Abstract

Background

Functional rehabilitation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) is often physiotherapist-led, and generally required to achieve patient goals. The quantity and duration of physiotherapist-led following could therefore potentially influence outcomes following ACLR, although the nature of this relationship is not clear.

Objective

To clarify the relationship between the quantity and duration of post-operative physiotherapy treatment and patient outcomes following ACLR.

Methods

A search of the PubMed/MEDLINE, Google Scholar, Cochrane Library, and EBSCO databases was made from inception to March 2021 to identify relevant studies. Key characteristics of the selected studies were extracted, with methodological quality evaluated using a modified version of the Downs and Black appraisal tool.

Results

The search strategy identified 1137 studies, 15 of which met inclusion criteria. Two studies were rated strong methodological quality, eight were rated moderate, and five were rated limited. Results across all 15 studies provided conflicting evidence regarding the effects of the quantity and duration of physiotherapy treatment on patient outcomes following ACLR.

Conclusions

Based on evidence of variable methodological quality, a clear relationship between the quantity and duration of physiotherapy treatment and patient outcomes following ACLR could not be established. Several themes were identified to guide future research in this area, including ensuring participant homogeneity, monitoring participant adherence to unsupervised rehabilitation, and utilising rehabilitation interventions that replicate everyday physiotherapy practice.

Keywords:

Introduction

An anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture is a devastating injury leading to a loss of structural knee stability and reduced functional ability in the short term, and decreased activity levels and an increased risk of knee osteoarthritis in the long-term [Citation1–3]. The optimal management of an ACL rupture remains elusive, with multiple factors influencing whether the injury is managed conservatively or surgically [Citation4]. ACL reconstruction (ACLR) is often considered necessary to reduce subsequent episodes of knee instability, permit a return to pre-injury activities, and preserve long-term knee joint health [Citation5–7]. Despite increased knowledge of how to prevent ACL injuries [Citation8], acceptable outcomes with conservative management [Citation9], and a high incidence of subsequent ACL injury after ACLR [Citation10], rates of ACLR have increased significantly in recent years [Citation11–13].

Multiple factors can influence patient outcomes following ACLR, including, but not limited to, age, gender, concomitant injury, time from injury to surgery, and post-injury/ACLR rehabilitation [Citation14–17]. Post-ACLR rehabilitation typically involves a significant functional component [Citation18], although may also include psychological and vocational elements [Citation19, Citation20]. The functional component typically includes exercises and activities to re-establish knee joint mobility, rebuild muscle strength, and optimise neuromuscular control [Citation21, Citation22], followed by a graduated return to pre-injury activities [Citation23].

With evidence-based clinical knowledge in rehabilitation and exercise therapy [Citation24], physiotherapists possess the requisite skills to lead the functional component of an ACLR rehabilitation programme [Citation25, Citation26]. Following ACLR, the quantity and duration of physiotherapy treatment is associated with an increased rate of return to sport [Citation27–29], a decreased re-injury risk [Citation30], greater self-reported knee function [Citation31], and better performance on functional and clinical tests [Citation17, Citation32]. Results are equivocal however, with studies also reporting the quantity and duration of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment has no effect on knee strength [Citation33], patient-reported outcomes [Citation34], and re-injury rates [Citation35].

Numerous patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) have been developed to evaluate outcomes following knee injury [Citation36], with over 50 related to the ACL deficient knee alone [Citation37]. PROMs provide an objective measure of an individual’s subjective perception in relation to their functional status [Citation38, Citation39]. The increasing use of PROMs to assess patient outcomes has realised the following benefits: increased patient-centred care, greater ability to establish treatment value, and improved patient outcomes [Citation40]. Factors associated with superior patient reported outcomes following ACLR include younger age, male sex, not smoking, receiving a hamstring tendon autograft, and the absence of concomitant injuries [Citation15].

Although physiotherapist-led rehabilitation following ACLR can have a positive effect on patient outcomes [Citation41], the optimal dosage of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment is currently unknown [Citation42]. It is also not clear how the quantity and duration of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment influences patient outcomes [Citation43]. Therefore, the aim of this review is to determine the relationship between the quantity and duration of post-operative physiotherapy treatment and patient reported outcomes following primary ACLR.

Methods

Registration

This review was registered on 1/4/21 with the PROSPERO International Register for Systematic Reviews. The ID for this review is: CRD42021240112.

Information sources

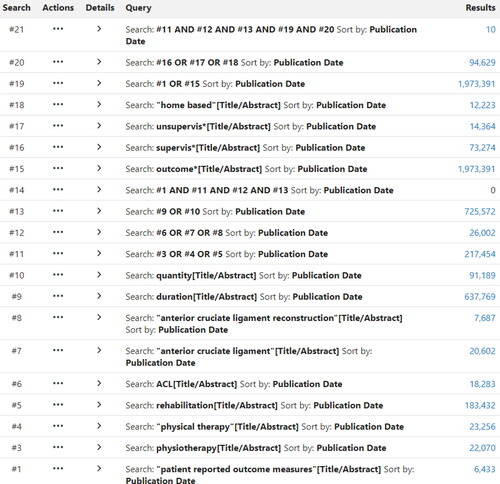

Following advice from an experienced university librarian, a literature search was undertaken by the primary investigator (identifier removed for review process) using electronic databases accessible via the Auckland University of Technology library. Pubmed/MEDLINE, Google Scholar, Cochrane Library, Sportdiscus, AMED, and CINAHL were searched from inception to March 2021. Search terms used included: patient reported outcome measures, outcome, physiotherapy, “physical therapy”, rehabilitation, ACL, “anterior cruciate ligament”, “anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction”, duration, quantity, supervis*, unsupervis*, “home based”. Boolean operators were used to combine search terms. An example of the search strategy for PubMed is shown in . Only full text studies published in English were selected. Reference lists of included studies were searched to identify any eligible studies that may have been missed during database searches.

