Abstract

This study investigates the role of dynamic fear in the effectiveness of communicating health threats (i.e. fear appeals) of ground-level ozone among Chinese citizens. An online survey revealed that fear appeal messages effectively enhance the audience’s risk perceptions, efficacy beliefs, and acceptance of the message. Crucially, dynamic fear reduction process positively predicts engagement in protective behaviors (i.e. danger control process) and negatively predicts engagement in fear control processes, such as message denial. Presenting severity before susceptibility resulted in a more positive attitude toward the message recommendation. These findings highlight that communicating health-threats about climate pollution is effective in raising awareness and motivating protective behaviors. Furthermore, our study underscores the importance of dynamic fear, specifically fear reduction, in increasing fear appeals’ effectiveness in communicating climate issues from a health perspective.

While climate change as a term describes the overall anthropogenic influence on Earth’s ecosystems through the burning of fossil fuels and the increase of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, its effects are felt distinctly at the local level. Urban residents, for example, frequently encounter greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and nitrogen dioxide from vehicles, as well as ground-level ozone—a pollutant formed when fossil fuel emissions react with sunlight and heat (Environmental Protection Agency EPA, Citation2023). Although a shift away from fossil fuels should reduce emissions, long-lived greenhouse gases ensure that warming and its consequences, like increased ground-level ozone, will persist (Buis, Citation2019). Thus, the problem of ground level ozone will remain a challenge for densely populated cities to manage, particularly as the average temperature of the Earth rises: more heat predicts the creation of more ground level ozone (American Lung Association, Citation2023).

China’s challenge with ozone pollution is exacerbated by its densely populated cities. As a potent oxidant, ground-level ozone poses significant risks to human health. Despite ongoing efforts to mitigate its impact, there is a significant gap in public awareness and understanding of ozone pollution (Li et al., Citation2021; Lu et al., Citation2018). This gap hinders effective engagement and response to the pollution, underscoring the need for improved communication strategies that can enhance public knowledge and support for environmental health initiatives.

As a commonly used technique, fear appeal has been studied and applied in various contexts for decades. Early fear appeal theories placed fear in the driver’s seat, but more recent theories have shifted toward emphasizing cognitive processes rather than emotional ones. While fear appeal theories highlight the important role of dynamic fear, most empirical research on fear appeals fails to capture the nuanced and dynamic processes of individuals’ fear in response to fear appeals. The primary objective of this project is to reposition fear as a central element in our study of fear appeals, particularly in the context of ground-level ozone pollution among Chinese citizens. We aim not only to determine if fear appeals are effective in this novel context, but more crucially, to understand why and how they influence behavior and to elucidate the role of dynamic fear, as emphasized in early fear appeal theories. It takes an international perspective and sheds light on theories and practices surrounding fear appeal in both health and environmental communication domains.

Fear Appeal

Fear appeal, sometimes labeled as threat appeal, is a common tactic in health and risk communication. It involves presenting threats and their unfavorable consequences—typically via vivid language and graphic images—to motivate audiences to accept the opinions expressed in persuasive messages (Hovland et al., Citation1953; Witte, Citation1992). Theories and empirical evidence accumulated over decades (Dillard, Li, & Huang, Citation2017, Citation2017b; Hovland et al., Citation1953; Witte, Citation1992) suggest that a fear appeal message should comprise two key components: a danger component and an action component. The danger component should articulate the negative consequences of the threat (i.e., severity) and the extent to which individuals are likely to be affected by it (i.e., susceptibility). The action component should present a recommended action or solution, emphasize an individual’s capacity to protect themselves from the danger (i.e., self-efficacy) and the effectiveness of the recommended action in averting the threat’s negative consequences (i.e., response efficacy).

