Abstract

Trust and mistrust influence the utilization of health services, the quality of overall healthcare, and the prevalence of health disparities. Trust has significant bearing on how communities, and the individuals within them, perceive health information and recommendations. The People and Places Framework is utilized to answer what attributes of place threaten community trust in public health and medical recommendations.

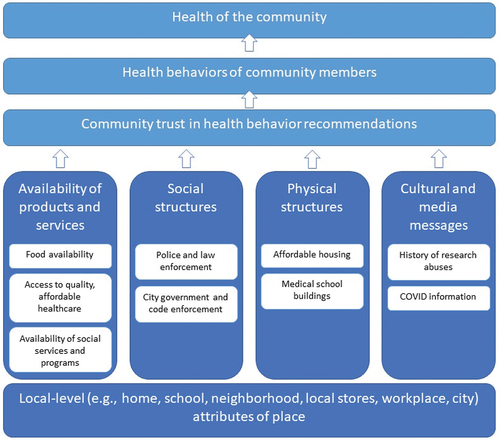

Augusta-Richmond County is ranked among the least healthy counties in Georgia despite being home to the best healthcare-to-residence ratios and a vast array of healthcare services. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 31 neighborhood residents. Data were analyzed using the Sort & Sift, Think & Shift method. Threats to community trust were identified within four local-level attributes of place: availability of products and services, social structures, physical structures, and cultural and media messages. We found a broader web of services, policies, and institutions, beyond interactions with health care, that influence the trust placed in health officials and institutions. Participants spoke to both a potential lack of trust (e.g. needs not being met, as through lack of access to services) and mistrust (e.g. negative motives, such as profit seeking or experimentation). Across the four attributes of place, residents expressed opportunities to build trust. Our findings highlight the importance of examining trust at the community level, providing insight into an array of factors that impact trust at a local level, and extend the work on trust and its related constructs (e.g. mistrust). Implications for improving pandemic-related communication through community relationship building are presented.

Since March 2020, American public health, medical, and governmental organizations have struggled to effectively communicate pandemic-related health information (Calvillo, Ross, Garcia, Smelter, & Rutchick, Citation2020; Chandler et al., Citation2021; Grimes, Citation2021; Iyasere et al., Citation2021). From disseminating information about risk of transmission to effectiveness of pandemic response strategies, the public has responded to COVID-19 information with not only hesitance but resistance (Ma & Ma, Citation2021; Nguyen, Nguyen, Corlin, Allen, & Chung, Citation2021; Ruiz & Bell, Citation2021; Xu & Cheng, Citation2021). Augusta, Georgia, was one community that resisted pandemic response strategies (Ledford et al., Citation2022; Moore et al., Citation2021).

In a previous study on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, we uncovered ways in which local and regional history influence community trust and relationships with medical institutions (Ledford et al., Citation2022). The close proximity to Tuskegee, Alabama, seemed to magnify the lasting impact of the Tuskegee Syphilis study on local perceptions of science and medicine. Participants also questioned the motives of the medical college, while retelling the college’s history of using grave robbers to pillage Black cemeteries to acquire human remains to teach anatomy (Bones in the Basement: Postmortem Racism in Nineteenth Century Medical Training, Citation1997). These historical examples of abuse influenced attitudes and trust of science and medicine.

Trust and mistrust influence the utilization of health services (Griffith, Bergner, Fair, & Wilkins, Citation2021; Trachtenberg, Dugan, & Hall, Citation2005) and the quality of overall health care, (Armstrong et al., Citation2006; Benkert, Cuevas, Thompson, Dove-Meadows, & Knuckles, Citation2019) and the prevalence of health disparities (Jaiswal & Halkitis, Citation2019). Trust may also have significant bearing on how communities, and the individuals within them, perceive health information and recommendations. To date, health communication scholarship largely focused on trust in information sources via source credibility (Carpenter et al., Citation2011; De Meulenaer, De Pelsmacker, & Dens, Citation2018; Emmers-Sommer & Terán, Citation2020), including trust in family and friends as sources of information (Freed, Clark, Butchart, Singer, & Davis, Citation2011; Yang, Chen, & Wendorf Muhamad, Citation2017); trust between patients and clinicians (Hesse et al., Citation2005; Peek et al., Citation2013; Wilk & Platt, Citation2016); or trust in government (Park & Lee, Citation2018). The COVID-19 pandemic renewed efforts to examine issues around trust, with studies highlighting the importance of individual trust in communicating public health and medical recommendations throughout the pandemic (Bogart et al., Citation2021; Chan, Citation2021; Cokley et al., Citation2022). That approach maintains focus on individual-level factors, along with interpersonal factors and societal factors (e.g., government), and neglects community-level factors. In the midst of calls for a lesson of the pandemic to be increased engagement with communities moving forward (Palmedo, Rauh, Lathan, & Ratzan, Citation2022), we must have a more thorough understanding of community trust. One way to elucidate community trust in health recommendations during the pandemic is to examine the role of place.

