Abstract

Background: Peer influence on risky behavior is particularly potent in adolescence and varies by gender. Smoking prevention programs focused on peer-group leaders have shown great promise, and a social influence model has proven effective in understanding adult smoking networks but has not been applied to adolescent vaping until 2023. This work aims to apply a social influence model to analyze vaping by gender in a high school network. Methods: A high school’s student body was emailed an online survey asking for gender, age, grade level, vape status, and the names of three friends. Custom Java and MATLAB scripts were written to create a directed graph, compute centrality measures, and perform Fisher’s exact tests to compare centrality measures by demographic variables and vape status. Results: Of 192 students in the school, 102 students responded. Students who vape were in closer-knit friend groups than students who do not vape (p < .05). Compared to males who vape, females who vape had more social ties to other students who vape, exhibiting greater homophily (p < .01). Compared to females who do not vape, females who vape were in closer-knit friend groups (p < .05) and had more ties to other students who vape (p < .01). Conclusion: Differences in vaping by social connectedness and gender necessitate school and state policies incorporating the social aspect of vaping in public health initiatives. Large-scale research should determine if trends can be generalized across student bodies, and more granular studies should investigate differences in motivations and social influence by demographic variables to individualize cessation strategies.

Background

From 2016–2023, the percentage of high schoolers using combustible cigarettes decreased from 8% to 3.9% (Birdsey et al., Citation2023; Cullen et al., Citation2019). On the other hand, e-cigarette use initially rose from 11.3% to 27.5% among high schoolers and 4.3% to 10.5% among middle schoolers before decreasing to 10% and 4.6%, respectively, partly due to public health campaigns against flavored e-cigarettes (Birdsey et al., Citation2023; Cooper et al., Citation2022; Jones & Salzman, Citation2020). Despite a significant decrease among high schoolers, there was no significant change in middle school e-cigarette use from the year before (Birdsey et al., Citation2023). Additionally, despite cessation, nicotine exposure inhibits adolescent brain development and increases the risk of psychiatric disorders and cognitive impairment later in life (England et al., Citation2015; Goriounova & Mansvelder, Citation2012). Thus, adolescent nicotine use remains a salient issue.

Research has revealed the importance of dyadic and group-level social relationships in understanding initiation and continuation of smoking behavior (Chen et al., Citation2001; Powell et al., Citation2005), and a growing body of literature has started to examine these relationships using larger social networks. One pattern that can be observed by leveraging social network theory is homophily (McPherson et al., Citation2001), the tendency to choose friends who exhibit similar behaviors. Adults who smoke are friends with people who smoke and grow more distant within their larger social networks (Blok et al., Citation2017; Christakis & Fowler, Citation2008). Given fundamental differences between adults and adolescents and adolescent vape dependence only recently moving to the forefront of public health studies (Kong & Krishnan-Sarin, Citation2017), applying adult-based strategies to address adolescent nicotine consumption may be insufficient (Bailey et al., Citation2009).

The social influence model, specifically involving peer leaders, has shown promise when applied to high school-based smoking prevention programs (Flay, Citation2009). Having fewer substance-using peers in schools can reduce the likelihood of exposing other students to risk factors (Cleveland & Wiebe, Citation2003). However, the applicability of the social influence model for school-based vaping prevention has not yet been studied in detail; only the impact of vape control policies has been addressed (Milicic et al., Citation2018). This gap necessitates a bridge between adolescent-specific methodology and the social influence model to study social influences on vaping.

Valente et al. (Citation2023) was the first study to apply a social influence model to analyze vaping in high school networks. Valente et al.’s (Citation2023) findings from one Midwestern U.S. school district indicated that adolescents choose friends of the same gender, and adolescents who vape choose friends who vape (i.e. exhibit gender and vaping homophily). Given the novelty of applying social network theory to vaping among high school students, this article aims to investigate vaping homophily by gender in a Northeastern U.S. school, help identify unique challenges involved in studying adolescent vaping behaviors, and explore future directions for applying social network analysis to this population.

Methods

Survey

One high school’s administrators were asked to email a survey to which students could voluntarily assent with no promise of compensation. The survey included gender, age, level of education, vape status, and peer influence status. Vape status was positive if the student responded “true” to vaping at least once every 2 weeks. Students were also asked to list three friends in their high school in order of decreasing strength of the friendship (friendship tie strength of one being weakest [i.e. friend listed last] and three being strongest). The students were restricted to choosing three ties because respondents given more than three choices may select friends to whom they believe they should be connected (e.g. more popular people) rather than indicate their true friends (De Nooy et al., Citation2018). Influence status was a binary choice considered positive if the student responded true to, “I think my friends heavily influence my actions.”

