Abstract

Normalizing mental health disorders in media communication can have a positive impact on the public by improving awareness. However, normalizing issues like anxiety could lead people to categorize normal anxiety as a disorder. In Study One, viewing social media posts that normalized anxiety resulted in a greater likelihood of self-diagnosis of anxiety disorder compared to social media posts that did not normalize it. This effect was through identification with and liking of the person featured in the social media post. In Study Two, those results were replicated. Additionally, we expected, but did not find, that normalizing anxiety had an impact on perceived stigma of anxiety disorders. Thus, at least in this case, normalization influenced self-diagnosis primarily through increasing identification with another person with anxiety, rather than decreasing stigma. Efforts to maximize positive impacts of normalizing disorders should examine unintended, potentially negative, consequences.

In recent years, there have been efforts to understand the influence of communication technology on mental health (Sadagheyani & Tatari, Citation2021), leading to advances in diagnosis and treatment (Abbott, Shirali, Haws, & Lack, Citation2017). Since mass media can often portray anxiety in stigmatized ways, there have been calls to normalize anxiety (e.g. Mellifont & Smith-Merry, Citation2015). Per the Integrative Model of Behavioral Prediction (Fishbein & Cappella, Citation2006), norms play an important role in health decisions. However, as discussed below, portraying anxiety disorders as commonplace could either help or harm social media users’ mental health.

Anxiety in-and-of itself is normal. However, an anxiety disorder involves excessive and intense fear about normal situations (Abbott, Shirali, Haws, & Lack, Citation2017). It may include sudden onsets of panic attacks and debilitating feelings of intense anxiety, causing difficulties doing daily tasks.

The prevalence of anxiety, particularly among college students, is concerning; a 2019 survey from the American College Health Association showed that 66.4% reported feeling “overwhelming anxiety” at least once during the academic year. Further, almost 10% of college students are being or have been treated for depression (Beiter et al., Citation2015), and mental illness is the leading cause of disability worldwide (Whiteford et al., Citation2015).

Normalizing issues like anxiety can have positive implications for public health. For example, normalizing mental health concerns for medical students led to increased help seeking (Martin et al., Citation2020). People with mental health disorders can share their stories on social media and share resources to educate a larger audience to normalize what can otherwise seem like an isolating health problem (Lawlor & Kirakowski, Citation2017).

On the other hand, overdiagnosis of anxiety disorders can be problematic (Lawrence, Rasinski, Yoon, & Curlin, Citation2015). People who spend excessive time reading about health problems online can develop cyberchondria, a condition in which frequent internet use results in excessive health concerns (Khan, Pandey, Cohl, & Gipp, Citation0000). Internet-assisted self-diagnosis can lead to misinformation, delayed treatment, low-efficacy, or dangerous self-treatment through recreational drugs (Charlton, Citation2005). Further, increased usage of social media has been linked to increased self-reported diagnosis of depression (Block et al., Citation2014).

Conceptual Framework

The Integrative Model of Behavioral Prediction (Fishbein & Cappella, Citation2006) posits that attitudes, norms, and efficacy interact with environmental and individual factors to influence behavior. The current study focuses primarily on norms. Norms are expected to be influenced by beliefs and perceived social approval of a behavior (Wang, Citation2013). An example of a descriptive norm could be “lots of people have anxiety.” Having the right referent group is vital to successful appeals. For example, identification and liking can be important in the influence of norms. Terry & Hogg propose that the main normative influence on our behavior comes from people we identify with in specific contexts, such as “other students” (Terry & Hogg, Citation1996). Supporting evidence includes research demonstrating that those who identify more strongly as “students” were more likely to have intentions to eat unhealthy foods when they believed that other students were doing the same (Louis, Davies, Smith, & Terry, Citation2007). Additionally, youth who more strongly identified with a peer group were more likely to have the same smoking status as that referent group (Schofield, Pattison, Hill, & Borland, Citation2001).

While substantial research has examined the role of norms in influencing behavior when people identify more strongly with the referent group (e.g. Rhodes & Ellithorpe, Citation2016), Rimal & Lapinski suggest that norms are also dynamic (Rimal & Lapinski, Citation2015). Accordingly, we ask if normative messages on social media (a person describing their anxiety disorder as “normal”) may cause participants to identify with the referent (the person who posted about their anxiety) more strongly and thus be more likely to classify their own anxiety as disordered.

Therefore, the main goal of this research is to examine the potential role of normalizing messages in identification and descriptive norms about anxiety and whether social media posts which normalize anxiety increase the likelihood of self-diagnosis of anxiety disorder.

Study One

The Integrative Model of Behavioral Prediction (Fishbein & Cappella, Citation2006) suggests that health behavior is primarily determined by attitudes, efficacy, norms, and ability when there are no environmental constraints. In this case of this study the behavior is reporting self-diagnosis in an anonymous setting, so no environmental constraints are expected. For some people, answering in the affirmative to a survey question about whether they think they have an anxiety disorder can be a significant behavior since recognizing excessive anxiety is important for health (see https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/how-to-help-someone-with-anxiety).

