Abstract

Background

Authors discuss the connections between novel psychoactive substance (NPS) use and psychological trauma. The transition from classical substances to NPS, a paradigm change, poses a challenge for the treatment systems. Objective: Research evidence suggests difficulties in emotion regulation and trauma-related NPS-use. Authors explore some demographic and psychopathological characteristics related to such findings and examine the connections between emotion regulation deficiency and the choice of substance.

Method

This study uses a methodological triangulation of a biologically identified sample to confirm NPS use, a survey method to describe users’ socioeconomic characteristics, and Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-2) subscales to study dysfunctions in emotion regulation.

Results

Participants (77 patients) were mainly polydrug users. The transgenerational transfer of substance use was a salient feature, but material deprivation was not characteristic of the entire sample. NPS use was not connected to certain psychopathological characteristics the way classical substance use was. More than half of the respondents had elevated scores on MMPI-2 Demoralization (RCd) and Dysfunctional Negative Emotions (RC7) scales. Nearly half of them also scored high on Neuroticism/Negative Emotionality (NEGE).

Conclusions

Results suggest that NPS use in the context of polydrug use is connected to psychological trauma and emotion regulation deficiency, but the MMPI-2 scales to assess emotional dysfunctions are not connected to a particular type of NPS.

1. Introduction: Novel psychoactive substance use as a paradigm change

The transition from classical substances to novel psychoactive substances (NPS) continues to be a challenging phenomenon globally (Schifano et al., Citation2015; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Citation2013). A handbook on the two most popular NPSs, synthetic cathinones (SCH) and synthetic cannabinoids (SCB) discusses three main aspects of NPS use: classification, users’ groups, and new harms elicited by the new substances (Abdulrahim & Bowden-Jones, Citation2015). These cheap substances rapidly found their way to new user groups as well as to the users of classical, legal, or illegal substances. By 2010, widespread NPS use in Hungary brought about unexpected and serious health hazards, such as overdose fatalities, nosocomial infections and acute psychotic disturbances related to drug intoxication (Schifano et al., Citation2015). Rácz et al. (Citation2016) documented the rapid transition from opiate use to NPS use as a paradigm change, bringing about recurrent experiences of inadequacy on part of the medical care systems, prepared for the treatment of opiate users mainly.

Internet-based global networks played a key role in the expeditious spread of NPS. As Kaló & Felvinczi (Citation2017) argue, NPSs appeared simultaneously with the broadband internet and smartphones, which altered the communication forms and channels related to substance use. NPSs spread fast in rural settings in Hungary—traditionally, areas of heavy and high-risk alcohol use but relatively free from illegal drug use. According to the results of a 2019 survey, published in the yearly report of the Hungarian National Focal Point (Citation2020), lifetime prevalence of marijuana use was 6,1%, while ecstasy and synthetic cannabinoids use was 2,5% and 2,1%, respectively. Amphetamines had a share of 1,5%, cocaine 1,5%, and designer stimulants ranked the seventh with a share of 1,4%. Csorba et al. (Citation2017) performed a toxicological analysis of residues from injecting paraphernalia in a sample of 4109 objects. They identified more than 200 different substances, including five previously unknown ones. Synthetic cathinones (SCH) were present in 2347 cases.

An EU funded international research (Kaló & Felvinczi, Citation2017) among SCH and SCB users focused on their subjective perceptions concerning substance use. In the study, two distinct groups of users emerged. SCB users usually smoke the product, the frequency of use is sporadic, and the context of use is highly varied. They often take the drug for its assumed health-related or other special attributes. Middle-class persons are motivated by peer-pressure or use SCB for recreational purposes. Low-income or no-income users take SCB as a healthier alternative to SCH. SCH users are almost exclusively marginalized intravenous users with several health-related problems. Episodes of auto- and hetero-aggression are frequent among them.

The varied, unpredictable composition of SCH available in the domestic drug market results in a high variability of symptoms, such as paranoia, euphoria, tactile and other hallucinations, a psychotic level of anxiety and extreme muscle cramps. Previous research has offered the suggestion that marginalized persons with low socioeconomic status may use SCH or SCB in order to achieve a total dissociative state and get away from the high-level stress and hopelessness that surrounds them (Csák et al., Citation2020; Van Hout et al., Citation2018). “Escape from reality” patients may look for an alternative to everyday life struggles and are primarily driven by the pursuit of joy and pleasure through drug abuse. Their use is situational, relatively rare, and is characterized mainly by heterogenous social and peer-related motives (Kaló & Felvinczi, Citation2017).

