Abstract

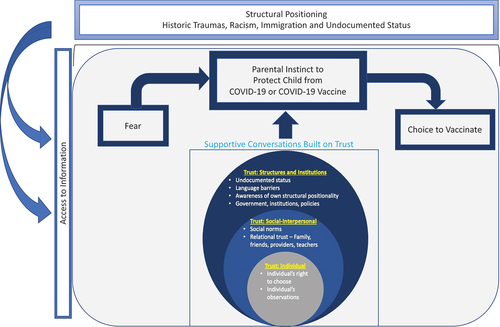

National and state data show low adoption of childhood COVID-19 vaccinations, despite emergency use authorizations and availability. We conducted 24 in-depth, semi-structured interviews with Black and Latino parents in New York City (15 in English, 9 in Spanish), who were undecided or somewhat likely to vaccinate their 5 to 11-year-old children in early 2022. The interviews explored the evolution of parental perceptions on childhood COVID-19 vaccines, and were analyzed using a matrix-driven rapid approach to thematic analysis. We present our findings as themes oriented around trust at three levels of the social ecological model. In summary, we found that structural positionality and historical traumas of participants seeded mistrust in institutions and government. This led to parental reliance on personal observations, conversations, and norms within social groups for vaccine decision-making. Our findings also describe key features of trust-building, supportive conversations that shaped the thinking of undecided parents. This study demonstrates how relational trust becomes a key factor in parental vaccine decision-making, and suggests the potential power of community ambassador models of vaccination promotion for increasing success and rebuilding trust with members of the “movable middle.”

The COVID-19 pandemic mitigation strategies have largely rested on the rollout of vaccinations. Due to the staggered availability of clinical trial data and the sequential process of United States Food and Drug Administration (F.D.A.) review and authorization, COVID-19 vaccine implementation was phased-in by age group. Emergency use authorization was extended to pediatric populations aged 5 to 12 in November 2021.

At the onset of authorization, a Kaiser Family Foundation poll identified roughly 34% of parents eager to vaccinate their children upon federal approval, another third opted to “wait and see,” and the remaining third refused to vaccinate their children. This survey predicted that an initial surge of uptake would lose momentum in the absence of any policy or implementation changes (Kates, Michaud, Tolbert, Artiga, & Orgera, Citation2021). Aligned to this projection and despite the availability of COVID-19 childhood vaccines, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) September 14, 2022 national data report only 37.8% of children ages 5 to 11 have received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose (Ndugga, Hill, Artiga, & Haldar, Citation2022).

Parental perspectives toward childhood COVID-19 vaccination have been largely drawn from survey data that corroborate the higher rates of reluctance among Black and Latino parents (Larson et al., Citation2018). While the national data for childhood COVID-19 vaccination rate is not stratified by race and ethnicity, the longitudinal vaccination rates of adults who are children’s medical consenters indicate that Blacks and Latinos have had slower vaccination rates than their White counterparts, with disparities only having narrowed or reversed over time. In New York City (NYC), September 2022 childhood vaccination rates among Black (44%) and Latino (55%) children 5 to 12 are currently higher than that of white (39%) children (COVID-19: Data on Vaccines - (NYC Health, Citation2022)). This is an encouraging development that could be attributed to the city’s public health initiatives, but vaccination rates have stalled and many parents remain hesitant. NYC vaccination rate among 5- to 12-year-old children was 49% in February 2022, increasing to 57.1% in September 2022, and culminating at 58.5% in February 2023 (: Data on Vaccines—NYC Health, Citation2023).

COVID-19 incidence and mortality rates disproportionately affected Blacks and Latinos in the United States, reflecting the structural racism that patterns these communities’ experiences. Structural racism is a critical epidemiological framework in delineating COVID-19 health disparities (Tan, deSouza, & Raifman, Citation2022), and underscores the need for thoughtfully tailored COVID-19 vaccination implementation and communication strategies. Parents’ hesitancy toward the COVID-19 vaccine is rooted in a model of trust, balancing confidence in the vaccine product, provider, and policymaker. External levers of generalized trust in society, historical traumas that erode trust in institutions, and influencers such as social relationships, politicians and community leaders, push and pull the scales of vaccine trust (Larson et al., Citation2018; Latkin, Dayton, Yi, Konstantopoulos, & Boodram, Citation2021). Social norms in favor of vaccination have been shown to positively impact intention to vaccinate for HPV and flu (de Bruin, Parker, Galesic, & Vardavas, Citation2019; Stout, Christy, Winger, Vadaparampil, & Mosher, Citation2020), but the converse also holds in that socially normalized vaccine mistrust adversely affects intention to vaccinate (Ledford et al., Citation2022).

The goals of this paper are to elucidate and describe central tensions in Black and Latino parents’ decision-making about childhood COVID-19 vaccination. By highlighting the thinking processes of vaccine hesitant parents, this research aims to inform the vaccine trust model and vaccination outreach strategies for parents from marginalized communities.

Methods

To explore Black and Latino parents’ dynamic thought processes regarding childhood vaccination in early 2022, we conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews. These interviews focused on the evolution of parents’ thinking alongside individual and interpersonal experiences amid shifting policies and mandates. This research was reviewed and approved by the City University of New York (CUNY) Institutional Review Board (2022–0009-PHHP).

