Abstract

Background

Illicit drug use is common in nightlife settings and associated with various public health-related problems, making this an important arena for prevention. Purpose/objectives: To assess perceived prevalence of illicit drug use in the Stockholm nightlife setting, use of and attitudes toward illicit drugs among employees at licensed premises. Also, to make comparisons with two identical measurements from 2001 and 2007/08, and to explore potential differences related to own drug use, type of licensed premise, age or gender. Methods: Cross-sectional surveys were conducted at three time-points: 2001, 2007/08, and 2016/17, comprising employees at licensed premises in Stockholm participating in STAD’s Responsible Beverage Service training program. A total of 665 persons (mean age 28 years, 53% women) were included in the 2016/2017 measurement. Results: A majority of the respondents reported having observed patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs in the last six months, and agreed that patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs should be asked to leave licensed premises. The belief that one had observed patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs was more common among respondents who had themselves been using illicit drugs during the last year, and also among employees at nightclubs. Furthermore, comparisons with previous time-points showed a significant increase in the proportion of employees using illicit drugs. Almost half of the respondents in the youngest age group (18–24 years) reported illicit drug use during the last year. Conclusions/importance: Observation and use of illicit drugs are common among employees in the Stockholm nightlife setting and has increased significantly during the past decade.

Introduction

Illicit drug use is associated with a number of public health-related problems in both the short and long term (Bellis et al., Citation2005; Chinet et al., Citation2007; Vasica & Tennant, Citation2002), such as exposure to violence (Kurtz, Citation2012; Kurtz et al., Citation2009), sexual risk behaviors (Buttram & Kurtz, Citation2015, Citation2016; Novoa et al., Citation2005; Sterk et al., Citation2008) and developing dependence and other psychiatric problems (Cottler et al., Citation2001; Kurtz et al., Citation2011; Parrott et al., Citation2001). Recreational venues, such as nightclubs, restaurants and bars, offer people a place of entertainment and opportunity to socialize. In these settings, alcohol and illicit drugs are common and young people who frequently visit such establishments tend to display higher levels of alcohol and illicit drug use compared with the general population (EMCDDA, Citation2015). Use of illicit drugs is common among club attendees (Fernández-Calderón et al., Citation2018) and there is reason to be concerned about illicit drug use in the nightlife setting, particularly the so-called club drugs. The term club drugs refers to substances such as cocaine, ecstasy/MDMA, ketamine, and amphetamines, which are primarily used to enhance the clubbing experience (Bellis et al., Citation2002; Chinet et al., Citation2007; Miller et al., Citation2009; Parsons et al., Citation2009; Weir, Citation2000). This term also encompasses a continuous influx of new psychoactive substances, i.e. ‘designer drugs’, created by altering the chemical structures to be similar but not identical to illegal substances (German et al., Citation2014; Musselman & Hampton, Citation2014). The physiological and psychological effects of these substances vary, but include tremors, confusion, hallucinations, nausea, anxiety, respiratory depression and death (Chakraborty et al., Citation2011) and the adverse effects can be difficult to identify because of the pace at which new substances is developed (German et al., Citation2014; Musselman & Hampton, Citation2014). Young people are frequent patrons in many nightlife settings, often affected by both alcohol and other drugs. A study in San Francisco showed that a majority of participants (72%) had used alcohol while 25% tested positive for illicit drug use (Miller et al., Citation2013), and other studies indicates even higher numbers on illicit drug use (35%; Byrnes et al., Citation2019). In addition, young patrons are particularly vulnerable to testing multiple drugs, which increases the risk of adverse consequences (Kurtz et al., Citation2005, Citation2013; Owen, Citation2003). Especially electronic dance music (EDM) events are settings that attract young people who engage in high-risk behavior related to the use of alcohol and illicit drugs (Miller et al., Citation2005, Citation2009, Citation2013). In a recent online study by our research group on substance use among 1,371 EDM event attendees (age 18-34) 59% stated that they had used illicit drugs during the last year (unpublished data). Another Swedish study using biological measures at an EDM event at a cruise ship showed that the most common illicit drugs used was amphetamine, ecstasy and cannabis (Gripenberg-Abdon et al., Citation2012). International research on illicit drugs at recreational venues has mostly focused on use or related problems among patrons (Fernández-Calderón et al., Citation2018; Kurtz, Buttram, Pagano, & Surratt, Citation2017). However, bars, clubs and restaurants are also workplaces for many people, especially young people. International research indicates that the hospitality industry is a high-risk environment in that it contains the highest proportion of workers who report alcohol or illicit drug use at work or report attending work under the influence (Pidd et al., Citation2011).

The knowledge about illicit drug use among the general population in Sweden are based on survey data (CAN, Citation2017; Folkhälsomyndigheten, Citation2017). Cannabis is the most commonly used illicit substance. In 2016, the year when the present study was conducted, just over 3% of the Swedish population aged 16–64 reported that they had used cannabis during the last year, about the same proportions since 2009. There are some variations, such that cannabis use is more common among younger age groups, around 6.9% of 16-24 year olds and 7.7% percent of 25-34 year-olds reported cannabis use during the last year (Folkhälsomyndigheten, Citation2017). For the period 2013-2018 there are indications of an increase in the proportion of young people in Sweden who use cannabis (Folkhälsomyndigheten, Citation2019). The proportion of young men (age 16-29 years) who report ever use of cannabis have ranged between 26% in 2004, 20% in 2007 and 25% in 2016. Corresponding numbers among young women were 18%, 15% respectively 16% (CAN, Citation2017). The reported use of illicit substances other than cannabis indicate lower numbers. A Swedish study comprising approximately 11,000 respondents showed that 1.7% of respondents stated that they had used an illicit substance other than cannabis during the last 12 months. The proportion of users was largest in the youngest age group 17–29 years (5.1%) (Sundin et al., Citation2017). In comparison, two Swedish studies among employees at licensed premises in Stockholm showed that 26.7% (2001) respectively 18.9% (2007) of respondents reported any illicit drug use during the last year.

In Sweden, use of substances classified as narcotics, i.e. psychoactive substances that are potentially addictive, is illegal. This also includes certain medications, e.g. opioids and benzodiazepines, if used without prescription and the strict drug laws aim to prevent illicit drug use. According to the Swedish alcohol law, persons intoxicated by illicit drugs should neither be allowed to enter licensed premises nor should they be served alcohol. Owners and employees at licensed premises are required to comply with this law (Socialdepartementet, Citation2010, 1622). The total number of licensed premises in Sweden with a permanent alcohol serving permit has, according to information from the Licensing Board in Stockholm, increased gradually from 1526 in 2001 to 1615 in 2007 and to 2227 in 2016. The significant number of alcohol serving permits in Stockholm, an increase in the number of licensed premises with extended opening hours (after 01:00 am), the high availability of alcohol and illicit drugs in the premises, with the added feature of the young age of patrons and employees, make the nightlife setting an apt arena for preventive interventions. Research on substance use prevention in the nightlife setting has primarily focused on alcohol (Graham et al., Citation2004; Holder et al., Citation1993; Lang et al., Citation1998; Scherer et al., Citation2015), and in particular Responsible Beverage Service (RBS) practices, aiming to reduce underage drinking and overserving of alcohol. Evaluations have demonstrated that such interventions are sustainable and can be effective (Holder et al., Citation1993; Lang et al., Citation1998; Sannen et al., Citation2016; Scherer et al., Citation2015). In Sweden, our research team has adapted, implemented and evaluated an RBS program, the STAD-model, where the core components of this multi-component strategy are (i) community mobilization and collaboration between key stakeholders, (ii) RBS training of employees at licensed premises, and (iii) improved enforcement and policy work. The program was implemented in 1996 and findings revealed that the RBS program in Stockholm not only led to a reduction in alcohol servings to minors and alcohol-intoxicated individuals, but also to a 29% reduction in police-reported violence, which translates into a cost-savings ratio of 1:39 (Månsdotter et al., Citation2007; Wallin et al., Citation2003, Citation2005). In addition, a review on preventive interventions in drinking environments concluded that the most effective interventions are multi-component programs combining stricter enforcement, RBS training and community mobilization, i.e. the same components as in our STAD-model (Jones et al., Citation2011).