In conclusion, NPS use poses high risks on several groups with very different socioeconomic background and motivations (Alves et al., Citation2020; European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Citation2016; Martinotti et al., Citation2014; Tamama & Lynch, Citation2020). Yet, relatively little is known about these groups as they are not easy to reach. Users’ psychosocial characteristics are an under-researched area, due to some challenging methodological problems. Users cannot be contacted while intoxicated; and are usually not motivated to participate in any research. Patients who receive in-patient treatment and therefore are more accessible to participate in a controlled study are few; and their narratives are inevitably influenced by the local therapeutic discourse. The reliability of self-report data on SUD is only around 40 per cent (McKernan et al., Citation2015). The existing studies usually focus on socioeconomic factors, the types of substances, or—using a small qualitative sample—on users’ experiences (Kaló et al., Citation2020; Kassai et al., Citation2017).

1.1. NPS use, psychological trauma and emotion regulation

Studies have suggested a strong connection between SUD, psychological trauma, and emotion regulation deficits (Van den Brink, Citation2015). In this section, authors focus on these interrelations to consider their potential significance in NPS use. Emotion regulation is an ability to recognize, identify, evaluate, control, or modify one’s emotional reactions (Kostiuk & Fouts, Citation2002). Emotion regulation problems, understood as the failure to regulate or tolerate negative emotions, are closely associated with interpersonal trauma, and its frequent consequence, posttraumatic stress disorder, PTSD (Dvir et al., Citation2014; Nagulendran & Jobson, Citation2020). Kassai and associates (2017) in their phenomenological analysis identified SCB use as a particular type of psychological trauma. SUD, as an “externalizing pattern characterized by impulsivity” (Wolf et al., Citation2008, p. 231) and PTSD may co-occur (Dvir et al., Citation2014; Hien et al., Citation2022; Roberts, Citation2021; Van den Brink, Citation2015). „Comorbidity between PTSD and SUD is common: amongst individuals with SUD, the prevalence of lifetime PTSD ranges from 26% to 52%”, further, „Poor capacity for emotion regulation has been found to be associated with PTSD SUD comorbidity” (Roberts et al., Citation2015, pp. 26–27). Sensation-seeking attitude as a motive for using—frequently misunderstood as sign of pure hedonism, a “cool life” by laypersons—was found to be related to sexual abuse in childhood by Werb et al. (Citation2015). Persons with SUD may experience emptiness, alternating with an unmanageable flood of emotions, the dissociation of emotion and thought, and problems in recognizing own emotions (Bateman & Fonagy, Citation2019; Fonagy et al., Citation2002). The consequences of mentalization failures include the unmanageability of intense negative emotions, such as anxiety and anger (Bateman & Fonagy, Citation2019).

Khantzian (Citation2011) interpreted substance use as self-medication, an escape from dysphoria rather than the quest for euphoria. He worked out a typology on one’s drug of choice, relating the use of depressants, stimulants, and opiates to different psychopathologies. In this view, substance use serves to control helpless states, negative feelings, loss of meaning in life and low self-evaluation. For persons with SUD, hangovers yield an explanation for their sufferings, and for the (assumed or real) negative reactions from their environment (Khantzian, Citation1985, Citation1997, Citation2011; Roberts et al., Citation2015). Koski-Jännes (Citation2004) focussed on the automatisms related to one’s efforts to cope with deficits in emotion regulation: “much of the cognitive and emotion regulation of addiction takes place without awareness, and even when conscious processing does occur, it often serves the purpose of defending and bolstering the destructive attachment” (p. 61). She claimed that the model of self-medication did not include social factors; further, it was based on a simple linear causality, which failed to grasp the complexity of the phenomenon.

