator, Citation2005; Sumankuuro, Crockett, & Wang, Citation2017). Several studies have shown that community beliefs and attitudes influence a woman’s decision to seek care (Kruk, Rockers, Mbaruku, Paczkowski, & Galea, Citation2010; Stephenson, Baschieri, Clements, Hennink, & Madise, Citation2006). Previous research in Ghana has found that women who live in communities where more women perceive higher use of facility delivery are more likely to deliver in a facility (Speizer, Story, & Singh, Citation2014). While these studies show an association between community attitudes and a woman’s health-seeking decisions, they do not explain how the woman engages with the community, including the nature of her relationships, the types of advice or support received, and the characteristics of her social network that may increase her receptivity to these attitudes. Several studies have investigated and found that network characteristics might be associated with the use of maternal health care-seeking behavior in developing-country settings (Adams, Madhavan, & Simon, Citation2002; Gayen & Raeside, Citation2007; Lowe & Moore, Citation2014). However, few, if any, studies have investigated interventions aimed to improve maternal health behaviors by influencing social networks and generating community-level social support.

The Community Benefits Health (CBH) program led by Concern WorldwideFootnote1 and their in-country implementing partner ProNet North collaborated with the GHS to introduce a community-based behavior change intervention to address the social norms and cultural practices influencing the utilization of select maternal health and breastfeeding behaviors. The rationale for CBH focusing on the community as a whole rather than individuals is grounded in an understanding that social relationships within the community have a strong influence on health behaviors (Valente, Glanz, Rimer, & Viswanath, Citation2015). At the heart of CBH is the focus on normative behavior change, which emphasizes and takes advantage of social structural factors that influence behavioral choices, including network structures, relationships, and equitable availability of social and material resources. By shifting attitudes and behaviors of key members of the community, social norms around care-seeking behavior may also improve, resulting in improved health outcomes. The purpose of this study is to determine if the CBH program influenced maternal health outcomes by stimulating community-level support in woman’s social networks.

Description of the Intervention

The CBH program included two components. The first component was a community-based incentive. Community members selected a borehole or emergency transport system as an incentive that was promised to the entire community if they fulfilled certain conditions over a 2-year period, such as having men participate in educational meetings on maternal and child health issues.Footnote2 By incentivizing behavior change, CBH aimed to encourage the entire community to support women in adopting improved maternal health and breastfeeding behaviors and swiftly change community-wide social norms by the end of the 2-year program. The second component of the intervention was a comprehensive health messaging strategy, which included use of video and drama presentations at the community level, home visits from peer educators, community-based meetings facilitated by community health officers (CHOs) and radio programs. The CBH program was implemented between April 2014 and March 2016 in the Jirapa, Lambussie, and Wa West districts of Ghana’s Upper West region. Nine communities in the three districts were identified through consultations with government officials and community leaders during visits to Ghana by program staff in the first quarter of 2013. Formative research determined that the communities were similar in sociodemographic composition.

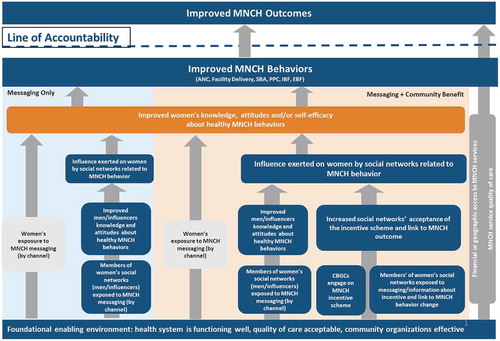

The CBH program theory of change, shown in , presents the two intervention arms and the pathways that we anticipated the communities would follow to achieve behavior change. The CBH program was guided by social network theory and the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991; Valente et al., Citation2015). The program encompassed elements of social network theory, as it recognized that women take actions based on their network environment or who they are connected to. These connections may provide a woman with information or advice or other forms of tangible support that will enable her to practice a specific behavior. If a person in a woman’s network holds a position of influence, such as a community leader or a partner, this may have a greater influence on a woman to adopt a behavior. Finally, shifts in these connections have the potential to change social norms.

