ABSTRACT

Background: The settings where we live shape our daily experiences and interactions. Social environment and physical setting characteristics may be particularly important in communal living services, such as recovery homes for alcohol and drug disorders. Objectives: This paper describes the measurement and mobilization of architectural characteristics in one type of recovery home, sober living houses (SLHs). The Recovery Home Architecture Scale (RHAS) is a 25-item measure comprised of six subscales designed to assess architecture in SLHs. Results: Using a sample of 528 individuals residing in 41 houses, we found the RHAS had good interrater reliability, factor structure, and internal consistency. The measure also showed modest construct validity. The RHAS was not associated with length of stay (LOS) but did interact with a measure of the social environment that predicted LOS, the Recovery Home Environment Scale (RHES). Conclusions: Future studies should include a more diverse sample of SLHs and assess how house management, recovery capital, and other factors work in concert with architecture.

Introduction

A variety of studies have shown that living environments have significant influences on health, well-being, and happiness (Burton, Citation2015). Places where we live also influence how we conceptualize problems and the strategies we adopt to address them. Increasingly, service providers are creating environments designed to address problems such as mental illness (Scheid, Citation2018), medical problems (Burton, Citation2015), and alcohol and drug disorders (Wittman et al., Citation2017). To be effective, the authors suggested that service providers should shape physical and social environments to respond to the goals and needs of the population served.

We suggest the characteristics of the physical environment in recovery homes and their effects on recovery outcomes have been under-recognized. Part of the problem is state licensing and other accreditation agencies have few evidence-based guidelines to draw from to develop architectural standards. Therefore, they often address physical setting issues from a health and safety perspective with limited attention to ways architecture can influence outcomes.

Wittman et al. (Citation2014, Citation2017) advocated for an “architecture of recovery” that went beyond generic design of buildings. The authors suggested that responsive architecture for recovery homes should address the needs of residents and help fulfill the stated purposes of the homes. Examples included ways that architectural features might influence goals relevant to recovery, including opportunities for social interaction, a well-maintained house and property in which residents could take pride, peer support, a sense of safety, spaces for expression of personal identity, and outdoor recreational activities.

The purpose of the current study was to take an important first step toward development of evidence-based architectural guidelines by developing a reliable and valid measure of architecture in one type of recovery home that is popular in California, sober living houses (SLHs). Drawing on the work of Wittman et al. (Citation2014, Citation2017), we wanted to understand a broad view of architecture that responded to the needs of residents. Also consistent with this work, we wanted to understand interactive effects of architecture and the social setting.

To set a context for the development of our measure, which we labeled the Recovery Home Architecture Scale (RHAS), this article begins with a description of SLHs and research on their effectiveness. We then report on recent research describing social environment effects and descriptive work on architecture in these settings. Finally, psychometric properties of the RHAS are described using a sample of 528 SLH residents.

Sober living houses

California has a large number of recovery homes in the state known as sober living houses (SLHs). They provide alcohol- and drug-free living arrangements for persons who recently completed residential treatment, are released from incarceration, are attending outpatient treatment programs, and are seeking assistance outside formal treatment (Wittman & Polcin, Citation2014). They do not provide professional services, such as counseling or treatment planning. Instead, they use a social model approach to recovery that emphasizes peer support and peer involvement in decisions affecting the household (Shaw & Borkman, Citation1990). Houses can be nonprofit or for profit, and most are financed largely from resident fees.

Because SLHs are neither licensed nor required to report their existence to any government agency, it is difficult to ascertain their exact number. However, in California, sober living house associations such as the Sober Living Network (SLN) and California Consortium of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP) report a combined membership of nearly 800 houses in the state (Wittman & Polcin, Citation2014). A recent study aimed to identify recovery residences across the country and located 10,358, with residences located in every state and Washington, D.C. (Mericle et al., Citation2022).

