Abstract

Background

A home exercise program (HEP) is integral in the management of rotator cuff related shoulder pain (RCRSP). There are many methods of measuring HEP adherence and many possible interventions to promote HEP adherence. Understanding the adherence rates to HEP and the strategies used to promote HEP adherence is important in order to interpret the existing evidence for the use of HEP in the management of RCRSP.

Objectives

To report and synthesize home exercise adherence and strategies to promote home exercise adherence in order to understand the limitations of the current evidence base and make recommendations for clinical practice and future research investigating HEPs in the management of RCRSP.

Methods

An electronic search of EMBASE, MEDLINE, PubMed, CINAHL, AMED, and CENTRAL was undertaken. Methodological quality was assessed using the Cochrane RoB 2.0, and BC techniques were coded in accordance with the BC technique taxonomy (version 1).

Results

Seventeen RCTs were retrieved. Forty-seven percent described a formal method of measuring HEP adherence and 29% described adherence rates. The included studies described between three and seventeen BC techniques and the mean number of BC techniques per study was 5.8. Twelve percent of the studies described offering patients an explanation of how the exercise program might help their symptoms resolve.

Conclusions

Poor reporting of adherence and the underutilisation of BC interventions to promote HEP adherence was prevalent. Recommendations for clinicians and researchers include more widespread use and definitive reporting of BC techniques to promote adherence, and the use of objective, patient self-reported, and clinician-assessed measures of adherence when prescribing HEPs.

Introduction

Advice, education and exercise are the main management strategies for rotator cuff related shoulder pain (RCRSP) (Citation1, Citation2), and exercise may either be supervised in the clinic, given as a home exercise program (HEP), or both. HEPs promote self-management and may facilitate more regular exercise participation, for longer durations, which may translate to better outcomes. The effectiveness of HEPs are dependent upon patient adherence (Citation3, Citation4), however there are significant challenges for patients in adopting HEPs, and for clinicians in measuring and improving HEP adherence.

The problem of adherence

Adherence to physiotherapist-prescribed HEPs has been shown to be an important predictor of treatment outcome (Citation3, Citation4); despite this, research reports that 50–70% of patients are either non-adherent or partially adherent to their HEP (Citation4, Citation5). Poor treatment adherence is a concern across many healthcare disciplines and not just physiotherapy (Citation6). Non-adherence to medical interventions results in poorer outcomes, avoidable morbidity and wasted resources (Citation7).

There is a strong evidence base reporting the efficacy of therapeutic exercise in the management of RCRSP (Citation8), and a growing number of systematic reviews recommend its use (Citation9, Citation10). It is difficult, however, to make recommendations regarding individual care, based on the evidence from systematic reviews, if measures of adherence are not assimilated into the risk of bias evaluation. Many of the systematic reviews reporting on the use of exercise in the management of RCRSP have used risk of bias tools that do not incorporate a measure of ‘adherence to the intervention’ as part of the risk of bias evaluation. For example, Kelly et al. (Citation11), Bury et al. (Citation12), Haik et al. (Citation11) used the PEDro tool; Littlewood et al. (Citation13), Dong et al. (Citation14), Steuri et al. (Citation9), Gutierrez-Espinoza et al. (Citation15) used the original Cochrane tool, and Abdulla et al. (Citation16) used the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network criteria. These tools evaluate attrition (loss to follow-up) but not adherence to the intervention. Knowing the effect of assigning an individual to an intervention (the intention-to-treat effect) will aid decision making at a population level, but to inform individual decision-making, it is important to know how well the intervention was adopted (Citation17). The ‘effect of adhering’ to the intervention is most useful to help clinicians inform individual care decisions. In order to understand how effective an intervention is at reducing pain and disability, it is important to understand how well it has been adopted.

Promoting exercise adherence

Health behavior has been defined as, ‘any activity undertaken for the purpose of preventing or detecting disease or for improving health and wellbeing’ (Citation18). Adopting a home exercise program to promote recovery from shoulder pain and disability, therefore, can be considered a health behavior and strategies to promote adherence may be informed by behavior change theory. Guidelines for the development of complex interventions recommend that interventions ’should be informed by theory’ (Citation19, p.2). Theories ‘are used to understand phenomena, guide observations and develop intervention’ (Citation20, p.359). Without the use of theory in the development of intervention ‘outcomes would be largely driven by chance rather than method’ (Citation21). Despite this, the practice of developing educational and behavior change interventions without the use of an explicit theoretical framework seems to be widespread throughout the healthcare literature (Citation22).

Behavior change technique taxonomy (v1)

The Behavior Change (BC) Technique Taxonomy (Version 1) was developed to firstly, promote clearer description and replication of BC interventions, and secondly to use this taxonomy to better understand which BC techniques are more effective at influencing behavior (Citation23). The BC Technique Taxonomy (v1) describes 93 consensually agreed and distinct BC techniques that may be used to facilitate BC (Citation23). According to the taxonomy a BC technique is ‘an irreducible component of an intervention designed to alter or redirect causal processes that regulate behavior’ (Citation23, p.82). BC interventions are composed of any number of carefully selected BC techniques that target the desired behavior. Each BC technique is thoroughly described within the taxonomy and this description enables researchers to identify which BC techniques were used in a BC intervention.

The evidence to support the use of BC techniques for enhancing exercise adherence is growing. Meade et al. (Citation24) reports that the utilization of BC techniques improved adherence to prescribed exercise in individuals with persistent musculoskeletal pain. They reported that studies employing more than seven BC techniques, in addition to those included in the control group, were most effective at improving adherence. Willett et al. (Citation25) reported that the BC techniques; 'behavioral contract', 'non-specific reward', 'patient-led goal setting' (behavior), 'self-monitoring of behavior', and 'social support (unspecified) demonstrated the highest effectiveness ratios in promoting physical activity adherence in individuals with lower limb osteoarthritis.

By understanding what BC techniques have and have not been used in clinical trials for RCRSP, it may be possible to develop more comprehensive BC interventions, which may promote greater HEP adherence and improve outcomes.

Aims and objectives

Understanding home exercise adherence is important in order to understand and interpret the results of published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the use of exercise in the management of RCRSP. The aim of this systematic review is to report and synthesize home exercise adherence and strategies to promote home exercise adherence in order to understand the limitations of the current evidence base and make recommendations for clinical practice and future research investigating home exercise in the management of RCRSP.