A series of meta-analyses on the effectiveness of fear appeals consistently suggested that fear appeals can lead to behavioral change through eliciting fear and cognitive processes like perceived threat and efficacy beliefs (e.g., Bigsby & Albarracín, Citation2022; De Hoog et al., Citation2007; Tannenbaum et al., Citation2015; Witte & Allen, Citation2000). Several studies have tested the order effect of major fear appeal components. For example, Moussaoui et al. (Citation2021) found that compared to the “threat only” version, “threat plus coping” or the reversed “coping plus threat” versions of fear appeals did not lead to significantly different persuasive outcomes, although they noted that this null finding might be due to insufficient statistical power. Other studies suggested that the optimal order of these two components depend on factors such as the threat level contained in the message and the predisposition of the audience (Brown & West, Citation2015; Keller, Citation1999). To date, no specific guidance has been provided on the sequencing—the order in which minor subcomponents are presented—within each of these two components (Dillard, Li, & Huang, Citation2017, Citation2017b; Hovland et al., Citation1953; Witte, Citation1992).

Within environmental communication, the efficacy of fear messages has been considered, often with the acknowledgment that tipping too far over into fear (e.g., fatalism) is a real concern given the scale of addressing climate change (Mayer & Smith, Citation2019). However, in research conducted with Canadian citizens, data suggested that threatening loss messages that included an efficacy statement resulted in the most effective message strategy to produce the highest pro-policy attitudes and people’s willingness to pay for policies that reduce Canada’s carbon emissions (Armbruster et al., Citation2022). The research team proposed that using a “loss-frame”—a common framing technique in communication research that emphasizes what will be lost if something is not done— aligns theoretically with the use of fear appeals given that loss frames tend to generate more fear and perceived threat than positive frames (Armbruster et al., Citation2022, p. 2). Such finding is consistent with recent meta-analyses that show fear appeals have stronger impact on persuasive outcomes when they contain efficacy statements (Bigsby & Albarracín, Citation2022; Tannenbaum et al., Citation2015).

In research focusing on fear appeals and climate change in the Asian context, there is evidence that inspiring too much fear, as noted previously, can actually lead to more defensive behavior (e.g., counter-arguing) instead of pro-environmental behavioral intentions (Chen, Citation2016). That being said, the researcher noted that in instances where individuals also have high collective response efficacy, being exposed to the high fear condition did in fact result in higher pro-environmental behavioral intentions. Other work has suggested that increasing perceived threat and perceived efficacy through a fear appeal positively predicted not only climate related behavioral intentions, but also the systematic route of information processing (Sarrina & Huang, Citation2020). To date, it does not appear that any researchers have tested the efficacy of fear appeals in increasing persuasive outcomes regarding ground-level ozone, but given the previous scholarship that suggests fear appeals play a role in environmental communication, it seems logical to test fear appeals for ground-level ozone.

We hypothesize:

H1: Individuals exposed to the fear appeal message will demonstrate higher (a) perceived severity, (b) perceived susceptibility, (c) self-efficacy, (d) response efficacy, (e) attitude toward the recommendation, and (f) intention to follow the recommendation, compared to those who were not exposed to such a message.

In addition, we pose the following research question due to the absence of specific theoretical or empirical guidance:

RQ1: Does the sequencing of severity and susceptibility in the message influence individuals’ risk perceptions, peak fear, and persuasive outcomes (i.e., attitude toward the recommendation and intention to follow the recommendation)?

Fear Appeal Theories

Despite the widespread use of fear appeals in different contexts, scholars have developed various theories to elucidate the mechanisms that underpin the effectiveness of fear appeals.

Hovland et al. (Citation1953) proposed a Drive theory, in which they suggested that intensely disturbing emotions, such as fear, have the functional properties of a drive. Once activated, this motivates trial-and-error behaviors that could reduce such tension. Therefore, for a threat appeal message to be effective, it needs to a) elicit sufficient emotional tension to constitute a drive state, and b) offer recommendations that could help reduce such tension.

Another line of theories places greater emphasis on individuals’ cognitive perceptions rather than emotional responses. Leventhal (Citation1970) developed the Parallel Process Model (PPM), proposing that in response to threat appeals, individuals may engage in one of two control processes: danger control processes, which involve strategizing to control the threat, or fear control processes, where mental resources are allocated to managing feelings of fear. Similarly, Rogers (Citation1983) in his Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) emphasized the importance of cognitive mediating processes within the context of fear appeals. According to PMT, individuals engage in both threat appraisal and coping appraisal, where they assess maladaptive and adaptive responses, respectively.