Management of SLHs

Oversight of house operations (e.g., payment of rent, arranging repairs, and enforcement of house rules) are conducted by SLH managers. These individuals are typically persons in recovery, and they often have experience living in a SLH as a resident before becoming a manager. Most managers live on-site in the SLH they manage, and most received some type of compensation for their work, usually a reduction in rent required to live in the house (Polcin et al., Citation2021a). The dual vantage point of manager and recovering peer enables them to shape and sustain recovery experiences for residents through peer-based daily living activities in the house. From this perspective, the main job of the house-manager is literally to manage the use of the house to support recovery—not to manage or supervise individuals living in the house. Evidence-based recommendations for ways managers can best facilitate a physical and social environment supportive of recovery represents a major gap in the literature on recovery homes.

Research on sober living houses

Early papers on SLHs were primarily descriptive commentaries presenting them as an innovative but underrecognized service modality (Wittman, Citation1989; Citation1993). More recent papers have consisted of studies showing how SLH residents make significant improvements in a number of areas, including substance use, employment, arrests, and psychiatric symptoms (Polcin et al., Citation2010; Polcin et al., Citation2018). Individual predictors of outcome included involvement in 12-step groups, substance use in the social network, and psychiatric severity (Polcin et al., Citation2010; Witbrodt et al., Citation2019).

Social environment research

Studies have also examined resident perceptions of the social environment in SLHs as predictors of outcome. A measure of the social environment, the Recovery Home Environment Scale (RHES), was found to predict length of stay (LOS) (Mahoney et al., Citation2021), recovery capital (Polcin, Mahoney, Witbrodt, & Mericle et al., Citation2020) and substance use (Polcin et al., Citation2021b). However, the strongest predictive validity was found when examining how the RHES predicted LOS. The RHES focuses on assessment of social model recovery principles in the house social environment that are central to the philosophy of recovery in SLHs (e.g., resident support, empowerment, and involvement in house operations).

Architecture research

A limited number of studies have examined the physical characteristics of human service settings, and none have assessed architecture in SLHs. Timko (Citation1996) assessed inpatient psychiatric hospitals and residential treatment programs in the community for psychiatric and substance use disorders. Programs with more social-recreational resources, space, and access to community resources had better patient outcomes. All sites focused on professional treatment services (e.g., individual counseling, group counseling, psychoeducation groups, medications, and case management). None of the sites studied were peer operated and none used a social model approach.

Other studies have more directly assessed efforts to build architecture that responded to patients’ needs for social support. For example, to achieve a comprehensive, ecopsychosocially supportive environment in psychiatric settings, Chrysikou (Citation2019) made recommendations for services to integrate medical architecture with patient involvement. The emphasis in Chrysikou’s work on patient involvement and provision of architecture that facilitated social interaction is consistent with operational goals of recovery homes. However, the settings examined were provided professional services for psychiatric disorders, not peer-based recovery home settings.

Studies of the architectural characteristics of peer operated recovery homes have been limited to descriptive and qualitative reports. For example, Wittman et al. (Citation2014) published an exemplar architectural case report of one SLH organization in Northern California operating 16 houses with published favorable outcomes (i.e., Polcin et al., Citation2010). The case report described how inspection of the houses and interviews with the owner/operator, several house managers, and a local zoning official led to identification of architectural features of the houses that were viewed as important to facilitate a recovery environment. Examples included buildings that were well maintained, spatial layouts that facilitated resident interaction, policies that allow for expression of personal identity, high quality furnishings, safety and security features, and green, outdoor areas for socialization. These descriptive findings provided important preliminary data for the new measure developed for the current study, including development of subscales and assessment of the interaction between architecture and the social environment.

Study aims

The first aim was to develop items for RHAS domains and establish psychometric properties, which included measures of reliability, factor structure, and construct validity. A second aim was to examine of how architectural characteristics were associated with LOS. We hypothesized that higher RHAS scores would be associated with longer LOS. We chose LOS as our outcome because we surmised residents living in a well-maintained and well-managed physical space would enjoy the house and want to stay longer. In addition, we expected homes with high ratings on the RHAS would be experienced as supportive of recovery and that would increase LOS. Previous research on recovery homes has shown LOS is associated with favorable substance use and other outcomes (Reif et al., Citation2014).

Consistent with previous studies of the social environment in SLHs (Mahoney et al., Citation2021; Polcin et al. (2021), we expected the RHES, would be associated with LOS. Because the social environment was associated with LOS, we surmised the physical environment (i.e., architecture) might be as well. We further hypothesized that the strongest outcomes would be when both the RHAS and RHES scales were high.

