ABSTRACT

The aim of this study is to examine, to what extent the chance of survival of children under 5 years of age was influenced by a biological parent’s death in the region of western Bohemia. Young children’s mortality is considered in relation to family structure, since persons raising the child in its early childhood significantly influenced the quality of child care. Given the gender-specific division of labour in pre-modern families we focus chiefly on the possible different effects of a mother’s death or a father’s death. In addition, we try to establish whether the negative impact of a biological parent’s death could be compensated by the entrance of a stepparent. For the purposes of this analysis we used the Cox proportional hazards mixed-effect model. Our research has shown that although maternal death had more serious consequences compared to paternal death, especially if it occurred in the child’s first year of life, even paternal death increased child mortality since the need to assume the paternal role prevented the surviving mother from taking optimum care of her children. The entrance of a stepparent in general increased children’s chance of survival although in the case of stepmothers the positive effect was limited and could mainly be observed among children over 3. In contrast, our research has shown that there was no major difference in survival chances resulting from the presence of a biological father vs. a stepfather, an interesting result demonstrating that in the functioning of the pre-modern family biological ties were of only relative importance.

1. Introduction

Until the second half of the 19th century it was not unusual for parents in Europe to be faced with the loss of their young children. In a similar way, children often experienced the death of a parent at a time when they were still dependent on parental care. The death of a child could influence reproductive strategies (Tymicki, Citation2005), whereas the death of a parent could significantly reduce the child’s chance of survival. This effect has already been described in previous studies related to parental death (Beekink et al., Citation2002; Hill & Hurtado, Citation1996; Willführ & Gagnon, Citation2013).

These studies usually emphasize that a mother’s death was a more serious threat to the child’s survival than a father’s death, especially if it occurred in the first months of a child’s life, given that maternal care is considered as a major determinant of infant and child survival (Pavard et al., Citation2005; Sear & Mace, Citation2008). The child’s mother was usually its main carer whose death could directly threaten its life, especially if the mother’s death occurred within one year after birth when the child was still breastfed (Åckerman et al., Citation1996; Beekink et al., Citation1999; Dvořáčková-Malá et al., Citation2019, pp. 237–238). In contrast, the effects of the loss of a male breadwinner are said to be more diffuse. Rather than a direct increase in mortality, the loss of a father resulted in the impoverishment of the family, making the children leave home to do domestic service earlier than was usual or causing them other economic disadvantages such as receiving a lower inheritance share or a smaller dowry. (Beise, Citation2005; Derosas & Oris, Citation2002; Dribe, Citation2000; Hill & Hurtado., Citation1996; Slováková, Citation2018). The influence of parental death was thus long-lasting and may have persisted even in the child’s adulthood (Rosenbaum-Feldbrügge, Citation2020).

The effects of a mother’s vs. a father’s death differed also in the frequency of remarriage by the widowed parent. If a child lost its mother it was more likely to be brought up by a stepmother, given that when a mother died leaving behind small children, the surviving husband usually remarried (Moring & Wall, Citation2017, p. 194–209; Fauve-Chamoux, Citation2010, pp. 291–292; Kurosu, Citation2007; Lundh, Citation2007, pp. 378–380). In contrast to men, widowed women did not remarry so often. The most commonly cited factors influencing remarriage among women are age and property status. However, there were other important aspects which a widow considered before remarrying, such as whether she had already fulfilled her maternal role or whether she preferred to maintain her position as an independent farmer, acquired through widowhood. Quite obviously, what also mattered was the personality of a potential suitor (Lanzinger, Citation2018a; Skořepová & Grulich, Citation2017; Skořepová, Citation2016, p. 111; Brown, Citation2002, p. 118–119; Velková, Citation2010). In any case, we may suppose that the decision of the surviving partner whether to remarry or not played a major role in the lives of the orphaned children, including their chance of survival. It remains to be seen, however, whether the care provided by a stepparent always improved the child’s condition or whether quite the opposite could occur based on the so-called ‘Cinderella’ effect (Daly & Wilson, Citation1998; Lanzinger, Citation2018b; Perrier, Citation2006; Warner, Citation2018; Willführ & Gagnon, Citation2013). The studies conducted so far do not provide a sufficiently clear answer to this question. While analyses of Swedish and Chinese data from the 19th century confirmed that children with stepmothers had a similar risk of death as children who were raised by their own mothers, this risk being considerably lower than when the child had no mother at all (Åckerman et al., Citation1996; Campbell & Lee, Citation2002), research carried out in Quebec did not prove any such effect, since living with a stepmother did not affect child mortality in this population. A study in Krummhörn, Germany showed the opposite – that the co-residence with a stepmother had a negative influence on child mortality, especially on orphaned girls (Willführ & Gagnon, Citation2013). As for stepfathers, their role is usually assessed in terms of their economic contribution, which, like in the case of biological fathers, was seen as a factor supporting the mother’s reproduction. Unlike the role of stepmothers, however, the role of stepfathers in influencing mortality rates of stepchildren has not been studied nearly as often, and the research conducted until now has not provided a clear answer.

The aim of this study is to examine the extent to which the chance of survival of children under 5 years of age was influenced by their biological parent’s death in the region of western Bohemia. We will also try to find out whether the mortality rates of orphaned children changed when the surviving parent remarried and a new stepfamily was formed. We also realize that the phenomenon of stepfamily itself consists of a whole range of different aspects, which are impossible to discuss here (Warner, Citation2018) and also that stepparents were not the only persons who could replace parental childcare and consequently influence the chances of survival of an orphaned child. Our previous research showed the important beneficial effect of grandmothers‘ presence among landless families, i.e. mainly poor families where the mother often performed hired labour and wasn’t able to pay someone else to care for her small children (Havlíček et al., Citation2021; Horský & Velková, Citation2020; Velková & Fialová, Citation2020). However, the aim of this study was not to find out which person could most increase the child’s chances of survival in the event of a parent’s death or to study the impact of different types of co-resident kin (Kok et al., Citation2011). The main questions which we are trying to address in the present study are: What was the difference in mortality rate between children who lost their mother vs. those who lost their father? How were the chances of survival of the half-orphaned children influenced by the entrance of a stepparent into the family?