Objectives

To describe the recorded and reported adherence rates to HEPs in RCTs.

To describe and synthesis the strategies to promote HEP adherence in terms of BC techniques using the BC Technique Taxonomy (V1) used to promote HEP adherence in the management of RCRSP.

Provide recommendations for clinicians and researchers to improve strategies to record exercise adherence, and promote adherence through the use of BC interventions.

Methods

Protocol and registration

The objectives and methodology were specified in advance and registered on the PROSPERO database: PROSPERO 2019 CRD42019121358. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=121358

Information sources

Studies were identified by searching six electronic databases: EMBASE, MEDLINE, PubMed, CINAHL, AMED, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). Searches were restricted to publications in English language. The original search was restricted to trials published between, January 1st 1990 and October 31st 2018. An additional search was performed on 7th January 2020 to include publications up to that date. Free text and thesaurus searches were performed in all databases where possible. In addition, the reference section of relevant systematic reviews (Citation9–11, Citation13, Citation14, Citation16, Citation26–30) and included RCTs were searched off-line for additional trials.

Search strategy

The following terms were used: rotator cuff related shoulder pain, RCRSP, subacromial, SAPS, rotator cuff, shoulder impingement syndrome, rotator cuff injuries, tendon injuries, painful arc, exercise, strength, training, loading, stretch, endurance, physical, muscle, motor, scapular, proprioceptive, therap*, remedial, randomised OR randomized controlled trial or RCT. MeSH descriptors and Boolean operators were used to refine the search. The detailed search strategy (EMBASE) is included in Appendix A.

Eligibility criteria

Study design

Published, peer-reviewed RCTs with a minimum mean number of 30 participants in each arm. Pilot searching identified many very small RCTs from which it was not possible to draw clinically or statistically meaningful conclusions due to the insufficient sample size. As such only published, peer-reviewed RCTs with a minimum sample size of 30 were selected. A sample size of 30 or more was chosen as this has been described as the sample size at which independent random variables become normally distributed (central limit theorem), allowing probabilistic and statistical methods that work for normal distributions to be applied to the data (Citation31) and, as a result, is often quoted as a generic minimum sample size for RCTs (Citation32). All other study designs were excluded.

Participants

Adults aged over 18-years with a presentation consistent with RCRSP of more than 3 months duration. RCTs that included patients with a non-specific diagnosis, clinically identifiable massive full thickness rotator cuff tears, adhesive capsulitis, calcific tendonitis, osteoarthritis, or who had a history of fracture or dislocation, infection, neoplasm, and inflammatory disorders were excluded.

Interventions

The primary intervention of interest was HEP for people with RCRSP. Only studies delivering therapeutic HEPs were included in the analysis. Therapeutic exercise was defined by Abdulla et al. (Citation16, p.2) as; ‘any series of movements with the aim of training or developing the body or as physical training to promote good physical health’. HEP may include resisted movements of the shoulder, passive movements, assisted or active assisted, proprioceptive exercise, stretching and aerobic exercise. Studies were included if one intervention arm fitted these criteria, even if the comparator arm included passive or surgical interventions. Studies where a HEP was delivered as part of a multimodal treatment package were also included.

Condition being studied – rotator cuff related shoulder pain (RCRSP)

The term RCRSP was introduced by Lewis (Citation33) as an umbrella term to include conditions previously referred to as rotator cuff tendinopathy, shoulder impingement and subacromial pain syndrome. When other causes are considered unlikely, RCRSP typically involves the experience of pain and movement impairment during elevation and external rotation (Citation33). Studies were excluded if they described a population with a non-specific diagnosis such as ‘shoulder pain’.

Outcome

The outcome for BC interventions is the degree to which the behaviour is adopted. This review is not intending to describe functional outcome in terms of pain and disability. For this reason the outcome described in this review is the level of adherence to the prescribed HEP.

Study selection

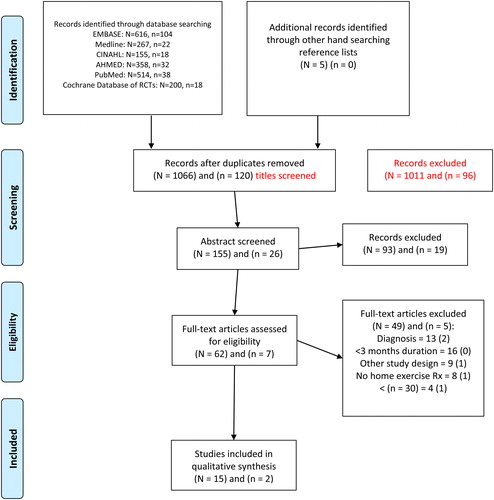

Titles and abstracts were retrieved using the search strategy, and duplicates removed. The titles and abstract were reviewed by two reviewers (KH and CM) and included for full text review based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. At each stage disagreement between the reviewers was resolved through consensus. A third reviewer (CR) was available if discussion was insufficient to reconcile any uncertainties. The full text of the remaining papers was retrieved and reviewed by the same two reviewers, who independently selected trials for inclusion. Reasons for exclusion at each stage were recorded (see PRISMA flow diagram, ).

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram (from Moher et al. (Citation34)).

(N = original search 31st October 2018, n = second search 7th January 2020)

Data collection process

A standardized, pre-piloted form was used to extract data relating to study characteristics from the included studies. Data were extracted independently by two researchers (KH and AG) and agreement was reached through consensus. A third author was available if consensus could not be reached (CR). Study characteristics relating to HEP participation and the measurement of HEP adherence were extracted from the manuscript (). Methods used for measuring adherence, reported level of adherence, how authors defined adherence or compliance and any target adherence rate were recorded ().

Table 1. Study characteristics for home exercise participation and the measures of adherence.