Eligibility criteria

The following inclusion criteria were applied to select primary research studies relevant to the aim of this review:

Randomised controlled trials and non-randomised prospective cohort studies.

Participants had undergone primary ACLR.

Participants had received post-operative physiotherapy treatment.

Validated outcome data recorded prior to, and at the conclusion of, post-ACLR rehabilitation.

Studies were excluded if they met one of the following criteria:

Retrospective designs, single case studies, abstracts, and expert reviews.

Participants underwent revision ACLR.

The dosage of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment could not be quantified.

Participants were less than 18 years of age.

Participants had significant concomitant knee injury e.g. multi-ligament rupture, fracture, joint dislocation.

Study selection and data collection

Once databases searches were complete, all results were either included or excluded for review in accordance with the PRISMA study selection process for systematic reviews [Citation44]. After duplicates were removed, titles and abstracts of remaining studies were screened for relevance by one reviewer (WF). The full texts of articles that appeared relevant to the aim of the review were retrieved and independently screened by two reviewers (WF and DR). with inclusion and exclusion criteria subsequently applied. Any discrepancies regarding study selection were resolved by consensus discussion, with involvement of a third researcher (PL) if required.

Data was extracted from the selected studies by the lead author (identifier removed for review process) and tabulated under the following headings: (1) study type, (2) participant demographics, (3) intervention, (4) control, (5) outcome measures, (6) results.

Risk of bias assessment

Included studies were independently analysed by two reviewers (identifiers removed for review process) using a modified Downs and Black checklist. Any discrepancies were resolved via collective scientific debate, which included a third reviewer if necessary (identifier removed for review process). The modified Downs and Black checklist consists of 27 questions, with a maximum possible score of 28 points. The lower the overall score, the lower the methodological quality of the study. There are 4 sections, which look at reporting (x/11), external validity (x/3), internal validity (bias) (x/7) and internal validity–confounding (selection bias) (x/6) of a study. The final question relates to the overall power of the study (x/1). As utilised in previous systematic reviews [Citation45, Citation46], the last question was modified from the original version, which had a score out of five, to a score out of one, with one point being awarded if a calculation of the study’s power was included. As per previous systematic reviews [Citation45, Citation46], a quality index was calculated, with studies rated as having strong, moderate, limited, or poor methodological quality ().

Table 1. Quality index scores.

Results

Study selection

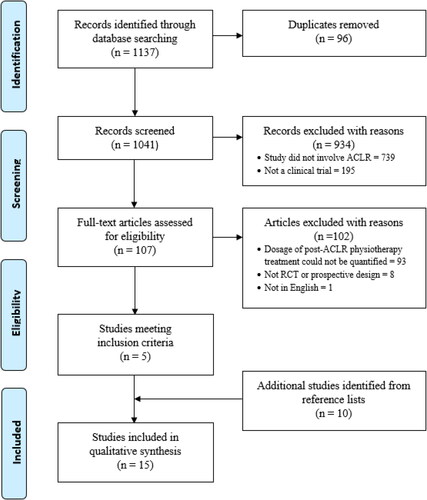

The literature search identified 1137 records, with 15 studies meeting the inclusion criteria (). Physiotherapy treatment data was then extracted from the 15 studies, which were divided into two groups – studies reporting the effects of the Quantity of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment on patient outcomes (n = 11), and studies reporting the effects of the Duration of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment on patient outcomes (n = 4).

Study characteristics

The 11 Quantity studies consisted of nine randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and two prospective cohort studies (). The four Duration studies consisted of two RCTs and two prospective cohort studies ().

Table 2. Characteristics of selected studies reporting the effects of the quantity of physiotherapy treatment on patient outcomes following ACLR.

Table 3. Characteristics of selected studies reporting the effects of the duration of physiotherapy treatment on patient outcomes following ACLR.

Participants

For Quantity studies, participant numbers ranged from 26 [Citation47, Citation48] to 145 [Citation49], with the total number of participants being 651 (30% female) (). The average age of participants across the 22 study groups was 28 years (range 21–39 years). Eight of 11 Quantity studies reported an average time between ACL injury and ACLR, which ranged from less than 12 weeks to 52 months, with one study reporting up to an 18-year interval between ACL injury and ACLR for some participants [Citation50].

For Duration studies, participant numbers ranged from 22 [Citation51] to 60 [Citation52], with the total number of participants being 173 (14% female) (). The average age of participants across the 10 study groups was 28 years (range 23–35 years). The average time from ACL injury to ACLR ranged from 56 days to 33 weeks, with one study not reporting the time between ACL injury and ACLR [Citation53].

No Quantity study reported an objective measure of pre-injury activity level for participants. Two of four Duration studies reported a pre-injury activity level for participants, with Tegner Activity Scale score ranging from five to eight [Citation51, Citation52].

