ABSTRACT

Background

People should be able to quit or moderate their drinking without negative social consequences, but studies have shown how nondrinkers often face pressure and negative reactions. As previous research has mostly focused on youth, we conducted a population-level study of the ways adult nondrinkers encounter their drinking companions on drinking occasions and what kinds of reactions they perceive from their social environments.

Method

The data were based on the Finnish Drinking Habits Survey (FDHS), a general population survey of Finns aged 15–79 collected in 2016 (N = 2,285; 330 nondrinkers; response rate 60%). Characteristics of drinking occasions where nondrinkers participate (“non-drinking occasions”) were measured through self-reports of frequency, time, purpose, and social companion on those occasions. Nondrinkers’ experiences of non-drinking occasions and reactions from the social environment were measured by question batteries on social consequences.

Results

Compared with drinking occasions, non-drinking occasions occurred more often at family events at home than on late-night drinking occasions. Accordingly, nondrinkers reported relatively low levels of negative consequences, and the reported consequences were least frequent in the oldest age group. Nondrinkers reported mostly positive feedback from people around them, more often from family members than from peers. However, negative consequences were reported in all studied groups, most commonly among youth and former drinkers.

Conclusions

The study indicates that nondrinkers’ social environments may be more supportive than what has been suggested previously, yet coping mechanisms are required especially from youth and former drinkers. The positive social experiences of being a nondrinker should guide the promotion of moderate and non-drinking.

Introduction

Over the past 10 to 15 years, per capita alcohol consumption has declined in several high-income countries (Chang et al., Citation2016; Holmes et al., Citation2019; WHO, Citation2018). This trend seems to be particularly strong among younger cohorts, among whom alcohol abstinence has become more common, and the amount of alcohol consumed among drinkers has declined (Livingston et al., Citation2016: Kraus et al., Citation2015; Meng et al., Citation2014; Vashishtha et al., Citation2021). The body of literature on this declining trend in youth drinking has been growing, yet alcohol abstinence in the adult population has received less attention. This is despite the fact that the prevalence of nondrinkers has increased in the adult population in many countries, e.g. Finland, Sweden, Australia, and the UK (Mäkelä, Citation2018; Chang et al., Citation2016; Kraus et al., Citation2015; Meng et al., Citation2014). Between 2000 and 2016 in the Finnish population aged 15–69, the proportion of nondrinkers has risen from 8% to 12% among men and from 9% to 15% among women (Mäkelä, Citation2018).

Nondrinkers, their motivations, and how they are perceived by drinkers have received more attention in research, especially with regard to new meanings of drinking among young adults (Banister et al., Citation2019; Calluzzi & Pennay, 2019; Jacobs et al., Citation2018). According to previous studies of nondrinkers’ motives, nondrinkers report a variety of reasons why they choose to abstain. For example, they may dislike alcohol’s taste and effects, they may have experienced adverse consequences from others’ drinking, or their abstinence may relate to lifestyle preferences, health status, religion, or a desire for authenticity and personal agency (Conroy & De Visser, Citation2015; Graber et al., Citation2016; Huang et al., Citation2011; Rinker & Neighbors, Citation2013; Katainen & Härkönen, Citation2018; Piacentini & Banister, Citation2009). A recent study also highlights pleasurable aspects of non-drinking by demonstrating how it can be experienced as an alternative way of seeking enjoyment and a sense of belonging with others (Caluzzi et al., 2020).

Alcohol abstinence, however, can lead to negative social consequences and can be viewed as deviant and unusual behavior, especially at social occasions during which people typically drink (Bartram et al., Citation2017; Herman-Kinney & Kinney, Citation2013; Romo et al., Citation2015). In cultures where drinking is a cultural norm, abstinence can be seen as stigmatized, relating to both felt and enacted consequences. Enacted stigma refers to episodes of discrimination based on the unacceptability of abstinence, whereas felt stigma refers either to shame of being associated with the negative characteristics of a nondrinker or to fear of encountering negative consequences (e.g. Scambler, Citation2004). According to the study by Cheers et al. (Citation2021), drinkers may perceive nondrinkers as judgmental in drinking situations and therefore posing a threat to the group’s aim to have fun and connect with each other. Also, nondrinkers may be viewed as unsociable compared with drinkers (Regan & Morrison, Citation2013), and male nondrinkers may be viewed as less masculine (Conroy & De Visser, Citation2013). Nondrinkers’ encounters with enacted stigma vary. They may experience bullying, expressions of nonacceptance (such as negative comments), and sometimes even physical confrontations (Paton-Simpson, Citation2001).

