ABSTRACT

The Aru Islands are situated at the eastern end of the Indian Ocean, in the southern Moluccas. They are also one of the easternmost places in the world where Islam and Christianity gained a (limited) foothold in the early-modern period, and marked the outer reach of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). The present article discusses Western-Arunese relations in the seventeenth century in terms of economic exchange and political networks. Although Aru society was stateless and relatively egalitarian and eluded strong colonial control up to the late colonial period, it was still a source of natural products, such as pearls, birds-of-paradise, turtle-shells, destined for luxury consumption in Asia and Europe. Aru society was thus positioned in a global economic network while leaving it largely ungoverned. Colonial archival data yield important information about the indigenous responses to European attempts to control the flow of goods. They both support Roy Ellen’s claim that the economic flows in eastern Indonesia extended beyond the control of VOC, and provide parallels to James Scott’s thesis of state-avoidance among the ethnic minorities in mainland Southeast Asia.

KEYWORDS:

A View from Ujir

A very small island, on the very margins of the Indian Ocean, is the point of departure of the present study. This is the forested and flat Ujir island—one of the smaller components of the Aru Islands, a group of 95 tightly clustered islands in the Arafura Sea, south of New Guinea. Coming ashore, the visitor will be shown to a tidy Muslim village of modest size. However, at some distance inland, by a natural canal, a remarkable sight offers itself, which may not have been expected in this remote part of Indonesia. Ruins of impressive stone buildings are scattered in the rain forest, pieces of Chinese porcelain are strewn on the ground, a stone pier or bridge protrudes into the canal, and an old rusty cannon lies half buried in the mud next to the remains of a mosque. If the visitor asks about the origins of the ruins, he or she will only receive vague replies. While there are stories about the origin of the human population on Ujir and the coming of Islam to the place, the material remains remain obscure due to historical amnesia. There are no preserved indigenous texts to illuminate us, although there is evidence that Malay letters written in Jawi were used in the old days.Footnote1

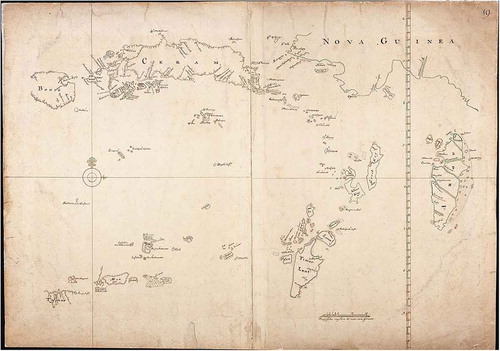

The case of Ujir points out the interesting possibilities and complications of historical research in a region that has mainly attracted anthropologists and naturalists rather than historians.Footnote2 Aru is hardly mentioned in textbooks about Indonesia, and the same goes for the other islands in southern Maluku—Kei, Tanimbar, Wetar, Kisar, Sermata, Leti, and others (see ). To the extent that they are mentioned they tend to be relegated to the role of passive appendices to colonial posts such as Banda. Although the Arunese settlements were (and, mostly, are) small-scale and scattered, the Ujir ruins nevertheless testify to its past as a center of wealth, apparently with a wide economic network. Their chronology is still a mystery, but they were already there in 1825 when a Dutch officer recorded his impressions of Aru.Footnote3

However, there are still ways to go forward. The islands were under the formal suzerainty of the VOC (Dutch East India Company) from 1623, which was later superseded by the Dutch colonial state. From the start, Dutch policy in Maluku aimed at ensuring monopoly over spices and keeping rival groups out.Footnote4 Given the economic resources of Aru, this ensured a certain output of written records—travelogues, dagregisters, letters, legal proceedings, and economic figures. If taken individually, these texts, which were written with certain aims related to political and economic concerns, may not tell us much about Arunese society. But read in context, these colonial records nevertheless indicate some indigenous processes related to trade, culture, and external contacts.

Contact Zones and the Art of Avoidance

In view of this, the present article discusses Western-Arunese relations up to the nineteenth century in terms of economic exchange and political networks. In particular, two themes are explored. First, I scrutinize the forms of interaction between colonial groups and indigenous societies, not only in terms of colonial policies, but also the choice of strategies among the Arunese. Second, I examine economic channels between Aru and the outside world that lay beyond European control, and especially the comprehensive Malukan network that went via Aru and eschewed colonial control.Footnote5 The position of Arunese societies, therefore, also entailed an element of state-avoidance. In other words, they strove to partially disentangle themselves from colonial power relations. The position of Aru is thus somewhat reminiscent of “Zomia,” the highland interior of mainland Southeast Asia in James Scott’s much-discussed Art of Not Being Governed (2009).Footnote6 Being the producers of luxury goods coveted by European and Asiatic seafarers, the Arunese made use of the possibilities of trade while striving to avoid being monitored by the center, in this case colonial Banda. This article attempts to disentangle the complexities of these cooperative and non-cooperative strategies.