The answers to these questions can help us better understand to what extent mortality rates of young children were affected by the family structure in which they were raised and hence, by the care they were given. We will also focus on whether the age of becoming orphaned could determine the chance of survival and whether it is possible to establish an age limit after which family structure ceased to be a fundamental factor for the child’s survival.

2. Sources and methodology

The present analysis is based on research conducted on the domain of Šťáhlavy in western Bohemia near the city of Pilsen. Throughout the 18th and the beginning of the 19th centuries the Šťáhlavy estate continued to retain its predominantly rural character. While the population under study consisted chiefly of people farming the land, it also included some craftsmen and workers from a local iron mill. Social stratification of the population has changed in the said period. Similarly as in other European regions, the landless became the most numerous population stratum. While in the second half of the 17th century, full peasant holders and smallholders (holding less than five hectares of land) predominated in the population, accounting for ca 50%, around 1820 their share decreased to 25%, with a simultaneous rise of the cottager population (27%), which in general was constituted as a class only in the course of the 18th century, and with the landless as the most populous group, accounting for 29% (Velková, Citation2009, Citation2012). Despite the fact that the state began to enter more frequently into the relationship between the landlords and their subjects, the main changes were brought about by the process of urbanisation and industrialisation, which only began to influence the rural areas in the second quarter of the 19th century (Dokoupil et al., Citation1999).

The parental socioeconomic status was one of the factors included in our model which may explain possible confounds. We divided the families into three main social groups. The first category comprised full peasant holder (sedlák, Bauer) and smallholder (chalupník, Chalupner, Kleinbauer) families, who made their living by farming the land. The second category encompassed the remaining social groups within the settled population (ansässig), i. e. cottagers (domkář, Häusler), who unlike members of the previous category did not hold any land and usually earned their living as craftsmen or iron-mill workers. The third category included the remaining landless people (houseless lodgers, podruh, Inwohner, Hausgenosse), such as farm labourers, shepherds or unsettled craftsmen.

Given that we used the time-consuming method of family reconstruction, based on data from parish registers, we were unable to excerpt data from the entire estate, which in the mid-19th century comprised as many as fifty communities. This is why we narrowed our research to four localities belonging to one parish with its seat in Starý Plzenec: namely Starý Plzenec itself, the only small town of the estate, Šťáhlavy, the administrative centre of the domain, and two little villages of Sedlec and Lhůta, situated near the iron mills owned by the local landlord. We focused on children born in these four localities in the period 1708–1834. The start of this period was set in accordance with the year when the first death register was established, since without knowing the dates of death we could not carry out an analysis of mortality. The database, however, contains data on people who were born after 1651, when the first birth register was founded, since it was important to reconstruct also those relationships which existed in a given family before the children under analysis were born (especially data concerning their parents and grandparents).Footnote1 When it was necessary for the purposes of the family reconstruction to have other data such as the birth and death dates of the analysed children’s parents and grandparents, we also searched registers kept in other parishes. The upper limit, 1834, was selected so as to ensure that the persons born in the given period lived their childhood before the manorial system was abolished in the mid-19th century. In the early 18th century, the total population of the four localities was approximately one thousand people, increasing to around 2,500 people towards the end of the period under study. Our database contained 15,915 inhabitants of the domain of Šťáhlavy. Out of these, a total of 6,618 children who fulfilled the following criteria, were subject to our analysis. Firstly, they had to be born in one of the four communities in the period 1708–1834. Secondly, they had to be born as legitimate children; we did not include children of single mothers. A third important criterion which needed to be proved by the family reconstruction was that the child under analysis had to have at least one full sibling, who was also born in one of the four localities. We set out this condition in order to eliminate those families who settled in the four communities only temporarily, e.g., for several months only, since it would have been very demanding to collect other necessary data (such as dates of birth of the parents), as it was often impossible to find out from where a family came.

Fourthly, in order to be included in the database, the date of the child’s and parent’s death had to be known, or alternatively there had to be evidence proving that the child in question lived in one of the places until it reached age five. If the date of the child’s death was missing but we knew the date of its marriage or if there were conclusive records of the family (younger siblings being born, one of the parents dying etc.) we were confident that if the child died, its death did not go unnoticed in the death registers. Therefore, we treated it as alive until the age of 5 (after that all the children were essentially treated as ‘censored’ datapoints that survived until the threshold of interest). If we did not have conclusive records about the child’s family up to its five years of age we excluded the child from the analysis (in such cases the condition that we needed to have a record of the parent’s death proving that he/she died before the child was five was not usually fulfilled because the whole family moved away). Thus, we assumed that if our sources confirmed that a family did not move within the first five years of the child’s life and unless we found any data on its death, the child in question survived early childhood and later migrated and died somewhere else (Willführ & Gagnon, Citation2013, p. 196). We chose this approach because we realized that if we had limited our analysis only to those families for which we managed to compile all the relevant data, we would have significantly reduced the number of analysed families, and at the same time we would be distorting the overall picture since the results obtained would correspond more to the lifestyles of the settled rather than mobile families. This approach would automatically place more weight on children whose date of death we knew because they died before age 5 and would result in exceedingly high levels of child mortality not corresponding to reality. On the other hand, if we had automatically included all the children in the database, regardless of whether we knew their date of death, our data would be biased in the opposite sense, since there were undoubtedly families who did not stay in their child’s birthplace for the whole five years. In this case, a missing record of the date of death may have meant that the whole family moved and the child died before reaching age 5 outside the four places we selected for our analysis. We took a similar approach also when the data on the death of the biological parents were missing. Thus, we included in our database even those children for whom the exact dates of their parents’ biological death were unavailable but where, on the basis of family reconstruction, we were able to deduce that both the father and the mother lived at least until their child reached age 5.

