Abstract

Background

The dynamics of injection drug use and higher-risk sexual practices compound the risk of HIV and HCV acquisition. Published literature on people who inject drugs (PWID) has examined risk of infection assuming homogeneity of cohort behavior. Categorizing subgroups by injection and sexual risk can inform a more equitable approach to how syringe services programs (SSPs) adapt harm reduction resources and implementation of evidence-based interventions. We explored injection and sexual risk profiles among PWID to determine significant predictors of class membership.

Methods

Data were collected from 1,272 participants at an SSP in Miami-Dade County. Latent Class Analysis (LCA) examined how 10 injection/sexual behavior indicators cluster together to create profiles. Model fit statistics and multivariable multinomial latent class regression identified the optimal class structure and significant predictors of class membership. We assessed SSP visits, naloxone access, HIV/HCV testing and prevalence, and incidence of self-reported wounds.

Results

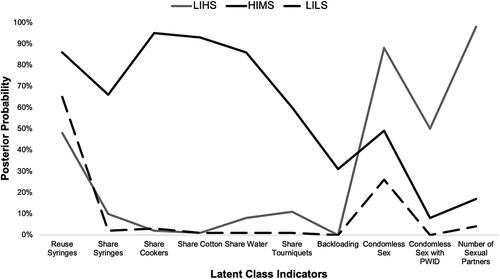

Three distinct profiles of injection/sexual risk were determined: Low Injection/High Sexual (LIHS) (9.4%); High Injection/Moderate Sexual (HIMS) (18.9%); and Low Injection/Low Sexual (LILS) (71.7%). Participants reporting gay/bisexual orientation and methamphetamine injection more likely belonged to the LIHS class. LIHS class members had higher prevalence of HIV, while those of HIMS reported increased hepatitis C prevalence. Compared to members of LILS, those of HIMS more likely experienced unstable housing, gay/bisexual orientation, heroin or speedball injection, and identifying as women. HIMS cohort members had more SSP visits, naloxone accessed, and higher wound incidence than those of LILS.

Conclusions

Understanding PWID subgroups amplifies the importance of implementing evidencebased interventions such as PrEP for those engaging in highest risk behavior, with focused interventions of antiretroviral management and access to condoms for members of the LIHS class and HCV screening with wound care for those belonging to HIMS.

Introduction

Published literature on people who inject drugs (PWID) has examined risk of infection assuming homogeneity of cohort behavior (Linton et al., Citation2015). In addition to variability of injection and sexual risk behaviors over time, PWID also comprise a spectrum of sociodemographic characteristics, accessibility to health services, and housing inequities that impact health outcomes such as HIV and HCV acquisition (Hodder et al., Citation2021; Linton et al., Citation2015). For instance, HIV outbreaks have become more common in young, White people as well as in rural areas (Alpren et al., Citation2020; Cranston et al., Citation2019; Peters et al., Citation2016; Van Handel et al., Citation2016). Syringe sharing, a risk factor of HIV, has become less prevalent among Black and Hispanic PWID while remaining stagnant among White PWID (Hodder et al., Citation2021). Inconsistent drug use patterns adds another layer of complexity, as multi-route and polysubstance use also inform risk level (Hautala et al., Citation2018). Another risk-defining behavior for HIV acquisition includes sexual practices, which several studies indicate as inseparable from injection drug use (IDU) (Brookmeyer et al., Citation2019; James et al., Citation2013). Sexual behaviors such as inconsistent use of barrier protection, exchange of sex for drugs, lack of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and multiple partners further increase risk for HIV and HCV transmission (Hautala et al., Citation2018). Variability of concurrent injection and sexual risk behaviors among PWID pose challenges in targeted prevention interventions for this diverse cohort (James et al., Citation2013).

IDU augmented by riskier sexual practices increase exposure to HIV and HCV. Syringe services programs (SSPs) are a critical evidence-based intervention to prevent infectious diseases among PWID (Fernandes et al., Citation2017; Gibson et al., Citation2001; Hurley et al., Citation1997; MacDonald et al., Citation2003; Ruiz et al., Citation2019; Strathdee & Vlahov, Citation2001). In addition to providing new, unused syringes and injection equipment, many SSPs also offer linkage to substance use disorder treatment, distribution of naloxone, screening for bloodborne infections, and other wraparound services. SSPs are a safe, cost-effective, and evidence-based harm reduction intervention that historically marginalized communities can interface at the community level (James & Jordan, Citation2018). Using the analytic tool of Latent Class Analysis (LCA), our study explored injection and sexual risk profiles among PWID participants at a Miami-Dade SSP to determine significant predictors of class membership. Uncovering latent classes of risk behavior in this participant cohort can inform a more equitable approach to adapting SSP harm reduction resources and interventions to each class, optimizing prevention of infectious diseases and fatal overdose.

