Abstract

Society is at an inflection point—both in terms of climate change and the amount of data and computational resources currently available. Climate change has been a catastrophe in slow motion with relationships between human activity, climate change, and the resulting effects forming a complex system. However, to date, there has been a general lack of urgent responses from leaders and the general public, despite urgent warnings from the scientific community about the consequences of climate change and what can be done to mitigate it. Further, misinformation and disinformation about climate change abound. A major problem is that there has not been enough focus on communication in the climate change field. Since communication itself involves complex systems (e.g. information users, information itself, communications channels), there is a need for more systems approaches to communication about climate change. Utilizing systems approaches to really understand and anticipate how information may be distributed and received before communication has even occurred and adjust accordingly can lead to more proactive precision climate change communication. The time has come to identify and develop more effective, tailored, and precise communication for climate change.

We put together this Special Issue on Climate Change Communication in large part because our society is at an inflection point. Climate change has been brewing for several decades affecting human, societal, and environmental ecosystems in complex and detrimental ways. Further, the relationships between human activity, climate change, and the resulting effects form a complex system. Despite urgent warnings from the scientific community about the dire consequences of climate change and what humans can do to mitigate it, there has been a lack of urgent responses from political and business leaders, as well as much of the general public. In fact, misinformation and disinformation about climate change have abounded [e.g., played a critical role in moderating the much needed response to reduce greenhouse gasses (GHG) emissions], often further propagated by some political and business leaders. A major problem is that there hasn’t been enough focus on communication in the climate change arena (especially in audiences with different morals, beliefs, societal, cultural, and educational experiences) compared to other fields and sectors. Since communication itself involves complex systems, there is a need for more systems approaches to climate change communication. As will be detailed below, such systems approaches can lead to more proactive precision communications about climate change that are needed to combat this global catastrophe in slow motion.

Climate Change Is a Catastrophe in Slow Motion

As we move through our daily lives, it is easy to forget that climate change is already upon us, unfolding as a slow-motion catastrophe. Most extreme weather events of the past decade are dismissed as mere heatwaves, hurricanes, or storms. Media attention is always on the devastation and cleanup efforts, and talking heads focus on the cleanup costs and timelines. Then, as fast as the event moves in, it fades away from our consciousness as we hastily move on to the next topic du-jour. The idea of climate change is always abstract, just below the surface, and never truly visible. However, for many New Yorkers, that reality came into stark view in June 2023 when wildfire smoke from Canada blanketed much of the eastern seaboard and stretched as far as the Midwest. The events that unfurled over the course of a month started off slowly, with a hint of smoke in the air and what to many felt like seasonal allergies; watery eyes and an itching throat: normal symptoms that come in spring and quickly fade. However, what occurred over the next few days, from the apocalyptic sunsets to the emergency room visits for many asthmatics, shocked even the most jaded New Yorkers. Extreme weather events are becoming more frequent around the world, from devastating wildfires in Hawaii to recent flooding in Southern China. As the smoke from the wildfires clears and the waters recede, the fleeting attention of the world may move on, but the reality of climate change remains, increasingly difficult to ignore.

Since the release of the first Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report in 1990 (Houghton et al., Citation1990; Maslin et al., Citation2023; UN Climate Change, Citationn.d.), an impressive volume of scientific inquiry across the spectrum of environmental and human ecosystems has provided much needed and strong evidence, action, and policy recommendations for sustainable solutions to control the anthropogenic GHGs. It has led to the landmark agreements of Kyoto Protocol in 1997 (on stratospheric ozone hole) (United Nations, Citation1997), a model agreement (successfully implemented by signatory parties) and the Paris Agreement in 2015 (GHGs with limited compliance by signatory parties) (United Nations, Citation2015). However, according to the United Nations (UN), the world is not on track to meet the Paris climate goal of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels (United Nations, Citationn.d.). Like so many of the world’s problems, climate change will have sweeping implications for developing countries that are already struggling. Over the course of a 10-year period, between 2010 and 2020, the most vulnerable regions on the planet, home to upwards of 3.6 billion people, experienced mortality rates 15 times higher than low vulnerability countries due to climate change (World Health Organization, Citation2023). But as New Yorkers found out last summer, climate change is not a localized event: it will touch the lives of everyone. The global climate is intricately interconnected and events in one part of the globe can have cascading effects elsewhere from food shortages to climate refugees. There are no geographical borders with global events, and we can no longer dismiss what has been readily apparent for decades. After witnessing the haze over New York, it becomes clear that no place, regardless of its wealth or location, is immune from the effects of climate crises occurring worldwide. We are walking toward a slow-motion catastrophe, and it is imperative that we act with a unified voice so that we depart from the status quo.