Data extraction and coding of BC techniques were performed in accordance with the BC Technique Taxonomy (Version 1) methodology training (http://www.bct-taxonomy.com) (Citation23). This formal online training was completed by two authors (KH and AG) in order to standardize the data extraction and coding of BC interventions. The text describing strategies used within the RCTs to promote adherence to HEP was extracted independently by 2 authors (KH and AG), from the intervention descriptions in all published material relating to the study, including protocols, supplementary files and appendices. All strategies used by the study authors in an effort to improve adherence to the HEPs were coded. BC techniques were coded when there was clear evidence of their inclusion in the description of interventions. For a BC technique to be coded as present both reviewers needed to agree it was present in the intervention or the control arm or both.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Two reviewers (KH and CM) independently assessed the risk of bias of each included study using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (RoB 2.0). This evaluation was conducted according to the RoB 2.0 handbook for RCTs (Citation52). In the RoB 2.0 tool (Citation17) there are two options for the evaluation of bias due to deviations from the intended interventions: reviewers may evaluate the effect of adhering to the interventions as specified in the trial protocol (‘per protocol effect’) or the effect of assignment to the interventions at baseline, regardless of whether the interventions are received or adhered (‘as assigned effect’). The ‘per protocol effect’, of adhering to the interventions as described in the protocol, is most appropriate to inform an individual care decision for patients and clinicians (Citation17). Evaluation of risk of bias within this domain provides an understanding of the measurement and reporting of adherence to HEPs in clinical trials of physiotherapy interventions (Citation52).

Strategy for data synthesis

The following data was synthesized from the included studies and presented qualitatively, and with descriptive statistics:

Parameters used to define adherence, methods used to measure HEP adherence and reported adherence rates.

Interventions used to promote HEP adherence defined in terms of the BC Technique Taxonomy (Version 1) (Citation23).

Results

Study selection

A total of 2110 studies were identified through the search strategies in October 2018; after duplicates were removed, 1066 remained. Following title review, 1011 publications were excluded. One hundred and fifty five abstracts were reviewed, resulting in the review of 62 full text publications. Fifteen of these studies met all inclusion criteria (Citation35–38, Citation41–51). An updated search using the same strategy and databases was performed on 7th January 2020. This search identified 232 studies; after duplicates were removed 120 studies remained. Ninety-four were excluded at title review, and 26 abstracts were reviewed, resulting in the review of seven full text publications. Two additional papers were identified for inclusion (Citation39, Citation40). The total number of papers included in the full review was 17. Full summary of the stages of study selection are detailed in , PRISMA flow diagram. The percentage agreement and Kappa values between reviewers for study inclusion at each stage, and the RoB evaluation is detailed in .

Table 2. Agreement between reviewers for inclusion and risk of bias evaluation.

Risk of bias within studies

The RoB 2.0 evaluation for each study is represented in . Of the 17 studies evaluated, 2 (12%) were assessed as having a low RoB (Citation35, Citation44). Ten studies (58%) (Citation36, Citation38, Citation40, Citation41, Citation45, Citation46, Citation48–51) were deemed to have a high RoB in two or more domains (see ). The most common domain ascribed a high risk of bias was, ‘Risk of bias due to deviations from intended interventions (effect of adhering to interventions)’, and was due to poor adherence or unknown adherence. Twelve (71%) of the 17 studies did not mention adherence rates to prescribed HEP, despite HEP comprising the major component of the exercise-based intervention (Citation36–41, Citation45, Citation46, Citation48–50). Two (12%) studies reported completion rates for measures of adherence (exercise diaries) of <40% (Citation42, Citation47) and two (12%) study reported adherence rates of >80% (Citation35, Citation43) (see ).

Table 3. Risk of Bias (RoB) 2.0 tabulated results for each included study and each domain.

The second most common cause of bias was in the domain ‘measurement of the outcome’, where nine (53%) studies were classified as high risk of bias (Citation36, Citation38, Citation41, Citation45, Citation46, Citation48–51). The main reason for classification of high RoB in these studies was participants’ knowledge of the intervention group and the use of patient reported outcome measures (PROMs).

Describing adherence to the home exercise programs

The tabulated results of the evaluation of adherence in the included studies are described in . Of the 17 studies, eight (47%) described a formal method of measuring adherence; in seven studies (41%) this was an exercise diary (Citation35, Citation36, Citation42–44, Citation47, Citation48) and in one study it was a weekly review of adherence with their physiotherapist (Citation40). Of the eight studies reporting that adherence was measured, five (29%) studies described the reported adherence rates to the prescribed HEP (Citation35, Citation42–44, Citation47). Four (24%) of the studies that measured adherence defined which parameters of adherence were measured. These parameters were; ‘completed home exercise sessions’ (Citation35), ‘days missed’ (Citation43), ‘number of sets and repetitions per set for every training session’ (Citation44) and ‘percentage adherent’ (Citation47).

Two (12%) studies described a target adherence; Holmgren et al. (Citation43) described <18% of days missed (unclear if this was based on post hoc analysis) and Ingwerson et al. (Citation44) more than 80% (pre-specified in the protocol). Completion rate of the exercise diary was reported in 4 (24%) studies and showed considerable variability. Completion rates ranged from 91% of participants (Citation35), to 88-89% (Citation43), 30-35% (Citation42), and 29% (Citation47).

In addition to diary completion rates, adherence to the exercise program was described in three of these studies: Bennell et al. (Citation35) reported 82% adherence (group average), Holmgren et al. (Citation43) reported 88 and 89% adherence for the two arms, and Littlewood et al. (Citation47) reported 20-100% adherence (individual range of adherence in the ‘self managed’ arm of the trial only). In addition, Ingwerson et al. (Citation44) described 57% and 61% (two arms) of patients achieving the target adherence of 80%. A sensitivity analysis based on target adherence was performed in 1 study (Citation44).

There was no report of adherence rates, target adherence, completion of adherence measures, or evidence of adherence to a HEP having being recorded in any of the five studies comparing surgical intervention with exercise (Citation36, Citation41, Citation45, Citation46, Citation50).

Describing the use of behavior change techniques

There were 17 different BC techniques described across all publications, trial registrations, protocols, appendices and supplementary data of the included studies. The details of extracted BC techniques can be found in and and Appendix B. The included studies described between three and 15 BC techniques; the mean number per study was 5.8. The most commonly used BC techniques were ‘instruction on how to perform the behavior’ (16 studies, 94%) (Citation35–39, Citation41–51), ‘demonstration of the behavior’ (15 studies, 88%) (Citation35–39, Citation41–49, Citation51), ‘behavioral practice and rehearsal’ (15 studies, 88%) (Citation35–39, Citation41–49, Citation51), and ‘goal setting (behavior)’ (14 studies, 88%) (Citation35, Citation36, Citation38–40, Citation42–45, Citation47–51). The number of BC techniques used in each study varied greatly, for example Littlewood et al. (Citation47) described the use of 15 BC techniques, Bennell et al. (Citation35) described 9 BC techniques, and five studies described using three BC techniques (Citation37, Citation40, Citation41, Citation46, Citation50). Only one study reported a theoretical framework underpinning the design of adherence interventions (Citation47). A full description of the BC technique coding for each study is detailed in Appendix B.