Normalization of Mental Health Conditions

Subjective norms refer to beliefs about what others think is appropriate, and descriptive norms refer to what other people do (Fishbein & Cappella, Citation2006). Social media posts relevant to anxiety can address both descriptive and subjective norms by depicting a person discussing their own anxiety in a casual way (increasing perception that other people have anxiety and that discussing it is appropriate). Similarly, May and Finch (Citation2009) defined normalization as deliberate social action that makes a topic routine in already existing structures of social life. Our conceptualization of normalization is, then, a sense that anxiety disorders are both common and socially appropriate to discuss.

Efforts to normalize anxiety can be seen in an example from 2002, under the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, a national address toward normalization, in which recommendations were made to address the poor state of the mental health delivery system in America (Stephan, Weist, Kataoka, Adelsheim, & Mills, Citation2007). Even popular songs can contain lyrics that may form a “social normalization” regarding openness about mental health struggles (Kresovich, Citation2022).

Given this, we expect that people who see social media posts that normalize anxiety are likely to consider anxiety disorders more common than those who see social media posts that do not normalize anxiety. In addition to survey measures, cognitive response items can provide valuable insight by asking participants to respond in writing with their first thoughts after viewing the stimulus materials (Watkins & Rush, Citation1983). In this case, it is likely that participants who see the normative versions of the posts would differ from those who see the non-normative versions in terms of whether they characterize anxiety as being normal.

H1: Participants who see the normalizing posts will be more likely than those who see the non-normalizing posts to rate anxiety disorders as more common on the two-item descriptive norm variable (H1a) and to mention in their cognitive response that anxiety is normal or common (H1b).

However, while this categorization can have some practical benefits in terms of help-seeking, it also has drawbacks when presented on social media. For example, the information that is shared online is not always monitored or credible (Rubin, Citation2019). This leads to common misconceptions, as well as a means of easy and cheap alternative treatment via the internet instead of a practicing health care professional. The dangers of self-diagnosis are evident in a study done among U.S. service members (Nevin, Citation2009), and unfortunately, due to the generality of symptoms that can be found online, the public can come to believe that they have a health problem or disorder that they may not (Hovenkamp-Hermelink et al., Citation2019).

When social identity is salient, people may match their thoughts and behaviors to a referent group (Abrams, Citation1992). In this case, the referent group is a group of similarly aged people on social media. Thus, exposure to a message that normalizes anxiety may inadvertently lead to a belief that one has a disorder. Yet to our knowledge, this has not been empirically tested.

Hypothesis 2: Participants who see the normalizing posts will be more likely than those who see the non-normalizing posts to report higher level of self-reported personal stress (H2a) and self-diagnosis with an anxiety disorder (H2b).

Identification and Liking

One mechanism we expect to drive this effect is identification with the author of the social media post. Identification (Cohen, Citation2001) is an empathetic reaction to a media personality. While identification is often conceptualized as the disappearance of the self to decrease distance between oneself and the person they are identifying with, like Kresovich (Citation2022), we focus on the perceived personal connection aspect of identification in which the audience does not need to know the person they are identifying with very well to make that connection with them. For example, Lewis (Citation2015) found that even in social media posts, identification with others moderated participants’ responses to a normative message about health and nutrition. Also, Mou and Shen (Citation2018) found that user generated social media posts with health messages in a personal story-style post increased positive identification with the post creator which increased behavioral intentions in line with the intent of the post.

Hypothesis 3: Identification will mediate effects of normalizing posts on self-reported anxiety(H3a) and self-diagnosis (H3b).

Like identification, viewers’ liking of people who post about anxiety on social media might influence how viewers interpret their own anxiety. Since people are less likely to identify with others they find to be socially unpopular (e.g. Ji, Citation2022), identification with people who post about their anxiety on social media is more likely to occur if the viewer likes the post creator. Seeing a social media post that features a photo of a person who is suffering from anxiety and making efforts to normalize it might be seen as “brave” or “admirable” by the public if they are supportive of such measures. Indeed, based on first impressions of others in social media, people tend to like those who are socially expressive and personal (Weisbuch, Ivcevic, & Ambady, Citation2009). Thus, we expect that normalization could lead the audience to have a more positive appraisal of the person in the social media post.

Hypothesis 4: Liking will mediate effects of normalizing posts on self-reported anxiety (H4a) and self-diagnosis (H4b).

However, we also expected to find a boundary effect regarding gender matching of the participants and the person featured in the social media posts. Women tend to consider themselves to be more like social media influencers when the influencers are also female, resulting in more positive brand attitude and post engagement (Hudders & De Jans, Citation2021). Likewise, when anxiety is normalized, people may be more likely to identify with the person featured in the post when they are gender matched.

H5: The mediating role of identification for the effects of normalizing posts on self-reported anxiety (H5a) and self-diagnosis of anxiety (H5b) will be moderated by the gender match between the social media post and participant.

Method

Design

This study employed a 2 (anxiety normalized or not normalized) x 2 (gender matched or not matched) experimental design. For the gender conditions, the stimuli pool included images of three different males or females. Therefore, each participant was exposed to one of 12 message stimuli.

Participants

There were 654 participants in this study coming from a sample of undergraduate students who were recruited in exchange for course credit; 69% female, 30.9% male, and 0.1% identified as nonbinary. Sixty-five percent identified as “White,” 8.1% as “Black,” 22% as “Asian” and 3.2% as “other race.” The average age was M = 20.61, SD = 4.04, and data was collected from June 2020 until October 2020.