Pre-European Interconnectedness

The first mention of Aru in a textual source is almost as old as the presence of Europeans in Maluku, and dates from about 1515. The Portuguese writer Tomé Pires, an indispensable source of information on the trading geography of maritime Asia, connects Aru (Daru) with the important trading communities of Banda, asserting that the Bandanese “had” Aru, Papua and Ceram, and used them for obtaining valuable goods. Aru’s speciality were Birds of Paradise, said to “come from heaven.” Feather shrouds were brought over to Banda and traded over long distances; the Turkish and Persian aristocracies used them for adornment of their dresses, and the Bengalis coveted them as well.Footnote7 Little more is known about Aru for the next 90 years, though it appears on some Portuguese maps.Footnote8

Seen in a larger context of trade patterns the tiny notes nevertheless make a lot of sense. The fifteenth century was the beginning of what Anthony Reid has famously termed Southeast Asia’s age of commerce. The role of Melaka as an entrepot after 1400, increasing Chinese knowledge about the region, the stabilization of the Ming Empire and certain Southeast Asian states, and an increasing demand for spices and natural products from the region, were factors in the rise of transregional shipping that even affected the easternmost parts of insular Southeast Asia.Footnote9 The small kingdoms of northern Maluku had risen because of the trade in cloves, and were affected by Javanese and Malay culture. They formally turned Muslim sometime in the fifteenth century and expanded their territories in the following period (and the role of Islam as a traders’ religion should be borne in mind). The nutmeg-producing Banda Islands, more to the south, were never a state but, on the contrary, consisted of a complex of local chiefs who had been converted to Islam around 1485 (if we believe Tomé Pires). It was closely allied with Ternate, the leading spice sultanate in North Maluku, after c. 1570. Banda was nevertheless at the center of an intricate system of commercial exchange. As they concentrated on nutmeg production and produced insufficient foodstuff, the Bandanese bought rice from Bima on Sumbawa, and sago and timber from islands in the near region. While the Portuguese and later the Spanish were present in Maluku in the sixteenth century, they were not able to change this system.Footnote10

The implications for Aru are explained by early Dutch documents. Arriving in the East Indies in 1596 and organized in the United East India Company (VOC) since 1602, the Dutch strove to push out their European rivals from commercially interesting areas of maritime Asia, and conquered Ambon in Maluku from the Portuguese in 1605. In the same year the first European expedition to Australia, captained by Willem Jansz, touched the Kei and Aru Islands before proceeding to Papua, the Gulf of Carpentaria and Queensland.Footnote11 Nothing much is known about this first contact, but in 1616 a nervous sea captain noted that the “murderous” Bandanese took in foodstuff and constructed boats in Kei and Aru which could conceivably be used against the Dutch.Footnote12 No massacre of Dutchmen took place, but five years later a series of political events led the VOC to commit genocide in Banda, whose original population was exterminated, enslaved or forced to flee. The VOC materials confirm what Pires had expressed, namely, that an exchange relationship existed between Aru and Banda. The ecological balance on Banda was maintained through taking in necessities from Kei-Aru, and it is likely that the latter received goods in return, presumably including trading goods brought to Banda by foreign merchants and traded for nutmeg.

From later ethnographic accounts it appears that bridewealth (bride-price) had a fundamental role in family formation in eastern Indonesia, which also applies to Aru.Footnote13 Gongs and elephant tusks were essential as status goods that were bestowed on the family of a bride. As remarked by Peter Boomgaard, the goods were usually imported items with little or no “practical” value, although this should not detract from their great ceremonially binding value. They seem to have been a byproduct of international trading relations, a pattern that was strengthened by the increasingly large quantities of items that were shipped under VOC auspices after 1602. Thus an emerging international and even intercontinental system of economic relations reified a traditional pattern such as bridewealth exchange.Footnote14

Transition to VOC Overlordship

The destruction of the economic center of Banda in 1621 had immediate consequences for the islands to the south. Surviving Bandanese fled to Kei and Aru and have maintained their ethnic identity in parts of Kei until the present.Footnote15 The Dutch, on their part, were quick to secure the valuable islands, since they still had serious rivals in maritime Southeast Asia. In a contract drawn up in 1623, the Arunese acknowledged the Company as their master, received the right to trade on Banda and Ambon, and promised to have no relations with Bandanese refugees, Ceramese or any other group.Footnote16 A similar contract was also made with Kei.

What strikes the modern reader is the ease by which the Arunese gave in to Dutch demands. In fact, while the Dutch left Aru much to its own devices, the locals asked them repeatedly to establish a more permanent foothold, in 1646 and 1653, and even requested Christian teachers. Finally, a new contract was concluded in 1658, and a fort was soon after constructed on Wokam with a tiny garrison of about twelve-fourteen men.Footnote17 The force was more symbolic than efficient, but may have served to show indigenous and external groups that the VOC claims were far from idle.