Table 4. Behavior change techniques used in each study.

Table 5. Frequency of use of behavior change techniques.

Discussion

The results of this review will be discussed with a particular focus on the importance of understanding the impact of adherence on research findings, and to what extent BC interventions have been used to promote HEP adherence in the existing RCTs. Recommendations for clinicians and researchers will be made in an attempt to improve strategies to measure and record exercise adherence, and promote adherence through the use of BC interventions, to ultimately improve clinical outcomes ().

Table 6. Recommendations for Clinicians and researchers.

Risk of bias analysis

The most common cause of bias in the included studies was due to deviation from intended interventions (effect of adhering to interventions), 14 (82%) of included studies were deemed to be at high risk of bias in this domain, either due to failure to report adherence (12 studies, 71%) (36–Citation41, Citation45, Citation46, Citation48–50) or the reporting of low completion rates of adherence diaries (2 studies, 12%) (Citation42, Citation47).

Only five (29%) studies reported adherence rates to their HEPs. Of these Littlewood et al. (Citation47) only recorded adherence data in one arm of the study and only 29% of diaries were completed in this arm. Heron et al. (Citation42) reported diary completion rates of 30-35%. Diary completion and exercise adherence, however, are not the same, it is not possible to comment on adherence in these studies if 65-71% of the data is missing. Only two studies (12%) provided robust adherence data: Holmgren et a. (Citation43) reported 88-89% diary completion with 86-87% adherence; and Bennell et al. (Citation35) reported 93% diary completion with 82% adherence. Without robust measurement and reporting of exercise adherence it is not possible for researchers to retrospectively evaluate the impact of BC interventions on exercise adherence.

By reporting only functional outcomes, the effectiveness of a BC intervention is confounded with the effectiveness of the exercise program; for example a less effective exercise program with greater adherence, or a more effective exercise program with lower adherence may achieve the same clinical outcomes. BC interventions target a behavior (exercise adherence); the effectiveness of a BC intervention, therefore, should be measured with exercise adherence outcome rather than a functional outcome. Without reporting adherence, it is not possible to know which of these effects is being observed in 14/17 (84%) of the included studies.

Eight (47%) studies reported using a formal measure of exercise adherence, and an exercise diary was the only method used in seven (41%) of these studies (Citation35, Citation36, Citation42–44, Citation47, Citation48). A self-reported, subjective measure of adherence, such as an exercise diary, is likely to over- or under-estimate the patient’s true adherence (Citation63). In an attempt to increase the validity of measuring exercise adherence, WHO (Citation63) recommended, ‘a multi-method approach combining self-reporting and objective measures’. There are many patient and clinician reported measures of exercise adherence, such as the Hopkins rehabilitation engagement rating scale (Citation64) or the exercise adherence rating scale (Citation65). The psychometric properties of these outcome measures are unknown and a valid and reliable measurement tool of exercise adherence is still lacking. Recent systematic reviews evaluating measures of adherence with exercise have concluded that, ‘current measures of exercise adherence for musculoskeletal populations are of poor quality’ (Citation66, p.426). Bollen et al. (Citation67, p.3) stated ‘this is an absurd and messy situation for appraising the benefits of unsupervised home-based exercise rehabilitation’. Until measures for recording adherence exist that have proven validity and reliability, it is recommended that researchers triangulate data from a combination of objective, patient self-reported and clinician-assessed measures of adherence in RCTs when recording and describing HEP adherence (). It is recommended that clinicians consider patient self-reported and clinician-assessed measures of HEP adherence in addition to exercise diaries when assessing HEP adherence in the clinic.

All seven studies comparing HEP interventions with more invasive forms of treatment, such as surgery, prolotherapy injections or platelet rich plasma (PRP) injections, failed to report adherence to the exercise arm (Citation36, Citation41, Citation45, Citation46, Citation49–51). The authors were able to accurately describe adherence with the surgical treatment, and define exactly the number of PRP or prolotherapy injections received by patients, but did not report any aspect of adherence with the exercise component of treatment, or describe any attempt to measure and record adherence to exercise. The direction of this bias favors the surgical comparator. It is strongly recommended that when researchers conduct RCTs comparing exercise interventions with more invasive, costlier and less safe interventions, researchers record and report the level of adherence in both arms of the study with equal rigor (). It is not possible to understand the effectiveness of an exercise intervention if it is not known how well it was implemented or adopted. Interpreting the outcomes of these seven studies should reflect this lack of clarity regarding adherence to the exercise interventions.

Although there are many parameters or aspects of exercise adherence that may be measured, exercise frequency was the only parameter used to measure exercise adherence in the 17 included studies. Following their systematic review on measures of exercise adherence, McClean et al. (Citation66, p.436) concluded that, ‘the conceptual underpinnings of what should be assessed, by whom, when and in what context are poorly considered’. Frost et al. (Citation68, p.1242) have defined HEP adherence as, ‘the extent to which individuals undertake prescribed behavior accurately and at the agreed frequency, intensity and duration’. Bailey et al. (Citation69) identified 8 parameters of exercise adherence; number of days exercised, completed sessions, number of completed sets, days missed, intensity, duration, accuracy; in addition, ‘achieving target sensation’, such as fatigue, or pain could also be measured. It is recommended that researchers specify explicitly in their protocol the precise parameters of the prescribed exercise in terms of the dose, but also the target sensation (pain or fatigue), and that these parameters are reflected in the measures of adherence (). The specific parameters of adherence to a HEP need careful consideration in the planning and application of adherence monitoring, not just an acknowledgement that exercises were performed to some extent. It is recommended that clinicians consider not only the dose of exercise but also what their patients experience in terms of pain and fatigue.