In this study, one of the methods is the use of MMPI-2 RC Scales so we briefly comment on the previous findings concerning the use of these scales to study problems in emotion regulation. Scales RCd, RC1, RC2 and RC7 are used to assess psychological dysfunctions in affective functioning. RC4 and RC9 are related to the domains of behavior, and RC3, RC6, RC8, to those of thought (Forbey & Ben-Porath, Citation2008). As Finn and Kamphuis (Citation2006, p. 204) concluded, “the RC Scales open up links to a vast domain of relevant personality and emotion research. Specifically, the RC Scales connect the MMPI–2 to a widely accepted model of affect (…)”. Sellbom & Ben-Porath (Citation2005) found that RC2 had a strong negative correlation with positive emotionality, while RC7 had a strong correlation with negative emotionality. RCd, an “emotionally coloured dimension” (Archer, Citation2006, p. 180; Tellegen et al., Citation2003, p. 12) negatively correlated with positive emotionality and positively correlated with negative emotionality. Moreover, RCd and RC2 were consistently correlated with collateral medical data indicating depression, suicidality, various vegetative symptoms, and feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness. RC7 was also associated with the collateral variables related to depression and suicide. Inpatients with elevated scores on RC7 were more likely to report poor concentration, flashbacks, and feelings of helplessness and hopelessness (Arbisi et al., Citation2008). „RC7 is considered a measure of negative emotionality rather than being specific to anxiety” (Sellbom et al., Citation2006, p. 204). Current conceptualizations and measures of depression are close to Demoralization (RCd), comprising symptoms related to both negative and low positive affect (Osberg et al., Citation2008). The component specific to depression is anhedonia/low positive emotionality (Sellbom et al., Citation2006). The scales associated with negative emotionality (RCd, RC7) and RC9 were associated with juvenile conduct problems and violence disinhibition confidence, commonly occurring among persons with SUD. Further, RC4 was significantly related to criminal history, juvenile conduct problems, substance use, partner violence, and violence disinhibition confidence (Sellbom et al., Citation2008).

2. Research questions

Previous evidence suggests a relationship between trauma-related substance use, and serious difficulties in the processing and managing of emotional contents. We analyze the results of MMPI-2 RC and PSY-5 Scales, focussing mainly on the scales that are directly related to emotion regulation. In relation to self-medication hypothesis, we examine the connections between emotion regulation deficiencies and the choice of substance.

3. Design and methods

3.1. Sample

Participants were contacted by the first author at a Hungarian hospital ward and three in-patient rehabilitation centers. The sample is a purposive, total population sample of 77 persons, all of them at the beginning of their treatment, right after the detoxification phase (about one week). SCH or SCB use was confirmed by gas or liquid chromatography on a biological sample, or a recent toxicological report (within the preceding 6 months). Persons who (1) produced a negative drug test for NPSs, (2) had not finished the 5th grade of elementary school (a criterion for administering MMPI-2) (3) were experiencing acute psychotic states or were living with a general learning disability were excluded from the sample. Respondents were informed by the first author about the study and all of them agreed to participate. Ethical approval was issued by the University of Pécs, on the condition that respondents’ anonymity is ensured (PTE KK RIKEB, 2019. 05. 02.).

3.2. Method

This study uses a methodological triangulation:

Biological samples to confirm NPS use

A survey method to describe respondents’ socioeconomic characteristics: The survey questionnaire comprised basic questions on respondents’ age, gender, and level of education. Authors also asked about parental drug use as an important socialization factor, the respondents’ choice of drugs, and the level of material deprivation. The first author administered the questionnaire.

Restructured Clinical Scales and the PSY-5 Scales drawn from the Hungarian translation of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-2) (Butcher et al., Citation2001) to study dysfunctions in emotion regulation: This version is the most recent standardized measure in the domestic context (MMPI-2-RF is not available; neither is automatic scoring) (see ). Our exclusion criteria regarding MMPI-2 validity scales were the following: CNS: > =10 (CanNotSay); VRIN: > =79; TRIN: > =79; F: <39 and >79 outpatient setting, inpatient setting <54 and >79; Fp: > =99.

Table 1. MMPI-2 scales connected to emotion regulation.

The MMPI-2 was administered by the first author.

3.2.1. Data integration

Beyond a descriptive analysis using the above methods for a more comprehensive picture on this under-researched population, we plan to identify correlations between the type of substance and MMPI-2 RC and PSY-5 Scales to see if the use of a particular substance is related to the scales.

4. Results

4.1. Results of the socioeconomic survey

The sample included 16 women and 61 men, with an age range between 18 and 45 (M = 29.52; SD = 6.95). Data on main socioeconomic status (SES) characteristics are summarized in .

Table 2. Patient demographics.

