Abstract

Marketers often advertise products high in sugar, fat or calories as healthy products. With this potentially misleading information, they can influence eating decisions with negative consequences for human health. Consumers need the ability to uncover misleading food advertising. However, individuals’ perceived knowledge and their actual objective abilities often drift apart – a phenomenon which has come to be known as the Dunning-Kruger Effect. Thus, this study set out to uncover the phenomenon’s potential existence in health communication, more precisely in the area of food and media literacy. In a quantitative survey representative of the Austrian population (n = 1000) the Dunning-Kruger Effect (DKE) could be detected: Individuals who were most knowledgeable underestimated their food and media literacy, but – on the positive side – they acted as opinion leaders. Individuals who were least knowledgeable about advertising strategies used to market an unhealthy product as healthy and about the actual nutrition score of the advertised product were most likely to overestimate their own food and media literacy. Worryingly, further concerning consequences emerged, especially for least knowledgeable individuals. The study’s results provide important implications for public health campaigns.

Research increasingly emphasizes social media’s role in the spread of misinformation in various health areas, also related to nutrition (Wang, McKee, Torbica, & Stuckler, Citation2019). Misleading information can also be used to gain strategic advantages, for example in advertising (Southwell, Thorson, & Sheble, Citation2018). Deficits in legal regulations still allow food companies to deceive customers, often advertising and selling products high in sugar as healthy (Foodwatch, Citation2018). Marketing products as healthy seems to be advantageous for companies, as consumers associate food products applying nutritional and health claims with healthiness (Aschemann-Witzel & Hamm, Citation2010) and if products are perceived to be healthy, purchase intentions rise too (Hwang, Lee, & Lin, Citation2016). The application of nutrition claims might also trigger harmful consequences for consumers’ health, leading to the consumption of more foods and higher calorie intakes, thus, contributing to obesity (Oostenbach, Slits, Robinson, & Sacks, Citation2019), which has nearly tripled worldwide since 1975 (WHO, Citation2021). Food ads can influence dietary choices negatively. For example, the consumption of energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods and drinks rises with positive perceptions of, and trust in, food advertisements (Thai, Serrano, Yaroch, Nebeling, & Oh, Citation2017) and the use of meat imagery in fast food advertising strongly enhances meat consumption (e.g. Ellithorpe et al., Citation2022).

Being armed with critical thinking skills regarding food ads can help individuals resist making unhealthy food choices (Ha et al., Citation2020). Media and food literacy might be important as media literacy provides people with critical thinking skills to “distinguish truthful media-based information from unhealthy or deceptive information” (Austin & Pinkleton, Citation2016, p. 175). Media literacy has been defined as “ability to access, analyze, evaluate, create, and act using all forms of media” (National Association for Media Literacy Education, Citation2021), whereas food literacy refers to “the idea of proficiency in food related skills and knowledge”(Truman, Lane, & Elliott, Citation2017, p. 365) and can also include food and health choices (Truman et al., Citation2017).Footnote1

Previous findings support the relevance of media literacy, for example, in promoting engagement in protective health behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic (Austin, Austin, Willoughby, Amram, & Domgaard, Citation2021) and fact-checking behavior in relation to health information (Lee & Ramazan, Citation2021). Austin, Austin, French, and Cohen (Citation2018) highlight the importance of also strengthening individuals’ media literacy in the nutrition context to mitigate the negative effects of unrealistic food marketing.

However, there is a risk that media and food literacy could be seriously compromised. Kruger and Dunning (Citation1999) discovered that those people who, in fact, display the lowest knowledge are those who overestimate their actual abilities most. In contrast, people showing actual high knowledge often underestimate their abilities, which points to a mismatch between actual and perceived abilities – a phenomenon known as the Dunning-Kruger Effect (DKE). People’s confidence in their own knowledge can become a problem, if their knowledge is incorrect (Freiling, Citation2019) and interventions to foster media literacy may be ineffective among those individuals who would need training in media literacy most (Gross & Latham, Citation2012). Individuals with the lowest actual skills are unlikely to seek help for skills which they believe they have, since they are highly confident about their skills (Gross & Latham, Citation2012; Sivakumar, Hanoch, Barnes, & Federman, Citation2016).

To the best of the authors’ knowledge research on the DKE’s presence in health communication and in particular among food and media literacy is still missing. Thus, the present study aims at empirically detecting the DKE’s existence in health communication in the context of misleading advertising on a quantitative and large-scale level. We use a representative sample (n = 1000) for the Austrian population to explore its potential threatening effect on people’s food and media literacy in the context of evaluating food advertising critically to identify misleading information here. Our study also follows previous suggestions from the field of information literacy (Gross & Latham, Citation2012) to investigate flawed self-assessments among different sub-populations and, more precisely, for the population at large – here for the Austrian population – thereby moving beyond a student sample. The present study emphasizes the urgency of dealing with misleading information distributed by food ads and, simultaneously, provides important implications for public health campaigns and policy makers to counteract the DKE’s effect. The central aim of this study is thus to answer the following research question: Does the DKE exist in the context of misleading food advertisements and is it relevant to health communication due to affecting users’ self- perceptions of (a) being able to report the actual health score of food portrayed in ads (food literacy) and (b) being able to detect advertising strategies used to deceive them (media literacy)?

Innovative aspects of our study are that both health-related food and media literacy are analyzed simultaneously as both are needed to detect misleading advertising. Moreover, our study analyzes several potential consequences related to the DKE.

Previous Research on the DKE

Since Kruger and Dunning’s (Citation1999) publication, the DKE has been discovered in various fields, for example, in sports coaching (Sullivan, Ragogna, & Dithurbide, Citation2019), in the area of egalitarianism (West & Eaton, Citation2019), wine knowledge (Aqueveque, Citation2018), or information literacy (Gross & Latham, Citation2012). While individuals having highest knowledge underestimated their abilities, individuals having lowest knowledge in a domain overestimated their abilities. Especially in the field of information literacy, this effect seems to be highly problematic since acquiring information literacy skills will become especially important in a society where more and more information is available via different types of media (Gross & Latham, Citation2012). Motta, Callaghan, and Sylvester. (Citation2018) highlighted the DKE’s consequences regarding vaccine policies. Individuals with the least knowledge about autism and its potential link to vaccines, regarded themselves as even more knowledgeable than medical experts and were also less convinced by mandatory implementations of vaccination policies. The findings on the DKE of Motta et al. (Citation2018) in the health area suggest potential negative effects on people’s health, highlighting the urgency of dealing with the DKE. Recent research (Choi, Northup, & Reid, Citation2021; Sivakumar et al., Citation2016) indicates the importance of distinguishing between actual and subjective expertise in the area of health literacy as well. Compared to those showing lower health literacy (measured as actual knowledge), more highly health literate people were more likely to understand nutrition information. Being more health conscious (subjective expertise) did not guarantee higher actual knowledge about food ads advertising unhealthy food (Choi et al., Citation2021). As recommended (Choi et al., Citation2021), we also extend these findings using a different claim (“Protein and Lower Carb”) and food item (chocolate cereal bar) in the misleading ad stimulus applied in this study. Similarly, Sivakumar et al. (Citation2016) also found that individuals with lower levels of health literacy rated their Medicare knowledge as sufficient, when, in fact, their actual Medicare knowledge was low. Neither study (Choi et al., Citation2021; Sivakumar et al., Citation2016) analyzed the DKE explicitly, nor did they analyze food and media literacy. Thus, transferring the DKE to health communication, we hypothesize:

H1:

H1: Individuals who are least knowledgeable about (a) the actual nutrition score of food products and (b) ad strategies used in food ads, will overestimate their (a) food and (b) media literacy.