Previous studies have examined how young nondrinkers cope with and manage the enacted stigma in situations in which other people drink. These studies have pointed out how nondrinkers are often required to justify their behavior on drinking occasions (Romo et al., Citation2015). Studies have highlighted how nondrinkers are compelled to legitimize abstinence, citing reasons that are viewed as “valid,” such as religion, health issues, or an athletic lifestyle (Advocat & Lindsay, Citation2015; Conroy & De Visser, Citation2014; Nairn et al., Citation2006). As for the felt stigma, nondrinkers may be required to adopt strategies to hide the fact that they are not drinking in order to pass as drinkers (Herman-Kinney & Kinney, Citation2013), or they may withdraw from drinking situations or avoid them completely to lessen social risks (Bartram et al., Citation2017; Herman-Kinney & Kinney, Citation2013). Findings from previous studies have also illustrated how nondrinkers are compelled to construct positive counter-identities to challenge the stigma of abstinence (Conroy & De Visser, Citation2014; Supski & Lindsay, 2017). However, recent research has pointed out how nondrinkers also resist cultural expectations that abstinence should be central to their social identities (Banister et al., Citation2019).

Drinking and abstinence are learned social behaviors that are affected by indirect influences, such as perceived drinking-related norms, and direct influences, such as drinking habits prevalent in social environments and pressures and cues concurrent with drinking situations (Borsari & Carey, Citation2001). For example, drinking tends to be heavier in mixed-gender groups (Thrul et al., Citation2017), and friends are likely to share similar habits regarding drinking (Burk et al., Citation2012). According to a study by Mäkelä & Maunu (Citation2016), almost half of the Finnish population and Finnish nondrinkers reported that they had experienced direct pressure to drink during the previous 12 months. Previous studies also suggest that reactions to abstinence vary, e.g. friends, family members, and coworkers are likely to react differently to abstinence. Friends are more likely to pressure peers to drink more (Kuntsche et al., Citation2004), whereas family members typically encourage abstinence (Holmila et al., Citation2009). However, previous research on social influences and pressures to drink almost exclusively has focused on adolescents and young adults in college environments (Monk & Heim, Citation2014). The reasons for this may be that the young are more likely to engage in heavy drinking activities and be more susceptible to peer pressure and drinking-related cues than adults (Kuntsche et al., Citation2004; Nash et al., Citation2005) and also because the young often seem to be easier objects of study and concern. Still, adults are not immune to these influences, but very little is known about negative social consequences and reactions to abstinence experienced by adults.

In this study, we wish to shed more light on the question of how adult nondrinkers are encountered in a society geared toward the norm of drinking and how nondrinkers experience these encounters. We studied these encounters first by analyzing in what types of social situations nondrinkers (including both lifetime abstainers and former drinkers) are typically exposed to other people’s drinking. We looked at these occasions from the point of view of the nondrinker; we call these “non-drinking occasions.” The pressures to drink are likely to be strongest in these situations. We also compared the characteristics of these situations to the characteristics reported by drinkers of their drinking occasions to see what is specific to the non-drinking occasions. The differences are indicative of the types of drinking occasions that nondrinkers consider best to avoid.

Second, we studied the social consequences that adult nondrinkers experience on non-drinking occasions. We measured these social consequences by analyzing nondrinkers’ self-reports of how often they have experienced social pressure and negative reactions, what kinds of attitudes toward abstinence nondrinkers experience from family, friends, and/or colleagues, and how the experienced consequences depend on the respondent’s gender, age, and abstinence status. As previous studies of abstinence and its social consequences have mostly focused on youth and based on qualitative data, there is very little knowledge of the extent to which the adult nondrinkers are susceptible to negative reactions and pressure. Finland makes an interesting case for such a study, as drinking (and often excessive drinking) is a predominant cultural norm. To our knowledge, this is the first study anywhere to explore the social consequences of abstinence at the population level.

Methods

Data

The data were based on the Finnish Drinking Habits Survey (FDHS), a general population survey of Finnish drinking carried out in 2016. The survey covered Finns aged 15–79, with 2,285 respondents and a response rate of 60%. This was a simple random sample from the national Population Information System, excluding the Åland Islands (0.5% of the population), the homeless, and the institutionalized (1.5%). Young adults ages 18–25 were given a two-fold selection probability in the random sampling compared with other age groups, which is taken into account in analyses through weighting (see below). The survey was carried out in the autumn through face-to-face interviews conducted by Statistics Finland. In the pre-notification letter, it was explained that responses were important regardless of their drinking status. Furthermore, interviewers were instructed to motivate nondrinkers and drinkers to participate in equal measure. FDHS was evaluated and approved for ethical practices by ethical committees from the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare THL and Statistics Finland.

Measurements

Early on in the interviews, the respondents were identified as either drinkers or nondrinkers. The criterion for a nondrinker was not having consumed any alcohol in the previous 12 months, not even small amounts. If nondrinkers had drunk alcohol prior to the most recent 12-month period, they were categorized as former drinkers—and if not, as lifetime abstainers. Most of the questions for nondrinkers were closed-ended, with a limited set of response options.