Few studies, however, focus on the place factors that influenced health decisions through the pandemic. The People and Places Framework, an applied ecological public health model, describes how the health of populations is influenced by attributes of people in the population, attributes of places where the population live and work, and interactions between the attributes of people and places (Maibach, Abroms, & Marosits, Citation2007). In the framework, people-oriented attributes include individual-level factors (e.g., affect, motivation, demographics), social network factors (e.g., size, connectedness), and cultural and social norms (e.g., social capital, social cohesion, collective efficacy). Place-oriented attributes exist at the local level (e.g., home, neighborhood, city) and distal level (e.g., state, region, nation). Attributes of place include the availability of products and services, physical structures, social structures (e.g., laws, policies, enforcement), and media and cultural messages (Cohen, Scribner, & Farley, Citation2000). This investigation utilizes the People and Places Framework to answer:

What attributes of place threaten community trust in public health and medical recommendations?

Materials and Methods

This qualitative investigation is part of a capacity building project in the neighborhoods surrounding the Medical College of Georgia (MCG) (Ledford, Citation2021). MCG is Georgia’s only public medical school, training medical students for nearly 200 years. Augusta University (AU) Institutional Review Board determined the project does not meet the definition of human subject research. Community leader interviews began in summer 2021, followed by interviews with neighborhood residents. This process contributed to development of the Co-Researcher Activation Network (CRANE), which identifies community health concerns, develops research questions, and creates community-generated solutions. Informed by The People and Places Framework (Maibach, Abroms, & Marosits, Citation2007), “community” refers to a group of people, and “neighborhood” refers to a geographic location. Although neighborhood boundaries are permeable and neighborhood residents may work, shop, recreate, and seek medical care in different neighborhoods, individual identity, or community, is frequently linked to the places in which people stay or call home (Gram‐hanssen & Bech‐danielsen, Citation2004; Peng, Strijker, & Wu, Citation2020).

Augusta-Richmond County (pop: 201,196 (QuickFacts Augusta-Richmond County consolidated government, Georgia)) is the 121st largest incorporated place in the U.S. (City and Town Population Totals: 2020–2021). The County has some of the best primary care physician to resident (1:900), mental health provider to resident (1:310), and dentist to resident (1:480) ratios in the state (County Health Rankings and Roadmaps, Citation2022). However, the state’s medical school neighbors some of the state’s unhealthiest places. According to the 2022 County Health Rankings (County Health Rankings and Roadmaps, Citation2022), it is ranked among the least healthy counties in Georgia (124 of 159 counties); 7.6% of residents are unemployed, 39% of people under the age of 18 live in poverty, 16% lack adequate access to food, and 20% of households have overcrowding, high housing costs, lack of kitchen facilities, or lack of plumbing facilities. The average life expectancy in the county is 73.2 years (by race/ethnicity: 85.9 among Asian Americans, 84.2 among Hispanic Americans, 72.6 among Black Americans, 72.6 among White Americans). Augusta-Richmond County is 57.5% Black/African American, 35.3% White, and 5.1% Hispanic/Latino (QuickFacts Augusta-Richmond County consolidated government, Georgia).

A semi-structured interview guide was developed by experienced qualitative researchers (LC, CJWL) in 2021. The guide centered on understanding the health of the neighborhood, particularly through the COVID-19 pandemic. Questions gathered information on health behaviors and interactions with the healthcare system. Minor changes to the guide were made in response to participant confusion or to clarify meaning.

Neighborhood residents were recruited through two local primary care clinics and events in neighborhoods surrounding the medical center. Researchers scheduled in-person interviews at a time and place convenient for residents. Consent for audio recording was obtained. Participants were interviewed from November 2021 to October 2022. Interviewees received a $25 gift card. Interviews ranged from 14 to 86 minutes, averaging 40 minutes. Once complete, a member of the research team documented participant’s pseudonym and uploaded the audio recording to an AU secure server. Episode profiles were created, outlining initial reactions and field notes to develop a holistic view of the interview. Files were transcribed, and identifiers were removed.

An experienced qualitative analyst (LC) analyzed transcript data using the Sort & Sift, Think & Shift method (Maietta, Mihas, Swartout, Petruzzelli, & Hamilton, Citation2021). Using this iterative process, each case was reviewed thoroughly using field notes, researcher reflections, and episode profiles. The analyst diagrammed each case to capture primary topics, dimensions, and properties. Next, researchers (LC, CJWL) took a step back to see connections and define relationships among the cases. Detailed memos kept data organized and ensured nothing was missed. Primary themes were established and arranged according to our research question. During analysis, we discussed how emerging themes fit within the attributes of place.

Of note, the primary analyst (LC) was not a Georgia resident, and the secondary analyst (CJWL) had lived in Augusta-Richmond County for less than 2 years at time of analysis. Throughout analysis, the analysts summarized findings and presented them to the CRANE steering committee, which includes lifelong local residents, academic researchers, and community clinicians, to discuss analysis and interpretation of data. Preliminary data analysis was also presented to two groups of local co-researchers (Shen et al., Citation2017) as a verification strategy.

Results

Thirty-one neighborhood residents completed interviews. presents sample characteristics.

Table 1. Sample characteristics (n = 31)

Threats to community trust were identified within four local-level attributes of place: availability of products and services, social structures, physical structures, and cultural and media messages.

Availability of Products and Services

Participants described how economic forces preceding and throughout the COVID pandemic negatively affected community health and threatened community trust.