Only one of the 17 studies (Citation44) pre-defined a ‘target adherence’, which was 80% of the number of sets and repetitions performed during every training session. There seems to be no consensus within the literature as to what level of adherence is acceptable or desirable. It is recommended that future studies predefine a ‘target adherence’ and perform adherence subgroup sensitivity analysis which may provide an understanding of what constitutes ‘desirable adherence’, based on more scientific principles than opinion ().

Behavior change techniques

The mean number of BC techniques used in the 17 included studies was 5.8, and a total of 17 BC techniques were used to promote HEP adherence across all studies ( and ). Michie et al. (Citation23) describes 93 BC techniques in their BC taxonomy, therefore the mean number of BC techniques used in the included studies constitutes 6% of the total number of techniques described in the taxonomy. Although not all of the techniques may be appropriate for promoting adherence to a HEP, the low mean number reported in this systematic review suggests that BC techniques are being under-utilized in promoting HEP adherence in the included studies. The most used BC techniques in the included studies were implemented in order to teach patients how to perform their HEPs. The three most frequently coded BC techniques were; ‘instruction on how to perform the behavior’, ‘demonstration of the behavior’ and ‘behavioral practice and rehearsal’. These three BC techniques comprised 46% (46 of 99) of all BC techniques described across all 17 studies.

It was surprising to see the underutilization of many BC techniques that seem well placed to promote adherence to HEPs. For example, ‘Information about Health Consequences’ was only reported in 2 studies (12%) (Citation44, Citation47). Therefore, only 12% of the studies described offering patients an explanation of how the exercise program might help their symptoms resolve. It must be a minimum requirement that patients have an explanation for the potentially beneficial effects of performing the HEP. It is recommended that clinicians and researchers carefully consider the content of the educational programs that they deliver. By providing information about the ‘consequences’ of performing exercise, the educational interventions may better target the desired behaviour; home exercise adherence. The educational content may come from RCTs reporting the effectiveness of exercise interventions, or from mechanistic studies reporting how exercise may cause a reduction in pain and disability.

Only one study (6%) described the use of a theoretical framework to develop interventions to promote HEP adherence (Citation47). Using theoretical models that predict behaviour to develop BC interventions, may help researchers implement more robust interventions and promote clarity and transparency for those that follow (Citation20).

The utilization of BC techniques in the prescription of exercise has been described previously. Emilson et al. (Citation70) evaluated primary care physiotherapists’ use of BC techniques with patients reporting musculoskeletal pain. Through the analysis of video recordings from the clinical interactions of 12 physiotherapists, they identified seven BC techniques that were used to facilitate physical activity. The authors suggest that this low utilization may be due to limited experience and knowledge of BC techniques (Citation70). In a systematic review of experimental and observational studies promoting physical activity, Kunstler et al. (Citation71) described the average use of 7.3 BC techniques per study. These finding are consistent with the mean number of BC techniques (5.8 per study) identified in the 17 studies included in this review.

Willett et al. (Citation25) reported that the BC techniques; 'behavioral contract', 'non-specific reward', ‘goal setting' (behavior), 'self-monitoring of behavior', and 'social support (unspecified) resulted in the highest effectiveness ratios in promoting physical activity adherence. None of the included studies in this systematic review utilized ‘behavioural-contract’ or ‘non-specific reward’ to promote adherence, and ‘social support (unspecified)’ was only described in two (12%) studies. It is recommended that clinicians and researchers understand the range of BC techniques that may be employed to promote adherence to home exercise, and understand how to select and deliver these interventions in clinical practice and research settings (Citation23). Only when robust measures and acceptable levels of adherence have been achieved will it be possible to investigate the effectiveness of different exercise strategies on clinical outcomes of RCRSP.

Strengths and limitations

This review described clear inclusion and exclusion criteria that limited the review to larger RCTs (n = 30) that recruited participants with a minimum duration of symptoms of three months. Acute symptoms commonly undergo spontaneous resolution irrespective of the intervention; excluding participants that have a high chance of spontaneous recovery (acute symptoms) is a feature of more robust study design (Citation72). Physiotherapy trials comparing two interventions commonly describe small effect size (Citation72) and high variance in the primary outcome measure. As a result studies with small sample size are less likely to generate statistically or clinically meaningful results. These inclusion criteria were chosen in an attempt to include and describe the findings of RCTs with more robust design that are more likely to generate clinically and statistically meaningful conclusions.

Risk of bias was assessed using a tool for the evaluation of experimental bias (Cochrane RoB 2.0), this tool incorporates ‘adherence to the intervention’ as part of the risk of bias evaluation. Evaluation of the BC techniques was performed using a standardized methodology and both coders completed standardized online training for coding BC techniques using BC technique taxonomy (version 1). Authors were not contacted to clarify information relating to the measurement of exercise adherence or in the use of BC interventions, because the aim of this systematic review was to evaluate the ‘reporting’ of HEP adherence and the ‘reporting’ of interventions to promote adherence with HEP.

It is possible that authors of the included studies considered aspects of BC interventions implicit within the role of physiotherapy. Authors are not expected to describe every aspect of the interaction between clinicians and patients; however, improved reporting of these aspects of care is important in order to better understand how to promote exercise adherence and more accurately determine the effectiveness of home exercise in the management of RCRSP.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that there is a great deal of variation in the utilization of BC techniques to promote adherence to HEPs in RCTs of RCRSP. The mean number of BC techniques employed in the studies is low and may be due to limited experience and knowledge of BC techniques, or poor reporting of these interventions. Many authors either fail to report HEP adherence, or report poor or unknown adherence. Understanding HEP adherence is important in order to determine the efficacy of HEPs. Developing valid and reliable outcome measures of exercise adherence is acknowledged as a major challenge, but also a major opportunity for the physiotherapy profession. Utilizing BC interventions in combination with HEPs may provide an opportunity to improve HEP adherence and clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library. We thank Sally Reynolds (Western Sussex Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust) for her technical help and support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kevin Hall

Kevin Hall (MSc, MACP, NIHR Academy Member) is an advanced physiotherapy practitioner at Western Sussex Hospitals NHS Trust and a National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Academy Member. This research is part of a larger body of work completed as part of a NIHR Clinical Doctoral Research Fellowship. This works includes a randomized controlled clinical pilot trial investigating the role of posterior shoulder tightness in shoulder pain and disability in patients with rotator cuff related shoulder pain. Kevin’s main areas of research interest are rotator cuff related shoulder pain, exercise rehabilitation, implementing behaviour change theory and promoting adherence and concordance. Kevin’s publications include book chapters, peer reviewed articles, and he has presented his work at national and international conferences.