As for the age limit of five years, we chose it for several reasons, chiefly because mortality rates were the highest precisely in the first five years of a child’s life. In the Czech lands, the situation in this respect did not change until the end of the 19th century: approximately 35–45% of the children died before reaching age five (with boys dying more often than girls). (Dokoupil et al., Citation1999, pp. 50–57; Nováková, Citation2003). The data available for the whole Czech lands show that in 1851–1854, per one thousand children, 426 boys and 373 girls died under age 5, most of them dying in the first year of their life: 271 boys and 227 girls (Fialová, Citation2000, p. 174). The situation on the domain of Šťáhlavy was similar (see the ). The high infant mortality influenced the life expectancy at birth, which was low: until the mid-nineteenth century, life expectancy in Bohemia was approximately 30, increasing to 40 by the end of the century (Srb & Molinová, Citation2003, pp. 191–192). Older children (5–14 years old) died much less often (their mortality rate was about 100) and their death was usually due to specific causes such as infectious diseases, injury or drowning, i.e. causes no longer directly related to the care received in th family. As for the younger children, we suppose that their mortality rate was indeed closely connected with specific family circumstances, especially with the household structure. The quality of care usually provided by parents may have been decisive for their survival. We can therefore assume that the loss of a parent at this vulnerable age could significantly influence the mortality of these very young children (Pavard et al., Citation2005).

Research has also shown, however, that losing a parent at such an early age did not occur too often. Even though due to low life expectancy, about one half of the marriages concluded in the 18th and in the first half of the 19th centuries lasted less than 15 years, the share of children orphaned before their fifth birthday was relatively modest. The probability of losing one’s parents naturally increased with the child’s age and therefore orphanhood was more frequent among older age groups (Kuprová, Citation2013, p. 47; Dušek, Citation1985, p. 201; Beekink et al., Citation2002). Namely, on the domain of Šťáhlavy, persons who died between the ages of 30 and 49 represented about 10% of all the deceased, and their proportion began to slowly decrease from the beginning of the 19th century. At the same time, the mortality conditions of the oldest persons began to improve, which resulted in an increase in the average age of death of those aged 50+ (Velková, Citation2009, pp. 437–438). As for the Šťáhlavy domain dataset – in our sample of 3739 children surviving to age 5 the death of a mother occurred 200 times and that of a father 302 times. Clearly, these relatively low numbers of cases in the individual categories which we tested may have influenced our final results. We believe, nevertheless, that the findings presented here are important since they address an issue which has so far been dealt with only sporadically.

In terms of methodology, we conducted survival analysis using the Cox proportional hazards mixed-effect models. We calculated the hazards ratios which capture the relative contribution of biological parents and stepparents to their children’s survival. All pair-wise contrasts were evaluated using Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) post-hoc tests separately for maternal and paternal presence. Maternal pair-wise contrasts consisted of a comparison of children raised by their biological mother with motherless children, comparison of children raised by a biological mother with children raised by a stepmother, and comparison of children raised by a stepmother with motherless children. Equivalent comparisons were conducted for the presence of the father (or his absence by death) and the stepfather. We ran each survival analysis under two conditions; 1. as a simple model that included only the effect of parental presence, 2. as a multiple regression accounting for random effects of birth cohort (10 evenly spaced cohorts), birthplace, and fixed effects of parental socioeconomic status and sex of the child.

3. Description of the dataset

Before explaining the outcomes of our analysis, we believe that it is important to use descriptive statistics to demonstrate how many children from the analysed sample survived until their fifth birthday and in what type of family constellation. In total, 2,773 (41.9%) children died within their first five years of life. Out of the 3,845 children who survived, 96.3% were able to celebrate their fifth birthday with their biological mother, 2.3% with their stepmother and 1.4% remained motherless. As concerns the father, 93.9% of the children had their biological father when reaching age 5 while 1.8% had a stepfather and 4.3% grew up fatherless. These percentages do not cover all the children who lost their parents because numerous children who experienced the loss of a parent died before reaching age 5. Altogether 200 children experienced the death of their biological mother (108 of them continued to be raised by a stepmother) and 274 experienced the death of their father. Moreover, 28 children were actually born as half-orphans after their biological father’s death; in total, 302 children spent at least part of their early childhood without a biological father and 80 children lived with a stepfather ().

Table 1. Recorded cases of parental deaths and remarriages.

Even this general description shows that there was a rather profound difference between the death of a mother and that of a father, which confirms previous research. A child lost its father more often than its mother – although female mortality was negatively influenced by possible complications during pregnancy or at delivery (Ory & van Poppel, Citation2013), the husbands were often older and may have been married before. Most frequently, a child lost its mother in the first year of its life, which suggests a connection with giving birth. Almost half of the children lost their mother when they were two to four years old, in a period when a new sibling was usually born into the family given that the average interbirth intervals were approximately 30 months (Fialova et al., Citation2020, p. 20, Citation2018). Naturally, a new pregnancy and childbirth led to an increased risk of the mother’s death. In contrast, the death of a father was more regularly distributed across the first five years. The higher number of fathers who died within the first year of a child’s life results from the fact that 28 children were born to their fathers posthumously.

Even more considerable were the differences between maternal and paternal death in terms of the occurrence of stepfamilies formed after one of the biological parents died. Out of the children surviving until 5 who lost one parent, 62% were raised by a stepmother while only 30% of the five-year-olds had a stepfather. Children up to one year of age had the lowest rate of stepmothers. This is linked to the fact that the father of a child who was only several months old when its mother died may not have managed to remarry before the child reached one year. The father might have remarried later and the child might have eventually ended up living in a stepfamily. Generally, though, those children who lost their mother in their first year of life had the lowest probability of being raised in a stepfamily because these children were simultaneously at the greatest risk of death, as will be demonstrated below. Very often, these children survived their mothers by no more than several days or weeks, which was too short a time for the father to remarry and bring a stepmother to look after the child (Sear & Mace, Citation2008).

As for the fathers, even here the probability of being raised by a stepfather was higher among older children. In the age group of three-to-five-year olds 30% of the children lived with a stepfather, while only one–fifth of the children under 3 grew up in a stepfather family, which was two to three times less compared to maternal orphans. Similar gender differences are also confirmed by research in other regions of Bohemia. In the Nový Rychnov region of the first half of the 19th century, one year after becoming orphaned two–thirds of maternal orphans lived with a stepmother, while only 28% of paternal orphans shared a household with their stepfather (Skořepová, Citation2017, pp. 227–228, Citation2016, pp. 221–222). Research based on the Historical Sample of Netherlands brings similar results (Rosenbaum-Feldbrügge, Citation2020, pp. 48–49).