Interventions

Rehabilitation interventions for the Quantity studies are summarised in . The average number of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatments for the lesser treatment groups was 3 (range 0-14). Four studies did not clearly report the duration of physiotherapy treatment for the lesser treatment group. The average number of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatments for the greater treatment groups was 21 (range 12-46).

Rehabilitation interventions for the Duration studies are summarised in . Post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment duration across all study groups ranged from 8 to 19 weeks for shorter duration groups and from 27 to 32 weeks for longer duration groups. In both studies by Beynnon and colleagues, where participants in the 19- and 32-week groups completed the same rehabilitation programme, the 19-week group completed the same volume of rehabilitation in a shorter time [Citation51, Citation54]. In both studies by Królikowska and colleagues, participants in the shorter duration groups elected to discontinue physiotherapist-supervised rehabilitation but were advised to continue with home-based rehabilitation [Citation52, Citation53].

Controls

None of the 11 Quantity studies included a control group, with all studies comparing results between groups of participants receiving different quantities of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment (). Two Duration studies included a control group where participants had not undergone ACLR and received no rehabilitation, with two studies comparing results between groups of participants undergoing post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment of different durations ().

Methodological quality

The methodological quality and Quality Index (% and categorisation) of the Quantity and Duration studies are presented as tables in Appendices Citation1 and Citation2 respectively. For Quantity studies, the average quality score was 17/28 (range 8-26), with an average Quality Index of 63% (range 21-93%). Regarding methodological quality, two studies rated ‘strong’, six rated ‘moderate’, and three rated ‘limited’. Scores ranged from 3-11/11 in the Reporting section, from 0-3/3 in the External Validity section, from 2-6/7 in the Internal Validity (Bias) section, and from 1-6/6 in the Internal Validity (Confounding) section. Only six of 11 Quantity studies reported a power analysis.

For Duration studies, the average score was 15/28 (range 10-20), with an average Quality Index of 53.5% (range 36-71%). Two studies rated ‘moderate’ methodological quality and two rated ‘limited’ methodological quality. Scores ranged from 8-10/11 in the Reporting section, from 0-1/3 in the External Validity section, from 3-5/7 in the Internal Validity (Bias) section, and from 2-6/6 in the Internal Validity (Confounding) section. Two of four Duration studies reported a power analysis.

Outcomes

A wide range of patient-reported, clinical, and functional outcome measures were used in the Quantity studies (). For patient-reported outcome measures, two studies reported a positive effect for a greater quantity of physiotherapy treatment [Citation48, Citation55], one study reported a positive effect for a lesser quantity of treatment [Citation56], and one study reported a positive effect for both greater and lesser quantities of physiotherapy treatment [Citation57]. For clinical outcome measures, two studies reported a positive effect for a greater quantity of physiotherapy treatment [Citation48, Citation58], one study reported a positive effect for less treatment [Citation49], and one study reported a positive effect for both greater and lesser quantities of physiotherapy treatment [Citation59]. For functional outcome measures, two studies reported a positive effect for a greater quantity of physiotherapy treatment [Citation48, Citation55]. Four studies reported the quantity of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment had no significant effect on any outcome measure [Citation47, Citation50, Citation60, Citation61]. Average follow up periods across all Quantity study groups ranged from 12 weeks [Citation49] to 38 months [Citation56].

A range of patient-reported, clinical, and functional outcome measures were also used in the Duration studies (). The duration of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment had no effect on patient-reported outcome measures (IKDC, KOOS, Tegner score, VAS pain score). A longer duration of physiotherapy treatment had a positive effect on functional outcomes (vertical jump performance, agility run performance) [Citation52, Citation53] and clinical outcomes (quadriceps strength, thigh circumference) [Citation52, Citation54]. Follow up periods across all Duration study groups ranged from 27 weeks [Citation52] to 24 months [Citation51, Citation54].

Strength of evidence

Meta-analysis was not possible due to the heterogeneity of the selected studies. A synthesis of the overall evidence was therefore performed using the criteria described in [Citation62].

Table 4. Overall levels of evidence.

For Quantity studies, the two studies rated ‘strong’ methodological quality either reported superior outcomes for a group of ACLR patients receiving a lower number of physiotherapy treatments compared to a group receiving a higher number, or no difference in outcomes between the groups. Of the six studies rated ‘moderate’ methodological quality, two reported the quantity of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment had no effect on patient outcomes, two reported the quantity of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment had conflicting effects on patient outcomes, and two reported the quantity of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment had a positive effect on patient outcomes. Of the three studies rated ‘limited’ methodological quality, one reported the quantity of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment had a positive effect on patient outcomes, and two reported the quantity of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment had no effect on patient outcomes. Overall, the level of evidence for the Quantity studies is best described as ‘Conflicting’ [Citation62].

For Duration studies, the two studies rated ‘moderate’ methodological quality reported the duration of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment had no effect on patient outcomes. The two studies rated ‘limited’ methodological quality reported a longer duration of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment was associated with better patient outcomes. Overall, the level of evidence for the Duration studies is best described as ‘Conflicting’ [Citation62].

