Abstract

In Togo, family planning (FP) use remains low; only 24.1% of married woman ages 15 to 49 use modern FP. The West Africa Breakthrough ACTION (WABA) project developed the Confiance Totale radio campaign, which used a Saturation+ approach to encourage FP use. This study presents the results of an evaluation of Confiance Totale which investigates associations between campaign exposure and outcomes of interest. Following the broadcasts, the team conducted a cross-sectional household survey among 2,200 respondents ages 18 to 49. Combined and sex-stratified multivariable models predicting outcomes of interest controlled for sex, age, site, marital status, educational attainment, religion, and economic status. Upon hearing a campaign jingle, approximately 45% of participants had heard the campaign. Exposure to the campaign was associated with many ideational and behavioral outcomes including current use of a facility-dependent FP method (OR = 1.77, p < .001). In stratified models, several outcomes were significantly associated with exposure in the women-only models but not in the men-only models. Exposure to Confiance Totale was associated with nearly all ideational and behavioral outcomes of interest, particularly among women. This demonstrates that high dosage broadcasting may be effective in promoting confidence in the health system and improving perceptions of FP.

Despite decades of investment in family planning (FP) programming, contraceptive prevalence across the West African region remains low and fertility remains relatively high (Total Fertility Rate = 4.8) (Koffi et al., Citation2018; World Bank, Citation2022), with implications for the health and well-being of women and families. Studies associate use of FP with several positive outcomes including increased women’s empowerment, decreased maternal mortality, improved maternal and child health, and women’s improved economic status (Ahmed, Li, Liu, & Tsui, Citation2012; Canning & Schultz, Citation2012; Cleland, Conde-Agudelo, Peterson, Ross, & Tsui, Citation2012; Prata et al., Citation2017). In Togo, 26.6% of maternal mortality could be averted if unmet need for modern contraception was satisfied (Ahmed, Li, Liu, & Tsui, Citation2012).

Even with these benefits, in Togo, only 24% of married women between the ages of 15 and 49 reported currently using a modern method of FP and approximately 34% of women reported having unmet need for contraception (World Bank, Citation2022). Factors related to the non use of FP among those with unmet need include socio-cultural norms and practices, economic constraints, geographical inaccessibility, and low educational attainment among women (Ayanore, Pavlova, & Groot, Citation2016). One study of married Togolese men demonstrated that men are willing to learn about and participate in fertility and FP decision making but also have reservations related to FP use due to concerns about side effects and return to fertility (Koffi et al., Citation2018). Additionally, a qualitative study conducted in Ethiopia has demonstrated the influential nature of providers in affecting the quality of FP care and decisions surrounding method use and continuation (Yirgu, Wood, Karp, Tsui, & Moreau, Citation2020). This study among male and female adults reported that trust in providers both was generally high (particularly among health extension workers) and was of paramount importance for protecting client health (Yirgu, Wood, Karp, Tsui, & Moreau, Citation2020). However, some women reported distrust of providers regarding FP, and these women appeared to be less willing to ask questions and less able to access their preferred method (Yirgu, Wood, Karp, Tsui, & Moreau, Citation2020). Thus, in addition to structural barriers and social norms, trust in providers is likely to also be a major factor affecting propensity to use FP.

Social and Behavior Change Interventions and FP Use

Social and behavior change (SBC) can be defined as “activities or interventions that seek to understand and facilitate change in behaviors and the social norms and environmental determinants that drive those behaviors” (Rosen, Bellows, Bollinger, DeCormier Plosky, & Weinberger, Citation2019). SBC is often informed by communication theory and posits that the interventions will affect intermediate outcomes such as attitudes and social norms as well as behaviors. Such interventions can include radio, television, social media, interpersonal communication, or any combination of these approaches (Rosen, Bellows, Bollinger, DeCormier Plosky, & Weinberger, Citation2019). They can be effective in improving FP-related outcomes, but the results are often context-specific and dependent on the types of interventions used (Rosen, Bellows, Bollinger, DeCormier Plosky, & Weinberger, Citation2019).

