ABSTRACT

After World War II, socialist states developed a new schooling system aimed at building an egalitarian society. While there is a solid body of research discussing the relationship between the intent and effect of the egalitarian design of socialist school systems, the importance of school maturity assessments for the socialist project has received only minor attention. This article discusses how the introduction of school maturity assessments developed by experts in medicine, psychology, and pedagogy in 1960s Hungary and East Germany contributed to the visibility of children who were deemed immature. It shows that both socialist states developed institutional solutions beyond the standard school system for tackling the problem of school immaturity in children; these solutions, in turn, evoked different reactions from parents. As the article discusses, parents used various avenues to oppose the official expert assessments with which they disagreed. In both countries, parents increasingly voiced their opinions in complaint letters addressed to the state in a quest to overcome what they perceived as a severe threat to their children’s ‘normal’ development. By tracing parental bottom-up initiatives, the article investigates how parental agency ultimately shaped state policies and expertise despite the asymmetrical power relations that were present in these authoritarian societies. To show the interplay of parental agency, experts, and the state, we employ a combination of two methodological approaches, the sociology of expertise and the concept of Eigensinn, for understanding the spaces of negotiation and the role expertise plays in it. This article thereby sheds light on parental agency and its impact on expertise and state policies concerning school maturity in two socialist states that offered very different institutional answers to the problem; bureaucratic approaches towards complaint letters also varied significantly.

1. Introduction, methods, and sources

After World War II, socialist societies in East-Central Europe developed alternative models of schooling tailored to the building of an egalitarian society. A newly designed compulsory eight-year school system was aimed at expanding education for all and addressing the needs of those coming from previously disadvantaged backgrounds. In this context, experts identified a child’s sufficient physical, mental, and social development, or school maturity, as a necessary pre-condition for ensuring an equal start. In Hungary and East Germany, state institutions, based on expertise, introduced new methods for assessing school maturity with the objective of determining whether children were adequately developed to enrol in standard schools, which, implicitly and explicitly, constituted a school trajectory attributed to ‘normalcy’. However, the assessment of school maturity was often stringent, leading to the placement of children in special forms of educationFootnote1 under the presumption that school immaturity was a correctable condition. After the mid-1960s, there was a rising stigma associated with these education settings for the children insufficiently developed for entering school. This coincided with a surge in the number of children assessed as immature despite their parents’ belief that they were well suited for the ‘normal’ educational path. Consequently, dissatisfied parents began to voice complaints against both expert assessments and state schooling policies. The parents managed to bring the state’s attention to the issue of schooling practices, making it reconsider and, ultimately, change its schooling policies.

This text comparatively analyses the interplay between parental complaints, experts, and state policies in two East-Central European countries: Hungary and East Germany. Despite being socialist states, the solutions offered for managing school maturity issues varied greatly. However, despite their differences, Hungary and East Germany had a generalised institutional setting to educate immature children. In Hungary, ‘corrective classes’ were the most common option for school-immature children; these classes served as a temporary solution enabling children to catch up and re-enter standard school later.Footnote2 In East Germany, the ‘Sonderschule’, or special school, was the main and rather rigid option which, in most cases, prevented a return to a standard school trajectory. Given the stark differences in their management of school immaturity issues, the two countries offer a productive comparison revealing remarkable differences within the ‘socialist bloc’. We compare these two institutional settings as they were prominently discussed in expert writings, at the ministerial level, in the public sphere, and in parental complaints. Despite the differences between schooling practices for immature children in both countries, they equally provoked discontent in parents, who expressed similar anxieties that if their children were placed in a corrective class or a Sonderschule, they would never catch up with the parental understanding of ‘normalcy’. While both countries received a noticeable influx of complaints, Hungary’s complaint system was more decentralised than the highly institutionalised bureaucratic apparatus of East Germany; this offers another fruitful avenue for comparison (Grexa, Citation2023). By taking these different institutional arrangements into account, the article traces diverse forms of complaint and compares the extent to which parents were able to question school maturity assessments and schooling practices in Hungary and East Germany. Ultimately, we aim to provide a more complex understanding of governmentality in the authoritarian states of East-Central Europe beyond top-down governmental actions. We show that families, particularly parents, expressed concerns about the future development of their children, thereby initiating shifts in expertise and state policies.

In this text, we utilise the methodological tools of the sociology of expertise. As articulated by Gil Eyal, the production, reproduction, and dissemination of expertise is ensured by a network connecting ‘not only the putative experts but also actors, including clients and patients, devices and instruments, concepts, and institutional and spatial arrangements’ and shaping how a particular problem is approached. In a powerful attempt to explain the ‘social origins’ of a stark rise in autism diagnoses, Eyal included middle-class parents as influential actors who furthered expertise by becoming lay experts themselves. Eyal showed how the de-institutionalisation of mental retardation enabled parents to involve themselves as actors in the network, contributing to what came to be understood as an autism epidemic. As Eyal pointed out, ‘it was this new actor-network, composed of arrangements that blurred the boundaries between parents, researchers, therapists, and activists, that was finally able to “solve” the problem’ (Eyal, Citation2013). It is crucial to view expertise not solely as the perspective of professional experts but as the outcome of a network that also encompasses ordinary people, whose participation in a particular problem of expertise can trigger changes in the understanding of it. In fact, parents came to play a crucial role by challenging professional jurisdiction on autism and, by doing so, paving the way for the reconfiguration of the corresponding network of expertise (Eyal, Citation2013). In a similar vein, Steven Epstein observed how the response by patients to medical practices in the AIDS epidemic gave rise to an alternative ‘lay expertise’ that activists used to introduce decisive modifications to clinical trials. Epstein showed that lay approaches can eventually be integrated into established knowledge networks and influence official expert discourses and practices (Epstein, Citation1995), complementing or even overcoming the jurisdictional claims of professional experts. As our analysis shows, from the mid-1960s on, new screening methods made the problem of school maturity more visible and more discussed, provoking parental reactions aimed at overturning expert diagnoses. Eyal and Epstein have argued that lay experts are also part of expertise ‘networks’ and their endeavours contribute to shaping changes in expertise. However, as we show in the article, ‘lay people’ do not necessarily have to act as ‘lay experts’ to trigger changes in expertise. Most of the Hungarian and East German parents we analysed did not conceive themselves as such, nor did they usually educate themselves on the expertise of the issue at stake. Instead, they complained individually based on their lay observations while pursuing what they thought was best for their children. But, similarly to Eyal’s examples, this was done to such a broad extent that parents were able to condition expertise and, above all, to influence state education policies.

This addition to the sociology of expertise brings to the forefront the role of ordinary individuals, particularly parents, in their interaction with experts and the state – a relationship often referred to as ‘agency’. However, our understanding of agency goes beyond recognising individual resilience as merely a form of resistance to power. Recent perspectives have raised concerns about simplistic views of agency, viewing it as a conceptual tool that serves both as the ‘starting point and concluding argument’. In essence, it is seen as a celebratory term that honours individuals but lacks the explanatory depth to uncover power dynamics (Thomas, Citation2016). The main issue lies in how agency is frequently portrayed as ‘undifferentiated’ and, significantly, as a ‘binary’ concept that artificially separates individuals from power (Gleason, Citation2016).