In order to stimulate the flow of support between these network connections, the program introduced messaging activities that sought to address the knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy of the individual actors, as outlined in the theory of planned behavior. As mentioned earlier, the messaging activities were implemented across two intervention arms. The program sought to further catalyze these relationships in one of the two intervention arms by providing a community-based incentive. In these communities, the program sought to understand if the “promise” of a community-based incentive, managed by a community governance committee and supported by a woman’s social network, could more effectively influence her knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, and ultimately behaviors compared with those that were only exposed to traditional behavior change messaging activities.

The mixed-methods evaluation seeks to describe how and if the CBH program was implemented according to the theory of change and provides evidence on the effect of this approach and the factors that explained how and why these changes occurred. Specifically, this article seeks to answer the following questions: (1) Did network characteristics affect maternal health behavior?; (2) How did social networks influence health behaviors?; and (3) What was the effect of the CBH activities on maternal health care and breastfeeding behaviors?

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a mixed-methods study to evaluate the effectiveness of the CBH program in three districts located in the Upper West region of Ghana from November 2013 to May 2016. The purpose of the mixed-methods design was to assess changes over time of whom women spoke with about pregnancy and breastfeeding behaviors and to assess changes in maternal heath behaviors using quantitative methods while explaining how and why changes occurred using qualitative methods. Qualitative and quantitative data were collected at separate times. We collected qualitative data during program implementation whereas the baseline quantitative survey was administered before program implementation and the end line was administered at the conclusion of implementation. Populations overlapped in that a subsample of men and women who had a child under the age of 2 were asked to participate in focus groups.

Quantitative

The quantitative component of the study was composed of a three-arm pre/post quasi-experimental survey. The unit of assignment was the CHPS zone, which included the catchment area around a CHPS facility. CHPS zones included in the program ranged in population from 763 to 3164 and served anywhere from 1 to 10 communities. The first intervention arm included three CHPS zones exposed to the messaging strategy and the incentive. The second arm included three CHPS zones only exposed to the messaging strategy. The remaining three CHPS zones were assigned to the control group. The purpose of this design was to allow the program, through its evaluation strategy, to tease out the added value of attaching an incentive to the comprehensive messaging approach on use of skilled birth attendance (SBA), antenatal and postpartum care (PPC), and breastfeeding behaviors.

The sample size calculation was based on the prevalence of the rarest outcome (i.e., proportion of mothers receiving PPC within 48 hours after birth) which was 15 percent at baseline and considered to possibly increase to 20 percent at end line with 90 percent power at the 95 percent significance level. We also estimated that the design effect due to clustering of events within CHPS zones and households to be 1.23 and that the nonresponse rate would be 10 percent. Based on these assumptions and using Stata 11.2 statistical software, the required sample size for the study was estimated to be 1746. This translates to about 582 respondents from each arm of the project for the baseline and the end line surveys. Population estimates from the GHS indicated that the actual target population of women between the ages of 15 and 49 was close to the desired sample size. As a result, the study team opted to conduct a census of women between the ages of 15 and 49 who had given birth to at least 1 child in the 2 years preceding the survey. Interviewers identified eligible respondents by going door to door in the sampled program arm and comparison communities.

Kintampo Health Research Centre was responsible for the baseline data collection, and endogenous development services managed end line data collection. The research partners recruited interviewers locally and trained them to move interviewees to secluded spots out of earshot from family to ensure confidentiality. Interviewers administered the surveys using mobile phones. Baseline data collection took place between November 2013 and February 2014, with 99 percent completed by 10th January 2014. End line data collection began in April 2016 and was completed in May 2016.