Traditionally, studies that examine risk behaviors among PWID apply conventional analytic techniques, focusing on injection and sexual risk separately (Sharifi et al., Citation2017). In comparison, latent class analysis (LCA) divides a population into distinct subgroups, identifying hidden phenotypes and predictors of class membership (Jacka et al., Citation2018). Precedent LCA studies typically uncover a spectrum of risk—a low-risk cohort with modest likelihood of injection and sexual risk practices, a high-risk group with considerable likelihood of injection and sexual risk, and at least one additional class with injection and sexual risk behaviors with varied gradation (Hautala et al., Citation2018). One LCA conducted in a rural location outside San Juan, Puerto Rico divided 315 PWID into four LCA subtypes, including low risk, high injection/low sexual risk, low infection/high sexual risk, and high risk (Hautala et al., Citation2018). Similar to urban studies, the latent class groups uncovered low-, moderate-, and high-risk groups. However among rural areas, a smaller proportion of PWID comprised the higher risk group than in urban locales, citing potential geographic and cultural differences (Hautala et al., Citation2018). Puerto Rico also has a younger PWID population compared to mainland U.S., so targeted interventions to younger users was suggested (Hautala et al., Citation2018). One non-LCA study in Vancouver employed multiple logistic regression to reveal trends in drug use and sexual practices; people who use drugs and were younger than 21 years of age experienced recent alcohol binge, while those older than 21 years of age reported depressive symptoms and engaged in crack smoking and recent IDU (Hadland et al., Citation2011). A previous LCA study at the Miami SSP indicated that individuals who inject multiple substances participate in more injection and sexual risk practices and are at greater risk for HIV acquisition compared to single-substance IDU (Bartholomew, Tookes, et al., Citation2020). Bartholomew et al. revealed a three-class solution on patterns of substance use among SSP participants at the Miami SSP. An overwhelming majority of patients were in the heroin-dominant class (73.9%), compared to both methamphetamine-dominant class and heroin/cocaine class (Bartholomew, Tookes, et al., Citation2020). Noroozi et al. captured 3 classes among the PWID cohort in Tehran, Iran, including youth with methamphetamine use, youth with cannabinoid use, and adults older than 22 years of age (Noroozi et al., Citation2015). Findings included a higher number of people living with HIV who used methamphetamines, compared with those who did not use (Noroozi et al., Citation2015).

Our LCA examining PWID at the Miami-Dade SSP presents a unique opportunity to examine sexual and injection risk amid a climate of highest new HIV diagnoses in the country, diversity of substances injected, and recent implementation as the first SSP in the state of Florida (CDC, Citation2019; Iyengar et al., Citation2019). Under the authorization of the Infectious Disease Elimination Act (IDEA) passed by Florida legislature, the Miami-Dade SSP opened in December 2016. Miami, Florida, has the highest HIV incidence of any city in the United States. Miami accounts for nearly a quarter (23%) of incident cases in the state, with upwards of 27,000 people living with HIV in 2019. Between 2015 and 2019, diagnoses of HIV transmitted through IDU among men increased by 25% (CDC, Citation2019). This LCA of an SSP cohort showcases demographic factors and drug use/sexual risk patterns exclusive to PWID engaging with a newly implemented evidence-based public health intervention in Miami.

Methods

Study design and recruitment

This study analyzed baseline enrollment programmatic data (N = 1,272) collected by the IDEA SSP fixed location in Miami, Florida between December 2016 and July 2020. Included participants were age 18 years or older and completion of an interviewer-administered enrollment assessment in English or Spanish before the receipt of harm reduction services. The 42-item enrollment survey was developed by the study team and harm reduction experts to comply with state reporting requirements. IDEA SSP staff trained in standardized administration of the surveys conducted the interviews with clients in a private setting, collecting de-identified sociodemographic, drug use, and sexual behavior risk data using REDCap software (Harris et al., Citation2009). To further ensure anonymity, IDEA SSP clients were assigned a unique participant identifier upon enrollment into the program and for subsequent visits. Program participants did not receive monetary incentives for program enrollment or sharing their data. Bartholomew et al. Citation2020 presents a comprehensive overview of enrollment data collected at the IDEA SSP (Bartholomew, Onugha, et al., Citation2020). Considering the use of anonymous program data as part of routine program evaluation, the Institutional Review Board of the University of Miami concluded that this study did not involve human subjects research.

Measures

sociodemographic characteristics

Participants self-reported their age (dichotomized to greater than or equal to 30 years old vs. less than or equal to 29 years old), biological sex assigned at birth (male vs. female), race/ethnicity (Hispanic, Non-Hispanic White, or Non-Hispanic Black), educational attainment (less than high school/GED vs. greater than or equal to high school/GED), annual income (less than or equal to $14,999 vs. greater than or equal to $15,000), current housing status (experiencing unstable housing vs. stably housed), and sexual orientation (gay/bisexual vs. heterosexual).