Although the two theories highlight key cognitive processes in self-protective decision-making, Witte (Citation1992) critiqued their lack of precision. The PPM does not specify when individuals will choose danger control over fear control. PMT, meanwhile, also faces empirical inconsistencies and does not clarify how separate appraisal processes collectively predict protection motivation. Consequently, while these theories explain linear results in many studies, they struggle with boomerang or curvilinear findings. In addition, Witte also pointed out that in both of these two theories, fear has been “given a backseat role” (Witte, Citation1992, p. 335).

To overcome these limitations, Witte (Citation1992) introduced the Extended Parallel Process Model (EPPM). This model suggests that when facing a threat, individuals first appraise the threat. A low perceived threat diminishes their motivation to further process the message. Conversely, a moderate to high perceived threat triggers fear, activating the secondary appraisal process. If individuals believe they can effectively mitigate the threat, they engage in danger control. However, if they perceive the threat as severe but doubt their efficacy to counter it, they resort to fear control. According to Witte, the presence of a threatening message triggers a threat appraisal, leading to fear. If efficacy beliefs are low, this fear intensifies, activating defensive motivations due to the overwhelming fear. Conversely, when individuals possess strong efficacy beliefs, the aroused fear actually enhances their perception of the threat, indirectly leading to adaptive outcomes. Although PPM and EPPM theorized danger control and fear control as incompatible “either-or” mechanisms, more recent empirical evidence has revealed the possibility that these two mechanisms could coexist (e.g., Moussaoui et al., Citation2021; Shen & Coles, Citation2015).

In summary, while early fear appeal theories positioned fear as central to motivating behavior change and emphasized the dynamic pattern of fear responses, its role was subsequently downplayed in later models. A key reason for this evolution is the empirical rejection of the drive theory and the inconsistent predictive power of fear observed in empirical studies (Beck & Frankel, Citation1981; Witte, Citation1992).

However, Dillard, Li, & Huang, (Citation2017, Citation2017b); Shen & Dillard, (Citation2014) have noted that the lack of empirical support for the drive theory is largely due to the inadequate measurement of fear in existing research. According to Dillard, existing fear appeal research commonly measures fear as a static state after individuals complete reading the entire fear appeal message, and such approach fails to capture how individuals’ fear responses change over time, which is essential for understanding the drive theory’s predictions. The drive theory posits that, typically, fear peaks after individuals process the threatening part of the message and then decreases following exposure to the solution. Therefore, it is the dynamic change of fear—the rise and fall—that predicts individuals’ likelihood of following the message’s recommendations, rather than any static fear level.

Empirical studies provide insights into this prediction. Rossiter and Thornton (Citation2004), in their analysis of the fear patterns in anti-speeding TV commercials and their effects, found that a pattern of fear followed by relief reduced young drivers’ speed choices, while fear without subsequent relief initially increased speed choices. Shen and Dillard (Citation2014) observed that an inverted-U shape of fear predicted individuals’ attitudes toward receiving the influenza vaccine, encapsulating their finding with the statement, “persuasion is the result of a rise, then offset in fear” (Shen & Dillard, Citation2014, p. 105). In a similar vein, Dillard, Li, and Huang (Citation2017, Citation2017b) identified the inverted-U shaped fear response in studies related to colorectal cancer screening, concluding that in both cases, this fear pattern significantly influenced people’s intentions to undergo a colonoscopy.

This empirical evidence consistently revealed that individuals’ fear responses to fear appeal messages are indeed dynamic rather than static and play a critical role in determining persuasive outcomes, providing support for Drive theory. Since fear is an unpleasant affective state, behaviors or actions that significantly relieve this tension are perceived as rewarding and are more likely to be adopted. Based on the above discussion, we hypothesize that

H2: The fear measured after the threat component of the message (peak fear) is significantly higher compared to the baseline fear level; and the fear measured after the action component of the message (end fear) is significantly lower than the peak fear.

H3: Greater fear reduction from peak fear to end fear will be positively predictive of message acceptance, including individuals’ attitude toward the message recommendation and their intention to follow the recommendation.

