Abstract

Background: A minority of all with alcohol use disorders seek treatment. In Denmark, a media campaign, “RESPEKT,” has been broadcast nationwide since 2015. The campaign is unique from an international perspective and aims to increase treatment-seeking. Similar interventions have, up until now, not been scientifically evaluated.

Aim: To investigate campaign awareness, understanding, attitudes, and information-seeking pre- and post the campaign period. Also, associations to demographic factors and year of campaign will be investigated.

Method: Study design: Repeated cross-sectional study

Participants: Adults aged 30–70 years, in total n = 9169.

Data: Pre- and post the campaign period between 2017 and 2020, an online questionnaire was administered by a market research company. The questionnaire covered demographic data, campaign awareness, understanding, attitudes, and information-seeking about treatment for alcohol use disorders. In addition, complete-case logistic regression was performed to model dichotomous outcomes, and odds ratios were calculated.

Results: Campaign awareness varied between 8 and 40% over the different years. Understanding of the main message was high and received higher endorsements over the study period. A majority expressed positive attitudes toward the campaign and support for the main message regarding free treatment. However, very few self-reported seeking information about AUD treatment. Female sex was associated with higher awareness of the campaign, higher understanding and more positive attitudes toward the campaign.

Conclusion: The campaign evoked positive attitudes and had an impact on increasing knowledge and changing attitudes. However, no effect on self-reported information seeking about treatment was found.

Background

Alcohol use is one of the world’s leading causes of disability and mortality (GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators, Citation2016). Several interventions on the general population level effectively reduce alcohol use and related harm (Knox et al., Citation2019), albeit not always easy to implement. Information via mass media is both a population level strategy for distributing public health messages and easily implemented. The advantage is that mass media can reach a large proportion of the population, thus potentially creating an impact on a population level. Furthermore, mass media campaigns may be run by NGO organizations that work independently of political and economic interests.

Mass media campaigns and change of health behaviors

Mass media campaigns can effectively change health behaviors, if a campaign is widespread and in a context of a more comprehensive approach with policy and available programs to support behavior change (Wakefield et al., Citation2010). More specifically, mass media campaigns have been found effective in reducing sedentary behaviors (Stead et al., Citation2019) and improving diet (Wakefield et al., Citation2010). The evidence is mixed for smoking reduction (Bala et al., Citation2017; Langley et al., Citation2014) and increase in physical activity (Abioye et al., Citation2013; Stead et al., Citation2019).

A review of mass media campaigns aimed at reducing alcohol-related harm showed that recall of the campaigns could be high (Young et al., Citation2018). The campaigns were associated with increased knowledge about and change in attitudes toward alcohol use, but no associations were seen regarding the reduction of actual alcohol use. Over 70 mass media campaigns have been conducted to reduce alcohol related harm (Dunstone et al., Citation2017), but only 24 were reported in scientific journals (Young et al., Citation2018).

Mass media interventions to increase treatment seeking

Alcohol use disorders (AUD) have one of the largest gaps between the number of individuals affected and the number of individuals in treatment (Kohn et al., Citation2004; Degenhardt et al., Citation2017). In Denmark, treatment services for AUD are readily available, but only few individuals still seek treatment (Schwarz et al., Citation2018). Therefore, it is important to improve treatment coverage in order to reduce alcohol related harm. Mass media campaigns may be one way to facilitate treatment-seeking behaviors since mass media campaigns have been suggested to be more effective in increasing behaviors that happen on specific occasions rather than behaviors that occur continuously (Stead et al., Citation2019; Wakefield et al., Citation2010). Since treatment-seeking only happens on specific occasions, it might be a behavior suitable to target via mass media campaigns, rather than trying to directly influence habitual alcohol use that can be more complex to change. A Cochrane review, (Grilli et al., Citation2002) investigated the effects of both mass media campaigns and unplanned mass media coverage on health service utilization, showing a positive trend toward mass media influencing treatment-seeking. To our knowledge, only two mass media campaigns with the aim of increasing treatment utilization for substance use have been evaluated this far: “the Scottish Health Education Unit’s 1976 campaign on Alcoholism” (Plant et al., Citation1979) and a pilot evaluation of a media intervention to increase the number of calls to a telephone helpline for fetal alcohol syndrome in New Jersey, the United States of America (Awopetu et al., Citation2008). Both campaigns showed a positive effect on treatment-seeking. This suggests that mass media can play a role in treatment-seeking behaviors. However, newer studies are needed, especially as mass media communication has evolved significantly during the past decades.