Procedures

After reading through the consent form and agreeing to participate in this Institutional Review Board approved project (protocol number: 2020B0135) participants were asked about their general social media use. They were then shown an image of a social media post, with a 30-second timer to ensure they had ample time to read the post.

Stimuli

Images were created to resemble posts on the social media site, Instagram. The posts contained images of a person and text below the photos. To increase the stimulus sample pool, six different images of people were used. These images were purchased from Shutterstock and included three males and three females, all aged in their late teens or early 20s. Only one person was included in each image (per a typical “selfie” on Instagram) and the backgrounds were grassy (i.e. there were no other people or background items in the images aside from grassy nature). Thus, there were 12 versions in total (3 males, 3 females, normalized or not), all designed to be as similar as possible while still featuring different people. Text and hashtags accompanied each picture.

Normalizing Stimuli

“I wanted to share something personal with you guys today. I have anxiety, which, in simple terms, means I worry over things I shouldn’t. Anxiety can be manageable, and it’s possible to overcome it. I know that having anxiety is normal. So many people out there have anxiety, and I am one of them. If you experience anxiety too, please learn more at the website linked in my bio. #AnxietyIsNormal,” “#NormalizeAnxiety,” and “TalkToAFriend.”

Non-Normalizing Stimuli

“I wanted to share something personal with you guys today. I have been diagnosed with generalized anxiety, which is a serious mental health disorder. Anxiety can be manageable, and it’s possible to overcome it. But I know the anxiety I feel is beyond what most people experience; it is a serious mental health disorder. If you experience anxiety too, please learn more at the website linked in my bio. AnxietyIsADisorder,” “#AnxietyDisorderAwareness,” and “TalkToADoctor.”

In this way, both versions of the stimuli focused on awareness, the most common frame for mental health issues on social media sites like Twitter (Pavlova & Berkers, Citation2020). We also sought to address both descriptive and subjective norms (Fishbein & Cappella, Citation2006) in the normalized version by providing an example of someone with anxiety using clear hashtags such as “#AnxietyIsNormal.” Since normalization was the primary interest in the present study, other aspects of the integrated model of behavioral prediction, such as efficacy, were included but not manipulated.

Measures

Scaled items ranged from five-point scales to eleven-point scales. All scaled outcome variables were indexed by averaging after satisfactory exploratory factor analysis, with presents means, standard deviations, Cronbach’s alphas, and ranges of the measures. Items were given on a Likert-type scale with anchors of “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” unless noted otherwise.

Table 1. Measures from study one

Cognitive Responses

After viewing the social media ad, participants saw a cognitive response item in which they had up to one minute to type in any thoughts they had after seeing the ad. Specifically, the question was “Please spend up to one minute writing out any thoughts and feelings that came up while you were viewing the post.” Coders examined whether normalization was mentioned or not. Normalization was defined as using the words “normalize” or “common” or including something that indicated normalization without necessarily using those words. For example, “I think it helps if people know how common anxiety is” was coded as “normalized.” One of the authors coded all the cognitive response items, and another author coded 10% of them to check for inter-coder reliability. Krippendorff’s alphas (calculated with Hayes & Krippendorff’s, Citation2007 macro) ranged from .89 to .95.

Norms

Participants were asked two questions about descriptive norms: “In the United States, anxiety disorders are … ” and “At my university, anxiety disorders are … .” Responses ranged from “Very common” to “Not common.”

Personal Stress

Personal stress was measured with seven items such as “My level of stress is higher than most of my friends stress levels” and “My stress levels are higher than most college students.”

Identification

Identification was measured using an alteration of Cohen’s scale (Cohen, Citation2001), with items such as “While reading the post, I felt as if it was relevant to me” and “I was able to understand the post in a way similar to how someone with anxiety would.”

Liking

Liking the person featured in the social media post was assessed with items asking if the person seems “likable,” “similar to me,” “similar to someone I know,” and “like someone I would be friends with.”

Self-Reported Anxiety

A scale measuring anxiety included six items asking about participants’ level of being wound up, frightened, restless, and having worrying thoughts, butterflies in the stomach and panic. The response scale ranged from “Not At All” to “Most of the Time”.

Self-Diagnosis of Anxiety Disorder

Two items asked about participants’ beliefs that they have an anxiety disorder or will have one in the future, ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree”.

Data Analysis Strategy

We examined direct effects via independent samples t-tests for H1(a), H1(b), H2(a), H2(b) using SPSS version 26. For mediated effects, H3(a) and H3(b), H4(a) and H4(b), we used Model 4 from Hayes’s PROCESS macro, version 3 (Hayes, Citation2018). For H5, we used Hayes’s Model 7. See for correlations.

Table 2. Correlations from study one

Results

Regarding H1a, those who saw the post that normalized anxiety (M = 1.71, SD = 0.76) considered anxiety to be more common than those who saw posts that did not normalize anxiety (M = 1.58, SD = 0.65), t(650) = 1.60, p = .039. Additionally, for H1b, the cognitive response items were analyzed via content analysis in which posts were coded as either containing or not containing thoughts about normalization. When the social media posts normalized anxiety, participants were more likely to mention normalization in their cognitive response (25% did so) than when the posts did not normalize anxiety (16% mentioned normalization), χ2 (1, N = 653) = 7.992, p = .005.

