ABSTRACT

Close-kin ownership, to own one’s kin, has been researched from the perspective of emancipatory strategies or economic exploitation, hereby overlooking the complexity of kinship bonds in slave societies. This paper addresses the complexities of slavery and kinship and analyses close-kin ownership from the perspective of kinship. In the process of manumission, relationships of obligation were created that continued in life after slavery. When former-owner and enslaved were kin, a layering of obligations took place that extended beyond the widely accepted dichotomy of viewing close-kin ownership as either an emancipatory strategy or economic exploitation. To analyse these concepts and relationships 44 examples of close-kin ownership were selected from a database of 392 manumission petitions from Suriname. In these 44 examples, kin owned enslaved kin. From this sample, five cases of presumed close-kin slavery were identified, kin not only owned enslaved kin, the enslaved were treated as any other slaves and kinship was no extenuating circumstance. By analysing these cases, we have found that close-kin ownership and slavery were interconnected practices that should be studied in unison to grasp the tension between emancipatory strategies and economic gain. Furthermore, the variety in circumstances shows that additional research is needed to continue the creation of a broader framework of kinship and slavery, so that this can be applied to slave societies around the world.

1. The ‘gift of freedom’ granted by family

Kinship and slavery, or kinship in slavery, existed in a contradiction. As Jennifer L. Morgan argued, ‘Slavery destroyed, exploited, and remade kinship among the enslaved through a contradictory claim about African women: that they birthed strangers, or property, rather than kin’ (Morgan, Citation2021, p. 247). Based on Roman law slave status was hereditary through the matrilineal line and thus human relationships were made subordinate to financial gain and principles of property. By denying the existence of kinship bonds apart from the matrilineal line by slave traders and slave owners, a state of kinlessness was forced on the enslaved. Nonetheless, bonds of kinship emerged through births and relationships and influenced life in slave societies. Resulting in the contradiction Morgan described, the enslaved were not and could not be perceived as completely kinless.

As bonds of kinship reached across the enslaved/free(d) divide in society which colonial governments wished to uphold, Penningroth argued that ‘[…] it was through community and kinship, not in its absence, that slaves and masters fought their battles’ (Penningroth, Citation2007, p. 1053). Research from the perspective of kinship can therefore show us what these battles were about. Orlando Patterson identified the denial of bonds of kinship in enslavement as one of the cornerstones of slavery systems and called this process natal alienation and social death (Patterson, Citation1985, Citation2017, pp. 93–104). Therefore, claiming bonds of kinship in both enslavement and freedom pushed against the confines of hereditary slavery (Mustakeem, Citation2016, p. 204).Footnote1 Demanding space for kinship and community meant disrupting and challenging the legal and economic systems that upheld slave societies. These battles fought between the enslaved and masters, who could also be family, defied the overarching power dynamic of the master–slave relationship, and the most direct way to challenge this dynamic was for the enslaved to strive to gain freedom.

The contradiction of kinship and slavery reached further than merely the existence of bonds of kinship among the enslaved. As a historical research perspective, kinship has often been overlooked. Moreover, research on kinship has found itself stuck within the confining dichotomy of benevolent and loving bonds of kinship on one hand, and kin that is inconsiderate, exploitative or uncaring about these bonds on the other (Fatah-Black, Citation2020, p. 625; Penningroth, Citation2003).

Relationships of love and affection were undoubtedly a source of resistance and retaliation among the enslaved and their (free) descendants in the Atlantic world, but not all kinship was supporting or loving in nature (Ben-Ur, Citation2020, pp. 196–199). To truly assess the factor of kinship in slavery, we therefore must integrate the instances in which bonds of blood or affection were subordinate to the functioning of slave society and economy. How could kinship impact the power dynamic of the master–slave relationship? To do so, this article will look at close-kin ownership and close-kin slavery. Close-kin ownership being instances in which kin owned kin. Close-kin slavery representing instances in which those who were enslaved by kin were treated as any other slave and through their enslavement exploited. In the first definition, kinship impacted the master–slave relationship and could even negate it. In the latter, kinship was subordinate to the overarching hierarchy of slave economy, and therefore did not impact or overturn the master–slave relationship. The circumstances of close-kin ownership and slavery display multiple layers of expectations and obligations in slave societies. These obligations could be social, legal and/or financial, but in cases of close-kin ownership familial obligations are added to this, both in enslavement and even in later (possible) freedom. As a result, close-kin slavery and ownership combine the economical and legal aspects of ownership with the reality of the enslaved and their (free) descendants claiming kinship and retaliating against kinlessness.

It was historian Aviva Ben-Ur who introduced the concepts of close-kin ownership and close-kin slavery in her article ‘Relative Property’ (Ben-Ur, Citation2015). Owning kin was and is still treated by historians as a steppingstone to manumission (legal freedom) or a protective measure. As such Neslo, Hoefte and Brana-Shute argued that the consistent mentioning of kinship in Surinamese manumission records − 53% in Brana-Shute’s sample of 943 manumissions that occurred between 1760 and 1828 – is proof of this (Brana-Shute, Citation1989; Hoefte, Citation2008; Neslo, Citation2016).

But Ben-Ur called on historians to inspect the slave family consisting of both enslaved and free members, to argue against the conclusion that close-kin ownership was interim to manumission. She pointed to how: ‘the phenomenon of close-kin ownership can expand our understanding of how deeply the capitalistic values of slavery could permeate every sector of society, including the world of those who lived in or recently emerged from bondage’ (Ben-Ur, Citation2015, p. 5). The process of manumission produced a vast set of sources, which analysed as a corpus can generate new insights into concepts of kinship during and after life in slavery. Although the (legal) process of manumission differed throughout the Atlantic and Indian Ocean, kinship was consistently mentioned in manumission records as either a motivational factor or as a description of the enslaved/petitioners (Brana-Shute, Citation1985; Dantas, Citation2008; Ekama, Citation2020; Negrón, Citation2022). These petitions therefore provide information not only on the family ties of the enslaved but also on free and emancipated people in slave societies. In the Americas, Caribbean and the Indian Ocean, manumission was framed as a gift, meaning that it could only be obtained as a courtesy of the owner. Without their approval, there was no other route to legal freedom. To reflect this, dynamic Patterson and Blackburn argued that manumission led to a relationship of indebtedness to one’s former owner (Blackburn, Citation2009; Patterson, Citation1985).

The theory of gift giving is a central issue in historical research on manumission that originates with manumission being referred to as ‘the precious gift of freedom’ in both legislation and manumission requests. Granting someone their freedom was seen as a gift and ‘kindness’ that could never be repaid, creating a lasting relationship that started after manumission in which the manumittee was culturally and socially in debt to their former owner (Patterson, Citation1985, pp. 210–214).Footnote2 Consequently, this idea of indebtedness interconnects with the emancipatory and economical strategies associated with close-kin ownership. Historians have previously focussed on the question if close-kin ownership was either exploitative or part of an emancipatory strategy, overlooking that these strategies often overlap or succeed each other. Studying close-kin slavery not only shows how far the capitalistic values of slavery permeated every sector of society and therefore the influence it had on the free coloured and Black community, but it also allows historians to assess how the relationship of indebtedness or obligation after manumission translated into practice. Recently more research has highlighted the kinds of debts and obligations that were created through this ideology and the effect that this had on people’s lives after slavery (Chira, Citation2018; Ekama, Citation2020). When bonds of kinship are added to the analysis of these relationships of indebtedness by studying close-kin ownership and slavery, a layering of obligations and expectations can be observed, in which the owner/slave bond was further complicated by a bond of blood and/or affection.

By analysing 44 close-kin ownership cases, this article explores what close-kin ownership and slavery entailed in the second half of the eighteenth century in Suriname. At the basis of this exploration lies argument that economic exploitation and emancipatory strategies were interchangeable and/or complimentary in close-kin ownership and slavery, and that the vastly different circumstances of close-kin ownership and close-kin slavery call for additional research and comparison with other geographical locations. To analyse close-kin slavery, the article offers two types of necessary information to identify close-kin ownership from close-kin slavery in manumission records. The analysis of the five perceived close-kin slavery cases led to the identification of three factors that additionally signal close-kin slavery: the layering of obligations of kin and enslavement, perceptible indebtedness, and the practice of elective kinship.

This article will start out by explaining both the legal framework and practicality on freedom/enslavement and manumission in Suriname. How did manumission work and which documents were produced? What did manumission in eighteenth-century Suriname entail and what do we know about the role kinship played in ‘the gift of freedom’? Based on this historical context, a summary of the used database will be granted to contextualize the chosen close-kin ownership case studies.