Substance use

Participants were asked which substances they had injected in the previous 30 days. The list of potential substances included: heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, crack cocaine, speedball (a mixture of heroin and cocaine), and fentanyl. Participants were given the option to report injecting more than one substance. Due to previous data published (Bartholomew, Tookes, et al., Citation2020), five substance use indicators were included: heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, fentanyl and speedball.

Health outcomes and SSP service utilization

Health services uptake and health outcomes among participants in the program were examined. We assessed HIV/HCV testing uptake at enrollment (yes/no) and HIV/HCV seroprevalence (percent positive among those tested) at enrollment across the latent risk profiles. Participants received on-site screening with an OraQuick Advance® Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody test or Chembio SURE CHECK® HIV 1/2 Assay and OraQuick® HCV Rapid Antibody test. Respondents also self-reported their last known HIV and HCV status. Both self-reported and on-site testing results for HIV and HCV were used in the analysis. In addition, we examined SSP utilization (the number of visits to the SSP for syringe exchange), naloxone access (the number of boxes of nasal naloxone distributed), and wound incidence. Wound incidence was calculated from self-report among participants per 100 person-years over the time the participant was enrolled in the program.

Latent class indicators

Participants were asked questions regarding their injection and sexual risk behaviors, all specified to the previous 30 days. Ten binary indicators (yes/no) related to HIV or HCV acquisition (seven injection-related and three sexual-related) were used to generate and examine the latent class structure. These indicators included the following: reusing syringes, sharing syringes/needles, sharing cookers (containers used to mix and heat drugs), sharing cottons (filters), sharing sterile water, sharing tourniquets, participating in backloading (the practice of preparing the drug in one syringe and dividing into other syringes for consumption), having sex without a condom, the number of sexual partners (< =2/>2), and the number of PWID sexual partners (< =2/>2).

Statistical analysis

We utilized latent class analysis (LCA) to examine injection and sexual risk profiles among our sample. Class solutions tested ranged from a 1-class solution to a 5-class solution. Model fit statistics, such as the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC), Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), sample-adjusted Bayesian Information Criteria (SaBIC) and bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT)) were used to determine which class structure fit the data the best (See ). To address missing data in these models, we used maximum likelihood estimation (Asparouhov, Citation2016). The optimal model was determined based on the class solution with the lowest AIC and BIC indices, following proposed best practices in the application of LCA (Weller et al., Citation2020). Once the final model was selected, we performed multivariable multinomial latent class regression using the R3STEP auxiliary procedure to determine significant predictors of class membership. In addition, we compared means across classes using the Bolk, Croon, & Hagenaars (BCH) 3-step procedure to assess differences in HIV/HCV testing uptake, HIV/HCV prevalence, SSP utilization, naloxone access, and self-reported wounds. All analyses were conducted using Mplus Version 8 (Muthén & Muthen, Citation2017).

Table 2. Model Fit Statistics and Entropy for 1-Class through 4-Class models of Injection and Sexual Behavior Indicators Among PWID SSP Participants.

Results

Sample characteristics

illustrates the study sample characteristics, including socio-demographics, housing status, type of drugs used for injection, and seropositivity for HCV and HIV. A majority of participants were Non-Hispanic White and male. Although roughly half of participants reported a yearly income of less than $15,000, most (62.1%) reported having housing at the time of enrollment. With regard to drug injection, 71.3% of the sample reported heroin use, followed by cocaine (26.8%), fentanyl/carfentanil (19.5%), methamphetamine (18.4%), speedball (18.0%), and crack cocaine (8.6%). At baseline, 10% of SSP clients were reactive for HIV, while 43.0% were reactive for HCV antibody.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of PWID Participants at a Miami-Dade SSP at Enrollment, December 2016 – July 2020 (N = 1,272).

Model selection

Based on model fit indices and interpretation of the classes for each model (1–5), we selected a 3-class model of risk profiles. A comparison of fit indices, entropy, and class sample sizes can be found in . The 3-class model presented the lowest AIC (7805.19), BIC (7969.94) and sample-adjusted BIC (7868.29), suggesting that this class solution fit the data the best. Class 1, categorized as Low Injection, High Sexual risk (LIHS), was comprised of 119 adults who had low drug injection risk (i.e., no sharing of injection equipment), but participated in higher-risk sexual behavior, such as condomless sex, sex with more than 2 partners, and sex with other PWID. Class 2, categorized as High Injection, Moderate Sexual risk (HIMS), made up the second-largest profile—this subgroup had the highest rate of reusing syringes (>80%) within the previous 30 days and engaged in high rates of both sexual and injection risk. With a subgroup of 912 participants, Class 3, categorized as Low Injection, Low Sexual risk (LILS), was the largest class with participants engaging in less risk in both sexual and injection behaviors ().

