Abstract

Understanding the factors associated with acceptance of climate action is central in designing effective climate change communication strategies. An exploratory factor analysis of 12 science-consistent beliefs about the existence, causes, and consequences of climate change reveals three underlying factors: climate change [a] is real and human caused, [b] has increased the frequency of extreme weather events, and [c] negatively affects public health. In the presence of demographic, ideological, and party controls, this health factor significantly predicts a 3–6 percentage point increase in respondents’ [a] willingness to advocate for climate change; [b] reported personal pro-climate behaviors; and [c] support for government policies addressing climate change. These results are robust when controlling for respondents’ underlying belief in the existence and causes of climate change, respondent worry, self-efficacy, and respondent belief that extreme weather events and heat waves are increasing. These findings suggest ways to bolster public support for climate policies that may otherwise be at risk.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has concluded that “[c]limate change will significantly increase ill health and premature deaths from the near to long term” (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Citation2023), and systematic reviews have identified an association between climate change and many negative individual and population-level human health outcomes (Rocque et al., Citation2021). In like fashion, The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that “[b]etween 2030 and 2050, climate change is expected to cause approximately 250,000 additional deaths per year, from undernutrition, malaria, diarrhoea and heat stress alone” (World Health Organization, Citation2023). At the same time, climate change is “changing the seriousness or frequency of health problems that people already face,” and “creating new or unanticipated health problems in people or places where they have not been before” among these “respiratory and heart diseases, pest-related diseases like Lyme disease and West Nile Virus, water- and food-related illnesses, and injuries and deaths” (U.S. EPA, Citation2024). Moreover, underserved communities are more likely to experience such health effects with pronounced racial disparities (Berberian et al., Citation2022).

The greatest threat to global public health is the continued failure of world leaders to keep the global temperature rise below 1.5° C and to restore nature,” declared the editors of health journals throughout the globe including The Lancet, The New England Journal of Medicine and the British Medical Journal, in an unprecedented common editorial in 2021: “Urgent, society-wide changes must be made and will lead to a fairer and healthier world. (Atwoli et al., Citation2021)

Understanding the factors that might affect public support for responsive policies and behaviors is important because the need to address climate change is urgent. In the search for foci that may affect behaviors and policy support, health frames and topics are seen as promising by some (Myers et al., Citation2012) but less so by others (Li & Yi-Fan Su, Citation2018).

Evidence about the extent to which holding health-related climate beliefs predicts support for climate policies is mixed and necessarily context-dependent. A five-nation study concluded that health and environmental frames were among those able to bolster public support for climate policies (Dasandi et al., Citation2022) and some studies have associated perceptions about climate change with both behavior and support for policy proposals (Bolderdijk et al., Citation2013). However, a meta-analysis of data from 106 studies conducted in 23 different countries that examined the relationship of 13 motivational factors to various climate change adaptation behaviors found that belief was relatively weakly related to adaptation (A. van Valkengoed & Steg, Citation2019). In that meta-analysis, studies assessing policy support reported positive relationships while those focused on preparedness reported non-significant ones. Such associations with behavior also may be stronger when the message is tailored to respondents and consistent with their values (Bolderdijk et al., Citation2013). However, the relationship between climate change beliefs and willingness to act in climate-friendly ways may be relatively small (Hornsey et al., Citation2016)

A belief can be consistent or inconsistent with convergent science. We define science-consistent beliefs as those that are consistent with the conclusions reached by expert organizations that serve as custodians of the best available knowledge about the scientific matter at issue (Jamieson et al., Citation2017). In the case of climate change, these would include the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the National Climate Assessment (NCA), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the National Academy of Sciences (NAS).

Here we ask whether in a polarized political time, science-consistent beliefs about the harmful effects of climate change on public health will predict important forms of climate friendly policy support, projected advocacy, and individual behavior over other predictors of behavior including individuals’ worry, self-efficacy, and trust in federal climate-relevant entities and, if so, whether that effect will survive controls for ideology and party.