Methods

Development of the RHAS

Procedures for developing the RHAS began with the research team discussing observational and interview data from the Wittman et al. (Citation2014) study. Six domains were identified as important for responding to residents’ needs. Each domain represented a subscale on the measure. A list of potential items was developed for each subscale. These original items were pilot tested on a small sample of five houses using four raters who visited the homes, recorded observations about architecture, and interviewed house managers. Ratings were discussed among the reviewers, which resulted in elimination and modification of a limited number of items. Many items were designed to be consistent with existing standards for houses used by NARR and the SLN.

Completing architectural assessments using the RHAS required trained raters to conduct a physical inspection of the interior and exterior of the houses as well as outdoor recreation areas. In addition, raters conducted interviews with house managers to clarify how space was used to facilitate smooth functioning of the household and support for recovery. To assess inter-rater reliability, each house was rated by two field staff. The final version or the RHAS consisted of six subscales. A copy of the final version of the RHAS is available from the corresponding author.

House Maintenance consisted of five items assessing the overall appearance of the interior and exterior of the house. The assessment included provision of maintenance equipment, such as tools for cleaning and maintenance. Additional items assessed physical characteristics from the perspective of health and safety.

Safety and Security consisted of five items assessing security of the premises (e.g., entrances where visitors can be monitored, doors that are locked after hours, and appropriate lighting). Other items included designs that discourage hiding contraband (e.g., drugs in the house) and emergency protocols for fire and earthquakes.

Sociability is a 2-item subscale related to the spatial layout of the house in terms of how it facilitates or hinders social interactions. One item assesses the extent to which one room can accommodate all house residents. A second item assesses the extent to which there are open spaces accommodating ease of circulation and accidental contacts among residents.

Personal and Residence Identity consisted of four items that assessed the extent to which rooms could be personalized with photos and other items reflecting personal aspects of individual residents. In addition, the overall residence was assessed in terms distinguishing its identity as a recovery residence (e.g., plaques, awards, logos, recovery messages, etc.).

The Furnishings subscale considers four items rating furniture and fixtures, including comfort, appearance, and durability.

Outdoor Areas is comprised of five items assessing privacy, maintenance, natural feel, suitability for recreation, and suitability for socializing. If the house has no outside area, then the house would get the lowest rating, one.

Items on the RHAS subscales were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from very poor to excellent. Subscale scores were calculated using means. A total RHAS score was calculated by summing the subscale scores.

Conceptual framework

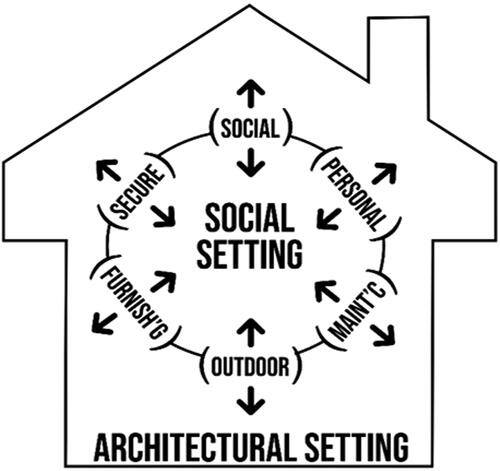

depicts a conceptual framework for understanding the RHAS domains and their reciprocal relationships with the social environment. This framing is drawn from Wittman et al. (Citation2014). That study provided the conceptual basis for most of the six subscales that went on to become the RHAS. It also described how architectural characteristics have a reciprocal relationship with the social environment, which is depicted in the figure. Each domain has an arrow pointing outward, indicating the contribution to the overall quality of the architectural setting; arrows also point inward, indicating each architectural domain influences the social environment.