The Relationships Between Human Activity, Climate Change, and the Resulting Effects Form a Complex System

A system is a group of different components that are not independent from each other but rather are interconnected (Cox et al., Citation2021; Lee et al., Citation2023; Lee, Bartsch, et al., Citation2017; Lee, Ferguson, et al., Citation2017; Mabry et al., Citation2022). These components interact with and affect one another in different ways. Since no part of a system is completely independent, what affects one part of a system could potentially affect many other things in the same system, influencing each other in a number of ways (both obvious and not). Thus, there are rarely single cause, single effect relationships, and a change in one part can reverberate throughout other parts of the system. Therefore, unless the system is well understood, it can be challenging to identify the root cause of an observed phenomenon or to predict the effects of a change or an intervention (Cox et al., Citation2021; Lee et al., Citation2023; Lee, Bartsch, et al., Citation2017; Lee, Ferguson, et al., Citation2017; Mabry et al., Citation2022). Additionally, systems and effects can cross different scales (Cox et al., Citation2021; Lee et al., Citation2023; Lee, Bartsch, et al., Citation2017; Lee, Ferguson, et al., Citation2017; Mabry et al., Citation2022). A scale is the size and scope of something (e.g., something occurring on the biological scale is smaller in size and scope than something that occurs at an individual behavioral scale). These different scales can interact with each other in various complex ways (Huang et al., Citation2011). The variability between scales can be challenging to fully appreciate since traditional academic disciplines and industry sectors oftentimes focus on particular scales. Complex systems involve complex mechanisms and interactions among multiple independent variables (e.g., biological, behavioral, social, economic) that play out over time to affect health.

Human activity, climate change, and the resulting impacts on the environment and humans comprise a complex system that is composed of many different subsystems, components/factors, and complex mechanisms that interact with one another in direct and indirect ways across different scales and timeframes. Global climate itself is a complex system composed of the atmosphere, ocean, soil, and many other subsystems that physically, chemically, and biologically interact with each other. Moreover, no singular human action is solely responsible for climate change, rather multiple, different individual human actions collectively over time contribute to climate change. For example, driving gas-powered cars, producing and disposing of plastics, and large-scale livestock farming are vastly different human actions that contribute differently to global GHG emissions that subsequently result in changes to the earth’s climate. Further, the impacts of climate change are varied, nonlinear, and occur over time oftentimes with delay between cause and effect, and cross multiple scales, affecting the environment, human health, and society. For example, climate change can induce a severe hurricane which can then result in human injury, infrastructure damage, natural habitat loss, and contamination of drinking water.

This interconnecting system can be seen through the lens of rainforest deforestation of the Amazon rainforest, which is at a tipping point. Over the past 50 years approximately 20% of the total land area of the Amazon has been destroyed for the world’s insatiable demand for beef and soy (Roy, Citation2022). To expand agricultural and livestock land, trees are cut down and burned, which removes a major sink for carbon dioxide and generates GHG through burning. The trees are often replaced with livestock which generate methane among other GHG and further the need for additional agricultural land for livestock feed. Modern agriculture uses a substantial amount of energy through the production of fertilizers and pesticides as well as heavy machinery to till the land, which degrades the soil and removes another critical carbon sink. The continuous need for land creates a self-perpetuating cycle which accelerates climate change and illustrates the profound and multifaceted impact of human activities on a complex system (Roy, Citation2022).

Misinformation and Disinformation About Climate Change Abound and Have Been Complex

Public perceptions toward climate change have been eroded due to persistent misinformation (i.e., misunderstandings or misrepresentations of climate science) and disinformation (i.e., deliberate creation and distribution of false information) predominantly in developed countries. Misinformation spread can happen with the best intentions (e.g., the sharer may not know the information is incorrect) (Torok et al., Citation2021). When a trusted person promotes misinformation, they attach their social capital to the information they share. Sometimes, when others try to provide corrected information, they are not believed because they do not have the same trusted relationship. At the same time, the trusted person may lose the trust of the people who previously listened to them if they correct their mistake. As a result, three aspects of the communication system are compromised – information, information sources, and information users. Too often, misinformation goes unnoticed until it has been widely disseminated and accepted as “fact.” In contrast, the intent of someone who shares disinformation is corrupt from the start. People can use false information to make a profit on harmful or unproven “treatments,” discredit scientists, reduce restrictions, reduce trust in government entities, influence public opinion, or distract from other things (e.g., job performance, support for other priorities). People may advance disinformation to promote hate and discrimination or to enact revenge for a perceived wrong. Such motivations can be hidden and difficult to uncover.

Mis/dis-information is not new. It has been used in the past for smoking tobacco, COVID-19, and vaccines (Ratzan, Citation2010). Driven by organizations, media, and individuals with vested interests, illusive, multiple, and diverse narratives are created and tailored to target audiences (Björnberg et al., Citation2017). These elaborate and well-funded networks single-handedly aim to confuse public opinion, and introduce skepticism and denial (Reed, Citation2016). They exploit climate’s complex and global scale, intergenerational timeline, multitude/diversity of drivers and outcomes, scientific inquiry rigor and robustness, and in challenging socioeconomic periods, impose false but relevant to audiences’ dilemmas (e.g., climate vs. jobs). They build on misunderstanding (e.g., global warming vs. cold spells), lack of perspective (e.g., altered precipitation/snowfall in Canada and freshwater availability in US rivers and lakes), and falsification (e.g., natural causes of climate change (Cook et al., Citation2018). Further, they have evolved over time, from “it is about polar bears,” to “climate change is not real,” to “not caused by carbon dioxide or humans,” to stay relevant, as scientific and real-life evidence debunked them.

