Abstract

COVID-19 vaccination has resulted in decreased hospitalization and mortality, particularly among those who have received a booster. As new effective pharmaceutical treatments are now available and requirements for non-pharmaceutical interventions (e.g. masking) are relaxed, perceptions of the risk and health consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection have decreased, risking potential resurgence. This June 2022 cross-sectional comparative study of representative samples in New York City (NYC, n = 2500) and the United States (US, n = 1000) aimed to assess differences in reported vaccine acceptance as well as attitudes toward vaccination mandates and new COVID-19 information and treatments. NYC respondents reported higher COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and support for vaccine mandate than U.S. respondents, yet lower acceptance for the booster dose. Nearly one-third of both NYC and U.S. respondents reported paying less attention to COVID-19 vaccine information than a year earlier, suggesting health communicators may need innovation and creativity to reach those with waning attention to COVID-19-related information.

As the first epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States (US) in early 2020, New York City (NYC) had especially high rates of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and deaths (NYC Health, Citationn.d.). Existing racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities exacerbated initial viral transmission and hindered response efforts, driving greater COVID-19 morbidity and mortality among these communities (De Jesus et al., Citation2021; El-Mohandes et al., Citation2020; Huang & Li, Citation2022; Kim et al., Citation2021; Lieberman-Cribbin, Tuminello, Flores, & Taioli, Citation2020). New Yorkers also experienced disruptive impacts such as food insecurity (Clay & Rogus, Citation2021), delay or disruption in education and health-care access (Bakouny et al., Citation2022; Talmor et al., Citation2022), and psychosocial and mental health effects (Feingold et al., Citation2021; Jones, Manze, Ngo, Lamberson, & Freudenberg, Citation2021; Lopez-Castro et al., Citation2021). This severity of the outbreak, unequaled in any other parts of the US at that time may have impacted the population of the city in unique ways vis-a-vis their views on the dangers associated with the virus and its effect on their daily lives, as well as the importance of finding ways to protect themselves once available.

Now, well into the fourth year of the pandemic, no part of the world has been untouched. However, the severity and persistence of the disease has varied considerably across countries and within countries (Rostami et al., Citation2021). COVID-19 vaccines have offered robust protection against the disease, notably against severe infection, hospitalization, and death (Burki, Citation2022; Celardo, Pace, Cifaldi, Gaudio, & Barnaba, Citation2020; Shi et al., Citation2020). Throughout the pandemic, researchers aimed to assess public willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine (Latkin et al., Citation2021; Lazarus et al., Citation2020; Lazić & Žeželj, Citation2021; Mondal et al., Citation2021; Trent, et al., Citation2022; Shekhar et al., Citation2021; Solis Arce et al., Citation2021). Subsequently, following widespread distribution of the vaccines beginning in early 2021, the research focus shifted to assessments of public attitudes, uptake, and reasons for acceptance or continued reluctance or refusal (Batra, Sharma, Dai, & Khubchandani, Citation2022; de Figueiredo & Larson, Citation2021; El-Mohandes et al., Citation2021; Palmedo et al., Citation2022; Roy, Biswas, Islam, & Azam, Citation2022).

In the US, COVID-19 vaccine acceptance has consistently correlated with age, education, income, and ideological/political party affiliation, as has adherence to other mitigation measures, such as wearing a face mask (El-Mohandes et al., Citation2021; Kirzinger et al., Citation2021; Sparks et. al., Citation2021). Differences in acceptance by race have shifted since the beginning of the pandemic, when no differences were observed, to March–June 2021, when black Americans began indicating higher intentions to vaccinate (Padamsee et al., Citation2022). Individual perceptions of the pandemic being less serious than generally portrayed were associated with a diminished belief that vaccination was necessary to protect against COVID-19 infection, and reduced willingness to get vaccinated or boosted (Lazarus et al., Citation2022). In addition, these attitudes were similarly associated with unwillingness to accept vaccine requirements or mandates by government, employers, schools and universities (Lazarus et al., Citation2022).

In this June 2022 study, we aimed to compare COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy across representative samples of adults in NYC to those of adults in the US overall. We also reported these comparisons by demographic strata. This study took place at a time when pandemic restrictions in the US were largely lifted, and voluntary public adoption of mitigation measures had simultaneously dropped significantly across the population. A few restrictions, such as requiring masking on public transportation and employee vaccine mandates, remained in effect in NYC during this time. The study also aimed to examine attitudes toward vaccination mandates, new COVID-19 information, and pharmaceutical treatments, overall and by vaccination status to determine whether previously observed distinctions between the vaccinated and unvaccinated (El-Mohandes et al., Citation2021; Lazarus et al., Citation2020; Teasdale et al., Citation2022) continue to be significant.