Participant Recruitment

To recruit interviewees, we partnered with the CUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy’s New York Vaccine Literacy Campaign (NY VLC) and the Harlem Health Initiative (HHI). Between January and May 2022, NY VLC and HHI staff emailed a project description and screener links (in English and Spanish) to leaders at partner organizations serving Black and Latino parents across NYC. The screener solicited information on likelihood of pursuing COVID-19 vaccination for their child, using the following 5-item Likert question: “How likely are you to get your 5–11-year-old child vaccinated against COVID-19, now that the vaccine is available to 5–11-year-olds?” Due to stalled vaccination rates, we were interested in understanding what kept parents in the “movable middle.” Those with intent or uncertainty around vaccination are more likely to vaccinate after appropriate interventions than those who are “reluctant” (Barli & Dhanini, Citation2021; Omari et al., Citation2022). Therefore, parents of children 5–11 years old who reported being “not sure/undecided” or “somewhat likely” to vaccinate their children in the screener were eligible for interview, even if the child was vaccinated by the time of the interview. Identifying patterns among the “movable middle” gives room to explore opportunities in optimizing vaccination uptake. Two participants’ children received the COVID-19 vaccine by the time of the interview, offering the research team the opportunity to understand what factors had moved the participants to ultimately vaccinate their child. We contacted these individuals via e-mail or text to arrange Zoom-based interviews (Zoom Video Communications, Inc.).

Data Collection

Interviews were conducted in either English or Spanish by KL, ET, and CW. After participants and interviewers reviewed the consent, the interviewers discussed the following topics using a semi-structured guide (Appendix A): experiences during COVID-19, attitudes toward the adult and children’s COVID-19 vaccine, decision-making processes, and information sources. Interviews ranged from 30 minutes to 1 hour and were audio recorded.

Data Analysis

Interviews were professionally transcribed verbatim and translated into English if originally in Spanish. Analysts [KL, ET, and CW] met weekly to discuss interviews. Based on these discussions and original research questions, we developed a matrix-driven rapid approach to analysis that emphasized summarizing rather than coding, and centered team communication to triangulate emergent findings (Vindrola-Padros & Johnson, Citation2020). Drawing from the Framework Method (Gale, Heath, Cameron, Rashid, & Redwood, Citation2013), we charted interview excerpts into matrices wherein each row was a participant and each column a topic (e.g., motivators of adult vaccination, barriers to adult vaccination, motivators of childhood vaccination, barriers to childhood vaccination). While topics were of a priori interest, analysis focused on participants’ emic understandings and experiences. After a batch of 10 English interviews, analysts individually summarized key learnings within and across topics and participated in consensus discussions to identify convergent ideas. We repeated this process three more times (for two batches of Spanish interviews, and one more batch of English interviews). Through summarizing and discussion, we built up grounded themes and mapped them onto constructs of the social ecological model, which helped to elucidate the interplay between interpersonal, structural and systemic influences on an individual’s health behavior (Golden & Wendel, Citation2020).

Results

Sample Description

We conducted a total of 24 interviews, with 15 English-speaking and 9 monolingual Spanish-speaking parents. The majority (95.83%) of the participants were female; 41.6% were residents in the Bronx, 20.8% in Brooklyn, 20.8% in Manhattan, 8.3% in Queens, and 8.3% in Staten Island. Average age of children was 7.83 ± 1.8 years (range 5–11 years). Half reported an annual household income less than $39,000 and had public insurance coverage, whether Medicaid, Medicare or dual eligibility, while 20.83% were uninsured and receiving medical services through the NYC Health and Hospitals’ NYC Care, a low to no-cost healthcare access program for the uninsured. Of the 9 monolingual Spanish-speaking participants, 55.6% disclosed their undocumented status ().

Table 1. Participant demographics

Qualitative Findings

The following sections, guided by the social ecological model, highlight the two most urgent themes at the structural, social/interpersonal, and individual levels. In our final section, we explore features of the supportive conversations which moved participants from less to more likely to vaccinate. summarizes our findings.

Structural Level

Historical and Structural Roots of Fear and Suspicion

Historical, structural, and institutional disparities foregrounded participants’ suspicions around the COVID-19 vaccines. Participants noted the U.S. government’s involvement in medical experimentation without consent on communities of color. One participant, for instance, illustrated this by appearing to reference Henrietta Lacks, a Black American woman whose cells (“HeLa cells”) continue to be used in biomedical research decades after her cancer death.

“The US does not have a good history when it comes to medical innovations and breakthroughs and new vaccines. I mean, honestly, they’re still using the blood of that one girl, that one African American girl (EN02, Latina).

Participants, particularly monolingual Spanish speakers, highlighted similar issues in Latin America, noting, in two cases, the syphilis experiments that the US government imposed on Guatemalans without informed consent in the 1940s. This historical precedent drove sentiments of mistrust toward US medical research.

Participants also broadly contended with the intersection of structural racism and socioeconomic status that have eroded the health outcomes of communities of color. In one participant’s experience, unsafe environmental hazards in NYC’s Housing Authority public housing posed grave health concerns which de-prioritized the COVID-19 childhood vaccine.