The rapid expansion of the communication landscape with cable TV, talk radio, internet and social media is playing a catalytic role (Qiu et al., Citation2017). They afforded more options for the public to engage, but also led to selective exposure and biased point of views aligning with political party affiliations, rather than facts-based reporting. The internet accelerated accessibility and dissemination of information anonymously, without accountability, and created safe spaces to cultivate polarization, extremism, and violence. The explosive growth of social media had a multiplicative effect on the role of cable TV and internet on misinformation by affording the opportunity for individuals not to just receive but also use their cellphone to produce, respond to, and spread unfiltered snapshots of reality from their own perspective in a nick of time. And more recently, artificial intelligence holds the potential to accelerate disinformation by creating virtual realities (van der Ven et al., Citation2024). It is generally understood that content moderation may pose significant legal and technological challenges.

There’s Been a Lack of Urgent Response to Climate Change

Mis/dis-information campaigns to diffuse the responsibility of polluters, limit support for necessary public policies and delay practices to mitigate climate change have gained momentum in the past decade. This came with a cost, monetary, societal, and life. Climate has been changing for the past 50 years at a slow pace from a human’s perspective, asymmetrical and in many cases at an uncharted pace in unique ways by location. It is not just a distant threat to the environment (forests, glaciers, desert) or distant places (Africa, and islands), as portrayed in the past. Today, it is a major driver of societal unrest, conflict, and forced migration in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) around the world (Morales-Muñoz et al., Citation2020). It accounts for identifiable, measurable, and attributable direct and indirect consequences to the human ecosystem including declining quality of life, increasing cost of living, disease, and death in developed countries including the US and Western Europe (Lee, Citation2019, Citation2023a, Citation2023d; Rocque et al., Citation2021).

As climate, mis/dis-information evolves, so does the public and society. Gen X and Millennials have an elevated perception of threats and how climate will affect them throughout their lifetime rather than climate cognition and skepticism (Hickman et al., Citation2021). Baby Boomers are also catching up as, as frequent and intense climate-driven temperature extremes, wildfires, and extreme weather are the new norm, and they can now temporally align with climate change and compare with the past. Recognition that the climate is changing and that the change has been driven by GHG emissions is getting better. The debate and action now is shifting to solutions. As a result, the narrative of mis/dis-information is changing from “climate-denial” to “solution denial” to erode younger generations’ priorities for response to climate change as they grow like older age groups in the past (Barker & Bearce, Citation2013). However, the current state of climate threats to humans, resultant psychological responses, and the multiplicative effect of the internet and social media pose significant challenges to mis-/disinformation narratives. Moreover, scientific knowledge, cognitive, and communication frameworks are available to enhance awareness, recognition, and appreciation and diminish the influence of mis-/disinformation. And of course, the unwavering familiarity of Gen-X and Millennials with technology and social media.

Providing correct information on climate change is key to preparing target population groups and individuals to recognize, disregard, and even argue against misinformation (Cook et al., Citation2017). Contextually, it resembles the concept of vaccines but unlike them, it is a continuous effort and most of the time oblivious to the content and type of misinformation. The use of individual, local, and culturally relevant context is shown to enhance the adoption of the information, particularly when it is structured to support, rather than oppose personal morals and beliefs. Engaging with trusted facilitators holds the potential to improve accessibility and enhances the credibility of the message. Unlike previous misinformation experiences, climate change, although a global crisis, is a personal experience and that may be the instrument to combat climate misinformation that uses generalized statements (Benegal & Scruggs, Citation2018).

There Hasn’t Been Enough Focus on Communication in the Climate Change Arena Compared to Other Fields and Sectors

The spread of mis/dis-information about climate change and the lack of urgent responses suggest that current climate change communication efforts have not been effective. The lack of effectiveness is further highlighted by the current criticisms of climate change communication. For example, one main criticism is that the terms used are too complex (Fenton, Citation2022; Lee, Citation2023c; Moser, Citation2010; Torok et al., Citation2021). The general public does not readily understand climate-related terms such as “net zero,” “carbon emissions,” and “existential threat” (Fenton, Citation2022). However, climate scientists tend to use these terms and rely on the facts themselves (e.g., thinking that the logic and statistics/numbers are enough to be understood by the general public) (Fenton, Citation2022). Another criticism is that climate change communications lack personability, that they do not acknowledge or address the emotions, values, and culture of the intended audience (Doyle, Citation2022; Linsell, Citation2024). Both of these criticisms are in contrast to other sectors (e.g., business, marketing) that employ repeated delivery of simple, personable, and emotional messages that have proven to be effective in changing opinion or behavior (Linsell, Citation2024). Additionally, climate communication focuses heavily on the environment and does not typically account for the wider effects on human health and how policy actions can mitigate these effects on health (Depoux et al., Citation2017). Another criticism is that there is a lack of investment into climate communication (e.g., funds are not generally spent to ensure climate change messages reach the target audience) (Fenton, Citation2022). Further, there has not been a large-scale communication campaign, engagement with individuals and political leaders, and prioritization of public education efforts (Creutzig & Kapmeier, Citation2020; Li & Su, Citation2018).