While we continue to use the term agency, our primary conceptual framework applies the concept of Eigensinn (self-will or obstinacy); utilising this framework helps overcome some of the conceptual traps to better frame ‘parental agency’ and its interactions with experts and the state. Eigensinn, developed by German historians of everyday life and often kept in German due to its nuanced complexity, conveys the capacity for individuals to reappropriate their environment and construct their own space. It does not foreground an unfettered agency but rather situates individual strategies in the context of the ‘social praxis’ of power dynamics, which are more playful and less binary than some simplistic usages of agency often assume (Lüdtke, Citation1991, pp. 9–63). There is no such thing as a state that sanctions policies and conditions expertise, and a society of individuals that follows the norms imposed top-down. Rather, the borders are blurry; even in authoritarian systems, there are spaces of negotiation, with shared forms of communication in which the exchanges are decisive for comprehending the functioning of state and society. To address parental complaints that were explicitly not based on expert knowledge, we complement the sociology of expertise with the concept of Eigensinn. This helps us to adequately frame the parental reasoning and the significance of their actions by tracing the meaning they attributed to the issues at stake (Lindenberger, Citation1999). The Eigensinn concept highlights how individuals reproduced the language of the state with the goal of exerting pressure on institutions and getting something in return. In this text, we show how parents ‘took the word’ to the state and experts; that is, they often appealed to state institutions with the aim of overturning individual cases in which children were diagnosed as inadequately developed for school. These complaints eventually triggered a change in the general assessments of school maturity and schooling practices (Straughn, Citation2005).

Our approach combines the tool of the sociology of expertise as developed by Eyal with the methodological tool of Eigensinn; we aim to analyse the motivations of parents and scrutinise the power relation between the state and parents in socialist societies that was relevant for the development of expertise. By combining these two methodological approaches, we are aiming to integrate the state as an identifiable actor in networks of expertise, geared towards the state-socialist context or, more generally, authoritarian societies. While Eyal’s definition of a network of expertise does not exclude state actors per se, we do not think that the possible influence of state actors nor the power relations between the state and experts and between the state and lay experts have yet been sufficiently brought into focus. We therefore seek to complement Eyal’s exploration of power relations among experts and between experts and lay experts in their struggle over jurisdiction, as coined by Abbott, with the asymmetrical relationship of power between the state and citizens and its impact on the formation of networks of expertise. The Eigensinn concept helps us to show some of the motivation experienced by parents to involve themselves in the discussions on school maturity issues, potentially making an impact on networks of expertise. By exploring the still understudied factor of parental motivation, we shed more light on the complexities of the conditions necessary for a specific network of expertise to evolve and, thereby, hope to advance our understanding of expertise more generally.

To analyse the topic, we relied on a vast array of sources. We used published sources such as the official press and expert literature in which experts expressed not only their understanding of school maturity, but their implicit conception of what ‘normalcy’ meant in relation to schooling practices. We also used archival material from educational institutions, ranging from local authorities to the ministry, to help us reconstruct the lines of communication between experts, the state, and parents. We utilised a broad range of parental letters that demonstrated how parents complained and how these complaints were handled by the official institutions. In this type of source, the East German Eingaben (petition) system stands out as a central and specific institution. This system entailed an official procedure that allowed citizens to submit written petitions to the state with the aim of resolving issues or seeking compensation for perceived grievances. In the 1970s, the Eingaben system saw a significant increase in the number of petitions, marking the emergence of a ‘culture of complaint’ in East Germany (Betts, Citation2010). We argue that the thoroughness and the centralisation of the Eingaben system conditioned the state responses and made the ministry side with the parents, overruling experts. In Hungary, there was not such a centralised institution for citizen complaints; however, in their search for a solution to their problems, ordinary people addressed their grievances to respective ministries, trade unions, and state media outlets, resulting in a scattered landscape of complaints (Grexa, Citation2023; Ispán, Citation2019). For this article, we analysed parental letters from the 1970s directed to the panasziroda (office of complaints) at the Hungarian Ministry of Education.Footnote3 For the 1980s, we show how complaints were specifically impactful in East Germany, coinciding with the late socialist context in which the states weakened, granting individuals greater leeway (Winkler, Citation2023). There were still some differences. The East German state maintained some strength while party structures weakened (Pannen, Citation2018). Hungary, on the other hand, experienced a noticeable state in retreat; this was reflected in liberalisation tendencies in the education system, particularly in the latter half of the 1980s (Baár, Citation2015; Melegh, Citation2011; Millei & Imre, Citation2013; Mincu, Citation2016).

Scholarship has shown how the socialist takeover in East Germany rapidly introduced changes in a newly constructed education system (Rodden, Citation2002). Early childhood education became a cornerstone of the whole system and school maturity assessments commenced in kindergarten (Konrad, Citation2015). The ideological Cold War German-German competition led the GDR to design a strict system for admission to standard school that excluded many children who were deemed immature (Schmidt, Citation1996); this was done to achieve the low school failure statistics that the GDR wanted to showcase (Geiling, Citation1999). Scholarship has also analysed the admission procedure to schools for immature children, pointing out the opacity of the process and how being assigned to a special school was usually a dead end that hindered children in their development and provoked parental discontent (Floth et al., Citation2022; Vogt, Citation2021). The extent to which that parental discontent influenced changes in the special schooling system has thus far received little attention. Other bodies of scholarship have looked into how parental agency contributed to shaping GDR family policies (Harsch, Citation2007; Meyer, Citation1992). As we show, parental agency also effectively shaped the schooling policy for immature children.

In Hungary, general school education was seen as a powerful tool for doing away with previous class divisions and paving the way for social equality. Additionally, the turn to industrialisation and the modernist project more generally required a well-trained and skilled workforce, and a growing bureaucracy needed educated cadres sympathetic to the socialist project. However, increasing scholarship has questioned whether equality was successfully created through the socialist school system (Hanley & McKeever, Citation1997; Millei et al., Citation2018). Building upon this line of thought, this text engages with the problem of school maturity, which has thus far rarely been a topic of historical inquiry.Footnote4 New research, however, has approached the subject of school maturity in the socialist context.Footnote5 The return of psychology as an independent discipline at research institutions and universities during the process of de-Stalinisation had a decisive impact on how practices regarding the screening and treatment of school immaturity developed (Kovai, Citation2016; Lászlófi, Citation2019; Máriási, Citation2019; Pléh, Citation2016; Szokolszky, Citation2016). A solid body of scholarship has been engaged with the relationship between psychology and education in socialist Hungary, identifying the 1960s as a decade of heightened collaboration between the two disciplines (Darvai, Citation2019; Kovai, Citation2019; Laine-Frigren, Citation2019; Sáska, Citation2020). While we show that the question of ethnicity mattered in Hungary, recent research more systematically explored the precarious situation of Roma children within the Hungarian school system (Géczi, Citation2012; Varsa, Citation2017). The 1980s in Hungary were a period of substantial change in all spheres of life, and the education system was no exception. Decentralisation and austerity measures also affected schooling practices for the last decade of state socialism, as Melinda Kovai and Eszter Neumann convincingly showed as they explored the egalitarian efforts of the socialist state and its demise in detail (Kovai & Neumann, Citation2015).