At the individual level, the social consequences of abstinence were measured by a nine-item battery, with the following introduction: “When you think about the past 12 months, how often has the following occurred…?” The nine items included questions about experiences of both felt and enacted stigma (such as being pressured to drink), proper nonalcoholic alternatives to alcoholic drinks, coping, and social rejection. The response alternatives were Often, Occasionally, Seldom, and Never (see Appendix 1). Attitudes toward abstinence in three different social environments were asked: “What are your family members’ attitudes towards you not drinking alcohol?” The same question was repeated for “friends” and for “co-workers or schoolmates.” The response alternatives were “Only positive,” “Mostly positive,” “Not positive or negative,” “Mostly negative,” and “Only negative.”

Unique to the current data was a set of questions specific to (non-)drinking occasions. For drinkers, these concerned occasions when respondents themselves drank. For nondrinkers, the questions were about occasions when somebody else in their presence drank. First, a question about the overall frequency of such occasions was posed. The length of the period to be covered, i.e. the “survey period,” depended on this frequency. This was seven days for respondents experiencing such occasions most frequently and an entire year for respondents experiencing such occasions least frequently, with five frequency–period options in between. Characteristics of all the (non-)drinking occasions during this survey period were asked about. Their expected number for all was four by design, and in practice, 0–16 for drinkers and 0–10 for nondrinkers. In total, 6,730 drinking occasions were reported by 1,891 drinkers (97 percent of all 1,955 drinkers), and 590 non-drinking occasions were reported by 218 nondrinkers (65 percent of all 330 nondrinkers). There were 64 drinkers and 112 nondrinkers who had no drinking/non-drinking occasions during the survey period.

The questions posed about each occasion were the same for drinkers and nondrinkers (except those concerning the amounts drunk by the respondent). In the current analysis, we use the date, start and end times, location, social context, and those present during the occasion. The location of drinking (the main location if several were reported) comprised: (1) home surroundings (their own or others’ home or summer house), (2) licensed premises, and (3) other locations (e.g. outdoors).

The day of the week was categorized as Monday–Thursday, Friday–Saturday, and Sunday when presenting results in a table format, as this divides the days into homogeneous categories with respect to drinking in Finland (Mäkelä & Warpenius, Citation2020). After midnight, the next day was used for the categorization. Timing within the day was characterized by the time when the drinking occasion ended. In a graph of the proportion of the respondents being in a (non-) drinking occasion during any given hour of the week, a drinking occasion lasting from 6:00–9.30 p.m. (for example) was included in all one-hour slots beginning with the 6–7 p.m. slot and ending in the 9–10 p.m. slot.

Each respondent was asked to choose what type of occasion was in question from a list of nine options: “What type of situation was it? You can choose several: Paying visits, Entertainment, Game or hobby, Meeting friends, Celebration (e.g. birthday, wedding, a public holiday), Party or night out, Meal, Work occasion (e.g. work lunch), Sauna bathing, and No special occasion—originally based on Simpura (Citation1983) but developed thereafter. Finally, respondents reported whether a partner, any children under 16, family members or relatives, friends, fellow employees, or anyone of the opposite sex had been present, and how many people over age 15 were present.

Analysis

The statistical analysis of the data comprised primarily simple tabulations. At the individual level, the differences between groups of respondents in reporting consequences or experiences were tested using logistic regression. Analysis weights were derived using post-stratification for gender, age, and region, and they were used in all analyses to restore the population representation and correct the deviation caused by the oversampling of young adults. Hence, the results presented here can be considered to represent the general population of Finland aged 15–79.

We tested whether the type of occasion (non-drinking occasion vs. drinking occasion) explained the differences in the characteristics of the occasions. Before combining occasion-level data across individuals, it was important to account for the fact that some people responded for one week only, some for a whole year, and others for some duration in between. To make the responses representative of all Finnish drinking/non-drinking occasions, all occasions were scaled so that they represented occasions for a whole year before calculating the proportions. The number of occasions in a 7-day survey period was multiplied by 52, occasions in a 2-week period by 26, occasions in a 52-week period by 1, etc. Differences in the characteristics of drinking occasions and non-drinking occasions were tested using logistic regression models with the characteristics—one at a time—as dependent variables (e.g. was the company a “partner only,” were children present, etc.). And the independent variable was whether the occasion was a non-drinking occasion or a drinking occasion. The clustering of the occasions within respondents was taken into account using generalized estimating equations (using the GENMOD procedure in the SAS statistical package). When scaling the observations to a year, it was ensured by calibration that this did not lead to a spuriously large number of observations in the tests—the weighted total number of occasions matched the observed one.

Results

In the whole data describing the Finnish population aged 15–79, 14.6% were nondrinkers (weighted proportion; 330 respondents). Of the nondrinkers, 57% were female, 39% were aged 60 and up, and 57% were former drinkers (). The former drinkers’ drinking frequency before abstinence was somewhat lower on average than that of current drinkers in 2016. But among them, the proportion of very frequent drinkers (4–5 times per week or more) had been about one-fourth higher than among current drinkers (6.9% vs. 5.5%). A note needs to be made here about the interpretation of the number of observed (non-)drinking occasions, which is complicated by the structure of the data. For example, men and women in the sample reported almost as many non-drinking occasions (294 and 296), but when these were scaled to a year, a much higher proportion of such occasions occurred among women than among men (63% vs. 37%). The latter is the correct depiction of the distribution in the population. The n’s in the sample are similar because women were assigned shorter survey periods (because they reported having such non-drinking occasions more frequently). Compared to the distribution of nondrinkers (i.e. people), the non-drinking occasions were more common not only among women but also among middle-aged respondents and former drinkers. This also means that both older and younger respondents reported fewer non-drinking occasions than could be expected based on their share of the population.