“I’m actually waiting for the apartment to get fixed, because that has contributed to him [son] being sick most of the time … So, to me, it’ll defeat the purpose of him getting vaccinated to come home to a house that’s not fully safe, which they’re in the middle of fixing it up right now.” (EN18, Black)

Finally, we heard repeatedly about a heightened awareness of positionality and related fears of deportation and insufficient access to health care among undocumented monolingual Spanish-speaking participants. As one participant said,

“Parents are scared. Why are they scared? Because most parents don’t have documents. And sometimes people are afraid to speak up, because they think they can get in trouble. They are afraid, they think that maybe if they ask them a question about their address, they are afraid of being deported. In my school there 85% of Mexican and Hispanic parents. Most of them do not have documents.” (SP02, Latina)

Suspicion and the Erosion of Institutional Trust

The historical and structural inequities described above informed how participants interpreted national and city COVID-19 vaccine strategies and communications. They generally found the information they received about vaccination to be confusing and further, suspicious.

In particular, we heard extensively about the suspicion generated by NYC’s $100 incentive program for COVID-19 vaccinations. A key issue for participants was the potential for coercion:

“I was not going to, there’s no way you couldn’t pay me, and the fact that they were paying people to do it, I was just, it was so disgusting to me […] Because that was aimed at people who need the money. Like let’s see you force, you cut off people’s money, you cut off people, supplies, cut off people’s access to work, you cut off people’s access to resources, and you tell them they have to do this thing in order to survive. What are they going to do?” (EN14, Black, White, Native American)

Incentives were only described by parents as appealing, in some cases, to older children.

The vaccine mandate for continued employment was another important local policy feature affecting institutional trust. We heard clearly from participants that many of them were vaccinated for COVID-19, albeit reluctantly, because of employer mandates. Parents with largely negative or hesitant views of vaccination explained to us that if there were a vaccination mandate in NYC schools, they would vaccinate their children. At the same time, mandates further destabilized trust in public health institutions.

“I almost felt forced. Actually, not almost. I did feel forced. I was very nervous about taking it. I’m still a bit uneasy, but I mean, it’s done. What can I do?” (EN17, Black, Latina)

Instead of showing parents the benefits of vaccination and improving their likelihood of vaccinating their children, many participants either felt some regret or still seemed to be searching for a justifiable rationale for having vaccinated themselves. For many parents, not having had a choice for their own vaccination appears to have solidified their hesitation around childhood vaccination.

Interpersonal Level

Relying on Relational Trust

In an environment where institutional trust had been eroded through structural exclusion and problematic public health messaging, participants turned to the firsthand experiences of their social network to gain information about the vaccine. Personal experience became a source of trusted primary data, a process of emergent reliance on what we call relational trust. Through conversations with friends and neighbors, many participants came to prefer a “wait and see” approach to childhood vaccination, observing the experiences of others in their community before making a decision for their own family.

“I just needed a little more time to let it – you know, to do a little more research. […] And you know, and see how other kids, after they took the vaccine, how they felt and you know, and just to talk to some other people that I trusted like my doctor and my older brother. His kids took the vaccine.” (EN05, Black)

“Some families or friends that I have, I ask them what happens to kids, if they get a fever or if the arm hurts where they got it, they say yes, that their little arms hurt a day and some do get a fever, some don’t, so, well … I’m realizing that, well, it’s good to get it, but like I said, I can’t decide yet if the kids should get it” (SP04, Latina)

Using the “wait and see” approach, parents navigated their social world to seek trustworthy information via observation and conversation. Trustworthy “observational” data was often generated from the parents of school-age children in their neighborhood. Importantly, these observations did not inherently increase comfort in the childhood COVID vaccine, particularly in communities where the vaccine rollout felt rushed or coercive:

“And as long as my information is going to come from other people’s experiences, which have not been great—it’s not been great not in my neighborhood anyway. Then it’s not, you know, not good feelings towards that.” (EN14, Black, White, Native American)

The Role of Social Norms in Navigating Vaccination Decisions

As this last quote suggests, social network norms also shaped participants’ vaccination action and inaction. As one participant stated, “so I guess when I feel like, okay, you know what, there are a lot more parents coming forward, it could also help me go forward with my decision as well” (EN06, Black). This added another dimension to the “wait and see” approach, with participants deciding to vaccinate their child not only at a certain threshold of comfort or evidence, but also when it felt socially acceptable to do so. Given this tension, some participants spoke of the difficulty navigating conflicting messaging from their social circle. One participant in particular described hearing divergent opinions from her mixed-race friend group, whose members had differing levels of trust in the healthcare system:

“I have a lot more white friends, because my wife is also white […] And so like all my white friends, like, everyone’s done it [gotten vaccinated], and so it just looks like my black friends are the ones who like, haven’t done it […] I’m hearing like it’s good, and I’m hearing like, no, like, don’t be crazy, don’t do it” (EN01, Black)

Navigating these vaccination norms, especially for parents who are vaccine-hesitant, sometimes increased social isolation:

“Most [of our friends] were very pro-vaccine and at the time, we weren’t vaccinated yet. So, if you weren’t vaccinated yet, they didn’t want to be around you and it was very isolating […] and the children they didn’t really understand, they still don’t understand” (EN13, Black)

These experiences increased social pressure to vaccinate their child. In fact, the potential return to social activities and playdates with other children was a strong motivator:

“I want her to enjoy time with her friends and have a social life because that’s important too, for children interacting with other children growing up so I don’t want to have her not being able to do events because she’s not vaccinated” (EN16, Latina)

Thus, the social and interpersonal dynamics of childhood COVID-19 vaccination, as experienced by participants, created competing priorities for parental decision-making. Navigating vaccination decisions, parents felt pressure to balance the need to protect children from disease with social opportunities that are critical to children’s development.