Variables

Independent Variables

Science-Consistent Climate Health Beliefs

Van Valkengoed et al. (Citation2021) have shown that perceptions of the reality, causes, and consequences of climate change are empirically distinguishable. Moreover, they find that believing climate change is real and human caused may not elicit responsive action unless respondents also perceive that climate change is having negative effects (Van Valkengoed et al., Citation2021). To corroborate this finding, we conducted a exploratory factor analysis on 12 items assessing respondents’ science-consistent beliefs about the existence, causes, and consequences of climate change. References documenting the science consistency of these items can be found in Appendix A. The distribution of responses can be found in .

Table 1. Science-Consistent Climate Health Beliefs

We recode each item such that 1 is the most science-consistent response and 0 science-inconsistent. Those responding “Or are you not sure?” are coded at the middle of the distribution. We uncovered three underlying factors (see ) corresponding with respondents’ perceptions of [a] the health risks posed by climate change (α=.87); [b] that extreme weather and heat waves are increasingly frequent (α=.79); and [c] climate change is occurring and human caused (α=.83). An analysis of the variance confirms that this three-factor model better describes respondents’ science-consistent climate beliefs than a one-factor model.Footnote1

Table 2. Factor analysis

Our primary focus in this study is on the eight science-consistent climate health items concerning the health risks posed by climate change—illness and disease, water-borne diseases, insect- and tick-borne disease, mental health, death, premature delivery, negative effects on fruits and vegetables, and the disproportionate health impact on low-income individuals. To avoid biasing the items, each of the eight offered respondents an encompassing list of options (e.g., increasing risk, decreasing risk, having no effect on risk; less likely, more likely, just as likely; negatively affecting, positively affecting, or having no effect, etc.). Importantly, existing work shows that Americans find illnesses from contaminated food and water, and disease-carrying organisms particularly worrisome (Kotcher et al., Citation2018).

Trust in Public Institutions

Because individuals’ political ideology is associated with their trust in federal scientific research (Myers et al., Citation2017) and trust in scientists and environmental groups correlates with climate-friendly behaviors (Cologna & Siegrist, Citation2020), we assessed trust in two climate-related federal agencies by asking “how confident, if at all, are you that that the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)” [or] “the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is providing the public with trustworthy information about matters concerning the effects of climate change on public health” (see ). We average these two items (α=.76) to measure trust in relevant institutions. These questions parallel those asked about the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in prior work predicting acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination (Jamieson et al., Citation2021; Romer et al., Citation2022).

Table 3. Confidence in public institutions

Worry About Climate Change

Survey researchers in the U.S. have found that worry about global warming is strongly associated with support for responsive policies (Smith & Leiserowitz, Citation2014; Goldberg et al., Citation2021). Likewise, the European Social Survey, involving 44,387 respondents from 23 countries found an association between heightened worry about climate change and support for and taking climate action (Bouman et al., Citation2020). These findings are consistent with the theory that negative emotions increase the likelihood of action designed to reduce the cause (Brosch & Steg, Citation2021). To operationalize worry, we asked all respondents “to what extent climate change already poses or will pose a serious threat to you or your way of life in your lifetime.” Forty-two percent (42%) of respondents reported “a lot” or “a great deal.”

Self-Efficacy

Because self-efficacy is an important determinant of intentions and behavior (Bandura, Citation1977; Sheeran et al., Citation2016), all panelists were asked which of the following comes closest to your view: “There is nothing an individual like me can do to address climate change;” “there are things that an individual like me can do to address climate change that will make at least some difference;” or “climate change is not happening.” Fifty-eight percent (58%) of respondents reported believing that there were things “that an individual like me can do to address climate change that will make at least some difference.” We use this item to operationalize the agency an individual felt about personally affecting climate change.