Food Availability

Participants recognized economic forces that decreased food availability, which in turn threated community trust. A national grocery chain had closed its last store in downtown Augusta in 2017 (Cline, Citation2017). Although this was a national chain, residents described this as a local effect. The closure influenced not only resident health behavior but also how residents thought about the availability of healthy foods. An Augusta native described limited food options nearby, “[at convenience stores] you mainly get things like juices and milks … You can get things like eggs and bacon … but even then, it’s kind of limited the amount you can get with that. You can’t get any produce at all” (Participant (P) 24). Another resident shared, “there are a bunch of people who, instead of being able to use their EBT card at [grocery store] in walking distance, now they walk to the meat market, and they walk to four or five different church or outreach groups to get free food” (P9). Residents connect the lack of food availability to larger market forces. “…where the [grocery store] was torn down, now it’s just [medical school] parking. So, what the hell is that? More bullshit, so that somebody gets elected. I’m so jaded where there is politics” (P9). When patients saw (both literal and metaphorical) signs in their neighborhoods that a health system was limiting their ability to live a healthy life, their trust in the system decreased.

Many residents in this sample did not own or lease motorized vehicles. They described reliance on bicycles, relatives, ride sharing, and public transportation to access food and health care. One resident explained, “Catching the bus, it usually takes 4 hours or more. [And] it’s just a limited amount of stuff you can carry on the bus” (P16).

Healthcare Availability

Across the city’s health systems, residents described how limited access to quality, affordable healthcare impacted community trust.

Access

Residents described obstacles to scheduling appointments with primary care, mental health, and specialist care. Residents described living only miles away but without reliable transportation to access health care when they needed it. One resident observed,

The [medical] school is there, but the real world that I’m living in is far, far from them. The only way they can get help is to have a stroke or heart attack, or a mental breakdown. I think there should be care before it gets that bad, but it’s not available. They don’t have access to it. They can’t get to it because of transportation issues or lack of family supports. So it’s like living in a community that’s part of a third world country, but here we are in the middle of Augusta (P29).

COVID-19 amplified scheduling issues within the community. One resident said, “I had to wait a long time … when they lifted up the restriction with COVID, a lot of people are starting to see the doctors and appointments are thoroughly full” (P30).

Limited access threatened community trust particularly when residents connected inaccessibility to other factors such as insurance status. When one resident tried to make an appointment with a specialist, she encountered roadblocks, saying, “[The scheduler] said, ‘I’m sorry, there’s a scheduling problem.’ I said, ‘by scheduling problem, do you mean that you’re not seeing uninsured patients?’ and she nodded her head” (P32).

The complexity of accessing emergency services also threatened community trust. One resident described, “You have to call this [ambulance] first to ask their permission if they can go to that call. If they say no, that means you can’t go. So if I got Ambulance A, B, and C, if C says no, A and B can’t go … all these politics and red tape … I don’t have time for which ambulance company is going to come and get me … so if I got an ax in my shoulder, I’m gonna hold the ax and you drive” (P17).

Quality

Another threat to community trust was low-quality health care. Residents described how health systems did not treat them like people. Repeatedly, they described how health systems “discharge patients to the street” without regard for their living situation. One resident said, “Even when I was discharged, they wouldn’t even make sure that I got home safe. I ended up having to pay an Uber to get home. The social worker was supposed to take care of it … there was nobody. It was just me against the world. It was awful” (P29). Residents who experienced depersonalizing care lost trust in the system.

Residents also described how health care at a teaching institution affected their perceptions of quality. For some residents, accessing health care at a teaching hospital equated to well-trained clinicians. One resident explained, “I see a lot of those doctors and I know it’s a teaching college … they’ve been courteous enough to ask me if I mind a resident [physician]. They have to start somewhere. I also find it respectful … I’m all for it” (P30).

However, for some residents, inclusion of learners in patient care threatened trust. One resident shared, “I do not have anything against students being present during my care to learn, but when it’s a procedure … I don’t mind the student being present to learn, but I don’t want them doing the actual sticking. Yet I verbalized that and it still happened, and then I ended up having to spend two days in the hospital because they did not respect my rights” (P29). Another resident shared her friends’ uncertainty about student involvement, saying “they didn’t feel super confident that people knew what they were doing because the students, they didn’t know who was a student and who wasn’t and so do I want to go there cause it’s a bunch of students there” (P14). These residents did not describe these situations as individual-level clinician distrust but a broader distrust of the teaching institution.

Cost

Residents described how healthcare costs impact the community’s relationship with health systems. Unexpected bills and hospital collections negatively decreased their trust. “It’s always been in the back of my mind where if you go and see one physician, they refer to all their friends so everybody else can make some money … that’s why I feel like people in my community just don’t trust physicians” (P17). Multiple residents reported that medical bills had ruined their credit. When unpaid bills were sent to hospital collections, those actions directly reduced patient trust in the system. One resident reported, “I hate to say that money is what makes me decide [to get care]. I cannot afford to go to the doctor. That’s the first thing that comes up … [health system] would just tear my credit up, submitting the bill saying I don’t want to pay them” (P29).

Availability of Social Services and Programs

Residents described their reliance on social programs, such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, subsidized housing, and utility vouchers. One participant explicitly described how these services have an overall impact on health, saying, “People need help with their utilities. You can’t have good health if you’re always cold and you’re always hot … it affects their health too, and it affects their mental health as well as their physical well-being” (P32). Residents then described how COVID decreased the availability and their accessibility of social programs.