Hypothesized mechanism of change

Stead et al. (Citation2019) have developed a logic model, which identifies recall of the campaign, understanding of the campaign message and attitudinal and emotional responses to the campaign as important factors in a causal pathway of change. These factors can, in turn, increase knowledge, awareness, attitudes, and motivation associated with information-seeking about treatment and, in turn, treatment-seeking behaviors (

Graph 1. Logic model of mechanism of change (Stead et al., Citation2019).

Graph A2. Understanding.

Proportions of participants endorsing understanding of the campaign message.

Mechanisms of change can differ in their effectiveness depending on the target group. One important factor is socioeconomic factors. These are associated with harm from alcohol – individuals with lower socioeconomic position (SEP) are at higher risk of alcohol-related harm than those with higher SEP (Jones et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, mass media campaigns for other modifiable risk factors show less effectiveness among individuals with lower SEP (De Bourdeaudhuij et al., Citation2011; Niederdeppe et al., Citation2008). This highlights the importance of taking sociodemographic variables into account when evaluating interventions.

RESPEKT campaign

The Danish organizations Alkohol & Samfund and Trygfonden, in close cooperation with media agency Hjaltelin Stahl, PR agency Crosstown and local alcohol treatment services, developed a cross media campaign, “RESPEKT,” which has been broadcast annually across Denmark since 2015. The overall aims of the campaign were to:

Increase the knowledge that the council offers treatment for AUD free of charge

Increase the number of individuals who seek treatment and advice for AUD in the council treatment centers

Increase the number of individuals who initiate treatment for AUD.

The campaign is a targeted health communication approach (Kreuter & Wray, Citation2003) where men in the general population age 40 to 70 years old with AUD are a primary target group, since it was considered the largest group of non-treatment-seeking individuals with AUD. Secondary target groups were spouses, children, friends, colleagues, and supervisors of individuals with AUD.

The campaign is multi-component, where the main activities are TV and Internet advertisements and local activities in cooperation with the councils. The campaign also includes posters and pamphlets distributed via social media and in public places, in addition to short movies. The advertisements provide information about a web page with further details. The TV campaign calls to action and encourages the viewers to “Take the first step.” The length of the campaign has varied between the years; in 2017, it was 42 days long; in 2018, it was 60 days; in 2019, it was 36 days and in 2020, seven days.

The content of the main campaign film varied over the years. From 2016 to 2018 the film showed children in a football dressing room, where a child proudly told his friends that his father had stopped drinking. The film ended with father and son hugging, and the message “it gives respect to do something about your alcohol problem.” In 2019, the film showed a child at home, cleaning up beer cans while the father was asleep on the living room sofa. The boy made sandwiches for the father and wrote the telephone number of the national telephone help line for AUD on a post-it note to his father, before leaving home. The overall message is that those who help, should be helped. In 2020, the football dressing room film was shown again, mainly at cinemas. However, due to Covid-19 restrictions, it was only shown very few times ().

Table 1. Demographic.

The RESPEKT campaign is unique from an international perspective, aiming to increase treatment-seeking and its repeated exposure annually since 2015. Similar interventions have, up until now, not been scientifically evaluated. Although the primary target group of the campaign was men aged 40 to 70, there is a need to study which groups in society this type of intervention may impact, since the campaign also aims to increase treatment-seeking among women, and awareness of alcohol problems and possibilities of receiving help on a more general level, e.g., from relatives, spouses, colleagues etc.

Aim

The overall aim of this study is to investigate the impact of the RESPEKT campaign between 2017 and 2020.

Specifically, the study will investigate awareness of the campaign, understanding of the campaign message, and attitudes toward the campaign, measured pre-and-post the campaign period. The analyses will take demographic factors; age, sex, education, having children, domicile, and year of the campaign into consideration. Further, for those exposed to the campaign, information-seeking about treatment for AUD will be analyzed, also in relation to demographic factors and year of the campaign.

Method

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the University of Southern Denmark on the 14th of January 2021, registration number: 20/70424. The approval allowed use of data, already collected by a marketing research company, see below.