Discussion

Summary of main findings

The literature search identified 15 articles where post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment data could be extracted from and used to determine the relationship between the quantity and duration of physiotherapy treatment and patient outcomes following ACLR. Based on the findings of the selected studies, it is not clear if the quantity and duration of physiotherapy treatment significantly influences patient outcomes following ACLR. Considerable heterogeneity in the methodologies of the selected studies regarding sample size, time from ACL injury to ACLR, the dosage of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment, outcome measures used, and final evaluation timeframes likely contributed to the inconclusive findings.

Comparison to existing literature

Previous systematic reviews have reported the quantity of physiotherapy supervision during post-operative rehabilitation following ACLR does not significantly influence patient outcomes [Citation21, Citation22, Citation42, Citation63–66]. All seven reviews included at least three studies from the current review, and all highlighted significant methodological inadequacies in the selected studies, including small sample sizes, absence of sample size calculation, inadequate randomisation, non-blinding of assessors, gender bias, and no reporting of compliance.

As part of wider systematic reviews on post-operative rehabilitation following various knee surgeries, a clear benefit of supervised rehabilitation over unsupervised/home-based rehabilitation following ACLR could not be established [Citation67, Citation68]. A recent scoping review on the frequency and duration of supervised rehabilitation following ACLR, which included 11 of the 15 studies from the current review, concluded moderately or minimally supervised rehabilitation is at least as effective as fully supervised high-frequency rehabilitation, and at least 6 months of supervised rehabilitation is associated with more favourable outcomes after ACLR [Citation43].

Several inconsistencies were noted between previous reviews and the current review regarding assessment of methodological quality for selected studies. For example, the study by Grant et al. (2010) was scored 4/10 by Gamble et al. (2021), indicating a lower quality study, but the current review scored Grant et al. (2010) at 93%, indicating a high-quality study. The study by Ugutmen et al. (2008) scored 90/100 by Papalia et al. (2013), which suggests a low risk of bias, whereas the Quality Index of Ugutmen et al. (2008) in the current review was scored as 36%, which suggests a high risk of bias. As different quality assessment tools assess different biases [Citation69], whichever tool is chosen to assess the methodological quality of selected studies has the potential to significantly influence the overall findings of the review.

Nine of the 11 Quantity studies compared clinic-based, physiotherapy-led rehabilitation with home-based rehabilitation. The average quantity and duration of physiotherapy for clinic-based rehabilitation and home-based rehabilitation was 21 treatments over 26 weeks and 4 treatments over 25 weeks respectively. In the 12 months following ACLR in New Zealand, patients receive an average of 10-12 physiotherapy treatments, over an average duration of 143-161 days [Citation20]. The majority of Flemish physical therapists use 41-60 treatments over 6-7 months following ACLR [Citation70]. Therefore, the quantity and duration of physiotherapy treatment in the selected studies may not be an accurate reflection of everyday physiotherapy practice. To increase external validity, future research on ACLR rehabilitation should include interventions that replicate usual physiotherapy practice.

In the first 12 weeks following ACLR, 25-38 rehabilitation sessions have been recommended [Citation23], with a physiotherapist review at least every two weeks to ensure adequate progress is maintained [Citation26]. Up to 35 physiotherapy treatments may be required in the 12 months following ACLR [Citation20]. The optimal frequency of rehabilitation supervision has yet to be determined [Citation43], and the number of physiotherapy treatments required is likely dependent on the progress of the individual patient [Citation26].

Results from this review, and previous reviews, suggest there is no singular optimal dosage of physiotherapy treatment following ACLR that can be applied to all patients. Contemporary ACLR rehabilitation is now less prescriptive, with progress through rehabilitation determined by the patient’s achievement of functional milestones, not time from surgery [Citation42, Citation71]. Similarly, the dosage of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment should also not be pre-determined, but instead be the end-product the quantity and duration of treatment required for the patient to achieve their post-operative goals [Citation26].

Other person-related factors, such as age, gender, activity levels, and concomitant injury at ACLR potentially have a greater effect on post-operative outcomes than the dosage of physiotherapy treatment. The average age of participants across all 15 studies in the current review was 28 years, with 27% of participants female. Outcomes for patients over 30 years of age, and for female patients, are typically worse following ACLR [Citation15, Citation72]. Therefore, a high percentage of male participants, and participants under 30 years of age, in a sample could result in an artificially high number of participants achieving better outcomes. However, a significant percentage of ACL injuries occur in females and in people over 30 years of age [Citation73]. Therefore, future ACL research should ensure a distribution of participants related to age and gender that represents of the current demographic of ACL injury.

A higher activity level prior to ACL injury is associated with a higher activity level following ACLR [Citation74]; however, it is not clear if patient activity level influences the dosage of physiotherapy treatment required following ACLR. Elite athletes may require more advanced rehabilitation and a greater level of supervision than recreational athletes, or conversely, elite athletes may possess a higher level of motivation to complete rehabilitation, leading to a lesser need for supervision [Citation66]. For multiple reasons, including the dosage of post-ACLR physiotherapy, a greater percentage of elite athletes return to pre-injury activity levels compared to non-elite athletes [Citation75]. Future research should investigate the dosage of physiotherapy required to achieve acceptable outcomes in ACLR patients who encompass the spectrum of activity levels.