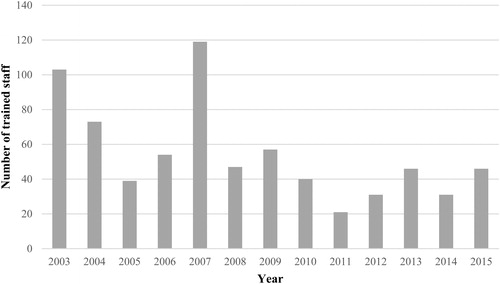

After reports from both the Police Authority and the nightlife industry regarding high rates of illicit drug use in the nightlife scene (Gripenberg, Citation2002), a survey was conducted among employees at licensed premises in Stockholm city in 2001 to study prevalence of and attitudes toward illicit drugs. The reported high rates of illicit drug use among employees (60% lifetime use, 27% last year use) raised significant concern. As a consequence, STAD developed a multi-component program named Clubs against Drugs. Similar to the RBS program, Clubs against Drugs is based on a systems approach to prevention (Holder, Citation1998, Citation2001) and aims to reduce illicit drug use among both patrons and employees in the nightlife setting (Gripenberg Abdon et al., Citation2011a; Gripenberg Abdon, Citation2012). The program includes elements such as community mobilization, adaptations of the physical environment, policy work, employee drug training, public relations work, and improved enforcement. The drug training in the Clubs against Drugs program targets all employees at licensed premises but also more specifically doormen, with the aim to train and motivate them to intervene toward patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs. All licensed premises that are a part of the Clubs against Drugs project are required to have trained doormen. The Clubs against Drugs project has been described in more detail in previous publications (Gripenberg Abdon et al., Citation2011a; Gripenberg Abdon et al., Citation2011b; Gripenberg Abdon, Citation2012). A follow-up measurement in 2007/08 showed a reduction in observations of patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs, of illicit drug use among employees and also increased rates of employee intervention toward patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs (Gripenberg Abdon et al., Citation2011b; Gripenberg Abdon, Citation2012; Gripenberg et al., Citation2007). Although the study design and the complexity of a multi-component program like Clubs against Drugs limits the possibility of conclusions on causality, it is not unlikely that the program activities were contributing to the decline in illicit drug use and the increase in employee intervention. These conclusions are also supported by the fact that evaluations of Clubs against Drugs have shown consistent results (Gripenberg Abdon et al., Citation2011b; Gripenberg Abdon, Citation2012; Gripenberg et al., Citation2007). During the years between 2001 and 2008, Clubs against Drugs was disseminated to more than 40 municipalities throughout Sweden. The dissemination and national coordination were funded by the Public Health Agency of Sweden. However, during recent years, there has been no external funding for Clubs against Drugs and, as a result, no coordination of the program in Stockholm or at a national level. As a consequence, the work within Clubs against Drugs has been less active in the recent years both at a national level and locally in Stockholm. displays differences in the amount of training delivery over the measured years. The decreased activity within Clubs against Drugs in combination with new reports from the nightlife industry and the authorities about increased illicit drug use at licensed premises, raised concerns and highlighted a need for a new assessment in 2016/17.

Collectively, the research to date demonstrates that illicit drug use is more common in the nightlife setting than among the general population and this applies to both patrons and employees. The overall objective of the present study is to assess the perceived current prevalence of observed illicit drug use by employees at licensed premises in Stockholm, current prevalence of own illicit drug use and also attitudes toward illicit drugs among employees, fifteen years after the first measurement within the Clubs against Drugs project, and to compare the results with the previous measurements conducted in 2001 and 2007/08. Secondary objectives are to explore potential differences between employees using and those not using illicit drugs, potential differences between employees working at different types of licensed premises, and also differences related to age and gender.

Materials and methods

Design

The present study is a cross-sectional survey of attitudes to and use of illicit drugs among employees at licensed premises in Stockholm, and was conducted in 2016/17. Data has also been collected at two previous time-points: in 2001 and 2007/08 from which results have been published previously (Gripenberg Abdon et al., Citation2011a, Citation2011b). The 2016/17 measurement is the main focus of this study; however, results are also compared with the two previous assessments. The same procedure (i.e. classroom setting) and the same questionnaire was used at all three assessments.

Participants and measures

Participants were employees at licensed premises in Stockholm attending STAD’s RBS training during the data collection period. The RBS training is mandatory for employees working at any licensed premise in Stockholm with a closing time after 01:00 a.m. The participants were invited to fill out an anonymous questionnaire which took about 10–15 min to complete. The questionnaire is handed out and answered early on the first day of the training, before the participants have taken any part of the content of the training. Participation was voluntary and participants gave informed consent by filling out the questionnaire after been given information about the survey. The questionnaire was developed within the project (Gripenberg Abdon et al., Citation2011a; Gripenberg, Citation2002; Gripenberg Abdon, Citation2012) and comprised a total of 27 questions (see Appendix). Items covered four sections: 1) demographic data on gender, age, occupation, and work experience, 2) attitudes toward illicit drugs, e.g.” Do you think it should be illegal to be affected by illicit drugs” with response options “yes”, “no” and “do not know”, 3) observed illicit drug use among patrons, e.g. “Have you seen anyone being offered illicit drug at a licensed premise in Stockholm”, with six response options ranging from “no” to “yes, almost every night”, and 4) own illicit drug use, asking respondents to state whether they had used different types of illicit drugs such as cannabis, cocaine, and ecstasy.

Analyses

Data were analyzed to describe observations and use of illicit drugs, and the χ2 test was used to investigate potential differences between the measurement years, and between gender and age groups (p < 0.05). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to test mean differences in participant age and number of years of work experience in the hospitality industry. All analyses were conducted using SPSS 23.0.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (Dnr 2007/504-31).

