Abstract

Research, as well as mainstream culture, may be too quick to label parenting young people of color (which we define as being under or near the age of 20 when having a child) as delinquent and “at risk”. Using qualitative data, we offer anti-deficit framing surrounding students of color with children, highlighting the unique achievements of a set of “parent-strivers” despite the natural challenges of unexpectant parenthood. Our findings suggest that the parenting and academic identities of low-income people of color can be mutually beneficial and reinforced through positive schooling influences; we challenge the idea that education becomes a secondary priority after one becomes a parent. This paper answers the call for a better “articulation of agency” within exclusionary institutions. It contributes a rare acknowledgment of positive family outcomes to offset the concept of risk monopolizing the field and leaving us without support-oriented thinking.

Introduction

Reframing the notion that young parents cannot strive toward educational pursuits

I feel like I’ve been helped a lot. I haven’t had the hardest road to travel, when compared to other people. Who am I to complain? There’s always solutions. Even when I’m weak, I feel like it’s okay because I’ll do better tomorrow. I got air in my lungs; I got my kid next to me and family. That’s what I focus on if I have negative thoughts.

—“Malcolm,” 27

“Malcolm” has just described his experience with homelessness after his mother kicked him out of his childhood home. He is holding his five-year-old daughter during this interview. His childhood was tough: his mother had been professionally diagnosed with bipolar disorder and shortly after, his father left home. A few years following this period, around when Malcolm was 21, his girlfriend became pregnant. They now live together and co-parent their daughter with help from the girlfriend’s mother. Malcolm is a first-generation college student and currently works as a store manager. He displays a strong work ethic and is eager to share his unique perspectives and his life experiences with others. These traits make him seem invaluable to the college environments he enters. Much of his return to education and newfound positive disposition toward schooling experiences can be directly tied to fatherhood, which seems surprising given his strained relationships with his parents. His daughter and family give him optimism and confidence, reminding him of how he was helped by others (Adapted fieldnote, December 2017).

Malcolm was explicitly chosen to be profiled in our introduction because his story may inspire other young parents from low-income backgrounds seeking postsecondary degrees. He is a Black man, wearing a loose-fitting hoodie and jeans; he has tattoos on his neck and has long hair tied up in a braid. He was once a high school dropout and homeless, taking bird baths in the sinks of public parks during the day and working a shift as a building doorman to have some shelter at night. Given societal expectations and so much existing literature, educational scholars and practitioners might be surprised by Malcolm’s story and his educational pathway to attaining an education. This indicates a more significant societal problem related to holding diminished expectations for those who have nontraditional academic and professional trajectories. Though Malcolm’s is unlikely to be the traditional profile one would conjure when thinking of a typical college student or involved parent, he is both. He has brought his daughter with him to the research interview so he can watch her.

In this paper, we offer a retort to normalized beliefs around young parents being under or near the age of 20 and their weakened potential to achieve an education once they become parents. Specifically, we are critical of sweepingly applying the concept “risk factor” to describe the case of students who become parents at a younger age, often unexpectedly. Our position is that this kind of labeling can be defeatist. In contrast, we are more interested in expanding the discourse around how to support better the parenting populations of any age, ethnicity, and community background. We contribute to a narrow but expanding body of asset-based literature on students of color from low-income backgrounds. However, these perspectives have rarely been applied to parenting students to date.

Early parenthood (which we define as being under or near the age of 20 when having a child) is almost always deemed a “risk factor” and problematically tied to a lack of intelligence and consequential thinking (Aslam et al., Citation2017; Division of Reproductive Health, Citation2021b, August 21; Langley et al., Citation2015). “Risk” appears to describe serious impediments to one’s academic performance and the formation of positive mental health and well-being. Youth most characterized as being at-risk tend to be of color from low-income backgrounds, which in turn are also demographic predictors of early parenthood and delinquency (Corcoran, Citation1998; Farb & Margolis, Citation2016; Fernandes-Alcantara, Citation2018; Hoeve et al., Citation2009; Hoskins & Simons, Citation2015; Kann et al., Citation2016). The U.S. continues to have one of the highest rates of teen pregnancy among teens between age fifteen and nineteen, with one in four girls becoming pregnant at least once by age 20 (Blackman, Citation2018). In a large-scale research project published by the National Institute of Health (NIH), it was found that among teenage females growing up in poverty, 16.8% had been pregnant at least one time by the age of seventeen (Garwood et al. Citation2015). For those who grew up in poverty and had reported experiencing childhood abuse or neglect, 29.8% had been pregnant at least once by seventeen (Garwood et al., Citation2015).

Better understanding these phenomena requires a deeper conversation around social structures and support systems—not simply basing outcomes on behavior alone. As we will argue, these perceptions are at least limited, mainly when applied to young parents who may simply need the influence of more positive relationships and opportunities to reclaim their educational trajectories. We will aim to make the case that young parents, like other students, are on the cusp of exploring various life possibilities. While becoming a parent may necessitate a pause or lengthy self-removal from an educational pathway, it does not have to be an education “death sentence” and confirmation of a self-fulfilling prophecy that a school is no longer a place where one belongs (Emler & Reicher, Citation2004; Kundu, Citation2020; Merton, Citation1948).

Using qualitative evidence and firsthand narratives we offer an antideficit perspective to the larger body of sociology of education and developmental scholarship concerned with “strivers,” or high-achieving, underserved students from low-income backgrounds (Brody et al., Citation2016; Kundu, Citation2019). Striver literature is overly concerned with the admirable qualities of young people from disadvantaged backgrounds, potentially neglecting the fundamental challenges these young people routinely encounter as well as the multilayered processes required to triumph with challenges in tow.

Though limited, our unique sample of “parent-strivers” indicates that individuals can develop new senses of self and educational motivations sometime after entering parenthood, especially for students with no previous affinity toward academic pursuits (Kundu, Citation2017, Citation2020; Neale & Davies, Citation2016; Watson & Vogel, Citation2017). These narratives of success go against many socially prevalent ideas, including the pervasive belief that men of color are prone to becoming absentee fathers (Neale & Clayton, Citation2014; Robbers, Citation2009; Sipsma et al., Citation2010). By amplifying the voice of these individuals (who are often left out of assessments and dialogues about their potential to succeed), our findings also challenge notions that low-income families value education less than others or that they are resentful of such opportunity systems (Carter, Citation2005; Fordham & Ogbu, Citation1986; Shedd, Citation2015).