Many other fields and sectors recognize the importance of communication. Marketing and advertising are a core component in the entertainment industry where these services are responsible for targeting specific viewing groups to generate interest and awareness in a particular film, television series, or event, which ultimately drives revenue and the product’s success. For example, studios typically engage audiences heavily before a movie is released, and spend a substantial amount on marketing and advertising, ranging from new articles/press to interviews with actors to movie posters to pre-screening events. Product manufacturers, like Apple, invest in consumer engagement before products reach the market (e.g., have launch events, preorders) and spend a lot on advertisements (e.g., TV, digital media, social media). As another example, the retail industry topped the list of spending for advertising in 2023, spending $2.56 billion (Nielson, Citation2024). Retailers use a wide variety of communication methods to promote products, including special events like concerts and product demonstrations, in store displays and pop ups, social media influencers, rewards programs, social and other online ads, newsletters, referral programs, direct mail, loyalty programs, e-mail marketing, search engine optimization, and others (Keenan, Citation2022). By comparison, there’s been a dearth of investment in climate change communication and less research into how such communication can be improved.

Communication Systems Themselves Are Complex

While climate change is a complex systems issue, so is communication itself. Communication crosses multiple systems that, in turn, can cross multiple scales. Therefore, to communicate most effectively, one must appreciate and understand these different systems. These systems include the information users (i.e., people) that are supposed to receive the communication and information, the communications channels, and the information itself. Conceptualizing communications as a complex system requires that we account both for the transactional nature of communication (i.e., how information is transferred from a sender to a receiver) and its constitutive nature (i.e., that communication is the process through which we co-create meaning and (re)establish individual, social, and cultural norms). If we think only of communication as the messages sent, we miss the opportunity to understand how communication involves a dynamic system that produces structures, processes, and outcomes that enables or disables our ability to characterize problems and generate solutions (McGreavy et al., Citation2015). Thus, conceptualizing communication as complex systems is critical to our understanding of climate change communication challenges and opportunities.

At the same time, different populations and communities are comprised of complex systems. Populations and communities are not homogenous blocks, but instead, are quite diverse and extremely heterogeneous (Lee et al., Citation2023). This diversity and heterogeneity extends beyond simplified demographic categories (e.g., race, ethnicity, immigration status, socioeconomic status, geospatial location) and it cannot be assumed that all those in a particular group are the same or conform to some common set of characteristics or stereotypes. Within different subpopulations and groups (e.g., demographic subcategory), there is a tremendous range of personalities, personal histories, interaction styles, and other characteristics that affect the ways people in these groups receive, process, and exchange information (Lee et al., Citation2023). For example, different people can get information from different sources and platforms (which may depend on factors such as close contacts, line of work, age, education) and may prioritize or favor different platforms or sources. Moreover, people within and across different communities interact, accept information, and share information with each other in very different and complex ways.

Additionally, populations and communities become more complex as they continue to grow and become more diverse. Communication strategies need to be tailored to resonate with the growingly complex array of information users. There is substantial research on different audience preferences, belief and value systems, and levels of trust that can help inform such strategies. This research should be leveraged when designing communications to ensure they are aligned, precise, and clear to different groups of users.

Communications channels (i.e., the ways by which people get their information) are also systems that are growing in their complexity and abundance as newer technologies emerge. Communications channels include a wide array of traditional channels including direct communications (e.g., press releases, speeches, print media like newspapers), radio and television (e.g., news), advertising (e.g., billboards, television commercials), entertainment (e.g., product placement within movies and live shows), workplace-based communications (e.g., statements by organizational leaders, newsletters), school-based communications (e.g., announcements, lectures, flyers, posters), community-based communications (e.g., clubs, religious/other social gatherings, concerts, sporting events), as well as direct person-to-person interactions, which could take place in a variety of settings (e.g., workplaces, family and friends, neighborhoods). These traditional channels have grown in complexity (e.g., advertising has become more pervasive, especially with the advent of digital marketing tools). Additionally, newer communication channels have emerged, including e-mail, direct messaging apps (e.g., WhatsApp, Slack, Skype), podcasts, websites, internet search engines (e.g., Google, DuckDuckGo), internet discussion boards (e.g., Reddit, Quora), social media (e.g., X, Facebook, TikTok), and news aggregators (e.g., Apple News, Google News). Both traditional and newer communication channels work via different mechanisms, which collectively make the flow of information non-linear and complex.

There Is a Need for More Systems Approaches to Climate Change Communication

A systems approach is about considering the entire relevant system when making any important evaluation, decision, or plan rather than focusing on just one part or aspect of the system (Cox et al., Citation2021; Lee et al., Citation2023; Lee, Bartsch, et al., Citation2017; Lee, Ferguson, et al., Citation2017; Mabry et al., Citation2022). With many people sitting in disciplines, specialties, sectors, industries, and roles that are very narrow, siloed, and don’t regularly communicate and interact with each other, there can be a tendency to not take a systems approach and, in turn, stay narrowly focused. Moreover, the focus can be on short-term, immediate, and readily noticeable effects and goals rather than longer term ones when not taking a systems approach. When a systems approach is not used, the result can be band-aids rather than sustainable solutions, missing secondary, tertiary, and other indirect effects (thus underestimating the problem), creating unintended consequences, collecting superfluous and misleading information (unguided data collection), developing solutions that are not sustainable over time, necessitating trial-and-error to develop and test interventions, and implementing solutions that potentially exacerbate issues/disparities if solutions can only work for some people.