Results

Sample characteristics

Characteristics of the 2001 and 2007/08 samples have been published previously (Gripenberg Abdon et al., Citation2011a), and comprised 446 and 677 employees, respectively, from licensed premises in Stockholm. The present sample comprised 665 employees from about 160 licensed premises in Stockholm municipality. Among the respondents, 47.2% (n = 310) were men and 52.8% (n = 347) were women, the mean age was 28.2 years (SD = 8.7) and the mean work experience at licensed premises was 7.1 years (SD = 7.1). There was no difference in mean age compared with the previous time-points (p = 0.212), but a significant difference in years of work experience (8.2, 8.7 vs. 7.1) (p < 0.001). Several occupational categories were reported and 43.4% (n = 287) reported multiple categories. More than half (52.6%, n = 348) were waiting staff, while 43.5% (n = 288) were bartenders, 17.1% (n = 113) head waiters, 24.8% (n = 164) restaurant managers, 3% (n = 20) owners, 3% (n = 20) door staff, and 0.8% (n = 5) security guards. The employees worked at different types of licensed premises, most commonly restaurants (32.2%, n = 209), bars/pubs (31.9%, n = 207), hotels (19.3%, n = 125) and night clubs (8.9%, n = 58). One respondent (0.2%) reported working at a student pub while 7.6% (n = 49) reported working at another type of premise. As at the previous time-points, all who were invited to participate consented (no external drop-out). Missing data on specific items were treated as drop-out (no imputation) and ranged from 0.5% to 14.1% (n = 3–94). The drop-out rate was highest regarding own illicit drug use. displays demographic comparisons between the samples.

Table 1. Demographic comparisons between the samples.

Observed illicit drug use among patrons

The majority of respondents (78.4%, n = 519) reported that they believed they had observed patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs at licensed premises in Stockholm in the last six months, and 21.5% (n = 142) believed they had observed patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs in the last week. Almost half of respondents (47.6%, n = 314) reported having observed an illicit drug-offer and 43.2% (n = 285) reported having observed someone take illicit drugs at licensed premises in Stockholm in the last year.

Attitudes and behavioral intention

Almost three quarters of respondents (71.3%, n = 471) agreed that patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs should always be asked to leave the licensed premises. In addition, 53.7% of respondents (n = 350) agreed that it should be illegal to be under the influence of illicit drugs. Just over three quarters of respondents (77.9%, n = 509) did not think illicit drugs should be legal, while 10.6% (n = 69) thought that illicit drugs should be legal, like tobacco and alcohol. Although the majority of respondents thought they had observed patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs and believed that they should be asked to leave the premises, 56.2% (n = 369) had never asked a patron intoxicated by illicit drugs to leave the licensed premises where they worked.

Own illicit drug use

Nearly thirty-five percent of respondents (34.8%, n = 219) reported own illicit drug use in the last year, while 60.8% (n = 383) reported ever use of illicit drugs. The most commonly used drugs were cannabis (58.7%, n = 367), cocaine (31.4%, n = 187), and ecstasy (24.4%, n = 145).

Differences in illicit drug use between sex and age groups

There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of women (55.9%, n = 189) and men (51.1%, n = 157) who responded that intoxication by illicit drugs should be illegal (χ2 = 1.476, p = 0.224). However, a significantly greater proportion of men considered that illicit drugs should be legal in the same way as alcohol and tobacco (13.3% (n = 41) vs. 8% (n = 27), χ2 = 4.849, p = 0.028). No significant gender differences were found in terms of own use, neither for last year use (33.0% (n = 109) vs. 37.0% (n = 108), χ2 = 1.067, p = 0.302), nor for ever having used illicit drugs (61.8% (n = 204) vs. 59.9% (n = 175), χ2 = 0.232, p = 0.630).

As is shown in , last year illicit drug use was most common in the younger age group (18–24 years); almost half of the respondents under 25 years of age reported use of illicit drugs in the last year.

Table 2. Rates of reported lifetime drug use and last year drug use, by age.

Comparisons between employees using and those not using illicit drugs

shows that a significantly higher proportion of respondents who reported own illicit drug use in the last year reported believing that they had observed patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs or having seen an illicit drug offer or drug intake at licensed premises in Stockholm, compared with respondents who did not use illicit drugs. Furthermore, compared with respondents who had never used illicit drugs, a significantly higher proportion of the illicit drug users responded that illicit drugs should be legal in the same way as tobacco and alcohol, while a significantly lower proportion stated that patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs should always be removed from licensed premises. In addition, significantly fewer of the drug-using respondents thought it should be illegal to be under the influence of illicit drugs.

Table 3. Comparisons between last year drug users and non-drug users, attitudes and observations.

Comparisons between employees working at different types of licensed premises

As is shown in there was no statistically significant difference between respondents working at different types of licensed premises regarding the proportion who thought that patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs should always be asked to leave the licensed premises, the proportion who thought it should be illegal to be intoxicated by illicit drugs or the proportion who thought illicit drugs should be legal in the same way as alcohol and tobacco. However, compared to respondents working at nightclubs a significantly larger proportion of respondents working at hotels reported that they would contact the police if observing a drug-intake where they work. Also, having observed a drug intake at a licensed premise during the last year and having observed patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs during the last six months was reported by a larger proportion of respondents working at nightclubs, compared to respondents working at hotels. Believing to have observed a drug offer at a licensed premise during the last year was reported by a larger proportion of respondents working at bars/pubs and at nightclubs, compared to respondents working at hotels.

Table 4. Comparisons regarding attitudes and behavioral intentions among employees at different types of licensed premises (percentage distribution).

As is displayed in , lifetime use of illicit drugs was reported by a larger proportion of respondents working at bars/pubs and restaurants, compared to respondents working at hotels. The difference between respondents at different types of licensed premises regarding last year use of illicit drugs was not statistically significant.

Table 5. Comparisons regarding illicit drug use (lifetime and last year) among employees at different types of licensed premises (percentage distribution).

Comparisons over the measurement years

As shown in , the proportion of respondents who reported they would call the police if they saw a patron intoxicated by illicit drugs and who stated that patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs should always be removed from licensed premises was significantly lower at the measurement in 2016/17 compared with in 2007/08. In addition, a significantly lower proportion of respondents reported that they thought it should be illegal to be under the influence of drugs. Also, in comparison with the first measurement, a significantly larger proportion of respondents in the most recent survey reported having seen someone being offered illicit drugs at licensed premises in the last year.

Table 6. Comparisons over time, attitudes and behavioral intentions among employees (percentage distribution).

displays comparisons over the measurement years, in lifetime illicit drug use, last year illicit drug use and by type of illicit drug. Compared with the first measurement in 2001, in 2016/17 there was a significantly larger proportion of respondents who reported that they had ever used cannabis, cocaine, ecstasy, or medical drugs without prescription.

Table 7. Comparisons over time, proportion (%) of employees reporting lifetime use of illicit drugs (and by substance).

