Abstract

Objective

The relation is investigated between situational drinking norms which accept heavier drinking and the experience of harm from others’ drinking. How does the experience of such harm relate to the acceptance of heavier drinking in drinking situations?

Methods

Respondents in a 2021 combined sample from random digitally dialed mobile phones and a panel survey of Australian adults (n = 2,574) were asked what level of drinking is acceptable in 11 social situations, including 3 “wet” situations where drinking is generally acceptable. Besides their own drinking patterns, respondents were also asked about their experience of harm from others’ drinking in the last 12 months. Focussing on respondents’ answers concerning the wetter situations, regression analyses were used to examine the relation between experiencing such harm and views on how much drinking was acceptable in the situations.

Results

Heavier drinkers were more likely to have experienced harm from others’ drinking. Among heavier drinkers, those who experienced such harm generally did not differ significantly in their normative acceptance of any drinking in “wet” situations but were more accepting of drinking enough to feel the effects.

Discussion

From these cross-sectional results, experiencing harm from others’ drinking does not seem to result in less acceptance of drinking to intoxication; rather, experiencing such harm was associated with more acceptance of heavy drinking. However, these findings may be the net result of influences in both directions, with the acceptance of intoxication in wet situations being more common among heavier drinkers, whose drinking exposes them to harm from others’ drinking.

Introduction

Drinking alcoholic beverages is a largely social activity, and whether and how much alcohol is consumed in given circumstances is strongly influenced by social rules and expectations for that situation—what sociologists call situational drinking norms and psychologists call injunctive norms (Kuntsche et al., Citation2020). Earlier sociological research on drinking norms was primarily conducted in Finland and the United States (Room, Citation1975), with a general finding, later shown to be applicable also elsewhere (Room et al., Citation2019), that there are clearly “dryer” situations where there is considerable consensus that there should be no drinking, for instance, when about to drive a car or when looking after small children, and “wetter” situations where drinking is acceptable to many people (and indeed there are some expectations of relatively heavy drinking), such as at a party at a friend’s home or when meeting up with old friends at a tavern. There are, of course, many situations falling in between these two categories.

Studies of the US general population adopted a procedure of asking respondents about how much drinking was acceptable in a range of situations, with some from the “wetter” and some from the “dryer” ends of the range, and several situations also from in between (e.g., Greenfield & Room, Citation1997). In the cross-national GENACIS surveys (Wilsnack et al., Citation2009), the US approach to measuring situational drinking norms was adapted for international use, and it was used in Australia in a Victorian general population sample in 2007 (Dietze et al., Citation2013). A GENACIS analysis of such samples in 12 countries found each society made substantial distinctions between “dryer” and “wetter” situations in expectations of the acceptability both of drinking at all and of drinking “enough to feel the effects”. However, within each society there is generally more consensus between abstainers and heavier drinkers on not drinking in dryer situations, while there is less consensus between them on the acceptability of drinking enough to feel the effects in wetter situations. In comparisons between the societies, responses on the norms were generally more favorable to drinking in Australia than in most of the other societies studied. Thus Australia was among the societies with the least proportions specifying no drinking as the norm in “dryer” situations and was one of only two societies with clear majorities that drinking enough to feel the effects was OK in the “wetter” situations (Room et al., Citation2019).

In recent years, there has been a substantial renewal of attention to the harms of drinking to others around the drinker, with a substantial body of research on this emerging not only in Australia but internationally (Laslett et al., Citation2019b). A new Australia-wide population survey primarily focused on harms from others’ drinking was undertaken in 2021 (Laslett et al., Citation2023). Included in its questionnaire was a selection of 11 questions on situational norms for drinking, with three situations which might be considered “wetter” and 3 “dryer”, and the rest in between.

A common finding in studies of harms from others’ drinking is that heavier drinkers suffer these harms at least as often as others do, and in fact often experience higher rates of harm (e.g. Laslett et al., Citation2019b). To some extent, this reflects that the social nature of much drinking means that heavier drinkers often find themselves around other heavier drinkers. Their relatively high rates of harm from others’ drinking raises the question of whether the experience of such harm changes the heavier drinker’s views on drinking norms. Thus those who have experienced such harm might change their views of drinking norms in wetter situations, and become less likely to respond that it’s OK in the situation to “drink enough to feel the effects” or to get drunk. While there are relevant studies of change in perception of drinking norms among US college students (e.g., Lewis & Neighbors, Citation2006; Lee et al., Citation2010), this issue appears not to have been previously considered in terms of effects of personal experience on normative responses in a general-population context. Previous studies of the effects of efforts to change drinking norms in heavy-drinking subcultures have been focused on the collective level (Room et al., Citation2022). In this exploratory study, we consider evidence from Australia on the potential effect of personal adverse experiences on normative responses concerning situational drinking and discuss the potential meaning of the findings.