As expected in H2a, people who saw the social media post that normalized anxiety (M = 2.0046, SD = .8122) were more likely to classify themselves as having an anxiety disorder than those who saw the social media post that did not normalize anxiety (M = 1.8465, SD = .7857), t (652), = −2.530, p = .012. However, no direct effects of normalized posts on personal stress was found (H2b), p = .196. Thus, while people who saw the normalized post did not report higher levels of anxiety, they were more likely to classify their anxiety as a disorder.

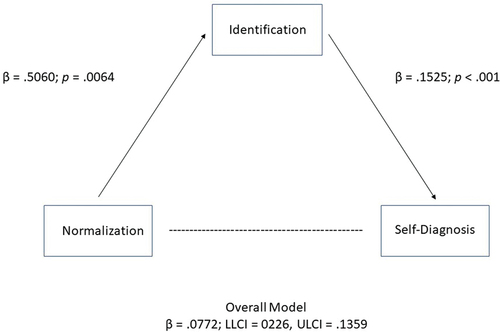

H3 examined identification as a possible explanatory mechanism for why anxiety normalization led to increased self-reported anxiety and self-diagnosis. Normalization did predict identification with the person featured in the post, p = .0064. See . Since normalization was coded “1” and the lack of normalization was coded as “0” and higher numbers on the identification scale meant stronger identification, the positive beta, B = .5060, indicates that normalization increased identification. Identification, in turn, predicted more likelihood of self-reported anxiety (H3a), p < .001, B = .1211 and self-diagnosing with anxiety (H3b), p < .001, B = .1525.The direct effect of normalization on self-diagnosis disappears when identification is added to the model (p = .1498), but the overall mediation model was significant, B = .0772, LLCI = .0226, ULCI = .1359. Likewise, the direct effect of normalization on self-reported anxiety disappears when identification is added to the model (p = .9088), but the overall mediation model was significant, B = .0622, LLCI = .0173, ULCI = .1103.

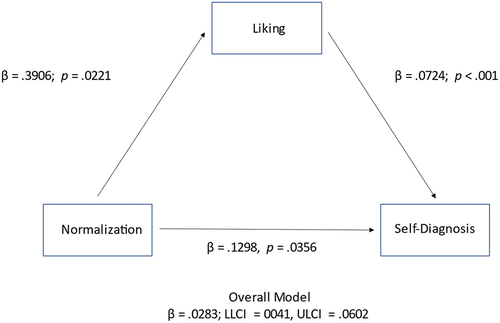

H4 predicted that liking for the person featured in the social media post would also serve as a mediator similar to identification. Indeed, people who saw the version of the post in which anxiety was normalized reported more liking (b = .3906, p = .0221), which in turn predicted self-diagnosis (B = .0724, p < .001) and self-reported anxiety (B = .0171, p = .0015). The direct effect of normalization on self-diagnosis remained significant (B = .1298, p = .0356), as was the overall model (B = .0283, LLCI = .0041, ULCI = .0602). The direct effect of normalized messages on self-reported anxiety was nonsignificant (p = .5415), but the indirect effect of normalized messages on self-reported anxiety through liking the person in the ad was supported (B = .0171, LLCI = .0014, ULCI = .0397). See .

H5, examining possible boundary conditions for the effect of normalization on self-diagnosis, predicted moderated mediation, but was not supported. People who were gender matched did not experience more identification with the person featured in the post (B = .2060, p = .4299). The interaction between normalization and gender matching was not significant (p = .0658). Similarly, gender matching did not directly influence the liking variable (p = .4499) nor did the interaction between gender matching and normalization (p = .1367).

Discussion

Normalizing mental health disorders, such as anxiety, can have positive implications, such as making people feel more comfortable seeking help (e.g. Martin et al., Citation2020). However, the models examined here provide evidence that when people see a social media post that normalizes anxiety, they are more likely to identify with the person in the post, and thus are more likely to consider themselves as having an anxiety disorder. There are concerns that people who self-diagnose an anxiety disorder may be led to misinformation that can have negative consequences. Indeed, internet-assisted self-diagnosis can lead to misinformation, delayed treatment, low-efficacy, or dangerous self-treatment through recreational drugs (Charlton, Citation2005).

While this impact of social media normalization of anxiety through identification is important, stigma is also an important variable to examine. Stigma includes negative stereotypes stemming from long-term prejudices and traditional negative associations for people with mental health disorders (Ociskova, Prasko, & Sedlackova, Citation2013). Historically, mental health disorders have been stigmatized, reducing treatment seeking (Schulze & Angermeyer, Citation2003). Anxiety has been particularly stigmatized resulting in fear of social disapproval, lowered self-esteem, and delayed treatment, which can increase mortality for patients with cardiac problems (Ociskova, Prasko, & Sedlackova, Citation2013).

To better understand how people are reacting to social media posts that normalize anxiety, it’s important that we also examine the impact these can have on stigma, which was not measured in Study One.

