Abstract

Background: Research suggests flavor facilitates cigarillo use, but it is unknown if flavor impacts patterns of co-use of cigarillos and cannabis (“co-use”), which is common among young adult smokers. This study’s aim was to determine the role of the cigarillo flavor in co-use among young adults. Methods: Data were collected (2020-2021) in a cross-sectional online survey administered to young adults who smoked ≥2 cigarillos/week (N = 361), recruited from 15 urban areas in the United States. A structural equation model was used to assess the relationship between flavored cigarillo use and past 30-day cannabis use (flavored cigarillo perceived appeal and harm as parallel mediators), including several social-contextual covariates (e.g., flavor and cannabis policies). Results: Most participants reported usually using flavored cigarillos (81.8%) and cannabis use in the past 30 days (“co-use”) (64.1%). Flavored cigarillo use was not directly associated with co-use (p = 0.90). Perceived cigarillo harm (β = 0.18, 95% CI = 0.06, 0.29), number of tobacco users in the household (β = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.10, 0.33), and past 30-day use of other tobacco products (β = 0.23, 95% CI = 0.15, 0.32) were significantly positively associated with co-use. Living in an area with a ban on flavored cigarillos was significantly negatively associated with co-use (β = -0.12, 95% CI = -0.21, −0.02). Conclusions: Use of flavored cigarillos was not associated with co-use; however, exposure to a flavored cigarillo ban was negatively associated with co-use. Cigar product flavor bans may reduce co-use among young adults or have a neutral impact. Further research is needed to explore the interaction between tobacco and cannabis policy and use of these products.

Introduction

Although the prevalence of cigarette smoking has declined among young adults (YAs) over time, prevalence of YA cigar smoking has remained relatively consistent over time in the United States (US) (Agaku et al., Citation2014; Cornelius et al., Citation2022). About 4% of YAs reported smoking cigars every day or some days in 2020 (Cornelius et al., Citation2022), a 20% increase since 2012 (Agaku et al., Citation2014). In the US, little cigars and cigarillos (unfiltered cigars about 3-4 inches long typically containing three grams of tobacco) (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, Citation2022) are disproportionately used by males, Black non-Hispanics, and those with low income and less education (Phan et al., Citation2021). YAs are twice as likely as older adults to use cigarillos (Phan et al., Citation2021).

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has proposed a product standard to ban all non-tobacco flavors in cigars (including the cigar wrapper), including menthol (U.S. Food & Drug Administration, Citation2021). In the US, the vast majority (73%) of YA any tobacco users and half of YA cigar smokers use a flavored product (Rostron et al., Citation2020; Villanti et al., Citation2017), so this regulation could significantly reduce tobacco use in this population and benefit public health. As the tobacco and nicotine product landscape continues to evolve, new tobacco control policies need to account not only for the possible effect on tobacco use, but also on use of other substances. Cannabis is frequently co-used with tobacco (co-administered in a blunt [removing tobacco from cigar wrapper and replacing with cannabis] or sequentially used) (Cohn & Chen, Citation2022), so it should be observed as tobacco control policies are passed. This study (along with a previous analysis from the same study (Glasser et al., Citation2022)) is the first to directly assess the role that cigar flavor, a potential regulatory target, plays in patterns of co-use of tobacco and cannabis, an increasingly prevalent behavior (Schauer & Peters, Citation2018).

While tobacco use has declined over time, the prevalence of cannabis use has increased in the US (Mauro et al., Citation2018), and is highest among YAs (National Academy of Sciences Engineering and Medicine (NASEM), Citation2017). Almost half of YA tobacco users in the US co-use tobacco and cannabis (Cohn & Chen, Citation2022). Using cannabis and tobacco together may expose smokers to higher levels of toxicants than those who only use one product (Meier & Hatsukami, Citation2016). In addition, co-using is associated with greater frequency of use of and dependence on both tobacco and cannabis (Albert et al., Citation2020; Montgomery, Citation2015) and can hamper one’s ability to quit both substances (Agrawal et al., Citation2012; Driezen et al., Citation2022; Lemyre et al., Citation2019). Disparities in co-use mirror disparities in cigarillo smoking, with use concentrated among low income, less educated, and racial/ethnic minority smokers (Mantey et al., Citation2021; Pulvers et al., Citation2018; Seaman, Green, et al., Citation2019). Co-users are also more likely to engage in poly-tobacco use, experience symptoms of depression or anxiety, and be exposed to peer/family smoking and tobacco advertising (Lipperman-Kreda et al., Citation2022; Mantey et al., Citation2021; Pulvers et al., Citation2018; Seaman, Green, et al., Citation2019; Seaman, Howard, et al., Citation2019). Research is mixed on whether cannabis and tobacco are substitutes or complements (Agrawal et al., Citation2012; Lemyre et al., Citation2019; Peters et al., Citation2017), and evidence suggests that use of one product is associated with increased risk of using the other (Cornacchione Ross et al., Citation2020; Fairman & Anthony, Citation2018; Mayer et al., Citation2020).

The most commonly used tobacco product among co-users of tobacco and cannabis is cigars, particularly cigarillos (Cohn & Chen, Citation2022). In the US, three-quarters of cannabis users and two-thirds of blunt users smoke cigars (Audrain-McGovern et al., Citation2019; Seaman et al., Citation2020). About 40%-60% of cigarillo users modify them for blunt use (Kong et al., Citation2017; Trapl et al., Citation2016). About 86% of adolescent co-users report concurrent cigar and blunt use (Schauer & Peters, Citation2018). Qualitative research suggests that flavor is a highly valued characteristic of cigarillos to mask the smell of cannabis (Antognoli et al., Citation2018; Giovenco et al., Citation2016; Kong et al., Citation2018) or enhance the smoking experience (Kong et al., Citation2018). One study has reported that 83% of adult blunt users used a flavored cigar wrapper (Rosenberry et al., Citation2017). Focus groups reveal that cigarillos are preferred for blunts because they are cheap and easy to access (Kong et al., Citation2018).