West Africa Breakthrough ACTION and the Confiance Totale Theory of Change

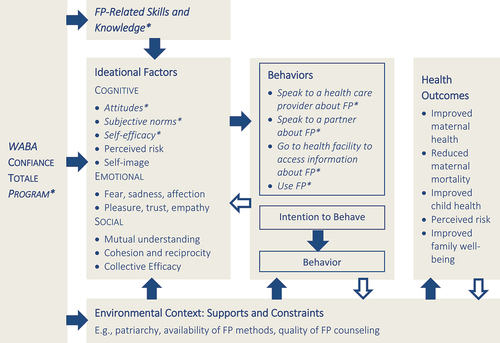

In order to promote client trust in FP methods and providers, the West Africa Breakthrough ACTION (WABA) project—a regional buy-in to the global Breakthrough ACTION project funded by USAID developed a quality assurance brand entitled “Confiance Totale.” The brand is based on Kincaid et al’s Ideational Model of SBC interventions, which posits that tailored communication can result in improvements in skills and knowledge as well as ideational constructs such as attitudes, perceived norms, self-efficacy, and social support (Kincaid, Citation2000; Kincaid, Delate, Storey, & Figueroa, Citation2012). The theory describes how communication will act through these ideational factors to increase the intention to use, and ultimately adopt a new behavior, such as a FP method in the case of the Confiance Totale campaign (Kincaid, Citation2000; Kincaid, Delate, Storey, & Figueroa, Citation2012). presents the Ideational Model of SBC applied to FP use and the Confiance Totale evaluation specifically.

Figure 1. Kincaid, Delate, Storey, and Figueroa (Citation2012) ideational model of health behavior change applied to FP & Confiance Totale.

WABA had planned to produce two radio spots promoting FP as part of its ongoing activities in the four countries of implementation. With the emergence of COVID-19 and the identification of the first cases in West Africa, the team anticipated that people would be spending more time at home (due to lock down orders) and staying away from health centers as places where COVID-19 transmission might happen. The program leveraged this as an opportunity to craft and share seven additional radio spots promoting couple communication about FP, and planning for FP method access, use, and uptake in this context of COVID-19 preventive guidance (e.g., mask wearing and physical distancing).

Radio Dissemination of Confiance Totale Program

In total, WABA created nine 45-second radio public service announcements (PSAs) that promoted the messages that FP methods are safe and effective, could be used successfully during the lockdowns, could be accessed from pharmacies, and that providers and hotlines were available to speak to clients about their concerns related to FP methods. Each of the PSAs contained a key message reminding audiences that FP methods and services were still available at health facilities staffed by caring and competent health care workers even during the COVID-19 pandemic. The project aired these PSAs in the four countries using the Saturation+ methodology (Murray et al., Citation2015) between May and September 2020. Development Media International (DMI) developed the Saturation+ approach, which is based on saturation, science, and stories (Murray et al., Citation2015). According to this approach, intensity is an essential component of any successful behavior change campaign; approach designers recommend broadcasting the messages in local languages 6–12 times per day for radio spots, 3 times per day for TV spots, and at least once per day for other formats (Murray et al., Citation2015).

Confiance Totale PSAs were re-broadcast in Togo from July 2021 to December 2021 on local radio stations. Each spot was broadcast on seven radio stations in French and in the two principal national languages 15 times per day, between the hours of 5:50 a.m. and 10:00 p.m.

The WABA research team then used the ideational model to develop and conduct a household survey with the following objectives: (1) to assess the level exposure to the Confiance Totale campaign among community members; (2) to understand whether the ideational model was an accurate representation of these data, as demonstrated by the relationship between exposure and ideational and behavioral reproductive health outcomes of interest (included in ); and (3) to understand associations between exposure to the campaign and the outcomes of interest differed between the men and women who were sampled.

Methods

The data in this paper come from a single cross-sectional household-based survey that was conducted in Lomé (Agoé Nyivè) and Blitta Ville (Blitta) in Togo in April 2022, among 2,200 respondents between the ages of 18 and 49. WABA carried out the survey in collaboration with the Togo-based action-research firm, CERA Group. The data collection team included a total of ten male interviewers, ten female interviewers, one male field supervisor, one female field supervisor, and a small oversight team who conducted daily debriefings and provided supervision throughout the data collection period.

Study Design

The team used a stratified random sample approach to collect data from 2,200 respondents who were evenly divided by site and by sex. In each of the 2 sites, the data collection team identified 44 enumeration areas (EAs) and used the random walk approach to sample every third household on the right side of the street. For each EA, the team sampled approximately 25 respondents.