Dependent Variables

Willingness to Advocate for Climate Change

Advocacy plays a key role in eliciting support for responsive policy (Mendoza-Vasconez et al., Citation2022). Because those who believe that their actions matter are more likely to engage in various ways (Ng & Feldman, Citation2012), all panelists were asked: “How likely, if at all, would you be to write letters, emails, or phone government officials about climate change” [or] “sign a petition about climate change, either online or in person if a person you like and respect asked you to?” (see ). We average the responses to these two items (α=.81) to form an advocacy scale ranging from 0 to 1.

Table 4. Willingness to advocate for climate change

Pro-Environmental Policy Support

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) has been called by some “the most significant federal climate and clean energy legislation in U.S. history” (U.S. EPA, 2022). That legislation directed billions of dollars in subsidies to a wide range of pro-climate programs, including battery manufacturing, residential solar installation, electric car purchases, and clean energy retrofitting. Climate modeling teams estimate that the IRA’s provisions may reduce U.S. greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 33% to 40% by 2030 compared to 2005 levels (Bistline et al., Citation2023). “The legislation will spend roughly $374 billion on decarbonization and climate resilience over the next 10 years, getting us two-thirds of the way to America’s Paris Agreement goals” (Meyer Citation2022). Magnifying the urgency of building protective levels of public support for pro climate policies in the Inflation Reduction Act are the facts that it passed and became law without any Republican support in either the U.S. House or Senate and hence could be repealed in a Republican-controlled Congress and, in any event, would be vulnerable to hostile exercises of executive authority should former President Trump win another term (Frazin, Citation2024).

Five Items from the IRA

Without explicitly naming the IRA, we focused on five policies embodied in it, namely, support for or opposition to [1] “increased investment in energy-efficient forms of public transportation;” [2] “a tax credit for families who install rooftop solar or battery storage in their homes;” [3] “a tax credit for drivers who buy electric cars;” [4] “providing rural communities with access to forgivable loans to improve their energy efficiency;” and [5] “grants to communities to protect them from the impacts of climate change, including drought, heat, and extreme weather.” Support for these five items is averaged (α=.89) into a scale of support for pro-environmental policies ranging from 0 to 1.

Carbon Emission Tax

Because a carbon emissions tax enjoys wide support among economists but has proven politically unviable, increasing public support for it would be a desirable outcome. In 2019, 47 economists signed an open letter confirming that a carbon emissions tax would offer “the most cost-effective lever to reduce carbon emissions at the scale and speed that is necessary” (Climate Leadership Council, Citation2024). Since then, over 3,500 U.S. economists have signed it (ibid.). Accordingly, we also included an item assessing support for or opposition to “taxing corporations based on the amount of carbon emissions they produce to reduce the effects of climate change.” summarizes respondents’ support for these six policies (5 items from the IRA and the carbon emission tax item).

Table 5. Support for pro-environmental policies

Pro-Environmental Behaviors

All panelists were asked which, if any, of items on a list of changes they had made in recent years. They were then presented with a randomized list of ten pro-environmental activities, such as “installed solar panels,” “reduced your use of plastics,” “increased your consumption of plant-based foods,” etc. (see ).

Table 6. Pro-environmental behaviors

Rationale for Controls

College educated, liberal, and Democratic respondents were more knowledgeable, worried, and trusting in federal climate-related agencies, whereas, conservative, Republican, and Black respondents were less so (see Appendix C). As a result of these group differences, all models control for respondents’ age, educational attainment, gender, ideology (i.e., Conservative, Moderate, Liberal), partisan identification (i.e., Democrat, Independent, Republican), and racial/ethnic identity. The distribution of these demographic categorizations can be seen in .

Table 7. Sample demographics

Survey Methods

Data Collection

The data for this study were collected from the Annenberg Science and Public Health (ASAPH) survey, a nationally representative probability panel survey drawn randomly from the SSRS Opinion Panel of U.S adults, 18 and older. Panelists were recruited based on nationally representative address-based-sample design (including Hawaii and Alaska). Hard-to-reach demographic groups were also recruited via the SSRS Omnibus survey platform, a nationally representative bilingual telephone survey. Both the phone and online surveys were available in Spanish; about 2% of respondents chose this option. Panel members had not participated in any other studies conducted by SSRS prior to their selection and the panel is annually scrubbed of panelists who enroll in other survey panels. Panelists were invited by e-mail or telephone to participate and were paid $15 for participation in each wave. The median length of the surveys was 20 minutes and are scheduled roughly quarterly. The survey was deemed exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania.