Flavors in cigar products may influence co-use patterns through altering perceptions of harm and appeal. Flavored cigar products are perceived as less harmful than unflavored products, which is associated with increased risk of use of cigars (Nyman et al., Citation2018; Sterling et al., Citation2016; Sterling et al., Citation2019). In addition, flavored products are viewed as more appealing than unflavored products (Huang et al., Citation2017), and greater perceived appeal is associated with susceptibility to flavored cigar use (Chaffee et al., Citation2017). Although evidence indicates cigar flavor facilitates use through these mechanisms (increasing appeal and reducing harm), no studies have determined whether they operate similarly for the role of flavor in co-use of cigars and cannabis. While studies are increasingly examining the effect of cannabis policy on tobacco use (Coley et al., Citation2021; Schlienz & Lee, Citation2018; Vuolo et al., Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2016; Weinberger et al., Citation2022), there is little evidence of the impact of tobacco control measures (e.g., banning flavors) related directly to cigars on cannabis use.

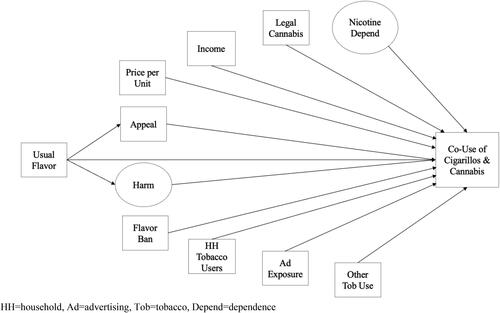

Research shows that availability of flavors facilitates use through increased appeal and reduced perceived harm of cigarillos (Nyman et al., Citation2018; Setodji et al., Citation2018; Sterling et al., Citation2016; Sterling et al., Citation2019), but it is unknown whether using a flavored cigarillo similarly promotes the co-use of cigarillos and cannabis. In this exploratory study, we sought to determine the role of cigarillo flavor in use of cigarillos and cannabis in the past 30 days (“co-use”) among YAs to inform tobacco regulation related to flavors. We focus on YAs since a greater proportion of YAs co-use compared with youth and older adults (Cohn & Chen, Citation2022; Smith et al., Citation2021). We hypothesized that YAs who use flavored cigarillos will be more likely to co-use cannabis or blunts than those using unflavored cigarillos, indirectly through increased product appeal and decreased perceptions of harm.

Materials and methods

We conducted a secondary analysis of data from a non-probability convenience sample of participants in the Cigarillos Flavor and Abuse Liability, Attention, and Substitution (C-FLASH) Study, designed to evaluate perceptions of flavors on appeal, purchasing and risk perceptions of cigarillo products among YA cigarillo users. YA cigarillo users were recruited (N = 361), and data were collected in a cross-sectional survey conducted in 2020-2021. We obtained informed consent from all participants prior to inclusion in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Case Western Reserve University (#STUDY20191769).

Study procedures

C-FLASH Study participants were recruited via social media advertisements targeted to 15 geographic regions in the US (Supplemental Table 1) with known high youth cigar use prevalence (Kann et al., Citation2018). A brief, web-based screening survey was used to determine eligibility. Participants who screened eligible, provided their email address, and passed several checks for fraudulent responses (e.g., non-duplicate IP address) (Heffner et al., Citation2021) were sent an email inviting them to provide informed consent and complete a secured online survey. Participants were eligible if they were 1) currently 21-28 years old; 2) smoked an average of at least two cigarillos per week over the past month; and 3) willing to provide informed consent and participate in the online survey. Participants who successfully completed the survey via unique survey link received a $15 electronic gift card.

Table 1. Demographics and other characteristics of young adults who used cigarillos in the past 30 days (N = 361).

Study measures

Dependent variable

The dependent variable was past 30-day cannabis (“marijuana, cannabis, hash, THC, grass, pot, or weed”) use (as all participants were cigarillo users, this amounts to co-use). For sensitivity analyses, we examined blunt use specifically (“How do you usually use your marijuana, cannabis, hash, THC, grass, pot, or weed? [I smoke it as a blunt; I smoke it as a joint or in a pipe or bong; I vape it in an e-cigarette or vape pen; I eat it, drink it, or ingest it in some way; I use it some other way]”), dropping cannabis users who reported usually using cannabis other ways than through a blunt.

Independent variables

The independent variable of interest was usual flavored cigarillo use (“When you use cigarillos do you usually use flavors like fruit, sweet and candy, mint, alcohol, menthol or other flavor?”). We examined individual, peer, and environmental covariates to account for potential influences on co-use behavior as supported by empirical data and theorized by the Social Contextual Model of Health Behavior (Sorensen et al., Citation2003). These included annual income, past 30-day use of other tobacco products (cigarettes/e-cigarettes/hookah/smokeless), nicotine dependence (scale of 12 proposed items (Flocke et al., Citation2022); Supplemental Table 2 [higher score indicates greater dependence]), number of people in the household who use any tobacco or nicotine products, amount usually spent per unit for cigarillos (money typically spent divided by amount typically purchased), past 6-month frequency of exposure to tobacco advertising, living in a zip code with a ban on flavored cigarillos (Public Health Law Center, Citation2021; Truth Initiative, Citation2021), and living in a state with legalized recreational cannabis (https://disa.com/map-of-marijuana-legality-by-state).

Table 2. Structural equation model fit statistics and standardized path estimates across competing models.