Study design

Repeated cross-sectional study

Participants

The participants were recruited by a market research company with access to a panel consisting of adults from all regions in Denmark. A couple of weeks pre-and-post the campaign period between 2017 and 2020, a representative group of adults aged 30–70 years were asked to participate in an online questionnaire. The topic of the survey was not known to the participants beforehand. In 2020, the proportion of participants that dropped out before completing the survey was a bit higher compared to similar surveys on other topics: 8.5% compared to normally 5–6%. In total 9169 individuals participated in an either pre- or-post survey during the study period.

Outcome

The outcomes are campaign awareness, understanding, attitudes toward the campaign, and information-seeking about treatment for AUD.

Measurements

The questionnaire covered demographic data on sex, age category, education, having children, and region of domicile. Moreover, the questions regarding the campaign were either dichotomous yes/no, or on an ordinal scale: highly disagree; disagree; neither agree nor disagree; agree respectively highly agree. For the present study, ordinal variables were recoded to dichotomous outcomes. Specifically, “agree” and “highly agree” were grouped into one category, reflecting a positive statement to the item, and “highly disagree,” “disagree,” and “neutral” into the second category, representing a neutral to negative statement.

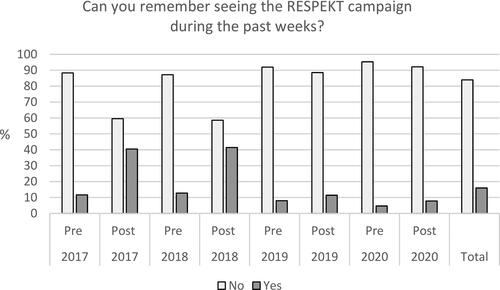

In both the pre- and post-campaign survey, the item covering campaign awareness was: “Can you remember seeing the RESPEKT campaign during the past weeks?” (dichotomous). Although it would be expected that participants would answer “no” to this item in the pre campaign survey, it should be noted that the participants might endorse being exposed to the campaign during previous years. After measuring awareness of the campaign, the participants were shown the campaign film and then asked questions about their understanding of the campaign message, attitudes toward the campaign and motivation to seek further information about treatment of AUD.