We hope to connect our research to practice and provide insights on how to support the parenting student population more holistically through identifying the types of support we believe could leverage the motivations and attitudes of young parenting students to help them achieve their goals despite their roadblocks. We consider and highlight that the parenting student population in the United States is broad. No one term adequately represents the intersectional identities and realities of students, their children, families, and the different family-oriented lifestyles they manage while caring for their children and seeking an education.

Review of literature

The literature review focuses on understanding parenting students’ potential and interest in expanding their education to provide for their children and families. For this study, we turn to a group of individuals who became parents in their youth (under or near the age of 20). This section of the paper discusses the challenges of teen births and their connection to academic difficulties and economic distress. Then, we talk about the outcomes of the parenting population in postsecondary education and the support they need while seeking higher-education credentials.

Teen births challenges in the United States

The impact of high school students dropping out after becoming parents has economic disadvantages. Research reports that there is a critical need to support young parents because teen pregnancy is connected to the rate of high school dropouts and academic challenges among youth in the United States (Arnett, Citation2004; Farb & Margolis, Citation2016; Fernandes-Alcantara, Citation2020; Shuger, Citation2012; Solomon-Fears, Citation2016). Although the rate of teen pregnancy for females in the US has declined from 17% in 2018 to 16% in 2019 (Division of Reproductive Health, Citation2021a), teen births continue to be higher among girls of color. In 2019, the Division of Reproductive Health (Citation2021a) reported that the number of “Hispanic teens (25.3) and non-Hispanic Black teens (25.8) were more than two times higher than the rate for non-Hispanic White teens (11.4)” (p. 1). The same report said American Indian/Alaska Native females had the highest birth rates (29.2) among all race/ethnic groups (Division of Reproductive Health, Citation2021a).

In addition, an abundance of scholarship links early parenthood to intergenerational inequality (Barcelos & Gubrium, Citation2014; Huang et al., Citation2014). The topic of parenting youth, or “kids with kids,” has been reported to have socially reproductive implications on poverty and social mobility (Aslam et al., Citation2017; Corcoran, Citation1998; Kenney, Citation1987). Scholars discuss predictive factors of poverty, diminished educational attainment, and increased “sexual risk behavior” as outcomes for young parents and their children. Research also reported that children of young men who became fathers before 20 were roughly three times more likely to have children as adolescents than children born to older fathers (Sipsma et al., Citation2010). On a positive note, some research reports that parents attaining a postsecondary education is their way of elevating economic strain and providing for their children.

The parenting population in postsecondary education

Parenting students may return to school to complete requirements for credentials, support career advancement, and/or transfer to a university to advance their education. Nationally, the number of parenting students enrolled in postsecondary education increased from 3.7 million to 4.8 million between 2004 to 2012 (Noll et al., Citation2017). National data reports that more than a quarter of all undergraduates are raising children and that 44% of students seek an education alone without a partner (Kruvelis, Citation2017). Kruvelis (Citation2017) found that 80% of students caring for children alone are women. More than a quarter are American Indian/Alaskan Native, 40% are Black mothers, 19% are Latina, and 14% are White. In addition, parenting students often have limited financial resources to contribute to their educational attainment beyond secondary schooling (Anderson & Nieves, Citation2020; Duke-Benfield, Citation2015; Gault et al., Citation2014). They rely heavily on financial aid, such as the Pell Grant, scholarships, and other funding sources to fund their education (Baum & Steele, Citation2017; Gault et al., Citation2014; Kaushal et al., Citation2011).

When it comes to enrollment, parenting students often enroll at two-year colleges because they offer a variety of credentials and training in trade professions, such as associate degrees and certificate programs, career and technical education, primary adult education, remedial education, and dual enrollment for high school students, not to mention they are a fraction of the cost of traditional four-year colleges (Anderson & Nieves, Citation2020; St. Rose & Hill, Citation2013). Then, when considering college completion, 53% of parenting students versus 31% of non-parenting students are at risk of leaving college without degrees or credentials after six years (Nelson et al., Citation2013). Among lower-income college students with children, Nelson et al. (Citation2013) report that 25% percent of parents are less likely to obtain a degree than lower-income college students without children. All in all, parenting students face unique challenges and need specific resources that single status students without children may not require.

Parenting students’ need of support in postsecondary education

Young families are often written about using hopeless and undignified language (Barcelos & Gubrium, Citation2014; Huang et al., Citation2014). Students of color are portrayed as poverty statistics and failed educational outcomes rather than individuals with more promising futures if supported by higher education institutions. Schumacher (Citation2013) says higher education institutions must intentionally practice inclusiveness for parenting students at their campuses. She suggests that colleges and universities make their campuses more welcoming and responsive to parenting students by providing student support services. Other studies suggest implementing more campus policies and programs specifically directed to support mothering and fathering students (Miller et al., Citation2011; Nelson et al., Citation2013; St. Rose & Hill, Citation2013). For example, access to affordable childcare and financial aid assistance are found to be critical necessities for parenting students with younger age children and for lower-income families and households (Arcand, Citation2015; Goldrick-Rab et al., Citation2011; Miller et al., Citation2011; Perez, Citation2016; Peterson, 2016).

Even though most of the literature talks about mothering students’ challenges and outcomes in attaining higher education credentials (Arcand, Citation2015; Hernandez & Abu Rabia, Citation2017; Huang et al., Citation2014; Perez, Citation2016; Perez & Turner, Citation2020; Watson & Vogel, Citation2017), the voices of fathering students are underrepresented in the literature, especially since there is an abundance of research on the estrangement of young men of color from educational institutions where they are unable to form positive relationships with role models or identities of academic achievement (Jack, Citation2019; Kundu, Citation2020; Noguera, Citation2008; Ransaw et al., Citation2018). It stands to reason that cultivating the belonging of young women and men of all ages within schools would prevent adverse life outcomes and promote intergenerational prosperity. Even more, amplifying the voices of successful mothers and fathers of color—something we hope to achieve here—who became young parents seems like an apt approach to surfacing systemic solutions and addressing the gap in the literature about the academic success of Black and Latinx parents of color.