Before discussing the outcomes of the survival analysis, let us look at the overall picture of orphaned children at different ages according to the parent with whom the child lived and whether the child died or survived.

gives us only a very general overview and displays a certain distortion because most of the children in a given year lived with their biological parent for either a whole year or just part of a year in which the child died. In the category of stepparent and no parent there were orphans who were transferred into those categories only for part of a given year, and after the composition of the family changed, they were transferred to a different category, as will be explained later. Given that child mortality drops quite significantly in inverse proportion to a child’s age, the mortality rate of children raised by a stepmother was lower than the mortality rate of children raised by a biological mother. But this finding does not mean that a biological mother would provide a poorer standard of care increasing the child’s risk of death. It is better to rely on estimated survival probabilities from the Kaplan-Meier curves which treat these possibilities as functions of continuous time. In this time–to–event analysis a single individual can undergo a smooth transition from one category of parental presence to another.

In any event, what clearly shows is that there are changes in the mortality of children over 3 years of age. This rate was usually in the order of tens per thousand, i.e. it was substantially lower than in the first year of a child’s life. At the same time it seems that among children over 3, the family structure in which they were raised ceased to be a factor influencing their survival. Their risk of death tended to be more linked to other, often external, factors (Pavard et al., Citation2005). This would mean that if a child who had lost a biological parent managed to survive to age 3, it successfully overcame this loss which put him at a disadvantage with children raised by both biological parents.

Table 2. Children who survived or died according to their age and caregiver.

These results are also confirmed by child mortality rates according to age and family structure (). They show that it is in the first year of a child’s life that the differences between the individual categories are the most crucial. A weakening effect of maternal loss over time has been also confirmed by the studies analysing data from Quebec (Pavard et al., Citation2005, pp. 217–221; Beise, Citation2005), Krummhörn (Willführ & Gagnon, Citation2013, p. 200) and the Netherlands (Beekink et al., Citation2002). It also appears that losing a mother was indeed more critical than losing a father, although even a father’s death was a relatively major factor of a child’s survival. While the statistics show that roughly one quarter of the children died within the first year of their life, this rate was three times as high for children who lost their mother. This result was to be expected because a biological mother’s care was vital for a newborn and into the first year of life. If maternal care could not be provided, the child usually did not survive. On the other hand, it is surprising that one half of the children under one year died even when the parent they lost was their father. On closer inspection, however, this result is easier to explain, since after the death of her husband, the widowed mother had to take over his role as breadwinner which made it impossible for her to fully exercise her maternal role. Aggravated social conditions in the family may thus have brought about the child’s death. Losing a biological parent had a negative impact on the child’s chance of survival even during the second year of its life. It is only after age 3 that the presence or absence of parents or stepparents ceases to be a factor determining the child’s survival.

Table 3. Mortality rate according to children’s age and presence of biological parent or stepparent.

As regards the presence of stepparents in a child’s life, the differences here are also quite remarkable. If the surviving parent remarried the chances of the child’s survival improved, this trend being more discernible when the child lost a father who was later replaced by a stepfather. The most probable reason is that while a new breadwinner could immediately improve the social situation of the family, the entrance of a new stepmother who might not have had experiences with mother care in the case of a maiden bride and could not breastfeed the child cannot possibly have substantially reversed the negative consequences of losing a mother. On the following pages, we present our research into how the chance of survival at different ages varied depending on a particular family constellation.

4. Relevance of parents and stepparents for child survival in the first five years of age

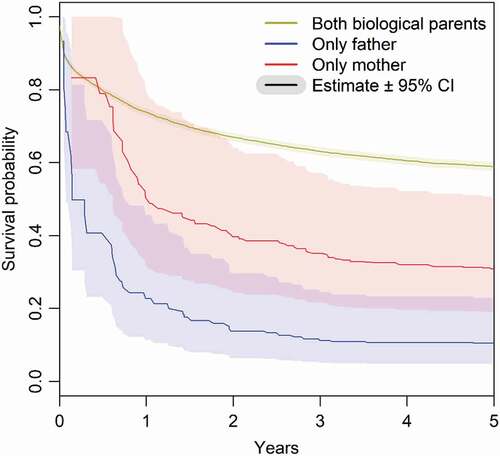

For the purposes of the following analysis we used the Cox proportional hazards mixed-effect model. We tested whether there were any differences in the mortality rate of half-orphans who lost either a mother or a father. We ignored cases of full orphanhood, when a child lost both biological parents, as these were very rare. The analysis showed that those children who lost their mother had a 1.52 times higher risk of death than children who lost their father, but the difference is not significant due to a small number of cases (95% confidence interval = 0.89–2.59, z = 1.55, p = 0.12). Even though having both parents increased the chances of survival, it appears nevertheless that at least during the child’s first year of life its mother’s presence was crucial. Differences in mortality rates between children with both biological parents and those who had only a mother started to appear only after the child was eight months old. After that age, the survival rates of children raised only by mothers start to decrease (see Kaplan-Meier curves in ).

Figure 1. Parental presence.

Let us now look more closely at both basic scenarios which could occur when a child under 5 lost either a mother or a father (). After losing one parent the child continued to be raised by the surviving parent who either remarried and started a stepfamily or remained widowed. It was rare for the relatives to take care of a half-orphan who lost just one parent. Especially in settled families the ties to the original parental farmstead were rather strong and the orphaned children left it only under exceptional circumstances (Vassberg, Citation1998, p. 452).

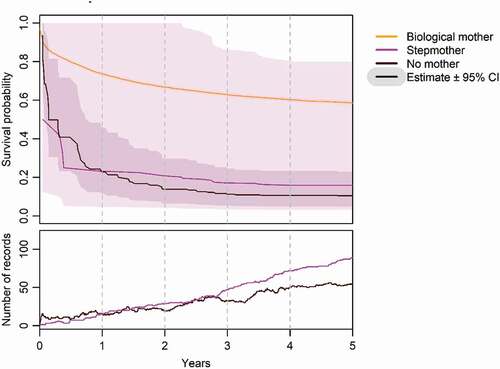

Figure 2. Presence of mother.