Discussion

Results from the present study demonstrated that according to self-reported observations from staff at licensed premises illicit drugs are common in the nightlife setting in Stockholm, and has also increased since the previous measurement in 2007/08. A majority of the respondents reported that they believed they had observed patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs and almost half of the respondents reported having observed a drug-offer or a drug intake in the past year. While the assessment in 2007/08 showed significant reductions in illicit drug use compared with 2001, the results from the present measurement (collected 2016/17) indicate that employee observations of illicit drug use among patrons and own illicit drug use among employees has comparatively and significantly increased at licensed premises in Stockholm. Thus, the results show a deteriorating illicit drug situation, which is in line with the indications that STAD received from the nightlife industry and authorities before the study was conducted. Several factors could be contributing to this; on a societal level one factor contributing to increased use of illicit drugs could be changes in the price of illicit drugs. Prices for drugs have been monitored in Sweden since 1988, and since (mostly before 2000) the prices have dropped significantly. Over the last ten years the prices have been more stable. The price for cannabis has increased somewhat which is probably due to an increase in the THC level (CAN, Citation2017). Other factors are increased availability and opportunity to anonymously obtain illicit drugs via the Internet (Christin, Citation2013; Van Buskirk et al., Citation2017). An increased number of confiscations of drugs by the Police Authority and Swedish Customs could also be a reflection of increased availability and use of illicit drugs in general (Folkhälsomyndigheten, Citation2019). Another factor is the growing evidence of changes in attitudes among today’s youth toward illicit drug use, especially cannabis. A recent Swedish survey indicate changes in attitudes toward the risks involved with using cannabis (Englund & Svensson, Citation2020). In addition, international research indicates that young people’s attitudes toward cannabis is getting more permissive over time (Schmidt et al., Citation2016) and also that low levels of perceived risk and negative consequences is associated with personal use of the drug (Barrett & Bradley, Citation2016). Research has also shown that changes in attitudes, i.e. degree of perceived risk of harm, is associated with behavioral changes related to cannabis use (Miech et al., Citation2017; Pilkington, Citation2007; Schulenberg et al., Citation2017). In addition, in 2015 there was a reorganizations within the Police Authority at a national as well as regional level (Regeringskansliet [Government offices], 2014), which has led to a reduced presence of the Police in Stockholm's nightlife settings. After the reorganization, there were also decreases in the number of employees at the Police Authority (SVT Sveriges Television, Citation2018). Furthermore, during recent years there has been no funding allocated for coordinating Clubs against Drugs and program activities have consequently decreased. Although the study design does not allow for conclusions about causality, the decline in focused activities within the Clubs against Drugs program might also have contributed to the perceived increase of illicit drugs in the nightlife setting of Stockholm. Although there are some indications that the use of cannabis has increased in Sweden over the past years and survey data also suggest an increase in the use of cocaine and ecstasy, the increase of illicit drugs in the nightlife setting does not seem to correspond to a similar increase at the community level. The population based surveys indicate small changes and illicit drug use among the general population is still low (CAN, Citation2017; Folkhälsomyndigheten, Citation2017; Sundin et al., Citation2017).

Studies on prevention of illicit drugs in the nightlife setting is often focused on investigating drug consumption patterns, drug-related problems or brief interventions among patrons (Fernández-Calderón et al., Citation2018; Kurtz et al., Citation2017). Generally, brief interventions have not been shown to be as effective with illicit drugs as it has been in the prevention of alcohol use (Arnaud et al., Citation2016; White et al., Citation2015). A randomized trial comparing motivational enhancement therapy to information only intervention indicated reductions in ecstasy use in both conditions (Norberg et al., Citation2014) and research on dissemination of educational materials have yielded mixed results regarding attitudes toward illicit drugs (Whittingham et al., Citation2009). However, there is research indicating that health messages given by peers might be promising (Silins et al., Citation2013). The research on preventive interventions has to date focused primarily on adaptations in the physical environment at licensed premises and on harm-reduction strategies, e.g. drug test services and information on illicit drugs (Sannen et al., Citation2016) which aim to reduce drug-related problems and harm (Bellis et al., Citation2002; Butler, Citation2005; Drugs & Public Policy Group, Citation2010; Weir, Citation2000). A recent review of the evidence for the effectiveness of digital interventions targeting young adults indicate that digital interventions may produce a modest reduction in harm from illicit substance misuse. However, more research is needed on interventions that target illicit substances only (Dick et al., Citation2019).

Studies on illicit drug use among employees at licensed premises are scarce. However, a study at licensed premises in Norway shows similar patterns to the present study, but with differences in the magnitude of use (Buvik et al., Citation2019). Almost half of the employees in the Norwegian study reported own illicit drug use (Buvik et al., Citation2019) while the corresponding proportion in the present study was 61%. Both studies demonstrated that illicit drug use is most prevalent in the younger age group and that the most common drugs used were cannabis, cocaine, ecstasy, and amphetamine. The Norwegian study showed that half of the employees aged 18–25-year had ever used illicit drugs and one fifth had used in the last year (Buvik et al., Citation2019). The corresponding figures in the present study were even higher (67% and 47%, respectively), thus indicating that illicit drug use might be more common among employees at licensed premises in Stockholm. In addition, a Norwegian study of illicit drug use among patrons in the nightlife setting also showed high levels of use (Nordfjaern et al., Citation2016), which is in line with other studies (Betzler et al., Citation2019; Gripenberg-Abdon et al., Citation2012; Miller et al., Citation2013; Nordfjaern et al., Citation2016). Studies of illicit drug use in the general population indicate lower numbers, e.g. a Swedish study comprising 15,000 persons, shows that in the age group between 17 and 19 years, a total of 6% reported illicit drug use in the last year. In the same study, among individuals between 20 and 29 years, the figure was the same for women (6%) and was 14% among men (Ramstedt et al., Citation2014). EMCDDA demonstrated that among 15- to 34-year-olds across Europe, the prevalence of last year illicit drug use varied between 1.8% and 14% depending on the substance, with large differences between countries (EMCDDA, Citation2018). In contrast, a study of young people in drinking environments in nine European countries found that cannabis use was reported by 73.8%, cocaine use by 30.4%, and ecstasy use by 28.7% (ever) (Bellis et al., Citation2008). A study in San Francisco using biological measures showed that 25% tested positive for illicit drug use (Miller et al., Citation2013). Collectively, the research to date demonstrates that illicit drug use is more common in the nightlife setting than among the general population and this applies to both patrons and employees. There are several possible explanations to these findings; licensed premises are venues where both alcohol and illicit drugs are common (Gripenberg, Citation2002; Norstrom et al., Citation2012; Wallin et al., Citation2005), which exposes employees at licensed premises to illicit drugs in their work environment. Research has shown that the hospitality industry contains the highest proportion of workers who report attending work under the influence or use alcohol or illicit drug use at work (Pidd et al., Citation2011). This, in combination with a work situation which often includes late nights and long work hours, makes licensed premises an important arena for preventive interventions, especially given the high turnover and relatively young age of employees. Young adults are also a group that are generally difficult to reach with preventive interventions (Ramstedt et al., Citation2013) and our current results reinforce the importance of targeting this age group, in particular in these high risk work environments.