Individual Level

Tensions in Protecting Children

Perhaps unsurprisingly, a core value that animated much of parents’ thinking about COVID-19 and vaccination was the importance of protecting their children. However, there were only a few cases in our undecided sample where COVID-19 vaccination was seen as a form of protection. Instead, parents frequently described needing to protect their children from feared outcomes associated with COVID-19 vaccination, more than from COVID-19 infection itself. These feared outcomes have been well documented in the literature (Suran, Citation2022), and include fears of putting harmful chemicals into their children’s bodies, unknown side effects, and long-term developmental effects. Parents did fear COVID-19, but some felt that they could protect their children better by using other strategies (distancing, masking, hand-sanitizing). The “responsibility” (EN13, Black) to make a vaccination decision for children so early in the lifecourse, amid conflicting information and confusion, weighed heavily for both English and Spanish speakers.

“I’m an adult, so there’s not too much that can change in my body, but they’re still growing. So, you know, even though there’s science that supports it, but there’s also science that’s saying that they’re not sure because this stuff is too new. So, it’s one thing to put myself at risk, but then it’s another thing to put my children at risk.” (EN15, Black)

Protecting children with other health conditions led to even more conflicted decision-making. Many parents in this situation wanted to but still did not fully understand the potential impact of interactions between COVID-19 vaccination and their child’s condition, such as asthma, Tourette’s syndrome, autism, and ADHD. Confusion stemmed from both lack of information and insufficient access to converse with clinicians about these concerns.

The idea of protection reached beyond the child’s health to protection from (further) financial insecurity, separation, and even smaller scale disruptions to school schedules. This dynamic was particularly prevalent in interviews with monolingual Spanish speakers, and with an English-speaking participant who became the caretaker of her sister’s children after her sister died from COVID-19:

“I put foreign things into my body just because of what they told us to do, or I will lose my job, and I now have her [sister’s] kids to take care of. So, it was a life-or-death decision.” (EN18, Black)

Finally, school presented a complex landscape for parents as it was generally seen as protective socially and academically, but dangerous from the perspective of COVID-19 exposure. As one parent said, “I was afraid he could get infected because, in schools, children are exposed to everything. We didn’t even want to let him go, we wanted him to study from home, but the following year it was going to be complicated for him to go back to school and start socializing again, so we decided to sign him up [for school].” (SP09, Latina)

Interestingly, policy changes could potentially shift the calculus of protection. When NYC public schools dropped their mask mandate in Spring 2022, several parents mentioned that they would be more likely now to vaccinate without the protection of masks in school. One parent described her thinking, “One [child] coughs, the other one has a fever, that happens, so I’ll take you over to get vaccinated and you’ll be a bit more protected from all of that.” (SP04, Latina)

Dynamics of Choice for Parents and Children

Parents in our sample repeatedly and proactively threaded the importance of making their own choice about vaccination. As described earlier, many parents in our sample felt “forced” to vaccinate. In this context, preserving the ability to make a choice about childhood vaccination, and specifically the decision to wait, took on particular meaning: “I even feel calm because I don’t feel the pressure that I have to vaccinate my girls. I felt like I was under pressure. It is like a very heavy burden, because you make a decision that is not your own, it is not yours.” (SP06, Latina)

Some parents decided to center their children’s choice, particularly for older children.

“If he would come up to me and tell me mom, could I just go get my vaccines, I would say like okay, let’s just go.” (EN07, Latina, Child: 7-year-old)

Participant Recommendations: Trust-Building Communications and Supportive Conversations

Transparent Institutional Communications That Build Trust

To reframe structurally-rooted suspicions, communication strategies require more than top-down public health messaging alone, but also demand a responsive, community-engaged approach (12 COVID-19 Vaccination Strategies for Your Community, Citation2022). As one participant stated,

“If I felt I can’t trust the top officials, then why am I going to trust them enough to say, ‘Oh, I can put the vaccine to my child?” (EN18, Black)

This same participant went on to emphasize the importance of direct communication to the public and transparency about current scientific knowledge:

“They [public officials] need to be transparent [and say] ‘Yes, we know these things, but we also don’t know enough. This is new to us, too.’ So, if they can just acknowledge that, [if] I feel I can hear that come out of, let’s say, Mayor Adams’ mouth, then I will be more trustful and be more, “Okay, I can believe them. I can give my child this.” (EN18, Black)

Supportive Conversations

In facing the choice about whether to vaccinate their 5- to 11-year-old children, supportive conversations and relationships proved immensely important. Trusted data about the vaccine came from conversations with respected community members, including teachers, family, doctors, and friends. As example, one participant spoke poignantly of school staff who engaged her around vaccination: ”[The teacher] said it was my decision so that I could protect her [her child] and be calm, that it is better to vaccinate her, but that it was my decision, that I made the decision I made, and that they were there to support me.” (SP06, Latina)