Accessing social services was complex, required computer access, and advanced digital literacy. While helpful for a time, residents recognized that social services created a leaky safety net that fills an immediate gap but does not build trust. One resident described it as being trapped, saying, “ … if you lose your resources or government support, now you have to pay for food and shelter and your transportation, when before you only had to pay for transportation and shelter, and not food, it makes a big difference. So, you’re kind of trapped in this horrible feedback loop where you want to go further, but it ends up setting you back … it’s very frustrating and political” (P11).

Social Structures

As part of a larger social system, residents described how negative experiences with police and city government decreased trust in the system.

Police presence was seen as a risk in some places, and in others as neglect. Some residents describe their neighborhoods as places where police do not patrol and are slow to respond. One resident explained, “You rarely will see a police officer … I have called at least four times [in the last 6 months] to Richmond County, reporting that I’ve seen them deal drugs outside my window. The response from them has been limited, delayed.” (P29). When police do take action, it appears to be racially motivated or targeted. One participant recounted, “I’ve watched too many black men get pulled over in my new road … I watched a black man get pulled over in my neighborhood and there were three squad cars with three white dudes, a Hispanic dude, and a black dude, and they made the Hispanic guy and the black guy harass this man for an hour and a half, and any little bit of faith I had is gone” (P9). She further described a conversation with her brother who has a black son, “my mom is over here, like ‘why don’t she and he trust the police?’ And I’m like ‘Momma, shut up, you’re going to get the child killed, please don’t do that’” (P9). Negative police encounters and threats to trust were described by both African American and White residents.

Residents described specific threats to community health, such as potholes, litter, overgrown vegetation that harbor snakes and rodents, and abandoned houses. When residents contacted the city government’s code enforcement office to address these concerns, they encountered delays and inaction. One resident explained, “The city, they don’t always come out and do repairs. If you call it in, they may not come.” (P26). This lack of city enforcement decreased community trust in local government.

Physical Structures

Physical structures in the neighborhoods also impacted community trust, particularly housing issues and the location of medical school buildings.

Historic residents described the effects of the reduction in subsidized housing stock and gentrification of neighborhoods. Some residents described changes as positive, resulting in safer neighborhoods. One resident recounted: “I grew up down in this area … I like to see new buildings and wider things and housing developments torn down that probably should have been because of the violence. They’re all a part of [medical school] now, so I see that it’s growing and the things that they’re doing with [neighborhood], and it looks good” (P2).

However, residents describe a general sense of mistrust when talking about the availability of housing and worry about future changes. One resident said, “it is gentrified … It’s making [long-time residents] upset. It’s taken their taxes up higher, real high. I watched four houses on my block change hands real fast … It was banks and mortgage companies and larger companies profiting off of a lot of misery” (P9). With gentrification, short-term rentals also affected the neighborhoods. One resident said, “an Air BnB, I had to call the police because it had gotten so bad that the music was so loud and they were just making a whole lot of noise, and I’ve even talked to the commissioner about it, but they say that they don’t have an ordinance for Air BnBs” (P33). As the neighborhoods experienced gentrification, rents rose. One resident felt hurt when her landlord tried to raise the price of rent saying, “the price of rent has just skyrocketed in this area … If I have to pay this amount, I’m going to have to make the decision whether I get health care, get my medication, or lights” (P29).

Residents also talked about what it was like to live near the medical school. One resident described how students consistently parked in front of his house but did not acknowledge him on his porch. He said, “They’ll park right in front of your house, get out and walk across the street, don’t say nothing to you. Their car might be there six or seven hours. They don’t say nothing. How are they supposed to be building a relationship with the community and your own people parked in my front yard and won’t say nothing?” (P12) When students ignored residents, it was a missed opportunity to build community trust.

Cultural and Media Messages

Residents described generational experience and historic knowledge of Tuskegee Syphilis Study and Henrietta Lacks as threats to community trust. One resident specified a generational mistrust, saying, “there is a lot of mistrust for the medical community in general among especially older black people because they lived at a time when there was a reason to mistrust. And I think that still exists, and it’s not great because these are the people who need it the most, black people. We have a lot of medical issues that need to be addressed” (P6). Another resident connected historical examples of abuse to mistrust, saying, “Most people are kind of skeptical [about research], especially African Americans, like they might give them something to harm them. It’s a trust issue … They don’t want to be used as an experiment like guinea pigs” (P23). The shared knowledge of these historic examples of abuse makes them more powerful than just individual knowledge.

When COVID emerged as a public health threat, it amplified already existing trust issues in the community. One resident summarized,

COVID really raised a lot of questions of what’s real and what’s not. It raised a lot of questions of who can I trust. When you tell a person that already has trust issues with police, you have trust issues with hospitals. People don’t go to the hospital because they don’t trust hospitals … now you’re adding another thing that they can’t trust in. They’re wondering, where did COVID come from? All these different questions, and then social media is ridiculous, so you got a million different opinions of what happened, so now it’s like, you got layers of distrust, and when you don’t trust nobody, what do you do? (P14)

Buffers to Trust Threats

Across the four attributes of place, residents expressed opportunities to build trust. One resident explained that health systems need to spend more time outside the clinic walls in the community. He said, “If [health system] can be more proactive, you’re inclined to have a return on your investment, which are the people – the patients. We understand the business part of it, but you have to invest in them. That’s where you build that trust … and knowledge” (P18).