It should also be mentioned that a significantly higher proportion of employees who had themselves been using illicit drugs also reported having observed patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs. Furthermore, a significantly higher proportion of employees who had used illicit drugs also responded that illicit drugs should be legal in the same way as tobacco and alcohol while significantly fewer thought it should be illegal to be under the influence of illicit drugs. This indicates that employees who have been using illicit drugs themselves are more aware of drugs in their surroundings and also, that they are more liberal in their attitudes toward illicit drugs. This is important to keep in mind when implementing preventive strategies in this arena. Another aspect to keep in mind is that employees at different types of licensed premises may have varying attitudes and varying degrees of experience with illicit drugs. Previous research indicates that illicit drug use is more common among patrons at nightclubs, compared to bars and pubs (Coomber et al., Citation2017). This is in line with the results in the present study, showing that there was a larger proportion of employees at nightclubs who had seen someone take drugs at licensed premises during the past year and also, that they believed they had seen patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs during the last 6 months. In addition, a greater proportion of employees at bars/pubs and at nightclubs, compared to employees working at hotels, thought they had seen a drug-offer at licensed premises during the last year. This could be due to illicit drugs being less prevalent at hotel bars, another explanation could be that employees at different types of premises are more or less aware of illicit drugs in their surroundings. It should also be mentioned that a greater proportion of employees at bars/pubs and at restaurants reported own experience of having ever used of illicit drugs compared to employees at hotels. In addition, a larger proportion of employees at hotels, compared to employees at nightclubs, reported that they would contact the police if they saw someone taking illicit drugs where they work. Thus, while the hotel employees seem to be most likely to contact the police if they detect drug use, it also seems that they are less likely to have seen a drug-offer at licensed premises during the last year. These differences between occupational groups are important to consider when planning interventions and employee trainings.

Study limitations

One concern could be that the STAD’s RBS training raises a general awareness of illicit drug use among employees at licensed premises. That is also part of the purpose of the training, that employees should gain more knowledge and become more attentive. However, it should be pointed out that the questionnaire is answered before the participants have taken any part of the training content. Furthermore, not only does the result show an increase in the proportion of observed patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs, it also shows a statistically significant increase in reports of own use. These reports of own illicit drug use are in line with other studies in the nightlife setting also indicating high levels of illicit drug use among both employees and patrons, especially in the younger age group (Buvik et al., Citation2019; Nordfjaern et al., Citation2016). Study respondents were not randomly selected, but consisted of all employees at licensed premises who participated in STAD’s RBS training. This limits the possibility of generalizing the results to all restaurants, bars, and clubs in Stockholm and in Sweden. However, Stockholm’s city guidelines state that all licensed premises with serving times after 01:00 a.m. must have their employees undergo STAD’s RBS training. This makes it reasonable to assume that the results are likely to provide a relatively accurate representation of the drug situation at licensed premises in Stockholm with late opening hours. In addition, it is difficult to select a random sample of employees at licensed premises, due to high turnover of employees. It should also be mentioned that the reported observations of intoxication involve a subjective assessment and it is possible that employees may mistake what kind of intoxication they observe (by alcohol or illicit drugs). However, it is likely that distinguishing alcohol intoxication from intoxication by illicit drugs would be equally difficult over the measurement years, and thus not affect the changes over time. Some of the respondents chose not to answer certain items, which is common in research involving surveys. The internal drop-out rate was generally low; however, the items related to own illicit drug use had higher drop-out rates. It should be mentioned that the present study has no external drop-out, i.e. everyone chose to answer the questionnaire. Furthermore, the data compared from the three time-points are cross-sectional, which excludes the possibilities to make assumptions about causality. The data are based on self-reports, which makes some under-reporting likely, especially regarding own illicit drug use (Gripenberg-Abdon et al., Citation2012; Johnson et al., Citation2009). However, respondents were asked to sit apart and the survey did not ask for any personal information, to ensure anonymity.

The current survey, within the framework of the Clubs against Drugs project, demonstrated that illicit drugs are common in the nightlife setting in Stockholm and, compared with the measurement in 2007/08, shows an increased proportion of employees reporting own illicit drug use. The present proportion of illicit drug use was also higher compared with 2001, with respect to last year illicit drug use and lifetime use of cocaine and ecstasy. Furthermore, the finding that illicit drug use is most common among employees between 18 and 24 years is indicative of a risk group working in these professional settings. These increases in illicit drug use among patrons and employees show that the drug situation in the nightlife setting in Stockholm has deteriorated since the last measurement in 2007/08, indicating that the drug prevention work in the nightlife setting needs to be strengthened. Clubs against Drugs is a program that has previously shown to be an effective part of such work and our results emphasize the importance of maintaining such initiatives. At present, there is no organization responsible for managing this work and there is a clear need for national coordination of Clubs against Drugs. Preventive work must be carried out continuously and requires long-term funding to ensure sustainability and guarantee effectiveness.

Data statement section

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Center for Psychiatry Research, a collaboration between the Karolinska Institute and Stockholm County Council, but restrictions apply to their availability, as they were used under ethical permission for the current study, and so are not publicly available. However, data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from the Center for Psychiatry Research.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the course coordinators at STAD’s RBS training for assistance with data collection.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arnaud, N., Baldus, C., Elgan, T. H., De Paepe, N., Tonnesen, H., Csemy, L., & Thomasius, R. (2016). Effectiveness of a web-based screening and fully automated brief motivational intervention for adolescent substance use: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(5), e103. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4643

- Barrett, P., & Bradley, C. (2016). Attitudes and perceived risk of cannabis use in Irish adolescents. Irish Journal of Medical Science (1971-), 185(3), 643–647. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-015-1325-2

- Bellis, M. A., H, K., McVeigh, J., Thomson, R., & Luke, C. (2005). Effects of nightlife activity on health. Nursing Standard, 19(30), 63–71.

- Bellis, M. A., Hughes, K., & Lowey, H. (2002). Healthy nightclubs and recreational substance use - From a harm minimisation to a healthy settings approach. Addictive Behaviors, 27(6), 1025–1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4603(02)00271-X

- Bellis, M. A., Hughes, K., Calafat, A., Juan, M., Ramon, A., Rodriguez, J. A., Mendes, F., Schnitzer, S., & Phillips-Howard, P. (2008). Sexual uses of alcohol and drugs and the associated health risks: A cross sectional study of young people in nine European cities. BMC Public Health, 8(1), 155–155. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-155

- Betzler, F., Ernst, F., Helbig, J., Viohl, L., Roediger, L., Meister, S., Romanczuk-Seiferth, N., Heinz, A., Ströhle, A., & Köhler, S. (2019). Substance Use and Prevention Programs in Berlin's Party Scene: Results of the SuPrA-Study. European Addiction Research, 25(6), 283–292. https://doi.org/10.1159/000501310

- Butler, S. (2005). The prevention of substance use, risk and harm in Australia: A review of the evidence. Drugs-Education Prevention and Policy, 12(3), 247–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687630500070037

- Buttram, M. E., & Kurtz, S. P. (2015). Characteristics associated with group sex participation among men and women in the club drug scene. Sexual Health, 12(6), 560–562. https://doi.org/10.1071/Sh15071

- Buttram, M. E., & Kurtz, S. P. (2016). Alternate routes of administration among prescription opioid misusers and associations with sexual HIV transmission risk behaviors. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 48(3), 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2016.1187319

- Buvik, K., Bye, E. K., & Gripenberg, J. (2019). Alcohol and drug use among staff at licensed premises in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 47(4), 393–399. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494818761417

- Byrnes, H. F., Miller, B. A., Bourdeau, B., & Johnson, M. B. (2019). Impact of group cohesion among drinking groups at nightclubs on risk from alcohol and other drug use. Journal of Drug Issues, 49(4), 668–679. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022042619859257

- CAN (2017). Drogutvecklingen i Sverige 2017. [The Drug development in Sweden 2017] [In Swedish]. Centralförbundet för alkohol- och narkotikaupplysning, CAN, Rapport 164. [The Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs].