Taking more of a systems approach also means making use of different systems methodologies to facilitate communication. One such methodology is systems mapping. A systems map or diagram is a visual representation of all the components of the system of interest and their relationships with each other (e.g., how they may interact with and affect each other). Systems maps typically make use of different mapping conventions to represent the different components with shapes and show relationships with lines and arrows. Such maps can show how different people’s conceptualizations of a system may be similar versus different, which helps to then identify a more comprehensive representation of the system (Cox et al., Citation2021; Lee, Bartsch, et al., Citation2017; Lee, Ferguson, et al., Citation2017). One way to develop systems maps is through mapping workshops, which involves convening diverse representatives with expertise in the system of interest (e.g., climate change and communication experts), including a wide range of disciplines and sectors (e.g., research, government, journalism, media). During a mapping workshop, facilitators typically guide participants to identify factors and mechanisms that contribute to the system of interest. For example, facilitators may begin by posing clear, open-ended questions that guide the participants to brainstorm different components that are relevant to the map. After this, facilitators may lead an open discussion that helps to further build out the map. Follow up sessions with experts may help further refine and augment the systems map. This special issue includes an example of such a systems map that elucidates the challenges of communicating about climate change and its impacts, and proposes potential solutions.

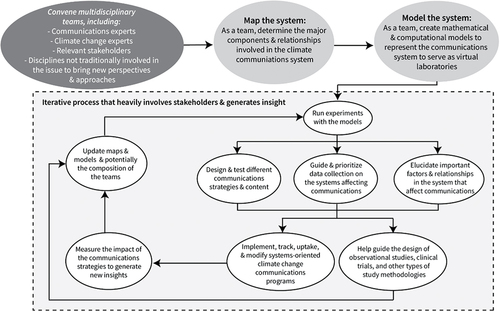

Another methodology is systems modeling which represents the factors, processes, mechanisms, and effects within the system using mathematical equations and executes these equations using computers (Mabry et al., Citation2022). Systems maps can be used as a blueprint for a systems model. A systems map becomes a systems model when one adds quantitative representations (e.g., mathematical equations) of the relationships and processes that link different components in the system (Mabry et al., Citation2022). These equations can represent a situation at a particular point in time (i.e., a static model) or simulate what happens over time (i.e., a dynamic simulation model). Systems models are then populated, calibrated, and validated using data. The equations in a systems model can use specific values for a deterministic model or incorporate variability and uncertainty in data values, thereby making it stochastic. A systems model can serve as a virtual laboratory to test different possibilities and such virtual experimentation has advantages over real-world trial-and-error, which can end up wasting considerable time, effort, and resources or even be ethically or logistically unfeasible. In fact, as seen in , systems models can even help guide the design of observational studies, clinical trials, and other types of study methodologies. Systems models have been increasingly used to make decisions in fields such as meteorology, manufacturing, pandemic preparedness and response, healthcare operations, and obesity prevention and control (Bartsch et al., Citation2021, Citation2024; Cox et al., Citation2021; Huang et al., Citation2011; Lee et al., Citation2021; Lee, Bartsch, et al., Citation2017; Lee, Ferguson, et al., Citation2017; Lee, Mueller, et al., Citation2017; Martinez et al., Citation2024; Powell-Wiley et al., Citation2017, Citation2024).

As shows, systems mapping and modeling should proceed in an iterative manner (Cox et al., Citation2021; Lee et al., Citation2023; Lee, Bartsch, et al., Citation2017; Lee, Mueller, et al., Citation2017; Mabry et al., Citation2022). The first iteration of a systems map and model can be a rough approximation. Such a rough conceptualization of the system can then help identify the current knowledge and data gaps and in turn guide the design of subsequent studies and data collection. Insights and data from these subsequent studies and data collection activities can help update and further refine the systems map and model. One can then continue this iterative process, making the map, model, studies, data collection activities, and insights more accurate and precise with each cycle. Over time, this iterative process can move toward an increasingly better understanding of the entire system.

How Systems Approaches Can Lead to More Proactive Precision Communication About Climate Change

By better elucidating the complexities involved with the information, communication channels, and potential audiences, systems approaches and methods can lead to more precision communication about climate change. Precision communication is when communication is appropriately tailored for differences and diversity that exist in the type of information communicated, the communication channels used, and the intended audiences. It does not treat communication as one-size-fits-all and instead accounts for the complexity and heterogeneity that exists within and across the system involved. shows what precision communication entails and how to do this at each step/part of the communication system. There is the saying that if you tell 10 different people the exact same thing, you may get 10 different interpretations. Precision communications involves really understanding and anticipating how information may be distributed and received before communication has even occurred and then adjusting the delivery and packaging of this information accordingly. In this way, precision communication is a more proactive approach to communication.

The past decade has seen a paradigm shift from a one-size-fits-all approach to precision efforts, such as precision medicine, precision nutrition, and precision population health (Lee, Citation2022a, Citation2022b, Citation2023e; Lee et al., Citation2022). These efforts have aimed to develop treatments, diets, and other approaches that better account for the differences among people and their circumstances. They aim to eschew traditional approaches that do not account for the complexity of the systems involved. These precision efforts are made possible with a better understanding of the causal pathways and complexity involved in the relevant systems and are about finding the real determinants and root causes to provide effective solutions. Thus, systems approaches and methods are important in this paradigm as they consider the entire system, including its constellation of factors and how they interact. The time has come for precision communication for climate change where such systems approaches help to identify and develop more effective, tailored, and precise communication for climate change.