2. Schooling immature children: state solutions for a rising problem

In East Germany, the socialist model pursued an education system that significantly addressed social class disparities and aimed at achieving equality. The Ministry of Education initiated a comprehensive approach to monitoring children’s development, commencing with their enrolment in kindergarten.Footnote6 Consequently, the process of assessing school maturity started during kindergarten attendance. Teachers assumed the responsibility of meticulously documenting and analysing the evolution of each child’s development. In practice, their task was to identify any issues that might hinder a child’s maturity and subsequent integration into the standard school system. These criteria remained relatively consistent over time in East Germany. As evidenced by a report from the National Education Ministry in the 1960s, the prevailing approach was that ‘the child should learn at an early age to live in a group of peers and to feel comfortable in joint activities with others’. This approach underscored the enduring emphasis on social integration and collective engagement as fundamental indicators of a child’s maturity for standard education within the East German socialist model.Footnote7

In the education system, the guidance of expert pedagogues was pivotal in shaping the criteria by which teachers evaluated children. East German pedagogues trusted their capacity to help children acquire maturity through their intervention, be it advice to parents, guided activities, or follow-up examinations.Footnote8 Consequently, East German pedagogues directed their efforts towards assessing children with a focus on identifying deficiencies, particularly in terms of adaptability to the group. This approach often resulted in a high number of children being categorised as immature. However, being deemed immature did not imply disability or the inability to receive an education. In the 1950s, East Germany had established state-led educational programmes designed to address, amongst other conditions, the needs of these immature children, notably the Sonderschule.Footnote9 These were established to accommodate children with slower developmental progress who were assessed as ‘bildungsfähig’ (educable), including those with speech impairments, deafness, blindness, and delayed development. Though not included in the regulations, in practice, children with perceived ‘behavioural problems’, often from disadvantaged backgrounds, were also directed to these schools (Geiling, Citation1999, pp. 169–172). These elements fostered a perception that Sonderschulen typically enrolled children deemed as abnormal or troublesome, leading to frustration among parents who saw their children as normal and, consequently, expected them to attend a standard school (Floth et al., Citation2022).

East German experts conceived Sonderschulen as an alternative approach to education, aimed at supporting children with special needs. A significant distinction existed between these children and severely impaired children who were ‘bildungsunfähig’ (uneducable) and were instead cared for in daycare centres under the supervision of the Ministry of Health. The Sonderschule was designed to help educable children to pursue a conventional career path, including the option to complete Abitur (secondary school), which allowed for tertiary education. In theory, if children attending a Sonderschule overcame their developmental delay swiftly, they could be transferred to a standard school. However, this transition occurred infrequently, and most children enrolled in a Sonderschule remained there (Baudisch, Citation1993).

In the late 1960s, inspired by pedagogues, the Ministry of Health introduced school maturity tests, aiming to provide a more precise assessment of school maturity; this led to an increase in the number of children identified as immature. Simultaneously, kindergarten teachers retained their influential role in evaluating school maturity. This approach aligned with broader state policies during the competitive climate of the Cold War. The East German state was determined not to fall behind West Germany in terms of school failure statistics, prompting kindergarten teachers to maintain strict standards, ensuring that only fully mature children advanced to standard schools (Schmidt, Citation1996). This rigorous approach by kindergarten teachers created dissent among some pedagogues, who criticised those teachers who ‘are of the opinion that our socialist school is more difficult than the previous [not socialist] one’ and therefore viewed any hint of developmental delay as school immaturity.Footnote10 The increasing number of immature children sent to a Sonderschule caught the attention of the Ministry of Education, who started to notice a rising problem: ‘The present situation in this area is very unsatisfactory and the constant and justified complaints on the part of the parents cause considerable difficulties for the competent authorities.’Footnote11

Parental outrage was further intensified by two additional factors. First, throughout the entire socialist period, there was a noticeable ‘border area’ without clear distinctions between mature and immature children (Vogt, Citation2021). Parents perceived a lack of clear guidelines and a sense of randomness in the decisions made regarding their children’s education. Second, in the early 1970s, a reform of the Sonderschule was implemented. From that moment on, children who did not display signs of developmental progress within the first two years could also be transferred to daycare centres for uneducable children (Geiling, Citation1999). Consequently, the stigma associated with Sonderschulen continued to grow; by the early 1970s, parents were increasingly voicing their complaints through the official Eingaben system.

By the end of the 1950s, Hungarian experts were equally alarmed by rising school immaturity levels, preventing children from having an equal start at school and therefore endangering state efforts to overcome previous class divisions. According to expert estimates, eight to ten percent of the first graders were not yet mature enough to enter school, showing ‘unstable attention, possible speech deficits […], emotional underdevelopment and consequent infantile behaviour, increased mobility, lack of work maturity, lack of task awareness’ (Szabó, Citation1969). Once immature children started school too early, according to the experts, they were in danger of falling behind due to the overload they experienced, which negatively affected both their psychological state and their future school trajectory (Szabó, Citation1969). While experts consistently stressed that school immaturity was not a disability but a retardation, meaning a delay in the child’s physical and mental development, it required the attention of a broad range of experts, such as medical doctors, pedagogues, and psychologists, to assess the condition reliably. Indeed, the involved disciplines relied heavily on each other. The post-1956 return of psychology to research institutes and universities contributed decisively towards the development of reliable screening techniques (Kovai, Citation2016; Lászlófi, Citation2019; Máriási, Citation2019; Pléh, Citation2016; Szokolszky, Citation2016).

Heightened discussions in expert circles made their way to the governmental level. As a result, the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Education settled on a new school enrolment system in 1964. Based on expert advice, they introduced a compulsory examination with the school paediatrician for children of pre-school age as a necessary precondition for entering school. As psychologists were not yet available in sufficient numbers, they would only engage in a more complex examination of the child after the paediatrician detected borderline cases via a basic standardised psychological screening. Once a child was assessed as immature, the only option experts could offer to parents was to delay school entry by one year. This option was highly unpopular with parents who considered it a disgrace if the child was not enrolled on time; this perception was also led by the widespread understanding that the child would ‘lose’ a year (G. Horányi, Citation1966). Experts, by contrast, voiced their concerns that school-immature children – who in more than half of the cases experienced these conditions due to the environment they were growing up in – were left to their fate without adequate support, especially when the children did not attend kindergarten at pre-school age (Szabó, Citation1967).

It was exactly this worry that prompted experts and state officials to start a pilot project in the capital, introducing small ‘kísérleti osztályok’ (pilot classes) with a maximum of 15 children instead of the usual 30 to 40, allowing the responsible teachers to devote tailored attention to every child (Szabó, Citation1967). As they ran parallel to existing classes in elementary school, children who caught up could switch into standard classes later without ‘losing’ a year before entering school (Szabó, Citation1969). Responding to the positive dynamics, the Ministry of Education ordered by decree the possibility for elementary schools in Budapest to open such classes from the 1970/71 school year, now under the name of ‘korrekciós osztályok’ (corrective classes). The number of these classes rose dramatically in Budapest and a few years later also outside the capital city. By the beginning of the 1980s, 321 corrective classes were functioning throughout Hungary. Parallel to these developments, the introduction of a so-called complex enrolment examination, introduced in 1971, strengthened psychological and pedagogical expertise for the assessment of school maturity.

While the system for immature children in Hungary had a clearer ‘temporary’ dimension than the one in East Germany, where the Sonderschule was often a dead end to a child’s school trajectory, parents in both countries voiced similar disagreement vis-a-vis the authorities, often with the help of complaint letters. In the GDR, a rigid and ostracising system of auxiliary schools took care of school-immature children, provoking substantial protest in parents; Hungarian parents felt at least uncomfortable about an experimental, yet separate institution that marked their child as different but had an inbuilt upward mobility by making provisions to transfer. The following section more closely interrogates how German and Hungarian parents’ practices challenged procedures on the ground and exercised influence on state policies, focused particularly on the role of parental agency.