This readiness to accept the foreigners can be explained on several levels. First, the settlements (negorijen, negeris) that made the contract in 1623 were situated on the western side. They were apparently more accustomed to the culture of the archipelagic centers and mixed with immigrants via marriages. The populations of the “Backshore” (Agterwal), by contrast, had preserved the Papuan heritage to a much higher degree (although speaking Austronesian languages like the other Arunese groups). Much of the produce that made Aru an interesting place to dominate, such as tripang (edible sea cucumber), edible birds’ nests, birds-of-paradise, turtle-shell, and later on pearls, were found in the interior or east, and the gathering of the produce for export therefore demanded a precarious cooperation between westerners and easterners (in the Dutch parlance, “Alfurs”). In contrast with Kei there were no rajas or aristocracies on the islands, and the differences between commoners and settlement chiefs were gradual rather than absolute. The account of the 1623 visit stated that “there are no kings at all, and they are not governed by anyone, apart from that every negeri or village has certain orangkayas which are acknowledged as chiefs, who cannot however do or decide any bicara [deliberation] without the knowledge or prior notice of all the commoners.”Footnote18 Such a relatively egalitarian society was vulnerable to low-scale infighting. Similar to many parts of Maluku, there existed a ritual division between two bonds, the Ursia (Ulisiwa, nine-bond) and Urlima (Ulilima, five-bond), but this did not translate into political coherence.Footnote19 As an official visitor in 1698 related in his dagregister:

I then wanted to know what the correct reason was for the war. Those of Wokam, such as orangkaya Carbauio, orangkaya Hans, orangkaya Lucas and others who were commoners, related that the Barakaiese [from the Backshore] lay before Wokam for trade. Then those of Wokam, clandestinely after their manner, went away with a new capier [kind of ship] which had never been to sea and was equipped with arms, of their own accord and without permission of the [Christian school-] master, going to the southeast part of Aru. They brought away an orembai [kind of ship] from Barakai with four men. The Barakaiese who lay at Wokam for trade, hearing that, asked the Wokamese why they did so. The Wokamese replied that they did not know. The Barakaiese sailed away, saying that they were just as good people under the Company as those of Wokam. It also happened on a certain evening that the Barakaiese came with 15 sjapiers [kind of boat] to exact revenge. But the Batuley people would not allow the action and assisted the Wokamese and the ships from Mariri.Footnote20

Smaller incidents easily escalated into low-scale warfare which could involve several negeris and proved hard to stop. From this point of view the Dutch were functional as “stranger kings,” a phenomenon found in many parts of Indonesia. A resourceful stranger was able, in the best of worlds, to keep the complex of villages and linguistic areas in place. His foreignness could even be advantageous as he was not involved in local disputes and hence could give an outsider opinion.Footnote21

There were also foreign seafarers who could be seen variously as a threat or an asset depending on the circumstances. Fleets from the Makassar realm of Sulawesi were active in these waters since at least the early years of the seventeenth century and might engage in trading as well as raiding. Papuans were likewise known to have raided the islands south of Banda in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The price of political fragmentation was a marked vulnerability, for example when foreign ships captured manpower to trade as slaves. Here the Company could offer a degree of possible protection.

Parallel Religious Trajectories

The Dutch fort on Wokam was in place from c. 1659 until 1787 when it was destroyed in dramatic circumstances. The fort was situated a very short distance from the Ujirese-speaking villages on Wokam, and a short sailing trip from Ujir itself. Interestingly, Ujir and Wokam were to set in motion a process that has consequences to this day—the adoption and adaptation of the world religions of Islam and Christianity.

The coming of these related creeds in the course of the seventeenth century is fully logical when considering the political situation of maritime Southeast Asia. The strongly proselytizing agenda among Muslim archipelagic states such as Ternate, Tidore, and Makassar, was inevitably combined with political ambitions of territorial conquest. Already by 1624, Makassarese seafarers had reportedly converted some Arunese and had built mosques. A Dutch missive saw this as detrimental to VOC interests.Footnote22 The attitude was typical of its time. The VOC, a trading company to the core, was not known for its missionary zeal. Yet areas that had converted to Islam were considered more likely to oppose the Dutch. Moreover, the second charter of the VOC (1622) made it clear that the Company had spiritual duties as well as commercial aims. Areas dominated by Islam were unlikely to be converted to anything else, so the Company followed a live-and-let-live policy there out of necessity. Islam, however, could be contained through peaceful means by planting Christian schools in areas that were still “heathen.”Footnote23 Like much of eastern Indonesia, the old religion of Aru was a complex of beliefs in ancestors and spirits, but its outward expressions were so low-key that early visitors were fooled to think that the Arunese had no religion or belief in the afterlife.Footnote24

In fact, the old beliefs were strong enough for the large majority to resist conversion to Islam and Christianity up to the twentieth century. Little is known about the Islamization of the Ujirese villages, which were most probably the objects of the Makassarese foray in 1624. Surviving Muslim Bandanese fled to Kei and Aru after 1621 and obviously brought along their religion, perhaps preparing the way for conversions. According to an account from 1858, those of the west coast were “a mixed race of indigenous, of Bandanese refugees who settled there after the horrible events of 1621, furthermore the Bugis, the same whose forefathers, who came with persons who conducted trade on Aru, remained and furthered the dissemination of Islam, and finally Ceramese and other migrants from the neighbouring islands.”Footnote25 From the VOC reports it appears that some Moslems had settled in Ujir in about 1650 and that in 1668 the inhabitants asked the famous official and literatus Georg Rumphius in Ambon to bring a Muslim teacher to their island. Although Rumphius could not provide one, Islam had clearly taken root.Footnote26 Aru was, more or less, the easternmost outpost of Islam as well as of Christianity in this part of the world (see ).