Data Collection and Study Procedures

Data collection was conducted between April 18 and May 2, 2022. Upon arrival at the household, the research assistant read a brief recruitment/introductory script that described the reason for his or her visit to the head of household. The research assistant then used a modified Kish Grid approach to list all of the household members between the ages of 18 and 49 who were at home and who matched the sex of the research assistant. Once the team identified an appropriate person, it screened the potential subject for eligibility to participate in the study. Eligible potential respondents were those who were not currently exhibiting any signs of COVID-19, were between the ages of 18 and 49, and reported that they had had sexual intercourse in the six months prior to data collection. If the team deemed the individual eligible to participate, the research assistant read him or her the full consent script describing the study, the risks and benefits, and the participant’s rights. Upon providing oral consent to participate, the research assistant administered the survey using his or her mobile device and the KoboCollect application. Completion of the survey required about 30 minutes.

Ethical Approval

The institutional review board (IRB) at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (IRB 19143) and the Comité de Bioethique pour la Recherche en Santé (CBRS) in Togo (approval number 041) approved this study. All of the respondents in the study provided informed consent to participate and received sanitizing gel as a token of appreciation for participating in the study.

Data Management and Data Analysis

At the end of the data collection period, the study team downloaded data from the KoboCollect platform into.csv files and then uploaded those into Stata 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) for analysis.

For certain outcomes of interest, including current use of a facility-dependent method of FP, intention to use FP, having spoken to a health care provider about FP in the last month, and the intention to go to the health facility to obtain FP, we conducted the analysis among a subset of the respondents (referred to as the analytic sample; n = 1,610). The analytic sample excluded those who were pregnant (or their partner was pregnant), who reported not using FP because they (or their partner) wanted another child, and who reported not using FP because they were not having sex. These individuals were removed because they were not at risk of an unintended pregnancy. Analyses for all other outcomes of interest were run among the full sample (n = 2,200).

The team ran basic frequency distributions for all variables of interest and tested bivariate associations between exposure and outcomes of interest. It then used multivariable regression modeling to test these potential associations while controlling for other variables of interest including sex, age, site, marital status, educational attainment, religion, and wealth.

The team also ran gender-stratified models to test the associations with exposure among men and women separately.

Measures

presents the measures included in this evaluation including each of the individual items used to create scales and indices (where indicated).

Table 1. Summary of measures of interest included in the confiance totale evaluation analysis

Outcome Measures

The research team identified use of facility-dependent FP methods as the primary dependent variable of interest, given the program’s focus on increasing confidence in the health facility and in health providers. We measured use of facility-dependent FP methods using a combination of two variables. Surveyors asked respondents whether they were doing anything to delay or avoid pregnancy. Those who reported doing anything were then asked what they were using to avoid pregnancy. Respondents who reported using methods that were primarily available at the health facility were considered as facility-dependent FP users. These included female sterilization, vasectomy, intrauterine devices, oral contraceptive pills, medroxyprogesterone acetate (e.g., Depo-Provera by Pfizer), the implant, and/or emergency contraception. Those who reported using condoms, the rhythm method, the standard days method, lactational amenorrhea, withdrawal, or other were categorized as not using facility-dependent methods.

Reproductive autonomy, FP-related attitudes, FP-related social norms, and postpartum FP attitudes were also measured with multiple items and combined into scales. All of these scales were used as outcomes for this analysis and were developed using exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis as appropriate (results not shown). Reproductive autonomy can be defined as “having the power to decide about and control matters associated with contraceptive use, pregnancy, and childbearing” (Upadhyay, Dworkin, Weitz, & Foster, Citation2014, p. 20). In this analysis, the team focused on the communication sub-scale, which included items regarding couple communication about reproductive health decisions. Items comprising FP attitudes focused on the respondent’s perception of the acceptability, safety, and efficacy of FP methods. FP-related social norms included items that assessed the level of agreement surrounding descriptive and injunctive norms related to FP use. Finally, post-partum FP attitudes included three items that assessed the extent to which the participant agreed with women discussing and/or using FP methods within 6 weeks postpartum. FP knowledge was developed as an index, where participants received one point per correct response. Other single-item outcomes included intention to use FP, intention to visit a health facility for FP, having spoken with one’s partner about FP in the last month, the intention to speak to one’s partner about FP in the next month, self-efficacy to talk about FP at the health facility, and self-efficacy to talk to one’s partner about FP.