Table 1. Number of nondrinkers, “non-drinking occasions,” drinkers and drinking occasions, and their distribution (%) by sex, age, and abstinence status1.

Often, the non-drinking as drinking occasions were similar social situations. Both took place most frequently on weekend evenings at home so that only the partner and possibly children were present (). The most common characterization of the type of non-drinking occasions was “no special occasion.”

Table 2. Characteristics of (non-)drinking occasions (%) by type of respondent (nondrinkers and drinkers), and the odds ratios from models (for each row separately) comparing the odds of the given characteristic in the occasions of nondrinkers compared to drinkers.

A more careful comparison of non-drinking and drinking occasions allowed the examination of the characteristics that were more common in either the drinking or the non-drinking occasions (). The greatest differences were found in the ending time and the social context. Compared to those of drinkers, nondrinkers’ occasions clearly ended earlier, and the social context was much more often “no special occasion” and much less often “going to sauna” or “entertainment game or hobby.” Correspondingly, among nondrinkers, it was more often the case that children and other family members and friends were present, and the occasion took place during the week, and the location was “other location” (home surroundings less often). These may be weddings or other such get-togethers that often take place in “other locations.”

Some of the prominent differences in the sample were not statistically significant (paying visits, meals), indicating that these may more likely be accounted for by random variation. In some of these cases, clustering within individuals may have been particularly high, and taking that into account in the tests reduced the statistical significance.

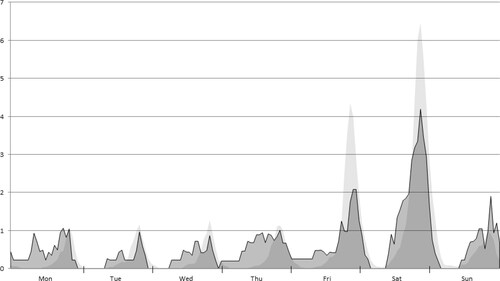

In , we took a closer look at how the timing of non-drinking occasions differed from those of drinking occasions during the week. The figure confirms the main pattern (also seen in ) of peaks occurring in the evenings, especially on Fridays and Saturdays, and non-drinking occasions occurring earlier and spread more evenly across daily hours. Also, the peaks on Friday and Saturday evenings were not as pronounced for non-drinking occasions as for drinking occasions.

Figure 1. Distribution of non-drinking (medium gray with black borders)ǂ and drinking (light gray)ǂ occasions across hours of the week (% of the whole week’s (non-)drinking occasions)*.

ǂAreas with dark gray are areas where non-drinking and drinking occasion proportions overlap each other.

*The weekday label is centered at 12 o’clock noon, vertical cross bars on x-axis denote midnight.

Next, we turn to the matter of the kinds of social consequences nondrinkers experience when encountering drinkers. The most commonly reported social consequence from abstinence was that the respondent was prompted to explain or justify why they chose not to drink (). Of the non-drinking respondents, 24% reported that this happened often or occasionally during the previous 12 months. Experiences of feeling like an outsider due to abstinence were almost as common (21%), with 17% having been pressured to drink. The most rarely reported consequences were getting into arguments (2%) and a need to conceal abstinence (4%). Experienced negative consequences were significantly more prevalent among those under age 60 and among former drinkers. Pressure to drink was reported more often in the 15–29 and 30–59 age groups than among older respondents, and more often among former drinkers than among lifetime abstainers. Social rejection was reported the most among 30- to 59-year-olds and among former drinkers more than among lifetime abstainers. No statistically significant differences existed between men and women in reported consequences.

Table 3. Social consequences of abstinence: proportion of nondrinkers responding “often” or “occasionally,” %.

Most nondrinkers had experienced only positive attitudes toward their abstinence from family members, and family members’ attitudes were reported to be more positive than those of friends, coworkers, or schoolmates (). These results did not differ between genders or age groups, but lifetime abstainers reported that their family members and friends have more positive attitudes toward their abstinence than former drinkers.

Table 4. Attitudes in the social environment toward abstinence: proportion of respondents reporting only positive reactions from others (%).