Mediators and effect measure modifiers

Perceived appeal of flavored cigarillos and cigarillo harm were hypothesized parallel mediators of the relationship between flavor use and co-use. Appeal was measured using a 7-point Likert scale indicating agreement with, “flavored cigarillos are appealing”. Harm was assessed with a scale of 10 proposed items (Supplemental Table 2; higher scores indicate greater perceived harm). Gender identity (male vs. female) and race/ethnicity (racial/ethnic minority vs. White non-Hispanic) were examined in effect measure modification analysis and measurement invariance testing (Cohn et al., Citation2016; Nyman et al., Citation2018; Odani et al., Citation2020; Schauer & Peters, Citation2018; Seaman, Green, et al., Citation2019).

Data analysis

We calculated frequencies or means and standard deviations for descriptive statistics. To compare usual flavored cigarillo users (vs. unflavored users) and cannabis users (vs. non-users) we ran Pearson’s Chi-square Test for Independence or Fisher’s Exact Test (for those with cell sizes ≤5) (Kim, Citation2017) for categorical variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables. For non-normally distributed continuous variables (amount spent per cigarillo unit purchased and perceived harm), we calculated median and interquartile range and conducted a two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann–Whitney) test for group differences.

We conducted a structural equation model (SEM; details of which can be found elsewhere (Glasser et al., Citation2022)) to test the study hypothesis that flavored cigarillo users will be more likely to co-use cannabis (vs. unflavored cigarillo users) through increased product appeal and decreased perceived harm. SEM was preferred for this analysis because it allowed us to reliably test hypothetical relationships among many observed and latent theoretical constructs simultaneously (Deng et al., Citation2018). In brief, we first conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess measurement of nicotine dependence as a covariate and cigarillo harm perceptions as a mediator using data from the full sample. We then ran the full SEM in Mplus 8 after preparing data in Stata SE 17 and handling missing data in Blimp Studio 1.3.5. Missing data ranged from 0-16% across variables of interest (9% and 6% for primary predictor and outcome, respectively), and data were missing at random. We employed latent fully conditional specification imputation methods to impute missing data (five imputed datasets) (Lee & Carlin, Citation2010) for SEM analyses. As we included variables measured on an ordinal scale in our analyses, we used weighted least square mean and variance adjusted estimation. We determined that the proposed measurement and structural models of the SEM had power >0.80 (MacCallum et al., Citation1996).

Model selection

After we finalized the measurement model based on fit (χ2 non-significant p value at p < 0.05 (West et al., Citation2012), Comparative Fit Index [CFI] and Tucker Lewis Index [TLI] ≥ 0.95 (West et al., Citation2012), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation [RMSEA] estimate ≤0.06 and upper 90% confidence limit ≤0.06 (MacCallum et al., Citation1996), and standardized root mean squared residual [SRMR] ≤ 0.08 (West et al., Citation2012)), we conducted invariance testing (Bowen & Masa, Citation2015) and removed items with non-significant standardized factor loadings of <0.40 or coefficients of determination (R2) of <0.50 (indicative of poor indicator of the latent construct) (Stevens, Citation1992). In the structural model, we removed non-significant correlations from the model if doing so did not conflict with the theory underpinning this analysis. Alternative models were compared: indirect effects from usual flavored cigarillo use to co-use through perceived harm and appeal (originally hypothesized model; Model 1), indirect effects through only one pathway (harm or appeal) (Models 2 & 3), and no indirect effects (Model 4).

Results

Participant characteristics

Participants (N = 361) were on average 24.7 years of age, and the majority identified as male (57.6%) and reported income of <$25,000 per year (57.3%) (). About one-third each identified as Black non-Hispanic or White non-Hispanic. Most reported using other tobacco products in the past 30 days (80.8%), usually using flavored cigarillos (81.8%), and not living in an area with legalized recreational cannabis (72.2%) or a flavored cigarillo ban (86.7%). The majority also used cannabis in the past 30 days (64.1%); 66.5% of cannabis users usually smoked blunts. Geographically, participants represented 46 US states and the District of Columbia.

Compared to participants who do not usually smoke flavored cigarillos, those who do reported higher nicotine dependence, reported seeing smoking advertisements frequently, agreed that flavored cigarillos are appealing, perceived lower cigarillo harm, and more frequently lived in an area with a flavored cigarillo ban (). A greater proportion of past 30-day cannabis users used other tobacco products and lived with more smokers than cannabis non-users. The average price paid for a cigarillo was lower and median perceived cigarillo harm was greater for cannabis users than non-users, and cannabis users were less likely to report noticing smoking advertising and to live in an area with a flavored cigarillo ban.

Measurement model

Results of the CFA (published elsewhere with consistent results among a sub-sample of participants) (Glasser et al., Citation2022) indicate a two-factor measurement model with seven indicators of harm perceptions and eight indicators of nicotine dependence (Supplemental Table 3). The final model, invariant across gender identity and race/ethnicity, explained 63.4% and 55.4% of the variance in harm and dependence, respectively.

General SEM

Usual flavored cigarillo use

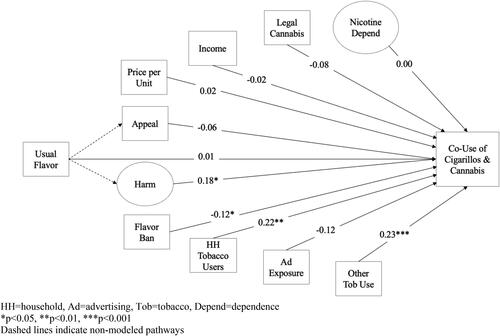

The originally hypothesized model is depicted in . We determined that there was no multicollinearity in the model (all Variance Inflation Factor scores were <1.4) (Johnston et al., Citation2018). In this model, there was a significant indirect effect of usual flavored cigarillo use on co-use of cannabis through perceived harm (, Model 1). Using a flavored cigarillo was negatively associated with perceived harm (β = –0.22, 95% CI = –0.33, −0.12), and perceived harm was positively associated with using cannabis in the past 30 days (β = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.10, 0.34). So, using a flavored cigarillo was associated with a reduced likelihood of cannabis co-use indirectly through reduced perceptions of cigarillo harm (β = –0.05, 95% CI = –0.08, −0.02). However, this model did not meet all a priori fit criteria (χ2 p value across all datasets was significant at p < 0.05; Supplemental Table 4). Modifying the model to specify only one indirect effect (harm or appeal, Models 2 and 3) each had better fit, but modeling only a direct effect (Model 4) resulted in the best model fit (West et al., Citation2012). In this model, controlling for covariates, usual use of a flavored cigarillo was not significantly associated with past 30-day cannabis co-use. About 20% (p < 0.01) of the variance in cannabis use was explained by this model.