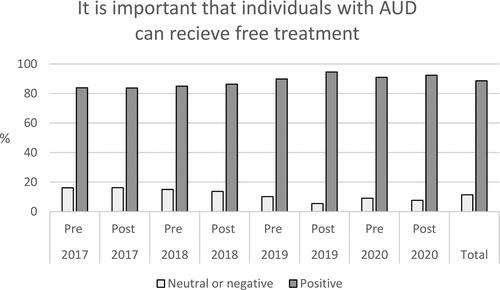

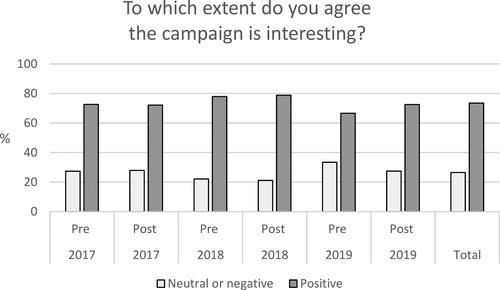

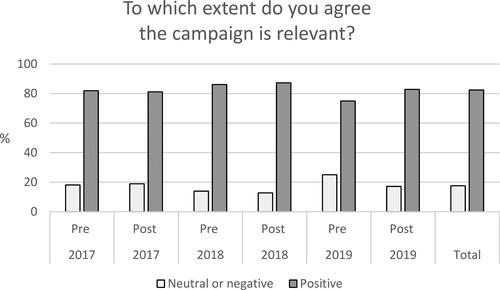

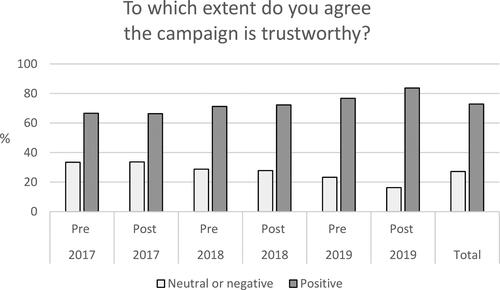

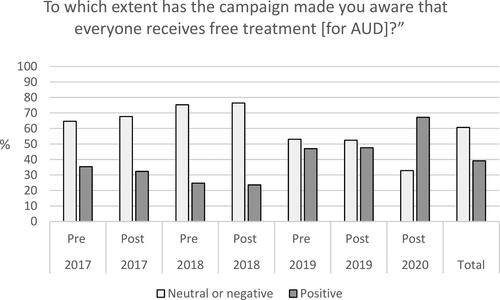

Understanding of the campaign message was measured with: “To which extent has the campaign made you aware that everyone receives free treatment [for AUD]?” (ordinal). This item was not included at the pre-campaign measure in 2020. The items covering attitudes toward the campaign were: “It is important that individuals with AUD can receive free treatment.” (dichotomous); “To which extent do you agree the campaign is interesting?” (ordinal); “To which extent do you agree the campaign is relevant?” (ordinal); “To which extent do you agree the campaign is trustworthy?” (ordinal). The items covering “interesting,” “relevant” and “trustworthy” were not included in 2020.

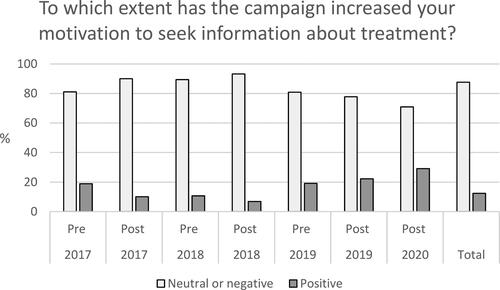

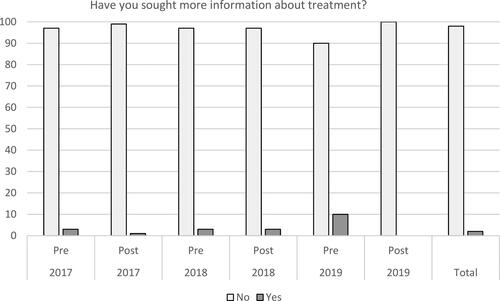

Participants who endorsed seeing the campaign were asked items covering information-seeking for treatment of AUD: “To which extent has the campaign increased your motivation to seek information about treatment [for AUD] at Alkolinjen (Alkolinjen is the Danish national telephone helpline and information webpage)?” (ordinal) and “Have you sought more information about treatment [for AUD] at Alkolinjen?” (dichotomous). The items regarding motivation to seek information was not included in the survey pre the campaign year 2020, and information-seeking was not included at all in 2020. Please see appendix, , for an overview of the included questions each year.

Table A1. Overview of questions included each year.

Data analyses

After describing the sample, complete-case logistic regression was performed in order to model dichotomous outcomes. Odds ratios (OR) were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

The analyses were performed in two steps. First, the crude associations between each exposure variable: measurement pre- or- post the campaign period, socio-demographic factors, and year of campaign, were calculated. Next, all analyses were adjusted for pre- or- post campaign measure, sex, age category, education, having children, region of domicile, and year of data collection. All analyses were carried out using Stata MP 16.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) ().

Table 2. Characteristics of the campaign the different years.

Results

There were missing data on the following variables: education (4%), children (4.6%) and region (0.7%) ( and ).

Table 3. Proportions (%) of participants endorsing each question each year.

To which extent do you agree the campaign is interesting?

To which extent do you agree the campaign is trustworthy?

Table 4. Odds ratios (OR) for awareness of the campaign, understanding and attitudes towards the campaign.

Campaign awareness

Participants in the post-campaign measure had three times higher odds of endorsing seeing the campaign (adjusted OR (AOR) 3.37, 95% CI (2.95;3.85)) compared to participants in the pre-campaign survey (). Women were slightly more aware of the campaign than men (AOR 1.33; 95% CI (1.17;1.51)). Compared to 2017, participants in 2019 and 2020 reported having seen the campaign at a much lower degree (2019: AOR .26, 95% CI (.21; .31); 2020: AOR .19, 95% CI (.16; .24)).

Understanding of campaign message

Women had a nearly 50% higher odds of being aware of the main message about free treatment for AUD (AOR 1.46; 95% CI (1.30;1.68)). Having more than 12 years of education compared to less than 9 years slightly decreased the rate of awareness (AOR .80; 95% CI (.68;.94)). Awareness of the main message varied over the different years, where 2018 compared to 2017 showed lower awareness of the main message (AOR .61; 95% CI (.52;.70)). On the contrary, participants had 70% higher odds of being aware of the main message in 2019 (AOR 1.70; 95% CI (1.46;1.97)), and nearly four times higher odds in 2020 (AOR 3.98; 95% CI (3.30;4.79)) compared to 2017.