Figure 1. The ruined mosque in Ujir, probably the easternmost mosque in the world in the early-modern era. Photograph: Hans Hägerdal.

Meanwhile, Reformed Protestantism made small inroads into Aru. After abortive attempts in 1636 and 1646, small congregations were formed after the establishment of the fort. Although the number of converts was small, a number of orangkayas were baptized with their kin. In about 1700 there were 257 Christians in the negeris Wokam, Wamar, Maikoor and Rumawa, and the numbers were about the same at the end of the VOC period.Footnote27 There was of course no question of proselytizing among the “Alfurs” of the interior and Backshore.

The impact of world religions upon the mindset of the Arunese is a complicated question. Acceptance of Islam and Christianity may have entailed the observance of ritual prescriptions, such as abstaining from eating pork (but not from drinking alcohol) among the Muslims, a few prayers among the Christians, and modest covering clothes among the women of both denominations. A report from 1636 notes that originally the Ujirese were completely naked, even exposing their private parts, which was likely to have changed after conversion.Footnote28

On the other hand, old beliefs in spiritual beings evidently lived on. An official visit from the Dutch hub in Banda in 1688 gave cause to the following disapproving judgment:

The propagation of the Christian religion proceeds tolerably. Since the departure of the late Reverend Du Buijs, the number of learners at the schools has recently increased, as: On Wokam, 6, namely 4 males and 2 females. On Wamar, 4 boys. And on Maikor, 2 boys, thus altogether 12 persons. According to the witness and information of the krankbezoeker [lower-rank cleric] and the schoolmasters, they are ready and suitable to receive Holy Baptism. That the good work does not progress any better is due solely to the old Arunese Christians, who can only be brought to adherence to the word of God by numerous punishments and great effort, since it is enough for them to have the name of Christians; and although they are baptized they will still always … apply their evil heathen customs, such as concubinage and the uncouth bluster at the funerals of their dead.Footnote29

In spite of the perceived problem of localization of religion, the small congregations filled a role by binding the west coast chiefs to European interests. That this should not be underestimated is shown by the loyalty shown by Christian orangkayas when Aru was struck by a Muslim-inspired anti-Dutch revolt in 1787.Footnote30 While the ways of life may have differed little between the Christian and Muslim negeris, religion became an ideological marker of importance in situations of crisis and conflict.

Goods and Trade

[T]he expectations have been rather fulfilled, since these populous islands [the Aru group] can contribute a lot to the welfare of this province [Banda] in times of peace, in particular if one finds the means to counter the arrival of the Makassarese, especially at Barakai, Mariri, Lollakrey, Trangan, Oe Oljex, Batuley and Kobroor, which, being separated from the other islands by creeks and only reachable by small perahus, deliver pearls, all sorts of tripang, karet [turtleshell] and, at the western and north-western side, a lot of sago, hogs, rice, poultry, kacang [grams], beans, etc. One also encounters a lot of dugongs at the coasts, who are reportedly good food with a pleasant taste.Footnote31

Reinier de Klerk’s account from 1756 indicates a variety of goods that the Company needed, either for the maintenance of the Banda post or for export to other parts of maritime Asia, or even Europe. Although De Klerk probably did not visit Aru himself, he drew from local reports which regarded Aru as an important economic component of the regional colonial sphere, underlined by the presence of a European fort.

As for trading items mentioned by De Klerk, pearls have remained an obvious attraction of Aru up to the present.Footnote32 They are easy to store and transport, and are coveted on a global scale. For the Dutch, pearls, together with the diamonds of West Borneo, were thus the ultimate items. The only problem was that the pearl oysters were mainly found on the Backshore where the hand of the VOC was felt lightly. The records also suggest that pearl-fishing was not an old pursuit on Aru. One of the earliest references comes from 1660 when a krankbezoeker explored the possibilities in the wake of the establishment of the fort:

[He found that] Aru consists of several small islands or peninsulas, here and there having large inlets as small lakes. When he wandered along the shore and searched for rarities and fruits of the sea, he found some oysters where there were small pearls, some very small and others somewhat larger, having no mean form and lustre. … One, with the size of a white pea, was shown to him. The owner asked 4 to 5 fathoms of textile for it, which he [the krankbezoeker] did not possess. From this it appears that these people may still not have any idea about these sea riches.Footnote33