When residents had trusting relationships with individual clinicians, it provided some protection from systemic trust threats. One resident described his relationship with his doctor, “If you’re honest up front, then I can trust you because I feel like you care. And my doc, I go back to him all the time because I believe that he’s going to let me know what I need to know” (P14). Another resident explained, “Cost is always an issue for me now, even with insurance … But I have open communication with my doctor, so if I ever need something, I could shoot an e-mail through the portal and we can go through that way and I won’t have to come in and there is no co-pay” (P19).

One resident shared his own blueprint for how to improve future communication with the community, emphasizing the long-term investment in relationships. “You may have multiple things you want to lay out over three and five years. You have to be very strategic about showing people that you can be trusted … They might not listen on the first and second, but they might listen on the third. If you just continue to be consistent, they’re gonna listen at some point” (P14). He continued to describe how honesty amidst uncertainty was key when talking about new treatments or vaccines. “ … so this is where honesty is key … know what they are up front. And if you tell people, they’ll be like, look, you told me, I knew what I was getting myself into. But if you don’t tell me and something happens, then I can’t trust you no more. Then you lose the trust and everything you built is gonna crumble” (P14). He summarized, “So I would say consistency, communication, and building a real foundation of relationship. Anybody can achieve that, it doesn’t matter what race you are” (P14).

Discussion

Our findings highlight the importance of examining trust at the community level, provide insight into an array of factors that impact trust at a local level, and extend the work on trust and its related constructs (e.g., mistrust) (see ). Participants expressed how what happens at the community level impacts how they view health and health recommendations. We found a broader web of services, policies, and institutions, beyond interactions with health care, that influence the trust placed in health officials and institutions. Participants spoke to both a potential lack of trust (e.g., needs not being met, as through lack of access to services) and mistrust (e.g., negative motives, such as profit seeking or experimentation) and distrust (i.e., beliefs about negative motives tied to specific incidents or interactions). Participants also provided recommendations on how to develop trust with community and local leaders.

Although the study design did not sample exclusively African American participants, findings echo previous studies of medical mistrust within the African American population. Mistrust (and distrust) of the medical system is not only a result of experiences inside the system but a reflection of inequities outside the medical system (e.g., policing, voting rights, immigration policies) (Williamson, Smith, & Bigman, Citation2019). Thus, our findings align with the work of scholars who posit that medical mistrust is impacted by any institutional processes, or broader social and economic exclusion, that create reminders of how communities are harmed, (Alang, McAlpine, & Hardeman, Citation2020) suggesting that similar factors can influence both trust and mistrust. (Jaiswal & Halkitis, Citation2019; Williamson, Smith, & Bigman, Citation2019). These findings also align with the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Framework, which outlines community and societal levels of influence within not only the healthcare system but also the domains of biological, behavioral, built environment, and sociocultural environment (NIMHD Research Framework, Citation2017). In all, the breadth of community factors reveals the chronic nature of not just medical mistrust but the adaptive response to chronic inequity in other systems, outside of healthcare, which create a lens through which public health and medical communication is perceived. For instance, participants discussed the impact of the larger social system, including police presence.

In 2020, a national racial justice movement developed in response to the death of George Floyd (Cokley et al., Citation2022). Data in our previous study suggested that this movement further eroded African American trust not only in White healthcare providers but entire systems (Ledford et al., Citation2022). In the wake of this movement, a 2021 commentary declared policing a public health issue (Fleming et al., Citation2021). Results here support this assertion by aligning with other studies suggesting that conditions outside the health system impact relationships with the health system (Alang, McAlpine, & Hardeman, Citation2020; Camp, Voigt, Jurafsky, & Eberhardt, Citation2021). Thus, considerations of health and medical recommendations must both take into account, and look beyond, the healthcare system. Within underserved communities, negative relationships with one governmental organization can influence how the community processes information communicated by a separate government sector. For instance, when residents of a neighborhood feel abandoned by the police, those negative feelings can affect how those residents respond to messages from public health officials. This has consequences not only for how precursors to trust and mistrust are viewed, but also for health policy.

Participants also expressed frustrations about access, quality, and cost of health care. Access encompassed inability to schedule primary care appointments and emergency services, suggesting attention must be paid to the larger health infrastructure to build trust with communities. Further, we found that poor quality healthcare interactions influence trust and mistrust. This aligns with previous work which called attention to the role of both personal (Hammond, Citation2010) and vicarious (Williamson, Citation2021) negative healthcare experiences. The impact of these experiences on trust and distrust may be amplified for individuals who live in the shadow of health systems but cannot gain access or are discriminated against. Health system neighbors are impacted by cultural and media messages. Our findings point to how these histories are passed from generation to generation throughout communities, underscoring a need to understand how trust is networked and communicated.

Our team previously observed that the intersectionality of place and race influence both health intentions/behaviors and outcomes among African Americans living in the American South (Moore et al., Citation2021; Moore et al., Citation2022). The lived experiences of food swamps (Brown et al., Citation2021), gentrification, lack of transportation, and financial strain (Coughlin, Moore, & Cortes, Citation2021) of healthcare utilization illuminated in the current investigation provide additional contextual evidence that place and race influence health through complex socio-political infrastructure and reduce African American patients’ trust in healthcare systems.