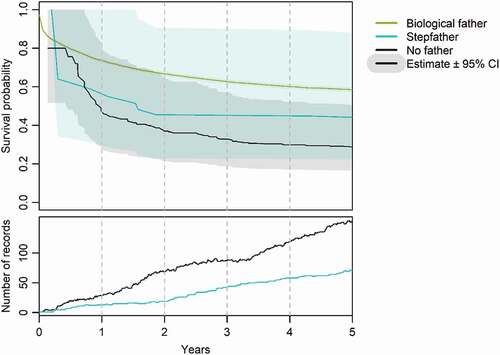

Figure 3. Presence of father.

As mentioned above, the frequency of remarriage differed quite considerably between widows and widowers (Lundh, Citation2007, pp. 378–380). While men preferred to remarry, the situation was far less clear among women, which was caused not only by the attractiveness of widows as potential brides but also by their own interest in remarriage. Usually, it was women under 35 who remarried, not only because their youth gave them higher chances of finding a new partner but also because they themselves were interested in living in marriage and fulfilling their maternal role. Property ownership or rights to use of land were additional factors affecting women’s chances of remarriage. Major changes occurred in the Czech lands at the end of the 18th century to strengthen women’s position in marriage in terms of property tenure. As a result, a wife became the rightful holder of the property upon her husband’s death without the need to appoint a provisional farm administrator, and these widows were not always interested in remarriage which would deprive them of their newly acquired independence (Velková, Citation2010).

Concerning remarriage, there were other differences between widows and widowers which were decisive for the orphans’ chance of survival. The key factor was if and how soon after the biological parent’s death the stepfamily was created, as its main purpose was to recreate a complete family which was able to provide better care than an incomplete one. Widowers with young children typically did not wait too long before they remarried, with the wedding usually taking place within weeks or months. As for the widows, even if we have data on some remarriages two months after a husband’s death, it was not uncommon for widows to wait for a year or two to remarry. The minimum six-month interval between the husband’s death and a new marriage was usually observed also in order to exclude a possible pregnancy with the deceased spouse (Kuklo & Kamecka, Citation2003; Skořepová, Citation2016).

In the case of men, the shorter intervals between the death of a wife and a new marriage were influenced precisely by the ages of the orphaned children. The younger the children left behind by the deceased mother, the more urgent it was for the father to marry again. It is also clear that in the case of breastfed babies somebody had to be found to look after the child immediately (Sellen, Citation2006). The children who lost their mother in the first six months of life experienced the lowest chances of survival (Beise, Citation2005).

In our sample, out of the 34 children who experienced the death of a mother before 6 months of age, only three survived into adulthood. One third of these children died within the first two weeks of their mother’s death. Approximately 60% of these children survived their mothers by a mere six weeks. Interestingly, those three children who survived to adulthood lost their mother at a very early age – two were just two weeks old and one was nine weeks old. Three further children were less than three months old when their mothers died and managed to survive the critical period of infancy only to die at a later age (3 to 5 years).

One of them was Mariana Nosková (1812–1818) from Starý Plzenec whose mother died one day after she gave birth to Mariana, her second-born. Even though the mother died within a day of childbirth, Mariana survived her fifth birthday, and so did her brother Václav (1810–1817), who was two years and four months old at the time of their mother’s death. Their survival, however, cannot be ascribed to the care of a stepmother who entered the family only six months after the biological mother’s death. Their paternal grandmother, Kateřina Nosková (1748–1818), lived in the same house, and presumably could take care of them, but the newborn had to be breastfed. Given that we do not have any evidence of the practice of wetnursing in the region under study, solutions to similar situations were probably found within the larger family. It seems possible that Mariana’s aunt, who also lived in Starý Plzenec and who had given birth to her fourth child only six months before Mariana was born, might have helped save the situation. This example shows that a child’s survival did not depend only on the age at which it became orphaned but also on how extensive and involved was its kinship network (Derosas & Oris, Citation2002). While the care provided by stepparents may have been important for older children, in the case of infants the very first days after the mother’s death were decisive.

In our research we took this into account by analysing the actual situation of the child. From the moment its parent died, the given child was placed in the ‘no parent’ category and either remained there until its death or until its surviving parent remarried, depending on which event occurred first. Hence, the children were included in the stepmother or stepfather category only after they could be reasonably taken care of by a stepparent. Let us now look at how the survival chances differed depending on the types of parental care.

The comparison between the presence of a biological mother vs. stepmother vs. no mother clearly shows that children with no mother had the lowest chance that they would survive age 5. The tests we carried out demonstrated that there was a marked difference between the case when care was provided by a biological mother compared to when there was no mother figure present at all. The child who was raised by its biological mother for the whole first five years of life was four times more likely to survive to age five than a child without a mother. The survival chances of children raised by stepmothers were not as high, but compared to motherless children their chances were still twice as high. This latter result, however, is already on the limit of statistical significance. Furthermore, testing the survival chances showed that even the differences between children raised by a biological mother compared to those raised by a stepmother were statistically significant – children raised by a biological mother were twice as likely to survive as those raised by a stepmother. Estimated pairwise contrasts changed very little when possible confounds (birth cohort, place of birth, sex, and parental socioeconomic status) were included in the model, which shows that the reported effects are robust with respect to particular details of the statistical analysis. The complete results of pairwise comparisons can be found in .

Table 4. Childhood mortality and maternal presence – hazards ratios.

As concerns the fathers, the difference between the presence of a biological father vs. a stepfather was not as substantial as in the case of mothers. Compared to a fatherless orphan, a child who was raised by its biological father was 2.5 times less likely to die, which is clearly a statistically significant result. When a child was brought up by a stepfather, it was 2.32 times less likely to die than a fatherless child, this result being on the limit of statistical significance. As for the survival chances of a child raised by a biological father compared to being raised by a stepfather, here the differences were not statistically significant. Again, adding possible confounds to the model changed the contrast estimates very little The complete results of pairwise comparisons can be found in .