Covariates

Standardized estimates for Model 4 are shown in . As in the original model, in Model 4, perceived harm of cigarillos was positively associated with co-use (β = 0.18, 95% CI = 0.06, 0.29). In addition, the number of tobacco users in the household (β = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.10, 0.33) and use of other tobacco products in the past 30 days (β = 0.23, 95% CI = 0.15, 0.32) were significantly positively associated with co-use. Living in an area with a ban on flavored cigarillos was significantly negatively associated with co-use (β = –0.12, 95% CI = –0.21, −0.02). No other covariates were associated with co-use.

We conducted multiple-group testing by gender identity and race/ethnicity with Model 4, as it was the best-fitting model. All pathways and variances were not significantly different across categories, so Model 4 was invariant across gender and race/ethnicity.

Sensitivity analyses

We ran all models again restricting the outcome to blunt use specifically (vs. no cannabis use) (Supplemental Table 5). Results were consistent with models including all cannabis users, but the proportion of the variance in blunt use explained by the model was slightly higher (R2 = 0.31, p < 0.001). In addition, living in an area with a flavor ban was not a significant predictor of blunt use.

Discussion

This study directly assessed the role that cigarillo flavor plays in patterns of co-use of cigarillos and cannabis among a sample of YAs. About 80% of YA cigarillo users in this sample usually smoked a flavored cigarillo, which is higher than among US YAs nationally (51.4% of every day or someday cigarillo users in 2016/2017) (Rostron et al., Citation2020). Sixty-four percent of these YAs used cannabis, which is slightly higher than the 48% of YA tobacco users who report past 30-day cannabis use (Cohn et al., Citation2021).

There was no direct effect of usual flavored cigarillo use on co-use with cannabis. Previous analyses of young adults from the C-FLASH Study examined cigarillo flavor and motivation to quit among co-users and similarly found no association (Glasser et al., Citation2022). Given that most cigarillo smokers used flavored products and that other studies suggest that using flavored cigar wrappers for blunts is common (Rosenberry et al., Citation2017), flavor may not be a factor of concern when deciding to co-use (i.e., is more of a default). Contrary to our hypotheses, flavored cigarillo use was also not indirectly associated with co-use of cigarillos and cannabis (including among blunt users) through increased appeal of flavored cigarillos. Although usual flavored cigarillo use and perceived appeal of flavored cigarillos were positively associated, as expected (Sterling et al., Citation2015), there was no relationship between appeal and co-use with cannabis. Despite the appeal of flavored cigarillos, there could be another unmeasured mechanism, such as the flavor’s utility in masking the smell of cannabis or enhancing the high (Antognoli et al., Citation2018; Giovenco et al., Citation2016; Kong et al., Citation2018), by which flavor could facilitate cannabis use. Or perhaps flavor has no bearing on whether YAs co-use. Future studies should explore the importance of flavor in co-use with cannabis further and potential behavior change if flavors were to be banned through a product standard in the US or in other countries or jurisdictions, as well as the role of other cigarillo product characteristics on co-use with cannabis. Research may also be needed to explore if frequency or quantity of cigarillo use, in relation to product characteristics or other factors, may be associated with frequency/quantity of cannabis use. Exploration is also needed in countries with different policy environments (e.g., in Canada where flavored cigars are banned and cannabis is legalized) (Erinoso et al., Citation2021).

Findings in this study were partly consistent with our hypothesis that usual use of a flavored cigarillo was indirectly associated with cannabis co-use through perceived cigarillo harm, although this result came from a model with non-optimal fit statistics. We predicted flavored use would be positively associated with co-use, but we found a negative association. The finding that usual use of a flavored cigarillo was associated with reduced perceptions of cigarillo harm is supported by evidence from other studies (Feirman et al., Citation2016). That co-use was more likely for those who perceived greater cigarillo harm was unexpected; however, studies show that cannabis use can be viewed as less harmful than cigar smoking; blunt use in particular is seen as less harmful than using cigars with tobacco (Sterling et al., Citation2016; Trapl & Koopman Gonzalez, Citation2018). Therefore, co-users in this study may have been more likely to use cannabis because they believed cigarillos containing tobacco were more harmful (relative harm was not assessed in our study) and wanted to reduce their tobacco use. Future research should explore motivations to co-use related to relative risk perceptions. Additional research may also be needed to establish valid tobacco and cannabis risk perception scales and determine if there is differential perceived risk across tobacco flavor types.

Living in an area with a cigarillo flavor ban was negatively related to co-use (not observed among blunt users). This result could indicate that banning the sale of flavored cigar products could reduce cannabis use among cigarillo users; however, these data are cross-sectional, so it is possible that young adults who may have stopped using cigarillos as a result of a flavor ban are therefore not included in this sample and could be consuming cannabis another way. Most cigarillos are flavored, so a flavor ban may also result in reduced overall availability of cigarillos and blunt wraps, which was found in an analysis of flavor bans in California (Timberlake et al., Citation2021). Interestingly, in our study, a higher proportion of flavored cigarillo smokers lived in areas with a cigarillo flavor ban than unflavored smokers. It is possible that policies are passed in areas where they would be most needed (e.g., a higher proportion of flavored smokers live there), the strength and enforcement of flavor bans varies (Rose et al., Citation2020), or tobacco companies have circumvented these policies by continuing to sell “concept” flavors with non-descript names, like “Jazz,” that do not explicitly refer to flavors. Some flavor bans have been evaluated and resulted in reduced sale of flavored cigars, but increased sale of concept flavors, which can undermine success of these policies (Kephart et al., Citation2020; Rogers et al., Citation2019).