The report added that divers would be needed to harvest the pearls. Although the early attempts to get regular deliveries were disappointing, a real pearling business in fact evolved in the course of the VOC era, with Barakai in the southeast as its center. In 1745 pearls for 579 reals were obtained at the Barakai reef and brought to Banda, of which one tenth was due to the Company itself. The pearls of Barakai (Workay) were often emphasized in the notes about Aru in the official Generale Missiven, in spite of great fluctuations in supply. When the preacher Verbeet visited Aru in 1759, he found that most of the non-baptized Christians from the west side were busy going to the Backshore with the Banda burghers to obtain pearls.Footnote34 No detailed account of the methods of pearl-fishing have been found so far in the VOC archives, but an account from 1824 by the official Bik gives a brief description. The merchants agreed to pay the local villagers an amount of arrack, textiles, etc. against 100 pearl oysters. The divers then went to the pearl bank which was 4–5 fathoms deep, which was hard work. Staying long under water sometimes gave them a bloody nose and mouth. Among all the small and sometimes black pearls, some large ones were occasionally found.Footnote35

Tripang or edible sea cucumber was probably more important due to the steadier supply. Here, too, the first detailed account is by Bik in 1824. A number of negeris at the Backshore delivered the valuable item, one of them called Afara usually gathered 350 picul (350 x 61 kilograms). Hundreds of women and children with baskets on their backs looked for tripang at the ebb, walking across the reefs with iron-tipped spears. At 2 to 4 feet they used small canoes. For more distant spots the Alfurs and their family members went with larger perahus with a peculiar appearance. Three or four huts were constructed on the boats for the family members. The sail was made of broad strips and was fan-shaped, similar to Chinese sails. The ships were used during the west monsoon, and were pulled on the shore during the easterly monsoon. Experts kept track of twenty edible tripang species. When the tripang had been caught, it was boiled with sea water and papaya leaves, so that the thin skin went off. They subsequently preserved the tripang in a basket covered with earth until the following day. Then it was washed with water several times to get rid of the unpleasant coral smell, before it was dried on a mat. However, the tripang did not entirely lose the unpleasant smell found among all holothuries or polyps. The Chinese therefore cooked tripang with teboe or sugarcane before they used it for fat soups or ragouts. Different species fetched different prices. Moreover the price rose steeply on the long trip from Aru to China: one popular species fetched 120 reals per picul in China—on Aru itself the price was 10–15 reals per picul.Footnote36 In other words, there was money to be made, but not in the first place by the Arunese themselves. This, of course, had to be balanced against the risks and ardor of the long sea trips conducted by the merchants.

Birds-of-paradise and King’s birds were also articles of note, as seen from the description by François Valentijn:

Those from Aru call this bird Wowi Wowi, and those of the Papuan Islands Sopeloo, but we say King’s bird. It is also brought from the Aru Islands, and is particular to be found in Ujir, a very well-known village there. Its nest is not known by the Arunese; however, they say they believe that this bird, just like the Bird-of-paradise, comes from New Guinea, and stays in the dry or west monsoon. Its habitat is not actually in this land.

[King’s birds] are not shot with arrows like the last-mentioned, but are caught by applying Gamboto, or Bird Glue from the Soekom fruit. It is killed at once, [intestines] taken out, dried, and bound between two borrekens [?]. Thus they preserve them until they bring them to Banda where they are usually just as expensive as the Birds-of-paradise.Footnote37

Judging from Valentijn’s account Ujir was a main port of export of the birds, which were probably hunted in the inland and brought to the little Muslim island. Edible birds’ nests were another avifauna-related product which, like tripang, was mainly intended for wealthy Chinese and fetched high prices. As for other products: Sago and grams (kacang) were brought to Banda in some quantities, and so were slaves who had lost their freedom in the frequent internal conflicts that wracked the islands. All of these items had importance for Banda itself: the Banda Islands were dominated by nutmeg plantations (perken) and produced insufficient foodstuff. Slaves were routinely used to work the plantations, but harsh conditions prevented natural reproduction and made steady import of new slaves a necessity.

In sum, several export items of Aru were luxury goods whose value might increase tenfold before they reached their destination in Asia or Europe. The spice trade in cloves and nutmeg, which took off in the fifteenth century, was the main rationale of foreign interest in Maluku, but the valuable Arunese natural products made for a secondary commercial route that linked into the primary one. In order to reserve this for the Company, the contract of 1623 stipulated that the Arunese may only trade with Banda and Ambon and not allow anyone else in. Later on this was restricted to Banda.

What in turn did the Arunese need from the outside and bought (or rather, bartered) from the Banda burghers? A detailed answer can be found in the Banda dagregisters which note down ship movements, complete with owners, crews and cargoes. For example, on Tuesday 3 February 1688, the burgher Jonas Hendriksz sailed from Banda to Tio’or, Kei and Aru, bringing the following merchandise:

13 gongs

100 cutlasses

1200 hatchets

115 water-containers

3 picul old iron

8½ pieces guinees textile

7 pieces bastas

4 pieces blue bolangs

12 chinz

20 parcullen (tightly woven cotton pieces)

13 kopre tallangs (telang, cloth?)

2 dozen knives

6 pounds coralFootnote38

Similar lists are found in other cargoes, which sometimes also include Chinese ceramics. The terms guinees, bastas, bolangs and chinz refer to different kinds of cloth, usually manufactured in India and exported to the East Indies on Dutch keels. These lists tell us a few things about early Arunese society. First, the locals had no knowledge of metalworking and needed to import objects such as hatchets, cutlasses and knives, whether for house-building, agriculture, work in the forest, or warfare. Second, in spite of their seemingly marginal geographical position, they were well aware of the Indian-produced textiles. Third, the importance of import products for bridewealth is illustrated by the gongs, and probably the foreign clothes. From other sources we know that elephant tusks were an important part of the bridewealth, and were obviously imported from western Indonesia or Mainland Southeast Asia.