H2:

H2: Individuals who are most knowledgeable about (a) the actual nutrition score of food products and (b) ad strategies used in food ads, will underestimate both their (a) food and (b) media literacy.

The DKE’s Potential Consequences

Our study extends previous research by also exploring the DKE’s potential consequences on important advertising evaluation variables like skepticism toward advertising, ad evaluation, and purchase intention as well as individual variables like involvement with a healthy diet, opinion leadership, and social media usage.

Advertising Evaluation Variables and Involvement with a Healthy Diet

In this study, we refer to skepticism toward advertising in general as “the tendency toward disbelief of advertising claims” (Obermiller & Spangenberg, Citation1998, p. 160).Footnote2 Actual knowledge about nutrition might be linked to consumers’ skepticism toward ads. Consumers scoring high on nutrition knowledge were more skeptical toward health claims. Those consumers who showed higher levels of skepticism toward health claims were also less likely to rely on health claims when deciding which products to buy (Tan & Tan, Citation2007). By contrast, people who indicated to have less knowledge about nutrition were less skeptical of health claims (Mitra, Hastak, Ringold, & Levy, Citation2019). However, people with low levels of skepticism might not evaluate ads more favorably (Koinig, Diehl, & Mueller, Citation2018). We also want to investigate, if people with lowest knowledge about nutrition and persuasive ad strategies evaluate/like the misleading ad differently compared to individuals with highest knowledge. People with lowest knowledge might also have a higher purchase intention toward the advertised product. Choi et al. (Citation2021) showed that individuals with lower health literacy were more likely to purchase unhealthy food advertised with a nutrient-content claim for lower fat compared to individuals with higher health literacy.

Another relevant construct is involvement. Highly involved individuals ascribe special importance to certain objects (Zaichkowsky, Citation1985), based on personal needs, values and interests.Footnote3+Footnote4 Compared to those individuals with lowest involvement with a healthy diet, individuals showing highest involvement with a healthy diet might also show higher knowledge about the actual nutrition score of products and ad strategies used in food ads, given that higher involvement with products also contributes to higher product knowledge (Liang, Citation2012). Thus, individuals who ascribe special relevance to a healthy diet (show higher involvement with a healthy diet) might have higher nutrition knowledge, compared to less involved individuals, who are less interested in a healthy diet. Given these initial considerations, we aim to answer the following questions to uncover potential consequences of the DKE:

RQ1:

RQ1: Do those individuals who are least knowledgeable about the actual nutrition score of products and ad strategies used in food ads have (a) a lower skepticism toward advertising, (b) a lower involvement with a healthy diet, (c) a more favorable ad evaluation (ad liking), and (d) a higher purchase intention for the advertised product than those who are most knowledgeable?

Opinion Leadership and Social Media Usage

People have the ability to influence other people’s attitudes and behavioral intentions (Ho et al., Citation2020; Jung, Shim, Jin, & Khang, Citation2016; Onofrei, Filieri, & Kennedy, Citation2022). Following Rodgers and Cartano (Citation1962), there are individuals “who exert an unequal amount of influence on the decision of others” whom they call “opinion leaders” (p. 435). Insights from Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, Citation1999, Citation2001) suggest a bidirectional relationship between personal, environmental and behavioral factors determining each other. Human learning is influenced, either consciously or unconsciously, by observing the behavior of other people, and this is also true for electronic mass media (Bandura, Citation1999). People imitate the behavior of opinion leaders (Kim & Dearing, Citation2016). Also, in the health sector, followers value opinion leaders’ views on health issues. Opinion leaders are gaining importance, especially given today’s health-related information overload caused by a plethora of communication channels (Kim & Dearing, Citation2016). As individuals often place high trust in them and their knowledge, opinion leaders can either protect others from disinformation or aggravate disinformation effects (Dubois, Minaeian, Paquet-Labelle, & Beaudry, Citation2020). Consequently, there might be a serious problem if those people are opinion leaders who know least about the actual healthiness of advertised foods (regarding e.g., sugar/fat content) and deceptive advertising practices in food advertising. They may share their incorrect knowledge with the people placing high trust in them and their expertise in a misleading manner, thus reinforcing the DKE. Moreover, if low-knowledge individuals are also active social media users, they may spread their flawed knowledge further on social media, as active social media users tend to share or post contents on social networking sites (Li, Citation2016), causing concerns about the quality of health information (Zhao & Zhang, Citation2017). This would mean that less knowledgeable individuals could pose a particularly high risk to other individuals, as there might be the danger that they reinforce the DKE. Thus, we also want to answer the following questions:

RQ2:

RQ2: Are those individuals who are least knowledgeable about the actual nutrition score of products and ad strategies used in food ads more likely to be opinion leaders than individuals with the highest knowledge?

RQ3:

RQ3: Are those individuals who are least knowledgeable about the actual nutrition score of products and ad strategies more active or passive social media users than individuals with the highest knowledge?

Method

To investigate the hypotheses and research questions, an online survey was conducted with a representative sample for the Austrian population. The survey was conducted with the support of the Gallup International Association (https://www.gallup.at/de/home/).

Applied Stimulus

For the present study, a fictitious ad was developed, based on which participants were invited to answer questions (stimulus available upon request). This ad – its design and the depicted product – was based on an existing food ad that has previously been criticized by the consumer rights organization Foodwatch (Foodwatch, Citationn.d.). Modifying real-world food ads for research purposes has also been practiced previously to enhance external validity (e.g., Choi, Paek, & Whitehill King, Citation2012; Choi & Reid, Citation2015). The stimulus depicted a chocolate cereal bar containing a lot of sugar and fat that is misleadingly advertised as being healthy by using the textual claims “Protein” and “Lower Carb” and the visual element of a slim blue silhouette in the background.

Procedure, Sample and Measurement

A qualitative pretest with n = 6 participants (66.6% female; age: M = 42.00 years, SD = 11.92) ensured the realistic design of the fictitious stimulus and the questionnaire’s comprehensibility. We followed a collaborative and iterative procedure for translation based on Douglas and Craig (Citation2007) as most of the scales used were translated from English into German. To counteract common method bias we followed suggestions by MacKenzie and Podsakoff (Citation2012).