Study Two

Data from Study One indicate that normalizing anxiety on social media can cause viewers to identify more strongly with social media personalities who disclose their anxiety, and this identification can then lead to viewers to classify their own anxiety as disordered. To better understand the generalization of the results of Study One, we seek to replicate the following hypotheses with a new group of participants:

H1: Participants who view a social media post that normalizes anxiety will classify their own anxiety as a disorder more often than those who view a post that does not normalize anxiety.

H2: Posts that include normalization will result in increased self-diagnosis of an anxiety disorder through identification with the person featured in the social media post.

In addition to replicating the main results of Study One, we seek to better understand the role of stigma in relationship to normalization since mental health issues have long been stigmatized.

Stigma can be defined as a negative belief or attitude toward a group (Ledford, Lim, Namkoong, Chen, & Qin, Citation2021). Such negative beliefs might include a person being perceived as weak for experiencing mental health challenges (Love, Citation2018, as cited in; Parrott, Billings, Hakim, & Gentile, Citation2020). Anxiety disorders impact about one-third of American adults at some point in their lives (National Institutes of Mental Health, Citation2017), but remain stigmatized despite the prevalence (Corrigan, Citation2004). They may experience family members discouraging them from seeking treatment due to concerns about the stigma spreading (Ociskova, Prasko, & Sedlackova, Citation2013). Online stigma can be particularly concerning since people can be motivated to share information, including messages about stigmatized others, to create their own social bonding (Berger, Citation2014; Ledford, Lim, Namkoong, Chen, & Qin, Citation2021), which reinforces barriers to seeking treatment (Corrigan, Citation2004).

There have been some efforts on social media to destigmatize anxiety. For example, professional athletes such as DeMar DeRozan and Kevin Love have shared their experiences with mental health issues with fans to create a more normative environment (Parrott, Billings, Buzzelli, & Towery, Citation2021; Parrott, Billings, Hakim, & Gentile, Citation2020). Social media is a common outlet for discussing such issues since mainstream journalism doesn’t often provide a platform for people with mental illnesses to speak for themselves (Narin & Coverdale, Citation2005). However, it is unclear whether the positive reception of fans to these well-known athletes’ personal disclosure would also result from posts by unknown peers. Particularly with famous or well-liked people, their self-disclosure of mental health challenges can increase perceptions of how common mental health illnesses are, but they may also destigmatize the issues due to their reputation as being a well-liked individual.

Thus, it’s important to differentiate stigma and normalization conceptually. For example, in their research on chronic illness, Joachim and Acorn (Citation2001) argue that although stigma and normalization overlap (normalizing a condition may lead to it being destigmatized), examining the way these two cognitive mechanisms interact is important. Another example is that although cannabis use has become more normalized, it can remain stigmatized (Hathaway, Comeau, & Erickson, Citation2011). Weiste and colleagues discuss this overlap and call for efforts toward normalization and anti-stigma campaigns to be examined separately (Weiste, Stevanovic, Valkeapaa, Valkiaranta, & Lindholm, Citation2021). However, although the concepts are different, we expect some overlap given that an increased sense of normalcy may also work to destigmatize anxiety (i.e. if it’s not unusual, it’s not bad or deviant).

H3: Posts that include normalization will result in increased self-diagnosis of an anxiety disorder through decreased perception of stigma about anxiety.

Method

The design, procedures, and stimuli from Study One were used again in Study Two. The Skidmore Anxiety Scale on stigma was added.

Participants

There were 151 participants in this study (all were from the same university as Study One, but none participated in Study One), 55.6% female, 44.4% male. Regarding power, although power analyses are not generally recommended for mediation analyses (see page 141 of Hayes, Citation2018), about 53% of mediation studies have 151–200 participants (Fritz & MacKinnon, Citation2007), making the number of participants in this study average. Seventy-four percent identified as “white,” 7.3% as “Black,” 14% as “Asian” and 4% as “other race.” The average age was M = 20.0066, SD = 2.8035, and data was collected between November 2020 and April 2021.

Stigma

Seven items were included that asked what percentage participants believed for the following, rated on a five-point scale from 0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100%: “What percent of people with an anxiety disorder exaggerate their symptoms?” “What percentage of anxiety disorders do not require treatment to reduce symptoms?” “What percent of people with an anxiety disorder are too weak to overcome their symptoms?” “What percentage of anxiety disorders are nothing but everyday stress?” “What percentage of people with an anxiety disorder use their symptoms to attract attention?” “What percentage of anxiety disorders can be treated by changing one’s diet and exercise?” “What percentage of people with an anxiety disorder use their symptoms to avoid certain responsibilities?” A correlation matrix revealed multiple correlations over .3 and KMO and Bartlett’s test was significant. Two factors had eigenvalues great than one, with two of the seven items loading onto a factor together (both items asked about treatment). However, since these items also loaded onto the first factor and the Cronbach’s alpha would not be increased by deleting them (α = .803), all seven items were index together.

Data Analysis Strategy

The same analyses were used in Study Two as Study One. See for correlations.

Table 3. Correlations from study two

Results

H1 predicted a direct effect of normalized posts on self-diagnosis and was supported. Those who saw the version of the ads that were normalized (M = 2.0625, SD = .7869) were more likely to describe their anxiety as a “disorder” than those who saw the non-normalized versions (M = 1.7597, SD = .80545), t(147) = −2.318, p = .022. As in Study One, normalization did not have a direct impact on reports of actual anxiety levels but did impact whether participants considered their anxiety to be disordered.