Key Health Practices

We selected a number of indicators previously identified to influence maternal and infant mortality, including early initiation of antenatal care (ANC), four or more ANC visits (ANC4), SBA, receiving PPC within 48 hours of delivery, early initiation of breastfeeding (IBF), and exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) for the first 6 months. These indicators are further described in Appendix 1. Indicators selected to measure program impact were based on a number of factors. Many health indicators in the region were already quite high according to the 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey or were heavily influenced by supply-side issues (Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Ghana health service (GHS) and ICF Macro, Citation2009). We selected indicators that had a lower baseline value in the region, were less likely to be influenced by supply-side issues, did not require an extremely large sample size to measure change, and seemed to be impeded by sociocultural issues as identified in the formative research.Footnote3 Data collection and variable construction for the key outcomes followed global standard questions and sequences employed by the Demographic and Health Surveys.Footnote4

We assessed the effect of social network characteristics on pregnancy and breastfeeding behaviors by considering five characteristics that have previously been used to describe social networks (Heaney & Israel, Citation2008). The network characteristics considered in the analysis and the survey questions used to collect the information are presented in .

Table 1. Study questions used to measure social network characteristics

Qualitative

The qualitative component was composed of focus group discussions and key informant interviews to assess how the program was implemented and to what extent conditions during implementation influenced the results. Focus group discussions were conducted with community members in six communities participating in the intervention, three in each intervention arm. Key informant interviews were conducted with program staff at ProNet North, Concern Worldwide, and the district health management team.

Trained moderators from endogenous development services facilitated focus group discussions of 8–10 participants among groups of women and men who had a child in the 2 years preceding the interview and among influencers in the community such as village chiefs and traditional birth attendants. We purposively selected respondents to represent a mix of groups and partners participating in the program intervention. We interviewed a total of 65 community influencers, 52 fathers, 61 mothers, and 5 program and GHS staff at the conclusion of the intervention in March 2016. Moderators conducted the interviews with community members in the local language of Dagaare with permission from respondents. Interviews were recorded using a digital audio recorder and translated and transcribed into English.

Analysis

To measure the program effect on health outcomes, we estimated logistic regression models on each health behavior while controlling for demographic characteristics of age, parity, religion, educational level, and network size. We included variables to control for listening to the radio in the past week to account for program messages delivered by radio. We also accounted for women’s group participation because these groups were used as a means to mobilize community members for group messages. As explained further below, we found considerable evidence indicating diffusion of intervention messages to control areas. To adjust for this effect, we controlled for the study period (baseline and end line) and constructed an exposure variable based on the dose of messaging activities received by each respondent to measure program effects (Freedman, Takeshita, & Sun, Citation1964). Each respondent was asked at end line if they participated in a project messaging activity and, if yes, the number of times they had participated in this activity. We ran factor analysis on the number of times each respondent had participated in a project messaging activity, as well as if they had heard of the community incentive, and then calculated an exposure variable as the mean of the individual items. We also controlled for the messaging and messaging-plus-incentive study arms. presents characteristics of the study participants by study arm and period.

Table 2. Description of respondents

To determine the effect of social network characteristics on program outcomes, we applied the logistic regression equation on a subset of women who had “… chatted with [someoneFootnote5 ] about breastfeeding or receiving care before or after pregnancy.” In these models, our key predictor variables were social network characteristics, including the network partner’s sex, educational level, marital status, where they lived, the nature of the relationship, whether the woman gave or received information from the network partner, and whether or not the network partner was an acquaintance or a close friend. We included the same demographic and exposure variables as in the full model.

We used thematic analysis techniques to identify themes emerging from the qualitative data. We focused on each component of the theory of change and searched the data using the established codes as well as deductive codes that emerged to develop an understanding of the topics. Findings were described and compared across subgroups. We then triangulated results from the qualitative and quantitative data to develop a more comprehensive understanding of how the program was implemented and what factors related to the context and implementation influenced the results that were derived.