Rivaling the Dutch

The date of the permanent Dutch establishment in the Aru Islands, around 1659, is significant. It occurred in an era of unprecedented European expansion in the East Indies. The Spice Sultanates of North Maluku were subordinated in 1657–1690, Palembang in 1659, Makassar in 1667–69, Mataram in the 1670s, Banten in 1682. However, the new political landscape did not automatically grant the VOC merchants the monopoly they claimed. On the contrary, warfare and devastation led to seaborne migration which challenged the Company’s interests through alternative networks. Bugis-Makassar migrants often settled in places where European control was weak or nil, and which had been frequented in the days of the Makassar Empire. Operating in sizeable fleets of paduwakangs, they traded without VOC passes and violently resisted attempts of inspection.Footnote39 Another nuisance was the Ceram and Ceramlaut people with their network of alliances among the peoples of Maluku and their resistance against VOC control. A third force was the Papuans from the large islands of Raja Ampat and the Onin Peninsula who were fearsome raiders and loosely tied to the Tidore Sultanate.Footnote40

The small Dutch garrison of Wokam could do little to control ship movements around Aru, let alone around Kei or Tanimbar (see ). However, Banda dispatched cruisers from time to time in order to check what was going on in the Southwest and Southeast Islands. From their reports we can gain an idea about Arunese interactions with foreigners beyond the eyes of the Company. On a visit to Aru in 1732, the cruiser captain heard that the sergeant of the fort was at the Backshore to trade turtle-shells. When the sergeant came back to Wokam he related his experiences to the captain:

The sergeant Hendrik van Leeuwenberg returned from the Backshore and related that he saw eight Makassarese ships on 8 February at Barakai. The people from the ship were mostly at the reef in order to look for tripang. The sergeant then asked them if they could bring him there. They replied that they would not do that. If they did so, those of Barakai would murder them. The sergeant also reported that he saw five Makassarese ships on 5 February, close to Wokam, going north between Wokam and Ujir, showing their flag and triggering a few shots.

[…]

In the morning the wind was westerly, the air filled with rain. At noon we saw nine Makassarese ships. When they became aware of us, they laid the straps on board and rowed away from us. We lifted anchor and set sail in order to pursue them. We saw that they lay at anchor to the east of Wamar. When they saw us they lifted anchor and set sail, holding a course towards the south-southeast. At 8 bells in the afternoon we could not see them anymore since they sailed at least as fast as we did.Footnote41

In this case the foreigners from Sulawesi seemed keen to avoid trouble, keeping away from the Dutch as far as they could. The Barakaiese apparently let them gather tripang on their own accord, presumably against gifts, but the relationship was tense: if the guests brought a VOC official to the reef, the locals would react in rage. Or, at any rate, this is what the Makassarese wanted the Dutch to believe. While the Dutch may have been resented as intrusive and unaccommodating, the Company authorities nevertheless tried to check excesses during the official visits. An instruction from 1733 decreed that “you shall not cause inconvenience or use violence against the indigenous people, and prevent your people from perpetrating any such [acts], so that the indigenous are the more attracted to us.”Footnote42 Success varied widely, as the actual course of the journey showed. When in Aru, the cruiser captain heard disturbing stories from the local sergeant.

Tuesday 17 [March 1733]. After the sergeant had come back from the east of the land of Aru, to the west, he told us that he had not seen any foreign ships. However, the indigenous of Barakai Island say that a foreign Makassarese ship lies half a mile from their negeri, with a crew of 12 people who make [prepare] tripang there. The sergeant asked to remove him [it], as the Noble Company by and large did not accept that foreign ships came there. They then replied that they could not see that they were foreigners to them, who gave them strong tobacco and white rice. He also told them that if they helped him to conquer the foreign ships, they would receive the ships and 2/3 of the goods that was found, for their effort, excepting the crew and weapons which the Noble Company must have. Upon that they once again replied that they would not do that, and also that they could not understand that this could be done by others as long as they remained at their reefs and shores. Those of the negeri Krai had promised to conquer the [ships] for the Noble Company if they came ashore or to the reefs.Footnote43

The attitude of the inhabitants of Barakai was remarkably inclusive. They had difficulties following the abstract Dutch notions of foreignness, exclusion and illegality, particularly since the Makassarese brought items of the wider world. The sea around Barakai was rich in resources and the villages were situated on rocky ground and anyway hard for foreigners to capture.Footnote44 The less resourceful Krai, a settlement opposite Barakai, was however less resistant to the Dutch offer, which illustrates the fragmented world of eastern Indonesia. The frequency of Makassarese seafarers strongly suggests a system of sea routes which was used with some regularity and was endorsed by the locals, who opposed Dutch attempts to disturb it.Footnote45