Figure 1. Three Class Solution Risk Profiles of PWID Participants at a Miami-Dade SSP. The estimated posterior probabilities are graphed on class membership.

Legend. LIHS = Low-injection, High-sexual; LILS = Low-injection, Low-sexual; HIMS = High-injection, Moderate-sexual.

Predictors of latent class membership

reports the results of the multinomial regression assessing significant predictors of class membership. Those who reported gay/bisexual orientation (aOR = 5.85, 95% CI: [3.01, 11.34]) and methamphetamine injection (aOR = 4.65, 95% CI: [2.37, 9.12]) were significantly more likely to belong to the Low Injection, High Sexual risk profile compared to the Low Injection, Low Sexual risk profile. Those who reported experiencing unstable housing (aOR = 2.04, 95% CI: [1.44, 2.89]), gay/bisexual orientation (aOR = 2.21, 95% CI: [1.34, 3.64]), heroin injection (aOR = 2.76, 95% CI: [1.60, 4.78]) and speedball injection (aOR = 2.36, 95% CI: [1.54, 3.61]) were more likely to belong to the High Injection, Moderate Sexual risk profile compared to the Low Injection, Low Sexual risk profile. However, men were less likely to belong to the High Injection, Moderate Sexual risk profile compared to the Low Injection, Low Sexual risk profile (aOR = 0.66, 95% CI: [0.46, 0.96]). Those who reported gay/bisexual orientation (aOR = 2.65, 95% CI: [1.25, 5.59]) and methamphetamine injection (aOR = 4.35, 95% CI: [1.97, 9.60]) were significantly more likely to belong to the Low Injection, High Sexual risk profile compared to the High Injection, Moderate Sexual risk profile. Sexual orientation was significant among all 3 classes. Those who reported unstable housing were less likely to belong to the Low Injection, High Sexual risk profile compared to the High Injection, Moderate Sexual risk profile (aOR = 0.44, 95% CI: [0.19, 0.99]).

Table 3. Adjusted Odds Ratios from Multinomial Latent Class Regression Assessing Significant Predictors of Class Membership.

HIV/HCV prevalence, wound incidence and SSP service utilization by risk profile

In addition, infectious diseases (HIV prevalence, HCV prevalence, incidence of wounds) and SSP service utilization (visits, HIV/HCV testing, naloxone) were examined and presented in . Those in the Low Injection, High Sexual risk profile had a significantly higher prevalence of HIV compared to the High Injection, Moderate Sexual (36.1% vs. 8.1%, p < 0.001) and the Low Sexual, Low Injection risk profiles (36.1% vs. 7.7%, p < 0.001). However, those in the High Injection, Moderate Sexual risk profile had significantly higher prevalence of HCV compared to the Low Injection, High Sexual (65.5% vs. 15.9%, p < 0.001) and the Low Injection, Low Sexual risk profiles (65.5% vs. 40.5%, p < 0.001). The mean number of SSP visits (21.1 vs. 11.8, p = 0.001), boxes of naloxone (3.1 vs. 1.7, p < 0.001), and incidence of wounds (15.7 per 100 person years vs. 6.2 per 100 person years, p = 0.002) were significantly higher for those in the High Injection, Moderate Sexual risk profile compared to the Low Injection, Low Sexual risk profile.

Table 4. HIV/HCV Seropositivity, SSP Utilization, and Health-related Services Among PWID at a Miami-Dade SSP Across Latent Classes.

Discussion

Using latent class analysis, we identified three distinct injection/sexual risk behavior profiles among PWID utilizing an SSP in a high HIV-incidence city. The three classes qualitatively described relative injection and sexual risk behaviors, with the overwhelming majority of participants in the Low Injection, Low Sexual risk class. The High Injection, Moderate Sexual risk class was the most vulnerable group, with more experiencing unstable housing and higher prevalence of HCV infection, often a harbinger of HIV infection (Rickles et al., Citation2018; Van Handel et al., Citation2016). The Low Injection, High Sexual risk class had an extremely high baseline HIV prevalence of 36.1%, underscoring the importance of sexual risk behaviors in HIV transmission among PWID (Boyer et al., Citation2017; Degenhardt et al., Citation2017). Dividing subgroups by injection and sexual risk can inform implementation of targeted interventions adapted to each class within the SSP setting. For example, targeted PrEP interventions in the High Injection, Moderate Sexual risk class would be prudent due to high HCV prevalence and mechanism of transmission (i.e., syringe sharing). Likewise, given the high prevalence of HIV in the Low Injection, High Sexual risk class, increasing PrEP uptake for PWID at risk for HIV and access to antiretrovirals for PWID living with HIV is urgently needed, especially given the risk associated with condomless anal intercourse.