H2 predicted that normalization would impact self-diagnosis through identification with the model and was again supported. Those who saw the normalized version had more identification (p = .0011), and identification in turn predicted self-diagnosis (p < .001). The overall model was supported B = .1641, LLCI = .0593, ULCI = .2899.

However, regarding H3, the hypothesis that normalization would decrease stigma (and thus increase self-diagnosis of disordered anxiety) was not supported. The stigma index did predict whether viewers considered their own anxiety disordered (p < .001, B = −.2796; of note, since higher numbers on the stigma index as associated with more perceived stigma, those with more perceived stigma were less likely to consider their own anxiety to be disordered). However, whether the version of the post they saw normalized anxiety or not did not impact their responses to the stigma items. Thus, both the direct effect of normalization on stigma (p = .0798) and the overall mediation model of normalization on self-classification through stigma (LLCI = −.0453, ULCI = .0246) failed to reach significance.

Discussion

As expected, versions of the social media posts that normalized anxiety led to increased likelihood that participants would consider their own anxiety to be disordered through identification with the person featured in the post. It’s important that we examine how efforts to normalize anxiety may have unintended consequences on social media users since many people who struggle with mental health are unlikely to seek help given the associated stigma and lack of understanding surrounding the issues (Chisholm et al., Citation2016), and discussion about mental health is increasingly taking place on social media (Naslund, Aschbrenner, Marsch, & Bartels, Citation2016). However, the relationship between normalization and stigma is not clear.

Previous research has found that college students who have a personal connection to music with a message about mental health issues have less stigma toward afflicted individuals (Kresovich, Citation2022). Thus, we expected that normalized versions of the social media post would likewise result in decreased stigma toward people suffering with anxiety. However, contrary to expectations, normalized versions of the post did not decrease perceived stigma. In fact, stigma toward people with anxiety was relatively low overall (M = 2.33, SD = .64 on a five-point indexed scale) and negatively correlated with self-diagnosis of anxiety disorder (p = .049, see ).

One possible explanation may be that young people simple do not feel much stigma toward others with anxiety. For example, Pavlova and Berkers (Citation2020) examined the framing of Twitter messages relevant to mental health and found that the “stigma frame” was not terribly common, while framing intended to raise awareness was more common. When mental health was stigmatized, it was often due to fear of violence, which may not be associated with anxiety as much as other mental health challenges.

Another possible explanation for our findings is that students are likely to classify their anxiety as disordered when they identify with a social media personality who discloses a personal story normalizing anxiety, but they may be inclined to distance themselves from such a diagnosis when they feel that anxiety is stigmatized. Evidence suggests that indeed people do prefer to distance themselves socially from stigmatized groups (Cano et al., Citation2020).

Limitations

In this study, only young adult white models were included in the stimuli creation. Although we did not find any effects for gender matching, it’s possible that other demographics, such as age and race, could influence the direct and indirect effects of social media posts on self-diagnosis. Similarly, other social media sites (in addition to our mock-Instagram posts) could be explored since social media sites vary in both features and users.

We also suggest that future research explore whether stigma causes people to feel reluctant to accept a medical diagnosis and under what conditions that is likely to occur. While this concept has been discussed by groups such as the National Alliance on Mental Illness (Ponte, Citation2021), and evidence suggests that stigma can play a role in delaying help seeking (Henderson, Evans-Lacko, & Thornicroft, Citation2013), there has not been much empirical research on the conditions under which patients may actively push back against a medical diagnosis due to stigma.

Finally, the messages in the current study led to self-diagnosis of anxiety disorders through identification with the person who posted on social media about having an anxiety disorder. Future research could examine whether there are conditions or message characteristics that might help participants empathize with (rather than identify with) people with anxiety disorders. This might be one way to try to normalize anxiety without leading to increases in self-diagnosis.

Conclusions

Generally, normalizing anxiety disorders can have positive outcomes for public health because it can increase the chances of people seeking help (e.g. Martin et al., Citation2020). For practical purposes, opinion leaders should be aware of the potential for backfire if normalization leads to an increase in self-diagnosis- as the data here show that people who saw social media posts seeking to normalize anxiety were more likely to classify their own anxiety as a disorder, through identification with the person featured in the social media post. We also caution health care professions not to assume that increased normalization will also decrease stigma related to mental health care. Rather, future research could help inform message design regarding mass media messages that increase normalization while also decreasing stigma without having a negative effect from participants self-diagnosing with an anxiety disorder.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbott, D., Shirali, Y., Haws, J. K., & Lack, C. W. (2017). Biobehavioral assessment of the anxiety disorders: Current progress and future directions. World Journal of Psychiatry, 7(3), 133–147. doi:10.5498/wjp.v7.i3.133

- Abrams, D. (1992). Processes of social identification. In G. M. Breakwell (Ed.), Social psychology of identity and the self-concept. Academic Press, Elsevier.