Multiple levels of factors influence medical mistrust (Williamson & Bigman, Citation2018). When applying these factors to COVID-19, it suggests that disease-specific beliefs, beliefs about medical institutions generally, beliefs about institutions more broadly, and societal beliefs feed into medical mistrust. This study suggests in thinking about levels of influence, space must be made for community-level factors as well. To date, quantitative work to model mistrust has not included these types of community-level factors (Hammond, Citation2010; Williamson, Citation2021). When neighborhood factors have been considered, they were confined to aspects like residential stability and crime rates (Shoff & Yang, Citation2012). We must consider how community is situated within the fabric of experiences and communication practices that impact trust.

One primary limitation of this study is the focus on place-based influences. Participants described people-based fields of influence; however, this inquiry worked to understand local-level community attributes. The place threats to community trust described here are likely present in similar neighborhoods throughout the country. However, the rich description in this study is limited to a specific geographic and cultural context. Another limitation is that this study aimed to describe place threats to community trust and was not designed to determine the strength of the relationships between place attributes and community trust. Future research should test the strength of these place effects. Other areas of inquiry should also test how interaction of attributes of people and places impact community trust and uptake of public health recommendations.

This study revealed opportunities for communication of public health initiatives in future pandemics and the need to build trust now. As communicators, we cannot ignore communities’ lived experiences, or idly watch as harmful policies are created (within or outside of health care), and expect communities to trust communication during a public health emergency. As participants noted, building trust requires transparency, engagement, and long-term investment. Transparency requires acknowledgment of the mistreatment of the community, failing to do so may increase mistrust (Williamson, Smith, & Bigman, Citation2019). Thus, understanding how best to communicate about this mistreatment is imperative and should be done through engagement with communities. These conversations can create open dialog and equitable spaces for community members to be present and heard as stakeholders (Dutta, Citation2018). Finally, long-term investment includes building relationships and demonstrating to communities that the healthcare institutions and their agents are invested in their well-being from the beginning, not just when things are dire. In Augusta, the University has already begun to form relationships that incorporate these elements. For instance, Augusta University Family Medicine supports a local free and charitable clinic that is forward facing in the community. Additionally, this project directly led to the creation of CRANE, which created a persistent infrastructure to enable the University to develop ongoing, collaborative relationships with community members. When a future crisis emerges, these existing relationships will enable community members to seek information and provide community insight while simultaneously enabling communication and public health professionals to disseminate information.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alejandra Garcia Rychtarikova, Hailie Hayes, Eunice Lee, and Courtney Roberts for their support in data collection; Amelia Vu and Faith Elliot for their support in community outreach events; Rev Dr Charles Goodman, Rev Isaiah Lineberry, and Corey Rogers for their wisdom, insight, and historical expertise in the development of this project; Kim Thompson and Zachary Cooper for their advocacy of the project in their clinical spaces; and Traci Greene, the coordinator of the Co-Researcher Activation Network (CRANE). We also thank all of our neighbors who shared their time and experiences with us through this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alang, S., McAlpine, D. D., & Hardeman, R. (2020). Police brutality and mistrust in medical institutions. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 7(4), 760–768. doi:10.1007/s40615-020-00706-w

- Armstrong, K., Rose, A., Peters, N., Long, J. A., McMurphy, S., & Shea, J. A. (2006). Distrust of the health care system and self-reported health in the United States. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(4), 292–297. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00396.x

- Benkert, R., Cuevas, A., Thompson, H. S., Dove-Meadows, E., & Knuckles, D. (2019). Ubiquitous yet unclear: A systematic review of medical mistrust. Behavioral Medicine, 45(2), 86–101. doi:10.1080/08964289.2019.1588220

- Blakely, R. L. & Harrington, J. M. (1997). Bones in the Basement: Postmortem Racism in Nineteenth Century Medical Training. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Bogart, L. M., Ojikutu, B. O., Tyagi, K., Klein, D. J., Mutchler, M. G., Dong, L. … Kellman, S. (2021). COVID-19 related medical mistrust, health impacts, and potential vaccine hesitancy among black Americans living with HIV. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 86(2), 200–207. doi:10.1097/qai.0000000000002570

- Brown, J. A., Ferdinands, A. R., Prowse, R., Reynard, D., Raine, K. D., & Nykiforuk, C. I. J. (2021). Seeing the food swamp for the weeds: Moving beyond food retail mix in evaluating young people’s food environments. SSM - Population Health, 14, 100803. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100803

- Calvillo, D. P., Ross, B. J., Garcia, R. J. B., Smelter, T. J., & Rutchick, A. M. (2020). Political ideology predicts perceptions of the threat of COVID-19 (and susceptibility to fake news about It). Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(8), 1119–1128. doi:10.1177/1948550620940539

- Camp, N. P., Voigt, R., Jurafsky, D., & Eberhardt, J. L. (2021). The thin blue waveform: Racial disparities in officer prosody undermine institutional trust in the police. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 121(6), 1157–1171. doi:10.1037/pspa0000270