Living with more tobacco users was a significant predictor of co-use in our model. Research has shown the influence of descriptive norms (normal behavior perceived/observed) of smoking among family members and peers within the household on tobacco smoking behavior (East et al., Citation2021), and one national study of US YAs found that co-users of cigarettes and cannabis were more likely to live with a smoker than cannabis-only users (Seaman, Green, et al., Citation2019). Another significant predictor of co-use in our study was use of tobacco products other than cigarillos. This finding is consistent with several other studies that have shown co-use is associated with poly-tobacco product use (Cho et al., Citation2021; Cobb et al., Citation2018; Seaman, Howard, et al., Citation2019). Efforts targeting co-use behaviors may need to consider the full spectrum of products used and the exposure to use in one’s social environment.

Limitations

Although statistically significant, the proportion of variance explained by the model we ran in this exploratory study was about 20%. Other factors, not measured in this study, may be driving co-use, such as mental health or cannabis use severity. More exploration of these factors is needed and in different samples of YAs. In addition, given the lack of evidence on the relationship between cigarillo flavor and co-use, there are other theoretically viable relationships (e.g., perceived harm and flavor appeal leading to flavor use, rather than the reverse, which could then impact co-use) that may require exploration. Given both a “gateway” and “reverse gateway” hypothesis are supported by current evidence (Lemyre et al., Citation2019), examining whether cannabis use could be a predictor of flavored cigarillo use is also worth investigation.

In what manner participants co-used cannabis with cigarillos (i.e., sequentially using, co-administering) in the past 30 days was not measured, and we did not explore differences by preferred flavor type used, both of which could reveal heterogeneity of effects (Chen-Sankey et al., Citation2019). Users of concept flavors may not have perceived their product as flavored, so misclassification of flavored cigarillo use is possible. The non-probability sample targeted recruitment of cigarillo users, so our findings may not be able to be generalized to individuals who use other combinations of tobacco and cannabis or YAs in other settings or periods of time (data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic). The fact that a larger proportion of cigarillo users in this sample used flavored products than in the general population of young adults may have introduced selection bias and resulting small cell sizes may reduce the precision of the estimates. We cannot infer causal relationships from this model as data were cross-sectional, but SEM methodology allowed us to examine multiple relevant pathways, indirect effects, and valid measurement of two key variables.

Conclusions

Restricting the sale of flavored cigars has great potential to reduce prevalence of cigar smoking and has begun to show positive public health impact at the local level in the US (Rose et al., Citation2020) and other places globally (Chaiton et al., Citation2019). However, unintended consequences need to be monitored, including the impact on cannabis use. Based on our finding that those living in an area with a flavored cigarillo ban were less likely to co-use, coupled with finding no significant relationship between using a flavored cigarillo and co-use outcomes in both this analysis and our previous analysis from the same study (Glasser et al., Citation2022), a possible product standard to ban flavors in cigar products may have a positive or neutral impact on co-use with cannabis among YAs. Further research is needed to explore the interaction between tobacco and cannabis policy and use of these products.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (32.5 KB)Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank non-author members of AG’s PhD dissertation committee (Micah Berman and Darren Mays) for their guidance in supporting this project. We would also like to thank Natasha Bowen for her guidance in structural equation modeling.

Declaration of interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agaku, I. T., King, B. A., Husten, C. G., Bunnell, R., Ambrose, B. K., Hu, S. S., Holder-Hayes, E., & Day, H. R. (2014). Tobacco product use among adults–United States, 2012-2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 63(25), 542–547. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24964880

- Agrawal, A., Budney, A. J., & Lynskey, M. T. (2012). The co-occurring use and misuse of cannabis and tobacco: A review. Addiction, 107(7), 1221–1233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03837.x

- Albert, E. L., Ishler, K. J., Perovsek, R., Trapl, E. S., & Flocke, S. A. (2020). Tobacco and marijuana co-use behaviors among cigarillo users. Tobacco Regulatory Science, 6(5), 306–317. https://doi.org/10.18001/TRS.6.5.1

- Antognoli, E., Koopman Gonzalez, S., Trapl, E., Cavallo, D., Lim, R., Lavanty, B., & Flocke, S. (2018). The social context of adolescent co-use of cigarillos and marijuana blunts. Substance Use & Misuse, 53(4), 654–661. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2017.1355388

- Audrain-McGovern, J., Rodriguez, D., Alexander, E., Pianin, S., & Sterling, K. L. (2019). Association between adolescent blunt use and the uptake of cigars. JAMA Network Open, 2(12), e1917001. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.17001

- Bowen, N. K., & Masa, R. D. (2015). Conducting measurement invariance tests with ordinal data: A guide for social work researchers. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 6(2), 229–249. https://doi.org/10.1086/681607

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Smoking & tobacco use: Cigars. Retrieved June 2, from https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/tobacco_industry/cigars/index.htm

- Chaffee, B. W., Urata, J., Couch, E. T., & Gansky, S. A. (2017). Perceived flavored smokeless tobacco ease-of-use and youth susceptibility. Tobacco Regulatory Science, 3(3), 367–373. https://doi.org/10.18001/TRS.3.3.12

- Chaiton, M. O., Schwartz, R., Tremblay, G., & Nugent, R. (2019). Association of flavoured cigar regulations with wholesale tobacco volumes in Canada: an interrupted time series analysis. Tobacco Control, 28(4), 457–461. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054255