Following the concepts of Ben-Ur will be introduced. How can we differentiate close-kin ownership from close-kin slavery? How does a close reading of 44 of close-kin ownership shift our understanding of these concepts? Building on these general findings of the sample, five cases of close-kin slavery will be introduced in detail. Did the gift of freedom granted by kin lead to higher indebtedness, or less? And what expectations can we identify amongst kin?

2. Manumission practices in suriname: gift and obligation

Receiving ‘the priceless gift of freedom’ was the only way for the approximately 50,000 people that made up the enslaved part of society in the second half of the eighteenth century, to legally transition into free society. Only a small part of the enslaved succeeded in this: approximately 0,07%, or 35 people a year were granted their freedom, leading to a population of 330 free Black and people of colour in 1762, which grew to 821 in 1781 (Brana-Shute, Citation1985, p. 213; Hove & Hoogbergen, Citation2001, pp. 306–308).Footnote3 With an enslaved population that fluctuated around 50,000, the free population formed a minority in the colony. Aside from the 330 free people of colour, only 2730 free whites populated Suriname in 1762. The geographical spread of these groups was characteristic of a slave society, 78% or 1881 of the 2390 free people recorded in the colony lived in Paramaribo. The same percentage is seen in the free community of colour, 258 out of 330 people lived in Paramaribo. Enslaved people (forcibly) resided mostly on the plantations that surrounded Paramaribo as the urban centre. A smaller share of unknown size of the enslaved population worked and resided in town, for example because they worked there for their owners, were hired out to town, or their specific skill brought them there (Vrij, Citation1998, pp. 130–132). In 1733, the colonial government in Suriname decided to intervene in the practice of manumission and put the approval of manumissions into the hands of the Governing Council. Until then, manumissions were carried out privately and therefore undocumented, and there was only one regulation imposed on the owner and manumittee: a 1670 edict required that the owner made sure that manumittees were self-sufficient and/or employed so that they would be able to sustain themselves in freedom.Footnote4 In 1733, manumission shifted from a private matter to a government legislated process and each manumission had to be approved by the colonial government.Footnote5 Still, in essence, the process remained a private matter between owner and the enslaved who would come to an agreement long before the actual to the Council was made. That the agreement was settled before it reached the Council is reflected in the denial rates of manumission requests. In the period of 1760 to 1828 the Council only denied 10 requests, and four of these requests were denied based on administrative errors. Only five were definitively denied (Brana-Shute, Citation1985, pp. 189–190).

To begin the formal process of manumission, a written request had to be submitted to the Council, and these documents were then stored in the Council records. The request or petition could be filed by the owner of the enslaved person(s) in question, or by someone on the owner’s behalf when the owner themselves was unwilling or unable to request the manumission themselves. In the case of a third-party petitioner, the Council needed verification of the owner’s permission for manumission. The person filing a manumission request, from hereon called the petitioner or manumitter, therefore was not necessarily the owner of the enslaved person. A share of the obligations created through the manumission process could also be adopted by the petitioner instead of the owner.

The manumission request itself had to include the date of the request, name(s) of the petitioner and/or owner, name of the enslaved, a promise to uphold the obligations dictated by law and a signature. As these documents were handwritten by clerks, petitioners elaborated frequently, which means additional information on the manumittee, and their circumstances can be found. Examples of this are the skill or occupation of the manumittee, family ties, previous residence (plantation or address in town), purchase prices and ages. Although not consistent, elaboration occurred so frequently that profiles of manumitters and manumittees can be made, for the sample and larger database these profiles will be summarized in the next section of this paper.

The obligations petitioner and manumittee agreed to were the legal foundation of these requests. In the request, the petitioner promised to do two things, educate the enslaved in the ways of Christianity and guarantee the financial stability or independence of the manumittee. These two obligations were clearly derived from the main concerns of the Council, namely that freedmen would become either dependent on poor relief or criminals.

Council approval of a manumission request also meant that the person who was to be manumitted would agree to several obligations which functioned as conditions to their freedom. The manumittee and their children should always honour their previous master (and all whites). They could not strike or slander their former master. If the former master should fall into poverty, the manumitted was obliged to help them. If the manumitted died childless, the former master would inherit a quarter of their estate. Manumitted persons could not marry or have sexual intercourse with enslaved people. And last, the line of inheritance would follow that of the so-called Aasdomsregt, which ruled that bloodlines would dictate inheritance. Violating these obligations could lead to fines or in the worst case, the re-enslavement of the manumitted (Brana-Shute, Citation1985, p. 110; Neslo, Citation2016, pp. 100–106). Both sets of obligations for the petitioner and manumitted person would be tweaked and extended in the century to come, all with the purpose of further restriction and control of the movements of those who had been manumitted. The obligations a manumitted person agreed to were a way to remind them that their new status was a gift and a privilege, bestowed on them by their owner and the government. Although now no longer enslaved, the ‘freed’ status was still different from those born free. Being born with slave status therefore meant a life of regulation and control, even if you were one of the very few that succeeded in being manumitted (Brana-Shute, Citation1989, pp. 122–123).

Between 1733 and 1790 the manumission legislation was adjusted five times, with the most important change in 1788.Footnote6 From 1788, ‘the priceless gift of freedom was taxed’. This tax meant a fee of ƒ100 for men above the age of 14 and ƒ50 for women and children. This rule added a financial obstacle to the manumission process as these amounts were significant and could take months if not years of saving. If unable to pay, men were offered to spend 3 years in the colony’s military service, and if they survived, they would be granted their letters of freedom. The taxation of manumissions resulted in a spike of manumission cases from 1786 to 1788 as owners wanting to manumit rushed a larger number of manumissions to save money (Brana-Shute, Citation1985, pp. 139–141).

How this taxation affected the manumission of kin remains to be studied, however it is clear that the additional costs were a burden that was taken up by already free kin. As every manumission was an individual transaction between owner, manumittee and possibly a petitioner, the owner of the enslaved person was able to decide the conditions that would precede the manumission request to the Council. Some enslaved people were asked to come up with just the sum of the tax to gain their freedom, others were asked to buy a substitute slave for themselves thereby compensating the owner’s loss of labour and property. At the end of the eighteenth century, the price for a healthy adult enslaved person fluctuated around ƒ300, but not all owners were willing to accept this ‘market rate’. Once again using the power they had over the people they owned, owners would ask up to ƒ2500 to release someone.Footnote7 Who would pay this sum depended on the circumstances, and information on this is inconsistently mentioned in the manumission requests. An already freed (and often skilled) family member could save up for the payment, money was borrowed from family and friends, or if able, the enslaved person themselves would save extra wages, even combinations of all these methods occurred.

The conditions and obligations put on manumittees in eighteenth-century Suriname were comparable to other colonies who based their legislation on Roman law, especially the other Dutch colonies. Manumission law in Colombo in Sri Lanka had similar expectations when it came to deference, financial assistance and possible re-enslavement (Ekama, Citation2020, pp. 90–91; 96). Most importantly, even though the legal conditions differed in each colony, the outcome was the same, the freedom that manumittees were granted was both conditional and limited. The possibility of manumission reinforced the idea that the (former) owner was both benevolent and sovereign, as only her or his grace made freedom possible (Blackburn, Citation2009, pp. 9–10). This, in turn, created a community of freed people who were all indebted to others, a phenomenon seen throughout the Atlantic, which created societies rooted in inequality (Patterson, Citation1985, pp. 210–214).Footnote8

Finally, it is important to note that in Suriname, women and enslaved people of colour were more likely to be manumitted than men and Black people. The same applied to enslaved people who lived in the city, Paramaribo, as opposed to enslaved people who worked on plantations. Unfortunately, information on the origins of manumittees is rarely stated. The urban context of Paramaribo provided the enslaved living and/or working there with more social and economic opportunities, one could save money by working more, meet free Black people and other people of colour, learn about politics and so on. The opportunity to go into town was also connected to an individual’s skillset. Those who could work independently or performed a trade in which they were hired out and brought back wages had more freedom of movement (Brana-Shute, Citation1989, pp. 48–49). Although these circumstances and therefore the likelihood of manumission are more complex than this, these indicators provide a basic framework on manumittees.

On manumitters, the group of owners and petitioners, Brana-Shute concluded that a great shift occurred over time. At the start of her researched period white males were the majority of manumitters. At the end in 1828, the majority of manumitters were Black or of colour, with more female than male manumitters (Brana-Shute, Citation1989, p. 51). Who was granted the gift of freedom and who received their letters of freedom greatly depended on their ability to create a relationship with their enslaver.