The PWID in the Low Injection, High Sexual risk class had the highest adjusted odds of identifying as gay/bisexual as well reporting methamphetamine use. This finding highlights the risk of chemsex within this subgroup of PWID that has been reported in the literature (Grov et al., Citation2020; Ostrow et al., Citation2009; Plankey et al., Citation2007). Transmission dynamics among men who have sex with men are complex. Sexual risk includes condomless anal intercourse, multiple sexual partners, and sex with PWID, suggesting a tight transmission network. This sexual risk did not translate to injection behaviors; PWID in the Low Injection, High Sexual risk class had the lowest HCV prevalence, suggesting that members of this class already avoid sharing injection equipment. Compared to polysubstance or heroin-only injection, people who inject predominantly methamphetamine experience a longer half-life and less frequent injection, decreasing the risk of HCV acquisition (Bartholomew, Tookes, et al., Citation2020).

The High Injection, Moderate Sexual risk group had significantly more women than the Low Injection, Low Sexual risk class. This underscores evidence that sexual fluidity in both identity and behavior among women can be impacted by their environment, including coerced sex with partners in exchange for shelter or drugs among women experiencing homelessness (Flentje et al., Citation2020). It is essential that women have representation in leadership of harm reduction groups, as women may need more specific harm reduction interventions including reproductive health resources. Women who inject drugs are vulnerable to additional harms and stigma among PWID, compounded by limited access to culturally appropriate programming (Iversen et al., Citation2015). Exclusion of women from the larger body of research involving PWID has further systematically harmed this high priority subgroup (Springer et al., Citation2015). Another salient predictor of membership to the High Injection, Moderate Sexual risk class was unstable housing. Complex syndemics of poverty, concurrent substance use disorders, and stigma highlight the need for resource allocation when serving this community of PWID (Shiau et al., Citation2020). PWID with unstable housing often inject in public and are at increased risk of HIV infection through receptive syringe sharing as well as increased risk of overdose and arrest (Hunter et al., Citation2018; Marshall et al., Citation2010; Small et al., Citation2007; Trayner et al., Citation2019). There is an urgent need for expansion of overdose prevention sites (safe consumption sites) and access to affordable housing to mitigate the risk to PWID experiencing unstable housing.

The enrollment data of PWID showcases baseline sexual and injection risk behaviors upon establishing care at our SSP. Our LCA uses data largely from the time of enrollment, which can serve as a control to compare evolution among subgroups throughout participants’ ongoing engagement with the SSP. Furthermore, standardized HIV and HCV screening of all participants during this baseline assessment captured new diagnoses. Awareness of a new diagnosis may also influence injection and sexual risk behavior over time. Analysis of participant enrollment data upon engagement with an SSP represents the precipice of highest risk behavior and likely the time point that most urgently requires focused intervention.

There are several limitations to acknowledge when interpreting the results of this study. Restricting manuscript variables to sex assigned at birth and sexual orientation variables not fully representative of the gender spectrum remains a limitation in describing sociodemographic characteristics of our cohort. Previous studies such as Flentje et al. describe sexual orientation as a multidimensional construct that remains challenging to measure and report, further complicated by fluidity of sexuality over time. Literature suggests that sexual minority people are overrepresented among those experiencing unstable housing, trauma, and substance use (Lee et al., Citation2016). This is reflected in our study, as those identifying as gay/bisexual comprise the higher risk injection and sexual risk subgroups (High Injection, Moderate Sexual and Low Injection, High Sexual risk classes). For the purposes of our study, we pose that our 3 sexual-related behavior indicators (condomless sex, number of sexual partners, and number of PWID sexual partners) more directly predict HIV/HCV acquisition. Additionally, we found that reuse of syringes was high among all 3 subgroups. Unfortunately, per state statute, Florida SSPs must operate on a one-for-one basis. Needs-based syringe distribution and statutory change is urgently needed to promote use of a new unused syringe for each injection. Another limitation is that this study was conducted at a single SSP and might not be generalizable to other SSPs in other jurisdictions. However, the study highlights the importance of the analyses herein to improve understanding of the needs of the community served and should be considered by other SSPs. For the examination of wounds, SSP visits and Narcan utilization across latent classes, we did not control for confounding such as number of visits or time enrolled in the program, and we were not able to determine loss to follow up, an important factor when estimating utilization and incidence. However, wounds were standardized by the number of months in the program and the highest incidence of wounds seen in the High Injection, Moderate Sexual risk class is consistent with the multitude of structural and social determinants that cause harm to this subgroup of PWID.