- Chen-Sankey, J. C., Choi, K., Kirchner, T. R., Feldman, R. H., Butler, J., 3rd., & Mead, E. L. (2019). Flavored cigar smoking among African American young adult dual users: An ecological momentary assessment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 196, 79–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.12.020

- Cho, J., Goldenson, N. I., Kirkpatrick, M. G., Barrington-Trimis, J. L., Pang, R. D., & Leventhal, A. M. (2021). Developmental patterns of tobacco product and cannabis use initiation in high school. Addiction, 116(2), 382–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15161

- Cobb, C. O., Soule, E. K., Rudy, A. K., Sutter, M. E., & Cohn, A. M. (2018). Patterns and correlates of tobacco and cannabis co-use by tobacco product type: Findings from the virginia youth survey. Substance Use & Misuse. 53(14), 2310–2319. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2018.1473437

- Cohn, A., Johnson, A., Ehlke, S., & Villanti, A. C. (2016). Characterizing substance use and mental health profiles of cigar, blunt, and non-blunt marijuana users from the National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 160, 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.017

- Cohn, A. M., Blount, B. C., & Hashibe, M. (2021). Nonmedical cannabis use: Patterns and correlates of use, exposure, and harm, and cancer risk. JNCI Monographs, 2021(58), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgab006

- Cohn, A. M., & Chen, S. (2022). Age groups differences in the prevalence and popularity of individual tobacco product use in young adult and adult marijuana and tobacco co-users and tobacco-only users: Findings from Wave 4 of the population assessment of tobacco and health study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 233, 109278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109278

- Coley, R. L., Kruzik, C., Ghiani, M., Carey, N., Hawkins, S. S., & Baum, C. F. (2021). Recreational marijuana legalization and adolescent use of marijuana, tobacco, and alcohol. Journal of Adolescent Health, 69(1), 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.10.019

- Cornacchione Ross, J., Sutfin, E. L., Suerken, C., Walker, S., Wolfson, M., & Reboussin, B. A. (2020). Longitudinal associations between marijuana and cigar use in young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 211, 107964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.107964

- Cornelius, M. E., Loretan, C. G., Wang, T. W., Jamal, A., & Homa, D. M. (2022). Tobacco product use among adults – United States, 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 71(11), 397–405. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7111a1

- Deng, L., Yang, M., & Marcoulides, K. M. (2018). Structural equation modeling with many variables: A systematic review of issues and developments. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 580. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00580

- Driezen, P., Gravely, S., Wadsworth, E., Smith, D. M., Loewen, R., Hammond, D., Li, L., Abramovici, H., McNeill, A., Borland, R., Cummings, K. M., Thompson, M. E., & Fong, G. T. (2022). Increasing cannabis use is associated with poorer cigarette smoking cessation outcomes: Findings from the ITC four country smoking and vaping surveys, 2016–2018. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 24(1), 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntab122

- East, K., McNeill, A., Thrasher, J. F., & Hitchman, S. C. (2021). Social norms as a predictor of smoking uptake among youth: A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of prospective cohort studies. Addiction, 116(11), 2953–2967. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15427

- Erinoso, O., Clegg Smith, K., Iacobelli, M., Saraf, S., Welding, K., & Cohen, J. E. (2021). Global review of tobacco product flavour policies. Tobacco Control, 30(4), 373–379. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055454

- Fairman, B. J., & Anthony, J. C. (2018). Does starting to smoke cigars trigger onset of cannabis blunt smoking? Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 20(3), 355–361. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntx015

- Feirman, S. P., Lock, D., Cohen, J. E., Holtgrave, D. R., & Li, T. (2016). Flavored tobacco products in the United States: A systematic review assessing use and attitudes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 18(5), 739–749. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntv176

- Flocke, S. A., Ishler, K., Albert, E., Cavallo, D., Lim, R., & Trapl, E. (2022). Measuring nicotine dependence among adolescent and young adult cigarillo users. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 24(11), 1789–1797. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntac117

- Giovenco, D. P., Miller Lo, E. J., Lewis, M. J., & Delnevo, C. D. (2016). “They’re pretty much made for blunts”: Product features that facilitate marijuana use among young adult cigarillo users in the United States. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 19(11), ntw182–1364. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntw182

- Glasser, A. M., Nemeth, J. M., Quisenberry, A. J., Shoben, A. B., Trapl, E. S., & Klein, E. G. (2022). Cigarillo flavor and motivation to quit among co-users of cigarillos and cannabis: A structural equation modeling approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5727. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095727

- Heffner, J. L., Watson, N. L., Dahne, J., Croghan, I., Kelly, M. M., McClure, J. B., Bars, M., Thrul, J., & Meier, E. (2021). Recognizing and preventing participant deception in online nicotine and tobacco research studies: Suggested tactics and a call to action. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 23(10), 1810–1812. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntab077

- Huang, L. L., Baker, H. M., Meernik, C., Ranney, L. M., Richardson, A., & Goldstein, A. O. (2017). Impact of non-menthol flavours in tobacco products on perceptions and use among youth, young adults and adults: A systematic review. Tobacco Control, 26(6), 709–719. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053196

- Johnston, R., Jones, K., & Manley, D. (2018). Confounding and collinearity in regression analysis: A cautionary tale and an alternative procedure, illustrated by studies of British voting behaviour. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1957–1976. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0584-6

- Kann, L., McManus, T., Harris, W. A., Shanklin, S. L., Flint, K. H., Queen, B., Lowry, R., Chyen, D., Whittle, L., Thornton, J., Lim, C., Bradford, D., Yamakawa, Y., Leon, M., Brener, N., & Ethier, K. A. (2018). Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2017. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries, 67(8), 1–114. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1