2.1. Database

In Suriname petitions for manumission have been exceptionally well preserved, providing historians with an almost complete set of sources. The database used for this article combines two databases on manumission requests. Dataset I contains 325 manumission requests that manumitted 543 people. Dataset II contains 67 requests that manumitted 101 individuals. Coming to a total of 392 manumission requests which manumitted 644 individuals from 1765 to 1795 in Suriname. This sample represents 65,8% of all known manumission petitions in this period.

Dataset I was created by reading all requests submitted to the Governing Council from sample years every 3 years, starting with 1765 and ending in 1795. Dataset II was created in addition to the first for the purpose of tracing individuals and kinship bonds in manumissions. All the indexes of the inventory numbers existing between the sample years were studied. In these indexes, all requests of those marked as de vrije or another description that might indicate a person of colour or an enslaved person were read to see if they concerned a manumission request. The indexes were also studied to identify people who were already found in Dataset I. The databases were inspired by the work of Karwan Fatah-Black on last wills and testaments in Suriname, and the database created by Brana-Shute (Citation1985) (Fatah-Black, Citation2020). Brana-Shute inventoried all data on manumission request in sample years taken every 3 years from 1760 to 1828. To add on to this extensive dataset I chose to sample years that were excluded from Brana-Shute’s data.Footnote9

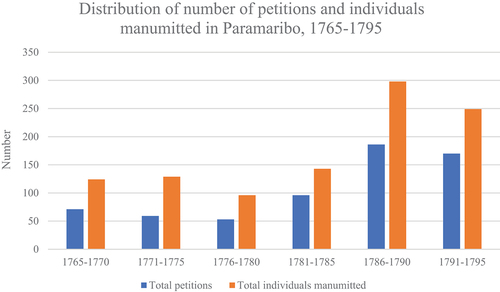

A figure combining all available data on the number of manumissions and individuals can be found in . In this figure, a gradual increase in requests and manumitted individuals can be perceived, a result of rising wealth among the free population of Suriname and the occurrence of rush manumissions to evade the tax of 1788. The work of historians on manumissions in the first half of the nineteenth century in Suriname has shown that this increase would continue to build, with two additional outliers. The first around the turn of the century when British forces invaded Suriname, the second preceding 1804 when the British raised the tax of manumission for the second time and manumitters rushed manumissions to evade this tax (Brana-Shute, Citation1985, pp. 206–207; Hove & Hoogbergen, Citation2001).

Figure 1. Overview manumissions 1765–1795.Footnote10 Sources: unpublished dataset Camilla de Koning (2022) (Brana-Shute, Citation1985, pp. 213–214)., NL-HaNa, 1.05.10.02, inv. nrs: 393 to 461 cover the years 1765–1795.Footnote11

By analysing the complete database 44 cases of close-kin ownership were distinguished from the total 392 cases, manumitting 73 individuals. These cases only include situations in which the owner of the enslaved person(s) referred to the enslaved as kin or family by terms in Dutch. Included were mother, father, parent, sister, brother, daughter, son, grandchild, granddaughter and son. Also included were descriptions such as her sister’s child, indicating a niece or nephew, her son’s child, indicating a grandchild, and the sibling of her father, indicating an aunt or uncle.Footnote12 Dutch norms of what was considered family were forced upon the enslaved, leaving little traces of what the enslaved thought of as family. Even so, it was possible to claim someone as kin, as the colonial government had very little means of verification. Of the total of 44 cases found, 5 cases will be discussed as the source material points at not only close-kin ownership but possible close-kin slavery, defined earlier as the exploitation of enslaved kin as any other slave.

2.2. Context of the database

To situate the 44 cases that have been selected from the two datasets in the broader historical context of manumission in this period in Suriname, a summary of the quantitative findings of Dataset I follows, starting with a short profile of both manumitters and manumittees.Footnote13 The summary of Dataset I spans three themes or subjects with corresponding data. By highlighting the data and conclusions on kinship, request size and conditionality of manumissions, a necessary foundation is offered that will contextualize analysis of close-kin ownership and close-kin slavery in this paper.

The 44 petitions selected for the sample all had a single petitioner, and except for one case, all petitioners were also the (previous) owner of the manumittees. Three women appear multiple times as petitioner, therefore 40 individual manumitters are represented in the sample. below shows how the female/male ratio of petitioners, owners and manumittees in the sample relates to that of Dataset I. Based on this, we can state that women were more likely to own kin and then manumit them, and in doing so created an almost equal female-to-male ratio in manumittees, which is different to the female-skewed manumittee profile of Dataset I.

Table 1. Female-to-male ratio in petitioners, owners and manumittees in Surinamese manumission requests 1765–1795.

Apart from a more balanced female/male ratio, the manumittees in the sample also differ significantly from the whole dataset when it comes to age. At least 44% of the manumittees were described as young, youth or child, as opposed to 31% of Dataset I.

The first subject that need to be explained is kinship and how bonds of kinship are visible in the datasets. Kinship appeared in manumission requests in two forms, either as a motivation for manumission or it was mentioned as a description. Giving a reason for manumission was not mandatory and therefore 28% of the requests compiled in Database I do not specify one at all. Only in 13 out of 325 requests, 4% of the total, kinship was stated as the motivation for manumission. For example, Jan Willem Boom’s request from 1776 stated that it was ‘a mark on his soul that his mother and siblings remain in slavery’.Footnote14 Brana-Shute’s analysis of her sample of 943 manumission requests concerning 1346 individuals from 1760 to 1828 found 67 manumissions that were motivated by kinship, again 4%. In her study, Brana-Shute defined kinship as consanguineal bonds, but also recognized kinship when a manumitter referred to the enslaved woman he was manumitting as the mother of their children.

Apart from plainly stating kinship as a reason for manumission, the pervasive mentioning of family bonds shows that kinship was deemed relevant and therefore connected to the practice of manumission. In 132 requests or 40% of Dataset I the kinship bonds of the manumittees are noted upon. Brana-Shute found this percentage to be 53%, which hints at an increase in the years after 1795. The constant references to bonds of kinship in manumission requests makes them highly suitable to analyse kinship in slave societies.

The second theme concerns the size of manumissions, as requests could petition for the freedom of a single person, or multiple people at the same time. portrays an overview of the distribution of manumission request size in Dataset I and shows that two-thirds of all requests concerned one manumittee.

Table 2. Overview of number of people in the petitions, 1765–1795.

The sample of 44 cases shows a similar spread in request size, 29 requests manumitted one person, the remaining 15 manumitted two or more people with the largest group counting nine manumittees.

When analysing the 108 group manumissions found in Dataset I, it is obvious that kinship was a significant factor in these manumissions. Of the 108 manumissions that involved more than one person, 83 were groups of family members. Of these 83, 77 groups were mothers and fathers manumitted with their children and six groups of siblings were identified.Footnote15 By manumitting a family, a manumitter acknowledged the kinship ties of the enslaved, and Dataset I demonstrates that women were more likely to do so: 29% of family groups were manumitted by a woman, as opposed to 14% of the total of petitioners being female as depicted in .

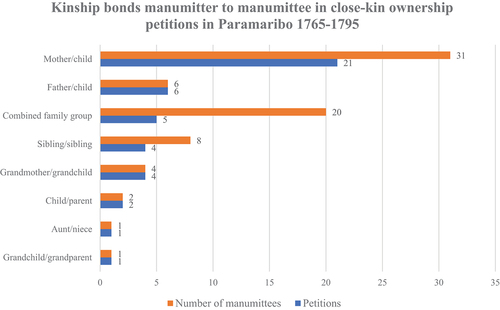

, depicted below, visualizes the kinds of family bonds that were found in the total sample of 44 close-kin manumission petitions that were found from 1765 to 1795. Kinship bonds are stated as manumitter/manumittee, for example a mother manumitting their child, a sibling their sibling. The column ‘combined family groups’ refers to five manumissions in which multiple bonds of kinship were named. Quassi manumitted his sister Aba and his son Quassi.Footnote16 Catharina van Dikie Samson and Betje van Pardo manumitted their daughter(s) and grandchild(ren).Footnote17 Jan Willem Boom freed his mother and three siblings, and lastly Cato van Vuist acquired freedom for her sister and two cousins.Footnote18

Figure 2. Kinship bonds of manumitters in close-kin ownership petitions in Paramaribo 1765–1795. Unpublished dataset Camilla de Koning (2022).Footnote19

The 44 manumission cases and family bonds depicted above provide a baseline of the kinship bonds found in close-kin manumission between 1765 and 1795. Every manumission request of these 44 cases was petitioned by a single owner, together manumitting a total of 73 individuals. The biggest share of this sample, 30 out of 44 cases, depict mothers and fathers manumitting their child(ren) out of affection. Out of 23 mothers, 10 manumitted 2 or more children. Two mothers, Catharina and Betje mentioned above, also manumitted grandchildren at the same time. All fathers manumitted a single child.Footnote20

Remarkably, all sibling/sibling cases found in the whole sample are cases of close-kin ownership and are therefore part of the sample. There are four straightforward cases of siblings manumitting their sibling(s). Three other cases of siblings manumitting sibling(s) alongside other family members are part of the combined family group category.