Theoretical framework

Parenting students’ agency as an asset-based framework and parenting identity as an asset

Despite an extensive body of research on parenting youth, there is a dearth of literature on the positive outcomes of parenting students (Cherrington & Breheny, Citation2005; Kundu, Citation2020; Watson & Vogel, Citation2017). This study was conducted to articulate how the identity of parenthood can facilitate academic success and was intended to challenge predominantly held deficit notions of parent-studenthood as an individual failure (Cherrington & Breheny, Citation2005). We develop the theme of personal success related to one’s agency, or “a person’s capacity to leverage resources to navigate obstacles and create positive change in their life” (Kundu, Citation2020, p. xviii). An agency framework provides a comprehensive, ecology-conscious model for positioning a student’s abilities to overcome barriers to traditional success such as early parenthood; considering agency implicitly acknowledges the existence of structural forces such as poverty and goes beyond connecting student outcomes to their behavioral choices (Emirbayer & Mische, Citation1998; Kundu, Citation2017, Citation2018, Citation2020; Nagaoka, Citation2016).

Interactions between educators and low-income students from minoritize populations are often informed by biases about what students can achieve academically (Barcelos & Gubrium, Citation2014; Cherrington & Breheny, Citation2005; Freire, Citation1968; Simone, Citation2012). For this reason, this study focuses on low-income parenting students of color and how they navigate formal education systems to achieve educational success. To understand the conditions of parenting students of color, we turn to Yosso’s community cultural wealth to guide the analysis process. Yosso (Citation2005) asserts that people of color carry their forms of capital (aspirational, familial, social, navigational, resistant, and linguistic capital) that expand beyond Bourdieu’s (Citation1986) cultural capital theory. She defines community cultural wealth as an “array of knowledge, skills, abilities, and contacts possessed and utilized by Communities of Color to survive and resist macro and micro-forms of oppression” (Yosso, Citation2005, p. 77).

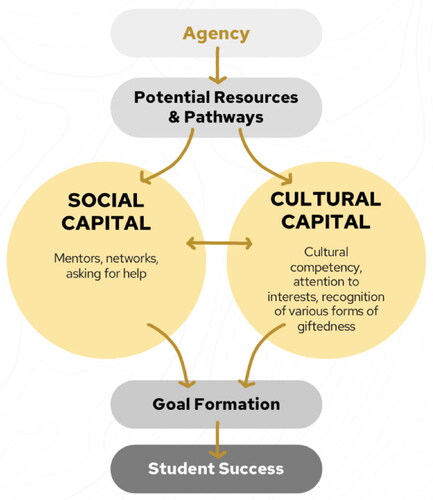

The cultural wealth gap that exists at higher education institutions is structured around power and dominance that align more with middle-class values and higher socioeconomic families (Bernal et al., Citation2000; Goldthorpe, Citation1997; Stanton-Salazar, Citation2011; Stuber, Citation2011; Yosso, Citation2005). This type of structure causes students of color and other minoritize student populations, such as parenting students of color, to struggle and encounter challenges caused by inequity practices and policies (Perez, Citation2016, Citation2020; Bowles et al., Citation2009; Bowles & Gintis, Citation2002; Goldthorpe, Citation1997; Hout & Janus, Citation2011). Efficiently tapping into social capital (e.g., mentors, utilization of networks, and one’s general disposition to ask for help) and/or cultural capital (e.g., culturally competent environments or a mentor who recognizes that giftedness takes many forms) can help young people form and articulate goals that are aligned to the culturally dominant construction of success and achieve goals that beget tangible rewards (Kundu, Citation2020). This framework provides a valuable way of understanding and organizing the thematic findings that we share in this paper (, see Appendix A).

Broadening the discourse surrounding parenting students

Conditions correlated with teenage pregnancy, such as neighborhood and income, are more accurate predictors of student outcomes and social trajectories than the occurrence of pregnancy itself (Watson & Vogel, Citation2017). However, discussions on teenage pregnancy within educational institutions in the United States have ranged from pregnancy as a personal and moral failing to preventative and harmful “contamination discourse” (Cherrington & Breheny, Citation2005; Watson & Vogel, Citation2017). We position this study against these “dominant constructions” about teenage pregnancy (Cherrington & Breheny, Citation2005) by developing a model of strategic narratives (Barcelos & Gubrium, Citation2014). Through “portraiture,” or intentional selection and amplification of participant voices (Watson & Vogel, Citation2017), we provide the personal experiences of 10 successful families with the goal of making their stories useful in the conversation on how to support such students broadly.

Methodology and data

Framing and basic design

Qualitative research that relies primarily on interviews is appropriate to learn about the internal contexts and rationales that direct human behavior (Rubin & Rubin, Citation2011). These studies are designed to understand the meanings individuals assign to their choices. In this paper, we use qualitative data from interviews to support the specific theory that low-income Black and Latinx parent-strivers can increase their ability to obtain academic and professional goals and their sense of agency after entering parenthood. This specific finding unexpectedly arose from a larger, qualitative sociological study (n = 48) conducted by the first author of this paper on the achievements of young adult students of color who grew up below the poverty line and faced social and economic disadvantages, defined below.

Through the inductive research process, the first-author/researcher noticed trends emerging among the parents in the larger sample, which led him to organize more general themes around their experiences. In particular, he observed striking commonalities within the subset of parents related to their rationalization of specific goals, the articulation of parenting identity, and orientation toward long-term thinking. This prompted him to design a follow-up project, for which he enlisted the support of the second and third-authors, solely focused on deeply investigating the data from the 10 participants who were parents from the initial sample. Subsequent themes were uncovered through the inductive research process or by searching patterns from generalized observations.Footnote1

Individuals who contend with social disadvantages often simultaneously experience racial, ethnic, or cultural prejudice. We also claim that these individuals do not have access to the kinds of social capital that naturally beget economic rewards (e.g., a connection to someone who can help them get an internship). Students who experience economic disadvantages fall under the classifications of the Federal poverty guidelines and therefore qualify for specific programs, such as free school meals (Schacter & Jo, Citation2005). Each of the participants in the larger study met these basic social and economic disadvantage qualifications.

The data and sample for this specific paper were separated and examined in greater detail through a different lens and new research questions separate from the larger original study. The following research question and sub-question guide this study’s inquiry: How do college-educated Black and Latinx professionals describe their relationship to education and how it changed over time, specifically after they became parents? Further,

How does parenthood contribute to one’s attitude about education and educational pursuits?

The qualitative framing of these questions helped identify how young people grapple with new identities of parenthood and their experiences before and after having a child.