But there was still another entity which offered alternative ways for exporting goods. This brings us to our initial example, the archaeologically significant site in Ujir. As early as 1623 the islanders were asked “to abstain from holding bicara [deliberations] with the expelled Bandanese and the Ceramese.”Footnote46 In spite of the contracts that Ujir had to sign with the Company, the Ceram and Ceramlaut connection evidently continued to flourish. When the Dutch reflected on the outbreak of anti-Dutch resistance in the 1780s, an official wrote:

That Ujir and its three subjected villages is the only Mohammedan negeri in Aru. It also sides with the Goramese and Ceramese. Its inhabitants are since old known as malicious good-for-nothings, always disputing with the Christians; and That this Ujir is generally harmful for Aru and is seen as an obstacle for the trade, as they have played the master, mainly since 1779, so that things have deteriorated in Aru year after year.Footnote47

These negative views of the Company official must of course be seen in context. What was threatening to the interests of Company-led trade was per definition malicious. Alternative networks such as those involving Muslim traders from East Ceram and Goram could only erode the position of the Banda post of the VOC, which already suffered economic decline in the wake of the Anglo-Dutch War (1780–84) and had few years left to live. The report also pointed out that some people in the Gorom villages Keliakat, Amar, and Daai were related with the Ujirese by intermarriage (vermaagschapt). This is interestingly confirmed by the modern tradition on Ujir, which points at an ancient pela alliance with Amar.Footnote48 The villages of East Ceram and adjacent islands were good seafarers and skilled traders and were able to take in goods delivered by “Alfurs” who were dependent on Ujir, thus bypassing the monopolies the Company tried to impose.

So, were these alternative channels of economic and familial exchange successful in the long term? The rebellion fomented by Ujir in 1787 had millenarian features and was integrated into the larger anti-Dutch revolt of the Tidorese prince Nuku.Footnote49 Though eventually suppressed, it was soon followed by resistance from the Backshore. In fact it was precisely the “illicit” Makassarese and Goromese traders who supposedly incited the people to act, and their displeasure was aggravated by the poor behavior of the European post-holders in Aru.Footnote50 But before they could conclusively deal with the situation, the Dutch in Banda were overcome by the British in 1796, following the realignments in the French Revolutionary Wars. As a result, Aru quite simply vanished into obscurity from the European point of view. There is very little information about the islands during the next twenty-eight years. When the Dutch eventually equipped a scouting expedition in 1824, officer Adriaan Johan Bik found that the Chinese and Makassarese traders were thriving in the absence of external control. The traders initially worried about the return of the white men, but Bik was able to calm them down: the old Company was gone, and the days of trade monopoly were over.Footnote51 Three decades later, Alfred Russel Wallace found the trading entrepôt Dobo on Wamar Island to be a most lively place where just about every kind of merchandise was to be found, and which was hardly disturbed by any European colonial presence.Footnote52

Conclusions

The thorny story of Aru–Dutch relations links in with the age-old question why Europe grew rich while Asia did not. The question has usually addressed the larger organized Asian regions, such as China, India and Persia, but could be posed with regard to insular Southeast Asia as well. The products of Aru, in particular pearls, Birds-of-paradise, tripang, and edible bird’s nests, fetched high prices in various parts of Eurasia and even farther, so one may ask why the islanders did not seek increased political integration and economic management—perhaps under the aegis of Islam.

Counterfactual arguments may seem vain, as there is no way of knowing what would have occurred had the VOC never materialized (it may quite simply have been replaced by the English EIC [East India Company]). It may be important, however, to note the integrative forces that were at work in the larger region. Lieberman has pointed out that a complex set of factors underpinned an invisible hand that moved Eurasia towards more complex and larger political units in the period 800–1830.Footnote53 It was a very uneven process interspersed with periods of splits and chaos, but the long-term trend towards greater state integration was clear. The beginnings of a corresponding process can also be discerned in Maluku. The stabilization of the Ming Dynasty, the rise of Melaka and the stabilization of sea routes linking parts of Asia, underpinned the establishment of Muslim sultanates in the spice-producing islands of north Maluku in the fifteenth century.Footnote54 Ternate, in particular, expanded its authority over wide areas in eastern Indonesia, allying in the 1570s with Muslim Banda in which Aru had an important complementary economic function. All this happened due to a combination of pressure from Iberian rivals, the integrating impact of a world religion, and opportunities offered by interlocking commercial systems spanning over a large part of Asia. But the process towards a stable realm in Maluku was hampered by Portuguese and Spanish interventions and was definitely stalled by the rise of the VOC.Footnote55 As Lieberman has pointed out in Strange Parallels, geographical vulnerability is crucial for understanding the different historical trajectories of mainland and maritime Southeast Asia. Until the nineteenth century the mainland was, together with Japan, Arabia, and West Europe, a protected rim zone which was relatively free from outside invasions. By contrast, the maritime part was a vulnerable zone (at any rate after 1511) which both gained and suffered from the relative access that outsiders had to its resources.Footnote56