Anthony Grinstead

Anthony Grinstead (MCSP, MSc, BSc (hons)) has been working as an NHS physiotherapist since 2010. He currently works in Musculoskeletal outpatients and as an advanced physiotherapy practitioner in a spinal clinic and an emergency department. Anthony is due to start work as a First Contact Practitioner in January 2020. He also works privately with a particular interest in running related injuries, working with a lot of local runners and triathletes. Prior to the current systematic review Anthony has previous experience as a treating physiotherapist for a feasibility study on the treatment of posterior shoulder tightness, which has provided insights into clinical research.

Jeremy S. Lewis

Jeremy S. Lewis (PhD FCSP) is a Consultant Physiotherapist and Professor of Musculoskeletal Research (University of Hertfordshire, UK). Born in New Zealand & trained in Australia, he now works in the UK National Health Service. He has been awarded a Fellowship of the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. He assesses & treats people with complex shoulder problems. Jeremy has also trained as an MSK sonographer (Postgraduate Certificate in Diagnostic Imaging-Ultrasound, University of Leeds, UK), & performs ultrasound guided shoulder injections as part of the rehabilitation process if required and appropriate. He also has completed; MSc (Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy), & Postgraduate Diplomas in; Manipulative Physiotherapy (Melbourne), Sports Physiotherapy (Curtin), & Biomechanics (Scotland), as well as MSc studies in injection therapy for soft tissues & joints. He has also qualified as an Independent (non-medical) Prescriber. His main areas of research interest are rotator cuff related shoulder pain, frozen shoulder, injection therapy, & exercise therapy. He also writes about reframing our care for people with non-traumatic musculoskeletal pain & the medicalisation of ‘normality’ in musculoskeletal practice. In addition to his own research he supervises PhD & MSc students. Jeremy was a co-editor & author for Grieve’s Modern Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy (4th ed).

Chris Mercer

Chris Mercer is a Consultant physiotherapist based at Western Sussex Hospitals Trust on the South Coast of England. He has a particular interest in Advanced Practice roles and serious pathology of the spine, particularly Cauda Equina Syndrome. He is current co-chair of the National Physiotherapy Consultant network, and Chair of the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy Education Awards Panel. He is past Chair of the Musculoskeletal Association of Chartered Physiotherapists and has recently completed a secondment role with NHSE looking at Advanced Practice roles for Allied Health Professionals in primary Care.

Ann Moore

Emeritus Professor Ann Moore (CBE, PhD, Grad.Dip.Phys, MCSP, FCSP, MACP, FMACP, Cert.Ed, Dip.TP, FHEA.DSc Honorary) is a Professor Emerita of Physiotherapy at the University of Brighton. She was awarded a professorship in 1998. From 1998 to her retirement from the UOB in 2015, Ann led and managed the Clinical Research Centre for Health Professions (1998-2013) and then the Centre for Health Research (2013 – 2015). She has specialised in Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy. Ann’s teaching and research interests have focused largely on Non Specific Low Back Pain and her research approaches have included clinical trials, Laboratory based studies, qualitative research and more latterly Art and Health research approaches. Ann has published widely in her field with 7 books, 10 book chapters, 90 Peer reviewed articles, and has made over 200 keynote and invited addresses. Ann was Director of the Council for Allied Health Professions Research (CAHPR) from 2014 -2019 and previously Director of the National Physiotherapy Research Network from 2004 to 2012 and then the Allied Health Professions Research Network from 2012 to 2014) all focused on increasing research capacity in AHPs in the UK. Ann is also Editor in Chief of Musculoskeletal Science and Practice an International Journal of Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy previously Manual Therapy Journal (1995 to date).

Colette Ridehalgh

Dr Colette Ridehalgh is a Principle Physiotherapy Lecturer at the University of Brighton. She qualified in 1992 and has worked in a number of settings both within the NHS, private practice and University. She has a special interest in managing people with nerve related musculoskeletal pain such as sciatica, carpal tunnel syndrome and neck/arm pain. She currently teaches Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy to undergraduate and postgraduate students. She has an MSc in Manipulative Physiotherapy and is a member of the Musculoskeletal association of Chartered Physiotherapists (MACP). She completed her PhD in 2014 exploring Straight Leg Raise treatment for individuals with spinally referred leg pain. Since then she has continued her research in the assessment and management of people with nerve related musculoskeletal disorders. She supervises research students from BSc (Hons) through to PhD. Colette has published widely in her field including book chapters, Peer reviewed articles, and presenting her work at national and international conferences. Colette regularly reviews articles and abstracts for scientific journals and national and international conferences. She is currently Research Officer for the MACP.

References

- Doiron-Cadrin P, Lafrance S, Saulnier M, et al. Shoulder rotator cuff disorders: A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines and semantic analyses of recommendations. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101(7):1233–1242.

- Hopman K, Krahe L, Lukersmith S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of rotator cuff syndrome in the workplace. Port Macquarie (Australia): University of New South Wales; 2013; p. 80.

- Pisters MF, Veenhof C, de Bakker DH, et al. Behavioural graded activity results in better exercise adherence and more physical activity than usual care in people with osteoarthritis: a cluster-randomised trial. J Physiother. 2010;56(1):41–47.

- Beinart NA, Goodchild CE, Weinman JA, et al. Individual and intervention-related factors associated with adherence to home exercise in chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J. 2013;13(12):1940–1950.

- Bassett SF. The assessment of patient adherence to physiotherapy rehabilitation. New Zealand J Physiother. 2003;31:60–66.

- McLean SM, Burton M, Bradley L, et al. Interventions for enhancing adherence with physiotherapy: a systematic review. Manual Ther. 2010;15(6):514–521.

- DiMatteo MR, Giordani PJ, Lepper HS, et al. Patient adherence and medical treatment outcomes: a meta-analysis. Medical Care. 2002;40(9):794–811.