Discussion

Previous studies of abstinence have emphasized the negative social consequences that nondrinkers may face and that coping strategies are required from nondrinkers as well as drinkers who aim to drink less (Cherrier & Gurrieri, Citation2013; Nairn et al., Citation2006; Paton-Simpson, Citation2001). The vast majority of studies of these experiences have been qualitative and focused on youths, and very little is known about the prevalence of negative social consequences from abstinence in a general adult population. Finland is an example of a country where drinking, sometimes heavy drinking, is expected at many occasions, and this particularly has been the case among young people (Maunu, Citation2014). In this study, we were able to analyze the characteristics of occasions where nondrinkers most likely confront pressure and other negative consequences, as well as self-reports of coping mechanisms (felt stigma) and the reaction they have faced (enacted stigma) due to their abstinence. We did not concentrate only on youths. Rather, the data enabled comparisons between age groups and between former drinkers and lifetime abstainers.

Non-drinking occasions were most common among women, middle-aged respondents, and former drinkers. Our results showed that non-drinking occasions shared many characteristics with drinking occasions. Both often took place on weekend evenings at home with one’s partner. However, the non-drinking occasions more often took place earlier in the day and on weekdays compared to drinking occasions, which accumulated during later weekend hours. It seems that the most typical non-drinking occasions were when a partner is having a drink at home or related to family events, as family members and children were reported to be present more often during nondrinkers’ than drinkers’ occasions.

Our results also showed that family members were reported to be far more positive toward alcohol abstinence than were friends and colleagues, coinciding with the previous research finding of family members being more supportive as “beneficiaries” of abstinence, especially in the case of former drinkers with problematic drinking behavior in the past (Holmila et al., Citation2009; Raitasalo & Holmila, Citation2005). Given that the most common non-drinking occasions were with family members, it is not surprising that non-drinking FDHS respondents reported relatively low levels of negative social consequences. This indicates that nondrinkers often experience their encounters with drinkers as non-problematic. The most severe consequences of enacted stigma, such as getting into arguments, were rarely reported.

On the other hand, it is equally important to note that people in all age groups in this study (not just young people) reported negative social consequences, and those negative consequences reflected both felt and enacted stigma. Compared to lifetime abstainers, middle-aged former drinkers reported more non-drinking occasions, more pressure and rejection, and more negative reactions, especially from their friends and coworkers. This describes the social challenges that people may face if they wish to reduce or quit drinking and yet maintain their social relations, which has also been documented by Bartram et al. (Citation2017) among Australian adults who had stopped or considerably reduced their alcohol use.

By and large, men and women reported consequences equally. Findings from previous research on social pressure to drink suggest that men experience more pressure than women (e.g. Astudillo et al., Citation2013) and that it is easier for women to deal with the enacted stigma by finding acceptable reasons to drink less or not at all (Emslie et al., Citation2012). According to our results, it seems that Finnish nondrinkers, both men and women, experienced the felt and enacted stigma of abstinence in a relatively similar manner.

Not surprisingly, older people reported negative social consequences to a lesser extent than younger groups. Traditionally, abstinence has been common in older age groups in the Nordic countries, and abstinence is still more common among older people than in the adult population, especially among women (Tigerstedt et al., Citation2020). Older people may also suffer from health conditions and issues that require moderation or abstinence. Therefore, their abstinence is well understood by others. Our results on non-drinking occasions showed that older people had fewer non-drinking occasions in their lives, suggesting that they are also less frequently exposed to social situations where other people drink, which contributes to fewer negative consequences.

Young nondrinkers, by contrast, seemed to have the most experiences of felt and enacted stigma. They reported that they had been prompted to explain or justify abstinence. In particular, young respondents reported that they avoided situations in which other people drink. Young people’s drinking occasions are more concentrated in the late hours of the night than are older people’s (Mäkelä & Warpenius, Citation2020). The finding that young nondrinkers avoided such occasions could also be seen in our results on non-drinking occasions, which were clearly less common in the late hours of the night than were drinking occasions. Previous studies have shown that friends are the most likely source of social pressure to drink (Kuntsche et al., Citation2004). Drinking occasions with friends may involve more pressure because at many social occasions with them (such as nighttime partying), drinking can be expected as a form of social ritual (Cheers et al., Citation2021; Maunu, Citation2014; Katainen & Rolando, Citation2015). Skipping drinking occasions may be a rational escape route from this pressure, which likely shields a nondrinker from experiencing negative consequences. On the other hand, a study by Conroy and De Visser (2018) demonstrated that young nondrinkers identify many benefits from social non-drinking, such as a higher quality of social life. According to Graber et al. (Citation2016), nondrinkers and moderate drinkers aim at “the sweet spot” of a desired physical and psychological state in a drinking situation by balancing subjective well-being and challenging aspects of situations where others drink. Our results on the timing of non-drinking occasions suggest that this sweet spot could be found temporally during weekend evenings, avoiding the late nights when blood alcohol concentrations rise (Mäkelä & Warpenius, Citation2020).