Exposure

To measure exposure, the data collection team played a Confiance Totale jingle and asked the respondent if he or she had ever heard radio messages like this in the past. Those who responded that they had were considered to be exposed to the campaign.

Control Variables

Socio-demographic control variables included age, respondent sex, district, marital status, educational attainment, religion and wealth index (an index variable).

Results

Descriptive Statistics/Characteristics of the Sample

presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the full and the analytic samples. The average age of the respondents included in the survey was 30.7 (SD = 8.04). Most of the respondents reported that they were married (n = 1,473, 67%) and almost one-half of them reported that they had attended some school or completed secondary education. The largest proportion of the sample was Catholic (n = 657, 29.9%) and the mean score on the wealth index was 3.87 (range: 0 to 6).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for key control variables of interest in Confiance Totale evaluation

presents the frequencies for exposure to the campaign and the outcomes of interest. Approximately 45% of the overall sample reported that they had heard radio messages when the Confiance Totale jingle was played. When assessed by sex in simple cross-tabulations with chi-squared tests, more men were exposed (56.3%) than women (34.4%) (χ2 = 103.3,p < .001) (results not shown). Nearly 27% reported that they themselves or their partner were currently using a facility-dependent method of FP at the time of the survey.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for exposure variable and outcomes of interest in confiance totale evaluation

Multivariable Regression Models

In multivariable models controlling for respondent age, sex, district, marital status, religion, educational attainment, and socio-economic status (), exposure to Confiance Totale was associated with many outcomes of interest including current use of a facility-dependent FP method (OR = 1.77, p < .001), intention to use FP (OR = 2.17, p < .001), intention to go to a health facility to obtain information about FP (OR = 1.77, p < .001), having spoken with one’s primary partner in the past month (OR = 1.45, p < .001), intention to talk to one’s partner about FP (OR = 1.47, p < .001), positive attitudes toward FP (β = 0.45, p < .001), the perception of supportive FP social norms (OR = 1.68, p < .001), positive postpartum FP attitudes (OR = 1.26, p = .02), increased knowledge of FP (β = 0.42, p < .001), increased self-efficacy to talk about FP at the health facility (OR = 1.86, p < .001), increased self-efficacy to speak with one’s partner about FP (OR = 1.39, p = .006), and increased reproductive autonomy (β = 0.73, p < .001). Having spoken to a health care provider in the last month was not statistically significantly associated with exposure to the Confiance Totale campaign.

Table 4. Multi-variable logistic regression models assessing associations between exposure to confiance totale and outcomes of interest, controlling for socio-demographic characteristics of interest (among the analytic sample)

Table 5. Multi-variable logistic and linear (shaded) regression models assessing associations between exposure to Confiance Totale and outcomes of interest, controlling for socio-demographic characteristics of interest (among the full sample)

In combined models (), men reported higher odds of intention to use FP (OR = 3.12, p < .001), FP communication in the last month (OR = 2.06, p < .001), intention to talk to one’s partner about FP (OR = 3.74, p < .001), and self-efficacy to talk to one’s partner about FP (OR = 2.85, p < .001), as compared to women. On average, men also reported more supportive FP attitudes (β = 0.68, p < .001), higher FP knowledge (β = 0.62, p < .001), and more reproductive autonomy (β = 1.26, p < .001) than women.

Men reported lower odds of the use of facility-dependent FP methods (OR = 0.69, p = .004) and having supportive postpartum FP attitudes (OR = 0.61, p < .001) compared to women. No statistically significant difference appeared between men and women in the odds of speaking to a health care provider in the last month (OR = 0.84, p = .288), the intention to go to a health facility for FP information and/or services (OR = 1.25, p = .071), self-efficacy to talk about FP at the health facility (OR = 1.21, p = .203), and FP-related norms (OR = 1.14, p = .274).