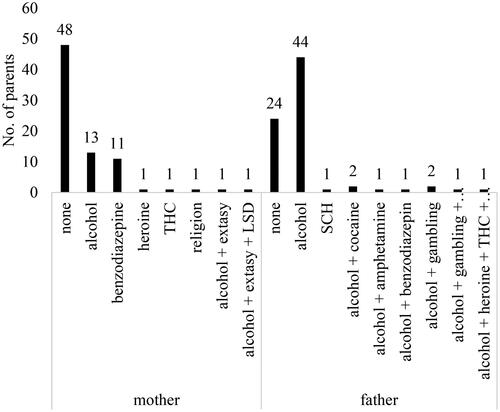

Data on parental substance use are based on participants’ reports and use was identified as a common problem (see ).

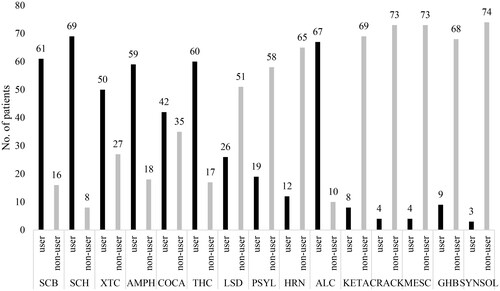

Data on respondents’ own substance use, based on biological tests, either at the time of data collection or verified during prior medical treatment, are presented in . Polydrug use was a major characteristic of the sample. Both the classical and the new psychoactive substances were represented.

Figure 2. Substance use.

Note: Substances - (1) synthetic cannabinoids; (2) synthetic cathinones; (3) extasy; (4) amphetamine; (5) cocaine; (6) cannabis; (7) LSD; (8) psilocybin; (9) heroine; (10) alcohol; (11) ketamine; (12) crack cocaine; (13) mescaline.

The results of MMPI-2 on emotion regulation are presented in . High, clinically significant scores for three of the scales were characteristic of approximately half of the respondents: Demoralization, Dysfunctional Negative Emotions, and Neuroticism/Negative Emotionality.

Table 3. MMPI-2 pathological cases connected to Restructured Clinical Scales (RC) and PSY-5 Scales.

4.2. Data integration: Substance use and MMPI-2 scales related to emotion regulation

Cocaine, THC and LSD use were related to certain aspects of emotion regulation. Cocaine use had a negative correlation with Demoralization (r=-0.253; p = 0.03; p < 0.05), and with Dysfunctional Negative Emotions (r=-0.238; p = 0.04; p < 0.05). THC use negatively correlated with Introversion - Low Positive Emotionality scale (r=-0.245; p = 0.03; p < 0.05), and LSD use positively correlated with Demoralization (r = 0.230; p = 0.04; p < 0.05) and Dysfunctional Negative Emotions (r = 0.283; p = 0.01; p < 0.05) (see and ).

Table 4. Correlations between substance use and Restructured Clinical Scales (Rc).

Table 5. Correlations between substance use and PSY-5 Scales.

A significant regression equation was found between Cocaine and Demoralization (F(1,75)=5.122; p = 0.03; p < 0.05), with an R2 of .064. This means that Cocaine predicted 6,4% of Demoralization variances. A significant regression equation was found between Cocaine and Dysfunctional Negative Emotions as well (F(1,75)=4.499; p = 0.04; p < 0.05), with an R2 of 0.057, that is, Cocaine predicted 5,7% of Dysfunctional Negative Emotions variances. Likewise, a significant regression equation was found between THC and Introversion - Low Positive Emotionality (F(1,75)=4.776; p = 0.03; p < 0.05), with an R2 of 0.060, showing that THC predicted 6% of Introversion - Low Positive Emotionality variances. Furthermore, there was a significant regression equation between LSD and Demoralization (F(1,75)=4.179; p = 0.04; p < 0.05), with an R2 of 0.053, thus, LSD predicted 5,3% of Demoralization variances. Lastly, we saw a significant regression equation between LSD and Dysfunctional Negative Emotions (F(1,75)=6.547; p = 0.01; p < 0.05), with an R2 of 0.080: LSD predicted 8% of Dysfunctional Negative Emotions variances.

5. Discussion

This research explored clinically relevant information on a group of NPS users in Hungary at the beginning of their treatment. The gender rate of respondents (about 1:3) can be compared to the gender rates of lifetime prevalence for illicit drug use in 2019, which was 19,9% for men and 8% for women (Hungarian National Focal Point, Citation2020). Women have less chances for treatment as men do, as female users are usually exploited and battered sex workers, in addition, a woman with SUD faces heavier stigma than a man does (Kaló, Citation2020).