Sites and participants

Goals of the study required recruitment of SLHs (N = 41) and individuals residing in them. Houses were contacted using information obtained from the SLN. To enroll a diverse sample, houses were selected to include low (24.4%), medium (51.2%) and high (24.4%) income areas. A majority of the houses (51.2%) were for men. About a quarter (24.4%) were for women and the same percentage (24.4%) were houses designed for all genders. Houses were excluded if they had children, less than 6 beds, more than 25 beds, or fees over $4,500 per month. The average number of beds per house was 14.5 (SD = 5.1) and the average rent was $810 per month. Inclusion criteria for residents were 18 years of age or older, able to provide informed consent, and had been a resident in the house for under one month. We targeted at least 25% of the sample to be women. The baseline sample consisted of 528 SLH residents. While most participants were men, we did achieve our goal of over a quarter of the sample being women (34%). Age ranged from 18 to 77 and the average age was 40 (SD = 12.5). Most participants self-identified as white (52%), followed by 16% who were African American, and 26% who were Hispanic/Latino. Slightly over half (50.5%) had some college.

Procedures

Residents entering the houses were recruited primarily by phone within one month of entering the SLHs. Baseline assessments were conducted on average 16 days (SD = 9.2) after entering the house. One month after recruitment, residents participated in an interview assessing their perceptions of the social environment (i.e., the RHES). The one-month period allowed residents to become familiar with the social environment and develop well-informed views. All study procedures were approved by the Public Health Institute IRB.

Measures

The overall RHAS and subscales were examined in relation to a variety of measures.

(1) Outcome and other resident-level measures.

Length of stay (LOS) was the primary outcome and was measured as the number of days residing in the house.

Demographic characteristics collected at baseline included age, gender, and race.

A single item from the Recovery Capital Scale developed by White (Citation2009) was used to assess construct validity: “I live in a place free of alcohol and drugs.” This item gets at one of the core purposes of good architecture in recovery homes: provision of an abstinent living environment.

The Alcohol and Drug Consequences Questionnaire (ADCQ) (Cunningham et al., Citation1997) was used as a measure of motivation. Subscales assess the benefits (14 items) and costs (15 items) of stopping/cutting down on substance use. For persons who had established abstinence, we used a modification of the scales asking about costs and benefits of maintaining abstinence (Polcin et al., Citation2015).

Addiction Severity Index Alcohol and Drug Scales (McLellan et al., Citation1992) were used to as control variables in regression models. Both scales assess problem severity in their corresponding domains using a scale ranging from 0 to 1. Both scales were log transformed due to non-normal distributions.

(2) House measures

House measures included SES of the local neighborhood, number of beds (house capacity), rent, and gender of the house. These were used as descriptive variables to depict characteristics of the houses.

(3) Social environment

Recovery Home Environment Scale (RHES) (Polcin et al., Citation2021b) consists of eight items that assess the frequency of resident activities relevant to social model recovery principles using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from not at all to a lot. Scores were calculated by summing across the 8 items. Factor analysis identified two subscales: recovery support (3 items) and recovery skills 5 items). Examples of items from recovery support included: To what extent do residents provide emotional support to one another? To what extent do residents support each other to address practical problems, such as where to find needed serves, how to find employment, and transportation? Examples of recovery skills included: To what extent do residents work a 12-step recovery program on a daily basis within the SLH environment? How effective are house meetings in terms of resolving problems and conflicts? Internal consistency of items was strong (alpha=.98). Construct validity was supported by correlations with scores on the Community Oriented Program Evaluation Scale (Moos, Citation1997).

Analysis plan

Cronbach’s alpha was used to examine internal consistencies of the subscales. Correlations were used to assess relationships between LOS and recovery capital items. For each question on the RHAS we computed a one-way random effects, absolute agreement, single-measure ICC to test inter-rater reliability (Cicchetti, Citation1994). Factor analysis was conducted to look at the factor structure of the RHAS. The significance level for the factor loading followed Kline’s (Citation2000) recommendation for setting the criterion at a coefficient of >0.40.

Our primary outcome measure, days in the sober living home at the 6-month interview (LOS), was assessed using regression models adjusted for baseline sample characteristics. Separate models were conducted in Stata, Version 16.0 for the overall RHAS and each of the six subscales. We ran adjusted main effects models and explored potential interactions.

Based on previous studies (e.g., Mahoney et al., Citation2021), we expected the RHES would be associated with LOS. We also anticipated that it would interact with (i.e., moderate) the relationship between RHAS measures and days in the SLH. The formal test of the moderating effect of the RHES as used in our models can be shown as: LOS = α + β1(RHAS) + β2 (RHES) + β3 (RHAS*RHES) + Βx(baseline covariates) + ε. Because of the natural clustering of residents within the sober living houses studied, we accounted for resident clustering within SLHs using the vce(cluster [cluster variable]) option in Stata, which adjusts the standard errors of the estimators but not the estimated coefficients.