The last theme and representation of data covers a particular kind of manumission, what I call ‘conditional sales’. In these conditional sales, new owners were only allowed to purchase the enslaved person(s) if they promised to legally manumit them. The promised manumission had to occur as soon as possible, after a stated amount of time, upon the death of the new owner or when the enslaved child came of age. These manumissions under condition make up 25% of Dataset I and represent a kind of ownership that was based on a deliberation of manumission. Of the sample of 44 cases, 25 explicitly state that the purchase of the enslaved person(s) was sought after with the intention to free them as soon as possible. Amongst close-kin owners, these conditional sales therefore occurred more than twice as much than in the sample, 57 compared to 25% respectively.

The sample of 44 cases taken from the two datasets thus represents a significant subgroup in the data. When kin manumits kin, the manumitter is more likely to be female, petitioner and owner are the same, most manumissions freed mothers with children high depiction of intention to manumit is apparent in the requests. Before differentiating between close-kin ownership and close-kin slavery, it has already become apparent that 57% of these manumissions were intended as ‘stepping stones’ to manumissions. But this summary excludes the conditions that set apart the five cases that will now be discussed: that of dependency and obligation. Which of these cases demonstrate an underlying basis of economic exploitation instead of an emancipatory strategy? How can we differentiate between close-kin ownership and close-kin slavery?

3. Close-kin ownership and close-kin slavery: framework and identification

In her article on close-kin ownership published in 2015 Ben-Ur introduced two new concepts. The first being close-kin slavery, a situation in which kin owned kin, not with the intent to free them but to treat them as any other enslaved person with the purpose of capital gain. The second concept was elective kinship. Elective kinship was the process of favouring one family member over the other, meaning some kin would be kept in slavery while others were manumitted. Elective kinship is compared by Ben-Ur to how white planters could choose to claim their kinship ties to those in slavery, but only to those they deemed worthy, which led to people of colour copying this behaviour (Ben-Ur, Citation2015, p. 23).

To distinguish close-kin ownership from close-kin slavery, two types of information are crucial, the dates of ownership and circumstances of labour. Unfortunately, manumission requests do not consistently reference these data, especially regarding labour circumstances. To prove ownership before manumission could be approved, the petitioner provided annexxen to the Governing Council, but after checking these documents, they were returned to the owner without consistently noting these dates in the petition. By chance two other kinds of dates are mentioned in the petitions: the manumission date of the petitioner, and/or the purchase date of the enslaved. The manumission dates of the petitioners show how long it took people from the time of their own manumission to first purchase kinfolk who had remained in slavery and then find the funds to manumit them. The second set of dates that can help to distinguish close-kin ownership from close-kin slavery are purchase dates and these purchase dates can also be deduced from death dates of former owners. The death of a slave owner could have meant that their estate was sold off in parts, which was an opportunity for those wanting to purchase their kin. Especially as buying from an estate could have meant the opportunity to buy a family group.

Twelve sets of data were found in the petitions, and they show an average of two years from either death of the former owner or from date of purchase to a manumission request.Footnote21 A logical interval as the possibility of buying parts of an estate was opened after a year and six weeks, the period in which inheritors had to claim their share. After the purchase, funds had to be gathered and then filing a petition could take one, two or three sessions, up to three-quarters of a year (Brana-Shute, Citation1985, pp. 177–182). Longer intervals of close-kin ownership do not necessarily point at close-kin slavery as the speed of manumission relied mostly on administration and verification. These dates confirm that the main share of close-kin ownership moved towards manumission without instances of close-kin slavery (Fatah-Black, Citation2020; Negrón, Citation2022; Neslo, Citation2016).

4. The layering of obligations: enslaved kin

Analysing close-kin ownership as either an economic or emancipatory strategy from the perspective of manumission, especially after 1760, confronts us with the influence legal requirements had on close-kin ownership. Enslaved people could not be manumitted if they would be at risk to fall into poverty. The colonial government feared they would become ‘a burden to society’ in the way that those newly manumitted would become dependent on poor and parish relief. This fear was not just articulated in Suriname but also in colonies in both East and West (Ekama, Citation2020). The condition of self-sufficiency, either through having been taught a trade or being granted an inheritance or sum of money, was the first condition ever put on manumission and this principle was re-affirmed through additional legislation in 1760.Footnote22 Until that year the Governing Council had found that too many petitions had not lived up to this condition, and a rising amount of manumittees had not been taught a trade at all. Therefore, another option was created, manumittees either had to have mastered a skill or would need to be granted a sum of money (inter vivo or postmortem), or someone had to pose as their guarantor, an individual would ensure their financial stability. No minimum amount or special criteria was included in the amendment but from 1760 onwards, every manumission petition included a statement that the ‘1760-conditions’ were met. Connecting this requirement to close-kin slavery adds a new layer to the concept and gives rise to the question: is obliging enslaved kin to work for their own manumission close-kin slavery?

Based on these information and criteria, five petitions that appear to include instances of close-kin slavery were found in the sample of the 44 close-kin ownership cases: Jan Hendrik in 1774, Dorothea in 1780, Fenecia in 1787, Welkom in 1791, and Santje in 1796.Footnote23 Their requests do not only include details on the length of ownership but also the circumstances of (expected) labour. The circumstances of each family are so different that each case will be discussed. The cases are not ordered chronologically, but according to how they relate to the following concepts: the layering of obligations of kin and enslavement, indebtedness, and elective kinship. The cases of Fenecia, Santje and Jan Hendrik will be discussed more in-depth.

The first case of close-kin slavery that will be discussed is that of de vrije Dina van Stolting, who in 1791 manumitted her young son Welkom on the condition that he must serve her for the remainder of her life.Footnote24 The petition does not record how Welkom had to serve her after his manumission. At the time of manumission, he is described as a boy, with no apparent skills or trade. Furthermore, it was Dina who posed as his financial guarantor and explicitly stated that she had purchased and manumitted him out of motherly affection. Dina herself was manumitted with her daughter Marianne in 1786 upon the death of her owner Philips Stolting, which meant that Welkom, a young boy, was left behind in slavery at that time.Footnote25 Within four years, Dina had managed to purchase and manumit her son and was able to fulfil the conditions of guarantee. Without additional information on their lives several questions cannot be answered. Was Dina’s mention of servitude intended as close-kin slavery? Or was Dina safeguarding Welkom’s closeness by ensuring the court that he would not only be cared for by her but his occupation would be caring for his mother? By tying Welkom to herself in servitude for the remainder of her life, was she requiring him to repay his gift of freedom? And should we see this as an example of economic coercion, or the fulfilment of a natural filial obligation, namely, caring for one’s parent(s) as they aged?

Analysing the petition for Dorothea’s freedom from 1780 develops this line of thought. Dorothea was manumitted by Samuel Townshend out of ‘special affection’, making it likely that he was her biological father.Footnote26 Townshend was a British plantation owner who was part of the plantocratic elite in the Dutch colony and who died 3 years after manumitting Dorothea. To fulfil the conditions of the 1760-law, Townshend granted Dorothea ownership of her mother America and brother Fredrik. In a way, they were her bail in lieu of a sum of money. It was explicitly stated that the labour of both mother and son should be rented out for Dorothea’s profit and that America and Fredrik should care for Dorothea until she came of age.Footnote27 Fredrik and America were held in close-kin ownership and are the example in this sample of records that most resembles Ben Ur’s concept of close-kin slavery. No manumission request for Fredrik and America was found in the following years, but did their situation caring for Dorothea mean being enslaved for someone else’s capital gain? Their family was kept together, but divided by legal status, and represents a situation often seen in slave societies. As Blackburn enquires, was being held in close-kin ownership by a kin member better than the prospect of separation? (Blackburn, Citation2009, p. 10)

Some argue that granting a child ownership of their parents was an attempt to undermine parental authority, or a way to divide and rule enslaved families (Ben-Ur, Citation2015, pp. 15–17). The analysis of this database leads me to argue otherwise. Manumitting children instead of their parents could be seen as a strategy for turning an enslaved family into a lineage of freed people. Especially regarding property, removing children from enslavement meant that property could be safeguarded (Fatah-Black, Citation2018, Citation2020). Parents and especially mothers were charged with the care of their children in and out of slavery and societal standards expected children to care for their ageing parents in a similar matter when they were able to do so. The case of Dorothea for example thus not directly reflect a ‘coercive economy’. Instead of handing their earnings over to their owner, America and Fredrik were now working to support a family they were part of. As Morgan argued in her book, we must continue to consider the capacity of women and mothers to understand that ‘the market would forever undermine Black people’s social connections’ (Morgan, Citation2021, p. 171). And if not undermine, always influence.