Results

Did Network Characteristics Affect Maternal Health Behavior?

presents results from the model assessing the effects of social network characteristics on health behaviors among women who named at least one person that they “… chatted with about breastfeeding or receiving care before or after pregnancy.” Our key predictor variables were social network size and characteristics of those named, including the sex, marital status, education, where they lived, the nature of the relationship, whether the woman gave or received information from the network partner, and whether or not the network partner was an acquaintance or a close friend. We controlled for demographic characteristics, including age, education, religion, parity, and whether they were in a woman’s group or listened to the radio in the last week. Results are presented by the five social network characteristics described in .

We considered the demographic characteristics of the person that a woman chatted with and found mixed results across outcomes for network partner demographic characteristics such as marital status, sex, and education level. For example, women were significantly more likely to initiate early breastfeeding if their network partner was married (AOR = 1.55, p < 0.02), were more likely to use a skilled birth attendant if their network partner was male (AOR = 2.25, p < 0.01) and less likely to attend early ANC if their partner had higher education (AOR = 0.73, p < 0.01). When considering the relationship that a woman had with her network partner, we found women were more likely to use PPC if they spoke with a health provider compared with her partner (AOR = 3.02, p = 0.03). We also found that women whose network partner lived in the same district or somewhere else were less likely to practice a number of behaviors including ANC4 and IBF compared with women who spoke with someone in their same household.

If a woman had an intimate relationship with the network partner (i.e., whether they were a friend or acquaintance), there was no effect on most health behaviors. These findings were consistent with our qualitative data. A number of community members spoke of the increased discussions on maternal, newborn, and child health (MNCH) issues throughout the community and attributed this increase to the program activities. As channels for sharing information on MNCH issues increased, information diffused across the community, and discussions are now more commonly heard on the farm, at women’s groups meetings, at the markets, funerals, water sources, and even among men at pitoFootnote6 bars. Community members are now taking initiative to discuss these issues more openly. “We used to be afraid of talking to someone’s wife because you could be accused of negative things. Because of CBH we freely talk to people without fear. Old and young men and women are talking about MNCH in the community. We now know the need for discussion.” (Dabo Influencer)

While program community engagement efforts focused on a specific group of CHPS zones, the program was unable to prevent interaction at shared venues, which resulted in information being shared across the three study arms. Community members often attend funerals or frequent markets in neighboring communities. Respondents in the intervention communities spoke of members from surrounding comparison communities asking questions about the program and said that they attended videos, dramas, and durbarsFootnote7 in the intervention communities. One woman from Saawie, an incentive community, said “Every community member and other people from the surrounding villages are aware of CBH because of the videos, dramas, monthly community meetings and the winning durbar/events.” Footnote8 The proximity of communities from the messaging and incentive arms also created some unanticipated effects. In some messaging communities, there was a sense that if they outperformed the incentive communities they might receive a benefit as well. One leader from Dabo, an incentive community, reported that he had “heard that other communities are involved in CBH activities but they are not going to get a benefit, so they are also working hard to convince Pronet to give them a benefit.”

We also found that women who said they had spoken to someone about pregnancy and breastfeeding and practiced IBF were less likely to have received advice or information (AOR: 0.68, p < 0.05). This result was also supported through our qualitative interviews. Several community members felt that the program interventions encouraged people to more actively provide advice to others in the community in a way that they would not have intervened previously. In the past, it may have been seen as negative to intervene on pregnancy and breastfeeding issues, but now many community members see it as a communal responsibility to support the health of a mother and the growth of the child. “We give advice because we want the child to grow and benefit the whole community. It is a form of communal ownership. So if a child grows, I am sure he will benefit the community as a whole.” (Tapumu influencer) “I usually offer the advice out to pregnant women because I want the safe delivery for the woman. I have the strong conviction that the child given birth to will serve the greater community in a very positive way. In situations where the woman loses the baby and/or in grave situation dies in the process, it will be a serious blow to the people of the community… We also want to continue to multiply. That is why we offer pieces of advice to ensure safe delivery.” (Kenee influencer)

Table 3. Odds ratio of social network characteristics and effects of intervention by maternal and breastfeeding outcomes8

How Do Social Networks Influence Health Behaviors?