Results

Descriptive data

shows the mean scores for the overall RHAS, each of the RHAS subscales, as well as the average score for each question. Overall, the scores indicate good architectural characteristics across all subscales. The Shapiro–Wilk Test for normality was significant for all subscales, except for identity, indicating a lack of normalcy of the distribution (positive skew. The mean LOS was 188.2 days (SD = 127.9).

Table 1. RHAS means (SD)(N = 41), reliability coefficients, and 95% confidence intervals for subscales and overall RHAS (n = 32).

Psychometrics of the RHAS

Internal consistency

To assess the reliability of the RHAS, we first examined internal consistency of the subscales using Cronbach’s alpha. We found that alphas for each of the subscales were at acceptable levels, ranging from 0.88 to 0.97. The alpha for the overall scale that included all 25 items was 0.95.

Interrater reliability

As shown in , we found ICCs (1) ranging from 0.80 to 0.95 for the 25 items, .0.88 to 0.95 for the subscales, and .0.93 for the overall scale’s inter-rater reliability. According to Cicchetti (Citation1994), these ICCs range from good to excellent, showing a high level of agreement among raters and indicating that the RHAS was rated similarly across the 25 items.

Construct validity

A single item from the Recovery Capital Scale developed by White (Citation2009) was used to assess construct validity: “I live in a place free of alcohol and drugs” (see ). All subscales except Outdoor Common Areas correlated with the item. However, coefficients were modest, ranging from 0.100 (p<.05) for Sociability to 0.175 (p<.001) for Maintenance. We did explore other items to test for validity, but their correlations with RHAS subscales were inconsistent. These included variables assessing access to healthcare, spirituality, self-esteem, employment, and others.

Table 2. RHAS construct validity: Correlations between RHAS and SLH abstinence.

Factor structure

After performing principal component analysis of the six RHAS subscales, 73% of the variation could be accounted for by the first factor. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was used to test the null hypothesis that the original correlation matrix was an identity matrix. The test was significant (χ2= 197.38, P < 0.001), with Kaiser–Mayer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy at 0.86, both indicating the appropriateness of factor analysis. The analysis extracted one factor (). Because item communalities for the subscales ranged from 0.50 to 0.86, which was outside the 0.40 cutoff value, we moved forward using the RHAS and its subscales to test how architecture related to LOS.

Table 3. Loading of RHAS Subscales on a Single Factor.

Regression models

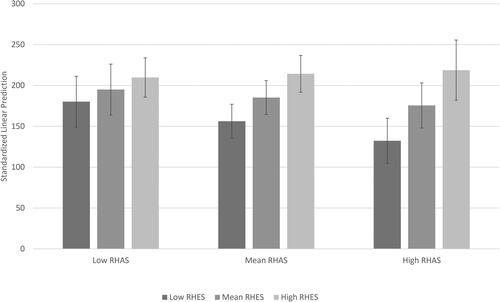

displays the results of our clustered regression models. As noted earlier, we followed a two-step process to understand independent effects of RHES and RHAS (overall and subscale scores) as well as their interactive effects on LOS. Regression models adjusted for intragroup correlations within the SLHs and for baseline covariates of race, age, sex, ASI alcohol (logged), ASI drug (logged), and ADCQ perceived costs of abstinence subscale scores. In models without the interaction term, RHES had a positive and significant (p < 0.05) relationship with LOS, however, none of the RHAS measures were independently associated with longer stays. Interaction effects (RHAS X RHES) were significant for three RHAS subscales as well as the overall RHAS: sociability (coef. = 2.53, se = 1.18, p = 0.001), quality of furnishings and fixtures (coef. = 1.62, se = 0.78, p = 0.044), personal and residence identity (coef. = 2.56, se = 0.70, p = 0.038) and RHAS total (coef. = 0.43, se = 0.19, p = 0.029). For interpretation, this indicates that for each unit increase in the RHES, the strength of the relationship between RHAS and SLH days increases by the value of the interaction coefficient (e.g., 0.43 for the RHAS total, as indicated in .). The intraclass correlation coefficient, the proportion of variance in LOS between SLHs, was small (0.09) and suggests the largest proportion of variance was across individuals (not tabled). For sensitivity, OLS regressions, fixed-effects (within), between-effects (between), and random-effects regressions were estimated; the results were consistent with findings from clustered models.