Of the 3,476 U.S. adult panelists invited to participate in wave 1 of the survey, 1,941 completed the first survey in April 2021 (56% completion rate). The panel underwent a partial replenishment in Winter 2022 to account for attrition and to improve the representativeness of the panel. Of the replenished 1,975 current panelists, 1,538Footnote2 (78%) completed the Climate Health and Communication survey between November 14–20, 2023. None of the knowledge or climate worry questions asked of the respondents appeared on any previous wave of the survey. The last time a climate-related knowledge question was asked on wave 8 of the survey (August 2022). The survey was weighted to be representative of the U.S. population and all item summaries and models herein adjust using these post-stratification weights, with an overall design effect of 1.73. More details on sampling and weighting, including the population benchmarks to which we adjust, can be found in Appendix D. The full survey instrument, including question wording and ordering, can be found in Appendix E.

Statistical Analyses

All models are estimated using linear regressions that account for post-stratification weights using the lfe package in R version 4.3.1. Scripts to replicate the analyses are available at https://osf.io/g4wvh/.

Results

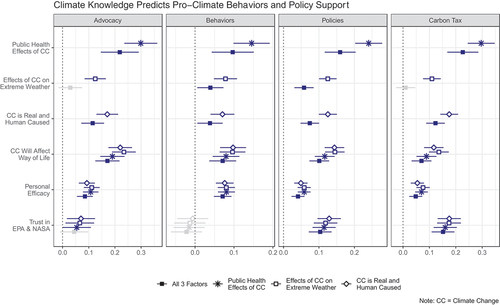

provides the model estimates for our three dependent variables for four different model specifications – the three-factor model and each factor modeled alone.Footnote3 The first specification (All 3 Factors) shows a strong association between science-consistent climate attitudes as measured by all items in our battery. Here we see that after controlling for demographics, confidence in the EPA and NASA, personal efficacy, and worry about the effects of climate change, science-consistent beliefs about the existence, causes, and health consequences of climate change and perception that extreme weather and heat waves are increasing in frequency have a significant (p < .001) association with pro-climate behaviors and policy support.

Each of the three factors (perception that climate change is occurring and human cause, that extreme weather and heat waves are occurring more frequently, and that climate change has and will have negative effects on health) independently predicts respondents’ willingness to advocate for climate action and respondents’ self-reported pro-climate behaviors. Two of the three factors – negative effects on health and (Factor 1) and climate change is real and human caused (Factor 3) – independently predict support for pro-climate policies. However, when modeled individually, all three dimensions are significant predictors across all four of our outcomes (advocacy, individual pro-climate behavior, support for IRA provisions, and support for carbon emissions tax).

Among these three factors, a science-consistent understanding of the negative health effects climate change has the strongest and most consistent association with our four pro-climate outcomes. A one standard deviation (0.27) increase in science-consistent beliefs concerning health corresponds with a 6.1% point (pp) increase in respondents willingness to advocate, a 4.5pp and 6.3pp increase in support for pro-climate policies in the IRA and the carbon emission tax,Footnote4 and a 2.7pp increase in reported pro-climate behaviors.

Robustness Checks

One concern may be that climate-skeptical respondents are purposefully responding in a science-inconsistent manner to the items in our battery and not truly measuring science-consistent beliefs. However, our factor analysis uncovered one dimension consisting of two-items: [1] Increases in the Earth’s temperature over the last century are due more to the effects of pollution from human activities; and [2] Human activities are significantly affecting the rate of climate change. While both are science-consistent conclusions based on the best available scientific evidence, they could also be measuring an underlying belief in climate change. To address this concern, we control for this factor (belief that climate change is occurring and human caused). After doing so, belief in the negative health effects of climate change remains significantly (p < .001) associated with a willingness to advocate if asked, self-reported pro-climate behaviors, and support for policies aimed at addressing climate change. In other words, even among those with similar beliefs about the existence of climate change, greater belief in its negative health effects is associated with more pro-climate behaviors and policy support.