Findings from the qualitative research indicated that the program was more effective in building support among husbands. As husbands were exposed to program messages, discussions on MNCH issues increased between husbands and wives. “Men scarcely discussed these issues with their wives and even among themselves. But today, discussions among men and women are prevalent as well as between fellow men. ” (Tapumu influencer) Exposure to videos and flipcharts that demonstrate how women and men can talk about pregnancy and childbirth helped to create an environment where husbands and wives have something in common to discuss. “Now I can discuss weighing issues (ANC) with my husband freely because he has been part of the meetings and knows the targets and benefits. Before the project, we only talked about health when the baby was sick.” (Dabo woman) These improved opportunities for dialogue strengthened a woman’s role in household decision-making. “Men don’t dominate decisionmaking with regards to the health of the baby and the kind of jobs to do while pregnant. The videos and pictures have helped to increase communication between men and women” (Saawie influence.)

Finally, the exposure to information also enabled men to take an active role in the care of their pregnant wife and child by providing them with the knowledge needed to reinforce important health behaviors. “My husband and I now talk about the health more than before because he has been a part of all the sensitization meetings and video shows that have been held regarding maternal and child health in this community. He insists that you do exactly what the nurses have said, especially when I have to go for [ANC] and breastfeeding the baby he doesn’t joke with them.”´ (Dabo woman) Attending the facility with the woman also ensured there were no misunderstandings between the husband and wife regarding advice from the CHO. “We used not to accompany them to the health facility, but the CHO made us to understand that there is a lot of advice our wives used to keep to themselves, although we needed to know about it. Also, if my wife goes to the facility alone, she can come back and say something and I may not believe. For example, the CHO can advise her to eat eggs but because I was not there, I will not take her serious and may even scold her. But, if you the husband is present at the facility, you will hear it personally.” (Dabo man)

What Was the Effect of the CBH Activities on Maternal Health Care and Breastfeeding Behaviors?

We estimated logistic regressions to look at the effect of the CBH interventions on each of the key outcomes and ran predicted probabilities on the study sample by study arm and period. Our key predictors were exposure to the intervention mean factor score and whether or not a woman was in a messaging or messaging-plus-incentive study arm and period. We controlled for age, education, religion, parity, whether or not she attended a woman’s group or listened to a radio in the last week, and network size. Additional social network characteristics were not included because these questions were asked only among the subset of women who identified a network partner.

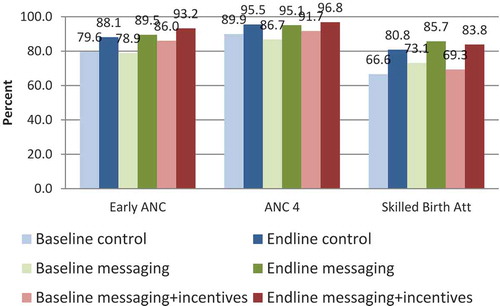

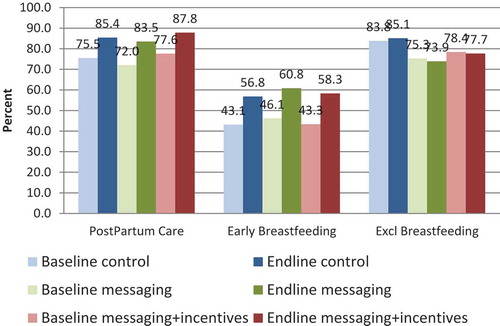

Insert and predicted probability of study arms and program effect about here.

Table 4. Odds ratio of demographic characteristics and effect of intervention by maternal and breastfeeding outcomes

Fig. 3. Adjusted effect of the CBH program on postpartum care, early initiation of breastfeeding, and exclusive breastfeeding.

