We present a commentary on the recent publication by Kim et al. (Citation2024). The study is a secondary analysis of a subsample of the ADJUSST dataset. The ADJUSST study is comprised of N = 55,414 adults (21+) who purchased a JUUL Starter Kit between June and October of 2018 (Shiffman et al., Citation2021). The Kim article (Kim et al., Citation2024) analyzed a subsample of the ADJUSST cohort (N = 12,537) who reported smoking: (a) 100+ cigarettes in their lifetime, (b) in the past 30 days, and (c) every day or some days, at baseline. We propose that critical flaws in the primary dataset (ADJUSST), the sample and outcomes selection for secondary analysis, and omissions of meaningful information in Kim et al. (Citation2024) render the results uninterpretable.

Commentary 1: The ADJUSST Study has an undisclosed response rate that was likely below 10%

The ADJUSST study recruited N = 55,414 participants via two mechanisms: (1) placing invitation cards inside 500,000 JUUL Starter Kits (JSKs) distributed to tobacco retailers across the US; and (2) e-mailing an undisclosed number of digital invitations to adults who purchased JSKs via the manufacture (JUUL Labs Inc.) website. Lack of information on number of digital invitations prohibits a calculation of the response rate. However, we attempt to estimate the response rate for the ADJUSST study using previous publications by JUUL Labs (Goldenson et al., Citation2021; Shiffman & Hannon, Citation2023).

Methods for recruitment were only briefly described in the primary source article published in the JUUL-sponsored supplemental edition of the American Journal of Health Behavior (2021) (Shiffman et al., Citation2021). To estimate the response rate for the Kim et al. (Citation2024) study, we assume that 33.7% of all ADJUSST participants were recruited via digital invitation (Goldenson et al., Citation2021) with a 20% response rate, using publications in this special issue (Shiffman & Hannon, Citation2023). These figures suggest that ∼93,375 digital invitations were sent and N = 18,675 ADJUSST participants were recruited. Added to the 500,000 retail invitations, this would reflect a response rate of 9.3% (55,414/593,375); presented in .

Table 1. Estimated invitations and response rate for ADJUSST Study.

As response rate declines, potential bias due to systematic differences between respondents (i.e., recruited participants) and non-respondents increases (Draugalis & Plaza, Citation2009). Per Draugalis and Plaza (Citation2009): “Nonresponse bias can seriously compromise the validity of results. For example, if 50% of subjects responded in a particular way to a specific item, the ‘true’ percentages could actually range from 45%-55% if the overall response rate was 90%, but range from 5%-95% if the overall response rate was only 10%” (Draugalis & Plaza, Citation2009). The actual response rate for this study was not provided or even discussed by Kim et al. (Citation2024), including no assessment of the potential impact that the same could have on the results.

Commentary 2: Less than 5% of all those who purchased JUUL Starter Kits were “switched” away from cigarette smoking

The Kim article reports that N = 2,708 ADJUSST participants transitioned from established cigarette smokers to non-cigarette smokers (i.e., “switching”) at 6-, 9-, and 12-month follow-up. This “switching” rate reflects 21.6% of the sample included in their secondary analysis (N = 12,537) but only 11.8% of established smokers at baseline (N = 22,905). While Kim et al. (Citation2024) present a narrative of success, findings must be contextualized within the broader spectrum of smoking cessation, where established treatments such as varenicline and nicotine patches report higher continuous abstinence rates at 6 months (e.g., 25.5% for varenicline, 18.5% for nicotine patch) (Anthenelli et al., Citation2016; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Citation2020). Conversely, the reported “switching” rate among established smokers is comparable to the rate for placebo in other clinical trials (Rigotti et al., Citation2022).

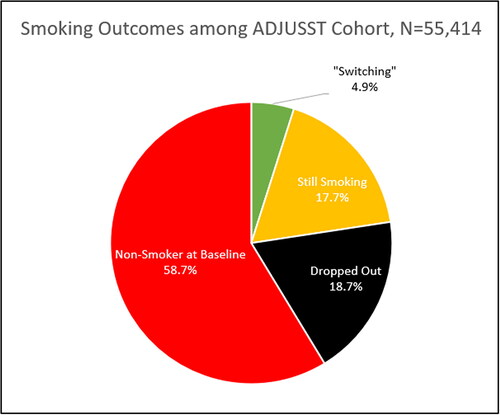

More alarming is that participants enrolled into the ADJUSST study (58.7%) were not established cigarette smokers when they purchased the JUUL Starter Kit (i.e., baseline) (Shiffman et al., Citation2021). In fact, ∼9.5% of ADJUSST participants (n = 5,234) were never smokers, ∼23.3% (n = 12,952) were ever users who had smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime (i.e., “experimental smokers”), and 20.1% were considered former cigarette smokers, at baseline. Put another way, the N = 2,708 cigarette smokers who reported “switching” reflect just 4.9% of all of the ADJUSST study participants (N = 55,414); as seen in .