Materials and methods

Survey data

Cross-sectional survey data were collected from two subsamples of Australians aged 18 and over: (a) respondents recruited in random digit dialing (RDD) calls to Australian mobile phone numbers (n = 1,000); and (b) a sample drawn from the Life in Australia™ (LinA) survey panel (Kaczmirek et al., Citation2019) (n = 1,574). Fieldwork on both subsamples was conducted in November and December, 2021. As discussed in Laslett et al. (Citation2023), widespread and dramatic decreases in response rates to older survey methods have forced changes in population survey methodology. Despite the decline in response rates, there is some evidence that with appropriate fieldwork techniques and weighting, there is not necessarily an increase in non-response bias. Thus each of the two subsamples when weighted were found to be a fair reflection of the Australian adult population and to reflect the various segments of the population when used unweighted (Social Research Centre Citation2021; Social Research Centre Citation2022). A methodological study comparing the results of analyses on the two subsamples found few significant differences in results (Rintala et al., Citation2023). The survey and study were approved by La Trobe University’s Human Ethics Research Committee (HEC20518).

All 2,574 participants were asked about the harms they had experienced in the past 12 months from the drinking of families, friends and coworkers, and strangers, as well as a variety of demographic and other attitudinal and behavioral questions, including about their own drinking and their views on whether and how much drinking was OK in different situations (situational drinking norms).

Measures

The survey instrument took an average of 30 min to complete and was adapted from an earlier 2008 survey (Wilkinson et al., Citation2009). The fieldwork was conducted by a specialist market research and data collection agency (the Social Research Center - SRC).

Demographics

Gender

Participants reported the following response categories: “female”, “male”, “non-binary/gender fluid” or “different identity”. Gender was recoded as female (=2) and male (=1); due to a small number of responses (a total of 17), the other gender categories were excluded from the gender-specific analyses.

Age

Age was recoded into three categories: 18-34 (=1), 35-64 (=2), and 65+ (=3). These age categories approximate life stages with different patterns of living and alcohol consumption: early adulthood, midlife, and senior and retirement age.

Education level

Participants were asked: “what is your highest level of education or training that you’ve completed?”. Responses ranged from “no formal schooling” to “Postgraduate Degree/Masters/Doctoral degree” and were recoded as “<high school completion” (=1), “high school completion/some tertiary” (=2), and “bachelor’s degree and above” (=3).

Urbanicity

Respondents reported on where they were living at the time of the survey. These responses were recoded as “capital city” (=1) and “rest of the state” (=2).

Employment status

Participants were asked: “which of the following best describes your job situation?”. The survey fieldwork was conducted during the substantial disruptions of employment during the COVID-19 emergency, which resulted in a relatively high proportion of respondents who were currently “furloughed” from their regular employment. Responses were coded as “currently working” (=1), “furloughed” (=2), and “not working” (=3), with this last category including those who are retired.

Risky drinking behavior and situational norms

Risky drinking frequency

Participants who reported any alcohol consumption in the last 12 months were asked “how often do you have five standard drinks or more?”. Responses ranged from “Never” to “Every day” and were recoded as “Abstainer” (=0) (i.e., respondents who reported never drinking or who did not drink/ceased drinking in the last 12 months), “Never/not in the last 12 months” (=1), “Less often than monthly” (=2), “1-3 times in a month” (=3), and “At least weekly” (=4).

Situational drinking norms: Wet situation norms

Participants were asked to report on “how much drinking is alright” in 11 situations, including 3 “wet” situations (e.g., “at a party, at someone else’s home), 5 “in-between situations” (e.g., “at home on a weekday night”), and 4 “dry situations” (e.g., “when driving a car”). Responses ranged from “no drinking” (scored as 1) through “one or two drinks” (scored 2) and “it’s OK to drink enough to feel the effects” (scored 3) to “getting drunk is sometimes alright” (scored 4). For this study, we were only interested in norms on drinking in the three wet situations—besides “at a party at someone else’s house”, these were “when with friends at home”, and “out at a bar or pub having drinks with friends”. A summary total score for the respondent’s answers on these three wet situations was used for the present analyses. The score for current drinkers ranged from 3-12, with a score of 7.5 or more roughly meaning that a majority of respondents in the category thought it was OK to drink at least “enough to feel the effects” on average across the three situations.