3. Parents vis-à-vis the state and the experts

3.1. Far from ‘normalcy’: the stigma of being school immature

In a report by the East German Ministry of Education from the mid-1970s, ministry officials were concerned about the increasing complaints showing ‘the doubts of parents who state clearly that they see the admission of their children to the Sonderschule as a restriction of the child’s opportunities for development.’Footnote12 Parents reasonably feared that if their children were placed in a Sonderschule they would never return to a standard school trajectory. Experts had fuelled the impression that schools other than standard schools were deviations from the norm. In 1967, a pedagogue wondered if ‘we should not raise the standards for the children’s admission to school’ and stated that ‘every normally developed, healthy child can reach the goal of the first grade’.Footnote13 Similarly, Klaus Rebelsky, who was a pedagogue and a member of the Ministry of Education, responded to the parental question of ‘who decides when a child is school mature?’ by supporting the state procedure and affirming that it guaranteed admission to standard school to ‘normally developed children who have the physical and mental prerequisites for the new stage of life.’Footnote14

East German children who were put in a Sonderschule deviated from the norm that experts delineated. This can be perceived in the proliferation of parental complaints in the 1970s and 1980s both in state media and in the Eingaben to the Ministry. In a letter to one of the most circulated daily papers, the Berliner Zeitung, a couple expressed that ‘a few weeks ago we were informed that [our daughter] might have to go to a Sonderschule’. They proposed instead: ‘Wouldn’t it be better to first enroll her in a normal school and then postpone the decision?’Footnote15 Other parents wrote: ‘We would like to point out that if the child does not reach his school goal, he may suffer (…) depressive behavioural disorders.’Footnote16 Parents thought that a child could only ‘develop optimally’ by being in a standard school and they therefore attempted to challenge their children’s placement in a Sonderschule, driven by the desire ‘to prove to our children and to ourselves that all decisions are just’, as a 1980 letter put it.Footnote17 One father justified his pursuit of normal school enrolment for his child as being ‘in the interest of our socialist state’ as the proper development of individuals was a concern not limited to families but also extending to the state level.

In East Germany, the stigma associated with being deemed immature for standard school was pervasive and, at times, even severe. Since the 1950s, experts had sought to determine the factors leading to youth criminality. A report published in the widely read Neue Zeit stated that ‘out of every ten youth criminals, about seven or eight did not complete primary school or only attended a Sonderschule’.Footnote18 This report was the first to draw a connection between school failure or the attendance of a Sonderschule and youth criminality rates. In the mid-1970s, when East German youth criminology gained prominence (Bratke, Citation1999), a study established a correlation between ‘school failure’ and criminal behaviour, highlighting that ‘50% of adolescent delinquents had not completed the 8th grade’ (Rydzynski, Citation1977). Even though Sonderschulen allowed children to complete their studies, some parents were apprehensive that attending such schools increased the likelihood of academic failure, which might then lead to criminality. In a 1982 study on youth criminality, the prominent psychiatrist Hans Szewczyk analysed the causes of criminal behaviour and found that ‘15% of the studied criminals had attended a Sonderschule’ (Szewczyk, Citation1982).

Although the findings did not support a strong correlation between school type and deviant life trajectories, the image of Sonderschulen as a potential cause lingered and parents still interpreted it as such. In one 1980 letter, parents who had realised that their child was going to be put in a Sonderschule, stated, ‘if Thilo was to be confronted with the criminal justice system, we would be held primarily responsible for his development’.Footnote19 Such parental letters aiming at overturning the decision of their children’s placement at a Sonderschule sometimes used what might have been exaggerations to pursue their goals. Nevertheless, the letters clearly show how parents drew upon an extensive societal concern regarding the outcomes of not attending standard school, a concern that was, in part, exacerbated by expert analysis and discourse.

In Hungarian society, the issue of school maturity was similarly widely discussed and received heightened attention through the spread of corrective classes from the 1970s onwards. Although part of the eight-year elementary school, the general opinion still perceived the corrective classes as a deviation from a ‘normal’ school trajectory (G. Horányi, Citation1966). In response to this perception, also due to judgmental social surroundings, many parents decided to challenge the decision by seeking an alternative assessment that would declare the child mature enough to enter first grade at six years. Even when corrective classes were within reach, many parents ‘feared that they [corrective classes] would not ensure the same knowledge and credentials as large [standard] classes’ (Szabó, Citation1969). Pedagogues needed to engage in intensive communication with the parents to convince them of the advantages of corrective classes, battling with what parents considered a ‘normal’ school trajectory. Many parents still did not follow expert recommendations as they saw ‘some kind of “stigma” or disadvantage in enrolling their child in a small [corrective] class’ (Szabó, Citation1970). Although the institutional arrangement aimed at the wellbeing and optimal development of the child, parental practices were to question or even contradict expert assessments, often in opposition to their child’s own interests (Faragó, Citation1966).

Since efforts to increase parental acceptance of corrective classes were not smooth, experts identified a need for heightened communication via state media outlets. As an article in the well-circulated newspaper Esti Hírlap in 1970 shows, public discourse aimed at normalising different developmental paces and collectivised efforts towards individual needs in children when saying that

the main goal is to help children to catch up as quickly as possible in small classes, to become ‘ready for school’, and to return to standard classes. Everyone is working on this: teachers, doctors, speech therapists, and psychologists, and that is why parents need to be more involved in their child’s schoolwork and thus in his or her development. Don’t be alarmed if your little one is placed in such a preparatory group; the rate of development is very differentiated.Footnote20

By normalising different paces of development, the article was trying to do away with the widespread understanding that children attending corrective classes were second-class students and artificially segregated from their peers. Indeed, catching up with peers attending standard classes was a central aspect of expert-sanctioned practices towards ‘normalcy.’

During the 1970s, numerous complaint letters from Hungarian parents to the Ministry of Education expressed conflicting understandings of ‘normalcy’ when pedagogues kept the children in special classes despite their potential to transfer back into the standard school system. All the letters concerned children who attended small classes in special schools, most possibly because corrective classes were not available nearby. In these instances, parents assessed how their child was catching up and requested placement in a standard school class. One of the parents, a father from a rural area close to the Slovenian border whose son attended the first two grades in a special school and was allowed to switch to elementary school by repeating the second grade, complained to the Ministry of Education: ‘Our son has now already lost two years of his life because of poorly presented facts, and if his teacher let him pass he […] would make progress in becoming an independent valuable worker of our country as soon as possible.’Footnote21 State officials, however, expressed a more relaxed approach towards different paces of development, advising the father to ‘calm down because the little boy struggled with major problems: Now one should be happy that he overcame them, that he will continue to be a regular student in an elementary school like the other children and that he will not have any problems in further education.’Footnote22 As this conversation shows, notions of normalcy could differ and come into conflict in the interaction between parents and ministerial experts.

However, other instances were not about the parental fear of their children not fitting in but rather about parental concern that their children would receive suitable treatment and schooling to develop as ‘normally’ as possible and, ideally, catch up. In such cases, parents considered the structured support, such as in special schools and corrective classes, lacking when they thought it was what their children urgently needed. In 1975, a mother from Tatabánya turned to the Ministry of Education after the school entry of her son had already been postponed twice because of a severe speech and hearing impediment. Fearing her son would not start any school, even for a third year, the mother finally received an answer that a pedagogical assessment would decide if the local elementary or the special school further away would be the best choice.Footnote23 The revealed parental understanding in these situations came the closest to experts’ notions of ‘normalcy,’ which considered the special institutions a vehicle, not an obstacle to normal development.

At the beginning of the 1970s, only a few years into the existence of corrective classes, experts started to investigate the social composition of these classes. After the local government of Budapest, based on experts’ proposals, introduced corrective classes as a pilot project, one of the major appeals lay in the social mobility even for children from problematic family backgrounds, prompting experts to praise corrective classes for their ‘equalising effect’ (Szabó, Citation1974). Although school maturity issues occurred disproportionally in lower-educated families, school-immature children were found across all the different strata (Szabó, Citation1969). However, expert studies on the social composition of corrective classes showed that children from the managerial and high-ranking intellectual elite were absent. In contrast, children of white-collar workers, production supervisors, and skilled workers were overrepresented. Even more strikingly, children of unskilled workers were underrepresented in corrective classes and overrepresented in special schools. Considering these results, the authors noted that ‘social factors other than “biological” factors play a significant role in determining who “meets” the requirements of primary school’ (Szabó, Citation1970), making the case that the social background of the family had an influence on whether an insufficiently developed child attended corrective class or standard school.