- Kephart, L., Setodji, C., Pane, J., Shadel, W., Song, G., Robertson, J., Harding, N., Henley, P., & Ursprung, W. W. S. (2020). Evaluating tobacco retailer experience and compliance with a flavoured tobacco product restriction in Boston, Massachusetts: impact on product availability, advertisement and consumer demand. Tob Control, 29(e1), e71–e77. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055124

- Kim, H. Y. (2017). Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics, 42(2), 152–155. https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2017.42.2.152

- Kong, G., Bold, K. W., Simon, P., Camenga, D. R., Cavallo, D. A., & Krishnan-Sarin, S. (2017). Reasons for cigarillo initiation and cigarillo manipulation methods among adolescents. Tobacco Regulatory Science, 3(2), 48–58. https://doi.org/10.18001/TRS.3.2(Suppl1).6

- Kong, G., Cavallo, D. A., Goldberg, A., LaVallee, H., & Krishnan-Sarin, S. (2018). Blunt use among adolescents and young adults: informing cigar regulations. Tobacco Regulatory Science, 4(5), 50–60. https://doi.org/10.18001/TRS.4.5.5

- Lee, K. J., & Carlin, J. B. (2010). Multiple imputation for missing data: Fully conditional specification versus multivariate normal imputation. American Journal of Epidemiology, 171(5), 624–632. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwp425

- Lemyre, A., Poliakova, N., & Belanger, R. E. (2019). The relationship between tobacco and cannabis use: A review. Substance Use & Misuse. 54(1), 130–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2018.1512623

- Lipperman-Kreda, S., Islam, S., Wharton, K., Finan, L. J., & Kowitt, S. D. (2022). Youth tobacco and cannabis use and co-use: Associations with daily exposure to tobacco marketing within activity spaces and by travel patterns. Addictive Behaviors. 126, 107202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107202

- MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130–149. [Database] https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130

- Mantey, D. S., Onyinye, O. N., & Montgomery, L. (2021). Prevalence and correlates of daily blunt use among U.S. African American, Hispanic, and White adults from 2014 to 2018. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 35(5), 514–522. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000702

- Mauro, P. M., Carliner, H., Brown, Q. L., Hasin, D. S., Shmulewitz, D., Rahim-Juwel, R., Sarvet, A. L., Wall, M. M., & Martins, S. S. (2018). Age differences in daily and nondaily cannabis use in the United States, 2002–2014. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 79(3), 423–431. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2018.79.423

- Mayer, M. E., Kong, G., Barrington-Trimis, J. L., McConnell, R., Leventhal, A. M., & Krishnan-Sarin, S. (2020). Blunt and non-blunt cannabis use and risk of subsequent combustible tobacco product use among adolescents. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 22(8), 1409–1413. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntz225

- Meier, E., & Hatsukami, D. K. (2016). A review of the additive health risk of cannabis and tobacco co-use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 166, 6–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.07.013

- Montgomery, L. (2015). Marijuana and tobacco use and co-use among African Americans: results from the 2013, National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Addictive Behaviors. 51, 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.046

- National Academy of Sciences Engineering and Medicine (NASEM). (2017). The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: The current state of evidence and recommendations for research. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28182367

- Nyman, A. L., Sterling, K. L., Majeed, B. A., Jones, D. M., & Eriksen, M. P. (2018). Flavors and risk: perceptions of flavors in little cigars and cigarillos among U.S. adults, 2015. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 20(9), 1055–1061. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntx153

- Odani, S., Armour, B., & Agaku, I. T. (2020). Flavored tobacco product use and its association with indicators of tobacco dependence among US adults, 2014–2015. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 22(6), 1004–1015. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntz092

- Peters, E. N., Rosenberry, Z. R., Schauer, G. L., O’Grady, K. E., & Johnson, P. S. (2017). Marijuana and tobacco cigarettes: Estimating their behavioral economic relationship using purchasing tasks. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 25(3), 208–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/pha0000122

- Phan, L., McNeel, T. S., & Choi, K. (2021). Prevalence of current large cigar versus little cigar/cigarillo smoking among U.S. adults, 2018–2019. Preventive Medicine Reports, 24, 101534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101534

- Public Health Law Center. (2021). Countering the tobacco epidemic: Menthol and other flavored products. Retrieved January 31, from https://www.publichealthlawcenter.org/topics/commercial-tobacco-control/menthol-and-other-flavored-products

- Pulvers, K., Ridenour, C., Woodcock, A., Savin, M. J., Holguin, G., Hamill, S., & Romero, D. R. (2018). Marijuana use among adolescent multiple tobacco product users and unique risks of dual tobacco and marijuana use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 189, 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.04.031

- Rogers, T., Feld, A., Gammon, D. G., Coats, E. M., Brown, E. M., Olson, L. T., Nonnemaker, J. M., Engstrom, M., McCrae, T., Holder-Hayes, E., Ross, A., Boles Welsh, E., Guardino, G., & Pearlman, D. N. (2019). Changes in cigar sales following implementation of a local policy restricting sales of flavoured non-cigarette tobacco products. Tobacco Control, 29(4), 412–419. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055004

- Rose, S. W., Amato, M. S., Anesetti-Rothermel, A., Carnegie, B., Safi, Z., Benson, A. F., Czaplicki, L., Simpson, R., Zhou, Y., Akbar, M., Younger Gagosian, S., Chen-Sankey, J. C., & Schillo, B. A. (2020). Characteristics and reach equity of policies restricting flavored tobacco product sales in the United States. Health Promotion Practice, 21(1_suppl), 44S–53S. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839919879928

- Rosenberry, Z. R., Schauer, G. L., Kim, H., & Peters, E. (2017). The use of flavored cigars to smoke marijuana in a sample of US adults co-using cigarettes and marijuana. Tobacco Regulatory Science, 3(2), 94–100. https://doi.org/10.18001/TRS.3.2(Suppl1).10