For the main study, participants were recruited via the Gallup’s ISO certified online panel (Gallup Institut, Citation2022, p. 3). In total, n = 1000 people from the Austrian population, which is a representative sample, participated in the study (51.1% female, 49,7% male, 0.2% diverse; age: M = 47.98 years, SD = 17.25). shows an overview of participants’ sociodemographic characteristics. Participants received credit points as compensation.

All measures and items used in the questionnaire (including reliability estimates) are shown in . Unless otherwise indicated, all scales are seven-point Likert scales with the endpoints “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” At the beginning of the questionnaire, demographic data were collected, participants were thanked for their participation and informed about the aim of the study, the procedure, and the importance of their participation, and they were assured of the anonymous data collection. They were told that the purpose of the survey is to evaluate the effects of advertisements for food products. Following previous research (e.g., McMahon, Stoll, & Linthicum, Citation2020; Sullivan et al., Citation2019; West & Eaton, Citation2019), this study applied self-assessment measures (perceived food/media literacy) and an objective knowledge test to detect the DKE and to uncover whether people’s actual knowledge about food products and applied advertising strategies corresponded to their self-views. Following the self-assessment measures, participants were presented with the fictitious advertising stimulus which served as a basis for the knowledge test (announced as quiz to participants). presents the objective knowledge test. Participants were thanked again for their participation and the survey ended with a debriefing. Data were analyzed with IBM SPSS Version 28. Confirmatory factor analyses were performed using IBM SPSS AMOS Version 28.

Results

The objective knowledge test included questions measuring people’s actual food and media knowledge. Therefore also the self-assessment measures (food literacy and media literacy scales) were combined to form one variable. To correctly evaluate a food ad, both food and media literacy are needed simultaneously. A sum score was calculated for the 19 food and media literacy scale items (13 items measuring subjective food literacy and 6 items measuring subjective media literacy). Given that “7” was the highest possible score participants could indicate on the food and media literacy scales, in total, participants could reach 133 (19 multiplied by 7) points displaying their own perceived food and media literacy. Respondents showed a mean self-assessment score of 88.62 (SD = 19.40) for food and media literacy out of 133 points. In the objective knowledge test, their scores ranged from 4 to 18 (M = 10.36, SD = 2.43), out of a total of 21 achievable points.

In our research we followed a similar approach for data analysis to detect the DKE as researchers have used previously. Based on the participants’ performance in the objective test, they are grouped into quartiles (e.g., McMahon et al., Citation2020; Sullivan et al., Citation2019; West & Eaton, Citation2019). In our study, we conducted a quartiles analysis with SPSS 28, which resulted in the groups as reported in .

Table 1. Means and standard deviations for each group’s actual ability (=food and media knowledge) and self-assessment (=food and media literacy)

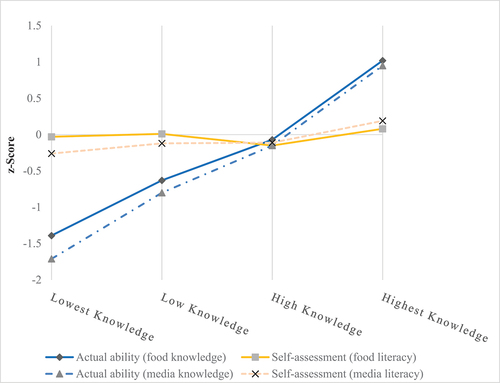

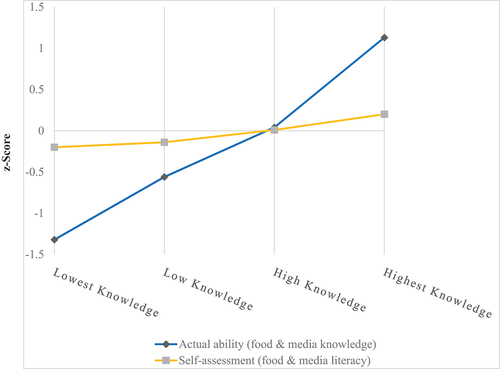

Paired sample t-tests were performed in the groups to check for the difference in mean scores between actual ability (food and media knowledge) and self-assessment (food and media literacy). Actual ability and self-assessment were measured using different scales. Hence, Z scores were calculated to interpret the results. Our results revealed that the “lowest-knowledge” group showed significantly higher self-assessment scores (food and media literacy) (Mz-score =-.20, SD = 1.09) than actual ability (food and media knowledge) (Mz-score=-1.32, SD = 0.41) (t(231)=-14.89, p < .001, d=-.98), thus supporting H1(a) and H1(b)Footnote5. Also, in the “low-knowledge” group, participants’ self-assessment scores (Mz-score=-.14, SD = 1.02) were significantly higher than their actual ability scores (Mz-score=-.56, SD=.00) (t(138)=-4.81, p < .001, d=-.41). In the “high-knowledge” group no significant difference emerged between self-assessment (Mz-score=.01, SD=.98) and actual ability (Mz-score=.04, SD=.21) (t(300)=.66, p = .51, d=.04). In contrast, the “highest-knowledge” group’s self-assessment scores (Mz-score=.20, SD=.91) were significantly lower than their actual ability (Mz-score = 1.13, SD=.50) (t(327) = 16.50, p < .001, d=.91), thus also supporting H2(a) and H2(b)5. shows a summary of the results, which confirm the existence of the DKE for food and media literacy. To support our findings, we also analyzed the DKE separately for food literacy/food knowledge and media literacy/media knowledge. We could confirm the DKE separately for food literacy/food knowledge and media literacy/media knowledge, further supporting H1(a+b) and H2(a+b).Footnote6

Figure 1. Differences between actual ability (food & media knowledge) and self-assessment (food & media literacy) per quartile.

Next, one-way ANOVAs were conducted to address RQs 1–3. For the ANOVAs, we defined 1) the quartilesFootnote7 as independent variable and 2) the variables: skepticism toward advertising, involvement with a healthy diet, ad evaluation (ad liking), purchase intention, opinion leadership subscales connectivity/persuasiveness/mavenness, and active and passive media usage as dependent variables. Comparisons were made among all four knowledge groups. presents the mean values and standard deviations for the variables across groups. Post-hoc comparisons were consulted and the LSD test was interpreted for all variables. depicts the post-hoc test results and significant/non-significant differences related to all groups. shows the results of a correlation analysis between all variables.