Although this body of work supports the drive theory and emphasizes the critical role of fear in fear appeals, it primarily focuses on the impact of fear reduction on the specific message recommendation. However, communication scholars have highlighted that the danger control process can encompass a range of behaviors (e.g., information seeking) far more extensive than a single message recommendation (Rimal & Real, Citation2003). Hovland et al. (Citation1953) similarly noted that fear acts as a drive, motivating trial-and-error behaviors: any method that successfully alleviates such negative emotional tension will be learned and reinforced. When individuals encounter a fear appeal message with just one recommended action, they may broaden their approach, seeking additional information and contemplating alternative self-protection strategies. Consequently, we hypothesize:H4: A greater reduction in fear from its peak to its end will positively predict individuals’ engagement in the danger control process.

The link between fear reduction and defensive reactions has not been tested with dynamic measures of fear either. Hovland et al. (Citation1953) theorized in the drive theory that when emotional tension is strongly aroused and fails to be reduced, defensive reactions might occur. Similarly, Leventhal (Citation1970) identified fear control as one of two possible control processes in which individuals can engage, according to PPM. However, these propositions have not yet been empirically tested using dynamic measures of fear. Drawing from the drive theory’s implications and PPM’s proposition, we hypothesize that:H5: A greater reduction in fear from its peak to its end will be inversely associated with individuals’ engagement in the fear control process.

Method

Overview

An online between-subjects (Fear appeal message vs. no message) experiment was conducted through the Qualtrics panel. Participants from one hundred and thirteen large cities, each with a population of over 1 million in mainland China, were recruited and offered cash incentives. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board before the start of data collection. The questionnaire was hosted on Qualtrics.

Upon completion of the consent form, participants reported their baseline affective states (e.g., fear) at the moment before they were randomly assigned to conditions. Three-fourths of participants were then randomly assigned to the experimental conditions where they were instructed to read a fear appeal message developed for this study. Their fear levels were measured after they viewed the threat and action part of the message, respectively. After reading the message, participants completed measures for a host of variables. The remaining one fourth of the participants were assigned into a control condition where they were not exposed to any message and only completed the same questionnaire. The questionnaire and the stimuli were presented in Chinese. A total of 2,573 participants provided complete and valid responses. The demographic information of the sample is summarized in .

Table 1. Socio-demographics characteristics of participants

Stimuli

The current study focuses on a relatively understudied environment issue in the literature: ground level ozone pollution.

Guided by fear appeal theories, the authors created four messages featuring texts and infographics portraying ground level ozone pollution as a serious (i.e., severity) and prevalent (i.e., susceptibility) environment problem in China and recommendation for protection from the negative health impacts of ground level ozone pollution (i.e., self- and response efficacy). The texts and infographics across the four messages were slightly different (e.g., the order of presentation of severity and susceptibility information, the layout and design of infographics) to ensure message heterogeneity (Slater et al., Citation2015). With multiple different messages, this study was able to rule out potential confounding effects of message features. Each message was about 500 words, along with four infographics (see Supplemental Materials). The messages were based on existing literature on ground level ozone pollution and its health risk. An expert in climate science was consulted to make sure the scientific quality of the messages.

Measures

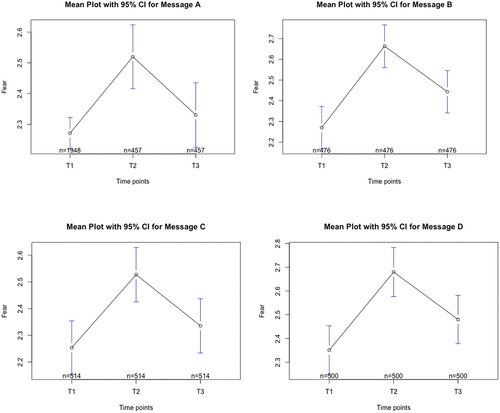

Fear was measured with two items. Participants were asked to rate how much they felt 1) fearful and 2) scared at the moment on a 5-point scale (1 = None of this feeling, 5 = A lot of this feeling). Fear was measured at three time points: prior to message exposure, after exposure to the threat component, and after exposure to the action component. Responses were averaged for an index for each time point (T1: M = 2.29, SD = 1.16, r = .79; T2: M = 2.60, SD = 1.16, r = .89; T3: M = 2.40, SD = 1.15, r = .89). The fear reduction was calculated by subtracting the end fear at T3 from the peak fear at T2.