Harm from others’ drinking

Participants were asked several series of questions on the impacts of others’ drinking on their lives in the past 12 months.

Harm from known others

Participants reported experiences of harm from a household member (partner, housemate, family member in household) or someone else known to them (e.g., work colleague, family member, etc.) in the past 12 months. A dichotomous variable was created from the responses: any experience of harm =1, otherwise 0.

Harm from strangers

Participants reported on the experience of each of 11 harms due F their drinking from people that they did not know (see Laslett et al., Citation2023). A dichotomous variable was created with any reported experience of stranger harm = 1, otherwise 0.

Any harm from others

A dichotomous variable was created that combined the aforementioned categories, such that any experience of harm from anyone’s drinking, whether strangers or known others = 1, otherwise 0.

Statistical analyses

In order to answer our key research question regarding drinking norms, and as we were concerned here not with rates in the population but with relationships between variables such as situational drinking norms and experience of harm from drinking, we used unweighted data.

First, to examine variations in the acceptability of drinking in wet situations, the mean wet situation norm score was compared across demographic variables, risky drinking frequency and experience of harm to others. Two-sample t-tests and one-way ANOVAs were conducted to determine significant differences between group means in population subgroups.

Second, to investigate whether the relationship between experience of harm and normative acceptance of heavy drinking in wet situations was different for those who drink more frequently or sometimes drink at riskier levels, a further analysis examines the interaction of these three variables. We conducted three linear regression models with the interaction risky drinking frequency*experience of harm from others, adjusting for education, employment, age and gender. The marginal predicted means were plotted to examine the relationships. All analyses were conducted in STATA 18.0 (StataCorp, Citation2023).

Results

Of the 2,515 respondents in the combined samples who responded to the 3 wet items, 10.6% drank 5+ drinks on an occasion at least once a week, 14.3% drank 5+ drinks 1-3 times a month, 18.4% drank 5+ on an occasion less often than monthly, and 56.7% were either drinkers who never drink 5+ drinks on an occasion or were abstainers.

shows the mean wet norm score by demographics, risky drinking status and experience of harm to others. Men were significantly more accepting of drinking in wet situations than women. Likewise, those aged 65 and over were significantly less accepting of drinking in wet situations than both those aged 18 to 34 and those aged 35 to 64. Those who reported currently working had a significantly higher acceptability of drinking than those who were furloughed or not working. Regarding the respondent’s risky drinking frequency, those reporting any risky drinking in the past 12 months assented to significantly higher wet drinking situation norms than those not drinking at risky levels at all in the past 12 months. Those who experienced any harm from the drinking of others, whether from someone known to them or from a stranger, also gave a significantly higher endorsement of drinking in wet situations than those who reported no harm from each category.

Table 1. Mean score on how much drinking is acceptable in wet situations by demographics, risky drinking frequency and experience of harm from others’ drinking.