Table 2. Means and standard deviations across groups

To answer RQ1, focusing on ad (effectiveness)-related variables and involvement, the results of the ANOVAs indicated that there are significant differences between the groups for skepticism toward advertising, F(3, 995) = 4.46, p=.004; purchase intention, F(3, 995) = 3.99, p=.008; and involvement with a healthy diet, Welch’sFootnote8 F(3, 448.82) = 7.89, p < .001. In the mean comparison tests, no significant differences emerged between the groups regarding ad evaluation, F(3, 995)=.72, p=.539. Post-hoc comparisons (LSD test) showed that the “lowest-knowledge” group scored significantly lower on skepticism toward advertising (M = 4.47, SD = 1.42) compared to the “highest-knowledge” group (M = 4.89, SD = 1.32, p < .001) indicating that the “lowest-knowledge” group is less skeptical (RQ1a). Furthermore, the “lowest-knowledge” group scored significantly lower on involvement with a healthy diet (M = 4.88, SD = 1.54) compared to the “highest-knowledge” group (M = 5.43, SD = 1.19, p < .001), indicating that the “lowest-knowledge” group has a lower involvement (RQ1b). The “lowest-knowledge” group scored significantly higher on purchase intention (M = 3.38, SD = 1.75) compared to the “highest-knowledge” group (M = 2.89, SD = 1.58, p < .001), suggesting that the “lowest-knowledge” group is more likely to purchase the product (RQ1d). For ad evaluation, no significant differences emerged between the “lowest-knowledge” group and the “highest-knowledge” group (RQ1c).

Moreover, we wanted to analyze if the members of the “lowest-knowledge” group are opinion leaders (RQ2). The ANOVA’s results showed significant differences between the four knowledge groups for the subscale persuasiveness, F(3, 995) = 3.74, p = .011, but no significant differences for the subscales connectivity, F(3, 995) = 1.66, p = .17, and mavenness, F(3, 995) = 2.21, p = .09. Post-hoc comparisons (LSD test) showed that for persuasiveness, the mean scores for the “lowest-knowledge” group were significantly lower (M = 4.38, SD = 1.15) compared to the “highest-knowledge” group (M = 4.66, SD = 1.12, p = .005). For mavenness, the “lowest-knowledge” group’s scores were also significantly lower (M = 3.93, SD = 1.37) compared to the “highest-knowledge” group (M = 4.19, SD = 1.24, p = .023). For connectivity, no significant differences emerged between all four groups. Interestingly, those who show the lowest knowledge are not more likely to be opinion leaders. It seems that those who are highly knowledgeable are more likely to persuade others and be consulted by others for information. Thus, individuals who are least knowledgeable about nutrition and ad strategies in food ads are not opinion leaders (RQ2).

Finally, when exploring RQ3 relating to media usage, in the mean comparison tests, no significant differences emerged between the groups regarding active media usage, F(3, 995) = 1.83, p = .140 and passive media usage, F(3, 995)=.73, p = .533. Post-hoc comparisons (LSD test) revealed that the “lowest-knowledge” group scored significantly higher on active media usage (M = 2.86, SD = 1.59) compared to the “highest-knowledge” group (M = 2.60, SD = 1.47, p = .045), suggesting a more active use of social media in the “lowest-knowledge” group compared to the “highest-knowledge” group. For passive media usage, no significant differences emerged between the “lowest-knowledge” group and the “highest-knowledge” group (RQ3).

Discussion and Implications

This study set out to explore whether food and media literacy might be affected by the Dunning-Kruger effect (Kruger & Dunning, Citation1999), when evaluating potentially misleading food advertisements. The study’s results show the presence of the DKE in the area of food and media literacy. Those individuals who were least knowledgeable about the potentially misleading advertising strategies used to market an unhealthy product as healthy and the actual nutrition score of an advertised cereal bar were most likely to overestimate their own food and media literacy. In contrast, those individuals who were most knowledgeable underestimated their food and media literacy. These results are in line with previous research that has detected this effect across a variety of domains (e.g., Aqueveque, Citation2018; Gross & Latham, Citation2012; Motta et al., Citation2018; Sullivan et al., Citation2019; West & Eaton, Citation2019), thereby extending previous findings and identifying the effect’s presence among food and media literacy in a health communication context.

As an important theoretical contribution, we also support the previously stated concern (Choi et al., Citation2021) that there is a mismatch between subjective and objective expertise when evaluating misleading food ads – in the present study on a large-scale level and by investigating reactions to a different product (chocolate cereal bar) and a different nutrient-content claim (Protein/Lower Carb). Our findings also provide important theoretical contributions in light of the “health halo effect” (Choi, Yoo, Hyun Baek, Reid, & Macias, Citation2013; Choi et al., Citation2021), where recipients maintain cognitive consistency of the positive aspects emphasized in health and nutrition claims and are consequently more likely to overlook the unhealthy components in the advertised product. Our study suggests that the health halo effect might be less present among individuals who have highest food- and media-related knowledge, since they are less likely to buy the advertised product compared to those with lowest knowledge.

In line with the study by Heiss, Naderer, and Matthes (Citation2021), our study suggests that people face difficulties in identifying healthwashed and potentially misleading ads. We outline an important additional aspect that deserves further consideration. Participants who were least knowledgeable about misleading food ads overestimated their competences in relation to food and media literacy and were actually not aware of their inability. According to Kruger and Dunning (Citation1999), those people who lack knowledge “suffer a dual burden.” Adding to their problem of drawing incorrect conclusions about their own abilities, their limited knowledge in a domain prevents them from realizing their own incompetence (Kruger & Dunning, Citation1999, p. 1132). The latter aspect bears important implications especially for health communication efforts.

Boosting people’s knowledge about misleading food ads and the DKE is crucial. Campaigns should create awareness not only of deceptive ads but also of the DKE’s existence. People should be made aware of the phenomenon and get informed that their self-assessment might be flawed to make them subsequently more attentive and receptive to validated knowledge communicated by, for example, health authorities. Such interventions, to help people with lowest knowledge levels, are crucial, since we were able to show that consumers with the lowest abilities but with high confidence in their abilities are most vulnerable regarding potentially misleading food ads, as they are less skeptical and more willing to buy the product without realizing the potentially negative effects of the product. However, health authorities should use complementary strategies in addition to increasing knowledge (e.g., develop tools assisting individuals in detecting trustworthy information sources) (Austin, Austin, Borah, Domgaard, & McPherson, Citation2023), given that high knowledge often does not automatically translate into desired nutrition behavior (Larsen, Citation2015; O’Brien & Davies, Citation2007).Footnote9

Additionally, food has recently been described as “a protagonist of the posting activity on social networks” (Ventura, Cavaliere, & Iannò, Citation2021, p. 674). Our study’s results showed that especially low-knowledge individuals are more likely to be active users of social networking sites. This finding may indicate that they could spread their incorrect knowledge more easily via social media channels. These results deliver cause for concern because they suggest that the DKE may be reinforced by the least knowledgeable group, but the results regarding opinion leaders paint a different, more optimistic picture.