Attitude toward the campaign

Women had 50% higher odds of having a positive attitude toward the campaign message (AOR 1.57; 95% CI (1.32;1.80)), and higher age also slightly increased the likelihood of a positive attitude (40–49 years: AOR 1.45; 95% CI (1.15;1.84); 50–70 years: AOR 1.37; 95% CI (1.11;1.69). Furthermore, odds of a positive attitude were over twice as high both in 2019 (AOR 2.59; 95% CI (2.10;3.24)) and 2020 (AOR 2,26; 95% CI (1.87;2.73)) compared to 2017.

Women (AOR 1.67; 95% CI (1.48; 1.89)), participants with children (AOR 1.46; 95% CI (1.26; 1.69)), and participants who participated in 2018 (AOR 1.38; 95% CI (1.18; 1.60)) had a higher likelihood of endorsing the campaign as “interesting.” However, in 2019 the odds of finding the campaign “interesting” was slightly lower than in 2017 (AOR .82; 95% CI (.70; .95)) ().

Table 5. Odds ratios (OR) for attitudes towards the campaign and information seeking.

Attitude toward the campaign

Women had significantly higher odds of endorsing the campaign both as “relevant” (AOR 1.89; 95% CI (1.64; 2.19)) and “trustworthy” (AOR 1.71; 95% CI (1.51; 1.94)) (). The same pattern was seen for participants with children; “relevant” (AOR 1.34; 95% CI (1.13; 1.59); “trustworthy”: AOR 1.35; 95% CI (1.16; 1.57)) and participants in the age group of 50 years and above compared to those between 30 and 39 years (“relevant” AOR 1.38; 95% CI (1.10; 1.74); “trustworthy”: AOR 1.48; 95% CI (1.21; 1.81)). Participants in 2018 had higher odds of endorsing the campaign as both “relevant” (AOR 1.49; 95% CI (1.24; 1.78)) and “trustworthy” (AOR 1.27; 95% CI (1.10; 1.46)) compared to 2017. In 2019 this was only the case for “trustworthy” (AOR 2.14; 95% CI (1.82; 2.52)).

Information seeking for treatment of alcohol use disorders

Vocational training (AOR .52; 95% CI (.29; .92)) or more than 12 years of education (AOR .41; 95% CI (.25; .70)) was associated with significantly lower odds of motivation to seek information compared to less than 9 years of education (). Participating in the survey after the campaign period lowered the odds of being motivated to seek information (AOR .62; 95% CI (.39; .99)). The odds of being motivated to seek information was also lower in 2018 (AOR .60; 95% CI (.37; .97)) compared to 2017, however, in 2020 significantly higher (AOR 3.57; 95% CI (1.87; 6.80). Participants 50 years and older had lower odds of actually seeking information (AOR .23; 95% CI (.07; .76)) compared to those aged 30–39 years. Finally, participating in the survey after the campaign period lowered the odds of seeking information about treatment (AOR .35; 95% CI (.16; .80)).

Discussion

Awareness of the campaign varied between the different years during the study period, with the highest endorsements of having seen the campaign at the post campaign measure in 2017 and 2018. During these two years, 40% of the participants had seen the campaign, while the corresponding number in 2020 was only 8%. The low awareness of the campaign in 2020 is probably due to covid-19, where restrictions and competing media attention contributed to low exposure of the campaign film at cinemas. A different possible contributing factor for the differences in awareness between the years, is that the length of the campaign and the campaign budget varied over the years. In 2017 and 2018, the campaign lasted a longer period of time, and the budget was higher. A prime-time TV campaign was also included, which possibly could have had a higher breakthrough to the population. Previous studies of mass media campaigns for other health behaviors than alcohol, are inconclusive whether the type of media channels used contribute to the effectiveness (Stead et al., Citation2019). There is instead evidence that longer duration and greater intensity are associated with higher effectiveness. The differences in awareness between the years of the RESPEKT campaign can, thus, be related to longer duration and higher intensity in certain years, rather than the type of media channels used. The results highlight the need for a sizeable budget for mass campaigns to increase the probability of a breakthrough on a population level.