To further address the concern that these items may not be measuring science-consistent beliefs, we re-estimated the models from dropping any respondent who reported that “climate change is not happening” in any of the items for which this was a possible response. Approximately seven percent (7.2%) of respondents provided this response at least once. After dropping these respondents, we found similar results (see Appendix C).

Importantly, when we asked respondents “[w]hich, if any, of the following changes have you made in recent years?,” we did not ask whether respondents’ had climate motivations for taking those actions. Instead, after asking all possible behaviors, we asked whether the “main reason that you engaged in the action(s) you just reported” were [a] “to minimize impact on climate change;” [b] “to save money;” [c] “both reduce impact on climate change and save money;” or [d] “some other reason.” Among respondents who had taken at least one pro-climate action, 65.3% ([a] + [c]) reported a climate-related motivation.

If, as we hypothesize, science-consistent beliefs about the existence, causes, and consequences of climate change are driving individuals toward more pro-climate attitudes and behavior, then we would expect an association between these science-consistent beliefs only among those who report a climate motivation for those actions. In other words, science-consistent beliefs about climate change shouldn’t drive people “to save money.”

When we re-estimated our model of reported pro-climate behaviors from on those who reported [a] climate or both climate and financial reasons and [b] no climate motivations, we found that science-consistent climate health beliefs were positively associated with the number of pro-climate actions taken only among respondents who reported climate-related motivations for taking those actions.Footnote5 Among those reporting only financial or other motivations only the perception that extreme weather and heat waves are increasing in frequency predicted pro-climate behaviors. Importantly, neither item underlying this weather factor explicitly mentions climate change.

Limitations

First, since our data are cross-sectional we cannot draw causal conclusions. Second, as our data are drawn from an on-going panel, attrition and sensitization could affect our conclusions. However, the ASAPH panel uses both replenishment and post-stratification weights to maintain a representative panel of U.S. adults and has maintained consistently high participation rates between 75 and 80%. Third, our list of items drawn from the IRA did not explicitly mention that piece of legislation as their source or indicate that the legislation passed without Republican support and was signed into law by a Democrat. This political information would likely dampen the effects observed in . However, the association between science-consistent beliefs and support for pro-climate policies remains in the presence of controls for political ideology and party identification.

Discussion

In a political environment characterized by a contest over the existence, nature, extent, effects, and responses to climate change, understanding the factors associated with the acceptance of climate action is important. Drawing on responses from a November 2023 national probability sample of 1,538 of U.S. adults, this study finds that science-consistent beliefs concerning the public health implications of climate change predict respondents’ [a] willingness to engage in climate change advocacy; [b] reported pro-climate behaviors; [c] support for five climate-related provisions in the IRA; and [d] support for a carbon emissions tax.

An exploratory factor analysis of the responses to our 12 climate items identified three factors underlying science-consistent climate beliefs: [a] climate change is real and human caused; [b] extreme weather is increasing in frequency; and [c] climate change negatively affects health.

The fact that the association between the latter and our pro-climate outcomes remains after controlling for the other two dimensions suggests that these science-consistent beliefs are significant after controlling for above individuals’ belief that climate change is happening.

Recall that across all three measures college educated, liberal, or Democratic respondents were more science-consistent, worried, and trusting in federal climate-related agencies, whereas conservatives, Republicans, or Black respondents were less so. These differences suggest the desirability of climate messaging that reinforces existing science-consistent health beliefs and behaviors with the former while deploying messaging that bolsters trust in federal agencies, increases climate worry, and uses trusted sources to increase science-consistent climate health beliefs among the latter.