- Pieters L, Lewis J, Kuppens K, et al. An update of systematic reviews examining the effectiveness of conservative physical therapy interventions for subacromial shoulder pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020;50(3):131–141. doi:

- Steuri R, Sattelmayer M, Elsig S, et al. Effectiveness of conservative interventions including exercise, manual therapy and medical management in adults with shoulder impingement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(18):1340–1347.

- Haik MN, Alburquerque-Sendin F, Moreira RF, et al. Effectiveness of physical therapy treatment of clearly defined subacromial pain: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(18):1124–1134.

- Kelly SM, Wrightson PA, Meads CA. Clinical outcomes of exercise in the management of subacromial impingement syndrome: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2010;24(2):99–109.

- Bury J, West M, Chamorro-Moriana G, et al. Effectiveness of scapula-focused approaches in patients with rotator cuff related shoulder pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Man Ther. 2016;25:35–42. Epub 2016 Jun 4. PMID: 27422595.

- Littlewood C, Ashton J, Chance-Larsen K, et al. Exercise for rotator cuff tendinopathy: a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2012;98(2):101–109.

- Dong W, Goost H, Lin XB, et al. Treatments for shoulder impingement syndrome: a PRISMA systematic review and network meta-analysis. Medicine. 2015;94(10):e510.

- Gutiérrez-Espinoza H, Araya-Quintanilla F, Cereceda-Muriel C, et al. Effect of supervised physiotherapy versus home exercise program in patients with subacromial impingement syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2020;41:34–42. Epub 2019 Nov 6. PMID: 31726386.

- Abdulla SY, Southerst D, Cote P, et al. Is exercise effective for the management of subacromial impingement syndrome and other soft tissue injuries of the shoulder? A systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration. Manual Ther. 2015;20(5):646–656.

- Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898.

- Conner M, Norman P. Predicting and changing health behavior: a social cognition approach. In: Conner M, Norman P, editors. Predicting and changing health behaviour: Research and practice with social cognition models. 3rd ed. Maidenhead, Berkshire: Open University Press; 2015.

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655.

- Michie S, Wood C. Health behavior change techniques. In: Conner M, Norman P, editors. Predicting and changing health behaviour: research and practice with social cognition models. 3rd ed. Maidenhead, Berkshire: Open University Press; 2015.

- Michie S, Campbell R, Brown J, et al. ABC of theories of behavior change. London: Silverback Publishing; 2014.

- Painter J, Borba C, Hynes M, et al. The use of theory in health behavior research from 2000 to 2005: A Systematic Review. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35:358–362.

- Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95.

- Meade LB, Bearne LM, Sweeney LH, et al. Behaviour change techniques associated with adherence to prescribed exercise in patients with persistent musculoskeletal pain: Systematic review. Br J Health Psychol. 2019;24(1):10–30.

- Willett M, Duda J, Fenton S, et al. Effectiveness of behaviour change techniques in physiotherapy interventions to promote physical activity adherence in lower limb osteoarthritis patients: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0219482.

- Desmeules F, Cote CH, Fremont P. Therapeutic exercise and orthopedic manual therapy for impingement syndrome: a systematic review. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13(3):176–182.

- Kromer TO, Tautenhahn UG, de Bie RA, et al. Effects of physiotherapy in patients with shoulder impingement syndrome: a systematic review of the literature. J Rehabil Medic. 2009;41(11):870–880.

- Kuhn JE. Exercise in the treatment of rotator cuff impingement: a systematic review and a synthesized evidence-based rehabilitation protocol. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(1):138–160.

- Hanratty CE, McVeigh JG, Kerr DP, et al. The effectiveness of physiotherapy exercises in subacromial impingement syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Seminars Arthritis Rheumatism. 2012;42(3):297–316.

- Verhagen AP, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Burdorf A, et al. Conservative interventions for treating work-related complaints of the arm, neck or shoulder in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(12):Cd008742.

- Bárány I, Vu V. Central limit theorems for Gaussian polytopes. Ann Probab. 2007;35(4):1593–1621.

- Sekhar S, Ramlingam A. Is 30 the magic number? Issues on sample size estimate. Nat J Commun Med. 2013;4(1):175–179.

- Lewis J. Rotator cuff related shoulder pain: Assessment, management and uncertainties. Manual Ther. 2016;23:57–68.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000097.

- Bennell K, Wee E, Coburn S, et al. Efficacy of standardised manual therapy and home exercise programme for chronic rotator cuff disease: randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ (Clinical Research ed). 2010;340:c2756.

- Brox JI, Staff PH, Ljunggren AE, et al. Arthroscopic surgery compared with supervised exercises in patients with rotator cuff disease (stage II impingement syndrome). BMJ (Clinical Research ed). 1993;307(6909):899–903.

- Crawshaw DP, Helliwell PS, Hensor EM, et al. Exercise therapy after corticosteroid injection for moderate to severe shoulder pain: large pragmatic randomised trial. BMJ (Clinical Research ed). 2010;340(jun28 1):c3037–c3037.

- Dickens VA, Williams JL, Bhamra MS. Role of physiotherapy in the treatment of subacromial impingement syndrome: a prospective study. Physiotherapy. 2005;91(3):159–164.

- Elsodany AM, Alayat MSM, Ali MME, et al. Long-Term Effect of Pulsed Nd:YAG Laser in the treatment of patients with rotator cuff tendinopathy: A randomized controlled trial. Photomed Laser Surg. 2018;36(9):506–513.

- Gutierrez-Espinoza H, Araya-Quintanilla F, Gutierrez-Monclus R, et al. Does pectoralis minor stretching provide additional benefit over an exercise program in participants with subacromial pain syndrome? A randomized controlled trial. Musculoskeletal Sci Pract. 2019;44:102052.

- Haahr JP, Ostergaard S, Dalsgaard J, et al. Exercises versus arthroscopic decompression in patients with subacromial impingement: a randomised, controlled study in 90 cases with a one year follow up. Ann Rheumatic Dis. 2005;64(5):760–764.

- Heron SR, Woby SR, Thompson DP. Comparison of three types of exercise in the treatment of rotator cuff tendinopathy/shoulder impingement syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Physiotherapy. 2017;103(2):167–173.

- Holmgren T, Oberg B, Sjoberg I, et al. Supervised strengthening exercises versus home-based movement exercises after arthroscopic acromioplasty: a randomized clinical trial. J Rehabil Med. 2012;44(1):12–18.