Society Is at an Inflection Point

As shows, now more than ever, our society is at an inflection point (Schäfer & Hase, Citation2023). The records for greenhouse gas levels, surface temperatures, ocean heat and acidification, sea level rise, Antarctic sea ice cover, and glacier retreat were all broken in 2023, and we experienced the effects from climate change globally, including heatwaves, floods, droughts, wildfires, and tropical cyclones (Lee, Citation2023b; World Meteorological Organization, Citation2024). These effects and others have led to negative impacts to human health and billions in economic losses over time (World Meteorological Organization, Citation2024). Moreover, the State of Climate Action 2023 found that global efforts to limit warming of 1.5 degrees Celsius are failing across the board, with progress on almost every indicator substantially behind that which is necessary to address the climate crisis (Boehm et al., Citation2023). These and other indicators highlight that current approaches to climate communication have not been effective and are in need of new, innovative ideas, approaches, and tools.

Table 1. How society is at an inflection point

At the same time, there is substantially more climate change data from different, disparate, and wide-ranging sources and a wider availability of analytic tools with greater computational resources and power compared to previous years. Such sources and tools include the FAO GeoNetwork, NASA Earth Observatory, and UNEP Environmental Data Explorer (GISGeography, Citation2023). Systems approaches can serve as vital tools by integrating these data sources to allow us to make better use of the insights these data can provide when they are used to elucidate the complexities of the wider system. With greater understanding of the capabilities of systems approaches and investment of resources and focus into climate communication, it is our hope these methods lead to more effective communication strategies that consider the wider systems they are a part of. Moreover, with a greater recognition of the existing strengths/limitations of current climate change communication strategies, systems approaches can help decision makers prioritize initiatives, save time, effort, and money, and better allocate limited resources among different climate communication research efforts. Further, most systems are dynamic and tend to change and evolve over time. For example, people may become increasingly environmentally conscious as climate change worsens, and as a result may become more willing to adopt behaviors to mitigate the effects. Therefore, as climate continues to change and people’s attitudes toward climate change and its effects transform, communication strategies must also adapt to account for these changes over time.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barker, D. C., & Bearce, D. H. (2013). End-times theology, the shadow of the future, and public resistance to addressing global climate change. Political Research Quarterly, 66(2), 267–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912912442243

- Bartsch, S. M., O’Shea, K. J., John, D. C., Strych, U., Bottazzi, M. E., Martinez, M. F., Circiriello, A., Chin, K. L., Weatherwax, C., Velmurugan, K., Heneghan, J. L., Scannell, S. A., Hotez, P. J., & Lee, B. Y. (2024). The potential epidemiologic, clinical, and economic value of a universal coronavirus vaccine: A modelling study. EClinicalMedicine, 68, 102369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102369

- Bartsch, S. M., Wong, K. F., Mueller, L. E., Gussin, G. M., McKinnell, J. A., Tjoa, T., Wedlock, P. T., He, J., Chang, J., Gohil, S. K., Miller, L. G., Huang, S. S., & Lee, B. Y. (2021). Modeling interventions to reduce the spread of multidrug-resistant organisms between health care facilities in a region. JAMA Network Open, 4(8), e2119212. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.19212

- Benegal, S. D., & Scruggs, L. A. (2018). Correcting misinformation about climate change: The impact of partisanship in an experimental setting. Climatic Change, 148(1), 61–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2192-4

- Björnberg, K. E., Karlsson, M., Gilek, M., & Hansson, S. O. (2017). Climate and environmental science denial: A review of the scientific literature published in 1990–2015. Journal of Cleaner Production, 167, 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.08.066

- Boehm, S., Jeffery, L., Hecke, J., Schumer, C., Jaeger, J., Fyson, C., Levin, K., Nilsson, A., Naimoli, S., Daly, E., Thwaites, J., Lebling, K., Waite, R., Collis, J., Sims, M., Singh, N., Grier, E., Lamb, W., Castellanos, S. & Masterson, M. (2023). State of climate action 2023. World Resources Institute. https://doi.org/10.46830/wrirpt.23.00010

- Cook, J., Ellerton, P., & Kinkead, D. (2018). Deconstructing climate misinformation to identify reasoning errors. Environmental Research Letters, 13(2), 024018. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aaa49f

- Cook, J., Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., & Manalo, E. (2017). Neutralizing misinformation through inoculation: Exposing misleading argumentation techniques reduces their influence. PLOS One, 12(5), e0175799. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175799

- Cox, S. N., Wedlock, P. T., Pallas, S. W., Mitgang, E. A., Yemeke, T. T., Bartsch, S. M., Abimbola, T., Sigemund, S. S., Wallace, A., Ozawa, S., & Lee, B. Y. (2021). A systems map of the economic considerations for vaccination: Application to hard-to-reach populations. Vaccine, 39(46), 6796–6804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.033

- Creutzig, F., & Kapmeier, F. (2020). Engage, don’t preach: Active learning triggers climate action. Energy Research and Social Science, 70, 101779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101779