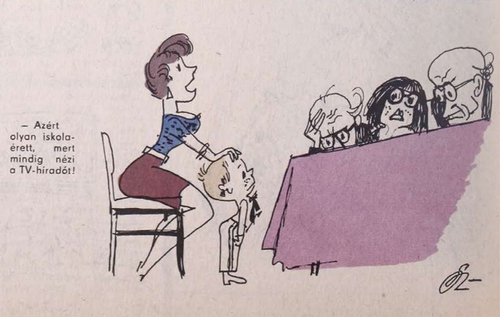

Indeed, as a caricature in the satirical magazine Ludas Matyi depicted, there was a public notion of well-to-do parents being instrumental in preparing their children for entering the standard elementary school system. The drawing showed an elegant, middle-class mother with her son in front of the Committee of the Educational Guidance Centre claiming that ‘he is so school mature because he always watches the news broadcasts on TV’. Her son had been trained to appear more like an adult than a child, with tidy and formal clothes and smart posture; the Committee was irritated and close to despair about the popular misunderstanding of what school maturity was about.Footnote24 The caricature reveals the aspirations of an affluent and educated stratum in Hungarian society as well as popular notions of school maturity, which were not necessarily in line with expert understanding.

‘He is so school mature because he always watches the news broadcasts on TV’ (Ludas Matyi 23 August 1984).

Social differences played out further in the uneven distribution of corrective classes in Budapest. Most of the corrective classes were in Districts III, X, and XV; the traditionally bourgeois Districts I and II had a high proportion of academically educated inhabitants and offered the fewest corrective classes. Even after a certain normalisation of corrective classes, District I’s Educational Guidance Centre reported at the beginning of the 1980s on how parents opposed the results of school maturity assessments and found ways to circumvent the recommendation. Other experts wrote about their experiences in District II, where the parents felt the stigma of corrective classes more intensively. In this vein, a complaint letter by a father from District II expressed his worries to the Ministry of Education that his son needed to repeat the first grade and that ‘teachers are about to disappoint him in his blossoming inner world, […] for him to probably experience the biggest disappointment of his life.’Footnote25 Since the Ministry of Education could not give a final decision on the repetition of the school year, it also stressed the school director’s sorrow that the original recommendation for corrective class had not fallen on fertile soil with the parents. In another instance, a father of six in rural Hungary protested against placing his son into a special school that was so far away that the child would have needed to stay in a children’s home. While the father did not oppose the special school, he fought the son’s separation from the family. However, he was convinced that ‘if someone of more reputable local standing had a child of perhaps more modest intellectual ability, they would certainly not be ordered to attend a special school. But it seems that there is still inequality between people and people […]’,Footnote26 making the point that the parent’s social capital mattered for the child’s school placement.

Roma children were diagnosed with signs of school immaturity more often than the rest of the population. Experts identified insufficient command of the Hungarian language, recurring respiratory illnesses due to substandard housing, and low intellectual stimulation at home as significant factors for higher immaturity rates.Footnote27 Experts welcomed complex school maturity examinations to assess school immaturity more reliably in Roma children, avoiding their placement in special school when they mostly suffered from temporary retardation instead of physical or mental disability.Footnote28 Since Roma children entered elementary school via corrective classes in greater numbers, many Hungarians attributed an even greater stigma to corrective classes. A grandmother from Sálgotorján, mainly responsible for the upbringing of her grandchildren after the recent death of their father, complained bitterly to the Ministry of Education about the school maturity screening where, except for her granddaughter, ‘only Roma children were found at the psychologist’. While the grandmother was of the stern opinion that ‘a psychologist destroys the child’, she also expressed the view that the need for psychological screening must have been down to the arbitrary judgment of the Educational Guidance Centre, even more so since there was ‘no father anymore to put his foot down’. Since the grandmother’s aversion to corrective classes was so strong, the psychologist advised placing the granddaughter in a standard class with additional tutoring,Footnote29 prioritising the delicate psychological state of the child after the father’s death. This serves yet as another example of how parental practices and eigensinnige complaints implicitly questioned the egalitarian idea of corrective classes, even more so when, for many, the attendance of Roma children increased their stigma.

3.2. Experts or parents: who is responsible for immaturity in children?

Parents often rejected experts’ school maturity assessments and state alternative schooling policies as inadequate for their children. In turn, experts tended to highlight that parents were to blame as they often did not provide a sufficiently stimulating family environment for the child to mature. There were remarkable differences in this between Hungary and East Germany.

In Hungary, experts understood parents to be decisive for a child’s environment, contributing to developmental delays in more than half of school-immature children. According to expert discourse in public media, it mattered how much time parents spent with their children and how they used the time to provide sufficient intellectual stimulation (Hamar, Citation1980). Many experts identified broken families, alcoholism, overstrained mothers, illiteracy, and low demand for culture as major negative factors.Footnote30 A neurologist at an Educational Guidance Centre in Budapest made an even more dramatic connection between a school-immature child and its parents who ‘are all seeing a neurologist or should at least do so’,Footnote31 declaring the psychological instability of parents ultimately responsible for the state of their children. Although kindergarten attendance could compensate for insufficient stimulation and stability at home, the discourse in public media pointed to parental involvement in school homework directly affecting the child’s development. The complaint letter of one divorced mother claimed that the father had manipulated a psychologist to issue a school immaturity assessment. According to the mother, this was happening to her ‘healthy, sane, intelligent child, with above average abilities’ to give the father ‘proof that the child is not developing properly under my care, and this would allow him to take the child away, which would also end his unpleasant obligation to pay child support.’Footnote32 While we cannot ascertain whether the mother was presenting the facts accurately, this case shows clearly how popular opinion related school maturity levels directly to proper parenting.

In the early 1980s, Hungarian experts and state officials noticed growing levels of school-immature children across the country. Although differences between counties were stark, rising alcoholism and increasing divorce rates took a toll on children, negatively affecting their maturity levels (Kerekes, Citation1985). The literature magazine Élet és Irodalom pointed to specific Hungarian conditions where a legalised second economy was blossoming, especially since the beginning of the 1980s, leaving parents with insufficient time to engage with their children (Albert, Citation1981). A school doctor in Budapest noticed the effects of the changing economic opportunities that 75% of all Hungarian families took advantage of, often with the mere aim of stabilising the family budget in the face of dramatic inflation rates. As the school doctor said in an interview, increasingly more children ‘do not know their colours, they do not know their address, let alone their mother’s name’. Furthermore, these children often came from economically comfortable backgrounds but lacked parental attention and stimulation (Nógrádi Tóth, Citation1985). The changing societal and political landscape created a burden for future Hungarian schoolchildren for whom the lack of parental attention became decisive in their development.