Material deprivation was present with more than half of the patients, but many had an adequate level of education. This could challenge the idea that NPS use is mainly the result of material deprivation (Csák et al., Citation2020). However, persons in this sample were included in treatment that is less accessible for those living in rural areas and/or are characterized by lower levels of education. Parental divorce rate in the sample roughly corresponds to the Hungarian average. Respondents reported frequent parental substance use, especially alcohol use—a source of childhood traumatization, neglect, and abuse. Alcohol use is a traditional and heavy problem in Hungary (Elekes, Citation2014). In this sample, both parents’ substance (alcohol) use is above the average, and parents probably serve as role models for substance-related problems.

The respondents are polydrug users, and their preferred substances include new and classical, illicit, and legal psychoactive substances as SCB, SCH, extasy, amphetamine, cocaine, cannabis, and alcohol. This confusing pattern, also found in a previous study with NPS-users by Higgins et al. (Citation2021) has its implications for the treatment systems. In this context, medication is usually considered but a further, easily accessible substance; or a risky attempt at self-medication to terminate drug-induced psychotic states (Valeriani et al., Citation2015). Mothers’ benzodiazepine use in some families is a direct model for such a misuse of prescription medication.

The overall profile of this group on MMPI-2 Restructured Clinical Scales and the PSY-5 Scales has confirmed key findings on the challenging nature of NPS use. RC4 scores indicating antisocial behavior comprising “aggressiveness, antagonism, argumentativeness, tendency to lie, cheat, difficulty conforming to societal norms, acting out, substance abuse, family conflicts and poor achievement” (MMPI Info, n.d.a) were elevated with 65 persons. RC 8, Aberrant Experiences measuring hallucinations, bizarre perceptual experiences, delusional beliefs, and impaired reality testing was elevated with 43 respondents. The PSY-5 scale Disconstraint as “insufficient delay of gratification, be unreliable, rebellious, hedonistic, and acting out” (MMPI Info, n.d.b) and PSY (“poor reality testing, are suspicious, delusional and hostile”) scores were elevated in approximately half of the sample, with 35 and 36 respondents, respectively. Interestingly, while the use of classical substances, particularly the stimulant Cocaine, and LSD, a hallucinogen, was interrelated with specific problems in emotion regulation, supporting Khantzian’s claim (2011), NPS types were not related to any of the MMPI-2 scales that are informative on emotion regulation, reflecting the rapidly changing, more instable and chaotic character of NPS use. When considering all the RC scales we have used, LSD takes the lead with significant positive correlations except RC2. LSD also correlates with PSYCH. Interestingly, we could identify a significant positive correlation with SCB use and RC4, similar in strength to the relation between LSD/Heroin use and RC4. In a study using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis, Kassai et al. (Citation2017) have identified SCB use as a particular type of trauma. There is strong evidence in the professional literature that childhood trauma and antisocial behavior are related, and this may explain for our findings (Schorr et al., Citation2020).

This population’s problems in emotion regulation are salient. Elevated scores may indicate a problem that existed prior to or is parallel with substance use. More than half of the respondents had high scores on RCd and RC7. Nearly half of the sample, 36 of the 77 patients also scored high on NEGE. These scales are strongly associated with PTSD, primarily with internalizing psychopathology, though Wolf and associates (2008, p. 338) claim that „…while more strongly associated with the internalizing spectrum, (NEGE) may also play a role in externalizing disorders”. In the same study, authors found a negative correlation between SUD and RC2.

Our results are consistent with the studies connecting substance use (Hien et al., Citation2022; Roberts, Citation2021; Van den Brink, Citation2015), or more specifically, NPS use (Csák et al., Citation2020; Kassai et al., Citation2017) to psychological trauma.

6. Conclusions. Implications for therapy and research

In this study, authors examined a group that is rarely accessible for scientific research, though their problems challenge the existing medical and social services for persons with SUD. Currently, relatively little is known about NPS users’ social context, life experiences and psychopathology, and this is a barrier to providing more adequate treatment options. NPS use, likewise the use of classical substances, seems to be characterized by specific problems in emotion regulation and is related to psychological traumatization (Kassai et al., Citation2017), also supported by the results of our analysis. Though our results are tentative due to the limitations of the sample size, and to lack of a control group, and, most importantly, to the fact that NPS use is embedded in polydrug use, these users do not seem to self-medicate their emotional dysfunctions in a traditional way, choosing a specific NPS according to the problem type. These efforts are related to classical substances. Their chaotic polydrug use may render pharmacotherapy difficult or contraindicated, as users consider prescription medication just another cheap substance to be mixed with the ones they normally use. Psychotherapeutic services, as viable options in these cases, are not widespread in Hungary, and in certain regions may be available in private practice only. Female users’ underrepresentation in this sample supports the claim that women’s drug use is a specific problem, and it would demand more targeted interventions (Kaló, Citation2020). Helping parents with alcohol or substance use disorder recover, and thus protect their children from the long-term consequences of the transgenerational transfer of SUD should be made part of the solution.