- Beiter, R., Nash, R., McCrady, M., Rhoades, D., Linscomb, M., Clarahan, M., & Sammut, S. (2015). The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 173, 90–96. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.054

- Berger, J. (2014). Word-of-mouth and interpersonal communication: An organizing framework and directions for future research. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 24(4), 586–607. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2014.05.002

- Block, M., Stern, D. B., Raman, K., Lee, S., Carey, J. … Breiter, H. C. (2014). The relationship between self-report of depression and media usage. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, (8). doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00712

- Cano, I., Best, D., Beckwith, M., Phillips, L. A., Hamilton, P., & Sloan, J. (2020). Stigma related to health conditions and offending behaviors: Social distance among students of health and social sciences. Stigma and Health, 5, 38–52. doi:10.1037/sah0000165

- Charlton, B. G. (2005). Self-management of psychiatric symptoms using over-the-counter (OTC) psychopharmacology: The S-DTM therapeutic model – self-diagnosis, self-treatment, self-monitoring. Medical Hypotheses, 65(5), 823–828. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2005.07.013

- Chisholm, D., Sweeny, K., Sheehan, P., Rasmussen, B., Smit, F., Cuijpers, P., & Saxena, S. (2016). Scaling-up treatment of depression and anxiety: A global return on investment analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(5), 415–424. doi:10.1016/s22150366(16)30024-4

- Cohen, J. (2001). Defining identification: A theoretical look at the identification of audiences with media character. Mass Communication & Society, 4(3), 245–264. doi:10.1207/S15327825MCS0403_01

- Corrigan, P. (2004). How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist, 59(7), 614–625. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614

- Fishbein, M., & Cappella, J. N. (2006). The role of theory in developing effective health communications. Journal of Communication, 56(suppl_1), 1–17. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00280.x

- Fritz, M. S., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 223–239. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x

- Hathaway, A. D., Comeau, N. C., & Erickson, P. G. (2011). Cannabis normalization and stigma: Contemporary practices of moral regulation. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 11(5), 451–469. doi:10.1177/1748895811415345

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Hayes, A. F., & Krippendorff, K. (2007). Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Communication Methods and Measures, 1(1), 77–89. doi:10.1080/19312450709336664

- Henderson, C., Evans-Lacko, S., & Thornicroft, G. (2013). Mental illness stigma, help seeking, and public health programs. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 777–780. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301056

- Hovenkamp-Hermelink, J., Veen, D. V. D., Voshaar, R. O., Batelaan, N., Penninx, B., Schoevers, R., & Riese, H. (2019). Anxiety sensitivity: Longitudinal stability and association with anxiety severity. Scientific Reports, 9(1). doi:10.1038/s41598-019-39931-7

- Hudders, L., & De Jans, S. (2021). Gender effects in influencer marketing: An experimental study on the efficacy of endorsements by same vs other-gender social media influencers on Instagram. International Journal of Advertising, 41(1), 128–149. doi:10.1080/02650487.2021.1997455

- Ji, Y. (2022). When distal group norms work: Testing effectiveness of distal norm-based messages as a function of desirability-motivated identification. Communication Studies, 73(1), 36–52. doi:10.1080/10510974.2021.1972018

- Joachim, G., & Acorn, S. (2001). Living with chronic illness: The interface of stigma and normalization. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 32, 37–48.

- Khan, A. W., Pandey, J., Cohl, H. S., & Gipp, B. Semantic preserving bijective mappings for expressions involving special functions between computer algebra systems and document preparation systems. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 71(3). doi:10.1108/AJIM-08-2021-0222

- Kresovich, A. (2022). The influence of pop songs referencing anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation on college students’ mental health empathy, stigma, and behavioral intentions. Health Communication, 37(5), 617–627. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1859724

- Lawlor, A., & Kirakowski, J. (2017). Claiming someone else's pain: A grounded theory analysis of online community participants experiences of Munchausen by internet. Computers in Human Behavior, 74, 101–111. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.070

- Lawrence, R. E., Rasinski, K. A., Yoon, J. D., & Curlin, F. A. (2015). Psychiatrists’ and primary care physicians’ beliefs about overtreatment of depression and anxiety. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 203(2), 120–125. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000247

- Ledford, V., Lim, J. R., Namkoong, K., Chen, J., & Qin, Y. (2021). The influence of stigmatizing messages on danger appraisal: Examining the model of stigma communication for opioid-related outcomes. Health Communication, 37(14), 1765–1777. doi:10.1080/10410236.2021.1920710

- Lewis, N. (2015). Examining normative influence in persuasive health messages: The moderating role of identification with other parents. International Journal of Communication, 9, 3000–3019.

- Louis, W., Davies, S., Smith, J., & Terry, D. (2007). Pizza and pop and the student identity: The role of referent group norms in healthy and unhealthy eating. The Journal of Social Psychology, 147(1), 57–74. doi:10.3200/SOCP.147.1.57-74

- Love, K. (2018). Everyone is going through something. The Players’ Tribune. https://www.theplayerstribune.com/en-us/articles/kevin-love-everyone-is-going-through-something

- Martin, A., Chilton, J., Paasche, C., Nabatkhorian, N., Gortler, H. … Neary, S. (2020). Shared living experiences by physicians have a positive impact on mental health attitudes and stigma among medical students: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 7, 2382120520968072. doi:10.1177/2382120520968072

- May, C., & Finch, T. (2009). Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: An outline of normalization process theory. Sociology, 43(3), 535–554. doi:10.1177/0038038509103208