- Depoux, A., Hémono, M., Puig-Malet, S., Pédron, R., & Flahault, A. (2017). Communicating climate change and health in the media. Public Health Reviews, 38(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-016-0044-1

- Doyle, J. (2022). Communicating climate change in ‘don’t look up’. Journal of Science Communication, 21(5), 1. https://doi.org/10.22323/2.21050302

- Fenton, D. (2022). Climate change: A communications failure. The Hill. https://thehill.com/opinion/energy-environment/3709795-climate-change-a-communications-failure/

- GISGeography. (2023). 7 free world climate data sources. https://gisgeography.com/free-world-climate-data-sources/

- Hickman, C., Marks, E., Pihkala, P., Clayton, S., Lewandowski, R. E., Mayall, E. E., Wray, B., Mellor, C., & van Susteren, L. (2021). Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. The Lancet Planet Health, 5(12), e863–e873. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3

- Houghton, J. T., Jenkins, G. J., & Ephraums, J. J. (1990). Climate change : The IPCC scientific assessment. Cambridge University Press.

- Huang, T. T. K., Grimm, B., & Hammond, R. A. (2011). A systems-based typological framework for understanding the sustainability, scalability, and reach of childhood obesity interventions. Children’s Health Care, 40(3), 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/02739615.2011.590399

- Keenan, M. (2022). What is retail marketing? 9 strategies & examples (2024). shopify. https://www.shopify.com/retail/retail-marketing#11

- Lee, B. Y. (2019). Study shows how pollution, climate change could make us dumber. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucelee/2019/12/22/study-shows-how-pollution-climate-change-could-make-us-dumber

- Lee, B. Y. (2022a). Could precision nutrition be a game changer for health?. Medpage today. https://www.medpagetoday.com/popmedicine/popmedicine/98305

- Lee, B. Y. (2022b). What is precision nutrition? How it can transform your diet and health. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucelee/2022/08/15/what-is-precision-nutrition-how-it-can-transform-your-diet-and-health/

- Lee, B. Y. (2023a). Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever, CCHF, virus spreading in Europe due to climate change. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucelee/2023/07/08/crimean-congo-hemorrhagic-fever-cchf-virus-spreading-in-europe-due-to-climate-change/

- Lee, B. Y. (2023b). July 4 was the hottest day ever recorded worldwide. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucelee/2023/07/05/july-3-was-the-hottest-day-ever-recorded-worldwide/

- Lee, B. Y. (2023c). Meteorologist Names 2023 U.S. Heat waves after oil, gas companies: Amoco, BP, Chevron. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucelee/2023/07/29/meteorologist-names-2023-us-heat-waves-after-oil-gas-companies-amoco-bp-chevron/

- Lee, B. Y. (2023d). Study: How much airplane turbulence has increased with climate change since 1979. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucelee/2023/07/06/study-how-much-airplane-turbulence-has-increased-with-climate-change-since-1979

- Lee, B. Y. (2023e). What is precision population health? Here’s why it’s needed. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucelee/2023/05/12/what-is-precision-population-health-why-is-it-needed/

- Lee, B. Y., Bartsch, S. M., Mui, Y., Haidari, L. A., Spiker, M. L., & Gittelsohn, J. (2017). A systems approach to obesity. Nutrition Reviews, 75(suppl 1), 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuw049

- Lee, B. Y., Ferguson, M. C., Cox, S. N., & Phan, P. H. (2021). Big data and systems methods: The next frontier to tackling the global obesity epidemic. Obesity (Silver Spring), 29(2), 263–264. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23062

- Lee, B. Y., Ferguson, M. C., Hertenstein, D. L., Adam, A., Zenkov, E., Wang, P. I., Wong, M. S., Gittelsohn, J., Mui, Y., & Brown, S. T. (2017). Simulating the impact of sugar-sweetened beverage warning labels in three cities. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 54(2), 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.11.003

- Lee, B. Y., Greene, D., Scannell, S. A., McLaughlin, C., Martinez, M. F., Heneghan, J. L., Chin, K. L., Zheng, X., Li, R., Lindenfeld, L., & Bartsch, S. M. (2023). The need for systems approaches for precision communications in public health. Journal of Health Communication, 28(sup1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2023.2220668

- Lee, B. Y., Mueller, L. E., & Tilchin, C. G. (2017). A systems approach to vaccine decision making. Vaccine: X, 35(Suppl 1), A36–A42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.033

- Lee, B. Y., Ordovas, J. M., Parks, E. J., Anderson, C. A. M., Barabasi, A. L., Clinton, S. K., de la Haye, K., Duffy, V. B., Franks, P. W., Ginexi, E. M., Hammond, K. J., Hanlon, E. C., Hittle, M., Ho, E., Horn, A. L., Isaacson, R. S., Mabry, P. L., Malone, S., Martin, C. K. & Martinez, M. F. (2022). Research gaps and opportunities in precision nutrition: An NIH workshop report. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 116(6), 1877–1900. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqac237

- Linsell, T. (2024). Failure to communicate clearly to the public is hurting climate-change action. Policy Options. https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/january-2024/poor-communication-climate-policy/

- Li, N., & Su, L. Y.-F. (2018). Message framing and climate change communication: A meta-analytical review. Journal of Applied Communications, 102(3), 1. https://doi.org/10.4148/1051-0834.2189