Analysis

Pajek was used to create a network graph with de-identified nodes spaced out according to centrality using the spring-based Kamada-Kawai energy function (Kamada & Kawai, Citation1989). The percentage of students who vape across the other survey variables was calculated. The number and average strength of social ties were calculated for every student in the network. Fisher’s exact tests assessed associations between vaping and gender, age, grade level, influence status, average tie strength, and average number of ties. Proportion of ties to students who vape by gender was calculated to assess homophily. Weighted clustering coefficient is a measure of how interconnected friends are. It is calculated by the proportion of one’s friends who are also friends with each other, accounting for friendship strength. Student’s t-tests compared homophily scores and clustering coefficients by vape status and gender (https://github.com/njha02/surveyAnalysis).

Results

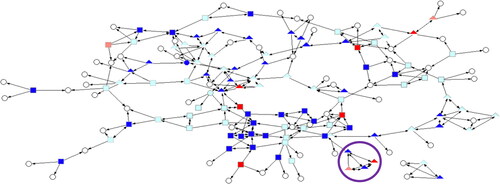

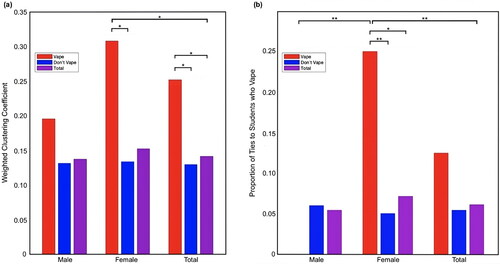

Of 192 students in the high school, 102 students responded (; Suppl. Table 1; ). There was no significant association between vaping and gender, age, grade level, influence status, tie strength, and number of ties (). Students who vape exhibited a higher clustering coefficient and were thus in closer-knit friend groups than students who do not vape (; Suppl. Table 2). Although the same number of males and females vape at least once every 2 weeks, males who vape were scattered throughout the school network while females who vape exhibited a higher proportion of ties to students who vape, indicating greater homophily ( and ; Suppl. Table 2). Compared to females who do not vape, females who vape were in closer-knit friend groups () and had more ties to other students who vape (). Of note, one female in-group exhibited unique network characteristics: one female student who does not vape bridges the other three female students to the rest of the network ().

Figure 1. High school network by gender, vape status, and self-reported susceptibility to peer influence.

Triangle: Female; Square: Male; Circle: Other gender identity; White circle: Did not respond but in a respondent’s friend list; Dark blue: Do not vape and believe they are influenced by peers; Cyan: Do not vape and believe they are not influenced; Bright red: Vape and believe they are influenced Light mango: Vape and believe that they are not influenced; Purple circle denotes a closed network of female students bridged by one student.

Figure 2. Weighted clustering coefficient (a) and proportion of ties to respondents who vape (b) by gender and Vape Status. *p < .05; **p<.01

Table 1. Vape status by gender, age, grade level, self-reported peer-influence status, average tie strength, and average number of ties.

Discussion

Taking previous findings of homophily among adolescents who vape one step further, we show that adolescents who vape are in closer-knit networks, and females who vape exhibit more homophily than males who vape in this school. Prior work has shown that females can be more susceptible to peer influence on deviant behavior without parental supervision (Svensson, Citation2003) and are more likely to form close-knit rather than extensive networks (David-Barrett et al., Citation2015). In-groups allow group identity to reinforce preferences, impose excessive demands for group conformity, and face fewer challenges to their norms from alternative influences outside the in-group (Ellwardt et al., Citation2020; Kondo et al., Citation2012). This might have been the case for the female in-group of this study. Therefore, it is essential to determine if female students who vape are more likely to be tied to other students who vape across other schools. Peer group vaping prevention strategies may prove effective for female high schoolers, while male students may benefit more from a person-centered approach.

There remains a gap in understanding internal factors of adolescent vaping. In a study of teens and adults switching from combustible to electronic cigarettes, females more often sought to control undesirable moods and were more likely to be recommended by friends, while males were more likely to switch due to curiosity and maintenance of positive reinforcers (Piñeiro et al., Citation2016). Additionally, we found that some high schoolers may exhibit insight into the fact that they are influenced by peers yet continue to partake in peer-influenced behaviors. More granular studies are needed to create new objective metrics and determine differences in motivation (e.g. vaping for relief or reward, fitting in socially, etc.) and perceived peer-influence status by demographics to individualize cessation strategies. Findings from these studies can inform the development of personalized primary and tertiary prevention for vaping and nicotine use disorder among youth.