- Mellifont, D., & Smith-Merry, J. (2015). The anxious times: An analysis of the representation of anxiety disorders in the Austrian newspaper, 2000-2015. Asia Pacific Media Educator, 25(2), 278–296. doi:10.1177/1326365X15604937

- Mou, Y., & Shen, F. Y. (2018). (Potential) patients like me: Testing the effects of user-generated health content on social media. Chinese Journal of Communication, 11(2), 186–201. doi:10.1080/17544750.2017.1386221

- Narin, R. G., & Coverdale, J. H. (2005). People never see us living well: An appraisal of the personal stories about mental illness in a prospective print media sample. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 39(4), 281–287. doi:10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01566.x

- Naslund, J. A., Aschbrenner, K. A., Marsch, L. A., & Bartels, S. J. (2016). The future of mental health care: Peer-to-peer support and social media. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 25(2), 113–122. doi:10.1017/S2045796015001067

- National Institutes of Mental Health. (2017). Any anxiety disorder. https://wwww.nihm.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml

- Nevin, R. L. (2009). Low validity of self-report in identifying recent mental health diagnosis among U.S. service members completing pre-deployment health assessment (PreDHA) and deployed to Afghanistan, 2007: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health, 9(1), 376. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-376

- Ociskova, M., Prasko, J., & Sedlackova, Z. (2013). Stigma and self-stigma in patients with anxiety disorders. Act Nerv Super Rediviva, 55, 12–18.

- Parrott, S., Billings, A. C., Buzzelli, N., & Towery, N. (2021). “We all go through it”: Media depictions of mental illness disclosures from star athletes DeMar DeRozan and Kevin love. Communication & Sport, 9(1), 33–54. doi:10.1177/2167479519852605

- Parrott, S., Billings, A. C., Hakim, S. D., & Gentile, P. (2020). From #endthestigma to #realman: Stigma-challenging social media responses to NBA players’ mental health disclosures. Communication Reports, 33(3), 148–160. doi:10.1080/08934215.2020.1811365

- Pavlova, A., & Berkers, P. (2020). “Mental health” as defined by twitter: Frames, emotions, stigma. Health Communication, 37(5), 637–647. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1862396

- Ponte, K. (2021). Overcoming stigma: Helping people accept their mental illness diagnosis. National Alliance on Mental Illness. https://www.nami.org/Blogs/NAMI-Blog/October-2021/Overcoming-Stigma-Helping-People-Accept-Their-Mental-Illness-Diagnoses

- Rhodes, N., & Ellithorpe, M. E. (2016). Laughing at risk: Sitcom laugh tracks communicate norms for behavior. Media Psychology, 19(3), 359–380. doi:10.1080/15213269.2015.1090908

- Rimal, R. N., & Lapinski, M. K. (2015). A re-explication of social norms, ten years later. Communication Theory, 25(4), 393–409. doi:10.1111/comt.12080

- Rubin, V. L. (2019). Disinformation and misinformation triangle. Journal of Documentation, 75(5), 1013–1034. doi:10.1108/jd-12-2018-0209

- Sadagheyani, H. E., & Tatari, F. (2021). Investigating the role of social media on mental health. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 25(1), 41–51. doi:10.1108/MHSI-06-2020-0039

- Schofield, P. E., Pattison, P. E., Hill, D. J., & Borland, R. (2001). The influence of group identification on the adoption of peer group smoking norms. Psychology & Health, 16(1), 1–16. doi:10.1080/08870440108405486

- Schulze, B., & Angermeyer, M. C. (2003). Subjective experiences of stigma: A focus group study of schizophrenic patients, their relatives, and mental health professionals. Social Science Medicine, 56(2), 299–312. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00028-X

- Stephan, S. H., Weist, M., Kataoka, S., Adelsheim, S., & Mills, C. (2007). Transformation of children’s mental health services: The role of school mental health. Psychiatric Services, 58(10), 1330–1338. doi:10.1176/ps.2007.58.10.1330

- Terry, D. J., & Hogg, M. A. (1996). Group norms and the attitude-behavior relationship: A role for group identification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(8), 776–793. doi:10.1177/0146167296228002

- Wang, X. (2013). Applying the integrative model of behavioral prediction and attitude functions in the context of social media use while viewing mediated sports. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1538–1545. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.01.031

- Watkins, J. T., & Rush, A. J. (1983). Cognitive response test. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 7(5), 425–435. doi:10.1007/BF01187170

- Weisbuch, M., Ivcevic, Z., & Ambady, N. (2009). On being liked on the web and in the “real world”: Consistency in first impressions across personal webpages and spontaneous behavior. Journal of Experimental and Social Psychology, 45(3), 573–576. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2008.12.009

- Weiste, E., Stevanovic, M., Valkeapaa, T., Valkiaranta, K., & Lindholm, C. (2021). Discussing mental health difficulties in a “diagnosis free zone”. Social Science & Medicine, 289, 114364. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114364

- Whiteford, H. A., Ferrari, A. J., Degenhardt, L., Feigin, V., Vos, T., & Forloni, G. (2015). The global burden of mental, neurological and substance use disorders: An analysis from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS One, 10(2), e0116820. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116820