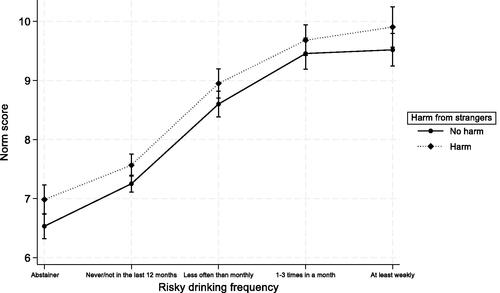

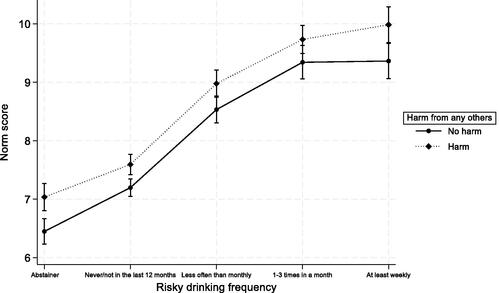

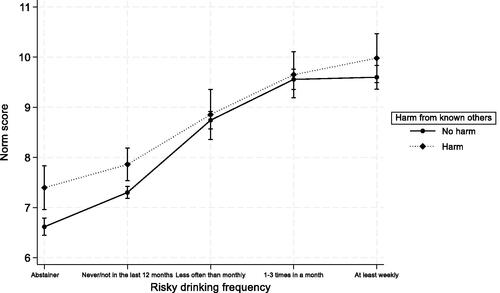

To further investigate the relationship between risky drinking frequency, experience of harm from others’ drinking, and norm endorsement, three interaction models showing the level of wet drinking situation norm endorsement for those with and without harm from others’ drinking in different categories of risky drinking frequency are shown in . In addition, Supplementary Tables 1–3 provide the results of the multivariable regression models. For all three models, the respondent’s frequency of risky drinking is strongly associated with wet drinking situational norm endorsement. However, there is little differentiation in the situational norm endorsement by whether the respondent experienced harm from others’ drinking in the past year. The differences are generally in the direction of higher wet drinking situational norms for those experiencing harm from others’ drinking, but the difference is only significant in two categories for those experiencing harm from known others (i.e., among those who drink 5+ drinks less often than monthly or 1–3 times a month).

Figure 1. Wet situational drinking norms, by risky drinking and harm from known others’ drinking: Multivariable regression, controlling for gender, age group, employment and education.

Discussion

Experiencing harm from others’ drinking is not associated with reduced acceptance of drinking to intoxication in relatively wet situations. In fact, the relationship tends in the opposite direction: those who have experienced harm from others in the last year are significantly more likely to accept that getting drunk is sometimes OK in such situations.

In part, this relationship reflects that those who accept heavier drinking in the situations are often themselves heavier drinkers. It has been a common finding in other studies in Australia and elsewhere that experience of harm from others’ drinking is more common in those who are themselves relatively heavy drinkers (Laslett et al., Citation2019a; Moan et al., Citation2015; Sundin et al., Citation2021).

The data analyzed here is of course cross-sectional in its collection, so that any relationships found cannot be assumed to be causal. If a negative relation between the experience of harms from others’ drinking and acceptance of intoxication had been found, it might be hypothesized that the negative experience had pushed against normative acceptance of the behavior. A positive relationship, such as we have found, can be interpreted in terms of the attitudes accepting of intoxication making it more likely that those holding them would put themselves in situations where they are exposed to the possibility of harm from others’ drinking. Of course, both causal explanations could have some validity: the empirical cross-sectional findings on the relationship could be the net effect of attitudes influencing behavior and of behavioral experience influencing attitudes. It will take longitudinal data to begin to test the extent of action of the alternative causal pathways.

In the meantime, the finding that acceptance of situational heavy drinking is associated with a greater risk of harm from others’ drinking holds some potential implications for practice. Brief interventions, counseling or therapy for heavier drinkers might identify the risks not only from one’s own drinking but from others’ particularly in heavier drinking situations. Most therapeutic interventions for quitting or cutting down on drinking include advice to avoid places and situations where drinking is expected. The advice might be augmented to include advice to change ideas and norms on acceptable levels of drinking in “wet” situations.

Situations dr norms - Supplementary Materials - 29 Feb 2024.docx

Download MS Word (61.4 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Social Research Centre for the fieldwork and its documentation, and Jade Rintala for her assistance with documenting and handling the data at CAPR. The project is funded by the Australian Research Council grant (LP19190100698), “Alcohol’s harm to others: patterns, costs, disparities and precipitants”. The partners and co-funders of this grant are the Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education (FARE), Australian Rechabite Foundation, Australasian College of Emergency Medicine (ACEM), Alcohol and Drug Foundation (ADF), Australian Institute of Family Studies, Monash Health, Central Queensland University and La Trobe University. Laslett and Room are funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant “Alcohol’s harm to Others” (GNT2016706). Anderson-Luxford is supported by La Trobe University Postgraduate Research Scholarship.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare, beyond the receipt of funding declared above.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Dietze, P., Ferris, J., & Room, R. (2013). Who suggests drinking less? Demographic and national differences in informal social controls on drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 74(6), 859–866. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2013.74.859

- Greenfield, T., & Room, R. (1997). Situational norms for drinking and drunkenness: Trends in the U.S. adult population, 1979–1990. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 92(1), 33–47.