Interestingly, our results suggest that it is not individuals with the lowest knowledge that are more likely to be opinion leaders but those with the highest knowledge. People who are most knowledgeable about food ingredients and misleading advertising tactics are most likely to persuade and be consulted by others for information. This finding aligns with Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, Citation1999, Citation2001), suggesting that people use opinion leaders and people from their surroundings to acquire information. Our result is promising as it suggests that high-knowledge individuals can pass on their correct knowledge to others and thus positively influence other people’s knowledge. If low-knowledge individuals are reluctant to change their self-views, it may be opinion leaders who have the power to persuade them to change their self-perceptions and abilities and assist them to use media more effectively. Public health campaigns, which should use social media channels, could then recruit opinion leaders who create awareness for the DKE’s existence among low-knowledge individuals and simultaneously provide them with correct knowledge about misleading food advertising tactics, with positive health effects. Social media influencers and campaigns appear to be especially promising as low-knowledge individuals use them a lot. As low-knowledge individuals also have a lower involvement toward a healthy diet, these campaigns could try to increase their involvement and thus interest in nutrition-related health information. Targeted marketing efforts might provide an efficient means to select opinion leaders who enjoy trust among different age groups.

Our results also lead to important implications for policy makers seeking to enforce stricter governmental regulations. Our study results highlight the importance of enforcing stricter laws on advertising unhealthy food items, since consumers’ self-assessment to detect misleading food ads are flawed and inaccurate. We thus suggest, related to regulatory implications, to make the Nutri-Score nutrition label mandatory in Austria and other countries, as it enables consumers to more easily identify the actual nutritional quality of food products (Egnell et al., Citation2020). Also, the IARC has called for the Nutri-Score’s wide-spread use in Europe and beyond (IARC, Citation2021). In Austria, companies that would be willing to use the Nutri-Score on their products voluntarily are, by law, not even allowed to do so (Foodwatch, Citation2020). Our study’s results emphasize the need that companies use the Nutri-Score as it also provides marketers with advantages. For example, purchase intentions for healthy products can be increased and even if unhealthy products display the Nutri-Score, marketers can show consumers that they want to be transparent and care about their health (De Temmerman, Heeremans, Slabbinck, & Vermeir, Citation2021). To protect especially individuals with low knowledge about food and media tactics, marketers should urgently consider using the Nutri-Score on their product packaging.

Limitations and Future Research

Moving beyond our contribution, we want to mention some limitations of our study, which provide directions for future research. In a first step, we could detect the DKE across food and media literacy in the context of misleading food ads, suggesting the importance of considering the DKE also in health communication research. Future research might want to test the relationships between these variables in the context of food and media literacy using structural equation modeling (SEM). This analysis replicated the traditional DKE analysis strategy of MANOVAs on samples split into quartiles. It was not an experiment and used a single message, however, limiting its ability to detect effects. Regression/SEM analysis could uncover associations of overconfidence with outcomes such as social media use. To test the robustness of our findings, experimental studies could be conducted that manipulate certain message characteristics in the food ad (e.g., colors, high vs. low information, ad complexity). Follow-up studies could also test how further individual difference variables, not investigated in this study, might have affected the DKE (e.g., gender, age, health status, product affinity, attitude toward advertising in general). Future research might also conduct qualitative interviews to uncover the DKE using additional research methods or longitudinal studies, as our study is a cross-sectional study.

We analyzed the impact of the DKE on several variables. In this context, additional variables might play a role, e.g., Austin et al. (Citation2021) found that, next to knowledge, variables like people’s expectancies of the results when performing health-related behaviors, willingness to perform the behaviors and their self-efficacy are important precursors of health-related behaviors.Footnote10 Future research is needed to investigate and test these additional variables as well.

We focused on the affective elements of skepticism, but there are also logic-based elements (Austin et al., Citation2002) and skepticism has also been considered as an outcome of critical thinking (Austin, Muldrow, & Austin, Citation2016). Future research may want to investigate these important aspects of skepticism. The same applies to our measurement of involvement. We focused on the cognitive component. Given that involvement also has an affective component (Zaichkowsky, Citation1994), it would be important to investigate if and how affective involvement with a healthy diet is related to actual knowledge about food and advertising strategies. Finally, it would be interesting to extend our research to other countries and product categories.

Ethical Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Belmont Report. Our study was a non-interventional survey study that only collected de-identified data, where ethical approval from an institutional review board is not required under European law. It was a study with human subjects that presents no greater than minimal risk to subjects. The study meets the criteria of the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The completion of the survey was considered as informed consent.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gallup International Association for their support in the data collection process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data available on request from the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Our focus is on media and food literacy. Information and health literacy are related concepts. To avoid confusion, we distinguish these two concepts as well.

Media literacy also shares similarities with information literacy, though some differences remain. The focus of information literacy is on the access to texts/information and barriers/enablers in this regard, whereas media literacy research focuses more on the critical analysis of information (Livingstone, Van Couvering, & Thumim, Citation2008), therefore we focus on media literacy. A related concept to media literacy and food literacy is health literacy. Health literacy has been defined as: “The degree to which individuals can obtain, process, understand, and communicate about health-related information needed to make informed health decisions” (Berkman, Davis, & McCormack, Citation2010, p. 16). In this vein, media literacy skills are also especially important when acquiring information related to health and for rejecting misinformation in this regard (Austin et al., Citation2021). Food literacy is more specific and more closely related to the evaluation of the information provided in the food advertisement than health literacy, which is why we use food literacy.

2 Skepticism has been suggested to include logic-based and affective elements which promote a more thoughtful processing of messages (Austin et al., Citation2002). Obermiller and Spangenberg’s definition of skepticism (Citation1998) aligns with affective elements that “should include trust, defined as positive and negative beliefs about the honesty of an information source” (Austin et al., Citation2002, p. 161), compared with logic-based elements that focus on realism and “the degree to which information in a message corresponds to an individuals’ view of social reality” (Austin et al., Citation2002, p. 161).

3 Zaichkowsky’s definition of involvement (Citation1985) refers to both affective and cognitive involvement (Zaichkowsky, Citation1994). In the present paper we focus on investigating the cognitive aspect of involvement.

4 Whenever we refer to “involvement with a healthy diet” in our study, we mean “cognitive involvement with a healthy diet”.

5 Findings are based on the combined scores of food and media literacy (self-assessment) as well as food and media knowledge (actual ability).

6 To provide further support for our findings, we also analyzed the DKE separately for food literacy (self-assessment)/food knowledge (actual ability) and media literacy (self-assessment)/media knowledge (actual ability). We were able to confirm the DKE separately for food literacy/food knowledge and media literacy/media knowledge, further supporting H1(a+b) and H2(a+b). In the objective knowledge test (measuring actual abilities), twelve questions tested 1) food knowledge and nine questions measured 2) media knowledge. Hence, for 1) food knowledge, participants could reach a maximum of twelve points and for 2) media knowledge nine points. We again generated quartiles and grouped participants into quartiles based on their scores reached for each of the two variables (food/media knowledge) separately in SPSS 28 (see for an overview of the groups). Paired samples’ t-tests revealed a similar picture. The “lowest-knowledge” group showed significantly higher self-assessment scores (food literacy) (Mz-score=-.03, SD=1.08) than actual ability (food knowledge) (Mz-score=-1.39, SD=.35) (t(180)=-16.83, p<.001, d=-1.25), thus providing support to H1(a). The same picture could be found for media literacy. The “lowest-knowledge” group’s self-assessment scores (media literacy) (Mz-score=-.26, SD=.96) were significantly higher than their actual ability (media knowledge) (Mz-score=-1.71, SD=.34) (t(104)=-14.50, p<.001, d=-1.41), supporting H1(b). In contrast, yet as expected, the “highest-knowledge” group’s self-assessment scores (food literacy) (Mz-score=.08, SD=.92) were significantly lower than their actual ability (food knowledge) (Mz-score=1.02, SD=.57) (t(397)=17.05, p<.001, d=.86), thus also supporting H2(a). Their self-assessment scores (media literacy) (Mz-score=.19, SD=.97) were also significantly lower than their actual ability (media knowledge) (Mz-score=.95, SD=.58) (t(423)=14.46, p<.001, d=.70), again lending support to H2(b). shows a summary of the results.