Participant recruitment, selection, and interviews

Students were selected to participate in the larger research project through the recruitment of two after-school enrichment programs that send New York City high school students to college. Both programs choose students based on the need-based qualifications described above. Each participant graduated from one of these programs. Through email outreach, participants were informed that this study sought to include individuals who have faced different challenges in their lives and aimed to learn about overcoming these obstacles and achieving goals. At the time of the interview, each participant either attended a bachelor’s degree-granting college or had recently graduated with their bachelor’s credential and had been working in a professional, upwardly mobile occupation and/or was attending some graduate school. All of the participants were over the age of 20 at the time of their interviews. Their stories about being expectant parents and how they managed to advance their education spoke to the resilience and powerful impact of parenthood on educational advancement.

From an initial sample of 48 individuals, 10 self-identified as “parenting students,” which was those who had a child in their teenage years or had a child while a college graduate. See in Appendix B for more details. The data from which this paper is derived consists of transcripts from 10 face-to-face, semi-structured interviews (equal to 12.5 hours of audio) with a sample of “emerging adult” participants between the ages of 26–29 (Arnett, Citation2004) except for one older participant, aged 44. This included four females (two Black/two Latinx) and six males (four Black/two Latinx). At the time of the interviews, all but one participant had completed four-year college, with the last participant having one year left before earning their degree. Three of the participants were master’s-level graduate students (two had graduated and one was nearing completion), and one was in law school and had also subsequently graduated. The other participants work in different professions (e.g., teacher, counselor, academic advisor, management, finance, and nonprofit).

Through semi-structured interviews, participants were asked broadly about the challenges they experienced and continue to contend with. Interviews typically lasted 70 minutes, generated from a protocol that followed and probed at natural trends and progressions in dialogue (Rubin & Rubin, Citation2011). The format allowed for flexibility so that ideas could be elaborated on at the moment, even though interviewees were asked the same set of primary questions (Underwood et al., Citation2010). The primary researcher transcribed all interview audio and recorded analytic memos to map and chart commonalities after each interview. The researcher used Dedoose, a qualitative data analysis software, to organize and code interview transcripts.

Emergence of parent-striving as phenomena

New memos were cross-referenced against other notes from the initial study and more recent interviews to create a database of primary keywords that supported or nuanced the earliest findings and commonly occurring ideas in transcripts. During coding, memos were used to identify developing patterns through inductive reasoning or broad inferences from more specific observations (in this case, parenting became an observation of interest). The inductive process helped position these participants’ narratives within the broader context of strivers and striver research while allowing the researcher to investigate, challenge, and add to existing theory (Ary et al., Citation2013; Griffee, Citation2005). The subset of participants was analyzed separately after the emergence of “parent-studenthood linked to agency” as a critical theme.

Parental status was a common factor that increased participants’ agency and desire to follow through on successfully attaining their educational and personal goals. In particular, this method challenged the theories that young and unplanned parenthood is consistently associated with delinquency and adverse academic, professional, and life outcomes. Instead, the data indicated the opposite for this subset of individuals: that parenthood was linked to pivoting in a direction opposite from delinquency and stagnation. Code co-occurrence charts in Dedoose showed a particular subset of individuals—specifically those marked as parents, and that goal orientation was primarily associated with their identity as parents.

Strategic narratives through portraiture

The goal of this work is not to display prevalence or proportionality but instead is meant to indicate a purposeful sampling and inclusion of participants. It is working more closely with 10 participants provided for in-depth narratives that critique so-called dominant constructions or generally accepted ideas by mainstream culture (Cherrington & Breheny, Citation2005). We acknowledge the emotional, social, and financial difficulties of parenthood for those under or near 20 years old; however, this study was performed to better understand parenting students’ potential achievements. Building off a framework of simple resilience (Watson & Vogel, Citation2017), we position these narratives not as a success despite parenthood, as is the general bent of the asset-focused work that does exist, but rather as success that is mainly motivated by a relationship with one’s child catalyzed by the identity of parenthood itself. All individuals included in this subsequent research investigation were able to, in some sense, reframe their initial educational struggles following parenthood in a way that gave rise to new motivations to succeed. This paper shares what was learned from these parent-strivers on how to develop mutually beneficial academic and parenting identities and obtain the support necessary to advance one’s educational trajectory.

Summary of findings

Two significant findings emerged from this study and the interviews conducted around answering the research question and sub-question described. The first thematic finding is that parenting students appear to be better able to reflect on their social position, obstacles, and potential, after having a child. More specifically, parent-strivers develop strong articulations around their newfound responsibilities as guardians and example-setters. Secondly, parents express gaining a sense of purpose after becoming parents, which motivates their interest to develop their educational advancements and careers. They credited their children, even infants, for helping catalyze their ability to create more clarity about their ambitions to further their education. Participants discussed their educational pursuit as integral to their long-term parenting strategies and desire to model their educational advancement for their children.

Newly developed identities and motivations to be an “example-setter” and provider

Participants commonly explained developing a more robust understanding of their actions’ immediate power and consequences, specifically in terms of effects on their children’s lives. Before children, there was less at stake. This kind of premeditated and reasoned action-taking is a vital component of human agency (Kundu, Citation2018; Nagaoka, Citation2016) as well as informed and evolving praxis, or the intersection of action and reflection related to an increased understanding of one’s limited situations in life and how to overcome them (Freire, Citation1968). For example, “Roxanne” described that a large part of the reason she works so hard in her job is that financial stability will help her daughter have a more structured life. Upon probing further about why structure is so important to her, Roxanne described in greater detail how she wanted to parent her child, which was dissimilar to the approach of her mother:

Well, for one, I wasn’t as close to my mom as I wanted to be. She’s a great person and provider, but she wasn’t as nurturing as I would have liked. I didn’t feel like she was open with me, which probably led to me getting pregnant earlier. If [she] was more disciplinary, and I knew I couldn’t do certain things, it would have helped. But I did get pregnant at a young age. When I think about raising my daughter, I try to be more open, not be afraid of having conversations.

Roxanne also enthusiastically expresses that she is pleased to be a mother but says it is challenging. She wants her daughter also to be free from similar constraints and stresses she had due to growing up poor and becoming a young mother. These motivations connect with her diligence and desire to succeed at work because taking care of her child in this way is implicitly tied to her incentive to curb the intergenerational inequality that her family has experienced.

There is an inherent power in saying that these challenges end with her—that her motherhood became both an experience and platform for better realizing strategies that should promote the eventual mobility of her daughter. Similar sentiments were echoed by all the parenting students included in this paper. Roxanne grew up very poor but could finish college in her mid-twenties. At the interview, she was in a managerial position at a nonprofit organization and was preparing to begin graduate school for a management degree after saving some money.