Methods

Study Design and Data Collection

An online opt-in panel of potential participants was provided by Consensus Strategies with participants being recruited by telephone contact, social media outreach and direct mail solicitation. The online platforms were available in English and Spanish. Stratum based on age, gender, statistical regions, and levels of education were created and a minimum of 50 participants was set for each stratum, with target enrollment calculated to reflect the distribution of each subgroup in the general population (US Census Bureau, Citation2020). All final strata included a minimum of 75 participants. Rake weights were utilized using the stratified panels in order to reflect the populations at study. Details on variable coding and weighting for strata, and participant recruitment methods are described elsewhere (Lazarus et al., Citation2020). Survey data were collected between 29 June and 10 July 2022 from respondents aged >18 years from NYC (n = 2,500) and the US (n = 1,000). The sample size was increased for NYC to allow for analysis of the five boroughs individually, and then these data were combined for city-wide analyses. The precision of online polls, measured using a credibility interval, was plus or minus 2.3% points for the overall NYC panel and plus or minus 3.5% points for the national sample. This study was approved, and the survey administered by Emerson College, Boston, USA (institutional review board protocol no. 20–023-F-E-6/12-[R1] updated April 12, 2021). No personally identifiable information was collected or stored.

Survey Instrument

The instrument was developed by an expert panel following a comprehensive literature review of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy literature, as described in earlier studies (Lazarus et al., Citation2020). The instrument (Supplemental Material 1) included questions regarding:

perceptions of COVID-19 risk, efficacy, safety, and trust;

vaccine acceptance or hesitancy, defined according to the WHO SAGE description (MacDonald, et al., 2015), and coded based on Likert responses to questions regarding receipt of). Vaccine acceptance was defined as having received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine and if not, willingness to take the COVID-19 vaccine when it is available to respondents. Vaccine hesitancy was defined as having reported “no” to the question on whether they have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine and also either unsure/no opinion, somewhat disagree, or strongly disagree to the question on whether they would take a COVID-19 vaccine when available to them. Vaccine acceptance and hesitancy for children was coded for respondents with children under 18;

booster vaccine dose acceptance and hesitancy, defined as having received at least one dose of a booster and if not, willingness to take the booster when it is available to respondents. Booster hesitancy among vaccinated was defined as having reported “no” to the question on whether they have received at least one booster dose and also either unsure/no opinion, somewhat disagree, or strongly disagree to the question on whether they would take a booster when available to them;

pharmaceutical medication use when sick with COVID-19 within the past year. Pharmaceutical medications include Paxlovid, Molnupiravir (lagevrio), monoclonal antibodies (olumiant/baricitinib), Ivermectin, corticosteroids;

support for six types of COVID-19 vaccine mandates: (a) employer-required (b) government-required, (c) to attend college/university, (d) to attend K-12 schools, (e) to attend indoor activities, such as conferences, concerts, or sports events, and (f) to travel internationally;

(a) level of attention paid to new information about COVID-19 vaccines compared to a year ago; (b) belief about vaccination protection against Long-COVID; (c) intent to vaccinate in light of perceived disease severity; and (d) preference for illness prevention through vaccination and/or treatment with medications post-infection;

COVID-19 experience (whether oneself or a family member became ill with COVID-19 within the past year or more than a year ago); and

socio-demographic variables (age, gender, race/ethnicity, and education).

Data Analysis

We used multivariable weighted logistic regressions to compare NYC with the US regarding acceptance of and hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccines, boosters, and child vaccination. Likewise, we compared the data from NYC to the overall US respondents in terms of their attitudes toward vaccination mandates and COVID-19 vaccine perceptions of risk, trust, safety, equity, and efficacy. Finally, we compared the data from NYC to the US respondents regarding the level of attention they are giving to new information about COVID-19 vaccines, COVID-19 treatment preferences, beliefs about effectiveness of vaccination for prevention of disease severity and protection against Long-COVID. Multivariable weighted logistic regression models were adjusted for age, gender, education, race/ethnicity. Finally, to further assess differences by demographic groups, we report NYC vs. the US comparisons stratified by age groups, gender, education, and race/ethnicity. Findings are reported as adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4.

Results

Respondent Characteristics, COVID-19 Experience and Treatment

Demographic characteristics of NYC and the US respondents are reported in . COVID-19 illness (oneself or one’s family member) within the past year was reported by three in seven of respondents in NYC (44.9%) and the US (44.1%). Nearly a fifth of NYC respondents (18.9%) and a fourth of US respondents (23.2%) received treatment with pharmaceuticals when diagnosed with COVID-19 ().

Table 1. Sample characteristics, COVID-19 experience and treatment with pharmaceutical medications

COVID-19 Vaccine and Booster Acceptance and Hesitancy

Reported vaccine acceptance was significantly higher in NYC than in the US (88.4% vs. 80.2%, aOR=.51, 95% CI (.39, .66). Among vaccinated respondents, receipt of at least one booster dose was reported by 55.5% of NYC respondents and 51.3% of the US respondents. However, booster hesitancy among those vaccinated was significantly higher in NYC than in the US (19.7% vs. 13%, aOR = 1.50, 95% CI (1.12, 1.99) ().