- Mabry, P. L., Pronk, N. P., Amos, C. I., Witte, J. S., Wedlock, P. T., Bartsch, S. M., & Lee, B. Y. (2022). Cancer systems epidemiology: Overcoming misconceptions and integrating systems approaches into cancer research. PLOS Medicine, 19(6), e1004027. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004027

- Martinez, M. F., Weatherwax, C., Piercy, K., Whitley, M. A., Bartsch, S. M., Heneghan, J., Fox, M., Bowers, M. T., Chin, K. L., Velmurugan, K., Dibbs, A., Smith, A. L., Pfeiffer, K. A., Farrey, T., Tsintsifas, A., Scannell, S. A., & Lee, B. Y. (2024). Benefits of meeting the healthy people 2030 youth sports participation target. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 66(5), 760–769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2023.12.018

- Maslin, M. A., Lang, J., & Harvey, F. (2023). A short history of the successes and failures of the international climate change negotiations. UCL Open Environment, 5, e059. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.444/ucloe.000059

- McGreavy, B., Lindenfeld, L., Bieluch, K. H., Silka, L., Leahy, J., & Zoellick, B. (2015). Communication and sustainability science teams as complex systems. Ecology and Society, 20(1). http://www.jstor.org/stable/26269712

- Morales-Muñoz, H., Jha, S., Bonatti, M., Alff, H., Kurtenbach, S., & Sieber, S. (2020). Exploring connections—environmental change, food security and violence as drivers of migration—a critical review of research. Sustainability, 12(14), 5702. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145702

- Moser, S. C. (2010). Communicating climate change: History, challenges, process and future directions. WIREs Climate Change, 1(1), 31–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.11

- Nielson. (2024). Top 20 categories by ad spend for 2023 revealed in latest Nielsen Ad Intel report. https://www.nielsen.com/news-center/2024/top-20-categories-by-ad-spend-for-2023-revealed-in-latest-nielsen-ad-intel-report/

- Powell-Wiley, T. M., Martinez, M. F., Heneghan, J., Weatherwax, C., Osei Baah, F., Velmurugan, K., Chin, K. L., Ayers, C., Cintron, M. A., Ortiz-Whittingham, L. R., Sandler, D., Sharda, S., Whitley, M., Bartsch, S. M., O’Shea, K. J., Tsintsifas, A., Dibbs, A., Scannell, S. A., & Lee, B. Y. (2024). Health and economic value of eliminating socioeconomic disparities in US youth physical activity. JAMA Health Forum, 5(3), e240088. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2024.0088

- Powell-Wiley, T. M., Wong, M. S., Adu-Brimpong, J., Brown, S. T., Hertenstein, D. L., Zenkov, E., Ferguson, M. C., Thomas, S., Sampson, D., Ahuja, C., Rivers, J., & Lee, B. Y. (2017). Simulating the impact of crime on African American Women’s physical activity and obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring), 25(12), 2149–2155. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22040

- Qiu, X., Oliveira, D. F. M., Sahami Shirazi, A., Flammini, A., & Menczer, F. (2017). Limited individual attention and online virality of low-quality information. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(7), 0132. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0132

- Ratzan, S. C. (2010). Setting the record straight: Vaccines, autism, and the lancet. Journal of Health Communication, 15(3), 237–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810731003780714

- Reed, M. (2016). ‘This loopy idea’ an analysis of UKIP’s social media discourse in relation to rurality and climate change. Space and Polity, 20(2), 226–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2016.1192332

- Rocque, R. J., Beaudoin, C., Ndjaboue, R., Cameron, L., Poirier-Bergeron, L., Poulin-Rheault, R. A., Fallon, C., Tricco, A. C., & Witteman, H. O. (2021). Health effects of climate change: An overview of systematic reviews. British Medical Journal Open, 11(6), e046333. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046333

- Roy, D. (2022). Deforestation of Brazil’s Amazon has reached a record high. What’s being done?. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/deforestation-brazils-amazon-has-reached-record-high-whats-being-done

- Schäfer, M. S., & Hase, V. (2023). Computational methods for the analysis of climate change communication: Towards an integrative and reflexive approach. WIREs Climate Change, 14(2), e806. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.806

- Torok, S., Goldie, J., & Ashcroft, L. (2021). Communicating climate change has never been so important, and this IPCC report pulls no punches. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/communicating-climate-change-has-never-been-so-important-and-this-ipcc-report-pulls-no-punches-165252

- UN Climate Change. (n.d.). Background – Cooperation with the IPCC. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). https://unfccc.int/topics/science/workstreams/cooperation-with-the-ipcc/background-cooperation-with-the-ipcc

- United Nations. (1997). A Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXVII-7-a&chapter=27&clang=_en

- United Nations. (2015). D Paris Agreement. https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXVII-7-d&chapter=27&clang=_en

- United Nations. (n.d.). Climate action fast facts. https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/science/key-findings

- van der Ven, H., Corry, D., Elnur, R., Provost, V. J., & Syukron, M. (2024). Generative AI and social media may exacerbate the climate crisis. Global Environmental Politics, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00747

- World Health Organization. (2023). Climate change. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health

- World Meteorological Organization. (2024). State of the global climate 2023. https://library.wmo.int/idurl/4/68835