Sex Stratified Regression Models

In the sex stratified models (), we found slightly different patterns for men and for women. Associations between exposure to Confiance Totale and current use of facility-dependent FP methods was statistically significant overall as well as for men and women separately (Men: OR = 2.22, p = < 0.001; Women: OR = 1.40, p = .046). In addition, intention to use FP, intention to go to a health facility to access information about FP, intention to talk to one’s partner about FP, FP-related social norms, self-efficacy to talk about FP at the health facility, FP knowledge, and reproductive autonomy were associated with exposure to Confiance Totale among men and women in stratified models.

Table 6. Coefficients for dependent variables of interest from overall and stratified logistic and linear regression models- independent variable of interest is prompted exposure to the Confiance Totale campaign

Several outcomes were associated with exposure to Confiance Totale in women-only models but not in the models only for men. Of note, while having spoken with a health care provider overall was not associated with exposure in the combined model, this outcome did associate with exposure among women only (Men: OR = 0.77, p = .222; Women: OR = 1.86, p = .004). Other outcomes were associated with exposure in the combined models and in the women-only models. These outcomes included having communicated with one’s partner about FP in the last month (Men: OR = 1.27, p = .074; Women: OR = 1.65, p = .001), postpartum FP attitudes (Men: OR = 1.08, p = .569; Women: OR = 1.57, p = .003), and FP attitudes (Men: β = 0.33, p = .057; Women: β = 0.56, p = .004).

While self-efficacy to talk about FP with one’s partner was associated with exposure to Confiance Totale in the overall model, we did not find an association with exposure to the campaign in either of the stratified models (Men: OR = 1.39, p = .103; Women: OR = 1.31, p = .080).

Discussion

Results in Context

The results of this study demonstrate the overall successes of the Confiance Totale campaign in reaching the community and the associations between exposure to this campaign and FP-related outcomes of interest. In an evaluation of Confiance Totale in Côte d’Ivoire that used an interviewer-administered computer-assisted telephone survey approach, fewer than 20% of respondents reported that they had seen or heard the Confiance Totale campaign (Silva, Edan, & Dougherty, Citation2021). The lower rate in the Côte d’Ivoire study may be attributable to a concurrent presidential election, a more crowded media environment, and/or the lack of a prompted measure of exposure in the exposure survey. In this study in Togo, by contrast, these results demonstrated a 45% exposure to the campaign, higher than the survey in Côte d’Ivoire but lower than hypothesized given the frequency of the broadcasts and number of radio stations that were included. This level of exposure still falls short of the recommended high exposure (61% to 100%) needed to affect behavior change (Naugle & Hornik, Citation2014). In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluating a Saturation+ mass radio campaign in Burkina Faso, the authors report achieving 82% self-reported exposure among women in the intervention group (Sarrassat et al., Citation2018). Because the airing of the Confiance Totale campaign (July 2021–December 2021) occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, competing messages may have aired regarding COVID-19 prevention, testing, and vaccination that were more salient for the respondents. In addition, the survey occurred 4 months after the Confiance Totale spots had been aired. Therefore, the lower reported exposure could also be attributable, in part, to recall limitations among respondents. Nonetheless, the consistent associations between exposure and FP outcomes may suggest that high quality and strategic communication affect outcomes, even at lower levels of population exposure.

Associations with Outcomes

In the combined multivariable regression models, those who reported being exposed to Confiance Totale had increased odds of several ideational factors that are proximate to FP use including intention to use FP, intention to go to a health facility, communication about FP with one’s partner in the last month, intention to talk to one’s partner about FP, FP-related norms, postpartum FP attitudes, self-efficacy to talk about FP at the health facility, and self-efficacy to talk to one’s partner about FP. In these adjusted models, those who were exposed had higher scores on FP attitudes and perceived supportive FP social norms, higher levels of knowledge related to FP, and higher levels of reproductive autonomy. Those who were exposed to Confiance Totale had higher odds of currently using a facility-dependent method of FP as well.

These results are consistent with the Confiance Totale evaluation in Côte d’Ivoire, which found that exposure to the campaign was associated with belief in the safety of FP methods (men and women), spousal communication about FP (women only), high self-efficacy to communicate with one’s partner about FP (women only), intention to communicate with one’s partner about FP (women only), intent to go to a health facility to seek FP information (men and women), communication about FP with a health provider in the past month (men and women), and current use of FP (men and women) (Silva, Edan, & Dougherty, Citation2021).