While access to health care was a challenge for many, those with stronger connections to physicians described interactions that took place over time which encouraged vaccination while preserving choice, though sometimes more subtly. One parent described a pediatrician who understood her child’s particular health concerns, while encouraging COVID-19 vaccination by helping her develop what felt like a workable timeline (start with the flu vaccine, then the COVID-19 vaccine, since the child often gets ill post-vaccine). Another parent described her own phased decision with her doctor, which ultimately led to her choice to get vaccinated. The doctor told them:

“That it was necessary to make sure during this time that the virus would not get worse. That I had to take the precaution for the children. And that he [the doctor] had been vaccinated and that he wasn’t dead as people said. He did it [spoke with me in this way] for several months. It was like therapy. Every time I went. Because I suffer from high blood pressure, so he always checked my blood pressure to see how I was doing. And every month, every month I went, he was always talking to me, “Come on, get it. Get it next month.” (SP05, Latina)

We should note that while this persistent approach resulted in vaccination for this participant, others described such proponents as vaccine “pushers,” which made them more suspicious. What may have been different here was what appears to be a dedicated and ongoing engagement with the participants’ multiple rationales for not vaccinating.

Some participants had learned to educate others about COVID-19, a process that also served to educate them. Specifically, two parents had recently taken jobs as “community ambassadors,” helping organizations and individuals to combat COVID-19 in their neighborhoods. While both described themselves as initially vaccine hesitant, one illustrated their shift in thinking, especially for childhood vaccination, saying that their views changed “with the help of my job. Like, being around people that were a lot more knowledgeable than me, and explaining certain things definitely helped.” (EN15, Black) Partly due to this shift, this parent’s child had recently been vaccinated.

Discussion

The present study builds on previous survey work characterizing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Black and Latino NYC parents of children ages 5–11 (Teasdale et al., Citation2022), elucidating the structural, interpersonal, individual dynamics of vaccine uptake and hesitancy. This qualitative study adds context to the reasons why parents leaned toward or away from COVID-19 vaccination, providing a rich description of the “movable middle.”

Value of Supportive Conversations

The themes above highlight the critical role that empathetic, supportive conversations can play in vaccination decision-making among hesitant parents. Participants described interactions with trusted community members which facilitated decisions to vaccinate. These conversations shared similar features and included: space for questions, listening to concerns empathetically without judgment, and offering support regardless of attitudes. Importantly, the most effective supportive conversations stemmed from repeated, intentional interactions over time, giving participants space to process new information while preserving their ability to choose. While it may be the case that no single conversation “convinced” a parent to vaccinate their child, multiple conversations served to build both trust and confidence in vaccination. In this way, our data aligns with the recommendations of the Presidential COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force, which concludes, “through tailored messages, trusted messengers, and meeting people ‘where they are,’ our nation can better mitigate health inequities during public health emergencies.” (Presidential COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force: Final Report and Recommendations, Citation2021, p. 23) While supportive conversations were critical in decision-making, inaccessibility of language-concordant information and services posed barriers. Several monolingual Spanish-speaking participants discussed challenges in communicating with their English-speaking providers. They were also misinformed that accessing healthcare services would expose their undocumented status, an inaccuracy that could be the function of a broader issue of limited access to information tailored to cultural context in one’s preferred language.

Our data also highlight the benefit of “community ambassadors” who can leverage community social ties and networks to build trust in facilitating supportive vaccine conversation. The community ambassador model has helped increase COVID-19 vaccination among Latino communities in California (Marquez et al., Citation2021) and North Carolina (Dewitt-Feldman, Robinson, Thach, Tipton, & McCall, Citation2021) by providing an avenue for community members to share personal experiences and obtain public health information from a trusted source. As these programs and our data indicate, community ambassador programs can have positive cascading effects on health communication, where individuals who benefit from supportive conversations go on to share their experiences with their social networks, lowering barriers to engagement with local public health initiatives.

Community Ambassadors to Safeguard Relational Trust

During the pandemic, NYC established a Public Health Corps to expand outreach and education on COVID-19 through partnered community- and faith-based organizations (NYC Health, Citation2022). The Community Health Worker model is another evidence-based fixture in facilitating health promotion work (CHW Network NYC, Citation2020; Supporting Peers and Community Health Workers - (NYC Health, Citation2022)).

Building on the success of these existing models, the proposed community ambassador model is unique in its broader mobilization of community members into the work of promoting vaccine education, irrespective of employment or connection with a government, healthcare, or social service organization. Leveraging local social networks, community ambassadors are able to train other ambassadors within their respective communities (12 COVID-19 Vaccination Strategies for Your Community, Citation2022). This allows for a multiplication of lay community members to contribute to the iterative process of trust-building and leverages relational trust in reducing vaccine hesitancy. Our data identified school staff, family, friends, and providers as trustworthy sources, whose information around childhood COVID-19 vaccines influenced participants’ position.