Table 5. Childhood mortality and paternal presence – hazards ratios.

Our analyses also confirmed that the loss of a mother vs. loss of a father led to another notable difference. If a child lost its mother, the probability of its living in a stepfamily with a stepmother increased with age, as demonstrated in the graphs under the Kaplan-Maier survival curves. These graphs show that at age five those children who had lost their mother lived more frequently with a stepmother than with no mother at all. Among the orphans who survived to age 2–3 this model starts to prevail. This age thus appears to be the crucial limit after which the intensity and quality of received care ceases to be vital for the child’s survival. In contrast, there was no such limit when the child lost its father. Moreover, the ratio of orphans raised without a father was steadily higher (even more than twice as high) compared to children raised by a stepfather, regardless of the child’s age. It seems in fact that, unlike widowers, when widows considered a possible new marriage, the age of the orphaned (and at the same time probably also the youngest) child was not a crucial factor. For women, the decision whether to remarry was far more complex than for men. As for widowed fathers, their freedom to remarry or not was considerably restricted by the need to secure care for their young children. The younger the orphans, the more pressing was the need to find them a substitute mother. But the father did not always succeed in improving his children’s chance of survival by remarriage – whether the child survived heavily depended on the age at which it became orphaned.

5. Conclusion

This study focused on the first five years of children living in the countryside in the pre-industrial period, where typically children of this age were at the greatest risk of death. In the Czech lands, almost until the end of the 19th century, 35–40% of children died before reaching age 5. Even if the child mortality rate was obviously influenced by living conditions in general – whether the child lived in town or in the rural society, its parents’ social class and their occupation – the survival of the child in this crucial period of life also depended on the family constellation of the child’s household (Bozděch, Citation2017; Schlumbohm, Citation1994, pp. 154–159).

The main questions which the present study sought to elucidate were whether the loss of a biological parent influenced the child’s chance of survival, and whether losing a mother had more harmful consequences than losing a father. We also tried to find out whether the possible negative effects of a parent’s death could be mitigated by raising the orphan in a newly created stepfamily.

The results of our tests clearly showed that the family structure in which children were brought up in the first five years of their life was indeed crucial for their survival. There were considerable differences between growing up with a biological parent and without one; in addition, losing a mother had different effects than losing a father. In comparative terms, this conclusion is in line with the findings reached by previous studies (Beekink et al., Citation2002; Willführ & Gagnon, Citation2013). It appears, nevertheless, that the specific probability rates of survival after a biological parent’s loss were closely linked to cultural and demographic behaviour patterns which depended on regional context.

Our research has confirmed that, in the Šťáhlavy region, a child raised by its biological mother for the entire five-year period was four times as likely to survive as a child who lost its mother before reaching age 5. Losing a father was less fatal in this respect, but it also had its important consequences. A child whose father was present in the family for the entire five-year period, was 2.5 times as likely to survive as a fatherless orphan. Compared to the outcomes reached by studies conducted at Woerden, Quebec or Krummhörn this value is almost twice as high. This significant finding underlines the importance of gender-based division of labour. The different effects of a biological father’s presence on child mortality detected by the various studies may also suggest that the extent to which gender roles were interchangeable could differ depending on geographical factors such as rural or urban living conditions or social context, and this then led to the different impacts of a parent’s death on the child’s survival probability. The fact that the maternal and paternal roles were gender-specific meant that the death of one of the parents substantially disrupted the existing system of labour division and that in its turn affected the position of the surviving parent (Beekink et al., Citation2002, p. 238; Lundh, Citation2007, p. 377). Although it might seem that a father’s death did not directly interfere with the mother’s role as a carer, in reality losing a husband meant that the mother had to secure the income which was now missing due to the breadwinner’s death. Consequently, she was unable to fulfil her maternal role as thoroughly as when the family was still complete.

A father’s death had the most profound consequences when it occurred during the first year of a child’s life. When the child lost its mother, the first year was the most critical too. In this case, the situation was even more serious, since children were usually breastfed, and with the death of the mother, the child lost its caregiver and source of nourishment. The child’s chance of survival therefore depended on how fast the kinship safety net managed to come up with a solution to this crisis situation.

If the child managed to survive the period when it depended entirely on breastfeeding, a more permanent solution had to be found. Very often it consisted in the father’s new marriage and the formation of a stepfamily. Our analysis has shown that most of the children who lost their biological mother in the first five years of life were raised by a stepmother. It has also been confirmed that a stepmother could indeed improve the child’s chance of survival although only to a certain extent. For those children who lost their mother in their first year of life the presence and care of a stepmother made very little difference. The stepmother’s presence was mainly important for older children.

Interestingly, our data have shown that the negative effects of a biological father’s death on the orphan’s chance of survival could to a large extent be offset by the presence of a stepfather. Even though, similarly to the mother’s death, the father’s death had the most serious consequences when it occurred during the child’s first year of life, among children over two there were no longer any significant differences between children raised by a biological father compared to those who grew up with a stepfather. This conclusion suggests that in this particular case it was not as much the biological ties that determined the child’s survival as the fact that it was raised in a complete family, whose economic security allowed the mother to provide her children with all the necessary care. Generally, the division of labour determined the remarriage needs of the surviving parents – fathers were more in need of a person who would take care of the orphaned children while women often looked for second husband who would secure the family’s livelihood. We consider this finding as especially noteworthy since it not only broadens our understanding of young children’s mortality rate but offers us an insight into the functioning of a rural family in premodern society.

Suplemental_file.docx

Download MS Word (33.4 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors of the special issue, Dr. Gabriella Erdélyi and Prof. Dr. Lyndan Warner, for their helpful comments on the early version of this article which was based on the paper presented at the 3rd European Society of Historical Demography conference in 2019 in Pécs. We are also thankful for the fruitful feedback from the anonymous reviewers and the editor of the journal, Prof. Dr. Jan Kok. The article couldn’t be published without the support provided by the Czech Science Foundation (GACR) - Grant N. 1711983S.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. State regional archives Pilsen, Roman-Catholic parish house of Starý Plzenec, signature 1–37 (born 1651–1834, married 1661–1850 and deceased 1708–1926); R-C parish house of Šťáhlavy, signature 1–8, 12 (born 1814–1834, married 1814–1850, deceased 1814–1877. The Šťáhlavy parish was created in 1814 by separation from the parish of Starý Plzenec. For the purposes of complete reconstruction, other data have been gathered even outside the original parish of Starý Plzenec.