In East Germany, experts did not blame parents in public sources but instead addressed their criticism internally to the Ministry of Education. By the end of the 1970s, there was a clash of competencies: parents accused teachers and experts, and these, in turn, pointed out how insufficiently informed parents were for either providing a good environment for acquiring maturity, or being capable of assessing whether their children were ready to attend standard school. In an expert report sent to the Ministry in the 1970s, pedagogues particularly identified the problem in mothers who ‘have few professional qualifications, are often single, and more often have several children and, in some cases, are heavily burdened by work’. In these cases, their children ‘are still severely disadvantaged in their development and need special support’ and, furthermore, their assessments of the mother’s children’s maturity ‘are not always reliable’. Therefore, the report called for stronger pedagogical interventions at the expense of parental wishes.Footnote33

In parallel, the dynamic unleashed by the changes in the processing of Eingaben in the mid-1970s fostered an increase in parental complaints that hold views opposing those of the experts. The East German ministry registered a high number of parental complaints expressing profound ‘criticism or lack of understanding of decisions made by school officials and Sonderschulen teachers regarding the future development of their children.’ The Eingaben system, which was designed to address individual concerns, allowed for open criticism of various aspects of the socialist system. Nevertheless, these critiques predominantly pertained to specific issues (Bruns, Citation2016). Parents often blamed local authorities and directed their anger at schoolteachers, for instance alluding to the ‘intransigence of one individual’. Guided by the stigma associated with the Sonderschule, parents went on to blame the decision-making in the admission procedure and aimed to overturn it. ‘As parents, we are very bitter about the fact that we are not allowed to make a decision about our son,’ one Eingabe revealed.Footnote34 Another put it: ‘For our family, it is incomprehensible how a socialist leader in a conversation of 90 minutes […] does not show the slightest willingness to at least reconsider the decision.’Footnote35 They all formulated their complaints in a very similar manner, which might indicate that there was an exchange of experiences where parents informed each other how to effectively complain to the ministry to get something in return, that is, to get their children put in standard school.

As a result of the mutual accusations between parents and pedagogues, the ministry was somewhat forced to take sides. Disregarding expert reports blaming parents, a 1979 ministry report stated that ‘it becomes clear that education decisions which are necessary for school policy and are in the interest of the children are not explained to the parents in a long-term, trusting, convincing and comprehensive manner’ and proposed ‘to deal with the bureaucratic and heartless behaviour of individual employees towards citizens.’Footnote36 In another report from the following year, the ministry blamed pedagogues who were unable to handle parental anxieties and failed to ‘discuss the questions of their child’s admission to the Sonderschule’.Footnote37

In Hungary, an expert public discourse attributed deficiencies in child maturity to parental shortcomings. In stark contrast, the situation in East Germany was characterised by a substantial volume of centralised complaints that conveyed the impression to the Ministry of Education that parental discontent was pervasive. Experts in East Germany refrained from publicly assigning blame to parents. Even when such attributions were communicated through internal ministerial procedures, the ministry ultimately aligned itself with the parental perspective. The next section elucidates how the distinctive complaint procedures in Hungary and in East Germany triggered disparate responses from both experts and the state.

4. State reactions, expert responses, and policy changes during the 1980s

Expert interactions with parents changed over time, and parental reactions shaped experts’ public discourse on schooling for immature children. In East Germany, experts played a dual role: they contributed to the existing stigma associated with being labelled as a school-immature child and sent to a Sonderschule, but they also made efforts to counteract this stigma. Having acknowledged this pervasive prejudice against Sonderschulen, in the late 1970s and across the 1980s, experts attempted to publicly address these concerns to alleviate parental anxieties. In 1977, the East German TV programme ‘Elternsprechstunde’ (‘Parent’s Consultation Hour’), devoted an episode to: ‘Who goes to Sonderschule?’ In this episode, a pedagogue explained to the audience why attending such a school should not carry a stigma.Footnote38 In the widely read newspaper Berliner Zeitung, Wolfgang Sieler, renowned for his popular books on pedagogy, addressed the topic in a similar vein, offering guidance to parents on child-rearing and education (Sieler, Citation1984). Sieler responded to the pressing question: ‘Will our child be able to attend school?’ by remarking that ‘it is not a family flaw or a life tragedy if a child has to attend a Sonderschule.’ He also directed some remarks towards those who unfairly stigmatised children who did not conform to the norm, stating, ‘not everyone understands how to respond to the idiosyncrasies in the thinking and behaviour of these children (…) If ignorance leads to understanding, it may be forgivable; however, if arrogance and indifference foster an attitude of distance [rejection of these children], then it is unjustifiable. It goes against the humanistic norms of coexistence in our socialist society.’Footnote39 During the 1980s, Sieler was compelled to address parental concerns, particularly regarding the school maturity assessment, which many parents saw as a significant obstacle to their children’s education. Despite Sieler’s efforts to normalise the Sonderschule, the stigma persisted, and he revisited the issue years later, stating, ‘there is nothing wrong with a child attending a Sonderschule. Every child integrated there will find his or her place in life.’Footnote40 His interventions and the interventions of others did not appeal to scientific arguments but rather utilised their positions as experts to appease parental anxieties. Such interventions became more common during the 1980s, reflecting the parental worries that deeply concerned the population. Nevertheless, these public statements by experts ultimately fell short, as parents remained dissatisfied when their children were labelled as school immature and placed in Sonderschulen.

The Ministry of Education introduced new ‘guidelines for the admission of children to Sonderschulen’, which by the end of the 1970s resulted in a decrease of admissions to Sonderschulen.Footnote41 These guidelines sought to alleviate parental anxieties and discontent by advocating for a less stringent admission procedure, with the primary objective of placing only clearly school-immature children in Sonderschulen. This shift, in principle, changed the default decision, indicating that, unlike previously, in unclear cases children should be directed to standard schools. The ministry actively encouraged local cooperation between teachers and parents and was committed to ‘carefully analysing’ all complaints, a process that became more thorough throughout the 1980s.Footnote42 During that decade, the ministry issued reports on specific cases, providing detailed accounts of situations in which teacher’s decisions clashed with parental expectations. In response to complaints, the Department of Sonderschulen wrote that ‘in cases of doubt, a decision must be made in favour of enrolment in the standard school.’Footnote43 As reflected in the ministerial reports, many particular cases were overturned after complaints, and children were moved from Sonderschulen to standard schools, which satisfied parents.Footnote44 This sense of achievement in individual cases deterred parents from pursuing broader forms of complaint that could have placed greater strain on the state. However, the dynamics of the Eingaben system, unleashed and promoted by the East German state, had unintended consequences. The relative success did not content parents but rather encouraged others to further voice their complaints; the East German state struggled to process them accurately, up until the dissolution of the GDR. In the 1980s, as the ministry pointed out, there were more complaints than they could handle and ‘evaluation periods exceeded acceptable limits, and requested final reports or necessary interim information were not submitted on time.’Footnote45

This dynamic not only overruled expert diagnoses in favour of parental wishes, but also made a difference in school maturity assessments and schooling practices. The parental complaints, as they were mostly individualised, did not push for an alteration of the existing school maturity assessment and schooling structure; rather, they had the effect of adjusting the practical functioning of school admissions by softening the school maturity assessments. In the 1980s, the ministry recognised a ‘trend that has existed in recent years’; namely, ‘a decline in the number of children confirmed for attendance at Sonderschulen, both in absolute and relative terms’.Footnote46 That shows that while experts in media outlets concentrated on appeasing parents by showing the normality of Sonderschulen, the ministry accomplished minimising the enrolment of children in these schools as much as possible. The report continued: ‘This development makes it clear that the procedure is being carried out in a responsible manner […], and it has resulted in a further reduction in the number of underperforming children being transferred to Sonderschulen.’Footnote47 This demonstrates how parental pressure influenced the ministry to adjust its guidelines, taking greater risks by enrolling border case children in standard school, even if their potential school failure could negatively affect the low school failure statistics that the East German state wanted to showcase.