In contrast to awareness of the campaign, the understanding of the main message about free treatment for AUD received higher endorsements in 2019 and 2020 compared to 2017 and 2018. However, in total, understanding the main message was only endorsed by 39% of the participants. The differences between the years might be explained by the change of topics of the films shown during the campaign. The first film described how a father who had stopped drinking was viewed with respect from his son, while the latter focused on the strain that is put on children of parents who drink. Women showed higher understanding of the main message about free treatment than men. This is in contrast to an earlier Danish study, which investigated the effects of a media campaign on knowledge about risk drinking levels (Grønbaek et al., Citation2001). Here, men showed higher knowledge about drinking limits compared to women.

Overall, the participants expressed positive attitudes toward the campaign. The support for the main message about free treatment increased during the study period and received higher support in the two latter years compared to the two initial years. A majority also endorsed the campaign as highly interesting, relevant, and trustworthy. The strengthened support for free treatment is in line with previous studies, where mass media campaigns have been associated with increased knowledge and change in attitudes (Young et al., Citation2018). This is also in line with the logic model (Stead et al., Citation2019) described in the introduction. Changes in attitudes can possibly strengthen the support for other public health measures with the aim of reducing alcohol-related harm in society and can also be a moderating factor in the mechanism of change for initiating treatment-seeking. Mass media campaigns can also contribute to public discussions about alcohol use and treatment, which recently have been emphasized as important in order to change collective norms about alcohol use in society (McCambridge, Citation2021).

Information-seeking showed lower endorsements compared to awareness of the campaign, understanding of the campaign message and attitudes, which is expected following the logic model presented (Stead et al., Citation2019). However, very few participants of those, who had actually seen the campaign before the survey, reported having sought further information about treatment for AUD. Unexpectedly, there were higher endorsements of information-seeking about treatment for AUD in the pre-campaign survey than in the post campaign survey, probably referring to having seen the campaign the previous years. An additional explanation may be that the post campaign survey was performed only a few weeks following the campaign, thus the time period was too brief to measure any changes in information seeking. Another possible explanation may be recall bias; those where the campaign had an impact on motivation and information seeking, could be more likely to remember and endorse having seen the campaign.

In contrast to the results from the other outcome measures, where women rated higher awareness, higher understanding, and more positive attitude toward the campaign, there were no gender differences in self-reporting seeking information about treatment for AUD. AUD is more common among men compared to women, and a majority of treatment-seekers for AUD in Denmark are men, which may influence the results (Schwarz et al., Citation2018). Men was the target group of the campaign, and the campaign films also portrayed men, specifically men as fathers. Overall, participants with children expressed more positive attitudes toward the campaign compared to those without children, which probably is associated with the focus on children and parenthood in the campaign. Identification with the message and the spokesperson of the media attention has been found important in other studies (Garnett et al., Citation2021).

However, considering the consistently more positive association between the female sex and the other outcome measures, this finding is contraindicative of the assumed change mechanism according to the logic model (Stead et al., Citation2019), described above. The model hypothesizes that higher awareness, higher understanding, and more positive attitude toward the campaign would be associated with higher rates of information-seeking. One possible explanation may be that women suffer to a greater extent than men from the harm of others drinking (Bloomfield et al., Citation2019). This could contribute to women expressing more positive attitudes toward the campaign, but not reporting having sought information about treatment. Another plausible explanation is the stigma associated with AUD (Kilian et al., Citation2021). Stigma can reduce the willingness to self-report this type of behavior, also in anonymous surveys (Andreasson et al., Citation2013). Stigma can delay treatment-seeking, and it affects women to a higher degree compared to men (Wallhed Finn et al., Citation2014), which could skew results based on self-report.

Opposite to previous studies (De Bourdeaudhuij et al., Citation2011; Niederdeppe et al., Citation2008), the present study found no association between educational level and attitudes toward the campaign. However, individuals with lower education showed higher endorsements of understanding the campaign message and higher motivation to seek information about treatment.

Participants aged 50 years and younger were, compared to older, more likely to self-report information-seeking about treatment for AUD. This is equivalent to the previous Danish study about awareness of alcohol risk levels, where younger participants also increased their knowledge to a higher degree than older participants (Grønbaek et al., Citation2001). However, for other health behaviors such as tobacco and physical activity, age has not been found to be associated with the effectiveness of mass media campaigns (Abioye et al., Citation2013; Bala et al., Citation2017).