References

- Åckerman, S., Högberg, U., & Andersson, T. (1996). Survival of orphans in 19th century Sweden – The importance of remarriages. Acta Paediatrica, 85(8), 981–985. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb14198.x

- Beekink, E., van Poppel, F., & Liefbroer, A. C. (1999). Surviving the loss of the parent in a nineteenth-century Duch provincial town. Journal of Social History, 32(3), 641–669. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh/32.3.641

- Beekink, E., van Poppel, F., & Liefbroer, A. C. (2002). Parental death and death of the child: Common causes or direct effects? In R. Derosas & M. Oris (Eds.), When dad died: Individuals and families coping with distress in past societies (pp. 233–260). Peter Lang.

- Beise, J. (2005). The helping grandmother and the helpful grandmother: The role of maternal and paternal grandmothers in child mortality in the 17th and 18th century population of French settlers in Quebec, Canada. In E. Voland, A. Chasiotis, & W. Schiefenhoevel (Eds.), Grandmotherhood: The evolutionary significance of the second half of the female life (pp. 215–238). Rutgers University Press.

- Bozděch, L. (2017). Kojenecká úmrtnost ve Staňkově v 19. století [Infant mortality in Staňkov in 19th century]. Historická Demografie, 41(1), 73–86. http://www.eu.avcr.cz/export/sites/eu/.content/files/historickademografie/ HD_41-1_CTP-118s.pdf

- Brown, J. (2002). Becoming widowed: Rural widows in lower Austria, 1788–1848. The History of the Family, 7(1), 117–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1081-602X(01)00099-9

- Campbell, C., & Lee, J. Z. (2002). When husbands and parents die: Widowhood and orphanhood in late imperial liaoning, 1789–1909. In R. Derosas & M. Oris (Eds.), When Dad died: Individuals and families coping with distress in past societies (pp. 301–322). Peter Lang.

- Daly, M., & Wilson, M. I. (1998). The truth about Cinderella: A Darwinian view of parental love. Yale University Press.

- Derosas, R., & Oris, M. (Eds.). (2002). When dad died. Individuals and families coping with family stress in past societies. Peter Lang.

- Dokoupil, L., Fialová, L., Maur, E., & Nesládková, L. (1999). Přirozená měna obyvatelstva českých zemí v 17. a 18. století [Natural growth rate of the population of the Czech Lands in the 17th and 18th centuries]. Sociologický ústav AV ČR.

- Dribe, M. (2000). Leaving home in a peasant society. Economic fluctuations, household dynamics and youth migration in Southern Sweden, 1829–1866. Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Dušek, L. (1985). Obyvatelstvo budyně nad ohří v letech 1701–1850: Historickodemografická studie [population of budyně nad ohří in the years 1701–1850: Historical demographic study]. Ústecký sborník historický, 143–239.

- Dvořáčková-Malá, D., Holý, M., Sterneck, T., Zelenka, J., et al. (2019). Děti a dětství. Od středověku na práh osvícenství [Children and childhood. From the middle ages to the threshold of the enlightenment]. Nakladatelství Lidové noviny.

- Fauve-Chamoux, A. (2010). Revisiting the decline in remarriage in earlymodern Europe: The case of Rheims in France. The History of the Family, 15(3), 283–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hisfam.2010.06.003

- Fialova, L., Hulikova Tesarkova, K., & Janakova Kuprova, B. (2020). The ‘high infant mortality’ trap’: The relationship between birth intervals and infant mortality – The example of two localities in Bohemia between the 17th and 19th centuries. The History of the Family 25 1 94–134 . https://doi.org/10.1080/1081602X.2019.1650792

- Fialova, L., Hulikova Tesarkova, K., & Kuprova, B. (2018). Determinants of the length of birth intervals in the past and possibilities for their study: A case study of Jablonec nad Nisou (Czech Lands) from seventeenth to nineteenth century. Journal of Family History, 43(2), 127–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363199017746322

- Fialová, L. (2000). Poznámky k možnostem studia úmrtnosti obyvatelstva českých zemí v 18. století [Notes on the possibilities of studying the mortality of the population of the Czech Lands in the 18th century]. Historická demografie, 24, 163–188. http://www.eu.avcr.cz/export/sites/eu/.content/files/historickademografie/ HD_24_2000.pdf

- Havlíček, J., Tureček, P., & Velková, A. (2021). One but not two grandmothers increased child survival in poorer families in west Bohemian population, 1708–1834. Behavioral Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arab077

- Hill, K., & Hurtado., A. M. (1996). Ache life history: The ecology and demography of a foraging people. Aldine de Gruyter.

- Horský, J., & Velková, A. (2020). Influence of socio-economic status and household structure on the availability of grandmother care. possibilities of research into the grandmther hypothesis in the Central-Euopean historical family. Historický časopis, 68(5), 769–796. https://doi.org/10.31577/histcaso.2020.68.5.1

- Kok, J., Vandezande, M., & Mandemakers, K. (2011). Household structure, resource allocation and child well-being. A comparison across family systems. The Low Countries Journal of Social and Economic History, 8(4), 76–101. https://doi.org/10.18352/tseg.346

- Kuklo, C., & Kamecka, M. (2003). Marriage strategies in Poland: Social and spatial differences (16th–18th centuries). Historical Social Research, 28(3), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.12759/hsr.28.2003.3.29-43

- Kuprová, B. (2013). Vývoj obyvatelstva na panství škvorec na přelomu 18. a 19. století [Population development at the manor of škvorec at the turn of 18th and 19th century] (Unpublished master´s thesis). Faculty of Science, Charles University.