“Stan,” a senior operations analyst at a tech security company, described his motivations to be highly involved in his daughter’s life, building upon Roxanne’s premise that young people are impressionable. When asked why he feels this need, Stan explained:

My relationship with my daughter has opened me up to the idea of watching the backs of young people and educating them. Seeing my daughter grow up, I’ve noticed that kids are impressionable and innocent. And if innocence is crushed, there’s no getting it back. When you see kids and your kid grow up, you have a willingness to do more. I feel empowered to see my daughter always learning and doing new things. She’s very energetic and adventurous. Young people empower me when they see things differently, as opposed to maybe a 40-year-old who isn’t happy and thinks the world is miserable.

These self-assigned responsibilities (and seemingly the important meanings Stan associates with them) make him claim that his daughter is his primary source of empowerment in life. Stan feels more empowered to directly act in ways that increase his general sense of agency—or his ability to leverage resources toward desired goals—and to be positively influential in the lives of others, especially young people. He even developed a new set of values and core goals from parenthood. Immediately after his daughter’s birth, Stan graduated from college and left what he described as a dead-end job. During the interview, Stan planned a career switch and transitioned into the teaching profession. He credited his experience with fatherhood as the primary motivation behind this career aspiration, stating that becoming a teacher would align with his identity as a parent and give him more significant potential to make a lasting impact and legacy on other young people.

Among the 10 participants, eight explicitly connected their own professional goals to their status as a parent. In the other two interviews, the topic of child-raising was not as prominent. Across the board, participants mentioned that their diligence would have direct, positive consequences for their children, who ideally would have access to more opportunities. Here are some other examples of iterations of these ideas that surfaced in these conversations:

Now that I’m a mom, the stakes are just higher. I made a lot of mistakes as a kid—which I also want him to do—but I want him to have the safety net I didn’t. (Vanessa)

What do I do on tough days? Well, I keep a picture of my kids on my desk and that helps. My mom didn’t have a desk job so it kind of adds an extra reason to be grateful. (Nadira)

I want to continue to set an example that others can follow—not just my children but also my children’s circle of friends. (JLo)

Heightened sense of purpose and ownership of educational pursuits and nontraditional trajectories

The valuing of education and educational pursuits are typically ideals passed down from one’s guardians and parents at home (Davis-Kean, Citation2005; Kao, Citation2004). Accordingly, our sample of 10 parenting students each described the effort taken to express the importance of education to their own children, regardless of how young they are. “JLo,” a former cab dispatcher who went back to college at the age of 44—the year his interview was also conducted—mentioned that as a parent, he constantly strives to instill the value of education on his children:

My son has told me that high school kills his creativity. He hears what my daughter and I tell him about how college is so much different than high school—I just want him to get to that point. I told him that I would support him in anything he does so long as it’s positive. I learned from my father—who wasn’t necessarily the best father—to do the complete opposite from what he did. It worked out pretty well for me. I want them to find themselves. I’m not rushing them out of the house. I want them to be comfortable when they leave. I told my daughter, “If you’re pursuing your doctorate at 40, you can stay with us at home if you want to.”

My son told me he wanted to be exactly like me. Which would be a big compliment, but I thought, “No, you don’t.” He was [indefinitely] taking time off from high school, and I didn’t go to college. Who was I to tell him he couldn’t do that? But I didn’t want him to follow my path. Not educationally, at least.

In our interview, JLo also explicitly mentioned that he would keep his home open, “rent free” for his children if they need it as they transition into adulthood and continue their educational aspirations. He described that what matters most is that his son develops his own relationship to education, even if it means taking a nontraditional pathway as he did. These structured resources are beneficial to adults striving to get established, resources that parents more often provide with middle- and upper-level incomes, who often shelter their children as they look for gainful employment more often than lower-income parents (Arum & Roksa, Citation2014). In essence, more advantaged young people often have the privilege to pursue nontraditional pathways without the additional stress of wondering where their basic needs will be met. Today, JLo serves as an academic advisor in an adult education program and an adjunct instructor at a local college.

The participants in this research were identified as generally having developed a heightened sense of purpose after entering parenthood, with more clearly defined academic and professional goals in their lives. Just as Stan mentioned that his daughter helped him realize his passion for teaching, other participants similarly credited their children for assisting them to develop greater clarity about their professional ambitions. “Esquire” provides perhaps the best example of this point. Esquire had a son when he was 21 years old. He lost custody to the biological mother, who was also a young adult at the time. Esquire describes the impact that these proceedings had on his professional goals:

The reason why I came to [this elite college], the reason why I continued my education, the reason why I want to study law after this, is because of a bias in the system of law. I feel there is extreme bias in family court systems. I should have custody of my son right now. I got absolutely worked over by this sleazebag and by the courts. I got told by the courts it’s solely because I was doing too much, that I had a job while I was enrolled in college. Apparently, [the mother’s] situation, which was basically hanging out at a friend’s house all day, was better to raise a child than mine.

The experiences of these parenting students are highlighted to demonstrate instances in which having a child and becoming parents at a young age catalyzed some individuals’ academic and professional goal formation, prioritization, and visualization, to an extent. These participants learned both positive and negative parenting techniques and better conceptualized what future success for their family could look like, precisely because of the challenges they faced and the subsequent reflection on their upbringing. The stories of these 10 successful parents serve to nuance the stigmatized discourse surrounding young parents and generations to come. These reflections and subsequent rational actions exemplify how keen critical thinking benefits the agency. These instances of agency through parenthood should focus on support-oriented relationships with parenting students, which have the power to enact generational change.

Discussion: Toward more comprehensive practices

We position this qualitative research, amplifying the voice of those individuals who are often left out of assessments on their own possibilities, within interdisciplinary scholarship, including but not limited to sociology, social psychology, and adolescent/human development in the field of urban education. The findings in this small-scale study contribute to fields that include K–12 education, higher education, adult education and families, and educational policy. Our work is situated within an existing and troublesome gap in the relevant scholarship: within a rare group of asset-focused research on individuals who become parents while still school aged (Barcelos & Gubrium, Citation2014; Watson & Vogel, Citation2017), conducted to articulate how the identity of parenthood can be facilitative of students’ success. In educational contexts, there are potential consequences of the stigma surrounding the identity of parenting students (Cherrington & Breheny, Citation2005). This paper shares young parents’ positive outcomes and aspirations—not despite the challenging experiences of early parenthood but in conjunction with the newly developed identities and meaning-making within parenting experiences. Our work was positioned to locate the points of praxis that exist for young parents or recognize where there may be possibilities for leveraging action and reflection to redirect their trajectories toward liberation and advancement instead of marginalization and oppression (Freire, Citation1968).