While our study used LCA methodology to demonstrate three distinct behavior profiles among PWID, this data represents a single time point measure of injection/sexual risk and may not reflect behavior change over time. Previous research from Miami has demonstrated a decrease in injection equipment sharing and reuse among those engaged in the SSP. Furthermore, class membership of participants may shift as they encounter periods of sobriety, housing, employment, sexual fluidity, or changing relationships. Data collected upon enrollment and analyzed with LCA should be interpreted with caution, as behavioral risk may not be generalizable beyond the near future. As we largely included enrollment data, we may only extrapolate findings to inform services at intake. Nevertheless, routine SSP visits remain opportunities to reassess changing behavior and to counsel on interventions catering to individuals’ needs. Analysis of cohort data over time may also guide adaptation of care services.

Conclusions

Our study reveals that in an urban cohort of PWID in the United States, there was heterogeneity in injection and sexual risk behaviors, which clustered into 3 distinct latent classes. These differing risk profiles can be used to guide the implementation of tailored evidence-based interventions based on individual needs. For example, the Low Injection, High Sexual risk class had the highest baseline prevalence of HIV. For this group, interventions designed with the input of PWID to increase access to PrEP, condoms, antiretrovirals, and screening and treatment of sexually transmitted infections could have a significant impact on health. For PWID belonging to this class, implementation at an SSP would prioritize earlier and more frequent on-site or telemedicine provider visits to increase PrEP uptake and vaccination against hepatitis A and B. Likewise, for the High Injection, Moderate Sexual risk class, tailored interventions informed by PWID and principles of harm reduction such as wound care, screening and treatment of HCV, and increased access to PrEP promote wellness in this community. SSP operationalization for PWID of the latter profile would resemble earlier provider visits to treat skin and soft tissue infections as prevention of infectious complications, safer injection practices and overdose prevention counseling, and naloxone distribution. Beyond the scope of an individual SSP, optimization of syringe coverage through reform of the state one-for-one syringe exchange policy could substantially improve access to safe drug equipment.

Additional information

Funding

Rerfences

- Alpren, C., Dawson, E. L., John, B., Cranston, K., Panneer, N., Fukuda, H. D., Roosevelt, K., Klevens, R. M., Bryant, J., & Peters, P. J. (2020). Opioid use fueling HIV transmission in an urban setting: An outbreak of hiv infection among people who inject drugs—Massachusetts, 2015–2018. American Journal of Public Health, 110(1), 37–44.

- Asparouhov, T. (2016). Missing data, complex samples, and categorical data. [Mplus Discussion].

- Bartholomew, T. S., Onugha, J., Bullock, C., Scaramutti, C., Patel, H., Forrest, D. W., Feaster, D. J., & Tookes, H. E. (2020). Baseline prevalence and correlates of HIV and HCV infection among people who inject drugs accessing a syringe services program; Miami, FL. Harm Reduction Journal, 17(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-020-00385-0

- Bartholomew, T. S., Tookes, H. E., Bullock, C., Onugha, J., Forrest, D. W., & Feaster, D. J. (2020). Examining risk behavior and syringe coverage among people who inject drugs accessing a syringe services program: A latent class analysis. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 78, 102716.

- Boyer, C. B., Greenberg, L., Chutuape, K., Walker, B., Monte, D., Kirk, J., Ellen, J. M., & Network, A. M. T. (2017). Exchange of sex for drugs or money in adolescents and young adults: An examination of sociodemographic factors, HIV-related risk, and community context. Journal of Community Health, 42(1), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-016-0234-2

- Brookmeyer, K. A., Haderxhanaj, L. T., Hogben, M., & Leichliter, J. (2019). Sexual risk behaviors and STDs among persons who inject drugs: A national study. Preventive Medicine, 126, 105779.

- CDC. (2019). HIV Surveillance Report, 2018. Retrieved November 29 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html.

- Cranston, K., Alpren, C., John, B., Dawson, E., Roosevelt, K., Burrage, A., Bryant, J., Switzer, W. M., Breen, C., Peters, P. J., Stiles, T., Murray, A., Fukuda, H. D., Adih, W., Goldman, L., Panneer, N., Callis, B., Campbell, E. M., Randall, L., … DeMaria, A. (2019). Notes from the field: HIV diagnoses among persons who inject drugs—Northeastern Massachusetts, 2015-2018. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(10), 253–254. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6810a6

- Degenhardt, L., Peacock, A., Colledge, S., Leung, J., Grebely, J., Vickerman, P., Stone, J., Cunningham, E. B., Trickey, A., Dumchev, K., Lynskey, M., Griffiths, P., Mattick, R. P., Hickman, M., & Larney, S. (2017). Global prevalence of injecting drug use and sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV in people who inject drugs: A multistage systematic review. The Lancet. Global Health, 5(12), e1192–e1207.

- Fernandes, R. M., Cary, M., Duarte, G., Jesus, G., Alarcão, J., Torre, C., Costa, S., Costa, J., & Carneiro, A. V. (2017). Effectiveness of needle and syringe Programmes in people who inject drugs—An overview of systematic reviews. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 309.