From a methodological point, the strengths of this study are triangulation and controlled sampling, eliminating potentially problematic self-reports on respondents’ drug use. As for the limitations, a more homogenous sample could have resulted a clearer picture on NPS use, but this population is hard to reach and involve in a study, so we had to accept this as a barrier. The broad age range implies diverse paths and stages in the development of substance use disorder. We only included one legal substance (alcohol) and did not examine the use of nicotine or the illicit use of prescription drugs. Further, the sample comprised persons who participated in some form of a treatment. This is one reason why persons with lower levels of education and/or living in rural areas had less chances to be included in the sample. One of the methods, MMPI-2, excluded persons with less than 5th grade elementary school education. Further, estimates on parental substance use were based on respondents’ report. The Covid-19 restrictions in the country during the one year of data collection in 2020 and 2021, significantly changing the conditions for access to care, somewhat delimited sample size.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was issued by the University of Pécs, on the condition that respondents’ anonymity is ensured (PTE KK RIKEB, 2019. 05. 02.).

Patient consent statement

Respondents were informed by the first author about the study and all of them agreed to participate.

Disclosure statement

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data availability statement

The quantitative data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the library repository of the University of Pecs at https://pea.lib.pte.hu/handle/pea/34040.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdulrahim, D., & Bowden-Jones, O. (2015). Guidance on the management of acute and chronic harms of club drugs and novel psychoactive substances. NEPTUNE.

- Alves, V. L., Gonçalves, J. L., Aguiar, J., Teixeira, H. M., & Câmara, J. S. (2020). The synthetic cannabinoids phenomenon: From structure to toxicological properties. A review. Critical Reviews in Toxicology, 50(5), 359–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408444.2020.1762539

- Arbisi, P. A., Sellbom, M., & Ben-Porath, Y. S. (2008). Empirical correlates of the MMPI-2 Restructured Clinical (RC) Scales in psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment, 90(2), 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890701845146

- Archer, R. P. (2006). A perspective on the restructured clinical (RC) scale project. Journal of Personality Assessment, 87(2), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa8702_07

- Bateman, A. W., & Fonagy, P. (2019). Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice. American Psychiatric Publishing Inc.

- Butcher, J. N., Graham, J. R., Ben-Porath, Y. S., Tellegen, A., Dahlstrom, W. G., & Kaemmer, B. (2001). MMPI-2 (Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2) manual for administration, scoring, and interpretation (translated by OS Hungary Tesztfejlesztő Kft., 2009 – Revised edition). OS Hungary Tesztfejlesztő Kft.

- Csák, R., Szécsi, J., Kassai, S., Márványkövi, F., & Rácz, J. (2020). New psychoactive substance use as a survival strategy in rural marginalised communities in Hungary. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 85, 102639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.102639

- Csorba, J., Figeczki, T., Kiss, J., Medgyesi-Frank, K., & Péterfi, A. (2017). Intravénás szerhasználatból származó anyagmaradványok vizsgálata. In K. Felvinczi (Ed.), Változó képletek - Új(abb) szerek: Kihivások, mintázatok (pp. 87–103). L’Harmattan.

- Dvir, Y., Ford, J. D., Hill, M., & Frazier, J. A. (2014). Childhood maltreatment, emotional dysregulation, and psychiatric comorbidities. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 22(3), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000014

- Elekes, Z. (2014). Hungary’s neglected "alcohol problem": Alcohol drinking in a heavy consumer country. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(12), 1611–1618. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2014.913396

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. (2016). Voluntary EMQ module for monitoring use of new (and not so new) psychoactive substances (NPS) in general adult population surveys and school surveys. EMCDDA.