Table 2. COVID-19 vaccine and booster acceptance and hesitancy

Vaccine hesitancy was significantly lower in NYC compared to the US in the following demographic strata: respondents ages 18–29, 30–39, 40–49, men, women, respondents with and without a university degree and those self-identified as white. Booster hesitancy was significantly higher in NYC compared to the US in the following demographic strata: respondents ages 18–29, men and those with and without university degree (Supplementary Table S1. Vaccine and booster hesitancy by demographic characteristics).

COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy for Children

Reported COVID-19 vaccine acceptance for children was significantly higher among NYC parents than the US parents (73.4% vs. 66.9%, aOR=.71, 95% CI (.53, .96). Receipt of vaccine for children was reported by 59.5% of NYC parents and 52.5% of the US parents. Vaccine hesitancy among children whose parents were themselves hesitant was 80.2% in NYC and 90.3% in the US, however this difference was not statistically significant ().

Table 3. COVID-19 vaccine for children acceptance and hesitancy

Vaccine hesitancy for children was significantly lower in NYC compared to the US for children in the following demographic strata: parents were aged 30–39, parents without university degrees and parents self-identifying as white (Supplementary Table S1).

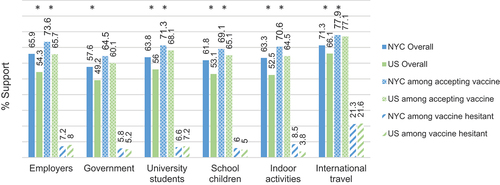

Support for COVID-19 Vaccination Mandates

Support for each type of vaccination mandate in this study was significantly higher among NYC compared to the US respondents (p < .05). Overall, support was lowest for widespread government mandates (NYC 57.6% vs. US 49.2%, aOR = 1.40, 95% CI (1.17, 1.69)) and highest for the specific proof of vaccination for international travel (NYC 71.3% vs US 66.1%, aOR = 1.35, 95% CI (1.11, 1.64)). Support for the international travel mandate was reported by 1 in 5 respondents who were hesitant to get vaccinated in both NYC and the US (NYC 21.3% vs. US 21.6%, aOR=.88, 95% CI (.35, 2.20)) (). Women in the NYC sample reported greater support for each of the five vaccination mandates studied as compared to their US counterparts; there was no significant difference among men between the samples (Supplementary Table S2). Similarly, white respondents in NYC reported greater support for vaccination mandates than their US counterparts, whereas no significant difference was found among other reported races between the samples (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 1. Support for COVID-19 vaccination mandates overall and by vaccine acceptance/hesitancy.

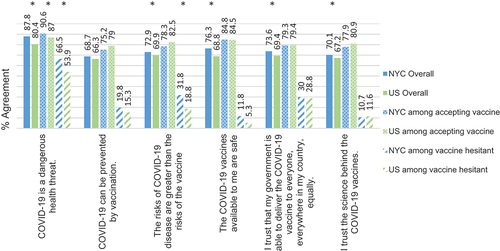

COVID-19 Vaccine Perceptions of Risk, Trust, Safety, Equity, and Efficacy

There was no significant difference in agreement by NYC and US respondents with the following statement about COVID-19 vaccine efficacy, “COVID-19 can be prevented by vaccination” (NYC 68.7% vs. US 66.3%, aOR = 1.12 95% CI (0.92, 1.35)). Agreement with all other statements about COVID-19 vaccine risk, trust, safety, and equity was significantly higher among NYC compared to the US respondents (p < .05) (). When comparing sub-samples of vaccine accepting and hesitant respondents, NYC respondents were significantly more likely than US respondents to agree that COVID-19 is a dangerous health threat, regardless of their vaccination status. Among respondents who accepted vaccination, agreement with all other statements was similar. Among the vaccine hesitant, NYC respondents were significantly more likely than US respondents to agree that the risks of COVID-19 disease are greater than the risks of the vaccine. Agreement with statements about risk, trust, safety, equity, and efficacy varied demographically between the two samples. For example, those aged 50+ years in NYC demonstrate a stronger agreement that COVID-19 is dangerous (aORs = 1.93 95% CI (1.13–3.20) and 3.46 95% CI (2.17–5.49)) and that the government can equitably deliver vaccines (aORs 1.57 95% CI (1.02–2.42) and 1.99 95% CI (1.36–2.91)) than their US counterparts (Supplementary Table S3).

Figure 2. Agreement with statement about risk, trust, safety, equity, and efficacy overall and by vaccine acceptance/hesitancy.

Attention to New Information About COVID-19 Vaccines, Beliefs About Vaccination Protection Against Long-COVID, Current Vaccination Intent and COVID-19 Treatment Preference

Nearly a third of NYC and US respondents reported that they now pay less attention to new information about COVID-19 vaccines than a year ago (NYC 27.7% vs. US 29.1%, aOR=.96, 95% CI (.78, 1.17). Similar proportions of NYC and US respondents believed that the vaccines can protect people from Long-COVID (NYC 48.9% vs. US 48.3% aOR = 1.06 95% CI(.88, 1.28). Intent not to vaccinate due to lower perceived disease severity was also similar (NYC 20.3% vs. US 23.1%, aOR=.91 95% CI (.72, 1.15)). Preference for neither vaccinating nor taking medication for treatment of COVID-19 was low overall but significantly lower among NYC compared to US respondents (6.3% vs. 13.5%, aOR=.47, 95% CI (.34, .65)) ().