Across 13 of the 15 studies in the current review, the time between ACL injury and ACLR ranged from 56 days to 18 years, with two studies not reporting a time [Citation48, Citation60]. A longer time to ACLR is associated with an increased risk of secondary meniscal and chondral injury due to recurrent instability episodes [Citation76, Citation77], and the presence of meniscal or chondral injury at the time of ACLR is associated with worse patient outcomes [Citation78, Citation79]. Therefore, a longer time between injury and ACLR could negatively influence patient outcomes. Only seven of 15 studies in the current review reported excluding participants with concomitant meniscal or chondral injuries at the time of ACLR, which, when combined with the wide range of times between injury and surgery, could have influenced the results of the studies in this review.

Overall, findings from the current review add to the previous literature that indicates the quantity and duration of physiotherapy treatment following ACLR does not appear to significantly influence post-operative outcomes. Previous reviews have focused on the level of supervision during post-ACLR rehabilitation, or home-based verses clinic-based rehabilitation, than the actual quantity and duration of physiotherapy treatment. The current review is therefore unique, as it is the first review to specifically address the quantity and duration of physiotherapy treatment following ACLR.

Quality of selected studies

The average Downs and Black score for all studies in the current review was 16.9/28 (range 8-26), which equates to an average Quality Index of 60%. Overall, the level of evidence is best summarised as ‘Conflicting’ [Citation62]. Several methodological issues can be identified within the selected studies. Regarding the Quantity studies, only one – Hohmann et al. (2011) – evaluated the effect of a physiotherapist-led rehabilitation program versus a fully unsupervised rehabilitation program. Across all other Quantity studies, both study groups received a degree of physiotherapist input during rehabilitation, with the quantity of that input differing between groups. It is possible the difference in the number of physiotherapy treatments between study groups was not sufficient to show any significant between-group differences [Citation66]. The lack of outcome data for completely unsupervised subjects needs to be considered when evaluating the evidence that a home-based exercise program is equally effective as a clinic-based program [Citation65].

Only 25% of studies in the current review reported, or attempted to measure, participant compliance with rehabilitation protocols. Increased compliance with rehabilitation following ACLR is associated with better patient outcomes [Citation27, Citation80]. Compliance data is an important variable due to the dose-response relationship for effectiveness [Citation21]. Measuring participant compliance with unsupervised rehabilitation may enable a more accurate comparison with patient outcomes following supervised rehabilitation.

Studies published more recently have shown a positive association between the quantity of post-ACLR rehabilitation and patient outcomes [Citation43], and results of the current review support that finding. Three Quantity studies in the current review were published from 2019 onwards [Citation48, Citation55, Citation58] – all reported a greater quantity of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment was associated with improved patient outcomes. Six Quantity studies in the current review were published prior to 2010 [Citation47, Citation49, Citation50, Citation57, Citation60, Citation61] – none reported an association between a greater amount of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment and improved patient outcomes. There is little difference between the methodological quality of the newer verses the older studies, with the average Quality Index of the post-2019 studies being 57% (range 46-64%), and the average Quality Index of the pre-2010 studies being 59.5% (range 29-89%).

There was no clear relationship between methodological quality and the overall findings of the Quantity studies. Four Quantity studies scored greater than 70% on the Quality Index. One study reported the quantity of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment had no effect on patient outcomes [Citation47], with three reporting equivocal findings regarding the quantity of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment and patient outcomes [Citation49, Citation56, Citation57]. Three studies scored less than 50% on the Quality Index – two reported the quantity of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment had no effect on patient outcomes [Citation60, Citation61] and one reported a greater amount of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment was associated with improved patient outcomes [Citation55].

The timing of the final evaluation following a post-ACLR intervention could influence the overall findings of a study. If the final evaluation was performed when subjects are unlikely to have achieved optimum function, then the final evaluation may not fully capture the total effects of any intervention. Functional measures can improve for up to two years after ACLR [Citation81]. Four Quantity studies reported results with a follow-up period of six months or less after ACLR – two reported the quantity of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment had no effect on outcomes [Citation47, Citation50], one reported less physiotherapy treatment resulted in better outcomes [Citation49], and one reported more physiotherapy treatment resulted in better outcomes [Citation58]. The remaining seven Quantity studies used follow-up periods of 12 months or greater (range 12-38 months) – two studies reported the quantity of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment had no effect on outcomes [Citation60, Citation61], two reported more physiotherapy treatment is associated with improved patient outcomes [Citation48, Citation55], one reported less physiotherapy treatment is associated with improved outcomes [Citation56], and two reported improved outcomes with more and less physiotherapy treatment [Citation57, Citation59]. Overall, our results indicate the timing of the final subject evaluation following post-ACLR rehabilitation has little influence on the results of the Quantity studies.

With regards to Duration studies, two reported the duration of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment had no effect on patient outcomes – both were rated as ‘Moderate’ quality, were published earlier, and had longer follow-up periods (24 months) [Citation51, Citation54]. Two studies reported a longer duration of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment resulted in better outcomes – both were rated ‘Limited’ quality, were published later, and had shorter follow-up periods (27-33 weeks) [Citation52, Citation53]. Due to lack of published studies, it is not possible to conclude if study quality, date of publication, and the timing of the final subject evaluation influenced the findings of the Duration studies.