Overall, we found improvements from baseline to end line across all outcomes and all study groups except EBF as shown in and . For ANC4, we found an increase of approximately 5 percentage points in the messaging-plus-incentive communities and the control and an 8 percentage point increase for the messaging only group. For SBA, we found among the messaging-plus-incentive group an increase from 70 percent at baseline to 83 percent at end line and a similar increase among the control communities from 67 percent at baseline to 80 percent at end line. We also found significant improvements across study arms for early IBF but limited changes in EBF.

presents the odds ratio of demographic and study characteristics for each study outcome. Across three of the six study outcomes, we found that women who were exposed to the intervention activities were significantly more likely to have practiced improved health outcomes. We found an increased odds of using early ANC, ANC4, and SBA among women who received a greater dose of messaging activities (early ANC (AOR = 1.34, p = 0.02), ANC4 (AOR = 1.81, p < 0.001), and SBA (AOR = 1.32, p < 0.01).

Discussion/Conclusion

The CBH program worked at the community level in the Upper West region of Ghana to introduce activities aimed at changing social norms in order to improve maternal health-seeking behaviors. The program worked thoroughly and successfully to build support with traditional authorities and structures during implementation and generated considerable enthusiasm in communities where the nonmonetary community-based incentive was introduced. Similar to previous studies, we found the efforts placed in gathering support from local stakeholders translated into increased participation in program activities at the community level (Rogers Ayiko, Citation2015). Garnering support from communities through meetings and messaging activities appeared to change social norms by increasing the number of people women discussed pregnancy and childbirth with and the direction of these discussions (i.e., women receiving more advice and support in the intervention communities) over the study period.

The program aimed to catalyze community support beyond what could be achieved through traditional behavior change messaging strategies by introducing a community-based nonmonetary incentive. Nonmonetary incentives have been deployed in a variety of settings and have shown promising results in increasing participation and improvements in health outcomes (Khogali et al., Citation2014; Olken, Onishi, & Wong, Citation2011; Weeden, Bennett, Lauro, & Viravaidya, Citation1986; WHO Regional Office of Africa, Citation2013). The promise of the incentive generated enthusiasm within the communities during the project, and we found qualitative evidence to support that communities who received the incentive were more likely to adopt improved health outcomes but this was not supported quantitatively. Several issues also emerged with the introduction of the incentive including confusion over when the incentive should be received, which challenged cultural norms and the overall complexity of explaining to predominantly illiterate communities the need to reach targets over time in order to receive the incentive. Program implementers spent a considerable amount of time at the onset of the program explaining how communities would receive the incentive, which may have mitigated some of the results.

A major focus on the CBH messaging activities was to encourage male involvement during pregnancy and childbirth. Previous studies have found that introducing activities that encourage male involvement can support improvements in maternal health outcomes (Kraft et al., 2014; Story et al., 2012; Story and Burgard, 2012). Many women reported through our qualitative data that they received greater support from their husbands, including accompanying their pregnant wives to the health facility. However, these findings did not emerge when tested quantitatively, and results were more mixed. This may have been because the end line survey was conducted during a period of seasonal migration, and many husbands may have been temporarily absent from home at that time.

Limitations

The program worked closely with the GHS to design and implement activities and as a result was required to work in three separate districts. With the goal of evaluating program activities, it was important to ensure that there were three study arms so that we could tease out the added benefit of including an incentive while providing a comparison group composed of communities that did not receive an intervention. The complexity of the study design coupled with the need to address GHS needs created some challenges for the evaluation and program implementation. For program implementation, the proximity of communities participating in the program created an issue where messaging communities felt frustrated that they were not receiving an incentive. The program responded by encouraging the messaging communities to outperform the incentive communities. We also found evidence of spillover across study arms due to the proximity of the study sites. These contextual factors may have influenced the findings that there were improvements across all three study arms and may have mitigated the program effect for communities receiving the incentive. Additional factors that may have mitigated the results were that there were some resource flow constraints that interrupted program activities during 6 months of the 2-year program and the fact that some of the behaviors were high at the onset of activities, which made it challenging to register a significant change over time.