Attitude toward recommendation for protection. Participants were asked to rate “For me to adjust my outdoor activities Footnote1based on the ground level ozone pollution situation is … ” on seven 5-point bipolar semantic scales (e.g., unattractive-attractive; bad-good). Higher scores indicated a more positive attitude toward recommendation for protection. Scores reported by the participants were averaged for an index (M = 3.88, SD = .84, α = .89).

Intention toward recommendation for protection. Participants were asked to estimate “What is the likelihood that you will adjust your outdoor activities based on the ground level ozone pollution situation in the future?” on a slider scale from 0% to 100%. Higher scores indicated a greater behavioral intention toward recommendation for protection (M = 74.40, SD = 19.38).

Perceived severity of ground level ozone pollution was measured using four questions. A sample item was “Ground level ozone pollution issues are severe in the city I live in.” Participants rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 5 = Strongly agree, M = 4.08, SD = .57, α = .71).

Perceived susceptibility of ground level ozone pollution was measured using four questions (M = 3.48, SD = 1.00, α = .90). A Sample item was “To what extent do you think ground level ozone pollution is dangerous to you and your family?” Participants rated each item on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all, 5 = Very much so).

Self-efficacy was measured using four questions (M = 3.41, SD = .63, α = .82) adapted from Xue et al. (Citation2016). A sample item was “To what extent do you feel equipped to adjust your outdoor activities based on the Ground level ozone pollution situation?” Participants rated each item on a 5-point scale (1 = Not at all, 5 = Very much so).

Response efficacy was measured using four questions (M = 3.90, SD = .60, α = .74). A sample item was “Adjusting my outdoor activities based on the Ground level ozone pollution situation is effective in protecting myself and family members from being hurt by air pollution.” Participants rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 5 = Strongly agree).

Danger control was measured with four questions adapted from Xue et al. (Citation2016) with a sample item being “To what extent do you feel like the message motivates you to take action to address ground level ozone pollution?” Participants rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all, 5 = Very much, M = 3.93, SD = .77, α = .86).

Fear control was measured with three questions adapted from Xue et al. (Citation2016) (M = 2.57, SD = 1.23, α = .86). A sample item was “To what extent do you perceive the message to encourage denial?” Participants rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all, 5 = Very much).

Analysis Strategy

H1 and RQ1 were tested using Welch Two Sample t-tests. H2 was tested using a paired t-test. H3 through H5 were tested using ordinary least square (OLS) linear regression. Analyses were performed using the R platform for statistical computing version 4.3.0.

Results

H1 predicted that individuals exposed to the fear appeal message would demonstrate higher risk perceptions, efficacy beliefs, and message acceptance, compared to those who were not exposed to such a message. As shown in , Welch Two Sample t-test results showed that individuals who were exposed to the fear appeal message reported a higher level of perceived severity, perceived susceptibility, self-efficacy, response efficacy, attitude toward the recommendation, and intention to follow the message recommendation (ts range from 3.71 to 5.64, ps < .01). Results supported H1.

Table 2. Mean comparisons between individuals exposed to the message and those who were not

RQ1 aims to explore whether the sequencing of severity and susceptibility in the message influences individuals’ risk perceptions, peak fear, and persuasive outcomes. Independent sample t-test results revealed that the order of presenting severity or susceptibility in the threat component had no significant impact on individuals’ risk perceptions, peak fear, or intention to follow the message recommendation (ts range from −.43 to .21, ps range from .40 to .67). However, when severity was presented before susceptibility, individuals reported a marginally higher positive attitude (M = 3.95vs. 3.88) toward the message recommendation (t = 1.75, two-sided p = .08).

H2 predicted that peak fear would be significantly higher compared to the baseline fear level, and end fear would be significantly lower than the peak fear. Paired sample t-test results supported this hypothesis: compared to their baseline fear level (M = 2.29, SD = 1.16), participants reported a significantly higher level of peak fear (M = 2.60, SD = 1.16) after exposure to the threat component, t (1947) = −17.60, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .19. Following exposure to the efficacy component of the message, their end fear level dropped significantly (M = 2.40, SD = 1.15), t (1946) = 11.79, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .12. displays the dynamic fear responses for each message group.

Figure 1. Dynamic fear responses among four message groups.