- Kurosu, S. (2007). Remarriage risks in comparative perspective: Introduction. Continuity and Change, 22(3), 367–372. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0268416007006431

- Lanzinger, M. (2018b). Widowers and their sisters-in-law: Family crises, horizontally organised relationships and affinal relatives in the nineteenth century. The History of the Family, 23(2), 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/1081602X.2016.1176586

- Lanzinger, M. (2018a). Emotional bonds and the everyday logic of living arrangements. Stepfamilies in dispensation records of late eighteenth-century Austria. In L. Warner (Ed.), Stepfamilies in Europe, 1400–1800 (pp. 168–186). Routledge.

- Lundh, C. (2007). Remarriage, gender and social class: A longitudinal study of remarriage in southern Sweden, 1766–1894. Continuity and Change, 22(3), 373–406. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0268416007006443

- Moring, B., & Wall, R. (2017). Widows in European economy and society 1600–1920. The Boydell Press.

- Nováková, O. (2003). Úmrtnost kojenců a mladších dětí v 19. a 1. polovině 20. století [Infant and young children mortality in the 19th and the 1st half of the 20th centuries]. Demografie, 45(3), 177–188. https://www.czso.cz/csu/czso/demografie-revue-pro-vyzkumpopulacniho- vyvoje-1959-az-2010-n-b5146vsfjk

- Ory, B. E., & van Poppel, F. W. A. (2013). Trends and risk factors of maternal mortality in late-nineteenth-century Netherlands. The History of the Family, 18(4), 481–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/1081602X.2013.836457

- Pavard, S., Gagnon, A., Desjardins, B., & Heyer, E. (2005). Mother’s death and child survival: The case of early Quebec. Journal of Biosocial Science, 37(2), 209–227. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932004006571

- Perrier, S. (2006). La marâtre dans la France d’Ancien Régime: Integration ou marginalité? Annales De Démographie Historique, 112(2), 171–187. https://doi.org/10.3917/adh.112.0171

- Rosenbaum-Feldbrügge, M. (2020). Dealing with demographic stress in childhood. Parental death and the transition to adulthood in the Netherlands, 1850–1952. Ipskamp Printing. ISBN 97890326276 Proefschrift.

- Schlumbohm, J. (1994). Lebensläufe, familien, höfe. Die Bauern und Heuerleute des osnabrückischen kirchspiels belm in proto-industrieller zeit 1650–1860. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Sear, R., & Mace, R. (2008). Who keeps children alive? A review of the effects of kin on child survival. Evolution and Human Behavior, 29(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.10.001

- Sellen, D. W. (2006). Lactation, complementary feeding, and human life history. In K. Hawkes & R. Paine (Eds.), The evolution of human life history (pp. 155–196). School of American Research Press.

- Skořepová, M., & Grulich, J. (2017). Palingamní sňatky na území českobudějovické diecéze ve srovnávací perspektivě. Farnosti České Budějovice a Nový Rychnov, 1786–1825 [Palingam marriages in the territory of České Budějovice diocese in a comparative perspective. Parishes of České Budějovice and Nový Rychnov, 1786–1825]. Historická demografie, 41(2), 151–171. http://www.eu.avcr.cz/export/sites/eu/.content/files/historickademografie/ HD_41-2_CTP-146s.pdf

- Skořepová, M. (2016). Ovdovění a osiření ve venkovské společnosti. panství Nový Rychnov (1785–1855) [Widowhood and orphanhood in rural societe. The estate of Nový Rychnov, 1785–1855]. Historický ústav FF JU v Českých Budějovicích.

- Skořepová, M. (2017). Orphaned children in Bohemian rural society. In N. Roman (Ed.), Orphans and abandoned children in European history: Sixteenth to twentieth centuries (pp. 219–250). Routledge.

- Slováková, V. (2018). Životní poměry dívek a mladých žen ve vsi Křenovice v 18. století [The lives of girls and young women in the village of Křenovice in the 18th century]. Historická Demografie, 42(2), 211–237. http://www.eu.avcr.cz/export/sites/eu/.content/files/historicka-demografie/HD_42-2_CTP-102s.pdf

- Srb, V., & Molinová, J. (2003). Střední délka života (naděje dožití) obyvatelstva v českých zemích v 8. až 20. století [Life expectancy of populations of the Czech lands in the 8th to 20th centuries]. Demografie, 45(3), 189–196. https://www.czso.cz/csu/czso/demografie-revue-pro-vyzkumpopulacniho- vyvoje-1959-az-2010-n-b5146vsfjk

- Tymicki, K. (2005). The interplay between infant mortality and subsequent reproductive behaviour: Evidence for the replacement effect from historical population of Bejsce Parish, 18th–20th centuries, Poland. Historical Social Research, 30(3), 240–264. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20762062

- Vassberg, D. E. (1998). Orphans and adoption in early modern Castilian villages. The History of the Family, 3(4), 441–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1081-602X(99)80257-7

- Velková, A., & Fialová, L. (2020). Study of cohabitation of three-generational families on the Šťáhlavy estate in wetern Bohemia in 1820. In P. Łozowski, and R. Poniat (Eds.), Jednostka, rodzina i struktury społeczne w perspektywie historycznej (pp. 321–332). Białystok: Instytut Badaň nad Dziedzictwem Kulturowym Europy.

- Velková, A. (2009). Krutá vrchnost, ubozí poddaní? Proměny venkovské rodiny a společnosti v 18. a první polovině 19. Století na příkladu západočeského panství Šťáhlavy [Cruel landlords, poor subjects? Transformation of the rural family and society in the 18th and in the first half of the 19th centuries]. Historický ústav AV ČR.

- Velková, A. (2010). Women between a new marriage and an independent position: Rural widows in Bohemia in the first half of the nineteenth century. The History of the Family, 15(3), 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hisfam.2010.06.006

- Velková, A. (2012). The role of the manor in property transfers of serf holdings in Bohemia in the period of the ‘second serfdom’. Social History, 37(4), 501–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071022.2012.732737

- Warner, L. (Ed.). (2018). Stepfamilies in Europe, 1400–1800. Routledge.

- Willführ, K. P., & Gagnon, A. (2013). Are stepparents always evil? Parental death, remarriage, and child survival in demographically saturated krummhörn (1720–1859) and expanding Québec (1670–1750). Biodemography and Social Biology, 59(2), 191–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/19485565.2013.833803