The examples of Welkom and Fredrik and Amerika bring the subject of dependency and morality connected to kinship to the forefront. Family or not, the enslaved were dependent on their owner, and the promise of freedom was never guaranteed until letters of freedom were handed out. In the contradiction of slavery and kinship, expectations and obligations connected to kinship complicated relationships, and we must face and integrate these complexities in our research. The following example of Venus’ manumission reflects this and supports the argument that economic and emancipatory strategies are not two different paths, but interconnected matters in close-kin ownership.

As an enslaved girl, Venus was sold for ƒ500 to her biological father Barend by her owner Dikie Samson, on the condition that he would manumit Venus.Footnote28 The matter was discussed with her mother Catharina who was then still enslaved, and she agreed. But in 1775, several years later, Catharina had discovered that Barend, in her opinion, was not behaving ‘as a father should’ and that ‘without knowledge of her, the mother of Venus, he was offering and bargaining to sell Venus and her daughter’. According to Catharina, this was not only against the laws of the colony but against the natural duties of a parent towards their children.Footnote29 To resolve the situation and guarantee the freedom of her child and grandchild, Catharina offered to buy Venus, either for the original sum of ƒ500 or after an appraisal (which would define Venus’ perceived economical value in the eyes of the colonial government).

Barend’s response displays both the contradiction of kinship and slavery and the restrictions of the binary of economic/emancipatory strategies. In his rebuttal, Barend refused to claim or acknowledge Venus as his kin: ‘If the black woman Venus is a daughter of the petitioner or not (yes or no), the contrary can be claimed as none of her behaviour or actions comply with what is owed by children to their parents.’Footnote30 It is remarkable that even though Barend was unwilling to acknowledge his bond of kinship to Venus and her daughter, he did point at the obligations children had to their parents, enslaved or not. He further stated that if Venus would have wanted to claim her promised freedom ‘she should have adjusted her way of life to this’, with ‘this’ referring to working to obtain her freedom.Footnote31 According to him, Venus had caused him great sorrow daily. By calling both Venus’ behaviour toward him as both owner/father despicable and unworthy of freedom, Barend used both sets of obligations and expected deference to him to prove his point. In the first argument, he referred to her obligations as a daughter, but his later argument referred to her obligation as a slave. The rude, dishonest, or ‘malevolent’ ways of both Catherina and her daughter Venus are the core of his letter, making them both unworthy of a gift only he could bestow upon them. It therefore seamlessly joins in with the overarching ideology that manumission or freedom is a gift one must be worthy of, or it will be taken away, and in this a promise made by kin is not more trustworthy than that made by any other owner (Blackburn, Citation2009).

It is in this case that we see to which extent emancipatory and economic strategies overlap and complicate matters. Barend was willing to buy his daughter under the promise that she would work in close-kin slavery and hand over her earnings, leading to her manumission. Again, this situation of expected labour in close-kin ownership confronts us with questions: was this close-kin slavery or an idea of indebtedness and repayment? Did Barend expect Venus to reimburse him for her purchase price or was his incentive to make a profit? The unique insight this case offers is the contrasting view and argumentation offered by Catharina as mother and grandmother. Barend refused to accept the original purchase price or more for Venus, making it clear that either repayment of the 500 guilders nor a profit would satisfy him. But his refusal was based solely on Venus’ misconduct, not just the fact that she did not hand over her earnings. Her misbehaviour and disrespect had, in his view, made her debt to him irredeemable. Venus and her daughter Johanna were eventually manumitted 12 years later in 1787 after Catharina managed to buy them from a third-party owner, Jean Jacques Rouleau. Based on Barend’s comments, it is very likely that until that time both Venus and Johanna were held in close-kin slavery, not the close-kin ownership that the women were once promised.Footnote32

5. Diana and Santje

Emancipatory strategies could not exist without functioning within the slave economy. A legal manumission was obtained by a financial and legal transaction, approved by the colonial government. Ben-Ur argued that this was ‘following the exploitative logic of a slave economy’, but just as with close-kin ownership, internalisation of the economic values of the slave system comes in gradients.Footnote33 The following example will show that apart from concerns on economy and enslavement, the factor of kinship and the obligations attached to it were at the centre of close-kin ownership and perhaps slavery in general. Letters of freedom could not be granted without expectations, confirming the overarching dynamic that held the free community of descendants in perpetual indebtedness to their former owners.

In 1796 de vrije Diana van Adam approached the Governing Council following a conflict with her daughter. Diana herself was manumitted in 1786 and first bought and manumitted her son Adam baptised as Iszaak in 1794.Footnote34 In 1791, she purchased her daughter named Santje from the plantation De Drie Gebroeders.Footnote35 The whole family originated from this plantation and as such they represent the only people in the sample who found their way from plantation to manumission. Diana had purchased Santje with the objective to manumit her, but Diana had loaned the sum of money to purchase Santje and unfortunately had not been able to resolve this debt, which lead to insufficient funds to procure Santje’s letters of freedom. Diana’s solution was simple, she requested Santje to work so they could pay off her purchase sum and purchase letters of freedom together.Footnote36 But this, Santje refused. The petition reads that Diana ‘to her sorrow had to experience that her daughter did not respond with the expected obedience to her natural obligation’. This natural obligation is not only compensation for the (financial) trouble Diana had gone through, but filial obligation. The confrontation reached a boiling point when Santje ‘Approached the petitioner [Diana] with malicious ingratitude, Yes! With disrespect and contempt, in such a way, that she [Santje], with the help of another, has withdrawn herself from her obligations as a slave.’Footnote37 Santje left Diana’s residence and when ‘kindly reminded’ of the sum that needed to be paid responded with ‘grand insolence’.Footnote38

Diana’s reasoning argumentation shifted from filial love to slaafsche verplichting, the duty of the enslaved. While her concern first lay with her daughter, her discontent shifted to the perceived infringement on her property rights of a person, namely her daughter Santje. It is this shift that Penningroth conceptualizes in his article on the claims of kinfolk. Owners would attempt to manipulate kinship rules to tighten their grip on those who were dependant on them (Penningroth, Citation2007). Diana, by shifting her strategy of manipulation from owner to kin and back, established both her expectations of Santje as daughter and slave. Can we define this as ‘coercive economy’ or a reasonable expectation? The lack of obedience and consideration of her daughter leads to Diana no longer referring to Santje as her daughter, but her property.Footnote39 This switch in strategy, in addition to the earlier example of Barend presenting his argumentation, shows that in life after slavery in Suriname emancipatory strategies were complex and different, and part of the complexity of slave economies. Moreover, these findings tie into the overarching debate on how kinship and property relations overlap. Family structures, especially patriarchal ones, conveyed a sense of ownership from parents over children. The cases mentioned bring these power structures into a legal context in which hereditary slavery stood at the core, but close-kin ownership could also flip these more ‘traditional’ structures from parent over child, to, for example, child over parent as seen in Dorothea’s case, creating new perspectives.

6. De vrije Jan, Jan Hendrik, and Dickie Samson

As has been touched upon in the cases of Dina and Diana, evidence of elective kinship practices is clearly present in the sample. It is hard to deduce why certain family members were manumitted before others, but the tax on freedom that was instigated in 1788 did financially limit families. The manumission practices of Jan Samson portray elective kinship and tie into the relationships of obligation and indebtedness that stood at the heart of close-kin ownership.