H3 posited that the reduction of fear from the peak to the endpoint would positively influence persuasive outcomes, such as attitude and intention toward the recommendation. Simple linear regression results showed that fear reduction positively predicts individuals’ attitude toward the message recommendation, b = .07, SE = .025, t (1921) = 2.83, p = .005. However, it did not significantly predict individuals’ intentions to follow the message recommendation, b = .66, SE = .57, t (1941) = 1.15, p = .25. In line with the reasoned action approach (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1977), a mediation test using PROCESS (Hayes, Citation2013) was conducted to examine if attitude mediates the relationship between fear reduction and intention. The results revealed a significant indirect effect of fear reduction on intention through attitude, estimate = .54, SE = .19, bootstrapped 95% CI: [.17, .92]. These findings confirm H3, demonstrating that individuals’ reduction in fear from the peak to the end point positively influences their attitude toward the recommendation, which subsequently positively affects their intention to follow it.

H4 and H5 posited that a greater reduction in fear from its peak to its end would positively predict individuals’ danger control and negatively predict fear control. Simple linear regression supported these hypotheses. Fear reduction was found to positively predict danger control, b = .05, SE = .02, t (1944) = 2.09, p = .04, and it negatively predicted fear control, b = −.11, SE = .04, t (1921) = −2.91, p = .004.

Discussion

This study surveyed Chinese citizens residing in larger cities to understand the effectiveness of fear appeals in communicating about ground-level ozone pollution. Our results suggest that fear appeals can be an effective strategy in enhancing individuals’ engagement in self-protective behaviors.

Following more recent investigations around fear appeals (Dillard, Li, & Huang, Citation2017, Citation2017b; Shen & Dillard, Citation2014), we conceptualize fear as a dynamic process. Specifically, we measured participants’ fear at three time points: before exposure to the message (baseline fear), after exposure to the threat component (peak fear), and immediately following exposure to the action component (end fear). The results indicated that individuals’ peak fear levels were significantly higher than their baseline fear levels. More importantly, upon presentation with the action component, their fear levels dropped significantly. Echoing the findings of Dillard and colleagues (Dillard, Li, & Huang, Citation2017, Citation2017b), it is not the intensity of peak or end fear that predicts message acceptance but rather the dynamic fear process. In line with the drive theory, we found that the reduction in fear from the peak to the end point positively predicted individuals’ attitudes toward our recommendation, which, in turn, positively influenced their intention to adhere to it.

It is worth noting that the analytical approach adopted in this project differs from Dillard et al.’s approach. They used Latent Growth Curve (LGC) modeling to test the complete inverted-U shaped fear curve’s effect on persuasion, while we chose to use the simple reduction of fear (peak fear minus end fear) to predict persuasion. In the context of environmental communication, when the audience already has a good understanding of the severity and susceptibility of air pollution issues in China, the extent to which a fear appeal message could further increase their fear is not as critical as how much the message could reduce their fear. Theoretically speaking, in alignment with prominent fear appeal theories such as drive theory and EPPM, we believe the reduction of fear plays a more critical role than the whole inverted-U shaped fear curve in determining the audience’s responses. Methodologically speaking, the simple operationalization of the reduction of fear is much more feasible than LGC, which can be more easily adopted by communication practitioners in testing the effectiveness of their communication efforts.

Additionally, our study expands the investigation by examining other self-protective behaviors beyond the recommended action and defensive reactions. We found that the decrease in fear not only led to greater acceptance of the message but also to increased engagement in the danger control process, such as information seeking. Although the drive theory posits that failure to reduce emotional tension would lead to defensive reactions, the idea was not properly tested with dynamic data of fear. We discovered that when peak fear does not subside, individuals engage in more fear control, such as criticizing or denying the message, providing empirical evidence that the lack of fear reduction can activate fear control processes.

The project also contributes to fear appeal theories by clarifying the circumstances that determine individuals’ likelihood of engaging in danger control and fear control processes. Our research has made a significant advancement by putting the fear back in fear appeals and identifying a critical factor: the reduction of fear. If fear is reduced following a fear appeal, individuals engage in more danger control; if fear remains high, fear control predominates. This distinction provides a clearer framework for predicting the outcomes of fear appeals and enhances our understanding of the emotional pathways involved.