Table 4. Attention to new information about COVID-19 vaccines, beliefs about vaccination protection against long-COVID, current vaccination intent and COVID-19 treatment preference

These variables are reported by demographic characteristics in Supplementary Table S4. Of note, paying less attention to new information about COVID-19 vaccines was reported significantly more frequently in the US compared to NYC among respondents 60+ years old. The belief that the vaccines can protect people from long-COVIDs was significantly less prevalent in NYC compared to the US among respondents with a university degree and those who identified themselves as black. Likelihood not to vaccinate due to perceived low disease severity was similar in NYC and the US in all demographic strata. Finally, preference not to take a vaccine or medication for COVID-19 was significantly higher in the US compared to NYC across all demographic strata.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine whether New Yorkers, who had arguably endured a more harsh and devastating early experience with COVID-19 than other Americans, may continue to report, even in the face of widespread “post-pandemic fatigue” (World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe, Citation2020), greater vaccine acceptance of suggested or mandated requirements than their peers nationally. The intense early exposure to COVID-19 that occurred in NYC, at a time when little was known about managing the spread and treatment of this disease, resulted in higher morbidity and mortality in NYC than was observed elsewhere in the US (NYC Health, 2022). This may contribute to why our findings suggest that New Yorkers, when compared to other US respondents, continue to report a greater risk perception of COVID-19, a lower perception of the risk associated with available vaccines and a higher level of vaccine acceptance, continuing trends observed since 2021 by our research group (El-Mohandes et al., Citation2021).

Greater vaccine acceptance in both the NYC and US populations was associated with individuals reporting personal experience with COVID-19. Conversely, although they are at the greatest risk for COVID-19 transmission, the unvaccinated remain least likely to vaccinate in the future, which may stem from their relatively lower perception of disease severity and relatively higher perception of complications from the vaccine. These factors, coupled with the gradual relaxation of required mitigation measures, and the availability of more effective FDA approved treatments for the disease itself, may reduce willingness to vaccinate or to accept boosters. It is unclear, given the timing of this analysis, what impact the new bivalent booster, covering omicron and subvariants of omicron SARS-CoV2, will have on booster uptake given estimated improvements in preventing acquisition and transmission of the virus.

Our results also show that acceptance of vaccine mandates remains significantly higher in NYC than in the US generally, particularly among those already vaccinated. As expected, this support is strongest among those who accept vaccination and much lower among the vaccine hesitant. The vaccine and masking mandates adopted were not authorized, enforced, or accepted uniformly across the country, and recent analyses of these mandates on COVID-19 outcomes suggest significant impact in reducing burden of disease (Greene et al., Citation2022). The current higher acceptance of mandates could also be explained by the community-level trauma experienced during the early outbreak in NYC, given higher COVID-19 risk perceptions in this sample, and the politically or ideologically liberal leanings of the City when compared to national averages.

The observed support for proof-of-vaccination requirements in NYC were perceived by some as an acceptable regulation of individual freedom that accorded greater personal freedom of access to the majority who accepted vaccination (Cohn, Chimowitz, Long, Varma, & Chokshi, Citation2022). Vaccination requirements effected a surge in COVID-19 vaccine uptake in NYC (Cohn, Chimowitz, Long, Varma, & Chokshi, Citation2022) and Europe (Karaivanov, Kim, Lu, & Shigeoka, Citation2022). As use of this important public health tool to drive vaccine uptake faces significant legal challenges to future use, it is likely that further acceptance of vaccinations and boosters will be impacted negatively (Gostin, Citation2021).

It is also critical to view the imposition of mandates in the context of generalized, population-wide risk of illness, severity of illness, and death, which at the time of their adoption, remained significant. This population-wide risk has diminished, in large part due to high levels of immunity conferred by vaccination, as well as significant numbers of infections, which has in turn, reduced the burden of severe illness and death, and thereby reduced the overall perception of risk in much of the population. This, combined with the fact that nearly 80% of New Yorkers of all ages have completed their primary series, and 89% of adults have received at least one dose of the vaccine, impacts the view of ongoing mandates to maintain population-wide protection.

Moreover, as ideological divides grow deeper, more polarized, regionalized, and politicized across the US, vaccine acceptance has been, and likely will continue to be, impacted by these trends (Batra, Sharma, Dai, & Khubchandani, Citation2022). While only a small minority of those unvaccinated for COVID-19 may be “anti-vaccine,” there is increasing evidence that this small but vocal opposition will continue to advocate forcefully for the refusal of both routine and novel vaccines in the future. Persistent unwillingness to vaccinate is a distinctive characteristic that may be rooted in a specific domain within an individual’s belief systems (Kirzinger, Sparks, & Brodie, Citation2021). The domain of personal autonomy and validity with respect to medical interventions is often reported by vaccine-hesitant and anti-mandate voices (Cohn, Chimowitz, Long, Varma, & Chokshi, Citation2022), though it is notably separate from the health domain itself (MacDonald & SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy, Citation2015). As such divides deepen, future pandemic response efforts may meet new challenges in health communication, sharing online and offline media spaces with anti-public health voices (Purnat, Wilson, Nguyen, & Briand, Citation2021).