Limitations

This review is not without limitations. Of the 15 included studies, only two Duration studies were conducted with the expressed aim of prospectively examining the effects of the quantity or duration of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatments on patient outcomes. None of the 11 Quantity studies specifically investigated the effects of the quantity of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment on patient outcomes. Although the intended purpose of the majority of included studies did not completely align with the intended purpose of the review, it was considered appropriate to include them, as the dosage of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment could be extracted from the articles. As such, the conclusions of this review regarding the effects of the quantity and duration of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment are based on data that was not collected for the purpose for which it has been used. The literature search was completed up to March 2021, and therefore we cannot exclude the possibility further studies have been published since this date that may provide additional insights into the research question. As we excluded articles not published in English and did not search for unpublished studies, we may not have captured all the relevant literature. Considerable heterogeneity between the included studies precluded quantitative meta-analysis, while preventing any between-study comparison of interventions and outcomes.

Conclusions

The current review has not clearly established the quantity and duration of physiotherapy treatment following ACLR has a significant effect on patient outcomes. Similar outcomes are achieved irrespective of the dosage of physiotherapy treatment. This review adds to the findings of previous reviews that have shown no clear benefit of supervised rehabilitation over home-based or unsupervised rehabilitation following ACLR. Constant monitoring of post-ACLR rehabilitation by a physiotherapist does not appear necessary, although regular therapist review allows for ongoing patient assessment, education, and progression. High-quality RCTs investigating the optimal dosage of physiotherapy treatment following ACLR, or the level of supervision required during post-ACLR rehabilitation, to achieve acceptable patient outcomes are lacking.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Beynnon BD, Johnson RJ, Abate JA, et al. Treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injuries, part I. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(10):1579–1602.

- Lindanger L, Strand T, Mølster AO, et al. Return to play and long-term participation in pivoting sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(14):3339–3346.

- Suter LG, Smith SR, Katz JN, et al. Projecting lifetime risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis and total knee replacement in individuals sustaining a complete anterior cruciate ligament tear in early adulthood. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69(2):201–208.

- Renström PA. Eight clinical conundrums relating to anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury in sport: recent evidence and a personal reflection. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(6):367–372.

- Marx RG, Jones EC, Angel M, et al. Beliefs and attitudes of members of the American academy of orthopaedic surgeons regarding the treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injury. Arthroscopy: J Arthroscopic & Related Surg. 2003;19(7):762–770.

- Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, et al. Fifty-five per cent return to competitive sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis including aspects of physical functioning and contextual factors. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(21):1543–1552.

- Sanders T, Kremers H, Bryan AJ, et al. Is anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction effective in preventing secondary meniscal tears and osteoarthritis? Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(7):1699–1707.

- Webster K, Hewett T. Meta‐analysis of meta‐analyses of anterior cruciate ligament injury reduction training programs. J Orthopaedic Res. 2018;36(10):2696–2708.

- Frobell RB, Roos HP, Roos EM, et al. Treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tear: five year outcome of randomised trial. Br Med J. 2013;346:1–12.

- Wiggins AJ, Grandhi RK, Schneider DK, et al. Risk of secondary injury in younger athletes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(7):1861–1876.

- Abram S, Price AJ, Judge A, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction and meniscal repair rates have both increased in the past 20 years in England: hospital statistics from 1997 to 2017. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(5):286–291.

- Zbrojkiewicz D, Vertullo C, Grayson JE. Increasing rates of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in young Australians, 2000–2015. Med J Aust. 2018;208(8):354–358.

- Sutherland K, Clatworthy M, Fulcher M, et al. Marked increase in the incidence of anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions in young females in New Zealand. ANZ J Surg. 2019;89(9):1151–1155.

- Cristiani R, Mikkelsen C, Edman G, et al. Age, gender, quadriceps strength and hop test performance are the most important factors affecting the achievement of a patient-acceptable symptom state after ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(2):369–380.

- Senorski E, Svantesson E, Baldari A, et al. Factors that affect patient reported outcome after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction–a systematic review of the Scandinavian knee ligament registers. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(7):410–417.

- Paterno MV, Huang B, Thomas S, et al. Clinical factors that predict a second ACL injury after ACL reconstruction and return to sport: preliminary development of a clinical decision algorithm. Orthopaedic J Sports Med. 2017;5(12):1–7.

- Ebert J, Edwards P, Yi L, et al. Strength and functional symmetry is associated with post-operative rehabilitation in patients following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(8):2353–2361.

- Andrade R, Pereira R, van Cingel R, et al. How should clinicians rehabilitate patients after ACL reconstruction? A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) with a focus on quality appraisal (AGREE II). Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(9):512–519.

- Ardern CL, Kvist J, Webster KE. Psychological aspects of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2016;24(1):77–83.

- Fausett W, Wilkins F, Reid D, et al. Physiotherapy treatment and rehabilitation following anterior cruciate ligament injury in New Zealand: are we doing enough? New Zealand J Physiother. 2019;47(3):139–149.

- Risberg MA, Lewek M, Snyder-Mackler L. A systematic review of evidence for anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation: how much and what type? Phys Ther Sport. 2004;5(3):125–145.

- Andersson D, Samuelsson K, Karlsson J. Treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injuries with special reference to surgical technique and rehabilitation: an assessment of randomized controlled trials. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(6):653–685.

- Adams D, Logerstedt D, Hunter-Giordano A, et al. Current concepts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a criterion-based rehabilitation progression. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(7):601–614.