Provided specific social and cultural support, the agency of even the most marginalized students can be fostered in the face of financial and familial duress (Carter, Citation2005; Duncan‐Andrade, Citation2007; Kundu, Citation2020). Along with parenting students’ motivation vis-à-vis being a parent, institutional resources can further support multigenerational empowerment and allow young parents to succeed further. One example is the Administration of Children’s Services (ACS), which provides child-care resources for children as young as two years old while also facilitating training and certification for parents to become educators. LaGuardia Community College in Long Island City, Queens, is an example of a two-year institution that explicitly provides support for parenting students. The Early Childhood Learning Center Program Inc. (ECLC) at LaGuardia is a high-quality, on-campus child-care program serving children ages 12 months to 12 years old. ECLC offers eight programs, including the Extended Day Program and the Saturday Program (LaGuardia Community College, Citation2020). In 2018, the US Department of Education awarded LaGuardia Community College a 1.5-million-dollar grant to expand ECLC’s parenting students’ services (LaGuardia Community College, Citation2020).

These programs acknowledge the power of education as an institutional resource to address multiple generations in the fight against poverty. Most mothers involved in the program were immigrants to the United States and had not been involved in formal education for some time. One of the graduates in the class of 2017 had not attended a school since she was 13 years old in Guyana. This very mother, commenting on the program, said, “I would have never thought that when I enrolled my son in Head Start that I would, as I say, have a head start as well” (Christ, Citation2017), highlighting the generational impacts of these social resources. Although these mothers were older than the participants of this study when they were juggling schooling and parenthood, this is an example of institutional agents’ positive role in enacting change and providing a more thorough community of understanding.

Young adulthood is a particularly vulnerable transition period with many developmental changes, in one’s physiology, network, and core identity. These years are truly “make or break” for students without safety nets who must make intentional decisions that often entail tradeoffs that other students do not have to make. Students who become young parents and display motivation and curiosity toward continuing their education should be celebrated and rewarded. We urge colleges and school enrichment programs to provide mandated and visible institutional support for these students so they not only receive the support they need to make academic strides but, perhaps more importantly, to also feel like they belong. Universities and programs also stand to benefit through offering students vibrant Early Childhood Education Centers, where innovative pedagogical practices can be both implemented and researched simultaneously. These programs foster both the achievement of the young children serviced by them as well as their parents’. Through increased inclusion, parenting students can have a better chance to enter spaces where they are traditionally underrepresented.

Concluding remarks

Our findings suggest that parenthood is a pivotal experience in the lifelong process of realizing one’s agency, even in the face of social and financial struggles. Existing external factors such as neighborhood and income are more predictive of subsequent generations of early parenthood than parenthood itself (Watson & Vogel, Citation2017); as such, institutional ambivalence need not serve as an additional obstacle for low-income parent-students of color to overcome to achieve academic and professional success. The ideology of parenthood in the United States (e.g., the topic of who exactly is fit to be a parent) continues to divide populations and communities socially, culturally, and economically to implicitly adopt deficit ideas around how young parents of color, parenting students, and low-income families value education less than others or are apathetic toward advancing their education after becoming mothers and fathers.

These defeatist positions narrow perceptions of and expectations for these individuals. Stakeholders in the lives of students who become parents should strive to locate and leverage the potential of these young people rather than to lose hope during this critical phase. In this paper, we answer a call for a better, more productive “articulation of agency” within exclusionary social institutions that characterize some students as not belonging (Emler & Reicher, Citation2004; Stanton-Salazar & Spina, Citation2000) by contributing a short yet concise discourse to the expanse of research that surrounds young parents of color. The specific phase of parenting students is notably under-researched; through this paper, we provide a rare acknowledgment of positive family outcomes to offset problematic and unproductive notions of risk that monopolize the field and often leave us without support-oriented thinking.

Though small, the 10 participants’ stories in this study serve as empirical backing behind broader issues faced by parenting students. Numerous impediments act as roadblocks both inside and outside of classroom environments that prevent low-income students from advancing in and completing their educational trajectories. At the same time, young parents often remain motivated to achieve various educational goals, undeterred and sometimes even energized by their parenting status. Focused resources from educational institutions for these students may help them reclaim their academic trajectories and professional pursuits. Given its multiple generational impacts, we should work to acknowledge that the more support there is surrounding the raising of a child, the better the long-term outcomes appear to be for the child, the parents, and the community of which they are apart.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the mothers and fathers for participating in this study and for sharing their stories and experiences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 The second author of this paper was included due to her vast knowledge and scholarship around parenting students in higher education so that our writing, and specifically the Literature Review, could be strengthened. The third author was an undergraduate student of the first author and contributed largely to the structural organization of this paper. They each made important contributions to the development of this paper.

References

- Anderson, N. S., & Nieves, L. (2020). Working to Learn: Disrupting the divide between college and career pathways for young people. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Arcand, C. (2015). How can community colleges better serve low-income single-mothers students? Lessons from the for-profit sector. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 39(12), 1187–1191. doi:10.1080/10668926.2014.985403

- Arnett, J. J. (2004). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Arum, R., & Roksa, J. (2014). Aspiring adults adrift: Tentative transitions of college graduates. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ary, D., Jacobs, L. C., Irvine, C. K. S., & Walker, D. A. (2013). Introduction to research in education. Boston, MA: Cengage.

- Aslam, R. W., Hendry, M., Booth, A., Carter, B., Charles, J. M., Craine, N., … Whitaker, R. (2017). Intervention now to eliminate repeat unintended pregnancy in teenagers (INTERUPT): A systematic review of intervention effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, and qualitative and realist synthesis of implementation factors and user engagement. BMC Medicine, 15(1), 155. 10.1186/s12916-017-0904-7

- Barcelos, C. A., & Gubrium, A. C. (2014). Reproducing stories: Strategic narratives of teen pregnancy and motherhood. Social Problems, 61(3), 466. 10.1525/sp.2014.12241

- Baum, S., & Steele, P. (2017). Who goes to graduate school and who succeeds? Urban Institute. Retrieved from https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/86981/who_goes_to_graduate_school_and_who_succeeds_0.pdf

- Bernal, E. M., Cabrera, A. F., & Terenzini, P. T. (2000). The relationship between race and socioeconomic status (SES): Implications for institutional research and admissions policies. Washington, DC: American Association of Community Colleges.