As part of its key recommendations, a global multidisciplinary panel of COVID-19 experts encouraged a vaccines-plus approach to disease control that includes a range of public health and financial support measures. It recommends that among such measures, “Governments should only consider imposing broad restrictions on civil liberties in the event of variants of concern presenting risk of high rates of transmission and severity, coupled with (i) waning immunity or (ii) vaccine resistance” (Lazarus et al., Citation2022). Higher general vaccine acceptance in NYC did not translate to higher vaccine acceptance for children, which was the same in NYC compared to the US. Evidence of the overall disease severity being lower in children (Dorabawila et al., Citation2022), concerns about dosing and efficacy of the vaccine in ages 5–11 in terms of disease transmission, could have diminished the enthusiasm of parents to vaccinate their children, especially those of the younger age group (Teasdale et al., Citation2022, Citation2022). Also surprising was the finding that acceptance of boosters among New Yorkers who have accepted the vaccine was lower than that reported by US respondents. As both childhood vaccines and boosters were approved at a later stage in the COVID-19 pandemic, these specific declines in acceptance among New Yorkers could be associated with a general sense of “COVID-19 fatigue,” a desire to return to “normalcy,” and the gradual decline in implementing public health measures and recommendations. Throughout the US, people are experiencing information fatigue, and compliance with public health prevention measures is waning (Li, Haynes, Kulkarni, & Siddique, Citation2022); New Yorkers may still bear harsher memories of the first wave of COVID-19 but are not immune to the emerging COVID fatigue phenomenon. For boosters, this decline in acceptance may also reflect a perception of reduced impact in preventing infection, despite effectiveness in preventing severe illness, death, and Long-COVID syndrome. At the time of this study, the updated bivalent booster was not yet available and could represent an opportunity to improve vaccine confidence. It is worth noting that recent national modeling suggested that high booster uptake could prevent more 25,893,278 infections; 936,706 hospitalizations; and 89,465 deaths (Fitzpatrick at al., Citation2022)

These data hold several important implications for health communicators (Lazić & Žeželj, Citation2021). We found that nearly one-third of respondents in both NYC and the US samples reported paying less attention to information about COVID-19 vaccines than they did in the previous year. There is little variation between sociodemographic profiles, with an important exception that older adults (60+) in the US sample were most likely to report paying less attention. While the threat of serious illness and death from COVID-19 has decreased, this age group remains the most vulnerable and should be on the alert for any new health messaging that could be vital to their safety. If new variants emerge, effective communication of increased risk and the promotion of vaccination against newly emerging variants and other protective measures to this key population may prove increasingly challenging. These findings resonate with a 2020 survey, which included NYC residents, and demonstrated an association between in attention to COVID-19 information and hesitancy toward a potential vaccine (Bass et al., Citation2021). This is a critical issue to consider as increasingly more voices declare that the pandemic already behind us (BMJ, Citation2022).

Among the most trusted, and therefore potentially most effective, vaccination communicators remain health-care providers (Hamel et al., Citation2021). In the US, aspects of the clinical environment, such as short appointment times, often minimize the ability of providers to effectively counsel patients (Wittenberg, Goldsmith, Chen, Prince-Paul, & Johnson, Citation2021). In addition, health professionals increasingly find themselves competing with contradictory or conflicting alternative sources of health information. Patients receive information and advice from a variety of sources – internet and social platforms, local and national elected officials, media, and social networks – which can stand to reinforce or weaken science-backed recommendations (Pertwee, Simas, & Larson, Citation2022). These factors together coupled with the public’s COVID fatigue threaten to derail successful containment and mitigation efforts (Levine, Citation2022).

With the drawdown of federal emergency support for vaccination efforts, more burden will be shouldered by and local health departments and health-care delivery systems to facilitate and support COVID-19 vaccination by primary care providers, community health-care centers, and hospital systems, including providing appropriate tools for effective communication and messaging (Wilhite et al., Citation2022). Future vaccination efforts should consider targeting differentiated communication among vaccine accepting, under- or unvaccinated, and hesitant groups. Communicating through culturally competent, trauma-informed messaging and in collaboration with trusted community partners with shared experiences of COVID-19 may improve first-dose and booster-dose efforts within these communities.

Conclusion

Our study further confirms previous findings that New Yorkers, who were severely impacted early by the pandemic, remain more likely to get vaccinated against COVID-19 and to accept various mandates aimed at preventing its spread when compared to the rest of the US population. It is worth noting that New Yorkers are lagging in their acceptance of boosters, and in childhood vaccination. They also suffer to the same degree as the rest of the nation from “COVID fatigue,” which has dulled many Americans’ willingness to pay attention to new information about the disease, vaccinate their children, accept boosters themselves, or address the plight of the substantial number of individuals who remain symptomatic with Long-COVID. These findings emphasize the importance of maintaining high-level engagement with the NYC resident populations and not to rest on the previous success. Focusing on attaining higher booster levels, especially among the most vulnerable, and revitalizing communication strategies and vehicles will be essential to sustained acceptance of proven prevention interventions.