- Clark NC. The role of physiotherapy in rehabilitation of soft tissue injuries of the knee. Orthopaedics and Trauma. 2015;29(1):48–56.

- Zadro JR, Pappas E. Time for a different approach to anterior cruciate ligament injuries: educate and create realistic expectations. Sports Med. 2018;49:357–363.

- Filbay S, Grindem H. Evidence-based recommendations for the management of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2019;33(1):33–47.

- Han F, Banerjee A, Shen L, et al. Increased compliance with supervised rehabilitation improves functional outcome and return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in recreational athletes. Orthopaedic J Sports Med. 2015;3(12):1–8.

- Rosso F, Bonasia DE, Cottino U, et al. Factors affecting subjective and objective outcomes and return to play in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a retrospective cohort study. Joints. 2018;6(1):23–32.

- Yabroudi MA, Bashaireh K, Maayah M, et al. Rehabilitation duration and time of starting sport-related activities associated with return to the previous level of sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Phys Ther Sport. 2021;49:164–170.

- Law MA, Ko Y-A, Miller AL, et al. Age, rehabilitation and surgery characteristics are re-injury risk factors for adolescents following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Phys Ther Sport. 2021;49:196–203.

- Miller CJ, Christensen JC, Burns RD. Influence of demographics and utilization of physical therapy interventions on clinical outcomes and revision rates following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017;47(11):834–844.

- Królikowska A, Sikorski Ł, Czamara A, et al. Are the knee extensor and flexor muscles isokinetic parameters affected by the duration of postoperative physiotherapy supervision in patients eight months after ACL reconstruction with the use of semitendinosus and gracilis tendons autograft? Acta Bioengin Biomech. 2018;20(3):89–100.

- De Carlo MS, Sell KE. The effects of the number and frequency of physical therapy treatments on selected outcomes of treatment in patients with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1997;26(6):332–339.

- Feller J, Webster K, Taylor N, et al. Effect of physiotherapy attendance on outcome after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a pilot study. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38(1):74–77.

- Vincent YP-h, Yiu-Chung W, Patrick YS-h Role of physiotherapy in preventing failure of primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthopaedics, Trauma and Rehabil. 2017;22(1):6–12.

- Collins N, Misra D, Felson DT, et al. Measures of knee function: international knee documentation committee (IKDC) subjective knee evaluation form, knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS), knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score physical function short form (KOOS‐PS), knee outcome survey activities of daily living scale (KOS‐ADL), lysholm knee scoring scale, oxford knee score (OKS), Western Ontario and McMaster universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC), activity rating scale (ARS), and tegner activity score (TAS). Arthritis Care & Res. 2011;63(S11):S208–S228.

- Johnson DS, Smith RB. Outcome measurement in the ACL deficient knee—what’s the score? Knee. 2001;8(1):51–57.

- Dingenen B, Gokeler A. Optimization of the return-to-sport paradigm after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a critical step back to move forward. Sports Med. 2017;47(8):1487–1500.

- Haywood KL. Patient‐reported outcome I: measuring what matters in musculoskeletal care. Musculoskeletal Care. 2006;4(4):187–203.

- Kyte D, Calvert M, Van der Wees P, et al. An introduction to patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in physiotherapy. Physiotherapy. 2015;101(2):119–125.

- Grindem H, Granan L, Risberg M, et al. How does a combined preoperative and postoperative rehabilitation programme influence the outcome of ACL reconstruction 2 years after surgery? A comparison between patients in the Delaware-Oslo ACL Cohort and the Norwegian National Knee Ligament Registry. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(6):385–389.

- van Melick N, van Cingel R, Brooijmans F, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice update: practice guidelines for anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation based on a systematic review and multidisciplinary consensus. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(24):1506–1515.

- Walker A, Hing W, Lorimer A. The influence, barriers to and facilitators of anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation adherence and participation: a scoping review. Sports Med Open. 2020;6(1):32–22.

- Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. 2021;372:1–36.

- McGowan J, Reid DA, Caldwell J. Post-operative rehabilitation of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the skeletally immature child: a systematic review of the literature. Phys Ther Rev. 2017;22(3–4):153–168.

- Erdrich LM, Reid D, Mason J. Does a manual therapy approach improve the symptoms of functional constipation? A systematic review of the literature. Int J Osteopathic Med. 2020;36:26–35.

- Beard DJ, Dodd CA. Home or supervised rehabilitation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;27(2):134–143.

- Rhim HC, Lee JH, Lee SJ, et al. Supervised rehabilitation may lead to better outcome than home-based rehabilitation up to 1 year after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Medicina. 2021;57(1):1–15.

- Grant JA, Mohtadi NG, Maitland ME, et al. Comparison of home versus physical therapy-supervised rehabilitation programs after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(9):1288–1297.

- Fischer DA, Tewes DP, Boyd JL, et al. Home based rehabilitation for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Orthop Related Res. 1998;347:194–199.

- Beynnon BD, Uh BS, Johnson RJ, et al. Rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective, randomized, double-blind comparison of programs administered over 2 different time intervals. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(3):347–359.

- Królikowska A, Sikorski Ł, Czamara A, et al. Effects of postoperative physiotherapy supervision duration on clinical outcome, speed, and agility in males 8 months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:6823–6831.