Figure 1. Cigarette Smoking among The Adult JUUL Switching and Smoking Trajectories (ADJUSST) Study.

Consequently, it is necessary to quantify how many of the N = 2,708 established cigarette smokers who stopped smoking were replaced by never, experimental, and former smokers who reported initiation, escalation, or re-uptake of cigarette smoking between baseline and 12-month follow-up. For example, study of the ADJUSST cohort reported that ∼8.8% of baseline nonsmokers became past 30-day cigarette smokers at 12-month follow-up (i.e., “reverse switching”) (Shiffman & Holt, Citation2021).

Commentary 3: Most established smokers became dual users of JUUL and combustible cigarettes

Per the Food and Drug Administration (FDA): “Switching completely to e-cigarettes can reduce health risks among adults who smoke. But continued use of both products (“dual use”) does not meaningfully reduce one’s risk.” Kim reports that 78.4% of established smokers continued to smoke cigarettes across one or more follow-ups, and 90% to 99% of all participants sustained JUUL use over the course of the ADJUSST study; thus, most smokers continued to use both products. Further, Kim reports that between 50%-70% of dual users reported daily JUUL use at various follow-up surveys. Another study of the ADJUSST data found that ∼9.6% dual cigarette smokers/JUUL users increased the number of cigarettes smoked per day, and 31.3% did not reduce the number of cigarettes smoked per day at 12-month follow-up (Selya et al., Citation2021).

Taken together, these studies of the ADJUSST dataset show that most established cigarette smokers who began using JUUL are unlikely to quit smoking and are at-risk for becoming dual users with increased markers of dependence (i.e., daily use) for both products. Dual users are likely to consume a larger total daily dose of nicotine without meaningfully reducing risk for negative health effects (Czoli et al., Citation2019; Pisinger & Rasmussen, Citation2022) and quitting smoking becomes more difficult for dual users (Jackson et al., Citation2020).

Conclusion

Evidence from the ADJUSST study, as reported by Kim et al. Kim et al., Kim et al., (Citation2024) indicates that a fraction of smokers—just 11.8% of all ADJUSST established smokers at baseline—self-reported transitions to exclusive e-cigarette use using JUUL. Moreover, JUUL appears to have adopted strategic ambiguity in their messaging that allows them to claim a public health benefit to their product. JUUL has specifically claimed that “ENDS are not smoking cessation medications,” Shiffman and Goldenson (Citation2023) further suggesting that “the process of smoking cessation treatment is like a crash diet program,” while “the process of switching with ENDS is like a lifestyle diet change” (Shiffman & Goldenson, Citation2023). This characterization of switching to e-cigarettes dangerously oversimplifies the multifaceted challenge of overcoming nicotine addiction and not only trivializes the difficult journey most smokers experience while trying to quit, but also ignores the significant lack of evidence regarding the long-term health impacts of e-cigarettes. What is known is that JUUL delivers an extremely high dose of nicotine, so is “ultimately, a highly addictive vaping product” (Prochaska et al., Citation2021). This messaging not only undermines the regulatory framework designed to protect public health but also potentially misleads the public about the efficacy and safety of e-cigarettes, not only for youth and tobacco-naive individuals—but also for adults.

While limited evidence suggests that e-cigarettes might offer cessation benefits over nicotine replacement therapy in a controlled, clinical setting (Lindson et al., Citation2024), it is important to note that the real-world effectiveness of e-cigarettes for smoking cessation remains uncertain; and this evidence is not specific to JUUL. For example, Osibogun et al. (Citation2020) reported in their analysis of the PATH cohort study over two years that only 19.1% of adult dual smokers either quit (12.1%) or reduced harm by switching to less harmful alternatives (7.0%). In contrast, a significant majority (55.2%) reverted back to exclusive cigarette smoking, while 25.7% maintained their dual usage habits (Osibogun et al., Citation2020). This is particularly troubling as a review of the health effects of real-world dual use of e-cigarettes and cigarettes (Pisinger & Rasmussen, Citation2022) suggests that dual users consume the same amount of tobacco or more compared to those who exclusively smoke conventional cigarettes, and that dual users expose themselves to not only the harmful substances in tobacco smoke, but harmful substances from e-cigarettes whose long-term health effects are not yet known.