Table 4. Interaction of RHAS and RHES on days in the study site SLH.

To depict the interaction between RHES and the overall RHAS score, we grouped values for both measures at the mean and one standard deviation above and below the mean (Whisman & McClelland, Citation2005). As shown in , we labeled these “low,” “medium” and “high,” and used Stata’s post-estimation margins routines to obtain standardized predictive margins for LOS, evaluated at our fixed values of the RHAS and RHES while averaging over the remaining covariates. From , we see a pattern wherein high RHES displayed similar effects on LOS at all three RHAS levels as indicated by marginal predictions and 95% confidence intervals for the three grey bars: 209.8 (CI = 185.8–233.8), 214.3 (CI =191.7–236.8), and 286.8 (CI= 181.9–255.6). More to the point, increasing levels of RHES indicted differential effects at the mean level of RHAS, as shown by the three bars: 156.2 (CI = 135.5–177.0), 185.3 (CI = 169.6–200.9) and 214.3 (CI = 191.7–236.8) and the high level of RHAS (as shown by the three grey bars; 132.3 (CI = 104.7–159.9), 175.5 (CI = 151.2–199.8) and 218.8 (181.9–255.6). Marginal predictions and 95% confidence intervals at the low levels of RHAS were 180.2 (CI = 149.0–211.4), 194.9 (CI = 173.3–216.7) and 209.8 (CI = 185.8–233.8). Non-overlapping confidence intervals indicate statistical significance.

Discussion

Psychometric analyses of the RHAS showed good evidence of inter-rater reliability, internal consistency, and factor structure, as well as preliminary construct validity. Contrary to our hypotheses, study findings showed the six subscales of the RHAS as well as the total RHAS were not associated with LOS. We expected to find longer stays associated with better architecture for two reasons. First, we suspected better architecture would be associated with better health, safety, and esthetic characteristics, all of which would result in more favorable experiences living in the houses and, therefore, longer LOS. Second, we drew on descriptive and anecdotal reports on architecture in recovery homes (e.g., Wittman et al., Citation2014) to hypothesize that better architecture and efficient use of architecture to support recovery would improve the recovery environment and thereby motivate residents to remain in the houses.

House sample limitations

The finding that better architecture was not associated with LOS requires more research. However, there may be a variety of methodological limitations that influenced the lack of architecture effects. One issue is the characteristics of the sample of houses recruited. All houses in the study were members of the Sober Living Network in California and subject to standards and physical inspection of the premises. Thus, there is a high degree of homogeneity among the houses studied and that was reflected in consistently high RHAS scores across the houses. RHAS data were not normally distributed and that was born out in the Shapiro–Wilk Test for normality, which showed a positive skew. While we wanted consistency in the house sample and some assurance of quality control, the lack of variability in architecture may have made it difficult to identify strong support for construct validity and detect differences in outcomes (predictive validity). In future studies, it will be important to study the RHAS using more diverse samples and a wider variety of measures to assess construct and predictive validity (e.g., substance use and recovery capital).

One way to think about the potential role of architecture within the current study is that it may have provided the necessary physical characteristics for the social environment (i.e., the RHES) to flourish. Houses with very poor architectural characteristic were not included in the current study, and there are questions about whether social model activities could thrive under such conditions. Additional research will need to specify if there is an architectural threshold that is necessary for the implementation of social model recovery.

Social model effects

Consistent with previous studies (e.g., Polcin et al., Citation2021a), a measure of the frequency of social model interactions in the home, the RHES, was associated with LOS. The scale was designed to assess characteristics and activities consistent with social model recovery, which is the primary recovery model used by SLH providers. Overall, the findings suggest that what transpires between residents in the home, particularly in terms of supporting social model recovery principles, is more influential than the physical context where interactions take place.