- Carpenter, D. M., DeVellis, R. F., Hogan, S. L., Fisher, E. B., DeVellis, B. M., & Jordan, J. M. (2011). Use and perceived credibility of medication information sources for patients with a rare illness: Differences by gender. Journal of Health Communication, 16(6), 629–642. doi:10.1080/10810730.2011.551995

- Chan, H. Y. (2021). Reciprocal trust as an ethical response to the COVID-19pandemic. Asian Bioethics Review, 13(3), 1–20. doi:10.1007/s41649-021-00174-2

- Chandler, R., Guillaume, D., Parker, A. G., Mack, A., Hamilton, J., Dorsey, J., & Hernandez, N. D. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 among black women: Evaluating perspectives and sources of information. Ethnicity & Health, 26(1), 80–93. doi:10.1080/13557858.2020.1841120

- City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2021. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 5 from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-total-cities-and-towns.html

- Cline, D. (January 30, 2017). Kroger to close 15th Street store. The Augusta Chronicle. https://www.augustachronicle.com/story/business/2017/01/30/kroger-close-15th-street-store/14270207007

- Cohen, D. A., Scribner, R. A., & Farley, T. A. (2000). A structural model of health behavior: A pragmatic approach to explain and influence health behaviors at the population level. Preventive Medicine, 30(2), 146–154. doi:10.1006/pmed.1999.0609

- Cokley, K., Krueger, N., Cunningham, S. R., Burlew, K., Hall, S., Harris, K. … Coleman, C. (2022). The COVID-19/racial injustice syndemic and mental health among black Americans: The roles of general and race-related COVID worry, cultural mistrust, and perceived discrimination. Journal of Community Psychology, 50(6), 2542–2561. doi:10.1002/jcop.22747

- Coughlin, S. S., Moore, J. X., & Cortes, J. E. (2021). Addressing financial toxicity in oncology care. Journal of Hospital Management and Health Policy, 5, 32. doi:10.21037/jhmhp-20-68

- County Health Rankings and Roadmaps. (2022). University of wisconsin population health institute. Retrieved October 8 from www.countyhealthrankings.org

- De Meulenaer, S., De Pelsmacker, P., & Dens, N. (2018). Power distance, uncertainty avoidance, and the effects of source credibility on health risk message compliance. Health Communication, 33(3), 291–298. doi:10.1080/10410236.2016.1266573

- Dutta, M. J. (2018). Culture-centered approach in addressing health disaprities: Communication infrastructure for Subaltern voices. Communication Methods and Measures, 12(4), 239–259. doi:10.1080/19312458.2018.1453057

- Emmers-Sommer, T. M., & Terán, L. (2020). The “Angelina Effect” and audience response to celebrity vs. Medical expert health messages: an examination of source credibility, message elaboration, and behavioral intentions. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 17(1), 149–161. doi:10.1007/s13178-019-0375-z

- Fleming, P. J., Lopez, W. D., Spolum, M., Anderson, R. E., Reyes, A. G., & Schulz, A. J. (2021). Policing is a public health issue: The important role of health educators. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 48(5), 553–558. doi:10.1177/10901981211001010

- Freed, G. L., Clark, S. J., Butchart, A. T., Singer, D. C., & Davis, M. M. (2011). Sources and perceived credibility of vaccine-safety information for parents. Pediatrics, 127 Suppl 1(Supplement_1), S107–112. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1722P

- Gram‐hanssen, K., & Bech‐danielsen, C. (2004). House, home and identity from a consumption perspective. Housing, Theory and Society, 21(1), 17–26. doi:10.1080/14036090410025816

- Griffith, D. M., Bergner, E. M., Fair, A. S., & Wilkins, C. H. (2021). Using mistrust, distrust, and low trust precisely in medical care and medical research advances health equity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 60(3), 442–445. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2020.08.019

- Grimes, D. R. (2021). Medical disinformation and the unviable nature of COVID-19 conspiracy theories. Plos One, 16(3), e0245900. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0245900

- Hammond, W. P. (2010). Psychosocial correlates of medical mistrust among African American men. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45(1–2), 87–106. doi:10.1007/s10464-009-9280-6

- Hesse, B. W., Nelson, D. E., Kreps, G. L., Croyle, R. T., Arora, N. K., Rimer, B. K., & Viswanath, K. (2005). Trust and sources of health information: The impact of the internet and its implications for health care providers: Findings from the first health information national trends survey. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165(22), 2618–2624. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.22.2618

- Iyasere, J., Garcia, A., Prabhu, D. V., Procaccino, A., Spaziani, K. J., Smith, L., & Berchuck, C. M. (2021). A community partnership to house and care for complex patients with unstable housing. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery, 2(8). doi:10.1056/cat.21.0158

- Jaiswal, J., & Halkitis, P. N. (2019). Towards a more inclusive and dynamic understanding of medical mistrust informed by science. Behavioral Medicine, 45(2), 79–85. doi:10.1080/08964289.2019.1619511

- Ledford. (2021). Cultivating community co-researchers to build capacity for PCOR for COVID-19. Grant.