7 For this analysis, we used the quartiles where we grouped participants into four groups based on their overall score on the objective test measuring both food and media knowledge (as reported in ).

8 Variances were not equal only for cognitive involvement with a healthy diet. Therefore, the Welch test was interpreted.

9 Based on our study’s findings, the “highest-knowledge” group scored significantly lower on purchase intention (M=2.89, SD=1.58) compared to the “lowest-knowledge” group (M=3.38, SD=1.75, p<.001). This lower purchase intention suggests that the “highest knowledge group” is less likely to purchase an unhealthy advertised product thus benefitting their health. Thus, higher knowledge might help to protect against purchasing unhealthy food products. However, of course, in the present study we did not assess actual behavior, but behavioral intentions. Most of the measures we used are self-assessments (with the exception of objective knowledge), which are, of course, essential for determining the DKE, as the focus is on flawed self-assessments. We measured behavioral intentions, yet future research and in particular longitudinal studies could also investigate actual behavior.

10 As suggested by previous studies (e.g., Larsen, Citation2015; O’Brien & Davies, Citation2007), there is a distinction between knowledge/actual ability and willingness to apply the knowledge. Future research might investigate factors that intervene between knowing that something/an action would be healthier and factors such as social mechanisms and societal surroundings (Larsen, Citation2015), fear of missing out, convenience, or fatigue which can prevent people from taking the healthier route.

References

- Aqueveque, C. (2018). Ignorant experts and erudite novices: Exploring the Dunning-Kruger effect in wine consumers. Food Quality and Preference, 65, 181–184. doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2017.12.007

- Aschemann-Witzel, J., & Hamm, U. (2010). Do consumers prefer foods with nutrition and health claims? Results of a purchase simulation. Journal of Marketing Communications, 16(1–2), 47–58. doi:10.1080/13527260903342746

- Austin, E. W., Austin, B. W., Borah, P., Domgaard, S., & McPherson, S. (2023). How media literacy, trust of experts and flu vaccine behaviors associated with COVID-19 vaccine intentions. American Journal of Health Promotion, 37(4), 464–470. doi:10.1177/08901171221132750

- Austin, E. W., Austin, B. W., French, F., & Cohen, M. A. (2018). The effects of a nutrition media literacy intervention on parents’ and youths’ communication about food. Journal of Health Communication, 23(2), 190–199. doi:10.1080/10810730.2018.1423649

- Austin, E. W., Austin, B. W., Willoughby, J. F., Amram, O., & Domgaard, S. (2021). How media literacy and science media literacy predicted the adoption of protective behaviors amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Health Communication, 26(4), 239–252. doi:10.1080/10810730.2021.1899345

- Austin, E. W., Miller, A. C., Silva, J., Guerra, P., Geisler, N. … Kuechle, B. (2002). The effects of increased cognitive involvement on college students’ interpretations of magazine advertisements for alcohol. Communication Research, 29(2), 155–179. doi:10.1177/0093650202029002003

- Austin, E. W., Muldrow, A., & Austin, B. W. (2016). Examining how media literacy and personality factors predict skepticism toward alcohol advertising. Journal of Health Communication, 21(5), 600–609. doi:10.1080/10810730.2016.1153761

- Austin, E. W., & Pinkleton, B. E. (2016). The viability of media literacy in reducing the influence of misleading media messages on young people’s decision-making concerning alcohol, tobacco, and other substances. Current Addiction Reports, 3(2), 175–181. doi:10.1007/s40429-016-0100-4

- Austin, E. W., Pinkleton, B. E., Chen, Y.-C., & Austin, B. W. (2015). Processing of sexual media messages improves due to media literacy effects on perceived message desirability. Mass Communication and Society, 18(4), 399–421. doi:10.1080/15205436.2014.1001909

- Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 2(1), 21–41. doi:10.1111/1467-839X.00024

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychology, 3(3), 265–299. doi:10.1207/S1532785XMEP0303_03

- Beer-Borst, S. (2017, October). Questionnaires applied in the project “healthful & tasty: Sure!” NRP69 salt consumption. Switzerland: Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, University of Bern. https://boris.unibe.ch/106460/8/Beer-Borst%20NRP69SaltQuestionnairesSources%202017_corrected.pdf

- Berkman, N. D., Davis, T. C., & McCormack, L. (2010). Health literacy: What is it? Journal of Health Communication, 15(S2), 9–19. doi:10.1080/10810730.2010.499985

- Boster, F. J., Kotowski, M. R., Andrews, K. R., & Serota, K. (2011). Identifying influence: Development and validation of the connectivity, persuasiveness, and maven scales. Journal of Communication, 61(1), 178–196. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01531.x

- Bredahl, L. (2001). Determinants of consumer attitudes and purchase intentions with regard to genetically modified food – results of a cross-national survey. Journal of Consumer Policy, 24(1), 23–61. doi:10.1023/A:1010950406128

- Choi, H., Northup, T., & Reid, L. N. (2021). How health consciousness and health literacy influence evaluative responses to nutrient-content claimed messaging for an unhealthy food. Journal of Health Communication, 26(5), 350–359. doi:10.1080/10810730.2021.1946217

- Choi, H., Paek, H.-J., & Whitehill King, K. (2012). Are nutrient-content claims always effective? Match-up effects between product type and claim type in food advertising. International Journal of Advertising, 31(2), 421–443. doi:10.2501/IJA-31-2-421-443

- Choi, H., & Reid, L. N. (2015). Differential impact of message appeals, food healthiness, and poverty status on evaluative responses to nutrient-content claimed food advertisements. Journal of Health Communication, 20(11), 1355–1365. doi:10.1080/10810730.2015.1018630

- Choi, H., Yoo, K., Hyun Baek, T., Reid, L. N., & Macias, W. (2013). Presence and effects of health and nutrition-related (HNR) claims with benefit-seeking and risk-avoidance appeals in female-orientated magazine food advertisements. International Journal of Advertising, 32(4), 587–616. doi:10.2501/IJA-32-4-587-616

- De Temmerman, J., Heeremans, E., Slabbinck, H., & Vermeir, I. (2021). The impact of the nutri-score nutrition label on perceived healthiness and purchase intentions. Appetite, 157, 104995. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2020.104995