- Flentje, A., Brennan, J., Satyanarayana, S., Shumway, M., & Riley, E. (2020). Quantifying sexual orientation among homeless and unstably housed women in a longitudinal study: Identity, behavior, and fluctuations over a three-year period. Journal of Homosexuality, 67(2), 244–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1536417

- Gibson, D. R., Flynn, N. M., & Perales, D. (2001). Effectiveness of syringe exchange programs in reducing HIV risk behavior and HIV seroconversion among injecting drug users. AIDS (London, England), 15(11), 1329–1341.

- Grov, C., Westmoreland, D., Morrison, C., Carrico, A. W., & Nash, D. (2020). The crisis we are not talking about: One-in-three annual HIV seroconversions among sexual and gender minorities were persistent methamphetamine users. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 85(3), 272–279. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002461

- Hadland, S. E., Marshall, B. D., Kerr, T., Zhang, R., Montaner, J. S., & Wood, E. (2011). A comparison of drug use and risk behavior profiles among younger and older street youth. Substance Use & Misuse, 46(12), 1486–1494. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2011.561516

- Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., & Conde, J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381.

- Hautala, D., Abadie, R., Thrash, C., Reyes, J. C., & Dombrowski, K. (2018). Latent risk subtypes based on injection and sexual behavior among people who inject drugs in rural Puerto Rico. The Journal of Rural Health, 34(3), 236–245.

- Hodder, S. L., Feinberg, J., Strathdee, S. A., Shoptaw, S., Altice, F. L., Ortenzio, L., & Beyrer, C. (2021). The opioid crisis and HIV in the USA: Deadly synergies. The Lancet, 397(10279), 1139–1150. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00391-3

- Hunter, K., Park, J. N., Allen, S. T., Chaulk, P., Frost, T., Weir, B. W., & Sherman, S. G. (2018). Safe and unsafe spaces: Non-fatal overdose, arrest, and receptive syringe sharing among people who inject drugs in public and semi-public spaces in Baltimore City. International Journal of Drug Policy, 57, 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.03.026

- Hurley, S. F., Jolley, D. J., & Kaldor, J. M. (1997). Effectiveness of needle-exchange programmes for prevention of HIV infection. The Lancet, 349(9068), 1797–1800. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(96)11380-5

- Iversen, J., Page, K., Madden, A., & Maher, L. (2015). HIV, HCV and health-related harms among women who inject drugs: Implications for prevention and treatment. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 69(Suppl. 2), S176–S181. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000659

- Iyengar, S., Kravietz, A., Bartholomew, T. S., Forrest, D., & Tookes, H. E. (2019). Baseline differences in characteristics and risk behaviors among people who inject drugs by syringe exchange program modality: An analysis of the Miami IDEA syringe exchange. Harm Reduction Journal, 16(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-019-0280-z

- Jacka, B., Bray, B. C., Applegate, T. L., Marshall, B. D. L., Lima, V. D., Hayashi, K., DeBeck, K., Raghwani, J., Harrigan, P. R., Krajden, M., Montaner, J. S. G., & Grebely, J. (2018). Drug use and phylogenetic clustering of hepatitis C virus infection among people who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada: a latent class analysis approach. Journal of Viral Hepatitis, 25(1), 28–36.

- James, K., & Jordan, A. (2018). The opioid crisis in black communities. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 46(2), 404–421. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073110518782949

- James, S., McField, E. S., & Montgomery, S. B. (2013). Risk factor profiles among intravenous drug using young adults: A latent class analysis (LCA) approach. Addictive Behaviors, 38(3), 1804–1811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.09.002

- Lee, J. H., Gamarel, K. E., Bryant, K. J., Zaller, N. D., & Operario, D. (2016). Discrimination, mental health, and substance use disorders among sexual minority populations. LGBT Health, 3(4), 258–265.

- Linton, S. L., Cooper, H. L. F., Kelley, M. E., Karnes, C. C., Ross, Z., Wolfe, M. E., Des Jarlais, D., Semaan, S., Tempalski, B., DiNenno, E., Finlayson, T., Sionean, C., Wejnert, C., & Paz-Bailey, G. (2015). HIV infection among people who inject drugs in the United States: Geographically explained variance across racial and ethnic groups. American Journal of Public Health, 105(12), 2457–2465.

- MacDonald, M., Law, M., Kaldor, J., Hales, J., & Dore, G. J. (2003). Effectiveness of needle and syringe programmes for preventing HIV transmission. International Journal of Drug Policy, 14(5-6), 353–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0955-3959(03)00133-6

- Marshall, B. D., Kerr, T., Qi, J., Montaner, J. S., & Wood, E. (2010). Public injecting and HIV risk behaviour among street-involved youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 110(3), 254–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.01.022

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthen, B. (2017). Mplus user’s guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables, user’s guide. Muthén & Muthén.