Limitations

Accurately surveying minors, especially considering the vaping epidemic’s rise within the last decade (Jones & Salzman, Citation2020), is unique. As such, the scientific community has not yet optimized novel methodology, and the self-reported status of vaping constitutes a limitation. Although anonymous self-reported smoking habits have proven reliable among adults (Dolcini et al., Citation1996), participants in the study may have under-reported usage due to fear of legal or parental repercussions. Respondents were not asked to report vaping propensities of their social ties because adolescents’ perceptions of peer substance use tend to be biased (Henry et al., Citation2011). However, other aspects of a school-based approach are compelling, such as low selection bias and high response rate (Helweg-Larsen & Bøving-Larsen, Citation2003). Students have been previously required by their high school to answer questions on substance use. Although challenging to implement ethically, the social influence survey may be modified to obtain integral social influence data and may prove vital to maximizing the response rate in future studies.

Despite most students responding to the survey in the school, the small sample size limited generalization. The sample may not be representative of U.S. high schoolers since only one school was surveyed. Additionally, the small sample of 10 students who vape might introduce bias into reported gender differences, but even if there is some degree of social desirability or self-selection bias, the percentage of respondents who vape (9.8%) matches the national average of 10% (Birdsey et al., Citation2023).

Our pilot study serves to guide future work rather than establish definitive trends. Gathering data on a particular school might inform intervention for that school’s student body even if the results do not apply to other schools. Along with survey responses themselves, creative methods to use untapped network information and calculate other centrality measures should be explored. For instance, many students who did not take the survey were listed as close ties to the 53% of students who did respond, giving a reasonable approximation of the positions of 160 students (83%), which could potentially be better incorporated into the network using predictive models. Future studies should determine what proportion of the network should be encapsulated to produce accurate results while balancing the logistical challenges of contacting administrators/students and achieving a satisfactory response rate. Since this study is limited by its focus on only one school, future research should also establish longitudinal trends across student bodies while accounting for differences between schools (e.g. U.S. census region, public/private, urban/rural, Social Vulnerability Index, etc.).

Conclusion

Applying social network theory can reveal previously untapped information to address vaping among a unique student body. Since females and males who vape exhibit different network characteristics, public health entities and schools should explore person-centered intervention strategies that incorporate individual traits and social information. Optimizing high school vaping prevention programs will likely require balancing an overarching framework for all schools and intervention specific to each school’s student body. This work supports a general framework for assessing peer-influenced behavior and highlights the importance of translating findings to adapt evidence-based intervention strategies.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (24.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (27.4 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nalin Jha and Nishant Jha for software assistance as well as Andrew Cherlin for his mentorship.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bailey, S. R., Harrison, C. T., Jeffery, C. J., Ammerman, S., Bryson, S. W., Killen, D. T., Robinson, T. N., Schatzberg, A. F., & Killen, J. D. (2009). Withdrawal symptoms over time among adolescents in a smoking cessation intervention: Do symptoms vary by level of nicotine dependence? Addictive Behaviors, 34(12), 1017–1022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.06.014

- Birdsey, J., Cornelius, M., Jamal, A., Park-Lee, E., Cooper, M. R., Wang, J., Sawdey, M. D., Cullen, K. A., & Neff, L. (2023). Tobacco product use among U.S. middle and high school students—National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2023. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 72(44), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7244a1

- Blok, D. J., de Vlas, S. J., van Empelen, P., & van Lenthe, F. J. (2017). The role of smoking in social networks on smoking cessation and relapse among adults: A longitudinal study. Preventive Medicine, 99, 105–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.02.012

- Chen, P.-H., White, H. R., & Pandina, R. J. (2001). Predictors of smoking cessation from adolescence into young adulthood. Addictive Behaviors, 26(4), 517–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4603(00)00142-8

- Christakis, N. A., & Fowler, J. H. (2008). The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. The New England Journal of Medicine, 358(21), 2249–2258. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa0706154

- Cleveland, H. H., & Wiebe, R. P. (2003). The moderation of adolescent-to-peer similarity in tobacco and alcohol use by school levels of substance use. Child Development, 74(1), 279–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00535