Practical Implications

Our research has demonstrated that fear appeals, when properly utilized, can effectively communicate environmental issues. In line with established fear appeal theories and empirical evidence, an effective fear appeal message should initially outline the severity of the environmental threat and the individual’s susceptibility to this threat. It should then provide concrete actions that individuals can take to protect themselves from harm. Our findings additionally suggest that presenting the severity component before the susceptibility component may result in more persuasive outcomes. To environmental communication scholars who are concerned about triggering excessive fear, we offer a straightforward recommendation: intense fear can be constructively reduced by including in the communication an actionable recommendation that effectively safeguards individuals from the perceived danger. This approach encourages individuals to engage in danger control rather than fear control.

Limitations and Future Research

This study has some limitations. First, we tested fear appeal messages only among Chinese citizens residing in large cities. It remains uncertain whether individuals in smaller cities, rural areas, or citizens of other countries would react similarly to these messages. Secondly, the survey was conducted entirely online. Although we implemented attention checks throughout the questionnaire, we cannot guarantee that all participants were fully attentive to the message and the survey questions. Additionally, only three items were used to measure defensive reactions to avoid overburdening participants, but these measures might not capture the complexity of the concept comprehensively. Future research can benefit from measuring different types of defensive reactions more thoroughly and examining their relationships with dynamic fear. Investigating the extent to which cognitive processes contribute to these dynamics and how they interact with emotions to influence decision-making also warrants further attention. Some measurement items focused on participants’ perceptions of protecting themselves and their family members. Since individuals may have different perceptions regarding self-protection versus protecting others, future research could benefit from addressing these questions separately. While the current study is limited to the issue of ground-level ozone in China, future research can benefit by expanding the scope to include various international contexts and topics, such as other environmental issues and political threats, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of the subject matter.

Conclusion

This project utilized extensive survey data to investigate the effectiveness of fear appeals in environmental communication among Chinese citizens and to understand the mechanisms underlying their effectiveness. In support of the original drive theory, our findings indicate that fear appeals must first generate sufficient fear and then provide concrete and practical recommendations to alleviate this fear. It is the reduction of fear that effectively drives individuals’ intentions to accept the message’s recommendations and engage more in the danger control process and less in the fear control process. This project makes valuable theoretical contributions by highlighting the role of dynamic emotional processes and offers practical guidance to communication practitioners.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (3.1 MB)Acknowledgments

This work was funded by U.S. Department of State through award SCH50022CA0073.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2024.2361356.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 Outdoor activities refer to leisure pursuits such as jogging or walking the dog, rather than obligatory tasks like going to work. Complete messages and visuals are available in the supplementary materials.

References

- American Lung Association. (2023, October 25). Ozone. https://www.lung.org/clean-air/outdoors/what-makes-air-unhealthy/ozone

- Armbruster, S. T., Manchanda, R. V., & Vo, N. (2022). When are loss frames more effective in climate change communication? An application of fear appeal theory. Sustainability, 14(12), 10–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127411

- Beck, K. H., & Frankel, A. (1981). A conceptualization of threat communications and protective health behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly, 44(3), 204–217. https://doi.org/10.2307/3033834

- Bigsby, E., & Albarracín, D. (2022). Self-and response efficacy information in fear appeals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Communication, 72(2), 241–263. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqab048

- Brown, S. L., & West, C. (2015). Sequencing the threat and recommendation components of persuasive messages differentially improves the effectiveness of high‐and low‐distressing imagery in an anti‐alcohol message in students. British Journal of Health Psychology, 20(2), 324–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12103

- Buis, A. (2019, October 9). The atmosphere: Getting a handle on carbon dioxide. NASA: Global climate change, vital signs of the planet. https://climate.nasa.gov/news/2915/the-atmosphere-getting-a-handle-on-carbon-dioxide/

- Chen, M. F. (2016). Impact of fear appeals on pro-environmental behavior and crucial determinants. International Journal of Advertising, 35(1), 74–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2015.1101908

- De Hoog, N., Stroebe, W., & De Wit, J. B. (2007). The impact of vulnerability to and severity of a health risk on processing and acceptance of fear-arousing communications: A meta-analysis. Review of General Psychology, 11(3), 258–285. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.11.3.258