De vrije Jan Samson was a man who was once owned by the widow Hester Moll, born Adamse. According to Jan, he was manumitted after her Moll’s death in 1757, at which time he was also granted the ownership of his son Kwauw.Footnote40 Jan Samson is the first level of a so-called chain manumission and representative of the principle I articulate as ‘those who have been manumitted manumit’. After his manumission Jan became a manumitter, and these manumittees became manumitters in their turn, thereby forming a chain, which is depicted below in .

Figure 3. Kinship and manumission diagram de vrije Jan Samson.

Upon his death in 1775 and through his testament Jan Samson manumitted three people: his sons Dickie and Jan Hendrik (Kwauw), and his slave Brutaal. With the help of solicitor Dirck van der Meij, both Jan’s sons Dickie and Jan Hendrik (Kwauw) petitioned the courts for their freedom. But the requests and multiple declarations that followed showed that Jan Hendrik had already petitioned for his freedom back in 1774.

To summarize, Jan Hendrik was given to his father at the time manumission by widow Moll. Jan Samson argued that he was given ownership of his son for two reasons. Firstly, it would ensure that Jan Hendrik would care and support him for the remainder of his life and secondly, it would allow Jan to raise his son, while simultaneously teaching him the trade of carpenter.Footnote41 Jan promised his son his freedom at an undefined date, which became a problem when Jan Hendrik left for the Republic in 1772 ‘out of love for the Christian religion’.Footnote42

Jan and Jan Hendrik’s case is conceptually like that of Dina van Stolting and Welkom. Although Dina was not given her son, she bound him to her in service, and Jan’s declaration on the reasoning behind being granted his son sheds a light on her actions. What both Jan and Dina demonstrate is a social hierarchy of dependence, only the dependence on and of family is added in this equation (Ekama, Citation2020). Although Welkom and Jan Hendrik differed in legal status, their circumstances were comparable, both were held in close-kin ownership and therefore in a state of semi-freedom and thereby semi-enslavement.

In his original case in 1774 January Hendrik argued that because he was baptized in the Republic and promised freedom, the Council should grant him his letters of freedom. His father clearly disagreed and wanted Jan Hendrik, who he consistently referred to as Kwauw, to return to his duties as a son, to provide and care for his aging father. As Jan Hendrik had refused this, Samson resorted to hiding his Dutch proof of baptism and collected his son’s wages behind his back as if he was still officially enslaved. The core of this conflict lay in the control that Jan wished to have over his son. If he would not provide for his father out of filial love, he would be forced to do so as an enslaved person. This tactic reproduced the same switch of strategy, from kinship to property, as seen with Diana and Santje, Barend and Venus. The Council agreed with Samson, and Jan Hendrik had to serve his father until he died, Jan Hendrik’s letters of freedom were provided in 1777 at his own cost.Footnote43

Jan Samson and his son Jan Hendrik found themselves within the contradiction of kinship in slavery, where the obligations of family and slavery became a complex puzzle. If this was close-kin slavery, can we consider this a separate form of enslavement? Not in terms of mildness, but in its complexity. In life after slavery, Jan Samson allowed his son/slave enough leeway to go to the Republic and return, apparently unpunished. According to Samson, Jan Hendrik’s crime was no longer caring for him, which after providing his upbringing and teaching him a trade, sounds similar to the grievances of Diana regarding Santje. Could those who held open the door to life after slavery for their kin count on their cooperation and effort? Could those who owned close kin break themselves free from the dominant ideology that freedom was a gift, and with a gift comes an obligation to repay? In the eyes of Jan Samson, Jan Hendrik and his service were a gift he was entitled to, and although Jan Hendrik was never a part of the process that made him indebted to his father, Samson believed that Jan Hendrik’s debt could never be repaid in his lifetime.

Jan’s other son, Dirck, also had a problematic path to freedom. His case exemplifies some of the intricacies historians have to consider when analysing elective kinship. His father had made Dirck or Dickie, his freeborn son, his universal heir. But upon sorting through his testament and belongings, executor van der Meij was not able to find proof that Dickie’s mother, Bettie, was ever manumitted. All the executors had found was a signed note by Samson that Bettie was freed, making her a piki nyan, an unofficially freed woman. The Council’s data also did not possess proof of manumission, making both Bettie and Dickie officially of enslaved status.Footnote44 The situation was complicated further by the fact that Samson’s estate was in debt and the deceased had ordered that his house and enslaved people could not be sold. To manumit Dickie, a bargain was struck. Before passing away, Bettie had another son, who, following Bettie’s status, turned out to be still enslaved. To raise the money needed to manumit Dickie and for him to take on his role as universal heir, his half-brother was sold at a public auction. No name is provided for his brother, but the ‘election’ of his brother as kin meant that he was (re-)enslaved after previously living in a state of freedom.174

The different gradients or forms of close-kin ownership and close-kin slavery depicted in this article closely align with what Patterson argued about different modes of release (Patterson, Citation1985, pp. 219–239).Footnote45 While some enslaved people ‘achieved full manumission at once, others attained it over time, still others remained for the rest of their lives in a twilight state of semi manumission’ (Patterson, Citation1985, p. 219). This is clearly present in close-kin ownership and slavery situations. In these arrangements, kin – as owner – was able to determine what the exact arrangement would be, and which factors or actions would lead to the initiation of manumission. Obligations associated with kinship were made a part of these agreements and complicated the conditions of these kin-manumissions more than in non-kin cases. A different ‘mode of release’ was connected to the expected outcome of manumission. The legal system of Suriname enabled these partial or conditional manumissions, confirming the power of the owner over their manumittee, in these cases kin, no matter what ‘mode’ of manumission was promised. No matter if the argumentation was based on kinship or enslavement, the concept of indebtedness and thereby property was the basis of close-kin slavery.

7. Conclusion

Families divided by slavery, some free and others in enslavement, are treated by historians as though they were in transition. Especially when one family member owned another enslaved family member, this must have been a temporary condition, the ambition must have been to eventually live together in freedom. But did kinship impact the owner–slave relation in such a way that it changed the dynamic of slave ownership to not strive for exploitation but release from slavery? To begin at answering this question, this article explored what close-kin ownership and close-kin slavery entailed in the second half of the eighteenth century in Suriname.

Kinship was pervasively mentioned in manumission requests in Suriname, namely in at least 40% of the requests for letters of freedom filed from 1765 to 1795. The references to kinship in these documents affirm the importance of kinship as a factor in manumissions. However, in the dataset of 392 manumissions analysed for this article, kinship was only mentioned explicitly as motive in 13 cases. By broadening the search for kinship motivated manumissions from not just the reason that was stated to also looking at the claimed kinship bonds in the request itself, the perceivable presence of kinship bonds increased. Forty-four cases in the dataset proved to be cases of close-kin ownership.

In this article, the complexity of and variety in kinship relationships in and out of enslavement has been explored, and through this light has been shed on the understanding we have of slave societies and how relationships were complicated by the capitalistic values that laid at the basis of slave societies and impacted family life. By analysing cases of close-kin ownership and slavery I have started to trace and depict how those living in slave societies viewed the concept of kinship, used, and moulded it to their own benefit, and finally how easily claims on the basis of kinship and enslavement (possession) were interchangeable to safeguard life after slavery. Those who owned kin and consequently manumitted them were mainly women, who depicted a high intention to manumit from the moment of purchasing their kin on. As opposed to the larger datasets in which women were more frequently manumitted, women and men were just as likely to be manumitted by kin through close-kin ownership.

Through presenting that the experience and outcomes of close-kin ownership relationships varied widely, this article has opened possibilities for comparison of close-kin ownership and slavery in other slave societies. It has done so by indicating that two types of information are most useful to identify close kin slavery. Firstly, information on the dates of ownership and secondly the circumstances of labour. In addition to this, three factors that signal possible close-kin slavery were established that can be used outside of the geographical scope and time span of this article, namely the layering of obligations of kin and enslavement, perceptible indebtedness, and the practice of elective kinship.