The results demonstrate the promise of high intensity and high frequency approaches to behavior change communication campaign (Sarrassat et al., Citation2018). In addition, other studies have demonstrated the cost-effectiveness of high intensity mass media communication and the potential for economies of scale (Kasteng et al., Citation2018; Rosen, Bellows, Bollinger, DeCormier Plosky, & Weinberger, Citation2019). Thus, the results of this work contribute to the growing body of evidence that suggests that mass media communication remains a cost-effective strategy for SBC and can contribute toward reductions in disability-adjusted life years at a reasonable cost.

Gender Analysis

This study also provided valuable insights into the gender landscape and how exposure to the campaign might affect men and women differently. The results demonstrate that the men sampled have higher scores on many of the proximate determinants of FP use. It is not possible to know whether this reflects men’s true experience or desirability bias from these data. In a recent study in Togo, men reported being supportive of FP use, particularly due to socio-economic concerns (Koffi et al., Citation2018). These authors referenced ongoing initiatives in Togo to increase the participation of men in reproductive decisions including the use of male motivators (positive deviant model), social marketing, and mHealth interventions (Koffi et al., Citation2018). These programs may have been effective in improving either men’s FP attitudes and behaviors or, at least, their awareness of socially desirable responses. Additionally, even in dyadic couples’ studies, researchers have long noted the discordance between reports of contraceptive outcomes including use and communication between husbands and wives (Diro & Afework, Citation2013; Dixit et al., Citation2021; Govil & Khosla, Citation2020). Men and women, despite responses to survey questions, possibly may have poor communication about FP use that causes them to misinterpret the current use status of their partner.

Beyond contraceptive use, men reported higher scores on many ideational constructs related to FP. They reported higher self-efficacy, knowledge, communication with their partner, and reproductive autonomy than women in the sample. That these differences could arise due to their relatively higher position in society and their decision-making power. In fact, the National FP Plan of Action for Togo reports women consistently have had lower awareness of FP and are less able to access communication channels compared to men (Ministere de la Santé et de la Protection Sociale, Citation2017). This report states that in 2014, 17.9% of married women had heard FP messages on the radio while 47.2% of married men reported the same (Ministere de la Santé et de la Protection Sociale, Citation2017). The inequitable access to radio, television, and newspapers may contribute to women lacking the information and autonomy needed to make independent FP decisions (Ministere de la Santé et de la Protection Sociale, Citation2017).

Several outcomes were positively associated with exposure among women only. Women who had been exposed to the campaign had higher odds of speaking to a health care provider in the last month, higher odds of communicating with their partner in the past month, and more accepting FP attitudes generally and postpartum FP attitudes. However, while men had significantly higher levels of exposure to Confiance Totale than women and higher overall scores on FP communication with partner and FP attitudes, the relationship between exposure and these outcomes was not significant among men. Of note, the association between campaign exposure and communication with partner about FP (as well as the self-efficacy to do so) was not significant among men in the stratified model. This limits the plausibility of a pathway effect from exposure among the men to increased male FP engagement with women to increases in FP use. In contrast, the effects of the campaign across multiple domains among women was consistent from the results of the evaluation of Confiance Totale in Côte d’Ivoire (Silva, Edan, & Dougherty, Citation2021). Taken together, this may suggest that while the radio campaign was more likely to reach men, the Confiance Totale program messages may have been better tailored to women.