- Dillard, J. P., Li, R., & Huang, Y. (2017). Threat appeals: The fear-persuasion relationship is linear and curvilinear. Health Communication, 32(11), 1358–1367. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2016.1220345

- Dillard, J. P., Li, R., Meczkowski, E., Yang, C., & Shen, L. (2017). Fear responses to threat appeals: Functional form, methodological considerations, and correspondence between static and dynamic data. Communication Research, 44(7), 997–1018. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650216631097

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (2023, June 2). Ground-level ozone basics. https://www.epa.gov/ground-level-ozone-pollution/ground-level-ozone-basics

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1977). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research.

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

- Hovland, C. I., Janis, I. L., & Kelley, H. H. (1953). Communication and persuasion.

- Keller, P. A. (1999). Converting the unconverted: The effect of inclination and opportunity to discount health-related fear appeals. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(3), 403–415. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.84.3.403

- Leventhal, H. (1970). Findings and theory in the study of fear communications. InL. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 5, pp. 119–186). Academic Press.

- Li, A., Zhou, Q., & Xu, Q. (2021). Prospects for ozone pollution control in China: An epidemiological perspective. Environmental Pollution, 285, 117670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117670

- Lu, X., Hong, J., Zhang, L., Cooper, O. R., Schultz, M. G., Xu, X., Wang T, Gao M, Zhao Y, & Zhang, Y. (2018). Severe surface ozone pollution in China: A global perspective. Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 5(8), 487–494. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.8b00366

- Mayer, A., & Smith, E. K. (2019). Unstoppable climate change? The influence of fatalistic beliefs about climate change on behavioural change and willingness to pay cross-nationally. Climate Policy, 19(4), 511–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2018.1532872

- Moussaoui, L. S., Claxton, N., & Desrichard, O. (2021). Fear appeals to promote better health behaviors: An investigation of potential mediators. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 9(1), 600–618. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2021.1947290

- Rimal, R. N., & Real, K. (2003). Perceived risk and efficacy beliefs as motivators of change: Use of the risk perception attitude (RPA) framework to understand health behaviors. Human Communication Research, 29(3), 370–399. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/29.3.370

- Rogers, R. W. (1983). Cognitive and physiological processes in fear appeals and attitude change: A revised theory of protection motivation. In J. T. Cacioppo & R. E. Petty (Eds.), Social Psychology: A Source Book, 153–176. The Guilford Press.

- Rossiter, J. R., & Thornton, J. (2004). Fear‐pattern analysis supports the fear‐drive model for antispeeding road‐safety TV ads. Psychology & Marketing, 21(11), 945–960. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20042

- Sarrina, S.-C., & Huang, L.-M. S. (2020). Fear appeals, information processing, and behavioral intentions toward climate change. Asian Journal of Communication, 30(3–4), 242–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2020.1784967

- Shen, L., & Coles, V. (2015). Fear and psychological reactance: Between- vs. within-individuals perspectives. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 223(4), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000224

- Shen, L., & Dillard, J. P. (2014). Threat, fear, and persuasion: Review and critique of questions about functional form. Review of Communication Research, 2, 94–114. https://doi.org/10.12840/issn.2255-4165.2014.02.01.004

- Slater, D. M., Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2015). Message variability and heterogeneity: A core challenge for communication research. Annals of the International Communication Association, 39(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2015.11679170

- Tannenbaum, M. B., Hepler, J., Zimmerman, R. S., Saul, L., Jacobs, S., Wilson, K., & Albarracín, D. (2015). Appealing to fear: A meta-analysis of fear appeal effectiveness and theories. Psychological Bulletin, 141(6), 1178. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039729

- Witte, K. (1992). Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Communications Monographs, 59(4), 329–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759209376276

- Witte, K., & Allen, M. (2000). A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Education & Behavior, 27(5), 591–615. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019810002700506

- Xue, W., Hine, D. W., Marks, A. D., Phillips, W. J., Nunn, P., & Zhao, S. (2016). Combining threat and efficacy messaging to increase public engagement with climate change in Beijing, China. Climatic Change, 137(1–2), 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1678-1