- Finn, S. E., &Kamphuis, J. H. (2006). The MMPI-2 Restructured Clinical (RC) Scales and restraints to innovation, or "what have they done to my song?". Journal of Personality Assessment, 87(2), 202–210. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa8702_10

- Fonagy, P., Gergely, G. Y., Jurist, E. L., & Target, M. (2002). Affect regulation. Mentalization and the development of the self. Other Press.

- Forbey, J. D., & Ben-Porath, Y. S. (2008). Empirical correlates of the MMPI-2 Restructured Clinical (RC) Scales in a nonclinical setting. Journal of Personality Assessment, 90(2), 136–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890701845161

- Graham, J. R. (2000). MMPI-2: Assessing personality and psychopathology (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Greene, R. L. (2000). The MMPI-2: An interpretive manual (2nd ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

- Hien, D. A., Fitzpatrick, S., Saavedra, L. M., Ebrahimi, C. T., Norman, S. P., Tripp, J., Ruglass, L. M., Lopez-Castro, T., Killeen, T. K., Back, S. E., & Morgan-López, A. A. (2022). What’s in a name? A data-driven method to identify optimal psychotherapy classifications to advance treatment research on co-occurring PTSD and substance use disorders. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2001191. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.2001191

- Higgins, K., O’Neill, N., O’Hara, L., Jordan, J. A., McCann, M., O’Neill, T., Clarke, M., O’Neill, T., Kelly, G., & Campbell, A. (2021). New psychoactives within polydrug use trajectories – Evidence from a mixed-method longitudinal study. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 116(9), 2454–2462. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15422

- Hungarian National Focal Point. (2020). 2020 National Report to the EMCDDA by the Reitox National Focal Point: Hungary. Reitox.

- Kaló, Z. (2020). Bevezetés a szerhasználó nők világába. L’Harmattan.

- Kaló, Z., & Felvinczi, K. (2017). Szakértői dilemmák és az ÚPSZ-használat észlelt mintázatai. In K. Felvinczi (Ed.), Változó képletek - Új(abb) szerek: Kihivások, mintázatok (pp. 103–125). L’Harmattan.

- Kaló, Z., Kassai, S., Rácz, J., & Van Hout, M. C. (2020). Synthetic cannabinoids (SCs) in metaphors: A metaphorical analysis of user experiences of synthetic cannabinoids in two countries. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18(1), 160–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9970-0

- Kassai, S., Pintér, J. N., Rácz, J., Böröndi, B., Tóth-Karikó, T., Kerekes, K., & Gyarmathy, V. A. (2017). Assessing the experience of using synthetic cannabinoids by means of interpretative phenomenological analysis. Harm Reduction Journal, 14(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-017-0138-1

- Khantzian, E. J. (1985). The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: Focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 142(11), 1259–1264. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.142.11.1259

- Khantzian, E. J. (1997). The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent application. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 4(5), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.3109/10673229709030550

- Khantzian, E. J. (2011). Addiction as a self-regulation disorder and the role of self-medication. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 108(4), 668–669. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12004

- Koski-Jännes, A. (2004). In search of a comprehensive model of addiction. In P. Rosenqvist, J. Blomqvist, A. Koski-Jännes, & L. Öjesjö (Eds.), Addiction and life course (pp. 49–67). NAD Publication 44.

- Kostiuk, L. M., & Fouts, G. T. (2002). Understanding of emotions and emotion regulation in adolescent females with conduct problems: A qualitative analysis. The Qualitative Report, 7(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2002.1985

- Martinotti, G., Lupi, M., Acciavatti, T., Cinosi, E., Santacroce, R., Signorelli, M. S., Bandini, L., Lisi, G., Quattrone, D., Ciambrone, P., Aguglia, A., Pinna, F., Calò, S., Janiri, L., & di Giannantonio, M. (2014). Novel psychoactive substances in young adults with and without psychiatric comorbidities. BioMed Research International, 2014, 815424. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/815424

- McKernan, L. C., Nash, M. R., Gottdiener, W. H., Anderson, S. E., Lambert, W. E., & Carr, E. R. (2015). Further evidence of self-medication: Personality factors influencing drug choice in substance use disorders. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 43(2), 243–275. https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2015.43.2.243

- MMPI Info. (n.d.a). Restructured Clinical (RC) Scales. https://www.mmpi-info.com/restructured-clinical-rc-scales

- MMPI Info. (n.d.b). Supplementary Scales. https://www.mmpi-info.com/supplementary-scales

- Nagulendran, A., & Jobson, L. (2020). Exploring cultural differences in the use of emotion regulation strategies in posttraumatic stress disorder. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1729033. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1729033

- Nichols, D. S. (2001). Essentials of MMPI-2 assessment. John Wiley & Sons.