Conclusion

We determined that exposure to the CBH program significantly improved uptake of three of the six study outcomes. Among women who said they spoke with at least one partner about pregnancy or breastfeeding, we observed an increased likelihood in practicing ANC4, SBA and IBF, indicating that efforts aimed at increasing communication across women and their social networks may lead to improved health outcomes. The full impact of increased communication may have been mitigated by the existing high baseline values of early ANC, ANC4, and PPC.

Abbreviations

| ANC | = | antenatal care |

| ANC4 | = | four or more ANC visits |

| AOR | = | adjusted odds ratio |

| CBH | = | Community Benefits Health |

| CHO | = | community health officer |

| CHPS | = | community-based health planning and services |

| EBF | = | exclusive breastfeeding |

| GHS | = | Ghana health service |

| IBF | = | initiation of breastfeeding |

| MNCH | = | maternal, newborn, and child health |

| PPC | = | postpartum care |

| SBA | = | skilled birth attendance |

Declaration of interest

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Availability of data and material

The data that support the findings of this study were used under license for the current study and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We also thank our local research partners Kintampo Health Research Centre and Endogenous Development Services, who implemented the data collection in the field.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Leanne Dougherty

LD led study design development, analyzed data, drafted manuscript, gave final approval for manuscript.

Emily Stammer

ES assisted with tool development, supervised data collection, analyzed data, provided feedback on manuscript, made revisions to manuscript.

Emmanuel Derbile

ED led and supervised data collection, provided feedback on manuscript

Martin Dery

MD, WY, JO, DG, JF provided feedback on manuscript.

Wahid Yahaya

MD, WY, JO, DG, JF provided feedback on manuscript.

Dela Bright Gle

MD, WY, JO, DG, JF provided feedback on manuscript.

Jahera Otieno

MD, WY, JO, DG, JF provided feedback on manuscript.

Notes

2 Additional details on the incentive selection are described in the report “The Use of Design Thinking in MNCH Programs: A Case Study of the Community Benefits Health (CBH) Pilot, Ghana.”(Kanagat & LaFond, Citation2018).

3 “Report on Location Scoping Trip to Upper West Region for the Community Benefits Health Project” by Laura McGough.

5 This person is referred to as a network partner.

6 A locally made millet beer.

7 Type of traditional community meeting called together by village elders in Ghana.

8 Demographic variables controlled for in included age, education, parity, women’s group attendance, religion, and whether or not they had listened to the radio in the last week.

References

- Adams, A. M., Madhavan, S., & Simon, D. (2002). Women’s social networks and child survival in Mali. Social Science & Medicine, 54(2), 165–178. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00017-X

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Freedman, R., Takeshita, J. Y., & Sun, T. H. (1964). Fertility and family planning in Taiwan: A case study of the demographic transition. American Journal of Sociology, 70, 16–27. doi:10.1086/223734

- Ganle JK, Dery I. (2015) “What men don”t know can hurt women’s health’: a qualitative study of the barriers to and opportunities for men’s involvement in maternal healthcare in Ghana. Reprod. Health. 12, 93.

- Gayen, K., & Raeside, R. (2007). Social networks, normative influence and health delivery in rural Bangladesh. Social Science & Medicine, 65(5), 900–914. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.037

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Ghana Health Service (GHS) and ICF Macro. (2009). Ghana demographic and health survey 2008. Accra, Ghana: GSS, GHS and ICF Macro.

- Heaney, C., & Israel, B. (2008). Social networks and social support. In: Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice (4th ed., pp. 189–210). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Kanagat, N., & LaFond, A. (2018). The use of design thinking in MNCH programs: A case study of the Community Benefits Health (CBH) Pilot, Ghana. Rosslyn, VA: John Snow, Inc.

- Khogali, M., Zachariah, R., Reid, A. J., Alipon, S. C., Zimble, S., Gbane, M., … Harries, A. D. (2014). Do non-monetary incentives for pregnant women increase antenatal attendance among Ethiopian pastoralists? Public Health Action, 4(1), 12–14. doi:10.5588/pha.13.0092

- Kraft JM, Wilkins KG, Morales GJ, Widyono M, Middlestadt SE. (2014). An Evidence Review of Gender-Integrated Interventions in Reproductive and Maternal-Child Health. Journal of Health Community, 19, 122–41.