The study’s limitations include the small number of non-drinking respondents, as it is based on a general survey of drinking habits rather than a survey specifically on non-drinking. The proportion of nondrinkers (14.6%) was similar to that found in population-based general health studies (FinHealth 2017: 16% in the 30–64 age group (Koponen et al., Citation2018); ATH Study 2016: 14% in the 20–64 age group (Yearbook…, 2021)), so there is no reason to assume that nondrinkers would have dropped out from the “Drinking Habits Survey” to a greater extent. Moreover, having been able to examine the prevalence of perceived negative outcomes in a general population is also a strength of the study. Other limitations include difficulty in considering how respondents interpreted the survey questions. Some pilot testing was done before the survey, but it was not sufficient to reliably evaluate questions to minority respondents such as nondrinkers, and it was not nearly as ideal as could be achieved by a proper qualitative approach to this matter. Similarly, a qualitative study could have dug deeper into the respondents’ motivations and varying life histories. It is also difficult to assess whether systematic differences exist in how people respond and how willing they are to report negative reactions. Additionally, in an ideal situation, drinkers would also have been asked about non-drinking occasions and about consequences of their more occasional non-drinking because it is important to understand how people respond to nondrinkers (people) as well as non-drinking (behavior) in whomever the latter occurs. As in all surveys, the drinkers and nondrinkers who responded to the survey are not necessarily similar in all respects to the drinkers and nondrinkers who decided not to respond. The analysis of non-drinking situations can provide only rough estimates of the situational variance between drinkers and nondrinkers, but to our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze these differences.

Conclusions

Nondrinkers are a minority in high-income countries, but their proportion seems to be growing. As previous studies have typically focused on adolescents and young adults, the present study provides insights into how sanctioned abstinence is when the adult population is considered, how nondrinkers encounter drinkers on drinking occasions, and how they experience these encounters. The study shows that negative social consequences from abstinence are reported in all age groups, but that they are the least frequent in older age groups. In addition, the results indicate that abstinence may not be as socially sanctioned even among youths, as has been emphasized in previous studies of how young people manage the pressures to drink in the “culture of intoxication” (e.g. Herman-Kinney & Kinney, Citation2013; Advocat & Lindsay, Citation2015). Instead, nondrinkers in all age groups reported mostly supportive social environments and social spaces in which coping strategies are not required constantly. Nondrinkers who confront little pressure and negative consequences have successfully managed to integrate their lifestyle into their everyday life in a culture that promotes drinking. However, regarding preventive efforts that aim to promote the adoption of less harmful drinking habits and reduce drinking-related harm, such efforts would be even more feasible if those who wish to cut down on their drinking or abstain could avoid negative feedback altogether. Resilience is especially required from former drinkers, indicating that drinking cultures need to be challenged to better facilitate abstinence and moderation of drinking.

Health promotion efforts should especially focus on alleviating the strong distinction between types of drinkers and nondrinkers, as Banister et al. (Citation2019) have suggested, to create a more tolerant culture toward abstinence and light drinking, and to normalize non-drinking (also see Graber et al., Citation2016). Future research may also play a part by emphasizing the heterogeneity of motivations and experiences of nondrinkers as well as by studying concrete methods by which cultures could be changed to be more tolerant toward non-drinking. Further research is especially needed on the types of light and nondrinkers and their motives in the adult population. Moreover, suitable datasets are required to examine in which population groups non-drinking as well as light drinking are gaining ground. Such studies should not involve just young people because social pressure to drink and drinking-related norms concern all age groups.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest, but they would like to disclose that the survey data collection was partially funded by the Finnish state-owned alcohol retail monopoly, Alko Ltd. Alko had no role in the content of research reports or any capability to affect publication decisions. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Advocat, J., & Lindsay, J. (2015). To drink or not to drink? Young Australians negotiating the social imperative to drink to intoxication. Journal of Sociology, 51(2), 139–153. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783313482367

- Astudillo, M., Connor, J., Roiblatt, R. E., Ibanga, A. K. J., & Gmel, G. (2013). Influence from friends to drink more or drink less: A cross-national comparison. Addictive Behaviors, 38(11), 2675–2682. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.06.005

- Banister, E., Conroy, D., & Piacentini, M. (2019). Non-drinkers and non-drinking: A review, a critique and pathways to policy. In D. Conroy & F. Measham (Eds.), Young adult drinking styles. Current perspectives on research, policy and practice (pp. 213–232). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Banister, E., Piacentini, M., & Grimes, A. (2019). Identity refusal: Distancing from non-drinking in a drinking culture. Sociology, 53(4), 744–761. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038518818761

- Bartram, A., Eliott, J., & Crabb, S. (2017). ‘Why can’t I just not drink?’ A qualitative study of adults’ social experiences of stopping or reducing alcohol consumption . Drug and Alcohol Review, 36(4), 449–455. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12461

- Borsari, B., & Carey, K. B. (2001). Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse, 13(4), 391–424. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-3289(01)00098-0

- Burk, W. J., van der Vorst, H., Kerr, M., & Stattin, H. (2012). Alcohol use and friendship dynamics: Selection and Socialization in early middle- and late-adolescence peer networks. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 73(1), 89–98.