Research on close-kin ownership and slavery should be rooted in cross-referencing source material. The interlinked nature of manumission records makes it possible to gather the data needed to differentiate close-kin slavery from close-kin ownership. When supplemented with sources that contain more information on the labour circumstances of enslaved kin, it will become possible to trace this phenomenon through history. Doing so not only allows us to understand the complexity of kinship in and out of slavery, it will also form a necessary understanding of the extensive bonds of obligation and dependence that came from (close-kin) manumission practices in (former) slave societies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Full argument by Sowande Mustakeem, p. 204: ‘Creating kinship in these conditions is to refuse the structures of commodification that undergird not just racial slavery and human hierarchy, but indeed the edifice of colonial extraction that fuelled early modern capitalism’

2. Patterson argues on page 213: ‘If the relationship is an ongoing one, it is clear that repayments both complete and initiate a cycle of gift exchanges in a continuous dialectical progression that moves forward lineally for the two persons interacting, but concurrently spreads out laterally to all persons interacting in the total system of prestation – in other words, to the community at large’

3. People of color were categorized by the colonial government of Paramaribo, Suriname, either as zwart, black, or gekleurd, coloured. Within the categorization ‘coloured’, common descriptions were mulat, mulatto, or musties, musties. These categorizations were highly political and therefore cannot be assumed to be an accurate description of people. As a means of functioning in the colonised society people of colour referred to themselves in these terms, therefore, these terms may be found in (translated) citations as an example of terms used at that time in history.

4. Smidt en Lee, Plakaten, ordonnantiën en andere wetten uitgevaardigd in Suriname, 1667–1816, 56. (Placards, ordinances and other laws enacted in Suriname, 1667–1816).

5. Smidt en Lee, Plakaten, ordonnantiën en andere wetten uitgevaardigd in Suriname, 1667–1816, 411. Article 350.

6. (de & van der Lee, 1973) Articles: 350, 394, 573, 597, 663, 720 (Neslo, 2016, pp. 104–106);

7. For example: NA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 401, scan nr. 581, folio nr. 272. Petitioner: de vrije negerin Diana van Fromant. Manumittee: Manthe (1769-02-23).

8. In his introduction in the book Pathways to Freedom Robin Blackburn argues that: ‘The powerful negative associations of New World slavery could not be washed away by manumission but instead remained a burden. This was especially true so long as many of African descent remained in slavery – but remained as a legacy even after general emancipation.’: 9.

9. See reference list for an overview of inventory numbers.

10. The average ratio of the number of individuals to petitions in these thirty years is 1:1.7. This ratio is skewed by the manumission of several large groups of manumittees and the pending legislation in 1786 to 1788 which raised the cost of manumissions. On the overall trends in distribution and frequency of manumissions see (Brana-Shute, 1985, pp. 201–208: 213–214).

11. National Archives The Hague, (hereafter NL-HaNA), 1.05.10.02, Inventaris van het digitaal duplicaat van het archief van het Hof van Politie en Criminele Justitie en voorgangers, in Suriname, 1669–1828. The years 1768, 1770, 1773, 1776, 1779, 1782, 1785, 1786 and 1788 have not been catalogued so they have not been included.

12. Original texts including spelling variations: moeder, vader, ouder, broeder, zuster, zoon, dochter, kleinkind, kleinzoon and kleindochter.

13. These quantitative findings in the figures below relate only to Dataset I and the 325 requests studied in this dataset, as Dataset II contains a selected number of manumission requests based on kinship criteria, not all manumission requests available for the years studied, making Dataset II unsuitable for comparison.

14. NA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 417, scan nr. 93, folio nr. 44. Petitioner: Jan Willem Boom. Manumittee: Nanie (1776-12-23). Original text: ‘ … tot heeden eenparig in den staat der slavernij binden’t geene de suptt. in zijne seele smettelijk komt te sijn … ’.

15. Dataset I.

16. NL-HaNa, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 415, scan nr. 25, folio nr. 23. Petitioner: de neger Quassi van Timotibo. Manumittee: Quassie (1775-12-19).

17. NL-HaNa, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 421, scan nr. 401, folio nr. 371. Petitioner: de vrije Betje van Pardo. Manumittee: Gratia (1779-02-19). NL-HaNa, RvP, inv. nr. 442, scan nr. 251, folio nr. 37. Petitioner: de vrije Catharina van Dikie Samson. Manumittee: Fenecia (1787-05-14).

18. NL-HaNa, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 417, scan nr. 93, folio nr. 44. Petitioner: Jan Willem Boom. Manumittee: Nanie (1776-12-23).

NL-HaNa, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 430, scan nr. 165, folio nr. 70. Petitioner: de vrije Cato van Vuist. Manumittee: Alida (1782-12-16).

19. NA, 1.05.10.02, inventory nrs: 394, 395, 396, 398, 400, 402, 405, 407, 423, 411, 417, 413, 415, 421, 424, 425, 430, 434, 436, 437, 442, 443, 446, 448, 449, 452, 453, 535, 458, 459 and 461. No notable change in distribution of certain bonds was found in the timeframe of 30 years.

20. NL-HaNa, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 415, scan nr. 25, folio nr. 23. Petitioner: de neger Quassi van Timotibo. Manumittee: Quassie (1775-12-19).

21. NL-HaNA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 458, scan nr. 133, folio nr. 16. Petitioner: de vrije mulattin Paulina van de weduwe Godefroij. Manumittee: Cato (1794-12-08).

Inv. nr. 452, scan nr. 71, folio nr. 23. Petitioner: De vrije Negerin Princes van Meel. Manumittee: Coba (1791-08-16).

Inv. nr. 535, scan nr. 35, folio nr. 9. Petitioner: de vrije Madras van Vogel. Manumittee: Louisa (1792-05-25).

Inv. nr. 398, scan nr. 523, folio nr. 527. Petitioner: J.J. Rouleau. Manumittee: Frenk (1767-08-10).

Inv. nr. 421, scan nr. 401, folio nr. 371. Petitioner: de vrije Betje van Pardo. Manumittee: Gratia (1779-02-19).

Inv. nr. 400, scan nr. 41, folio nr. 35. Petitioner: de vrije Neegerin Quasiba van wijlen de Loncour. Manumittee: Amimba (1768-05-10).

Inv. nr. 396, scan nr. 335, folio nr. 163. Petitioner: de vrije Angelica. Manumittee: Coffij (1766-05-21).

Inv. nr. 458, scan nr. 161, folio nr. 19. Petitioner: de vrije Diana van Adam. Manumittee: Adam (1794-12-19).

Inv. nr. 446, scan nr. 347, folio nr. 49. Petitioner: Affiba van Goede. Manumittee: David Nicolaas Goede (1789-08-17).

Inv. nr. 402, scan nr. 713, folio nr. 351. Petitioner: de vrije mulattin Bethie. Manumittee: Tobias (1769-08-14).

Inv. nr. 417, scan nr. 519, folio nr. 255. Petitioner: Jan Hendrik Samson. Manumittee: Kwauw/Quaauw (1774-04-21).

22. Smidt en Lee, Plakaten, ordonnantiën en andere wetten uitgevaardigd in Suriname, 1667–1816, 690. Number 573.

23. NL-HaNA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 417, scan nr. 519, folio nr. 255. Petitioner: Jan Hendrik Samson. Manumittee: Kwauw/Quaauw (1774-04-21).

NL-HaNA, inv. nr. 424, scan nr. 155, folio nr. 59. Petitioner: Samuel Townshend. Manumittee: Dorothea (1780-05-23).

NL-HaNA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 442, scan nr. 251, folio nr. 37. Petitioner: de vrije Catharina van Dikie Samson. Manumittee: Fenecia (1787-05-14).

NL-HaNA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 453, scan nr. 169, folio nr. 62. Petitioner: de vrije Dina van Stolting. Manumittee: Welkom (1791-12-06).

NL-HaNA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 461, scan nr. 323, folio nr. 40. Petitioner: de vrije Diana van Adam. Manumittee: Santje (1796-02-08).

24. NL-HaNA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 453, scan nr. 169, folio nr. 62. Petitioner: de vrije Dina van Stolting. Manumittee: Welkom (1791-12-06).

25. NL-HaNA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 439, scan nr. 89, folio nr. 22. Petitioner: J.D. Bartholomaij. Manumittee: Profit, Dirk, Dina, and Marianna (1786-05-26).

26. NL-HaNA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 424, scan nr. 155, folio nr. 59. Petitioner: Samuel Townshend. Manumittee: Dorothea (1780-05-23).

27. NL-HaNA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 424, scan nr. 155, folio nr. 59. Petitioner: Samuel Townshend. Manumittee: Dorothea (1780-05-23).

28. NL-HaNA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 413, scan nr. 917, folio nr. 482. Petitioner: de vrije negerin Catharina van Dikje Samson. Manumittee: Venus (1775-05-21).