- Królikowska A, Czamara A, Szuba Ł, et al. The effect of longer versus shorter duration of supervised physiotherapy after ACL reconstruction on the vertical jump landing limb symmetry. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:1–7.

- Beynnon BD, Johnson RJ, Naud S, et al. Accelerated versus nonaccelerated rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective, randomized, double-blind investigation evaluating knee joint laxity using roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(12):2536–2548.

- Przybylak K, Sibiński M, Domżalski M, et al. Supervised physiotherapy leads to a better return to physical activity after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2019;59(9):1551–1557.

- Grant JA, Mohtadi NG. Two-to 4-year follow-up to a comparison of home versus physical therapy-supervised rehabilitation programs after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(7):1389–1394.

- Revenäs Å, Johansson A, Leppert J. A randomized study of two physiotherapeutic approaches after knee ligament reconstruction. Adv Physiother. 2009;11(1):30–41.

- Lim J-M, Cho J-J, Kim T-Y, et al. Isokinetic knee strength and proprioception before and after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a comparison between home-based and supervised rehabilitation. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2019;32(3):421–429.

- Hohmann E, Tetsworth K, Bryant A. Physiotherapy-guided versus home-based, unsupervised rehabilitation in isolated anterior cruciate injuries following surgical reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(7):1158–1167.

- Schenck RC, Blaschak M, Lance ED, et al. A prospective outcome study of rehabilitation programs and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(3):285–290.

- Ugutmen E, Ozkan K, Kilincoglu V, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction by using otogeneous hamstring tendons with home-based rehabilitation. J Int Med Res. 2008;36(2):253–259.

- Van Tulder M, Furlan A, Bombardier C, et al. Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the cochrane collaboration back review group. Spine. 2003;28(12):1290–1299.

- Wright RW, Preston E, Fleming BC, et al. ACL reconstruction rehabilitation: a systematic review part I. J Knee Surg. 2008;21(3):217–224.

- Kruse L, Gray B, Wright R. Rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(19):1737–1748.

- Lobb R, Tumilty S, Claydon LS. A review of systematic reviews on anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction rehabilitation. Phys Ther Sport. 2012;13(4):270–278.

- Gamble AR, Pappas E, O’Keeffe M, et al. Intensive supervised rehabilitation versus less supervised rehabilitation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport. 2021;24(9):862–870.

- Papalia R, Vasta S, Tecame A, et al. Home-based vs supervised rehabilitation programs following knee surgery: a systematic review. Br Med Bull. 2013;108(1):55–72.

- Coppola SM, Collins SM. Is physical therapy more beneficial than unsupervised home exercise in treatment of post surgical knee disorders? A systematic review. The Knee. 2008;16(3):171–175.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Higgins JP. Tools for assessing risk of reporting biases in studies and syntheses of studies: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):1–16.

- Dingenen B, Billiet B, de Baets L, et al. Rehabilitation strategies of flemish physical therapists before and after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: an online survey. Phys Ther Sport. 2021;49:68–76.

- Meredith SJ, Rauer T, Chmielewski TL, et al. Return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament injury: panther symposium ACL injury return to sport consensus group. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthroscop. 2020;28:2403–2414.

- Tan SHS, Lau BPH, Khin LW, et al. The importance of patient sex in the outcomes of anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(1):242–254.

- Sanders T, Maradit H, Bryan AJ, et al. Incidence of anterior cruciate ligament tears and reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(6):1502–1507.

- Dunn WR, Spindler KP, Amendola A, et al. Predictors of activity level two years after ACL reconstruction: MOON ACLR cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(10):2040.

- Lai CC, Ardern CL, Feller JA, et al. Eighty-three per cent of elite athletes return to preinjury sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review with meta-analysis of return to sport rates, graft rupture rates and performance outcomes. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(2):128–138.

- Granan L-P, Bahr R, Lie SA, et al. Timing of anterior cruciate ligament reconstructive surgery and risk of cartilage lesions and meniscal tears: a cohort study based on the Norwegian National Knee Ligament Registry. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):955–961.

- Sommerfeldt M, Raheem A, Whittaker J, et al. Recurrent instability episodes and meniscal or cartilage damage after anterior cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review. Orthopaedic J Sports Med. 2018;6(7):1–9.

- Cinque ME, Chahla J, Mitchell JJ, et al. Influence of meniscal and chondral lesions on patient-reported outcomes after primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction at 2-year follow-up. Orthopaedic J Sports Med. 2018;6(2):1–6.

- Cox CL, Huston LJ, Dunn WR, et al. Are articular cartilage lesions and meniscus tears predictive of IKDC, KOOS, and Marx activity level outcomes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? A 6-year multicenter cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1058–1067.

- Pizzari T, Taylor NF, McBurney H, et al. Adherence to rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstructive surgery: implications for outcome. J Sport Rehabil. 2005;14(3):202–214.

- Roewer BD, Di Stasi SL, Snyder-Mackler L. Quadriceps strength and weight acceptance strategies continue to improve two years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Biomech. 2011;44(10):1948–1953.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Modified Downs and Black scores for studies reporting the effect of the quantity of post-ACLR physiotherapy treatment on patient outcomes.

Appendix 2. Modified Downs and Black scores for studies reporting the effect of the duration of post-ACLR physiotherapy on patient outcomes.