Interaction effects

The absence of an effect for the RHAS on LOS combined with confirmation of our hypothesis that the RHES would predict LOS led us to consider how the effect of RHES might vary by RHAS. Our hypothesis that an interaction would be found where higher scores on RHES combined with higher scores on the RHAS would be associated with the longest LOS was not confirmed. shows that high RHES predicted the longest LOS in all three RHAS categories. In addition, the LOS for the high RHES category was nearly the same across the three RHAS levels. In contrast, low RHES consistently predicted the shortest lengths of stay in all three categories. In addition, there were notable differences in how low RHES was associated with LOS across the three RHAS categories. shows that in high RHAS houses, low RHES was especially problematic.

Reasons for this counterproductive interaction are unclear and require additional studies. It might be productive to use qualitative methods to understand the experiences of residents in high RHAS, low RHES houses that lead to briefer LOS. One potential line of inquiry might examine whether residents feel priorities are misplaced if great attention is paid to the physical environment but the emphasis on establishing long term recovery is limited or undervalued.

Overall, the implications for SLH providers are that they need to pay attention to the quality of the social model environment in the houses, particularly in houses that reflect good architectural characteristics. Without adequate social model influences in high RHAS houses, there is a danger of short LOS, which in other studies is associated with long-term substance use (Polcin, Mahoney & Mericle, 2021).

Considerations for providers

One use of the RHAS could be to use it to assess the overall quality of the living environment rather than a predictor of outcome. In that scenario, the RHAS would not be used to guide modifications that would necessarily improve substance use outcome, but it could be used to monitor the setting in terms of health, safety, and possibly the overall quality of the living experience of residents. From this perspective, good architectural characteristics can be seen as setting the necessary context for social model recovery to flourish.

Importantly, this study suggests residents can make significant improvements in SLHs that are resilient across different levels of architecture, provided they are able to implement social model recovery principles reflected in the RHES. This could be particularly important for low-fee houses where there are fewer resources for maintenance and upgrades.

House manager mobilization of architecture

Wittman et al. (Citation2014) and Wittman et al. (Citation2017) made the case that for architecture to have an impact it needs to work in concert with house goals, operations, and oversight. Those analyses were not conducted as part of the current study, and they constitute important issues to examine as research on recovery homes moves forward. The roles of house managers and the extent to which they consider how to mobilize architecture in service of recovery may be particularly important. A previous study of SLH managers (Polcin et al., Citation2021a) showed there is wide variation in how house managers view their roles. Some appear to view their roles as primarily administrative and focused on tasks such as collecting rent, paying bills, recruiting new residents, arranging needed repairs, and enforcing house rules. Other managers consider building a social model environment in the home and helping residents succeed in recovery as equally important. Future research should examine the interface between house manager roles and activities and how they influence the effect of architecture.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

This article was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grant Number DA042938). The funding organization had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- Burton, L. (2015). Mental well-being and the influence of place. In The Routledge handbook of planning for health and well-being (pp. 184–195). Routledge.

- Chrysikou, E. (2019). Psychiatric institutions and the physical environment: Combining medical architecture methodologies and architectural morphology to increase our understanding. Journal of Healthcare Engineering, 2019, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/4076259

- Cicchetti, D. V. (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6(4), 284–290. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284

- Cunningham, J. A., Sobell, L. C., Gavin, D. R., Sobell, M. B., & Breslin, F. C. (1997). Assessing motivation for change: Preliminary development and evaluation of a scale measuring the costs and benefits of changing alcohol or drug use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 11(2), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.11.2.107

- Kline, P. (2000). A psychometric primer. Free Association Books.

- Mahoney, E., Witbrodt, J., Mericle, A. A., & Polcin, D. L. (2021). Resident and house manager perceptions of social environments in sober living houses: Associations with length of stay. Journal of Community Psychology, 49(7), 2959–2971. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22620

- McLellan, A. T., Kushner, H., Metzger, D., Peters, R., Smith, I., Grissom, G., Pettinati, H., & Argeriou, M. (1992). The fifth edition of the addiction severity index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 9(3), 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s

- Mericle, A. A., Karriker-Jaffe, K., Patterson, D., Mahoney, E., Cooperman, L., & Polcin, D. L. (2020). Recovery in context: Sober living houses and the ecology of recovery. Journal of Community Psychology, 48(8), 2589–2607. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22447

- Mericle, A. A., Patterson, D., Howell, J., Subbaraman, M. S., Faxio, A., & Karriker-Jaffe, K. J. (2022). Identifying the availability of recovery housing in the U.S.: The NSTARR project. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 230, 109188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109188

- Moos, R. H. (1997). Evaluating treatment environments: The quality of psychiatric and substance abuse programs (2nd ed.). Transaction.