Our research also highlights the complex effects of vaccination mandates. As our findings indicate, mandates were effective in getting hesitant adult participants vaccinated (as recent modeling research also suggests) (Cohn, Chimowitz, Long, Varma, & Chokshi, Citation2022), and likely would have been effective in getting children vaccinated if required for school attendance. At the same time, mandates sometimes left participants with persistent regrets and questions that further undermined their trust in public health institutions. In the absence of a childhood vaccination mandate, parents with uncomfortable experiences from their own mandated vaccination waited for better information before vaccinating their children. However, the mandate experience alienated them from public health institutions as sources of information and support in decision-making, leaving primarily their interpersonal networks. In thinking about the use of mandates going forward, we see a tension between the urgency of increasing vaccination levels via mandates, and the damage that mandates can inflict on trust when not accompanied by trusted social support and information. By providing ongoing, informed, conversational support, community ambassadors might play a key role in ensuring that mandates do not alienate hesitant individuals from public health institutional messaging and practices.

Strengths and Limitations

The authors acknowledge several limitations. While our sample included residents of all NYC boroughs, there may be perspectives on vaccination not captured in the present study. As the one-time global epicenter, NYC residents experienced rapid and evolving mitigation strategies including the shutdown of non-essential businesses and schools, mask mandates and employer vaccine mandates (Ferré-Sadurní & Cramer, Citation2020; Garsd, Citation2021; Goldstein & Otterman, Citation2022; Governor Cuomo Signs the “New York State on PAUSE” Executive Order | Governor Kathy Hochul, Citation2020; State of New York Executive Chamber Executive Order No. 202.17, Citation2020 (Ramachandran, Kusisto, & Honan, Citation2020; Thompson et al., Citation2020)). In addition, only participants with availability and access to join a 60-minute Zoom call were able to participate. Despite sampling “undecided” or “somewhat likely” individuals, there is still the potential for selection bias, in that individuals with strong views for or against vaccination were more likely to participate in an interview. Finally, our interviews captured parental attitudes at a single timepoint during the pandemic (Spring 2022). While these perspectives may evolve with changing case counts and city policies, it is our hope that these insights may inform future policies. By sampling Black and Latino parents for qualitative interviews in English and Spanish, this study centered typically underrepresented voices in public health research and lowered barriers to research participation. This study uniquely gives voice to monolingual Spanish-speakers in NYC, many of whose undocumented status amplifies the structural schema that vaccine interventions ought to reach.

Conclusion

Traversing borders and generations, the legacy of medical exploitation is embodied in communities’ distrust of government and institutions’ agenda in the public’s health (Marcelin et al., Citation2021). Black and Latino parents described awareness of the disparities they face by race, class, and documentation status, altogether forming the architecture of structural positioning. This structural schema moderated the fear that parents experienced, whether of COVID-19 or the vaccine, stirring a universal response to protect their children and impacting decisions on whom and what to trust. Our findings nuance existing models of vaccine trust and inform future implementation and communication strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the CUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy’s NY VLC and HHI and their networks of community partners for supporting recruitment for this project. In particular, we thank Hannah Stuart Lathan, Karen Ortiz, and Deborah Levine. We also benefitted immensely from input and insights from Lauren Rauh, Hannah Stuart Lathan, Dr. Karen Flórez, and Dr. Chloe Teasdale. Finally, we deeply thank our 24 participants for generously sharing their perspectives and experiences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- 12 COVID-19 Vaccination Strategies for Your Community. (2022, March 2). Centers for disease control and prevention: 12 COVID-19 vaccination strategies for your community. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/vaccinate-with-confidence/community.html

- CHW Network NYC. (2020). About community health workers. https://www.chwnetwork.org/about-chws

- Barli, S., & Dhanini, D. L. (2021). Research report & meta analysis, authored by: Final report.

- Cohn, E., Chimowitz, M., Long, T., Varma, J. K., & Chokshi, D. A. (2022). The effect of a proof-of-vaccination requirement, incentive payments, and employer-based mandates on COVID-19 vaccination rates in New York City: A synthetic-control analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 7(9), e754–762. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00196-7

- COVID-19: Data on Vaccines—NYC Health. 2022. NYC Health COVID-19: Data. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data-vaccines.page#nyc

- COVID-19: Data on Vaccines—NYC Health. (2023). https://www.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data-vaccines.page

- de Bruin, W. B., Parker, A. M., Galesic, M., & Vardavas, R. (2019). Reports of social circles’ and own vaccination behavior: A national longitudinal survey. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 38(11), 975–983. doi:10.1037/hea0000771

- Dewitt-Feldman, S., Robinson, H. J., Thach, S. B., Tipton, L., & McCall, S. (2021). Spotlight on the safety net: Bilingual, bicultural CARE health ambassadors in rural western North Carolina: A community collaboration. North Carolina Medical Journal, 82(4), 292–293. doi:10.18043/ncm.82.4.292

- Ferré-Sadurní, L., & Cramer, M. (2020, April 15). New York orders residents to wear masks in public. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/15/nyregion/coronavirus-face-masks-andrew-cuomo.html

- Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., & Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 117. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

- Garsd, J. (2021, July 26). New York City mandates municipal workers be vaccinated by mid-september. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2021/07/26/1020866525/new-york-city-mandates-municipal-workers-be-vaccinated-by-mid-september

- Golden, T. L., & Wendel, M. L. (2020). Public health’s next step in advancing equity: Re-evaluating epistemological assumptions to move social determinants from theory to practice. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 8. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00131

- Goldstein, J., & Otterman, S. (2022, March 17). What New York got wrong about the pandemic, and what it got right. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/17/nyregion/new-york-pandemic-lessons.html