- Kruk, M. E., Rockers, P. C., Mbaruku, G., Paczkowski, M. M., & Galea, S. (2010). Community and health system factors associated with facility delivery in rural Tanzania: A multilevel analysis. Health Policy, 97(2–3), 209–216. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.05.002

- Lowe, S. M. P., & Moore, S. (2014). Social networks and female reproductive choices in the developing world: A systematized review. Reproductive Health, 11, 85. doi:10.1186/1742-4755-11-85

- Nyonator, F. K. (2005). The Ghana community-based health planning and services initiative for scaling up service delivery innovation. Health Policy and Planning, 20(1), 25–34. doi:10.1093/heapol/czi003

- Olken, B., Onishi, J., & Wong, S. (2011). PNPM generasi: Final impact evaluation report. Jakarta, Indonesia: The World Bank.

- Rogers Ayiko, B. B. (2015). Perspectives of local government stakeholders on utilization of maternal and child health services; and their roles in North Western Uganda. International Journal of Public Health Research, 3(34), 135–144.

- Speizer, I. S., Story, W. T., & Singh, K. (2014). Factors associated with institutional delivery in Ghana: The role of decision-making autonomy and community norms. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14, 398. doi:10.1186/s12884-014-0398-7

- Stephenson, R., Baschieri, A., Clements, S., Hennink, M., & Madise, N. (2006). Contextual influences on the use of health facilities for childbirth in Africa. Journal Information, 96(1). Retrieved from http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/AJPH.2004.057422

- Story W, Burgard S, Lori J, Taleb F, Ali N, Hoque DE. (2012). Husbands’ involvement in delivery care utilization in rural Bangladesh: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 12, 28.

- Sumankuuro, J., Crockett, J., Wang, S. (2017). The use of antenatal care in two rural districts of Upper West Region, Ghana. PloS One, 12(9), e0185537. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185537

- Tolhurst R, Amekudzi YP, Nyonator FK, Bertel Squire S, Theobald S. (2008). “He will ask why the child gets sick so often”: The gendered dynamics of intra-household bargaining over healthcare for children with fever in the Volta Region of Ghana. Soc. Sci. Med. 66, 1106–17.

- Valente, T. W., Glanz, K., Rimer, B. K., & Viswanath, K. (2015). Social networks and health behavior. Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice, 205-222.

- Weeden, D., Bennett, A., Lauro, D., & Viravaidya, M. (1986). An incentives program to increase contraceptive prevalence in rural Thailand. International Family Planning Perspectives, 12(1), 11. doi:10.2307/2947624

- WHO Regional Office of Africa. (2013). Community performance based financing to improve maternal health outcomes: Experiences from Rwanda. Brazzaville, Republic of Congo.

- WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. (2015). Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015 Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Appendix 1: Description of Key Outcomes

Early initiation of antenatal care (ANC): Proportion of women age 15–49 who had a live birth in the 2 years preceding the survey who initiated ANC attendance within the first 3 months of pregnancy for the most recent pregnancy.

ANC 4: Proportion of women age 15–49 who had a live birth in the 2 years preceding the survey who had received a minimum of four antenatal care visits with any provider for the most recent pregnancy.

Skilled birth attendance (SBA): Proportion of women ages 15–49 with at least 1 live birth in the 2 years preceding the survey who were assisted by a skilled provider at the most recent birth.

Postpartum care (PPC): Proportion of women age 15–49 who had a live birth in the 2 years preceding the survey receiving a health checkup in the first 48 hours after delivery for the most recent birth.

Early initiation of breastfeeding (IBF): Proportion of women ages 15–49 with at least 1 live birth in the 2 years preceding the survey who initiated breastfeeding within 30 minutes of the most recent birth.

Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF): Proportion of children 0–5 months born in the 2 years preceding the survey who received only breast milk in the 24 hours preceding the survey.