- Rostron, B. L., Cheng, Y. C., Gardner, L. D., & Ambrose, B. K. (2020). Prevalence and reasons for use of flavored cigars and ENDS among US youth and adults: Estimates from wave 4 of the PATH study, 2016–2017. American Journal of Health Behavior, 44(1), 76–81. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.44.1.8

- Schauer, G. L., & Peters, E. N. (2018). Correlates and trends in youth co-use of marijuana and tobacco in the United States, 2005–2014. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 185, 238–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.12.007

- Schlienz, N. J., & Lee, D. C. (2018). Co-use of cannabis, tobacco, and alcohol during adolescence: Policy and regulatory implications. International Review of Psychiatry, 30(3), 226–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2018.1465399

- Seaman, E. L., Green, K. M., Wang, M. Q., Quinn, S. C., & Fryer, C. S. (2019). Examining prevalence and correlates of cigarette and marijuana co-use among young adults using ten years of NHANES data. Addictive Behaviors. 96, 140–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.04.014

- Seaman, E. L., Howard, D. E., Green, K. M., Wang, M. Q., & Fryer, C. S. (2019). A sequential explanatory mixed methods study of young adult tobacco and marijuana co-use. Substance Use & Misuse. 54(13), 2177–2190. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2019.1638409

- Seaman, E. L., Stanton, C. A., Edwards, K. C., & Halenar, M. J. (2020). Use of tobacco products/devices for marijuana consumption and association with substance use problems among U.S. young adults (2015–2016). Addictive Behaviors. 102, 106133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106133

- Setodji, C. M., Martino, S. C., Gong, M., Dunbar, M. S., Kusuke, D., Sicker, A., & Shadel, W. G. (2018). How do tobacco power walls influence adolescents? A study of mediating mechanisms. Health Psychology, 37(2), 188–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000558

- Smith, C. L., Cooper, B. R., Miguel, A., Hill, L., Roll, J., & McPherson, S. (2021). Predictors of cannabis and tobacco co-use in youth: Exploring the mediating role of age at first use in the population assessment of tobacco health (PATH) study. Journal of Cannabis Research, 3(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42238-021-00072-2

- Sorensen, G., Emmons, K., Hunt, M. K., Barbeau, E., Goldman, R., Peterson, K., Kuntz, K., Stoddard, A., & Berkman, L. (2003). Model for incorporating social context in health behavior interventions: Applications for cancer prevention for working-class, multiethnic populations. Preventive Medicine, 37(3), 188–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00111-7

- Sterling, K. L., Fryer, C. S., & Fagan, P. (2016). The most natural tobacco used: A qualitative investigation of young adult smokers’ risk perceptions of flavored little cigars and cigarillos. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 18(5), 827–833. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntv151

- Sterling, K. L., Fryer, C. S., Nix, M., & Fagan, P. (2015). Appeal and impact of characterizing flavors on young adult small cigar use. Tobacco Regulatory Science, 1(1), 42–53. https://doi.org/10.18001/TRS.1.1.5

- Sterling, K. L., Jones, D. M., Majeed, B., Nyman, A. L., & Weaver, S. R. (2019). Affect predicts small cigar use in a national sample of US young adults. Tobacco Regulatory Science, 5(3), 253–263. https://doi.org/10.18001/TRS.5.3.4

- Stevens, J. P. (1992). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

- Timberlake, D. S., Rhee, J., Silver, L. D., Padon, A. A., Vos, R. O., Unger, J. B., & Andersen-Rodgers, E. (2021). Impact of California’s tobacco and cannabis policies on the retail availability of little cigars/cigarillos and blunt wraps. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 228, 109064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109064

- Trapl, E. S., & Koopman Gonzalez, S. J. (2018). Attitudes and risk perceptions toward smoking among adolescents who modify cigar products. Ethnicity & Disease, 28(3), 135–144. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.28.3.135

- Trapl, E. S., Koopman Gonzalez, S. J., Cofie, L., Yoder, L. D., Frank, J., & Sterling, K. L. (2016). Cigar product modification among high school youth. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 20(3), ntw328–376. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntw328

- Truth Initiative. (2021). Flavored tobacco policy restrictions as of December 31, 2021

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (2021). FDA commits to evidence-based actions aimed at saving lives and preventing future generations of smokers. Retrieved April 29, from https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-commits-evidence-based-actions-aimed-saving-lives-and-preventing-future-generations-smokersv

- Villanti, A. C., Johnson, A. L., Ambrose, B. K., Cummings, K. M., Stanton, C. A., Rose, S. W., Feirman, S. P., Tworek, C., Glasser, A. M., Pearson, J. L., Cohn, A. M., Conway, K. P., Niaura, R. S., Bansal-Travers, M., & Hyland, A. (2017). Flavored tobacco product use in youth and adults: findings from the first wave of the PATH study (2013–2014). American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53(2), 139–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.026

- Vuolo, M., Lindsay, S. L., & Kelly, B. C. (2022). Further consideration of the impact of tobacco control policies on young adult smoking in light of the liberalization of cannabis policies. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 24(1), 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntab149

- Wang, J. B., Ramo, D. E., Lisha, N. E., & Cataldo, J. K. (2016). Medical marijuana legalization and cigarette and marijuana co-use in adolescents and adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 166, 32–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.06.016

- Weinberger, A. H., Wyka, K., Kim, J. H., Smart, R., Mangold, M., Schanzer, E., Wu, M., & Goodwin, R. D. (2022). A difference-in-difference approach to examining the impact of cannabis legalization on disparities in the use of cigarettes and cannabis in the United States, 2004-17. Addiction, 117(6), 1768–1777. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15795

- West, S. G., Taylor, A. B., & Wu, W. (2012). Model fit and model selection in structural equation modeling. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press.