Given the polarization of the politics of climate change and the existence of a closely divided electorate, climate-friendly policies in The Inflation Reduction Act may face roll-back efforts. Increasing public support for them could increase the political costs of attempting such a roll-back. Here we show that, even in the presence of controls for ideology and party, individuals’ belief in the negative health effects of climate change – that, for example, it will increase the spread of infectious diseases, reduce the quality of agricultural production, exacerbate health disparities for vulnerable populations, and has increased the number of deaths– is associated, with pro-climate action and policy support.

Acknowledgments

A Robert Wood Johnson Foundation grant provided support for identification of our science-consistent climate health belief items. The authors wish to thank Anthony Leiserowitz, Edward Maibach, Marshall Shepherd, and Eryn Campbell for helpful critique of an early draft of a survey instrument, Ken Winneg for managing the survey process, and Rachel Askew, James Noack, and Jennifer Su of SSRS for their assistance implementing the survey.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

Data, R code, and documentation necessary to replicate the analyses will be deposited in OSF upon publication: https://osf.io/g4wvh/

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See Appendix B for more details on this exploratory factor analysis and model diagnostics.

2 Of the 1,538 respondents, 1,479 (96.2%) provided complete demographic profiles and answers to all questions used in the models presented in . Topline results report the distributions for all valid responses, whereas the models report the subset of respondents who completed all items. No missing data is imputed.

3 These figures omit the coefficients for demographic controls, which can be found in Appendix C.

4 Full results can be found in Appendix C.

5 The full model results for each of these robustness checks can be found in Appendix C.

References

- Atwoli, L., Baqui, A. H., Benfield, T., Bosurgi, R., Godlee, F., Hancocks, S., & Vázquez, D. (2021). Call for emergency action to limit global temperature increases, restore biodiversity, and protect health. The Lancet Regional Health–Western Pacific, 14, 14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100274

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Berberian, A. G., Gonzalez, D. J. X., & Cushing, L. J. (2022, September). Racial disparities in climate change-related health effects in the United States. Current Environmental Health Reports, 9(3), 451–464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-022-00360-w. Epub 2022 May 28. PMID: 35633370; PMCID: PMC9363288.

- Bistline, J., Blanford, G., Brown, M., Burtraw, D., Domeshek, M., Farbes, J., & Zhao, A. (2023). Emissions and energy impacts of the inflation reduction act. Science, 380(6652), 1324–1327. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adg3781

- Bolderdijk, J. W., Steg, L., Geller, E. S., Lehman, P. K., & Postmes, T. (2013). Comparing the effectiveness of monetary versus moral motives in environmental campaigning. Nature climate change, 3(4), 413–416. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1767

- Bouman, T., Verschoor, M., Albers, C. J., Böhm, G., Fisher, S. D., Poortinga, W. & Steg, L. (2020). When worry about climate change leads to climate action: How values, worry and personal responsibility relate to various climate actions. Global Environmental Change, 62, 102061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102061

- Brosch, T., & Steg, L. (2021). Leveraging emotion for sustainable action. One Earth, 4(12), 1693–1703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2021.11.006

- Climate Leadership Council. (2024). Economists’ statement on carbon dividends. Retrieved May 5, 2024, from https://clcouncil.org/economists-statement/

- Cologna, V., & Siegrist, M. (2020). The role of trust for climate change mitigation and adaptation behaviour: A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 69, 101428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101428

- Dasandi, N., Graham, H., Hudson, D., Jankin, S., VanHeerde Hudson, J., & Watts, N. (2022). Positive, global, and health or environment framing bolsters public support for climate policies. Communications Earth & Environment, 3(1), 239. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00571-x

- The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (2024). Climate change and human health. https://www.epa.gov/climateimpacts/climate-change-and-human-health

- Frazin, R. (2024). How a trump presidency could threaten biden’s signature climate achievement. The hill. Retrieved March 20, 2024, from https://thehill.com/policy/energy-environment/4543117-trump-biden-inflation-reduction-act-hamper-climate-gains/

- Goldberg, M. H., Gustafson, A., Ballew, M. T., Rosenthal, S. A., & Leiserowitz, A. (2021). Identifying the most important predictors of support for climate policy in the United States.Behavioural Public Policy, 5(4), 480–502.

- Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A., Bain, P. G., & Fielding, K. S. (2016). Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change. Nature Climate Change, 6(6), 622–626. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2943

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2023). AR6 synthesis report: Climate change 2023. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle/

- Jamieson, K. H. (2017). The need for a science of science communication: Communicating science’s values and norms. In Kathleen Hall Jamieson, Dan M. Kahan, &Dietram A. Scheufele (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the Science of Science Communication, Oxford Library of Psychology (2017; online edn, Oxford Academic, 6 June 2017). Retrieved June 4, 2024 from https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190497620.013.2

- Jamieson, K. H., Romer, D., Jamieson, P. E., Winneg, K. M., & Pasek, J. (2021). The role of non–COVID-specific and COVID-specific factors in predicting a shift in willingness to vaccinate: A panel study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 118(52), e2112266118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2112266118

- Kotcher, J., Maibach, E., Montoro, M., & Hassol, S. J. (2018). How Americans respond to information about global warming’s health impacts: Evidence from a national survey experiment. GeoHealth, 2(9), 262–275. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GH000154

- Li, N., & Yi-Fan Su, L. (2018). Message framing and climate change communication: A meta-analytical review. Journal of Applied Communications, 102(3), 4.

- Mendoza-Vasconez, A. S., McLaughlin, E., Sallis, J. F., Maibach, E., Epel, E., Bennett, G., & Dietz, W. H. (2022). Advocacy to support climate and health policies: Recommended actions for the society of behavioral medicine. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 12(4), 535–542. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibac028

- Meyer, R. (2022). The best evidence yet that the climate Bill Will Work. The Atlantic. August 3, 2022.

- Myers, T. A., Kotcher, J., Stenhouse, N., Anderson, A. A., Maibach, E., Beall, L., & Leiserowitz, A. (2017). Predictors of trust in the general science and climate science research of U.S. federal agencies. Public Understanding of Science, 26(7), 843–860. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662516636040

- Myers, T. A., Nisbet, M. C., Maibach, E. W., & Leiserowitz, A. A. (2012). A public health frame arouses hopeful emotions about climate change. Climatic Change, 113, 1105–1112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-012-0513-6

- Ng, T. W., & Feldman, D. C. (2012). Employee voice behavior: A meta‐analytic test of the conservation of resources framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(2), 216–234. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.754

- Rocque, R. J., Beaudoin, C., Ndjaboue, R., Cameron, L., Poirier-Bergeron, L., Poulin-Rheault, R. A., & Witteman, H. O. (2021). Health effects of climate change: An overview of systematic reviews. British Medical Journal Open, 11(6), e046333. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046333

- Romer, D., Winneg, K. M., Jamieson, P. E., Brensinger, C., & Jamieson, K. H. (2022). Misinformation about vaccine safety and uptake of COVID-19 vaccines among adults and 5–11-year-olds in the United States. Vaccine, 40(45), 6463–6470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.09.046

- Sheeran, P., Maki, A., Montanaro, E., Avishai-Yitshak, A., Bryan, A., Klein, W. M., & Rothman, A. J. (2016). The impact of changing attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy on health-related intentions and behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 35(11), 1178. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000387

- Smith, N., & Leiserowitz, A. (2014). The role of emotion in global warming policy support and opposition. Risk Analysis, 34(5), 937–948.

- van Valkengoed, A., & Steg, L. (2019). The psychology of climate change adaptation. Cambridge University Press.

- Van Valkengoed, A. M., Steg, L., & Perlaviciute, G. (2021). Development and validation of a climate change perceptions scale. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 76, 101652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101652

- World Health Organization. (2023). Climate Change: Key facts. Retrieved October 10, 2023, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health