In Hungary at the beginning of the 1980s, when the number of school-immature children was on the rise, experts noticed an ongoing parental struggle to find ways to overturn a school immaturity assessment. Although the opening of many more corrective classes throughout Budapest and across the country came with a certain normalisation of the classes, pedagogues encountered difficulties in convincing parents to have their children attend them. Experts with experience in the field addressed the issue in print media for communicating to parents more generally, independent from individual cases. While experts continued to stress that corrective classes were not for disabled students, but for school-immature children, still a common misunderstanding in Hungarian society, they did acknowledge that the name ‘corrective class’ might evoke unfortunate associations. However, as psychologist Zsuzsa Flamm pointed out to the broad readership of the daily paper Népszava, a ‘corrective first class is not recommended by experts without justification, and therefore if parents, ignoring expert advice, enroll their unschooled child in a large class [standard class], they must take responsibility if the child starts the school year with a failure that may well mark the next eight years’.Footnote48 Another article in print media reported on a different worry expressed by parents who saw the problem not necessarily in attending the corrective class itself but somewhat later when their child moved on to a standard school class where new classmates might be prejudiced against them.Footnote49

Experts noticed the stigma parents attached to corrective classes. Although pedagogical research by Mrs. Zoltán Báthory and Vera Kántás agreed that some behaviours discriminated against children joining from corrective classes, their study showed that ‘the “corrective past” is by no means as decisive a handicap as we had assumed.’ However, they saw the main culprit for negative development in parents and schools alike: the outcome was especially unfavourable when both were impatient and incomprehensive towards corrective classes (Zoltánné & Kántás, Citation1983). The research provoked an engaged answer from sociologist Katalin Pik, who in turn passionately argued that children coming from corrective classes hardly become positive figures in the new class environment. She also wrote that these children often do not catch up academically; Pik pessimistically concluded that they ‘end up in a very unfavourable position in the micro-milieu of second grades, with no prospects for their future school careers’ (Pik, Citation1983). While corrective classes were, according to Pik, also socially relatively homogenous, parents reacting to the stigma would not ‘let their child go to corrective class even after careful explanation and persuasion’ (Citation1983). Thus, the stigma produced and reproduced by parents, children, and sometimes even pedagogues and school management shaped expert assessments of corrective classes.

In this ambivalent climate surrounding corrective classes, the Hungarian Ministry of Education decided in 1987 to abolish and replace the corrective classes with ‘small-sized classes’, reasoning that corrective ‘classes could not eliminate individual disadvantages to the extent expected, in many places, they were given the worst accommodation and the least suitable teachers instead of the best conditions, and the name itself had become stigmatising’ (Koncz, Citation1988). Since the decision occurred at a time when the number of school-immature children was growing year by year, experts did not recommend bringing the pedagogical experiment to a halt as institutional support was greatly needed. The ministerial decision was also part of a broader attempt to decentralise the school system by shifting the responsibility from district administration to individual schools, which were free to decide if they wanted to offer small-sized classes (Koncz, Citation1988). But, unfortunately, where there had not been enough infrastructure and means for corrective classes, small-sized classes were unlikely to flourish (Koncz, Citation1988).

Simultaneously, new regulations issued by the state assigned greater freedom to parents during the process. Although it lay in the responsibility of the kindergarten teacher to assess the school maturity levels of the children, parental approval was needed for the final decision. When kindergarten teachers and parents could not agree on a joint position, the Educational Guidance Centre would serve as an intermediary and have the last word in the process (A. Horányi & Ormai Kósáné, Citation1988). However, experts from the Guidance Centre needed to act transparently by sharing their findings with the parents, allowing them to comprehend the expert recommendation’s evidence fully. If the child was assessed as immature for entering school, parents had the freedom to decide if they wanted their child to stay in kindergarten or attend a small-sized class (G. Horányi, Citation1988). Ultimately, parents received greater agency in determining the further trajectory of their child’s schooling in the interest of alleviating previous tensions in connection with corrective classes.

However, the substantial integration of parents into the decision-making process did not always lead to positive results. As voiced by experts, many parents pressured (sometimes violently) kindergarten teachers to issue a school maturity assessment, which, unfortunately, in many instances, created problems for children later on (G. Horányi, Citation1988). Furthermore, experts pointed out that a sizeable number of children who attended kindergarten for another year still showed insufficient school maturity levels at school entry (Hamrák, Citation1988), and some socially immature children even ended up in special schools (G. Horányi, Citation1988). At the end of the 1980s, the dusk of the socialist state, the newly gained freedom came with a price: A growing number of school-immature children and their parents could no longer rely on widespread structured support, and the agency of parents, often resulting in eigensinniges behaviour, might have worked against the actual needs of the child.

5. Conclusion

In this article, we have advanced Eyal’s sociology of expertise by extending the concept beyond citizens as ‘lay experts’. Unlike Eyal’s framework, which focuses on citizens as ‘lay experts’ contributing to expertise networks, we have demonstrated that even parental complaints, devoid of any claimed expertise, influenced expert decisions and state policies. By doing so, we have scrutinised the possible impact of parental discontent on state policies in contributing to the workings of power and the formation of networks of expertise in state socialist societies. The motivation of parents to involve themselves was often triggered by social factors such as status anxiety and judgment from their social surroundings. Parents perceived a growing stigma if their children were to be enrolled in corrective classes or sent to Sonderschule, fearing they would never return to a ‘normal’ educational path. By showing the underlying motivation of parents through the application of the Eigensinn concept, we have furthered the understanding of how networks encompass actors who are neither experts nor lay experts. We therefore added a complementary explanation on how and why parents enter a network of expertise with the possible outcome of shaping expertise.

We showed how the 1960s introduction of school maturity assessments in Hungary and East Germany made the problem of immature children more visible and more socially discussed. Although school maturity was similarly understood in both countries, the solutions each state provided differed greatly and children attended contrasting forms of schooling. In East Germany, the Sonderschule hosted most of these immature children; in Hungary, corrective classes were put in practice in the mid-1960s with the aim of guaranteeing an equal start to those less developed children. In Hungary, the corrective classes were meant as a temporary solution anticipating that the children would catch up and be later integrated into normal schools. The East German Sonderschule, by contrast, had an almost permanent nature, perceived as a final and irreversible deviation from a standard school system, potentially turning into a cul-de-sac. Although in theory children could eventually return to standard schooling, in practice it happened rarely.

Despite this significant difference in the schooling for school-immature children, parental discontent revealing different notions of normalcy grew during the 1970s and was especially profound in the GDR. The extent of the stigma differed between the two countries. In East Germany, parents perceived that their immature children could never pursue a standard school trajectory. As the Sonderschule usually turned out to be a dead-end for the child, the stigma was more profound; in some cases, parents even feared a higher likelihood that their children would become criminals. We have shown that the criminological expertise which correlated Sonderschulen with youth delinquency exacerbated these parental preoccupations. In Hungary, parents expressed their opposition towards corrective classes mostly by challenging the school maturity assessment. Although school maturity issues occurred across all strata, it was more likely for children of lower classes to attend corrective classes. Middle-class parents, however, perceived the stigma more intensively and were more likely to use their social capital to prevent their children from attending corrective classes. These practices, revealing a great deal of Eigensinn, contributed to an increasing stigma of these classes. This stigma contradicted the egalitarian approach by which any late developing child, no matter their family background or ethnicity, should attend corrective classes. Instead, corrective classes mirrored social differences already present in Hungarian society on a larger scale. In East Germany, remarks on social differences or class did not appear and parents focused instead on adapting to the centralised Eingaben complaint system, whose existence conditioned the way parents addressed their grievances to the state.

In Hungary, parents made use of multiple avenues for challenging a school immaturity assessment; in East Germany, the Eingaben became the first procedure parents attempted in expressing their Eigensinn in their quest for normalcy, which provoked a twofold consequence. First, it standardised the complaints and maintained them in a form and tone that complied with official procedures and therefore contributed to the reproduction of social practices that maintained the power structure of the socialist state. Second, as the East German state promoted Eingaben complaints that often satisfied parents, they did not decrease but rather increased after the late 1970s, giving rise to unintended consequences. By that time, pedagogues and teachers addressing the Ministry of Education blamed parents who lacked sufficient insight to decide whether a child was mature enough to enrol in standard schooling. However, a high influx of parental complaints blaming teachers’ assessments that went against the parental understanding of normalcy forced the ministry to side with the parents, and parents in most cases challenged experts’ opinions and were able to condition school maturity assessments.