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung. (n.d.) Salzgehalte verschiedener Lebensmittel [ Salt content of different foods]. https://www.dge-sh.de/salzgehalt.html

- Diehl, S., Terlutter, R., & Mueller, B. (2016). Doing good matters to consumers: The effectiveness of humane oriented CSR appeals in cross-cultural standardized advertising campaigns. International Journal of Advertising, 35(4), 730–757. doi:10.1080/02650487.2015.1077606

- Douglas, S. P., & Craig, C. S. (2007). Collaborative and iterative translation: An alternative approach to back translation. Journal of International Marketing, 15(1), 30–43. doi:10.1509/jimk.15.1.030

- Dubois, E., Minaeian, S., Paquet-Labelle, A., & Beaudry, S. (2020). Who to trust on social media: How opinion leaders and seekers avoid disinformation and echo chambers. Social Media & Society, 6(2), 1–13. doi:10.1177/2056305120913993

- Egnell, M., Galan, P., Farpour-Lambert, N. J., Talati, Z., Pettigrew, S., Hercberg, S., & Julia, C. (2020). Compared to other front-of-pack nutrition labels, the Nutri-Score emerged as the most efficient to inform Swiss consumers on the nutritional quality of food products. PLoS ONE, 15(2), e0228179. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228179

- Ellithorpe, M. E., Zeldes, G., Hall, E. D., Chavez, M., Takahashi, B., Bleakley, A., & Plasencia, J. (2022). I’m lovin’ It: How fast food advertising influences meat-eating preferences. Journal of Health Communication, 27(3), 141–151. doi:10.1080/10810730.2022.2068701

- Foodwatch. (2018, November 12). Rechtlos im Supermarkt. Gesundheitsgefahren, Täuschung und Betrug: Warum das Lebensmittelrecht Verbraucherinnen und Verbraucher nicht ausreichend schützt. [ Being without rights in the supermarket. Health risks, deception, and fraud: Why the food law does not protect consumers properly]. https://www.foodwatch.org/fileadmin/Themen/Lebensmittelpolitik/Dateien/2018-11-12_Report_Rechtlos_im_Supermarkt.pdf

- Foodwatch. (2020, November 25). Nutri-Score: Fragen & Antworten. [Nutri-Score: Questions & Answers] Foodwatch. Retrieved from 2022, December 9. https://www.foodwatch.org/at/informieren/lebensmittelampel-nutri-score/nutri-score-die-wichtigsten-fragen-antworten/

- Foodwatch.(n.d.). Factsheet. https://www.foodwatch.org/fileadmin/-DE/Themen/Windbeutel/Dokumente/Factsheet_03_Schwartau_final.pdf

- Freiling, I. (2019). Detecting misinformation in online social networks: A think-aloud study on user strategies. Studies in Communication and Media, 8(4), 471–496. doi:10.5771/2192-4007-2019-4-471

- Gallup Institut. (2022, March). Intelligent Insights. Introducing Ourselves. Gallup Institut. Retrieved from 2022, March 31. https://gallup.at/fileadmin/documents/PDF/GALLUP_Institutspraesentation_English_t.pdf

- Gross, M., & Latham, D. (2012). What’s skill got to do with it? Information literacy skills and self-views of ability among first-year college students. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(3), 574–583. doi:10.1002/asi.21681

- Ha, O.-R., Killian, H. J., Davis, A. M., Lim, S.-L., Bruce, J.-M., & Bruce, A. S. (2020). Promoting resilience to food commercials decreases susceptibility to unhealthy food decision-making. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 599663. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.599663

- Heiss, R., Naderer, B., & Matthes, J. (2021). Healthwashing in high-sugar food advertising: The effect of prior information on healthwashing perceptions in Austria. Health Promotion International, 36(4), 1029–1038. doi:10.1093/heapro/daaa086

- Ho, S. S., Goh, T. J., Chuah, A. S. F., Leung, Y. W., Bekalu, M. A., & Viswanath, K. (2020). Past debates, fresh impact on nano-enabled food: A multigroup comparison of presumed media influence model based on spillover effects of attitude toward genetically modified food. Journal of Communication, 70(4), 598–621. doi:10.1093/joc/jqaa019

- Hwang, J., Lee, K., & Lin, T.-N. (2016). Ingredient labeling and health claims influencing consumer perceptions, purchase intentions, and willingness to pay. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 19(4), 352–367. doi:10.1080/15378020.2016.1181507

- IARC. (2021, September 1). Nutri-Score: Harmonized and Mandatory Front-Of-Pack Nutrition Label Urgently Needed at the European Union Level and Beyond [Press release]. https://www.iarc.who.int/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/pr301_E.pdf

- Jung, J., Shim, S. W., Jin, H. S., & Khang, H. (2016). Factors affecting attitudes and behavioural intention towards social networking advertising: A case of facebook users in South Korea. International Journal of Advertising, 35(2), 248–265. doi:10.1080/02650487.2015.1014777

- Kim, D. K., & Dearing, J. W. (2016). Opinion leader identification. In D. K. Kim & J. W. Dearing (Eds.), Health communication research measures (pp. 77–86). New York et al.: Peter Lang.

- Koinig, I., Diehl, S., & Mueller, B. (2018). Exploring antecedents of attitudes and skepticism towards pharmaceutical advertising and inter-attitudinal and inter-skepticism consistency on three levels: An international study. International Journal of Advertising, 37(5), 718–748. doi:10.1080/02650487.2018.1498653

- Krause, C. G., Beer-Borst, S., Sommerhalder, K., Hayoz, S., & Abel, T. (2018). A short food literacy questionnaire (SFLQ) for adults: Findings from a Swiss validation study. Appetite, 120, 275–280. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2017.08.039

- Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it. How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

- Larsen, M. H. (2015). Nutritional advice from George Orwell. Exploring the social mechanisms behind the overconsumption of unhealthy foods by people with low socio-economic status. Appetite, 91, 150–156. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2015.04.001

- Lee, D. K. L., & Ramazan, O. (2021). Fact checking of health information: The effect of media literacy, metacognition and health information exposure. Journal of Health Communication, 26(7), 491–500. doi:10.1080/10810730.2021.1955312

- Li, Z. (2016). Psychological empowerment on social media: Who are the empowered users? Public Relations Review, 42(1), 49–59. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.09.001

- Liang, Y.-P. (2012). The relationship between consumer product involvement, product knowledge and impulsive buying behavior. Procedia – Social & Behavioral Sciences, 57(9), 325–330. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.1193

- Livingstone, S., Van Couvering, E., & Thumim, N. (2008). Converging traditions of research on media and information literacies. In J. Coiro, M. Knobel, C. Lankshear, & D. J. Leu (Eds.), Handbook of research on new literacies (pp. 103–132). New York: Routledge.