- Governor Cuomo Signs the “New York State on PAUSE” Executive Order | Governor Kathy Hochul. (2020, March 20). https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-cuomo-signs-new-york-state-pause-executive-order

- Kates, J., Michaud, J., Tolbert, J., Artiga, S., & Orgera, K. (2021, October 25). Vaccinating children ages 5-11: Policy considerations for COVID-19 vaccine rollout. KFF. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/vaccinating-children-ages-5-11-policy-considerations-for-covid-19-vaccine-rollout/

- Larson, H. J., Clarke, R. M., Jarrett, C., Eckersberger, E., Levine, Z., Schulz, W. S., & Paterson, P. (2018). Measuring trust in vaccination: A systematic review. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 14(7), 1599–1609. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1459252

- Latkin, C. A., Dayton, L., Yi, G., Konstantopoulos, A., & Boodram, B. (2021). Trust in a COVID-19 vaccine in the U.S.: A social-ecological perspective. Social Science & Medicine, 270, 113684. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113684

- Ledford, C. J. W., Cafferty, L. A., Moore, J. X., Roberts, C., Whisenant, E. B., Garcia Rychtarikova, A., & Seehusen, D. A. (2022). The dynamics of trust and communication in COVID-19 vaccine decision making: A qualitative inquiry. Journal of Health Communication, 27(1), 17–26. doi:10.1080/10810730.2022.2028943

- Marcelin, J. R., Swartz, T. H., Bernice, F., Berthaud, V., Christian, R., da Costa, C. … Abdul-Mutakabbir, J. C. (2021). & Infectious diseases society of America (IDSA) Inclusion, D., access, and equity taskforce, George counts interest group, and society of infectious diseases pharmacists (SIDP) diversity, equity and inclusion taskforce. Addressing and Inspiring Vaccine Confidence in Black, Indigenous, and People of Color During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 8(9), ofab417. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab417

- Marquez, C., Kerkhoff, A. D., Naso, J., Contreras, M. G., Diaz, E. C., Rojas, S. … Havlir, D. V. (2021). A multi-component, community-based strategy to facilitate COVID-19 vaccine uptake among latinx populations: From theory to practice. PloS One, 16(9), e0257111. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0257111

- Ndugga, N., Hill, L., Artiga, S., & Haldar, S. (2022, July 14). Latest data on COVID-19 vaccinations by race/ethnicity. KFF. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/latest-data-on-covid-19-vaccinations-by-race-ethnicity/

- NYC Health(2022).NYC Public Health Corps.https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/health/neighborhood-health/public-health-corps.page.

- Omari, A., Boone, K. D., Zhou, T., Lu, P. -J., Kriss, J. L., Hung, M. -C. … Singleton, J. A. (2022). Characteristics of the moveable middle: opportunities among adults open to COVID-19vaccination. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 64(5), 734–741. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2022.11.003

- Presidential COVID-19 health equity task force: final report and recommendations. (2021). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. https://www.minorityhealth.hhs.gov/assets/pdf/HETF_Report_508_102821_9am_508Team%20WIP11-compressed.pdf

- Ramachandran, S., Kusisto, L., & Honan, K. (2020, June 11). How New York’s coronavirus response made the pandemic worse. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-new-yorks-coronavirus-response-made-the-pandemic-worse-11591908426

- State of New York Executive Chamber Executive Order No. 202.17. (2020, April 15). https://www.governor.ny.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/EO_202.17.pdf

- Stout, M. E., Christy, S. M., Winger, J. G., Vadaparampil, S. T., & Mosher, C. E. (2020). Self-efficacy and HPV vaccine attitudes mediate the relationship between social norms and intentions to receive the HPV vaccine among college students. Journal of Community Health, 45(6), 1187–1195. doi:10.1007/s10900-020-00837-5

- Supporting Peers and Community Health Workers—NYC Health(2022).NYC Health.https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/providers/resources/supporting-peers-and-community-health-workers-in-their-roles.page.

- Suran, M. (2022). Why parents still hesitate to vaccinate their children against COVID-19. JAMA, 327(1), 23–25. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.21625

- Tan, S. B., deSouza, P., & Raifman, M. (2022). Structural racism and COVID-19 in the USA: A county-level empirical analysis. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 9(1), 236–246. doi:10.1007/s40615-020-00948-8

- Teasdale, C. A., Ratzan, S., Rauh, L., Lathan, H. S., Kimball, S., & El-Mohandes, A. (2022). COVID-19 vaccine coverage and hesitancy among New York city parents of children aged 5–11 years. American Journal of Public Health, 112(6), 931–936. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2022.306784

- Thompson, C. N., Baumgartner, J., Pichardo, C., Toro, B., Li, L., Arciuolo, R., & Fine, A. (2020). COVID-19 Outbreak—New York City, February 29–June 1, 2020. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(46), 1725–1729. doi:https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6946a2

- Vindrola-Padros, C., & Johnson, G. A. (2020). Rapid techniques in qualitative research: A critical review of the literature. Qualitative Health Research, 30(10), 1596–1604. doi:10.1177/1049732320921835

Appendix A

Interview Guide

Thank you again for your willingness to share your experiences with us in this interview. We’ll start with the consent form I sent you. I want to make sure that we have a chance to answer any questions you have.