- Noroozi, M., Mirzazadeh, A., Noroozi, A., Mehrabi, Y., Hajebi, A., Zamani, S., Sharifi, H., Higgs, P., & Soori, H. (2015). Client-level coverage of needle and syringe program and high-risk injection behaviors: a case study of people who inject drugs in Kermanshah. Addiction & Health, 7(3–4), 164–173.

- Ostrow, D. G., Plankey, M. W., Cox, C., Li, X., Shoptaw, S., Jacobson, L. P., & Stall, R. C. (2009). Specific sex drug combinations contribute to the majority of recent HIV seroconversions among MSM in the MACS. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 51(3), 349–355. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a24b20

- Peters, P. J., Pontones, P., Hoover, K. W., Patel, M. R., Galang, R. R., Shields, J., Blosser, S. J., Spiller, M. W., Combs, B., Switzer, W. M., Conrad, C., Gentry, J., Khudyakov, Y., Waterhouse, D., Owen, S. M., Chapman, E., Roseberry, J. C., McCants, V., Weidle, P. J., … Duwve, J. M. (2016). HIV infection linked to injection use of oxymorphone in Indiana, 2014–2015. New England Journal of Medicine, 375(3), 229–239. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1515195

- Plankey, M. W., Ostrow, D. G., Stall, R., Cox, C., Li, X., Peck, J. A., & Jacobson, L. P. (2007). The relationship between methamphetamine and popper use and risk of HIV seroconversion in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 45(1), 85–92. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180417c99

- Rickles, M., Rebeiro, P. F., Sizemore, L., Juarez, P., Mutter, M., Wester, C., & McPheeters, M. (2018). Tennessee’s in-state vulnerability assessment for a ‘rapid dissemination of HIV or HCV infection’ event utilizing data about the opioid epidemic. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 66(11), 1722–1732. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix1079

- Ruiz, M. S., O’Rourke, A., Allen, S. T., Holtgrave, D. R., Metzger, D., Benitez, J., Brady, K. A., Chaulk, C. P., & Wen, L. S. (2019). Using interrupted time series analysis to measure the impact of legalized syringe exchange on HIV diagnoses in Baltimore and Philadelphia. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 82(2), S148–S154. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002176

- Sharifi, H., Mirzazadeh, A., Noroozi, A., Marshall, B. D. L., Farhoudian, A., Higgs, P., Vameghi, M., Mohhamadi Shahboulaghi, F., Qorbani, M., Massah, O., Armoon, B., & Noroozi, M. (2017). Patterns of HIV risks and related factors among people who inject drugs in Kermanshah, Iran: A latent class analysis. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 49(1), 69–73.

- Shiau, S., Krause, K. D., Valera, P., Swaminathan, S., & Halkitis, P. N. (2020). The burden of COVID-19 in people living with HIV: A syndemic perspective. AIDS and Behavior, 24(8) 2244–2249.

- Small, W., Rhodes, T., Wood, E., & Kerr, T. (2007). Public injection settings in Vancouver: Physical environment, social context and risk. International Journal of Drug Policy, 18(1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.11.019

- Springer, S. A., Larney, S., Alam-Mehrjerdi, Z., Altice, F. L., Metzger, D., & Shoptaw, S. (2015). Drug treatment as HIV prevention among women and girls who inject drugs from a global perspective: Progress, gaps, and future directions. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 69(Suppl. 2), S155–S161. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000637

- Strathdee, S. A., & Vlahov, D. (2001). The effectiveness of needle exchange programs: A review of the science and policy. AIDScience, 1(16), 1–33.

- Trayner, K. M., McAuley, A., Palmateer, N. E., Goldberg, D. J., Shepherd, S. J., Gunson, R. N., Tweed, E. J., Priyadarshi, S., Milosevic, C., & Hutchinson, S. J. (2019). Increased risk of HIV and other drug-related harms associated with injecting in public places among people who inject drugs in Scotland: A national bio-behavioural survey. The Lancet, 394, S91. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32888-0

- Van Handel, M. M., Rose, C. E., Hallisey, E. J., Kolling, J. L., Zibbell, J. E., Lewis, B., Bohm, M. K., Jones, C. M., Flanagan, B. E., Siddiqi, A.-E.-A., Iqbal, K., Dent, A. L., Mermin, J. H., McCray, E., Ward, J. W., & Brooks, J. T. (2016). County-level vulnerability assessment for rapid dissemination of HIV or HCV infections among persons who inject drugs, United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 73(3), 323–331. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001098

- Weller, B. E., Bowen, N. K., & Faubert, S. J. (2020). Latent class analysis: A guide to best practice. Journal of Black Psychology, 46(4), 287–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798420930932