- Chakraborty, K., Neogi, R., & Basu, D. (2011). Club drugs: Review of the 'rave' with a note of concern for the Indian scenario. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 133(6), 594–604.

- Chinet, L., Stephan, P., Zobel, F., & Halfon, O. (2007). Party drug use in techno nights: A field survey among French-speaking Swiss attendees. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior, 86(2), 284–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2006.07.025

- Christin, N. (2013). Traveling the Silk Road: A measurement analysis of a large anonymous online marketplace. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on World Wide Web ACM (pp. 213–224).

- Coomber, K., Droste, N., Pennay, A., Mayshak, R., Martino, F., & Miller, P. G. (2017). Trends across the night in patronage, intoxication, and licensed venue characteristics in five Australian cities. Substance Use & Misuse, 52(9), 1185–1195. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2017.1302955

- Cottler, L. B., Womack, S. B., Compton, W. M., & Ben-Abdallah, A. (2001). Ecstasy abuse and dependence among adolescents and young adults: Applicability and reliability of DSM-IV criteria. Human Psychopharmacology, 16(8), 599–606. https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.343

- Dick, S., Whelan, E., Davoren, M. P., Dockray, S., Heavin, C., Linehan, C., & Byrne, M. (2019). A systematic review of the effectiveness of digital interventions for illicit substance misuse harm reduction in third-level students. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1244. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7583-6

- Drugs & Public Policy Group. (2010). Drug policy and the public good: A summary of the book. Addiction, 105(7), 1137–1145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03049.x

- EMCDDA (2015). European drug report 2015: Trends and development. EMCDDA.

- EMCDDA (2018). European drug report 2018: Trends and developments. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Englund, A., & Svensson, J. (2020). Ungas riskuppfattning och bruk– hänger det ihop? Substansanvändning och riskuppfattning bland skolungdomar i de svenska ESPAD undersökningarna 1995 – 2019. [Young people's risk perception and use - is it related? Substance use and risk perception among schoolchildren in the Swedish ESPAD surveys 1995 - 2019][In Swedish] Centralförbundet för alkohol- och narkotikaupplysning, CAN, Fokusrapport 06. [The Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs].

- Fernández-Calderón, F., Cleland, C. M., & Palamar, J. J. (2018). Polysubstance use profiles among electronic dance music party attendees in New York City and their relation to use of new psychoactive substances. Addictive Behaviors, 78, 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.11.004

- Folkhälsomyndigheten (2017). Den svenska narkotikasituationen - en översikt över rapporteringen till EU:s narkotikabyrå. [The Swedish drug situation - an overview of reporting to the EU Drugs Agency] [in Swedish]. The Public Health Agency of Sweden:

- Folkhälsomyndigheten (2019). Den svenska narkotikasituationen. [The Swedish drug situation] [in Swedish]. The Public Health Agency of Sweden.

- German, C. L., Fleckenstein, A. E., & Hanson, G. R. (2014). Bath salts and synthetic cathinones: An emerging designer drug phenomenon. Life Sciences, 97(1), 2–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2013.07.023

- Graham, K., Osgood, D. W., Zibrowski, E., Purcell, J., Gliksman, L., Leonard, K., Pernanen, K., Saltz, R. F., & Toomey, T. L. (2004). The effect of the Safer Bars programme on physical aggression in bars: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Rev, 23(1), 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/09595230410001645538

- Gripenberg Abdon, J. (2012). Drug use at licensed premises- prevalence and prevention. Karolinska Institutet Doctoral thesis. Department of Public Health Sciences.

- Gripenberg Abdon, J., Wallin, E., & Andreasson, S. (2011a). The "Clubs against Drugs" program in Stockholm, Sweden: Two cross-sectional surveys examining drug use among staff at licensed premises. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 6, 2 https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-6-2

- Gripenberg Abdon, J., Wallin, E., & Andreasson, S. (2011b). Long-term effects of a community-based intervention: 5-year follow-up of 'Clubs against Drugs'. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 106(11), 1997–2004. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03573.x

- Gripenberg, J. (2002). Droger på krogen. En kartläggning av narkotikasituationen på Stockholms krogar [Drugs at clubs. A study of the drug situation at clubs in Stockholm][In Swedish] Stockholm: Stockholm Prevents Alcohol and Drug Problems (STAD); 2002

- Gripenberg, J., Wallin, E., & Andreasson, S. (2007). Effects of a community-based drug use prevention program targeting licensed premises. Subst Use Misuse, 42(12-13), 1883–1898. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080701532916

- Gripenberg-Abdon, J., Elgán, T. H., Wallin, E., Shaafati, M., Beck, O., & Andréasson, S. (2012). Measuring substance use in the club setting: A feasibility study using biochemical markers. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 7(1), 7https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597x-7-7

- Holder, H. D. (1998). Alcohol and the community: A systems approach to prevention. Cambridge University press.

- Holder, H. D. (2001). Prevention of alcohol problems in the 21st century: Challenges and opportunities. The American Journal on Addictions, 10(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/105504901750160402

- Holder, H. D., Janes, K., Mosher, J., Saltz, R., Spurr, S., & Wagenaar, A. C. (1993). Alcoholic Beverage Server Liability and the Reduction of Alcohol-Involved Problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 54(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.1993.54.23

- Johnson, M. B., Voas, R. A., Miller, B. A., & Holder, H. D. (2009). Predicting Drug Use at Electronic Music Dance Events: Self-Reports and Biological Measurement. Evaluation Review, 33(3), 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841x09333253

- Jones, L., Hughes, K., Atkinson, A. M., & Bellis, M. A. (2011). Reducing harm in drinking environments: A systematic review of effective approaches. Health & Place, 17(2), 508–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.12.006

- Kurtz, S. P. (2012). Arrest histories, victimization, substance use, and sexual risk behaviors among young adults in Miami's club scene. In Y. F. T. B. Sanders, & B. Deeds (Eds.), (Ed.), Crime, HIV, and health: Intersections of criminal justice and public health concerns (pp. 151–166). Springer.

- Kurtz, S. P., Buttram, M. E., Pagano, M. E., & Surratt, H. L. (2017). A randomized trial of brief assessment interventions for young adults who use drugs in the club scene. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 78, 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2017.05.008

- Kurtz, S. P., Inciardi, J. A., Surratt, H. L., & Cottler, L. (2005). Prescription drug abuse among ecstasy users in Miami. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 24(4), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1300/J069v24n04_01

- Kurtz, S. P., Inciardi, J., & Pujals, E. (2009). Criminal activity among young adults in the club scene. Law Enforcement Executive Forum, 9(2), 47–59.