Limitations

This study has several important limitations to consider. First and foremost, the data collection period occurred during Ramadan, a period during which consideration and conversation about sex may be considered inappropriate. Perhaps due to this, we received a greater than expected number of refusals to participate in the study. Among individuals who were approached and eligible for an interview, the response rate was 87.3%. Of the 319 refusals to participate, 34.4% (n = 110) reported that they did not want to discuss FP specifically. This may have resulted in a bias in our sample such that a lower proportion of participants were Muslim, and those who agreed to participate might already have had more accepting views of FP. In addition, the evaluation design utilized a single cross-sectional survey (and did not include a baseline assessment), which does not allow for understanding of temporality, nor considerations of causality and, therefore, the results cannot claim causal attribution. Rather, respondents who used FP or had more supportive attitudes or norms may have been more likely to remember Confiance Totale campaign messages. Given the other concurrent FP related activities in the study areas, the differences we observed between participants who recalled hearing the Confiance Totale jingle and those who did not may be attributable to a constellation of FP-related communication initiatives. In terms of the sampling approach, those eligible for participation in the survey included those who were at home at the time that the interviewer arrived. While this was done to increase the efficiency of the data collection, it may have resulted in a bias in the sample. Furthermore, while the study was adequately powered to detect differences among the entire sample, the sample sizes for the sex specific regression models may have been inadequate to detect the effect of exposure among men and among women. Therefore, we advise caution in interpreting a null result for the men-only and women-only models with odds ratios in the expected direction but a non-significant p value. In addition, the measures of exposure did not capture which of the Confiance Totale spots each respondent heard, nor the frequency with which each spot was heard. This information would have been challenging to collect due to recall bias but would have been helpful in understanding the most and least effective spots and their relationships with outcomes of interest. Finally, given the campaign’s focus on promoting trust in the health facility and in providers, the team selected facility-dependent methods of FP as the primary behavioral outcome. This measure excluded condoms, often considered a modern method, as they are often easily accessible through pharmacies, grocery stores, NGOs, and other distribution points. This resulted in a rate of facility-dependent FP use (26.6%) that is similar to the current contraceptive rate for women in Togo generally (24.1%) (World Bank, Citation2022). As such, the primary outcome for this study is different from the most often used measure of modern contraceptive prevalence, perhaps contributing to limitations in external validity.

Programmatic Implications

The results of this evaluation may demonstrate effectiveness of mass media communication using a Saturation+ dissemination approach. These results demonstrate an association between Confiance Totale exposure and nearly all FP-related outcomes of interest. Interestingly, the effects of the campaign appeared to be more pronounced among women, who typically had lower overall scores on the outcomes of interest compared to men. This result provides evidence of the value of additional FP programming for increasing women’s reproductive autonomy and continuing to work with men to support women’s reproductive decisions and joint FP decision making.

While the level of exposure was lower than expected for a Saturation+ campaign, the consistent association between exposure to the campaign and positive ideational and behavioral variables may demonstrate the enduring effects of the campaign- even when no longer being actively broadcast. The results of this evaluation suggest mass media campaigns can be an effective way to reach individuals about FP within the context of disruptive or emergency contexts, such as those created by the COVID-19 pandemic. While this evaluation did not include a cost-effectiveness analysis, other studies have demonstrated the cost-effectiveness of high-intensity mass media communication and the potential for economies of scale (Kasteng et al., Citation2018; Rosen, Bellows, Bollinger, DeCormier Plosky, & Weinberger, Citation2019). The results of this work contribute to the growing body of evidence that suggests that mass media communication remains a cost-effective strategy for SBC and can contribute to reductions in disability-adjusted life years at a reasonable cost.

Ethics Approval Statement

This study was approved by the IRB at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (IRB 19143) and the Comité de Bioethique pour la Recherche en Santé in Togo (approval number 04). All members of the study team received training on ethical conduct for human subjects’ research.

Patient Consent Statement

All of the respondents in the study provided informed consent to participate and received sanitizing gel as a token of appreciation for participating in the study.

Permission to Reproduce Material from Other Sources

We have reached out to Sage to seek permission to use the adapted figure from Larry Kincaid’s publications. Upon acceptance, we can finalize the process.

Data Availability Statement

The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly, so due to the sensitive nature of the research, supporting data is not available.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmed, S., Li, Q., Liu, L., & Tsui, A. O. (2012). Maternal deaths averted by contraceptive use: An analysis of 172 countries. The Lancet, 380(9837), 111–125. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60478-4

- Ayanore, M. A., Pavlova, M., & Groot, W. (2016). Unmet reproductive health needs among women in some West African countries: A systematic review of outcome measures and determinants. Reproductive Health, 13(1), 1–10. doi:10.1186/s12978-015-0104-x

- Canning, D., & Schultz, T. P. (2012). The economic consequences of reproductive health and family planning. The Lancet, 380(9837), 165–171. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60827-7

- Cleland, J., Conde-Agudelo, A., Peterson, H., Ross, J., & Tsui, A. (2012). Contraception and health. The Lancet, 380(9837), 149–156. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60609-6