Strengths

This is the only study that presents data on population attitudes in NYC with accurate comparison to the prevailing national attitudes using a population-based survey methodology both in the city and nationally. It can reflect on credible differences and associate them with demographic and pandemic related variables. Our study is further strengthened by using the same methods and question items to previously published literature to which we draw comparisons (El-Mohandes et al., Citation2021; Lazarus et al., Citation2022; Teasdale et al., Citation2022).

Limitations

Some of the statistics reported in this study may vary slightly from those reported by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Such variation could be attributed to differences in the method of data collection or exact dates of data collection. The data comparability in this study between NYC and the US remains valid since the data was collected simultaneously and using the same methodology. Limitations exist in the comparison of vaccine mandate responses between the NYC and US samples owing to heterogeneity in the stringency and breadth of these policies in the US sample, factors we did not capture in our dataset.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bakouny, Z., Labaki, C., Bhalla, S., Schmidt, A. L., Steinharter, J. A., Cocco, J. … Doroshow, D. B. (2022). Oncology clinical trial disruption during the COVID-19 pandemic: A COVID-19 and cancer outcomes study. Annals of Oncology: Official Journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology, 33(8), 836–844. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2022.04.071

- Bass, S. B., Wilson-Genderson, M., Garcia, D. T., Akinkugbe, A. A., … Mosavel, M. (2021). SARS-CoV-2 vaccine hesitancy in a sample of US adults: Role of perceived satisfaction with health, access to healthcare, and attention to COVID-19 News. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 9. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.665724

- Batra, K., Sharma, M., Dai, C. -L., … Khubchandani, J. (2022). COVID-19 booster vaccination hesitancy in the United States: A multi-theory-model (MTM)-based national assessment. Vaccines, 10(5), 758. doi:10.3390/vaccines10050758

- BMJ. (2022). It’s time to redouble and refocus our efforts to fight covid, not retreat. The BMJ, 379, o2423. doi:10.1136/bmj.o2423

- Burki, T. K. (2022). Omicron variant and booster COVID-19 vaccines. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 10(2), e17. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00559-2

- Celardo, I., Pace, L., Cifaldi, L., Gaudio, C., … Barnaba, V. (2020). The immune system view of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Biology Direct, 15(1), 30. doi:10.1186/s13062-020-00283-2

- Clay, L. A., & Rogus, S. (2021). Food access worries, food assistance use, purchasing behavior, and food insecurity among new yorkers during COVID-19. Frontiers in Nutrition, 8, 8. doi:10.3389/fnut.2021.647365

- Cohn, E., Chimowitz, M., Long, T., Varma, J. K., … Chokshi, D. A. (2022). The effect of a proof-of-vaccination requirement, incentive payments, and employer-based mandates on COVID-19 vaccination rates in New York City: A synthetic-control analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 7(9), e754–762. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00196-7

- de Figueiredo, A., & Larson, H. J. (2021). Exploratory study of the global intent to accept COVID-19 vaccinations. Communications Medicine, 1(1), Article 1. doi:10.1038/s43856-021-00027-x

- De Jesus, M., Ramachandra, S. S., Jafflin, Z., Maliti, I., Daughtery, A., Shapiro, B. … Jackson, M. C. (2021). The environmental and social determinants of health matter in a pandemic: Predictors of COVID-19 case and death rates in New York City. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8416. doi:10.3390/ijerph18168416

- Dorabawila, V., Hoefer, D., Bauer, U. E., Bassett, M. T., Lutterloh, E., … Rosenberg, E. S. (2022). Effectiveness of the BNT162b2 vaccine among children 5-11 and 12-17 years in New York after the Emergence of the Omicron Variant (p. 2022.02.25.22271454). medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2022.02.25.22271454

- El-Mohandes, A., Ratzan, S. C., Rauh, L., Ngo, V., Rabin, K., Kimball, S. … Freudenberg, N. (2020). COVID-19: A barometer for social justice in New York City. American Journal of Public Health, 110(11), e1–3. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2020.305939

- El-Mohandes, A., White, T. M., Wyka, K., Rauh, L., Rabin, K., Kimball, S. H. … Lazarus, J. V. (2021). COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among adults in four major US metropolitan areas and nationwide. Scientific Reports, 11(1), Article 1. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-00794-6

- Feingold, J. H., Peccoralo, L., Chan, C. C., Kaplan, C. A., Kaye-Kauderer, H., Charney, D. … Ripp, J. (2021). Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on frontline health care workers during the pandemic surge in New York City. Chronic Stress, 5, 2470547020977891. doi:10.1177/2470547020977891

- Fitzpatrick, M. C., Shah, A., Moghadas, S. M., Vilches, T., Pandey, A., … Galvani, A. 2022October5A fall COVID-19 booster campaign could save thousands of lives, billions of dollars. To the Point, The Commonwealth Fund. 10.26099/hy8p-mf92.