- Kurtz, S. P., Surratt, H. L., Buttram, M. E., Levi-Minzi, M. A., & Chen, M. X. (2013). Interview as intervention: The case of young adult multidrug users in the club scene. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 44(3), 301–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2012.08.004

- Kurtz, S. P., Surratt, H. L., Levi-Minzi, M. A., & Mooss, A. (2011). Benzodiazepine dependence among multidrug users in the club scene. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 119(1-2), 99–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.036

- Lang, E., Stockwell, T. I. M., Rydon, P., & Beel, A. (1998). Can training bar staff in responsible serving practices reduce alcohol-related harm? Drug and Alcohol Review, 17(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/09595239800187581

- Månsdotter, A. M., Rydberg, M. K., Wallin, E., Lindholm, L. A., & Andréasson, S. (2007). A cost-effectiveness analysis of alcohol prevention targeting licensed premises. European Journal of Public Health, 17(6), 618–623. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckm017

- Miech, R., Johnston, L & O’Malley, P. M. (2017). Prevalence and Attitudes Regarding Marijuana Use Among Adolescents Over the Past Decade. Pediatrics, 140(6), e20170982. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0982

- Miller, B. A., Byrnes, H. F., Branner, A. C., Voas, R., & Johnson, M. B. (2013). Assessment of Club patrons' alcohol and drug use: the use of biological markers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 45(5), 637–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.014

- Miller, B. A., Furr-Holden, C. D., Voas, R. B., & Bright, K. (2005). Emerging Adults' Substance use and Risky Behaviors in Club Settings. Journal of Drug Issues, 35(2), 357–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204260503500207

- Miller, B. A., Furr-Holden, D., Johnson, M. B., Holder, H., Voas, R., & Keagy, C. (2009). Biological Markers of Drug Use in the Club Setting. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 70(2), 261–268. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2009.70.261

- Musselman, M. E., & Hampton, J. P. (2014). "Not for human consumption": a review of emerging designer drugs. Pharmacotherapy, 34(7), 745–757. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.1424

- Norberg, M. M., Hides, L., Olivier, J., Khawar, L., McKetin, R., & Copeland, J. (2014). Brief Interventions to Reduce Ecstasy Use: A Multi-Site Randomized Controlled Trial. Behavior Therapy, 45(6), 745–759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2014.05.006

- Nordfjaern, T., Bretteville-Jensen, A. L., Edland-Gryt, M., & Gripenberg, J. (2016). Risky substance use among young adults in the nightlife arena: An underused setting for risk-reducing interventions? Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 44(7), 638–645. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494816665775

- Norstrom, T., Sundin, E., Muller, D., & Leifman, H. (2012). Hazardous drinking among restaurant workers. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 40(7), 591–595. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494812456634

- Novoa, R. A., Ompad, D. C., Wu, Y. F., Vlahov, D., & Galea, S. (2005). Ecstasy use and its association with sexual behaviors among drug users in New York City. Journal of Community Health, 30(5), 331–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-005-5515-0

- Owen, F. (2003). Clubland: The fabulous rise and murderous fall of club culture. St. Martin´s Press.

- Parrott, A. C., Milani, R. M., Parmar, R., & Turner, J. J. D. (2001). Recreational ecstasy/MDMA and other drug users from the UK and Italy: Psychiatric symptoms and psychobiological problems. Psychopharmacology (Psychopharmacology), 159(1), 77–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002130100897

- Parsons, J. T., Grov, C., & Kelly, B. C. (2009). Club Drug Use and Dependence Among Young Adults Recruited Through Time-Space Sampling. Public Health Reports (Washington, D.C. : 1974)), 124(2), 246–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335490912400212

- Pidd, K., Roche, A. M., & Buisman-Pijlman, F. (2011). Intoxicated workers: Findings from a national Australian survey. Addiction (Abingdon, England)), 106(9), 1623–1633. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03462.x

- Pilkington, H. (2007). Beyond 'peer pressure': Rethinking drug use and 'youth culture'. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 18(3), 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.08.003

- Ramstedt, M., Lindell, A., & Raninen, J. (2013). Tal om alkohol 2012 – en statistisk årsrapport från monitorprojektet [Talk about alcohol 2012 - a statistical annual report from the monitoring project] [in Swedish]. Stockholm: SoRAD.

- Ramstedt, M., Sundin, E., Landberg, J., & Raninen, J. (2014). ANDT-bruket och dess negativa konsekvenser i den svenska befolkningen 2013 - en studie med fokus på missbruk och beroende samt problem för andra än brukaren relaterat till alkohol, narkotika, dopning och tobak. [ANDT use and its negative consequences in the Swedish population in 2013 - a study focusing on addiction and harm to others related to alcohol, drugs, doping and tobacco] [in Swedish]

- Regeringskansliet [Government offices] (2014). Regeringens proposition - En ny organisation för polisen [Government Bill - A new organization for the Police Authority]. 2013/14:110. [in Swedish].

- Sannen, A., Krusche, L., Hughes, K., Burkhart, G., & van Hasselt, N. (2016). Responding to drug and alcohol use and related problems in nightlife settings Retrieved from Healthy nightlife toolbox:

- Scherer, M., Fell, J. C., Thomas, S., & Voas, R. B. (2015). Effects of Dram Shop, Responsible Beverage Service Training, and State Alcohol Control Laws on Underage Drinking Driver Fatal Crash Ratios. Traffic Injury Prevention, 16(sup2), S59–S65. https://doi.org/10.1080/15389588.2015.1064909

- Schmidt, L. A., Jacobs, L. M., & Spetz, J. (2016). Young People's More Permissive Views About Marijuana: Local Impact of State Laws or National Trend? American Journal of Public Health, 106(8), 1498–1503. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303153

- Schulenberg, J. E., Johnston, L. D., O'Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., Miech, R. A., & Patrick, M. E. (2017). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2016: Volume II, college students and adults ages 19-55. Retrieved from

- Silins, E., B, A., Simpson, M., Dillon., & Copeland, J. (2013). Does Peer-Delivered Information at Music Events Reduce Ecstasy and Methamphetamine Use at Three Month Follow-Up? Findings from a Quasi-Experiment across Three Study Sites. J Addiction Prevention, 1(3), 8

- Socialdepartementet (2010). Alkohollagen (2010:1622). Regeringskansliet. [Ministry of Social affairs, Government offices. The Alcohol Act, 2010:1622].

- Sterk, C. E., Klein, H., & Elifson, K. W. (2008). Young Adult Ecstasy Users and Multiple Sexual Partners: Understanding the Factors Underlying this HIV Risk Practice. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 40(3), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2008.10400638

- Sundin, E., Landberg, J., & Ramstedt, M. (2017). Negativa konsekvenser av alkohol, narkotika och tobak – en studie med fokus på beroende och problem från andras konsumtion i Sverige 2017. [Negative consequences of alcohol, drugs and tobacco - a study focusing on addiction and problems from other people's consumption in Sweden 2017][In Swedish]. Centralförbundet för alkohol- och narkotikaupplysning, CAN. Rapport 174. [The Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs]

- SVT Sveriges Television (2018). [SVT, Swedish Public Service Television]. Polisens oroväckande statistik: Allt fler har lämnat för andra jobb [Worrying statistics from the Police: More staff have left for other jobs] [in Swedish] https://www.svt.se/nyheter/inrikes/polisens-orovackande-statistik-allt-fler-har-lamnat-for-andra-jobb: SVT.