- Ingwersen KG, Jensen SL, Sorensen L, et al. Three months of progressive high-load versus traditional low-load strength training among patients with rotator cuff tendinopathy: Primary results from the double-blind randomized controlled RoCTEx Trial. Orthopaedic J Sports Med. 2017;5(8):2325967117723292.

- Ketola S, Lehtinen J, Arnala I, et al. Does arthroscopic acromioplasty provide any additional value in the treatment of shoulder impingement syndrome?: a two-year randomised controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br Vol. 2009;91(10):1326–1334.

- Kukkonen J, Joukainen A, Lehtinen J, et al. Treatment of non-traumatic rotator cuff tears: A randomised controlled trial with one-year clinical results. Bone & Joint J. 2014;96-b(1):75–81.

- Littlewood C, Bateman M, Brown K, et al. A self-managed single exercise programme versus usual physiotherapy treatment for rotator cuff tendinopathy: a randomised controlled trial (the SELF study). Clin Rehabil. 2016;30(7):686–696.

- Maenhout AG, Mahieu NN, De Muynck M, et al. Does adding heavy load eccentric training to rehabilitation of patients with unilateral subacromial impingement result in better outcome? A randomized, clinical trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol, Arthrosc. 2013;21(5):1158–1167.

- Nejati P, Ghahremaninia A, Naderi F, et al. Treatment of subacromial impingement syndrome: platelet-rich plasma or exercise therapy? A randomized controlled trial. Orthopaedic J Sports Med. 2017;5(5):2325967117702366.

- Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Taimela S, et al. Subacromial decompression versus diagnostic arthroscopy for shoulder impingement: randomised, placebo surgery controlled clinical trial. BMJ (Clinical Research ed). 2018;362:k2860.

- Seven MM, Ersen O, Akpancar S, et al. Effectiveness of prolotherapy in the treatment of chronic rotator cuff lesions. Orthopaedics & Traumatol Surg Res. 2017;103(3):427–433.

- Higgins JP, Savović J, Page MJ, (on behalf of the ROB2 Development Group), et al. Revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2); 2019. https://drive.google.com/file/d/19R9savfPdCHC8XLz2iiMvL_71lPJERWK/view.

- Bennell K, Coburn S, Wee E, et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of a physiotherapy program for chronic rotator cuff pathology: a protocol for a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2007;8:86.

- Brox JI, Gjengedal E, Uppheim G, et al. Arthroscopic surgery versus supervised exercises in patients with rotator cuff disease (stage II impingement syndrome): a prospective, randomized, controlled study in 125 patients with a 2 1/2-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8(2):102–111.

- Bøhmer A, Staff P, Brox J. Supervised exercises in relation to rotator cuff disease (impingement syndrome stages II and III): A treatment regimen and its rationale. Physiother Theory Practice. 1998;14(2):93–105.

- Haahr JP, Andersen JH. Exercises may be as efficient as subacromial decompression in patients with subacromial stage II impingement: 4-8-years' follow-up in a prospective, randomized study. Scandinavian J Rheumatol. 2006;35(3):224–228.

- Hallgren HC, Holmgren T, Oberg B, et al. A specific exercise strategy reduced the need for surgery in subacromial pain patients. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(19):1431–1436.

- Ingwersen KG, Christensen R, Sorensen L, et al. Progressive high-load strength training compared with general low-load exercises in patients with rotator cuff tendinopathy: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:27.

- Kukkonen J, Joukainen A, Lehtinen J, et al. Treatment of nontraumatic rotator cuff tears: A randomized controlled trial with two years of clinical and imaging follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg. 2015;97(21):1729–1737.

- Littlewood C, Ashton J, Mawson S, et al. A mixed methods study to evaluate the clinical and cost-effectiveness of a self-managed exercise programme versus usual physiotherapy for chronic rotator cuff disorders: protocol for the SELF study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord. 2012;13:62.

- Littlewood C, Malliaras P, Mawson S, et al. Development of a self-managed loaded exercise programme for rotator cuff tendinopathy. Physiother. 2013;99(4):358–362.

- Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Taimela S, et al. Subacromial Impingement Arthroscopy Controlled Trial (FIMPACT): a protocol for a randomised trial comparing arthroscopic subacromial decompression and diagnostic arthroscopy (placebo control), with an exercise therapy control, in the treatment of shoulder impingement syndrome. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e014087.

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action Global Adherence Interdisciplinary Network. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 2003. ISBN 92 4 154599 2. (NLM classification: W 85).

- Kortte KB, Falk LD, Castillo RC, et al. The hopkins rehabilitation engagement rating scale: Development and psychometric properties. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(7):877–884.

- Newman-Beinart N, Norton S, Dowling D, et al. The development and initial psychometric evaluation of a measure assessing adherence to prescribed exercise: the Exercise Adherence Rating Scale (EARS). Physiotherapy. 2017;103(2):180–185. Epub 2016 Nov 9. PMID: 27913064.

- McLean S, Holden MA, Potia T, et al. Quality and acceptability of measures of exercise adherence in musculoskeletal settings: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2017;56(3):426–438.

- Bollen JC, Dean SG, Siegert RJ, et al. A systematic review of measures of self-reported adherence to unsupervised home-based rehabilitation exercise programmes, and their psychometric properties. BMJ Open. 2014;4(6):e005044.

- Frost R, Levati S, McClurg D, et al. What adherence measures should be used in trials of home-based rehabilitation interventions? a systematic review of the validity, reliability, and acceptability of measures. Archiv Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(6):1241–1256.e45.

- Bailey DL, Holden MA, Foster NE, et al. Defining adherence to therapeutic exercise for musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2018;54:326–331.

- Emilson C, Asenlof P, Pettersson S, et al. Physical therapists' assessments, analyses and use of behavior change techniques in initial consultations on musculoskeletal pain: direct observations in primary health care. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord. 2016;17:316.

- Kunstler BE, Cook JL, Freene N, et al. Physiotherapists use a small number of behaviour change techniques when promoting physical activity: A systematic review comparing experimental and observational studies. J Sci Med Sport. 2018;21(6):609–615.

- Hancock MJ, Hill JC. Are small effects for back pain interventions really surprising? J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2016;46(5):317–319.