- Polcin, D. L., Korcha, R. A., & Bond, J. C. (2015). Interaction of motivation and psychiatric symptoms on substance abuse outcomes in sober living houses. Substance Use & Misuse, 50(2), 195–204. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2014.962055

- Polcin, D. L., Korcha, R., Bond, J., & Galloway, G. (2010). What did we learn from our study on sober living houses and where do we go from here? Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 42(4), 425–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2010.10400705

- Polcin, D. L., Korcha, R., Witbrodt, J., Mericle, A. A., & Mahoney, E. (2018). Motivational Interviewing Case Management (MICM) for persons on probation or parole entering sober living houses. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 45(11), 1634–1659. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854818784099

- Polcin, D. L., Mahoney, E., & Mericle, A. A. (2021a). House manager roles in sober living houses. Journal of Substance Use, 26(2), 151–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2020.1789230

- Polcin, D. L., Mahoney, E., & Mericle, A. A. (2021b). Psychometric properties of the recovery home environment scale. Substance Use & Misuse, 56(8), 1161–1168. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2021.1910710

- Polcin, D. L., Mahoney, E., Witbrodt, J., & Mericle, A. A. (2020). Recovery home environment characteristics associated with recovery capital. Journal of Drug Issues, 51(2), 253–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022042620978393

- Polcin, D. L., Mericle, A., Howell, J., Sheridan, D., & Christensen, J. (2014). Maximizing social model principles in residential recovery settings. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 46(5), 436–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2014.960112

- Reif, S., George, P., Braude, L., Dougherty, R. H., Daniels, A. S., Ghose, S. S., & Delphin-Rittmon, M. E. (2014). Recovery housing: Assessing the evidence. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 65(3), 295–300. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300243

- Scheid, T. L. (2018). Tie a knot and hang on: Providing mental health care in a turbulent environment. Routledge.

- Shaw, FT., & Borkman, T. (Eds.). (1990). Social model alcohol recovery: An environmental approach. Bridge Focus.

- Timko, C. (1996). Physical characteristics of residential psychiatric and substance abuse programs: Organizational determinants and patient outcomes. American Journal of Community Psychology, 24(1), 173–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02511886

- Whisman, M. A., & McClelland, G. H. (2005). Designing, testing, and interpreting interactions and moderator effects in family research. Journal of Family Psychology: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 19(1), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.19.1.111

- White, W. (2009). Recovery capital scale. www.williamwhitepapers.com.

- Witbrodt, J., Polcin, D., Korcha, R., & Li, L. (2019). Beneficial effects of motivational interviewing case management: A latent class analysis of recovery capital among sober living residents with criminal justice involvement. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 200, 124–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.03.017

- Wittman, F. (1989). Housing models for alcohol programs serving homeless people. Contemporary Drug Problems, 16(3), 483–504.

- Wittman, F. (1993). Affordable housing for people with alcohol and other drug problems. Contemporary Drug Problems, 20(3), 541–609.

- Wittman, F., Jee, B., Polcin, D. L., & Henderson, D. (2014). The setting is the service: How the architecture of Sober living residences supports community-based recovery. International Journal of Self Help & Self Care, 8(2), 189–225. https://doi.org/10.2190/SH.8.2.d

- Wittman, F. D., & Polcin, D. L. (2014). The evolution of peer run sober housing as a recovery resource for California communities. International Journal of Self Help & Self Care, 8(2), 157–187. https://doi.org/10.2190/SH.8.2.c

- Wittman, F., Polcin, D., & Sheridan, D. (2017). The architecture of recovery: Two kinds of housing assistance for chronic homeless persons with substance use disorders. Drugs and Alcohol Today, 17(3), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1108/DAT-12-2016-0032