- Diro, C. W., & Afework, M. F. (2013). Agreement and concordance between married couples regarding family planning utilization and fertility intention in Dukem, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health, 13(1). doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-903

- Dixit, A., Johns, N. E., Ghule, M., Battala, M., Begum, S. … Raj, A. (2021). Male–female concordance in reported involvement of women in contraceptive decision-making and its association with modern contraceptive use among couples in rural Maharashtra, India. Reproductive Health, 18(1). doi:10.1186/s12978-021-01187-8

- Govil, D., & Khosla, N. (2020). Concordance in spousal reports of current contraceptive use in India. Journal of Biosocial Science, 53(4), 606–622. doi:10.1017/S0021932020000437

- Kasteng, F., Murray, J., Cousens, S., Sarrassat, S., Steel, J. … Borghi, J. (2018). Cost-effectiveness and economies of scale of a mass radio campaign to promote household life-saving practices in Burkina Faso. BMJ Global Health, 3(4), e000809. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000809

- Kincaid, D. L. (2000). Mass media, ideation, and behavior: A longitudinal analysis of contraceptive change in the Philippines. Communication Research, 27(6), 723–763. doi:10.1177/009365000027006003

- Kincaid, D. L., Delate, R., Storey, D., & Figueroa, M. E. (2012). Closing the gap in practice and theory: Evaluation of the scrutinize HIV campaign in South Africa. In R. E. Rice & C. K. Atkins (Eds.), Public communication campaigns (pp. 305–319). Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC and Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Koffi, T. B., Weidert, K., Bitasse, E. O., Adjoko, M., Mensah, E. … Prata, N. (2018). Engaging men in family planning: Perspectives from married men in Lomé, Togo. Global Health Science and Practice, 6(2), 317–329. www.ghspjournal.org. 10.9745/GHSP-D-17-00471

- Ministere de la Santé et de la Protection Sociale. (2017). Plan d’action national budgétisé de planification familiale 2017–2022 du Togo. https://fp2030.org/sites/default/files/PANB_PF_2017-2022_Togo_HP.pdf

- Murray, J., Remes, P., Ilboudo, R., Belem, M., Salouka, S. … Head, R. (2015). The Saturation+ approach to behavior change: Case study of a child survival radio campaign in Burkina Faso. Global Health Science and Practice, 3(4), 544. doi:10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00049

- Naugle, D. A., & Hornik, R. C. (2014). Systematic review of the effectiveness of mass media interventions for child survival in low-and middle-income countries. Journal of Health Communication, 19(sup1), 190–215. doi:10.1080/10810730.2014.918217

- Prata, N., Fraser, A., Huchko, M. J., Gipson, J. D., Withers, M. … Upadhyay, U. D. (2017). Women’s empowerment and family planning: A review of the literature. Journal of Biosocial Science, 49(6), 713–743. doi:10.1017/S0021932016000663

- Rosen, J. E., Bellows, N., Bollinger, L., DeCormier Plosky, W., & Weinberger, M. (2019). The business case for investing in social and behavior change for family planning. The Population Council. https://breakthroughactionandresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/20191211_BR_FP_SBC_Gdlns_Final.pdf

- Sarrassat, S., Meda, N., Badolo, H., Ouedraogo, M., Some, H. … Head, R. (2018). Effect of a mass radio campaign on family behaviours and child survival in Burkina Faso: A repeated cross-sectional, cluster-randomised trial. The Lancet Global Health, 6(3), e330–e341. doi:10.1016/s2214-109x(18)30004-4

- Silva, M., Edan, K., & Dougherty, L. (2021). Monitoring the quality assurance branding campaign confiance totale in Côte d’Ivoire [technical report]. The Population Council. https://breakthroughactionandresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/BR_Confiance_Totale_Rprt.pdf

- Upadhyay, U., Dworkin, S., Weitz, T., & Foster, D. (2014). Development and validation of a reproductive autonomy scale. Studies in Family Planning, 45(1), 19–41. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00374.x

- World Bank. (2022, February 24). Togo. The World Bank Data Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/country/TG

- Yirgu, R., Wood, S. N., Karp, C., Tsui, A., & Moreau, C. (2020). “You better use the safer one… leave this one”: The role of health providers in women’s pursuit of their preferred family planning methods. BMC Women’s Health, 20(1). doi:10.1186/s12905-020-01034-1