In the 1980s, in both Hungary and East Germany, parental pressure made a difference in school maturity and schooling policies, albeit in different ways. In Germany, the system was not altered, but the way it functioned changed. As the ministry received more complaints than it could handle, the ministry decided to relax the admission procedure, sending children to standard schools by default. Yet parents were not officially included in the decision-making process. In Hungary, on the contrary, the dynamics of the 1980s economic crisis and the decentralisation of the education system led the ministry include parents more directly in school maturity and schooling practices, giving parents greater agency to decide on the solution most suitable for their child. The kindergarten teacher became a crucial figure for the decision if the child was sufficiently mature to enter school while both the teacher and the parents needed to agree on the assessment, turning parents into almost equal partners within the admission process. An ambivalent professional expertise and the popular stigmatisation of corrective classes pushed the ministry to replace them in 1987 with small-sized classes to alleviate the stigma that had surrounded them. However, the move towards the liberalisation of the admission procedure resulted in unintended consequences. On one hand, it decreased institutional support at a time when the numbers of school immature children were on the rise. On the other hand, a state in retreat allowed for growing agency in parents, often resulting in eigensinniges behaviour that ultimately might have worked against the actual needs of the child. In Hungary, the changes were more profound, as they affected state policies; in East Germany, on the contrary, the state retained relative stability of its education system but its school admission process was severely altered. For both countries, this article has shown how parental Eigensinn and their understanding of normalcy not only overruled expert assessments but shaped how two socialist authoritarian states worked on the ground.

5.1. Archival sources

SAPMO-BArch (Archive of the Foundation of the Parties and Mass Organisations of the GDR in the Federal Archives, Berlin)

MNL (National Archives of Hungary, Budapest)

BFL (Budapest City Archives, Budapest)

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to the members of the ExpertTurn research team and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The special education settings we refer to in the article were not devoted to mentally disabled children, but to children showing insufficient or slow development who were thus deemed immature for standard schools and redirected to other types of schooling.

2. Although the technical term in English is ‘remedial class’, for analytical reasons, we settled on a close translation of the Hungarian wording ‘korrekciós osztály’ and therefore use ‘corrective class’ throughout the article.

3. Although letters for the 1980s are not (yet) accessible in the archives, we hypothesise that parents had less reason for disagreement in the 1980s due to the changing state policies regarding the school maturity assessment and to the general trend of de-centralising the education system.

4. Literature on remedial classes from a historical perspective is still rare. See e.g (Hjörne & Larsson, Citation2012).

5. Gagyiova, A. (2023). Every Child According to Its Pace: School Maturity between Expertise, State Policies, and Parental Eigensinn in Socialist Hungary. Hungarian Historical Review 12(3), 461–92. https://doi.org/10.38145/2023.3.461

6. Gesetz zur Demokratisierung der deutschen Schule, 1946.

7. Erziehungsprogramm der Krippen 1961, SAPMO-BArch, DR2/20515.

8. Zum Problem der Schulreife, der Grundlagen und der Methoden ihrer Bestimmung, 1962, SAPMO-BArch, DR2/20515.

9. In East Germany, there was a complex system of special schooling grouped under diverse categories. Sonderschulen and Hilfsschulen were part of it, and within those were other subdivisions that further complicate the picture. For the sake of clarity, in this text we use Sonderschule as a generic category. Translating Sonderschule into English as ‘special school’ might be misleading and imply that we are referring to schools for disabled children only, which we are not. Instead, as explained, we analyse children deemed immature who, in all cases, were educable and not mentally impaired.

10. Zum Problem der Schulreife, der Grundlagen und der Methoden ihrer Bestimmung, 1962, SAPMO-BArch, DR2/20515.

11. SAPMO-BArch, DQ1/6472. 1963.

12. Eingabenanalyse 1976, SAPMO-BArch, DR2/29336.

13. (1967, August 26). Vor dem Gang mit der Zuckertüte. Über pädagogische und psychologische Probleme bei der Einschulung. Neue Zeit, 4.

14. (1969, August 6). Wer entscheidet darüber, wann ein Kind schulfähig ist? Neue Zeit, 7.

15. Carola, S. (1987, April 18). Unbedingt in die Sonderschule? Berliner Zeitung, 11.

16. SAPMO-BArch, DR2/51349, 23.6.1980.

17. SAPMO-BArch, DR2/51349, 21.5.1980.

18. (1956, December 4). Zweimal Kriminalstatistik. Neue Zeit, 2.

19. SAPMO-BArch, DR2/51349, 23.6.1980.

20. Bel. (1970, March 16). Megy a Gyerek, Iskolába. Esti Hírlap, 2.

21. Berke Kálmán panasza, MNL XIX-I-8-b. 8. doboz, 19 August 1977, Oktatási minisztérium, Panasziroda, MNL.

22. Ibid.

23. Bognár Mihályné panasza, 18 August 1975, MNL XIX-I-8-b. 4. doboz, Oktatási minisztérium, Panasziroda, MNL.

24. Sz. (1984, 23 August). Ludas Matyi, 12.

25. Bakti Béla panasza, 24 May 1979, MNL XIX-I-8-b. 12. doboz, Oktatási minisztérium, Panasziroda, MNL.

26. Jandovics Ferenc panasza, 13 September 1978, MNL XIX-I-8-b. 10. doboz, Oktatási minisztérium, Panasziroda, MNL.

27. MNL OL P 2224. 9–11. tétel. Pik Katalin hagyatéka, 1940–2001 (Csongor, Citation1978; Faragó, Citation1966).

28. A tankötelezettségi törvény végrehajtásának tapasztalatai, 7 July 1976, Budapest Főváros Tanácsa Végrehajtó Bizottsága üléseinek jegyzőkönyvei, BFL XXIII.102.a.1., Budapest Főváros Levéltára [Budapest City Archives], Budapest.

29. Bartus Lajosné panasza, 23 April 1979, MNL XIX-I-8-b. 12. doboz, Oktatási minisztérium, Panasziroda, MNL.

30. Ibid (Faragó, Citation1966; Szabó, Citation1967, Citation1969).

31. Ildikó Avarné Császár, A Gellérthegy utcai iskola – I. iskolaotthonos osztállyal kapcsolatos munka összegezése, 16 March 1973, HU BFL XIII.3709.a, Nevelési Tanácsadó I. kerület, BFL, Budapest.

32. Gulyás Anita panasza, 21 November 1978, MNL XIX-I-8-b. 13. doboz, Oktatási minisztérium, Panasziroda, MNL.

33. Zur Schulfähigkeitsdiagnostik. Methodologische Frage und Ergebnisse, 1973, SAPMO-BArch, DR200/10053.

34. SAPMO-BArch, DR2/51349, 12.4.1980.

35. SAPMO-BArch, DR2/51349, 23.6.1980.

36. Eingabenanalyse 1979, SAPMO-BArch, DR2/29336.

37. Eingabenanalyse 1978, SAPMO-BArch, DR2/29336.

38. (1977, March 15). Fernsehprogramm. Berliner Zeitung, 10.

39. Sieler, W. (1982, July 24). Wird unser Kind schulfähig sein? Berliner Zeitung, 11.

40. Sieler, W. (1987, April 19). Unbedingt in die Sonderschule? Auf das Leistungsvermögen zugeschnittene Lehrpläne. Berliner Zeitung, 11.

41. Abteilung Sonderschule 1978, SAPMO-BArch, DR2/29336.

42. Analyse der Eingaben zu Einsprüchen gegen die Aufnahme von Kindern in die Hilfsschule und Vorschläge für das weitere Vorgehen, 1981, SAPMO-BArch, DR2/29336.