In conclusion, we strongly encourage a re-analysis of the ADJUSST data to account for the full scope of “switching” and “reverse switching” patterns. While Kim et al. (Citation2024) makes a point to distinguish their paper from consideration as a smoking cessation study, their outcome (smoking abstinence) and sample (established smokers) only offers the utility of exploring cessation, which they label as “switching.” To responsibly report on past 30-day abstinence (i.e., “switching”), the study would also need to contextualize these findings with those who switched from nonsmokers or experimental smokers to cigarette smoking (i.e., “reverse switching”), and consider the potential impact of dual use. Finally, JUUL's assertions of harm reduction should be scrutinized in light of the potential risks their products pose to youth, young adults, and adults.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anthenelli, R. M., Benowitz, N. L., West, R., St Aubin, L., McRae, T., Lawrence, D., Ascher, J., Russ, C., Krishen, A., & Evins, A. E. (2016). Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet (London, England), 387(10037), 2507–2520. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30272-0

- Czoli, C. D., Fong, G. T., Goniewicz, M. L., & Hammond, D. (2019). Biomarkers of exposure among “dual users” of tobacco cigarettes and electronic cigarettes in Canada. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 21(9), 1259–1266. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/nty174

- Draugalis, J. R., & Plaza, C. M. (2009). Best practices for survey research reports revisited: Implications of target population, probability sampling, and response rate. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 73(8), 142. https://doi.org/10.5688/aj7308142

- Goldenson, N. I., Shiffman, S., Hatcher, C., Lamichhane, D., Gaggar, A., Le, G. M., Prakash, S., & Augustson, E. M. (2021). Switching away from cigarettes across 12 months among adult smokers purchasing the JUUL system. American Journal of Health Behavior, 45(3), 443–463. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.45.3.4

- Jackson, S. E., Shahab, L., West, R., & Brown, J. (2020). Associations between dual use of e-cigarettes and smoking cessation: a prospective study of smokers in England. Addictive Behaviors, 103, 106230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106230

- Kim, S., Shiffman, S., & Goldenson, N. I. (2024). Adult smokers’ complete switching away from cigarettes at 6, 9, and 12 months after initially purchasing a JUUL e-cigarette. Substance Use & Misuse, 59(5), 805–815. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2024.2303990

- Lindson, N., Butler, A. R., McRobbie, H., Bullen, C., Hajek, P., Begh, R., Theodoulou, A., Notley, C., Rigotti, N. A., Turner, T., Livingstone-Banks, J., Morris, T., & Hartmann-Boyce, J. (2024). Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1(1), CD010216. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub8

- Osibogun, O., Bursac, Z., Mckee, M., Li, T., & Maziak, W. (2020). Cessation outcomes in adult dual users of e-cigarettes and cigarettes: The Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health cohort study, USA, 2013–2016. International Journal of Public Health, 65(6), 923–936. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-020-01436-w

- Pisinger, C., & Rasmussen, S. K. B. (2022). The health effects of real-world dual use of electronic and conventional cigarettes versus the health effects of exclusive smoking of conventional cigarettes: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13687. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013687

- Prochaska, J. J., Vogel, E. A., & Benowitz, N. (2021). Nicotine delivery and cigarette equivalents from vaping a JUULpod. Tobacco Control, 31(e1), e88–e93. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056367

- Rigotti, N. A., Kruse, G. R., Livingstone-Banks, J., & Hartmann-Boyce, J. (2022). Treatment of tobacco smoking: A review. JAMA, 327(6), 566–577. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.0395

- Selya, A. S., Shiffman, S., Greenberg, M., & Augustson, E. M. (2021). Dual use of cigarettes and JUUL: Trajectory and cigarette consumption. American Journal of Health Behavior, 45(3), 464–485. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.45.3.5

- Shiffman, S., & Goldenson, N. (2023). A Stages of Change analysis of movement towards stopping smoking in a cohort of adult smokers adopting JUUL.

- Shiffman, S., & Hannon, M. J. (2023). Switching away from smoking at 12 months among adult JUUL users varying in recent history of quit attempts made with and without smoking cessation medication. Drug Testing and Analysis, 15(10), 1281–1296. https://doi.org/10.1002/dta.3551

- Shiffman, S., & Holt, N. M. (2021). Smoking trajectories of adult never smokers 12 months after first purchase of a JUUL starter kit. American Journal of Health Behavior, 45(3), 527–545. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.45.3.8

- Shiffman, S., Sembower, M. A., Augustson, E. M., Goldenson, N. I., Haseen, F., McKeganey, N. P., & Russell, C. (2021). The Adult JUUL Switching and Smoking Trajectories (ADJUSST) study: Methods and analysis of loss-to-follow-up. American Journal of Health Behavior, 45(3), 419–442. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.45.3.3

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Smoking cessation. A report of the surgeon general.