Overall, the campaign can be considered successful in evoking positive attitudes and strengthening the support for free treatment for AUD. However, the awareness varied between the years, and the understanding of the main message was lower than expected. Also, self-reported information-seeking for treatment of AUD was very low. There may be a need for additional or a different targeted message in order to increase the understanding of the main message and increase information-seeking behaviors. Targeted communication, used in the RESPEKT campaign, may be especially relevant for uniform target groups (Kreuter & Wray, Citation2003). The low numbers of self-reported information-seeking could indicate that individuals with AUD are such a heterogeneous group, that different campaign messages are needed in order to reach the whole spectrum of individuals. Coming to the decision and seeking treatment for AUD is a complex behavior, where also perceptions of attractiveness of treatment play an important role (Ritter et al., Citation2019; Wallhed Finn et al., Citation2014). However, as there is no data on the participants’ alcohol use, the low self-reported information-seeking for AUD may reflect that there is no need for treatment, or that there is an unmet need.

Strengths and limitations

The main limitation is the cross-sectional study design, where it is not possible to draw conclusions about causality. Using a market research panel for recruiting participants can lead to an increased risk for selection bias, specifically not reaching vulnerable groups. For transparency, the sample is described as detailed as possible with the available data. Moreover, there is no data on the participants’ alcohol use. Also, the items varied slightly between the years. Another limitation is the use of self-reported behaviors and that very few endorse information-seeking, which leads to uncertainty for those estimates. In future studies, we suggest the use of objective data from national registers in order to measure treatment-seeking behaviors. Also, future studies should include relevant information, such as alcohol use, to ensure that the target group for the campaign is reached, and how they respond.

One strength is the repeated survey over a four-year period, which also contributes to the large sample size. This is, to the best of our knowledge, unique in an international comparison and the study contributes to developing the knowledge for this type of intervention.

Conclusions

Awareness of the campaign varied over the different years during the study period, and that the awareness seems sensitive to budget and length of the campaign. The campaign evoked positive attitudes and may have an impact on increasing knowledge and changing attitudes. However, the campaign had no effect on self-reported information-seeking about treatment. We suggest that future studies use objective data to measure treatment seeking behaviors.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abioye, A. I., Hajifathalian, K., & Danaei, G. (2013). Do mass media campaigns improve physical activity? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Public Health, 71(1), 20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/0778-7367-71-20

- Andreasson, S., Danielsson, A. K., & Wallhed-Finn, S. (2013). Preferences regarding treatment for alcohol problems. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 48(6), 694–699. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agt067

- Awopetu, O., Brimacombe, M., & Cohen, D. (2008). Fetal alcohol syndrome disorder pilot media intervention in New Jersey. Canadian Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 15, 134–131.

- Bala, M. M., Strzeszynski, L., & Topor-Madry, R. (2017). Mass media interventions for smoking cessation in adults. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11, CD004704. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004704.pub4

- Bloomfield, K., Jensen, H. A. R., & Ekholm, O. (2019). Alcohol’s harms to others: the self-rated health of those with a heavy drinker in their lives. European Journal of Public Health, 29(6), 1130–1135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz092

- De Bourdeaudhuij, I., Simon, C., De Meester, F., Van Lenthe, F., Spittaels, H., Lien, N., Faggiano, F., Mercken, L., Moore, L., & Haerens, L. (2011). Are physical activity interventions equally effective in adolescents of low and high socio-economic status (SES): results from the European Teenage project. Health Education Research, 26(1), 119–130. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyq080

- Degenhardt, L., Glantz, M., Evans-Lacko, S., Sadikova, E., Sampson, N., Thornicroft, G., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Al-Hamzawi, A., Alonso, J., Helena Andrade, L., Bruffaerts, R., Bunting, B., Bromet, E. J., Miguel Caldas de Almeida, J., de Girolamo, G., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Maria Haro, J., Huang, Y., … Kessler, R. C. (2017). Estimating treatment coverage for people with substance use disorders: an analysis of data from the World Mental Health Surveys. World Psychi, 16(3), 299–307. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20457

- Dunstone K, Brennan E, Slater MD, Dixon HG, Durkin SJ, Pettigrew S, Wakefield MA. Alcohol harm reduction advertisements: a content analysis of topic, objective, emotional tone, execution and target audience. BMC Public Health. 2017 Apr 11;17(1):312.https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4218-7 PMID: 28399829; PMCID: PMC5387386

- Garnett, C., Perski, O., Beard, E., Michie, S., West, R., & Brown, J. (2021). The impact of celebrity influence and national media coverage on users of an alcohol reduction app: a natural experiment. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-10011-0

- GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators. (2016). Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet, 388(10053), 1659–1724. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8

- Grilli, R., Ramsay, C., & Minozzi, S. (2002). Mass media interventions: effects on health services utilisation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7(1) CD000389. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd000389

- Grønbaek, M., Strøger, U., Strunge, H., Møller, L., Graff, V., & Iversen, L. (2001). Impact of a 10-year nation-wide alcohol campaign on knowledge of sensible drinking limits in Denmark. European Journal of Epidemiology, 17(5), 423–427. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1013765827585

- Jones, L., Bates, G., McCoy, E., & Bellis, M. A. (2015). Relationship between alcohol-attributable disease and socioeconomic status, and the role of alcohol consumption in this relationship: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 400 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1720-7

- Kilian, C., Manthey, J., Carr, S., Hanschmidt, F., Rehm, J., Speerforck, S., & Schomerus, G. (2021). Stigmatization of people with alcohol use disorders: An updated systematic review of population studies. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 45(5), 899–911. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14598

- Knox, J., Hasin, D. S., Larson, F. R. R., & Kranzler, H. R. (2019). Prevention, screening, and treatment for heavy drinking and alcohol use disorder. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 6(12), 1054–1067. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30213-5

- Kohn, R., Saxena, S., Levav, I., & Saraceno, B. (2004). The treatment gap in mental health care. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 82(11), 858–866.

- Kreuter, M. W., & Wray, R. J. (2003Tailored and targeted health communication: strategies for enhancing information relevance. American Journal of Health Behavior, 27(Suppl 3), S227–S232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5993/ajhb.27.1.s3.6

- Langley, T., Szatkowski, L., Lewis, S., McNeill, A., Gilmore, A. B., Salway, R., & Sims, M. (2014). The freeze on mass media campaigns in England: a natural experiment of the impact of tobacco control campaigns on quitting behaviour. Addiction, 109(6), 995–1002. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12448

- McCambridge, J. (2021). Reimagining brief interventions for alcohol: towards a paradigm fit for the twenty first century?: INEBRIA Nick Heather Lecture 2019: This lecture celebrates the work of Nick Heather in leading thinking in respect of both brief interventions and wider alcohol sciences. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 16(1), 41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-021-00250-w

- Niederdeppe, J., Fiore, M. C., Baker, T. B., & Smith, S. S. (2008). Smoking-cessation media campaigns and their effectiveness among socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged populations. American Journal of Public Health, 98(5), 916–924. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.117499

- Plant, M. A., Pirie, F., & Kreitman, N. (1979). Evaluation of the Scottish Health Education Unit’s 1976 campaign on alcoholism. Social Psychiatry, 14(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00583569

- Ritter, A., Mellor, R., Chalmers, J., Sunderland, M., & Lancaster, K. (2019). Key considerations in planning for substance use treatment: estimating treatment need and demand. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 18, 22–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15288/jsads.2019.s18.22

- Schwarz, A. S., Nielsen, B., & Nielsen, A. S. (2018). Changes in profile of patients seeking alcohol treatment and treatment outcomes following policy changes. Zeitschrift Fur Gesundheitswissenschaften = Journal of Public Health, 26(1), 59–67. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-017-0841-0

- Stead, M., Angus, K., Langley, T., Katikireddi, S. V., Hinds, K., Hilton, S., Lewis, S., Thomas, J., Campbell, M., Young, B., & Bauld, L. (2019). Public health research. In Mass media to communicate public health messages in six health topic areas: A systematic review and other reviews of the evidence. NIHR Journals Library. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3310/phr07080

- Wakefield, M. A., Loken, B., & Hornik, R. C. (2010). Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. The Lancet, 376(9748), 1261–1271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60809-4

- Wallhed Finn, S., Bakshi, A.-S., & Andréasson, S. (2014). Alcohol consumption, dependence, and treatment barriers: Perceptions among nontreatment seekers with alcohol dependence. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(6), 762–769. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2014.891616

- Young, B., Lewis, S., Katikireddi, S. V., Bauld, L., Stead, M., Angus, K., Campbell, M., Hilton, S., Thomas, J., Hinds, K., Ashie, A., & Langley, T. (2018). Effectiveness of mass media campaigns to reduce alcohol consumption and harm: A systematic review. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 53(3), 302–316. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agx094