- Van Buskirk, J., Griffiths, P., Farrell, M., & Degenhardt, L. (2017). Trends in new psychoactive substances from surface and “dark” net monitoring. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(1), 16–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30405-9

- Vasica, G., & Tennant, C. C. (2002). Cocaine use and cardiovascular complications. The Medical Journal of Australia, 177(5), 260–262. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04761.x

- Wallin, E., Gripenberg, J., & Andreasson, S. (2005). Overserving at licensed premises in Stockholm: Effects of a community action program. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 66(6), 806–814. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2005.66.806

- Wallin, E., Norstrom, T., & Andreasson, S. (2003). Alcohol prevention targeting licensed premises: A study of effects on violence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64(2), 270–277. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2003.64.270

- Weir, E. (2000). Raves: A review of the culture, the drugs and the prevention of harm. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de L'Association Medicale Canadienne, 162(13), 1843–1848.

- White, H. R., Jiao, Y., Ray, A. E., Huh, D., Atkins, D. C., Larimer, M. E., Fromme, K., Corbin, W. R., Baer, J. S., LaBrie, J. W., & Mun, E.-Y. (2015). Are There Secondary Effects on Marijuana Use From Brief Alcohol Interventions for College Students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 76(3), 367–377. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2015.76.367

- Whittingham, J. R. D., Ruiter, R. A. C., Bolier, L., Lemmers, L., Van Hasselt, N., & Kok, G. (2009). Avoiding Counterproductive Results: An Experimental Pretest of a Harm Reduction Intervention on Attitude Toward Party Drugs Among Users and Nonusers. Substance Use & Misuse, 44(4), 532–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080802347685

Appendix

A few questions about illicit drugs

STockholm prevents Alcohol and Drug problems (STAD), an educational resource and research center for prevention of alcohol and drug problems, are conducting a survey to gain more knowledge about the occurrence and use of illicit drugs at licensed premises in Stockholm, for example, how common it is that patrons are intoxicated by illicit drugs. Who would be better suited to answer such questions than people who work at the licensed premises? That is why we are directing this study to you who is attending the training in STADs Responsible Beverage Serving program.

Your participation is of course voluntary and you answer the questions anonymously.

After completing the questionnaire, you can put it in the envelope and seal.

1) Are you a man or a woman?

□ Man

□ Woman

2) How old are you? ______ years.

3) For how long have you been working in the hospitality industry? __________years___________months.

4) Which is your main role at work? You can mark several alternatives.

□ Bartender

□ Head waiter

□ Waiting staff

□ Owners

□ Restaurant manager

□ Operation manager

□ Security guard

□ Door staff

□ Something else, such as ________________________

5) Do you ever see patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs at licensed premises in Stockholm?

□ Yes, almost every night

□ Yes, every week

□ Yes, every month

□ Yes, every six months

□ No

□ Don’t know

Comment:_________________________________________________

6) How easy do you think it is to see if a patron is intoxicated by illicit drugs?

□ Very easy

□ Easy

□ Neither easy nor difficult

□ Difficult

□ Very difficult

□ Don’t know

Comment:_________________________________________________

7) Have you seen anyone being offered illicit drugs at licensed premises in Stockholm?

□ Yes, almost every night

□ Yes, during the last week

□ Yes, during the last month

□ Yes, during the last six months

□ Yes, during the last year

□ No

□ Don’t know

Comment:__________________________________________________

8) Have you seen anyone taking illicit drugs at licensed premises in Stockholm?

□ Yes, almost every night

□ Yes, during the last week

□ Yes, during the last month

□ Yes, during the last six months

□ Yes, during the last year

□ No

□ Don’t know

Comment:__________________________________________________

9) Compared to 5 years ago, would you say there are currently more or less illicit drugs at licensed premises in Stockholm?

□ There are currently more illicit drugs

□ No difference

□ There are currently less illicit drugs

□ Don’t know

Comment:_________________________________________________

10) Have you ever asked a patron intoxicated by illicit drugs to leave the licensed premise where you work?

□ Yes, once

□ Yes, several times

□ No

Comment:_________________________________________________

11) Do you think patrons intoxicated by illicit drugs should be asked to leave licensed premises?

□ Yes, always

□ Yes, but only if they misbehave

□ No

□ Don’t know

Comment:_________________________________________________

12) Do you think it should be illegal to be intoxicated by illicit drugs?

□ Yes

□ No

□ Don’t know

Comment:_________________________________________________

13) Do you think illicit drugs should be legal in the same way as tobacco and alcohol are?

□ Yes

□ No

□ Don’t know

Comment:_________________________________________________

14) If you would see someone take illicit drugs at your licensed premise, what would you do? You can mark several alternatives.

□ Contact a manager or other colleague

□ Contact door staff

□ Call the police

□ Don’t know

□ Nothing

Comment:_________________________________________________

15) Have you ever been offered any of the following illicit drugs? Answer by ticking a box at each row.

…namely _________________________________________________

If you have never been offered illicit drugs, go to question 18.

16) Where were you offered to try illicit drugs? Answer by ticking a box at each row

…namely_________________________________________________

17) Have you been offered illicit drugs at a licensed premise in Stockholm?

□ Yes, in the last week

□ Yes, in the last month

□ Yes, in the last six months

□ Yes, in the last year

□ Yes, but several years ago

□ No, that has never happened

Comment:__________________________________________________

18) Have you used any of the following illicit drugs? Answer by ticking a box at each row.

…namely____________________________________________________

If you have never used illicit drugs, go to question 23.

19) When did you last use illicit drugs?

□ Last week

□ Last month

□ Last six months

□ Last year

□ Several years ago

□ Have never used illicit drugs

Comment:_______________________________________________

20) Where have you used illicit drugs? Answer by ticking a box at each row.

…namely________________________________________

21) Have you used illicit drugs at a licensed premise in Stockholm?

□ Yes, once

□ Yes, several times

□ No

Comment:__________________________________________________

22) When did you last use illicit drugs at a licensed premise in Stockholm?

□ Last week

□ Last month

□ Last six months

□ Last year

□ Several years ago

□ Have never used illicit drugs

Comment:__________________________________________________

23) Have you ever used anabolic androgenic steroids (AAS) or other doping without a medical prescription?

□ Yes, in the last week

□ Yes, in the last month

□ Yes, in the last six months

□ Yes, in the last year

□ Yes, but several years ago

□ No, have never used doping

Comment:__________________________________________________

24) What type of licensed premise are you working at?

□ Bar/pub

□ Restaurant

□ Nightclub

□ Hotel

□ Student pub

□ Other type of premise, namely _____________________________

Comment:_________________________________________________

25) What do you think the licensed premise can do to reduce drug use/abuse among patrons and employees?

Thank you for your suggestions! We are very interested in what you, who is working at a licensed premise, think about this.

26) What do you think the police and other authorities can do to reduce drug use/abuse among patrons and employees?

Thank you for your suggestions! We are very interested in what you, who is working at a licensed premise, think about this.

27) What do you think of the questions you have answered? You can mark several alternatives.

□ Very good

□ Good

□ Neither good nor bad

□ Bad

□ Very bad

□ Interesting

□ Too personal

□ Difficult to understand

Comment:__________________________________________________

Thank you for your participation!