- Blackman, K. (2018). “Teen pregnancy prevention.” Teen Pregnancy Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/teen-pregnancy-prevention.aspx

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–260). Westport: Greenwood Press.

- Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (2002). The inheritance of inequality. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(3), 3–30. doi:10.1257/089533002760278686

- Bowles, S., Gintis, H., & Groves, M. O. (Eds.). (2009). Unequal chances: Family background and economic success. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Brody, G. H., Miller, G. E., Yu, T., Beach, S. R., & Chen, E. (2016). Supportive family environments ameliorate the link between racial discrimination and epigenetic aging: A replication across two longitudinal cohorts. Psychological Science, 27(4), 530–541. doi:10.1177/0956797615626703

- Carter, P. L. (2005). Keepin’ it real: School success beyond black and white. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cherrington, J., & Breheny, M. (2005). Politicizing dominant discursive constructions about teenage pregnancy: Re-locating the subject as social. Health (London, England: 1997), 9(1), 89–111. doi:10.1177/1363459305048100

- Christ, L. (2017). Early head start offers full-time school for two-year-olds by training parents to teach. Manhattan: Spectrum News NY1.

- Corcoran, J. (1998). Consequences of adolescent pregnancy/parenting. Social Work in Health Care, 27(2), 49–67. 10.1300/J010v27n02_03

- Davis-Kean, P. E. (2005). The influence of parent education and family income on child achievement: The indirect role of parental expectations and the home environment. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP, 19(2), 294–304. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.294

- Division of Reproductive Health. (2021a, August 21). About teen pregnancy. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/teenpregnancy/about/index.htm

- Division of Reproductive Health. (2021b, August 2021). Social determinants and eliminating disparities in teen pregnancy. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/teenpregnancy/about/social-determinants-disparities-teen-pregnancy.htm#health

- Duke-Benfield, A. E. (2015). Bolstering non-traditional student success: A comprehensive student aid system using financial aid, public benefits, and refundable tax credits. Center for Postsecondary and Economic Success. Retrieved from https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/publications/2017/04/bolstering-non-trad-students-formatted-paper-final.pdf

- Duncan‐Andrade, J. (2007). Gangstas, wankstas, and ridas: Defining, developing, and supporting effective teachers in urban schools. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 20(6), 617–638. doi:10.1080/09518390701630767

- Emler, N., & Reicher, S. (2004). Delinquency: Cause or consequence of social exclusion? In D. Abrams, M. A. Hogg, & J. M. Marques (Eds.), Social psychology of inclusion and exclusion (pp. 229–260). London: Psychology Press.

- Emirbayer, M., & Mische, A. (1998). What is agency? American Journal of Sociology, 103(4), 962–1023. doi:10.1086/231294

- Farb, A. F., & Margolis, A. L. (2016). The teen pregnancy prevention program (2010–2015): Synthesis of impact findings. American Journal of Public Health, 106(S1), S9–S15. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303367

- Fernandes-Alcantara, A. (2018). Federal approaches to teen pregnancy prevention. Congressional Research Service: Report R45183. Retrieved from https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R45183.html

- Fernandes-Alcantara, A. (2020). Teen pregnancy: Federal prevention programs. Congressional Research Service: Report R45183. Retrieved from https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45183

- Fordham, S., & Ogbu, J. U. (1986). Black students’ school success: Coping with the “burden of acting White. The Urban Review, 18(3), 176–206. doi:10.1007/BF01112192

- Freire, P. (1968). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Seabury Press.

- Gault, B., Reichlin, L., & Román, S. (2014). College affordability for low-income adults: Improving returns on investment for families and society. Institute for Women’s Policy Research. Retrieved from https://iwpr.org/iwpr-issues/student-parent-success-initiative/college-affordability-for-low-income-adults-improving-returns-on-investment-for-families-and-society/

- Garwood, S. K., Lara, G., Melissa, J. R., Katie, P., & Brett, D. (2015). More than poverty—teen pregnancy risk and reports of child abuse reports and neglect. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(2), 164–168. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.05.004

- Goldrick-Rab, S., Minikel-Lacocque, J., & Kinsley, P. (2011). Managing to make it: The college trajectories of traditional-age students with children. The Wisconsin Scholar Longitudinal Study. Retrieved from http://www.finaidstudy.org/documents/appam_parentpaper_wsls.pdf

- Goldthorpe, J. H. (1997). Problems of ‘meritocracy’. In A. H. Halsey, P. Lauder, P. Brown, & A. S. Wells (Eds.), Education: Culture, economy and society (pp. 663–682). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Griffee, D. T. (2005). Research Tips: Interview data collection. Journal of Developmental Education, 28(3), 36.

- Hernandez, J., & Abu Rabia, H. M. (2017). Contributing factors to older teen mothers’ academic success as very young mothers. International Journal of Higher Education, 6(4), 104–110. doi:10.5430/ijhe.v6n4p104

- Hoeve, M., Dubas, J. S., Eichelsheim, V. I., van der Laan, P. H., Smeenk, W., & Gerris, J. R. M. (2009). The relationship between parenting and delinquency: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(6), 749–775. doi:10.1007/s10802-009-9310-8

- Hoskins, D. H., & Simons, L. G. (2015). Predicting the risk of pregnancy among African American youth: Testing a social contextual model. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(4), 1163–1174. doi:10.1007/s10826-014-9925-4

- Hout, M., & Janus, A. (2011). Educational mobility in the united states since the 1930s. In G. J. Duncan & R. J. Murnane (Eds.), Whither opportunity: Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances (pp. 165–185). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Huang, C., Costeines, J., Kaufman, J., & Ayala, C. (2014). Parenting stress, social support, and depression for ethnic minority adolescent mothers: Impact on child development. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(2), 255–262. doi:10.1007/s10826-013-9807-1

- Jack, A. A. (2019). The privileged poor. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Kann, L., McManus, T., Harris, W. A., Shanklin, S. L., Flint, K. H., Hawkins, J., … Zaza, S. (2016). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries (Washington, D.C.: 2002), 65(6), 1–174.

- Kaushal, N., Magnuson, K., & Waldfogel, J. (2011). How is family income related to investments in children’s learning?. In G. J. Duncan & R. J. Murnane (Eds.), Whither opportunity: Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances (pp. 187–205). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Kenney, A. M. (1987). Teen pregnancy: An issue for schools. The Phi Delta Kappan, 68(10), 728.