- Gostin, L. O. (2021). COVID-19 vaccine mandates—A wider freedom. JAMA Health Forum, 2(10), e213852. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.3852

- Greene, S. K., Tabaei, B. P., Culp, G. M., Levin-Rector, A., Kishore, N., … Baumgartner, J. (2022). Effects of return-to-office, public schools reopening, and vaccination mandates on COVID-19 cases among municipal employee residents of New York City (p. 2022.10.17.22280652). medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2022.10.17.22280652

- Hamel, L., Kirzinger, A., Lopes, L., Kearney, A., Sparks, G., … Brodie, M. (2021). KFF COVID-19 vaccine monitor: January 2021 - Vaccine Hesitancy. KFF, 27 January. https://www.kff.org/report-section/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-january-2021-vaccine-hesitancy/

- Huang, Y., & Li, R. (2022). The lockdown, mobility, and spatial health disparities in COVID-19 pandemic: A case study of New York City. Cities, 122, 103549. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2021.103549

- Jones, H. E., Manze, M., Ngo, V., Lamberson, P., … Freudenberg, N. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on college students. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 98(2), 187–196. doi:10.1007/s11524-020-00506-x

- Karaivanov, A., Kim, D., Lu, S. E., … Shigeoka, H. (2022). COVID-19 vaccination mandates and vaccine uptake. Nature Human Behaviour, 1–10. doi:10.1038/s41562-022-01363-1

- Kim, B., Rundle, A. G., Goodwin, A. T. S., Morrison, C. N., Branas, C. C., El-Sadr, W., … Duncan, D. T. (2021). COVID-19 testing, case, and death rates and spatial socio-demographics in New York City: An ecological analysis as of June 2020. Health & Place, 68, 102539. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2021.102539

- Kirzinger, A., Audrey, K., Hamel, L., … Brodie, M. (2021, November 16). KFF COVID-19 vaccine monitor: the increasing importance of partisanship in predicting COVID-19 vaccination status. KFF. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/importance-of-partisanship-predicting-vaccination-status/

- Kirzinger, A., Sparks, G., & Brodie, M. (2021, July 13). KFF COVID-19 vaccine monitor: In their own words, six months later. KFF. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-in-their-own-words-six-months-later/

- Latkin, C., Dayton, L. A., Yi, G., Konstantopoulos, A., Park, J., Maulsby, C., … Kong, X. (2021). COVID-19 vaccine intentions in the United States, a social-ecological framework. Vaccine, 39(16), 2288–2294. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.02.058

- Lazarus, J. V., Ratzan, S. C., Palayew, A., Gostin, L. O., Larson, H. J., Rabin, K. … El-Mohandes, A. (2020). A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nature Medicine, 1–4. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9

- Lazarus, J. V., Romero, D., Kopka, C. J. (2022). A multinational Delphi consensus to end the COVID-19 public health threat. Nature, 611, 332–345. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05398-2.

- Lazarus, J. V., Wyka, K., Rauh, L., Rabin, K., Ratzan, S., Gostin, L. O. … El-Mohandes, A. (2020). Hesitant or Not? The association of age, gender, and education with potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine: A country-level analysis. Journal of Health Communication, 25(10), 799–807. doi:10.1080/10810730.2020.1868630

- Lazarus, J. V., Wyka, K., White, T. M., Picchio, C. A., Rabin, K., Ratzan, S. C. … El-Mohandes, A. (2022). Revisiting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy around the world using data from 23 countries in 2021. Nature Communications, 13(1), 3801. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-31441-x

- Lazić, A., & Žeželj, I. (2021). A systematic review of narrative interventions: Lessons for countering anti-vaccination conspiracy theories and misinformation. Public Understanding of Science, 30(6), 644–670. doi:10.1177/09636625211011881

- Levine, Hallie.(2022). Covid fatigue is making the pandemic worse—And prolonging its end, experts say. CNBC. Retrieved October 17, 2022, from https://www.cnbc.com/2022/02/09/experts-covid-fatigue-is-making-pandemic-worse-prolonging-its-end.html

- Lieberman-Cribbin, W., Tuminello, S., Flores, R. M., & Taioli, E. (2020). Disparities in COVID-19 testing and positivity in New York City. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 59(3), 326–332. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.005

- Li, M. -H., Haynes, K., Kulkarni, R., … Siddique, A. B. (2022). Determinants of voluntary compliance: COVID-19 mitigation. Social Science & Medicine, 310(1982), 115308. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115308

- López-Castro, T., Brandt, L., Anthonipillai, N. J., Espinosa, A., … Melara, R. (2021). Experiences, impacts and mental health functioning during a COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown: Data from a diverse New York City sample of college students. PloS One, 16(4), e0249768. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0249768

- MacDonald, N. E., & SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. (2015). Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine, 33(34), 4161–4164. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036