- Lyons, B. A., Montgomery, J. M., Guess, A. M., Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2021). Overconfidence in news judgement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(23). e2019527118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2019527118

- MacKenzie, S. B., & Lutz, R. J. (1989). An empirical examination of the structural antecedents of attitude toward the ad in an advertising pretesting context. Journal of Marketing, 53(2), 48–65. doi:10.1177/002224298905300204

- MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, P. M. (2012). Common method bias in marketing: Causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies. Journal of Retailing, 88(4), 542–555. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2012.08.001

- McMahon, C., Stoll, B., & Linthicum, M. (2020). Perceived versus actual autism knowledge in the general population. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 71, 101499. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2019.101499

- Mitra, A., Hastak, M., Ringold, D. J., & Levy, A. S. (2019). Consumer skepticism of claims in food ads vs. on food labels: An exploration of differences and antecedents. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 53(4), 1443–1455. doi:10.1111/joca.12237

- Motta, M., Callaghan, T., & Sylvester, S. (2018). Knowing less but presuming more: Dunning-Kruger effects and the endorsement of anti-vaccine policy attitudes. Social Science & Medicine, 211, 274–281. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.06.032

- National Association for Media Literacy Education. (2021). Media Literacy! National Association for Media Literacy Education. Retrieved from 2022, November 22. https://namle.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Media-Literacy-One-Sheet.pdf

- Obermiller, C., & Spangenberg, E. R. (1998). Development of a scale to measure consumer skepticism toward advertising. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 7(2), 159–186. doi:10.1207/s15327663jcp0702_03

- O’Brien, G., & Davies, M. (2007). Nutrition knowledge and body mass index. Health Education Research, 22(4), 571–575. doi:10.1093/her/cyl119

- Onofrei, G., Filieri, R., & Kennedy, L. (2022). Social media interactions, purchase intention, and behavioural engagement: The mediating role of source and content factors. Journal of Business Research, 142, 100–112. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.12.031

- Oostenbach, L. H., Slits, E., Robinson, E., & Sacks, G. (2019). Systematic review of the impact of nutrition claims related to fat, sugar and energy content on food choices and energy intake. BMC Public Health, 19, 1296. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7622-3

- Pagani, M., & Mirabello, A. (2011). The influence of personal and social-interactive engagement in social TV web sites. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 16(2), 41–67. doi:10.2753/JEC1086-4415160203

- Parmenter, K., & Wardle, J. (1999). Development of a general nutrition knowledge questionnaire for adults. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 53, 298–308. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600726

- Pinkleton, B. E., & Austin, E. W. (2016). Media literacy. In D. K. Kim & J. W. Dearing (Eds.), Health communication research measures (pp. 65–76). New York et al.: Peter Lang.

- Rodgers, E. M., & Cartano, D. G. (1962). Methods of measuring opinion leadership. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 26(3), 435–441. doi:10.1086/267118

- Schaefer, S. D., Terlutter, R., & Diehl, S. (2019). Is my company really doing good? Factors influencing employees’ evaluation of the authenticity of their company’s corporate social responsibility engagement. Journal of Business Research, 101, 128–143. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.03.030

- Schaefer, S. D., Terlutter, R., & Diehl, S. (2020). Talking about CSR matters: Employees’ perception of and reaction to their company’s CSR communication in four different CSR domains. International Journal of Advertising, 39(2), 191–212. doi:10.1080/02650487.2019.1593736

- Schulze-Lohmann, P. (2012). Ballaststoffe. Grundlagen – präventives Potenzial – Empfehlungen für die Lebensmittelauswahl [Fibre. Basics – Preventive potential – Recommendations for food selection]. Ernährungs Umschau, 7, 408–417. https://www.ernaehrungs-umschau.de/fileadmin/Ernaehrungs-Umschau/pdfs/pdf_2012/07_12/EU07_2012_408_417.qxd.pdf

- Sivakumar, H., Hanoch, Y., Barnes, A. J., & Federman, A. D. (2016). Cognition, health literacy, and actual and perceived medicare knowledge among inner-city medicare beneficiaries. Journal of Health Communication, 21(2), 155–163. doi:10.1080/10810730.2016.1193921

- Southwell, B. G., Thorson, E. A., & Sheble, L. (2018). Introduction: Misinformation among mass audiences as a focus for inquiry. In B. G. Southwell, E. A. Thorson, & L. Sheble (Eds.), Misinformation and mass audiences (pp. 1–12). University of Texas Press. doi:10.7560/314555-002

- Sullivan, P. J., Ragogna, M., & Dithurbide, L. (2019). An investigation into the Dunning–Kruger effect in sport coaching. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17(6), 591–599. doi:10.1080/1612197X.2018.1444079

- Tan, S.-J., & Tan, K.-L. (2007). Antecedents and consequences of skepticism toward health claims: An empirical investigation of Singaporean consumers. Journal of Marketing Communications, 13(1), 59–82. doi:10.1080/13527260600963711

- Thai, C. L., Serrano, K. J., Yaroch, A. L., Nebeling, L., & Oh, A. (2017). Perceptions of food advertising and association with consumption of energy-dense nutrient-poor foods among adolescents in the United States: Results from a national survey. Journal of Health Communication, 22(8), 638–646. doi:10.1080/10810730.2017.1339145

- Truman, E., Lane, D., & Elliott, C. (2017). Defining food literacy: A scoping review. Appetite, 116, 365–371. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2017.05.007

- Ventura, V., Cavaliere, A., & Iannò, B. (2021). #socialfood: Virtuous or vicious? A systematic review. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 110, 674–686. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2021.02.018

- Wang, Y., McKee, M., Torbica, A., & Stuckler, D. (2019). Systematic literature review on the spread of health-related misinformation on social media. Social Science & Medicine, 240, 112552. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112552

- West, K., & Eaton, A. A. (2019). Prejudiced and unaware of it: Evidence for the Dunning-Kruger model in the domains of racism and sexism. Personality and Individual Differences, 146, 111–119. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2019.03.047

- WHO. (2021, June 9). Obesity and Overweight. Retrieved from 2022, March 28. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

- Zaichkowsky, J. L. (1985). Measuring the involvement construct. The Journal of Consumer Research, 12(3), 341–352. doi:10.1086/208520

- Zaichkowsky, J. L. (1994). The personal involvement inventory: Reduction, revision, and application to advertising. Journal of Advertising, 23(4), 59–70. doi:10.1080/00913367.1943.10673459

- Zhao, Y., & Zhang, J. (2017). Consumer health information seeking in social media: A literature review. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 34(4), 268–283. doi:10.1111/hir.12192

Appendix

Table A1. Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

Table A2. Applied measures – items with means, standard deviations; reliability estimates: confirmatory factor analyses results, cronbach alpha

Table A3. Objective knowledge test with correct answers (marked in bold)

Table A4. Results of the Post-hoc tests: for all four groups

Table A5. Descriptive statistics and correlations for study variables

Table A6. Number of participants per group, grouping of participants based on scores on objective test, means and standard deviations for each group’s: actual ability (=food knowledge) and self-assessment (=food literacy); actual ability (media knowledge) and self-assessment (=media literacy)