- Caluzzi, G., MacLean, S., & Pennay, A. (2020). Re-configured pleasures: How young people feel good through abstaining or moderating their drinking. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 77, 102709. Volume https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102709

- Caluzzi, G., & Pennay, A. (2019). Alcohol, young adults and the new millennium: Changing meanings in a changing social climate. In D. Conroy & F. Measham (Eds.), Young adult drinking styles. Current perspectives on research, policy and practice (pp. 47–65). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chang, G., Leung, K., Quinn, C., Connor, J., Hides, L., Gullo, M., Alati, R., Weier, M., Kelly, A., & Hall, W. (2016). Trend in alcohol use in Australia over 13 years: Has there been a trend reversal? BMC Public Health, 16, 1070.

- Cheers, C., Callinan, S., & Pennay, A. (2021). The ‘sober eye’: Examining attitudes towards non-drinkers in Australia. Psychology & Health, 36(4), 385–404.

- Cherrier H., & Gurrieri L. (2013). Anti-consumption Choices Performed in a Drinking Culture: Normative Struggles and Repairs. Journal of Macromarketing, 33(3), 232–244. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146712467805

- Conroy, D., & De Visser, R. (2013). ‘Man up!’ Discursive constructions of non-drinkers among UK undergraduates . Journal of Health Psychology, 18(11), 1432–1444. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105312463586

- Conroy, D., & De Visser, R. (2014). Being a non-drinking student: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Psychology & Health, 29(5), 536–551. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2013.866673

- Conroy, D., & De Visser, R. (2015). The importance of authenticity for student non-drinkers: An interpretive phenomenological analysis. Journal of Health Psychology, 20(11), 1483–1493. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105313514285

- Conroy, D., & De Visser, R. (2018). Benefits and drawbacks of social non-drinking identified by British university students. Drug and Alcohol Review, 37(s1), S89–S97. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12610

- Emslie, C., Hunt, K., & Lyons, A. (2012), Older and wiser? Men’s and women’s accounts of drinking in early mid-life. Sociology of Health & Illness, 34: 481–496. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01424.x

- Graber, R., de Visser, R., Abraham, C., Memon, A., Hart, A., & Hunt, K. (2016). Staying in the ‘sweet spot’: A resilience-based analysis of the lived experience of low-risk drinking and abstention among British youth . Psychology & Health, 31(1), 79–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2015.1070852

- Herman-Kinney, N. J., & Kinney, D. A. (2013). Sober as deviant: The stigma of sobriety and how some college students ‘stay dry’ on a ‘wet’ campus. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 42(1), 64–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241612458954

- Holmes, J., Ally, A. K., Meier, P. S., & Pryce, R. (2019). The collectivity of British alcohol consumption trends across different temporal processes: a quantile age–period–cohort analysis. Addiction, 114: 1970–1980. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14754

- Holmila, M., Raitasalo, K., Knibbe, R., & Selin, K. (2009). Country variations in family members’ informal pressure to drink less. Contemporary Drug Problems, 36(1–2), 13–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/009145090903600103

- Huang, J. H., DeJong, W., Schneider, S. K., & Towvim, L. G. (2011). Endorsed reasons for not drinking alcohol: A comparison of college student drinkers and abstainers. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 34(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-010-9272-x

- Jacobs, L., Conroy, D., & Parke, A. (2018). Negative experiences of non-drinking college students in Great Britain: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 16(3), 737–750.

- Katainen, A., & Härkönen, J. (2018). Miten suomalaiset perustelevat raittiuttaan? In P. Mäkelä, J. Härkönen, T. Lintonen, C. Tigerstedt, & K. Warpenius (Eds.), Näin Suomi juo – Suomalaisten muuttuvat alkoholinkäyttötavat (pp. 214–224). Helsinki: Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos.

- Katainen, A., & Rolando, S. (2015). Adolescents’ understandings of binge drinking in Southern and Northern European contexts – cultural variations of ‘controlled loss of control’, Journal of Youth Studies, 18(2), 151–166, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2014.933200

- Koponen, P., Borodulin, K., Lundqvist, A., Sääksjärvi, K., & Koskinen, S. (2018). Terveys, toimintakyky ja hyvinvointi Suomessa. FinTerveys 2017-tutkimus. THL.

- Kraus, L., Eriksson Tinghög, M., Lindell, A., Pabst, A., Piontek, D., & Room, R. (2015). Age, period and cohort effects on time trends in alcohol consumption in the Swedish adult population 1979–2011. Alcohol and Alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire), 50(3), 319–327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agv013

- Kuntsche, E., Rehm, J., & Gmel, G. (2004). Characteristics of binge drinkers in Europe. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 59(1), 113–127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.009

- Livingston, M., Raninen, J., Slade, T., Swift, W., Lloyd, B., & Dietze, P. (2016). Understanding trends in Australian alcohol consumption – an age-period-cohort model. Addiction, 111(9), 1590–1598.

- Mäkelä, P. (2018). Miten käyttötavat ovat muuttuneet? In P. Mäkelä, J. Härkönen, T. Lintonen, C. Tigerstedt, & K. Warpenius (Eds.), Näin Suomi juo – Suomalaisten muuttuvat alkoholinkäyttötavat (pp. 26–38). Helsinki: Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos.