- Cooper, M., Park-Lee, E., Ren, C., Cornelius, M., Jamal, A., & Cullen, K. A. (2022). Notes from the field: E-cigarette use among middle and high school students—United States, 2022. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 71(40), 1283–1285. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7140a3

- Cullen, K. A., Gentzke, A. S., Sawdey, M. D., Chang, J. T., Anic, G. M., Wang, T. W., Creamer, M. L. R., Jamal, A., Ambrose, B. K., & King, B. A. (2019). e-cigarette use among youth in the United States, 2019. JAMA, 322(21), 2095–2103. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.18387

- David-Barrett, T., Rotkirch, A., Carney, J., Behncke Izquierdo, I., Krems, J. A., Townley, D., McDaniell, E., Byrne-Smith, A., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2015). Women favour dyadic relationships, but men prefer clubs: Cross-cultural evidence from social networking. PloS One, 10(3), e0118329–e0118329. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118329

- De Nooy, W., Mrvar, A., & Batagelj, V. (2018). Exploratory social network analysis with Pajek: Revised and expanded edition for updated software. Structural analysis in the social sciences (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108565691

- Dolcini, M. M., Adler, N. E., & Ginsberg, D. (1996). Factors influencing agreement between self-reports and biological measures of smoking among adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 6(4), 515–542.

- Ellwardt, L., Wittek, R. P. M., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2020). Social network characteristics and their associations with stress in older adults: Closure and balance in a population-based sample. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 75(7), 1573–1584. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbz035

- England, L. J., Bunnell, R. E., Pechacek, T. F., Tong, V. T., & McAfee, T. A. (2015). Nicotine and the developing human. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49(2), 286–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.015

- Flay, B. R. (2009). School-based smoking prevention programs with the promise of long-term effects. Tobacco Induced Diseases, 5(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1617-9625-5-6

- Goriounova, N. A., & Mansvelder, H. D. (2012). Short- and long-term consequences of nicotine exposure during adolescence for prefrontal cortex neuronal network function. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 2(12), a012120–a012120. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a012120

- Helweg-Larsen, K., & Bøving-Larsen, H. (2003). Ethical issues in youth surveys: Potentials for conducting a national questionnaire study on adolescent schoolchildren’s sexual experiences with adults. American Journal of Public Health, 93(11), 1878–1882. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.11.1878

- Henry, D., Kobus, K., & Schoeny, M. (2011). Accuracy and bias in adolescents’ perceptions of friends’ substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 25(1), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021874

- Jones, K., & Salzman, G. A. (2020). The vaping epidemic in adolescents. Missouri Medicine, 117(1), 56–58. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32158051

- Kamada, T., & Kawai, S. (1989). An algorithm for drawing general undirected graphs. Information Processing Letters, 31(1), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-0190(89)90102-6

- Kondo, N., Suzuki, K., Minai, J., & Yamagata, Z. (2012). Positive and negative effects of finance-based social capital on incident functional disability and mortality: An 8-year prospective study of elderly Japanese. Journal of Epidemiology, 22(6), 543–550. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20120025

- Kong, G., & Krishnan-Sarin, S. (2017). A call to end the epidemic of adolescent E-cigarette use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 174, 215–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.001

- McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 415–444. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415

- Milicic, S., DeCicca, P., Pierard, E., & Leatherdale, S. T. (2018). An evaluation of school-based e-cigarette control policies’ impact on the use of vaping products. Tobacco Induced Diseases, 16(August), 35. https://doi.org/10.18332/tid/93594

- Piñeiro, B., Correa, J. B., Simmons, V. N., Harrell, P. T., Menzie, N. S., Unrod, M., Meltzer, L. R., & Brandon, T. H. (2016). Gender differences in use and expectancies of e-cigarettes: Online survey results. Addictive Behaviors, 52, 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.09.006

- Powell, L. M., Tauras, J. A., & Ross, H. (2005). The importance of peer effects, cigarette prices and tobacco control policies for youth smoking behavior. Journal of Health Economics, 24(5), 950–968. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2005.02.002

- Svensson, R. (2003). Gender differences in adolescent drug use: The impact of parental monitoring and peer deviance. Youth & Society, 34(3), 300–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X02250095

- Valente, T. W., Piombo, S. E., Edwards, K. M., Waterman, E. A., & Banyard, V. L. (2023). Social network influences on adolescent e-cigarette use. Substance Use & Misuse, 58(6), 780–786. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2023.2188429