- Kao, G. (2004). Parental influences on the educational outcomes of immigrant youth. International Migration Review, 38(2), 427–449. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00204.x

- Kruvelis, M. (2017). Building family-friendly campuses: Strategies to promote college success among student parents. American Council on Education. Retrieved from https://www.higheredtoday.org/2017/06/12/building-family-friendly-campuses-strategies-promote-college-success-among-student-parents/

- Kundu, A. (2017). Grit and agency: A framework for helping students in poverty to achieve academic greatness. National Youth-At-Risk Journal, 2(2), 69.

- Kundu, A. (2018). Adding a social perspective to “grit”: Investigating how disadvantaged students navigate obstacles and gain agency (Ph.D. diss.). New York University, 10573.

- Kundu, A. (2019). Understanding college “burnout” from a social perspective: Reigniting the agency of low-income racial minority strivers towards achievement. The Urban Review, 51(5), 677–698. doi:10.1007/s11256-019-00501-w

- Kundu, A. (2020). The power of student agency: Looking beyond grit to close the opportunity gap. New York: Teachers College Press.

- LaGuardia Community College. (2020, May 25). Early childhood learning center. CUNY. Retrieved from https://www.laguardia.edu/Student-Services/Child-Care/

- Langley, C., Barbee, A. P., Antle, B., Christensen, D., Archuleta, A., Sar, B. K., … Borders, K. (2015). Enhancement of reducing the risk for the 21st century: Improvement to a curriculum developed to prevent teen pregnancy and STI transmission. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 10(1), 40–69. doi:10.1080/15546128.2015.1010029

- Merton, R. K. (1948). The self-fulfilling prophecy. The Antioch Review, 8(2), 193–210. doi:10.2307/4609267

- Miller, K., Gault, B., & Thorman, A. (2011). Improving child care access to promote postsecondary success among low-income student parents. Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

- Nagaoka, J. (2016). Foundations for success. The Learning Professional, 37(6), 46.

- Neale, B., & Clayton, C. L. (2014). Young parenthood and cross-generational relationships: The perspectives of young fathers. In J. Holland, & R. Edwards (Eds.), Understanding families over time: Research and policy (pp. 69–87). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. 10.1057/9781137285089_4

- Neale, B., & Davies, L. (2016). Becoming a young breadwinner? The education, employment and training trajectories of young fathers. Social Policy and Society, 15(1), 85–98. doi:10.1017/S1474746415000512

- Nelson, B., Froehner, M., & Gault, B. (2013). College students with children are common and face many challenges in completing high education. Institute for Women’s Policy Research. Retrieved from https://iwpr.org/iwpr-issues/student-parent-success-initiative/college-students-with-children-are-common-and-face-many-challenges-in-completing-higher-education-summary/

- Noll, E., Reichlin, L., & Gault, B. (2017). College students with children: National and regional profiles. Institute for Women’s Policy Research. https://iwpr.org/iwpr-issues/student-parent-success-initiative/college-students-with-children-national-and-regional-profiles/

- Noguera, P. A. (2008). The trouble with black boys…. And other reflections on race, equity, and the future of public education. Hoboken, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

- Perez, M. (2016). The voices of student-parents and their hurdles to success in higher education (Master’s thesis). University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship,

- Perez, M., & Turner, F. (2020). Mothering graduate students of color reflect on lessons lived and learned in the academy. Women, Gender, and Families of Color, 8(2), 235–240.

- Ransaw, T. S., Gause, C. P., & Majors, R. (2018). The handbook of research on black males: Quantitative, qualitative, and multidisciplinary. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

- Robbers, M. L. P. (2009). Facilitating fatherhood: A longitudinal examination of father involvement among young minority fathers. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 26(2), 121–134. doi:10.1007/s10560-008-0157-6

- Rubin, H. J., & Rubin, I. S. (2011). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Schacter, J., & Jo, B. (2005). Learning when school is not in session: A reading summer day- camp intervention to improve the achievement of exiting first-grade students who are economically disadvantage. Journal of Research in Reading, 28(2), 158–169.

- Schumacher, R. (2013). Prepping colleges for parents: Strategies for supporting students parent success in postsecondary education. Working Paper. Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

- Shedd, C. (2015). Unequal city: Race, schools, and perceptions of injustice. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Shuger, L. (2012). Teen pregnancy and high school dropout: What communities can do to address these issues. National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy and America’s Promise Alliance.

- Simone, J. A. (2012, January 1). Addressing the marginalized student: The secondary principal’s role in eliminating deficit thinking (Ed.D. dissertation). University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, ProQuest LLC.

- Sipsma, H., Biello, K. B., Cole-Lewis, H., & Kershaw, T. (2010). Like father, like son: The intergenerational cycle of adolescent fatherhood. American Journal of Public Health, 100(3), 517–524.

- Solomon-Fears, C. (2016). Teenage pregnancy prevention: Statistics and programs. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved from https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/RS20301.pdf

- St. Rose, A., & Hill, C. (2013). Women in community colleges: Access to success. American Association of University Women. Retrieved from https://ww3.aauw.org/resource/women-in-community-colleges/

- Stanton-Salazar, R. D., & Spina, S. (2000). The network orientations of highly resilient urban minority youth: A network-analytic account of minority socialization and its educational implications. The Urban Review, 32(3), 227–261. doi:10.1023/A:1005122211864

- Stanton-Salazar, R. D. (2011). A social capital framework for the study of institutional agents and their role in the empowerment of low-status students and youth. Youth & Society, 43(3), 1066–1109.

- Stuber, J. M. (2011). Inside the college gates: How class and culture matter in higher education. Lexington Books.

- Underwood, M., Satterthwait, L. D., & Bartlett, H. P. (2010). Reflexivity and minimization of the impact of age-cohort differences between researcher and research participants. Qualitative Health Research, 20(11), 1585–1595.

- Watson, L. L., & Vogel, L. R. (2017). Educational resiliency in teen mothers. Cogent Education, 4(1), 1276009. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2016.1276009

- Wyman, P. A., Cowen, E. L., Work, W. C., & Kerley, J. H. (1993). The role of children’s future expectations in self-system functioning and adjustment to life stress: A prospective study of urban at-risk children. Development and Psychopathology, 5(4), 649–661. doi:10.1017/S0954579400006210

- Yosso, T. J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community culutral wealth. Race Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), 69–91. doi:10.1017/S0954579400006210

Appendix A

Figure A.1. This is a simplified conceptual framework diagram, based on Kundu’s (Citation2020) research, on the success of students with structural disadvantages, documented in the book The Power of Student Agency.

Appendix B

Table B.1. Participants.