- Ledford, C. J. W., Cafferty, L. A., Moore, J. X., Roberts, C., Whisenant, E. B., & Garcia Rychtarikova, A.… (2022). The dynamics of trust and communication in COVID-19 vaccine decision making: A qualitative inquiry. Journal of Health Communication, 27(1), 17–26. doi:10.1080/10810730.2022.2028943

- Maibach, E. W., Abroms, L. C., & Marosits, M. (2007). Communication and marketing as tools to cultivate the public’s health: A proposed “people and places” framework. BMC Public Health, 7(1), 15–88. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-88

- Maietta, R., Mihas, P., Swartout, K., Petruzzelli, J., & Hamilton, A. B. (2021). Sort and sift, think and shift: Let the data be your guide an applied approach to working with, learning from, and privileging qualitative data. Qualitative Report, 26(6). doi:10.46743/2160-3715/2021.5013

- Ma, Z., & Ma, R. (2021). Predicting intentions to vaccinate against COVID-19 and Seasonal Flu: The role of consideration of future and immediate consequences. Health Communication, 37(8), 1–10. doi:10.1080/10410236.2021.1877913

- Moore, J. X., Gilbert, K. L., Lively, K. L., Laurent, C., Chawla, R., & Li, C.… (2021). Correlates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among a community sample of African Americans lIving in the Southern United States. Vaccines, 9(8), 879. doi:10.3390/vaccines9080879

- Moore, J. X., Tingen, M. S., Coughlin, S. S., O’meara, C., Odhiambo, L., Vernon, M. , … Cortes, J. (2022). Understanding geographic and racial/ethnic disparities in mortality from four major cancers in the state of Georgia: A spatial epidemiologic analysis, 1999–2019. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 14143. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-18374-7

- Nguyen, K. H., Nguyen, K., Corlin, L., Allen, J. D., & Chung, M. (2021). Changes in COVID-19 vaccination receipt and intention to vaccinate by socioeconomic characteristics and geographic area, United States, January 6 – March 29, 2021. Annals of Medicine, 53(1), January 6 - January 6, 2021, 1419–1428. doi:10.1080/07853890.2021.1957998.

- NIMHD Research Framework. (2017). https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/overview/research-framework/nimhd-framework.html

- Palmedo, P. C., Rauh, L., Lathan, H. S., & Ratzan, S. C. (2022). Exploring distrust in the wait and see: Lessons for vaccine communication. The American Behavioral Scientist, 00027642211062865. doi:10.1177/00027642211062865

- Park, H., & Lee, T. D. (2018). Adoption of E-Government applications for public health risk communication: Government trust And social media competence as primary drivers. Journal of Health Communication, 23(8), 712–723. doi:10.1080/10810730.2018.1511013

- Peek, M. E., Gorawara-Bhat, R., Quinn, M. T., Odoms-Young, A., Wilson, S. C., & Chin, M. H. (2013). Patient trust in physicians and shared decision-making among African-Americans with diabetes. Health Communication, 28(6), 616–623. doi:10.1080/10410236.2012.710873

- Peng, J., Strijker, D., & Wu, Q. (2020). Place identity: How far have we come in exploring its meanings? [Review]. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00294

- QuickFacts Augusta-Richmond County consolidated government, Georgia. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 5 from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/augustarichmondcountyconsolidatedgovernmentbalancegeorgia

- Ruiz, J. B., & Bell, R. A. (2021). Predictors of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Results of a nationwide survey. Vaccine, 39(7), 1080–1086. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.01.010

- Shen, S., Doyle-Thomas, K. A. R., Beesley, L., Karmali, A., Williams, L., Tanel, N., & McPherson, A. C. (2017). How and why should we engage parents as co-researchers in health research? A scoping review of current practices. Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 20(4), 543–554. doi:10.1111/hex.12490

- Shoff, C., & Yang, T. -C. (2012). Untangling the associations among distrust, race, and neighborhood social environment: A social disorganization perspective. Social Science & Medicine, 74(9), 1342–1352. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.012

- Trachtenberg, F., Dugan, E., & Hall, M. A. (2005). How patients’ trust relates to their involvement in medical care. The Journal of Family Practice, 54(4), 344–352.

- Wilk, A. S., & Platt, J. E. (2016). Measuring physicians’ trust: A scoping review with implications for public policy. Social Science & Medicine, 165, 75–81. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.07.039

- Williamson, L. D. (2021). Testing vicarious experiences as antecedents of medical mistrust: A Survey of black and white Americans. Behavioral Medicine, 49(1), 1–13. doi:10.1080/08964289.2021.1958740

- Williamson, L. D., & Bigman, C. A. (2018). A systematic review of medical mistrust measures. Patient Education and Counseling, 101(10), 1786–1794. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2018.05.007

- Williamson, L. D., Smith, M. A., & Bigman, C. A. (2019). Does discrimination breed mistrust? Examining the role of mediated and non-mediated discrimination experiences in medical mistrust. Journal of Health Communication, 24(10), 791–799. doi:10.1080/10810730.2019.1669742

- Xu, P., & Cheng, J. (2021). Individual differences in social distancing and mask-wearing in the pandemic of COVID-19: The role of need for cognition, self-control and risk attitude. Personality and Individual Differences, 175, 110706. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2021.110706

- Yang, Q., Chen, Y., & Wendorf Muhamad, J. (2017). Social Support, trust in health information, and health information-seeking behaviors (HISBS): a study using the 2012 annenberg national health communication survey (ANHCS). Health Communication, 32(9), 1142–1150. doi:10.1080/10410236.2016.1214220