- Mondal, P., Sinharoy, A., … Su, L. (2021). Sociodemographic predictors of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: A nationwide US-based survey study. Public Health, 198, 252–259. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2021.07.028

- NYC Health. (n.d.). COVID-19: Data Trends and Totals. Retrieved October 6, 2022, from https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data-totals.page

- NYC Health. (n.d.). COVID-19: Vaccination Workplace Requirement. Retrieved October 6, 2022, from https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-vaccine-workplace-requirement.page

- Padamsee, T. J., Bond, R. M., Dixon, G. N., Hovick, S. R., Na, K., Nisbet, E. C. … Garrett, R. K. (2022). Changes in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among black and white individuals in the US. The JAMA Network Open, 5(1), e2144470. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.44470

- Palmedo, P. C., Rauh, L., Lathan, H. S., … Ratzan, S. C. (2022). Exploring Distrust in the Wait and See: Lessons for Vaccine Communication. The American Behavioral Scientist, 0(0). doi:10.1177/00027642211062865

- Pertwee, E., Simas, C., … Larson, H. J. (2022). An epidemic of uncertainty: Rumors, conspiracy theories and vaccine hesitancy. Nature Medicine, 28(3), Article 3 doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01728-z

- Purnat, T., Wilson, H., Nguyen, T., … Briand, S. (2021). EARS – a WHO platform for AI-Supported real-time online social listening of COVID-19 conversations. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 281. doi:10.3233/SHTI210330

- Rostami, A., Sepidarkish, M., Leeflang, M. M. G., Riahi, S. M., Nourollahpour Shiadeh, M., Esfandyari, S. … Gasser, R. B. (2021). SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Microbiology and Infection: The Official Publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 27(3), 331–340. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2020.10.020

- Roy, D. N., Biswas, M., Islam, E., & Azam, M. S. (2022). Potential factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy: A systematic review. PloS One, 17(3), e0265496. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0265496

- Shekhar, R., Sheikh, A. B., Upadhyay, S., Singh, M., Kottewar, S., Mir, H. … Pal, S. (2021). covid-19 vaccine acceptance among health care workers in the United States. Vaccines, 9(2), Article 2 doi:10.3390/vaccines9020119

- Shi, Y., Wang, Y., Shao, C., Huang, J., Gan, J., Huang, X. … Melino, G. (2020). COVID-19 infection: The perspectives on immune responses. Cell Death & Differentiation, 27(5), Article 5 doi:10.1038/s41418-020-0530-3

- Solis Arce, J. S., Warren, S. S., Meriggi, N. F., Scacco, A., McMurry, N., … Voors, M. (2021). COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in low- and middle-income countries. Nature Medicine, 27(8), 1385–1395. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01454-y

- Sparks, G., Kirzinger, A., … Brodie, M. (2021, June 11). KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: Profile Of The Unvaccinated. KFF. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-profile-of-the-unvaccinated/

- Talmor, Nina., Ramachandran, Abhinay., Brosnahan, Shari., Shah, Binita., Bangalore, Sripal., Razzouk, Louai., … Attubato, Michael. (2022). Invasive management of acute myocardial infarctions during the initial wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of Invasive Cardiology, 34(1). https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/jic/original-contribution/invasive-management-acute-myocardial-infarctions-during-initial-wave

- Teasdale, C. A., Ratzan, S., Rauh, L., Lathan, H. S., Kimball, S., … El-Mohandes, A. (2022). COVID-19 vaccine coverage and hesitancy among New York City Parents of children aged 5-11 years. American Journal of Public Health, 112(6), 931–936. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2022.306784

- Teasdale, C. A., Ratzan, S., Stuart Lathan, H., Rauh, L., Kimball, S., … El-Mohandes, A. (2022). Acceptability of COVID-19 vaccine mandates among New York City parents, November 2021. Vaccine, 40(26), 3540–3545. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.05.010

- Trent, M., Seale, H., Chughtai, A. A., Salmon, D., … MacIntyre, C. R. (2022). Trust in government, intention to vaccinate and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: A comparative survey of five large cities in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia. Vaccine, 40(17), 2498–2505. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.06.048

- US Census Bureau. (2020). 2019 American Community Survey Single-Year Estimates. Census.Gov. Retrieved October 17, 2022, from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2020/acs-1year.html

- Wilhite, J. A., Zabar, S., Gillespie, C., Hauck, K., Horlick, M., Greene, R. E. … Adams, J. (2022). “I don’t trust it”: Use of a routine OSCE to identify core communication skills required for counseling a vaccine-hesitant patient. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 37(9), 2330–2334. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07495-4

- Wittenberg, E., Goldsmith, J. V., Chen, C., Prince-Paul, M., … Johnson, R. R. (2021). Opportunities to improve COVID-19 provider communication resources: A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling, 104(3), 438–451. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2020.12.031

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. (2020). Pandemic fatigue: Reinvigorating the public to prevent COVID-19: policy framework for supporting pandemic prevention and management: revised version November 2020 (WHO/EURO:2020-1573-41324-56242). World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/337574