- Osberg, T. M., Haseley, E. N., & Kamas, M. M. (2008). The MMPI-2 clinical scales and restructured clinical (RC) scales: Comparative psychometric properties and relative diagnostic efficiency in young adults. Journal of Personality Assessment, 90(1), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890701693801

- Rácz, J., Csák, R., Tóth, K. T., Tóth, E., Rozmán, K., & Gyarmathy, V. A. (2016). Veni, vidi, vici: The appearance and dominance of new psychoactive substances among new participants at the largest needle exchange program in Hungary between 2006 and 2014. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 158(1), 154–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.034

- Roberts, N. P. (2021). Development of expert recommendations for the treatment of PTSD with comorbid substance use disorder. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(sup1). https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1866419

- Roberts, N. P., Roberts, P. A., Jones, N., & Bisson, J. I. (2015). Psychological interventions for post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbid substance use disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 38, 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.007

- Schifano, F., Orsolini, L., Papanti, D. G., & Corkery, J. M. (2015). Novel psychoactive substances of interest for psychiatry. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 14(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20174

- Schorr, M. T., Tietbohl-Santos, B., de Oliveira, L. M., Terra, L., de Borba Telles, L. E., & Hauck, S. (2020). Association between different types of childhood trauma and parental bonding with antisocial traits in adulthood: A systematic review. Child Abuse & Neglect, 107, 104621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104621

- Sellbom, M., & Ben-Porath, Y. S. (2005). Mapping the MMPI-2 Restructured Clinical scales onto normal personality traits: Evidence of construct validity. Journal of Personality Assessment, 85(2), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa8502_10

- Sellbom, M., Ben-Porath, Y. S., Baum, L. J., Erez, E., & Gregory, C. (2008). Predictive validity of the MMPI-2 Restructured Clinical (RC) Scales in a batterers’ intervention program. Journal of Personality Assessment, 90(2), 129–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890701845153

- Sellbom, M., Graham, J. R., & Schenk, P. W. (2006). Incremental validity of the MMPI-2 Restructured Clinical (RC) scales in a private practice sample. Journal of Personality Assessment, 86(2), 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa8602_09

- Tamama, K., & Lynch, M. J. (2020). Newly emerging drugs of abuse. In M. Nader, & Y. Hurd (Eds.), Substance use disorders. From etiology to treatment (pp. 463–502). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/164_2019_260

- Tellegen, A., Ben-Porath, Y. S., McNulty, J. L., Arbisi, P. A., Graham, J. R., & Kaemmer, B. (2003). MMPI-2 restructured clinical (RC) scales: Development, validation, and interpretation. University of Minnesota Press.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2013). The challenge of new psychoactive substances. UNODC.

- Valeriani, G., Corazza, O., Bersani, F. S., Melcore, C., Metastasio, A., Bersani, G., & Schifano, F. (2015). Olanzapine as the ideal "trip terminator"? Analysis of online reports relating to antipsychotics’ use and misuse following occurrence of novel psychoactive substance-related psychotic symptoms. Human Psychopharmacology, 30(4), 249–254. https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.2431

- Van den Brink, W. (2015). Substance use disorders, trauma, and PTSD. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v6.27632

- Van Hout, M. C., Benschop, A., Bujalski, M., Dąbrowska, K., Demetrovics, Z., Felvinczi, K., Hearne, E., Henriques, S., Kaló, Z., Kamphausen, G., Korf, D., Silva, J. P., Wieczorek, Ł., & Werse, B. (2018). Health and social problems associated with recent Novel Psychoactive Substance (NPS) use amongst marginalised, nightlife and online users in six European countries. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 16(2), 480–495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9824-1

- Werb, D., Richardson, C., Buxton, J., Shoveller, J., Wood, E., & Kerr, T. (2015). Development of a brief substance use sensation seeking scale: Validation and prediction of injection-related behaviors. AIDS and Behavior, 19(2), 352–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0875-z

- Wolf, E. J., Miller, M. W., Orazem, R. J., Weierich, M. R., Castillo, D. T., Milford, J., Kaloupek, D. G., & Keane, T. M. (2008). The MMPI-2 restructured clinical scales in the assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid disorders. Psychological Assessment, 20(4), 327–340. https://doi.org/10.1037/a001