- Kaczmirek, L., Phillips, B., Pennay, D. W., Lavrakas, P. J., & Neiger, D. (2019). Building a probability-based online panel: Life in Australia. CSRM & SRC methods paper. Available at: https://csrm.cass.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/docs/2019/7/Building-aprobability-based-online-panel-Life-in-Australia.pdf.

- Kuntsche, S., Room, R., & Kuntsche, E. (2020). I can keep up with the best”: The role of social norms in alcohol consumption and their use in interventions. In: Frings, D. & Albery, I.P., eds., Alcohol Handbook: Understandings from Synapse to Society, pp. 285–302. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-816720-5.00024-4

- Laslett, A.-M., Room, R., Waleewong, O., Stanesby, O. & Callinan, S., eds. (2019a). Harm to Others from Drinking: Patterns in Nine Societies. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/329393

- Laslett, A.-M., Stanesby, O., Callinan, S., & Room, R. (2019b). A first look across the nine societies: Patterns of harm from others’ drinking. In: Laslett, A.-M., Room, R., Waleewong, O., Stanesby, O. & Callinan, S., eds., Alcohol’s Harms to Others: A Cross-National Study, pp. 215–233. World Health Organization.

- Laslett, A.-M., Room, R., Kuntsche, S., Anderson-Luxford, D., Willoughby, B., Doran, C., Jenkinson, R., Smit, K., Egerton-Warburton, D., & Jiang, H. (2023). Alcohol’s harm to others in 2021: Who bears the burden? Addiction (Abingdon, England), 118(9), 1726–1738. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16205

- Lee, C. M., Geisner, I. M., Patrick, M. E., & Neighbors, C. (2010). The social norms of alcohol-related negative consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 24(2), 342–348. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018020

- Lewis, M. A., & Neighbors, C. (2006). Social norms approaches using descriptive drinking norms education: A review of the research on personalized normative feedback. Journal of American College Health: J of ACH, 54(4), 213–218. https://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.54.4.213-218

- Moan, I. S., Storvoll, E. E., Sundin, E., Lund, I. O., Bloomfield, K., Hope, A., Ramstedt, M., Huhtanen, P., & Kristjánsson, S. (2015). Experienced harm from other people’s drinking: A comparison of Northern European countries. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 9(Suppl. 2), 45–57. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.4137/SART.S23504 https://doi.org/10.4137/SART.S23504

- Rintala, J., Room, R., Smit, K., Jiang, H., & Laslett, A.-M. (2023). The 2021 Alcohol’s Harm to Others Survey: Methodological approach. International Journal of Alcohol and Drug Research, 10(2), 48–56. https://ijadr.org/index.php/ijadr/article/view/483/625) https://doi.org/10.7895/ijadr.483

- Room, R. (1975). Normative perspectives on alcohol use and problems. Journal of Drug Issues, 5(4), 358–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204267500500407

- Room, R., Kuntsche, S., Dietze, P., Munné, M., Monteiro, M., & Greenfield, T. (2019). Testing consensus about situational norms on drinking: A cross-national comparison. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 80(6), 651–659. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2019.80.651

- Room, R., MacLean, S., Dwyer, R., Pennay, A., Turner, K., & Saleeba, E. (2022). Changing risky drinking practices in different types of social worlds: Concepts and experiences. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy, 29(1), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2020.1820955

- Social Research Centre. (2021). Life in Australia™ - Wave 55 Technical Report.

- Social Research Centre. (2022). Harm to Others Mobile random digit dial component – Technical summary.

- StataCorp. (2023). Stata Statistical Software: Release 18. StataCorp LLC.

- Sundin, E., Galanti, M. R., Landberg, J., & Ramstedt, M. (2021). Severe harm from others’ drinking: A population-based study on sex differences and the role of one’s own drinking habits. Drug and Alcohol Review, 40(2), 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13202

- Wilkinson, C., Laslett, A.-M., Ferris, J., Livingston, M., Mugavin, J., & Room, R. (2009). The Range and Magnitude of Alcohol’s Harm to Others: Study design, data collection procedures and measurement. Fitzroy: AER Centre for Alcohol Policy Research. Turning Point Alcohol & Drug Centre. https://doi.org/10.26181/5b84e8af52b61

- Wilsnack, R. W., Wilsnack, S. C., Kristjanson, A. F., Vogeltanz-Holm, N. D., & Gmel, G. (2009). Gender and alcohol consumption: Patterns from the multinational GENACIS project. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 104(9), 1487–1500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02696.x