29. Ibidem. Original text: ‘Egter al nu ontwaer komt te worden, hij daer van is afwijkende en gantschelijk met sijne dogter, niet en handelt soo als een vader betaemd te doen, alsoo hij buijten kennis en weeten van de supt. als moeder van voorn Venus weetende deselve met haar dogtertje op een clandestine wijze te koop presenteert aen particuliere lieden en ook daar omtrend eenige onderhandeling is maakenden. En dewijle diergelijke weederzegtelijks en ongepermitteerde menees sijn strijdende teegens de geusiteerden wetten, placaten en de natuurlijke pligten van ouders, ten opsigten hunne kinderen, ‘t gunt ook met eerbied gezegd ten hoogste corrigibel is’

30. NL-HaNA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 413, scan nr. 925, folio nr. 486. Petitioner: Barend Quassie den Loester. Manumittee: Venus (1775-05-21). All information on this case is based on this request. Original text: Off de negerin Venus een dogter van den berigter is (jaa dan neen), ’t contraer van dien word deeser seijds gesustineerd alsoo de handelingen van haar in geenen deelen over een komen (met soodaningen) als kinderen aan ouders verschuldigd zijn nogthans, ’t zij hoe het zij: genoeg is ’t dat den berigter ten evidenste met quitantie kan bewijzen haar te hebben gekocht; gelijk sulks bij requeste ook werd erkend’

31. Ibidem. Original text: ‘Wat het geposeerde aangaat; naamelijk dat den berigter bij’t aangaan der koop beloofd soude hebben; aan haar Venus, den schat den vrijheid te sullen schenken, doen ten deesen in geene deele tot de saak; aangesien ingevalle sulks de waarheijd was (en) hadde zij daar van willen profiteeren soo hadde zij zich een gansch andere levenswijse moeten voeren; maar geensints den berigter daagelijks het grootste verdriet aandoen, gelijk den berigter in waarheijd betuijgd; soo noopens haar lasteringe als noopens haar maandelijkse vastgestelde weeks off maands gelde; gerekend circa een jaaren daar aan niet te voldoen’

32. NL-HaNa, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 442, scan nr. 251, folio nr. 37. Petitioner: de vrije Catharina van Dikie Samson. Manumittee: Fenecia and Johanna (1787-05-14).

33. (Ben-Ur, 2015, p. 4) Complete quote: ‘Many of the cases here considered do point to emancipatory strategies, but others speak unmistakably to the key role of coercive economy in families emerging from enslavement. In both scenarios the agency of families follows the exploitative logic of a slave economy’.

34. NL-HaNA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 438, scan nr. 57, folio nr. 13. Petitioner: de vrije Dorsoe Vigiland. Manumittee: Diana (1786-02-13). NA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 458, scan nr. 161, folio nr. 19. Petitioner: de vrije Diana van Adam. Manumittee: Adam/Iszaak (1794-12-19).

35. NL-HaNA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 461, scan nr. 323, folio nr. 40. Petitioner: de vrije Diana van Adam. (1796-02-08).

36. This manumission takes place in 1796 and therefore the additional tax of 100ƒ also needs to be collected, on top of clerical costs.

37. NL-HaNA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 461, scan nr. 323, folio nr. 40. Petitioner: de vrije Diana van Adam. (1796-02-08).

Original tekst: ‘Haar suppliante [Diana] met Snoode ondank, Ja! Met disrespect en laage verachting bejeegend, in zoo verre, dat zij ondersteund door andere zig een geruijme tijd heeft onttrokken aan de slaafsche verplichting’

38. Ibidem.

39. NL-HaNA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 461, scan nr. 323, folio nr. 40. Petitioner: de vrije Diana van Adam. (1796-02-08).

40. NL-HaNa, Index Suriname: Gereformeerden (1.05.11.16), Doop-, trouw- en begrafenisregisters. (Index Reformed Church. Baptismal, marriage and burial records) Original source: Algemeen Rijksarchief Den Haag (ARA), Oud archief Burgerlijke Stand Suriname, inv.nr. 9, kerkboek 1688 – 1730 (Paramaribo) and inv. nr. 35, page 10. (Old Registry Office Archive Suriname, churchbook 1688–1730).

41. Jan Samson was a carpenter and made tent boats for a living, which was recognized as two separate trades.

42. ‘Jan Hendrik Samson’ in Scheepsregisters (Ship Registers), ‘NL-HaNA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 417, scan nr. 519, folio nr. 255. Petitioner: Jan Hendrik Samson. Manumittee: Kwauw/Quaauw (1774-04-21).

43. NL-HaNA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 417, scan nr. 563, folio nr. 232. Memorie by de vrije mulat Jan Samson on the request of Kwauw. (1777-05-15).

44. NA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 417, scan nr. 463, folio nr. 232. Petitioner: Dirck van der Mey. Manumittee: Dirk (1777-05- 15).

45. Patterson distinguishes seven types throughout the slaveholding world: post-mortem, cohabitation, adoption, political, collusive litigation, sacral and purely contractual.

References

- Ben-Ur, A. (2015). Relative property: Close-kin ownership in american slave societies. New West Indian Guide, 89(1–2), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1163/22134360-08901053

- Ben-Ur, A. (2020). Bound together?: Reassessing the “slave community” and “resistance” paradigms. Journal of Global Slavery, 3(3), 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1163/2405836X-00303001

- Blackburn, R. (2009). Introduction. In R. Brana-Shute & R. J. Sparks (Eds.), Paths to freedom (pp. 1–14). University of South Carolina Press.

- Brana-Shute, R. (1985). The manumission of slaves in Suriname, 1760-1828 [ Unpublished dissertation].

- Brana-Shute, R. (1989). Approaching freedom: The manumission of slaves in suriname, 1760-1828. Slavery & Abolition, 10(3), 40–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/01440398908574991

- Chira, A. (2018). Affective debts: Manumission by grace and the making of gradual emancipation laws in Cuba, 1817–68. Law and History Review, 36(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0738248017000529

- Dantas, M. L. (2008). Black townsmen: Urban slavery and freedom in the eighteenth-century Americans. Palgrave Macmillan.

- de, S., & van der Lee, T. (Eds.). (1973). Plakaten, ordonnantiën en andere wetten uitgevaardigd in Suriname, 1667-1816. (Placards, ordinances and other laws enacted in Suriname, 1667-1816). Amsterdam: Emmering, 1973.

- Ekama, K. (2020). Precarious freedom: Manumission in eighteenth-century Colombo. Journal of Social History, 54(1), 88–108. https://doi.org/10.1093/jsh/shaa008

- Fatah-Black, K. (2018). Eigendomsstrijd: De geschiedenis van slavernij en emancipatie in Suriname. (Battle for ownership: The history of slavery and emancipation in suriname). Ambo/Anthos.

- Fatah-Black, K. (2020). The use of wills in community formation by former slaves in Suriname, 1750-1775. Slavery & Abolition, 41(3), 623–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144039X.2019.1703511

- Hoefte, R. (2008). Free blacks and coloureds in plantation Suriname. Slavery & Abolition, 17(1), 102–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/01440399608575178

- Hove, O. T., & Hoogbergen, W. (2001). De vrije gekleurde en zwarte bevolking van Paramaribo, 1762-1863. The Free Coloured and Black Community of Paramaribo, 20(2), 306–320.

- Morgan, J. L. (2021). Reckoning with slavery: Gender, kinship, and capitalism in the early Black Atlantic. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478021452

- Mustakeem, S. M. (2016). Slavery at Sea: Terror, sex, and sickness in the middle passage. University of Illinois Press.

- Negrón, R. (2022). The ambiguity of freedom: Kinship and motivations for manumission in eighteenth-century suriname. Slavery & Abolition, 43(4), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144039X.2022.2061125

- Neslo, E. (2016). Een ongekende elite : de opkomst van een gekleurde elite in koloniaal Suriname 1800-1863 = An unprecedented elite : the rise of a coloured elite in colonial Suriname 1800-1863.

- Patterson, O. (1985). Slavery and social death: A comparative study. Harvard University Press.

- Patterson, O. (2017). Authority, Alienation, and Social Death. Critical Readings on Global Slavery, 90–146. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004346611_006

- Penningroth, D. C. (2003). The claims of kinfolk: African American property and community in the nineteenth-century South. University of North Carolina Press.

- Penningroth, D. C. (2007). The claims of slaves and ex-slaves to family and property: A transatlantic comparison. The American Historical Review, 112(4), 1039–1069. https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr.112.4.1039

- Vrij, J. J. (1998). Jan Elias van Onna en het ‘politiek systhema’ van de Surinaamse slaventijd, circa 1770-1820. (Jan Elias van Onna and the ‘political systhema’ of the Surinamese period of slavery, circa 1770-1820). Tijdschrift voor Surinaamse taalkunde, letterkunde en geschiedenis. OSO.