Informed consent

Interviewer will have open: Informed Consent Document, IDI guide

Ask the participate to locate and open the Hello Sign document. Re-send if needed.

Review the Consent Form with the participant and answer any relevant questions. Screen share the consent form (zoomed in) so participants can read along as we review it.

Emphasize that the study is voluntary, and they can withdraw their participation at any time

Remind participants that the interview will be recorded, but everything they share will be confidential; all notes, recordings, and transcripts will use a study ID number, rather than their real name

Remind participants that they do not have to answer any questions that they don’t feel comfortable answering

Give the participant the opportunity to ask questions. Once all questions are answered, electronically sign the document together.

Prior to recording, change the participant’s Zoom name to their study ID number, using the following script:

“To protect your confidentiality, I am going to change your Zoom display name to your Participant ID number. For this interview, your number is [XX].”

Just a few reminders before we get started:

You are the expert on this topic and I want to hear whatever you have to say. This is about your thoughts and experiences. There are no right or wrong answers.

If any of my questions don’t make sense to you, please feel free to let me know.

Any questions before we start? Okay, I’m going to start the recorder now.

START RECORDING

Today is [date] and this is interview [Participant ID]

Opening Question:

1. I’d appreciate it if you could start by telling me a little bit about yourself.

[Aim: To give participants room to introduce themselves, their personal, cultural, social, professional contexts.]

Introductory Question:

How have you and your family been doing during the COVID-19 pandemic over the last two years?

How were your child’s experiences with remote schooling?

Did anyone in your family test positive for COVID?

[Aim: To inquire how the participant has experienced the COVID-19 pandemic as context for their thinking about vaccination.]

Transition Question:

2. Next, I want to transition into talking about the COVID-19 vaccine. What are your thoughts about the COVID-19 vaccine currently?

[Integrate reported experiences, emotions reported in the introductory question and how the vaccine has impacted their overall experience through the pandemic]

Key Questions:

When you first heard about the COVID-19 vaccine availability, what did you think? Can you walk me through your thinking about the vaccination from that point in time to present?

Possible probe: Has your perspective on your decision to be vaccinated or remain unvaccinated evolved over time? If so, what shifted your thinking?

Possible probe: Can you describe what you weighed and considered when deciding whether you would get vaccinated/remain unvaccinated?

As a parent of young child(ren), what did you think when you first heard about the COVID-19 vaccine for children 5–11? Can you walk me through your thinking about the vaccination from that point in time to present?

Possible probe: How firmly decided are you about the childhood COVID-19 vaccine for 5–11 year olds?

In your survey, you indicated that you were [undecided/somewhat likely] to vaccinate your child against COVID-19. Can you tell me more about this response?

Possible probe: What is influencing your thinking? What concerns do you have?

Possible probe: You mentioned that [“you don’t trust the vaccine/the vaccine seems sketchy/etc.”]- what are some of the reasons why it seems untrustworthy?

(Probe based on possible sources of mistrust: the medical system, the media, politicians)

Possible probe: Who have you talked to about vaccinating your 5–11 year old(s)? (Have you spoken with any medical professionals, like your child’s pediatrician, about childhood vaccination?)

Probe: What sources of information have been helpful to you?

Possible probe: How do you feel about childhood vaccinations in general? How is your thinking about COVID-19 vaccination similar to or different from your thinking about other childhood vaccinations?

(If different) what are some of the ways that it’s different?

How did you make your decision about other childhood vaccines? (Probe: what resources helped you make your decision? Sources of information? Did you speak with anyone while thinking through your decision?)

Do your children receive a flu shot? (Probe why or why not)

(If not discussed already) If there was a COVID-19 vaccine mandate for schools, what would your reaction be?

How do your children feel about the COVID-19 vaccine?

Possible probe: What kinds of conversations have you had with them about the COVID-19 vaccine?

Possible probe: What have you overheard your children say about the COVID-19 vaccine, if anything?

If you are hesitant about childhood COVID-19 vaccination, what might give you more confidence in choosing to vaccinate your 5–11 year old child(ren)?

What kinds of information would be helpful?

Is there anyone else you would like to talk to as you make your decision?

Add-on time permitting: [If parent also has a 12–18 year old child] Thinking now about your older child[ren], I’m curious about how you and they are thinking about COVID-19 vaccination for them. Can you tell me about this?

Structured Questions:

Now we’re going to transition into a few questions with shorter answers:

What is your current job and/or occupation?

What is the highest grade or year you completed in school?

The next question is about your income. Which of the following categories best describes your total household income last year, before taxes? Please include any income you and other family members may have received from jobs, public assistance, interest, or any other sources. Please stop me when I get to the right category.

Less than $10,000

$10,000 to $19,999

$20,000 to $29,999

$30,000 to $39,999

$40,000 to $49,999

$50,000 to $59,999

$60,000 to $69,999

$70,000 to $79,999

$80,000 to $89,999

$90,000 to $99,999

Over $100,000

What type of health insurance do you have?

Public (e.g. Medicaid or other)

Private

What is the zip code in which you currently live?

Closing Question:

1. Would you like to add any other comments, thoughts, or questions about your thoughts on childhood COVID-19 vaccines that we haven’t talked about yet?

Thank you!

At the end of the interview, thank the participant for sharing their thoughts

○ onfirm e-mail for the electronic gift card disbursement