- Mäkelä, P., & Maunu, A. (2016). Come on, have a drink: The prevalence and cultural logic of social pressure to drink more, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 23(4), 312-321, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2016.1179718

- Mäkelä, P., & Warpenius, K. (2020). Night-time is the right time? Late night drinking in Finnish public and private settings. Drug and Alcohol Review, 39(4), 321–329.

- Maunu, A. (2014). Yöllä yhdessä. Yökerhot, biletys ja suomalainen sosiaalisuus. University of Helsinki: Faculty of Social Sciences.

- Meng, Y., Holmes, J., Hill-McManus, D., Brennan, A., & Meier, P. (2014). Trend analysis and modelling of gender-specific age, period and birth cohort effects on alcohol abstention and consumption level for drinkers in Great Britain using the General Lifestyle Survey 1984-2009. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 109(2), 206–215. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12330

- Monk, R., & Heim, D. (2014). A systematic review of the Alcohol norms literature: A focus on context. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 21(4), 263–282. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2014.899990

- Nairn, K., Higgins, J., Thompson, B., Anderson, M., & Fu, N. (2006). It’s just like the teenage stereotype, you go out and drink and stuff’: Hearing from young people who don’t drink. Journal of Youth Studies, 9(3), 287–304. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260600805655

- Nash, S. G., McQueen, A., & Bray, J. H. (2005). Pathways to adolescent alcohol use: Family environment, peer influence, and parental expectations. Journal of Adolescent Health, 37(1), 19–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.06.004

- Paton-Simpson, G. (2001). Socially obligatory drinking: A sociological analysis of norms governing minimum drinking levels. Contemporary Drug Problems, 28(1), 133–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/009145090102800105

- Piacentini, M., & Banister, E. (2009). Managing anti-consumption in an excessive drinking culture. Journal of Business Research, 62(2), 279–288. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.01.035

- Raitasalo, K., & Holmila, M. (2005). The role of the spouse in regulating one’s drinking. Addiction Research & Theory, 13(2), 137–144. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/16066350512331328140

- Regan, D., & Morrison, T. G. (2013). Adolescents’ negative attitudes towards non-drinkers: A novel predictor of risky drinking. Journal of Health Psychology, 18(11), 1465–1477.

- Rinker, D. V., & Neighbors, C. (2013). Reasons for not drinking and perceived injunctive norms as predictors of alcohol abstinence among college students. Addictive Behaviors, 38(7), 2261–2266. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.02.011

- Romo, L., Dinsmore, D., Connolly, T., & Davis, C. (2015). An examination of how professionals who abstain from alcohol communicatively negotiate their non-drinking identity. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 43(1), 91–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2014.982683

- Scambler, G. (2004). Re-framing stigma: Felt and enacted stigma and challenges to the sociology of chronic and disabling conditions. Social Theory & Health, 2(1), 29–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.sth.8700012

- Simpura, J. (1983). Drinking contexts and social meanings of drinking. The Finnish Foundation for Alcohol Studies.

- Supski, S., & Lindsay, J. (2017). There’s something wrong with you’: How. Young People Young, 25(4), 323–338. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308816654068

- Thrul, J., Labhart, F., & Kuntsche, E. (2017). Drinking with mixed-gender groups is associated with heavy weekend drinking among young adults. Addiction, 112(3), 432–439. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13633

- Tigerstedt, C., Agahi, N., Bye, E., Ekholm, O., Härkönen, J., Juel Lau, C., Mäkelä, P., Moan, I. S., Parikka, S., Raninen, J., Jensen, H. A. R., Vilkko, A., & Bloomfield, K. (2020). Comparing older people’s drinking habits in four Nordic countries – summary of the thematic issue. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 37(5), 434–443. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1455072520954326

- Vashishtha, R., Pennay, A., Dietze, P., Marzan, M. B., Room, R., & Livingston, M. (2021). Trends in adolescent drinking across 39 high-income countries: Exploring the timing and magnitude of decline. European Journal of Public Health, 31(2), 424–431. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckaa193

- World Health Organisation. (2018). Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. WHO.

- Yearbook of alcohol and drug statistics 2020. (2021). Official Statistics of Finland.

Appendix 1.

Other person’s attitudes toward abstinence

When you think about the last 12 months, how often has the following occurred?:

You have been pressured to drink alcoholic beverages even if it has become evident that you do not drink.

You have been prompted to explain or justify why you do not drink.

No proper nonalcoholic alternative to alcoholic beverages has been available.

You have decided not to attend an event because it will serve alcohol.

You have tried to hide that you do not drink.

You have felt like an outsider in a situation where others consume alcohol.

You have felt that others are avoiding you because you do not drink.

You have ended up in an argument because you do not drink (no matter who started the argument).

You have experienced problems in your social relationships because you do not drink.

Response categories:

Often

Occasionally

Seldom

Never