The Dutch regulation of trade and enforcement of monopolies were dissimilar to the policies of Asian port states, and their economic disadvantages were clearly seen in the Arunese attempts to maintain alternative commercial channels. But the matter is not so simple, for there were always groups that believed that the Dutch presence was in their interest, in particular the Christian chiefs of the west side who assisted the Banda burghers in the procedures of trade. For them the Dutch could ideally act as mediating “stranger kings” and even bring modest profits. On the other hand, the relations with the Ceramese and Makassarese led to a certain influx of goods and cultural input, epitomized by the stone constructions of Ujir. In that respect Aru, together with Kei, Tanimbar et cetera shared some features of the “Zomia” of highland Southeast Asia, which was difficult for the center to control and therefore avoided state dominance until fairly late in history.Footnote57 However, this intercommunication was after all vulnerable and unable to overcome the tight Dutch control. Moreover, much of the goods bought to Aru from Dutch and Asian traders was non-utilitarian and used for bridewealth or intoxication.

Finally, there was little opportunity to overcome the political fragmentation of Aru and the other islands of southern Maluku. Anyone with the ambitions to do so would have quickly been incapacitated by the VOC. The most telling example is that of Jou Mangofa, reportedly the brother of the rebel prince Nuku of Tidore, who operated in other parts of Maluku and allied with the British in order to remove the Dutch masters. Jou Mangofa instigated the rebellion of 1787, was proclaimed king, and repeatedly defeated Dutch expeditions with the help of manpower from other parts of Maluku. After three years, however, the resources of the rebels had been exhausted and the king had been killed. The words of his adherents from Ujir epitomize the hope of at least some Arunese for a “world order” different from that offered by Europeans:

The [Ujirese chiefs] offered [the Christian chief of Wokam] a cloth and a white kerchief as token of peace with him, if he abandoned the Europeans and handed them over. They also enjoined him to become a Mohammedan instead, since he could no longer lean on the Noble Company, since they had all been exterminated in their possessions, and they henceforth must be governed by the king of Tidore, whose overwhelming power must overcome all the Company.Footnote58

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hans Hägerdal

Hans Hägerdal is Professor of History at Linnaeus University, Sweden. His research interests are Western historiography on Asia, colonial contact zones in Southeast Asia, and the history of non-literate societies. His latest publication is Savu: History and Oral Tradition on an Island of Indonesia (with Geneviève Duggan; Singapore, 2018).

Notes

1. ANRI Banda 45-1, Copy of 1658 VOC-Aru contract.

2. Hägerdal, East Indonesia and the Writing of History.

3. Some archaeological aspects of Aru, including Ujir, are treated in O’Connor, Spriggs, and Veth, Archaeology of the Aru Islands. For general aspects of Southeast Maluku, see De Jonge and Van Dijk, Forgotten Islands of Indonesia.

4. Lampers, In het spoor van de Compagnie.

5. Ellen, On the Edge of the Banda Zone.

6. Cf. Hong, “Social Formation and Cultural Identity.”

7. Pires, The Suma Oriental, 206.

8. Thomaz, “Image of the Archipelago,” plates IX, XIV, XV, XVII.

9. Reid, Southeast Asia, vols. 1–2.

10. Lape, “Contact and Conflict in the Banda Islands.”

11. Heeres, Het aandeel der Nederlanders, 5–6.

12. Tiele & Heeres, Bouwstoffen, I, 154, 158.

13. Riedel, De sluik- en kroesharige rassen, 263.

14. Boomgaard, Bridewealth and Birth Control, 220–23.

15. Kaartinen, Songs of Travel.

16. Corpus diplomaticum, 179–82.

17. Bleeker, ”De Aroe-eilanden,” 263.

18. Van Dijk, Twee togten naar de Golf van Carpentaria, 9–10.

19. Coolhaas,Generale missiven, 4, 432; Van Fraassen, Ternate, de Molukken en de Indonesische Archipel, II, 485.

20. VOC 1608, Dagregister Aru, sub 2 April 1698. All translations from Dutch are by the author.

21. The stranger king syndrome is discussed in Henley, Jealousy and Justice.

22. Coolhaas, Generale missiven, I, 166–67.

23. Niemeijer, “Dividing the Islands.”

24. Kolff, Voyages of the Dutch.

25. Bleeker, “De Aroe-eilanden,” 264.

26. VOC 1271, Banda report, f. 448; Lampers, In het spoor van de Compagnie, 37

27. Van Dam, Beschryvinge van de Oostindische Compagnie, II-1, 210.

28. Dagh-Register gehouden int Casteel Batavia. A:o 1636, 227.

29. VOC 8051 (1687-88), f. 259–63.

30. VOC 8034, Witness report, Nicolaas Harmansz, 1787; VOC 3817, Witness report, Coenraad Abrahan Schipio, 14 May 1788.

31. De Klerk, Belangrijk verslag over den staat Banda, 29–30.

32. Spyer, Memory of Trade.

33. Coolhaas, Generale missiven, 3, 316.

34. Verbeet, Memorie of getrouw verhaal, 30.

35. Bik,Dagverhaal eener reis, 73.

36. Ibid., 69–72.

37. Valentijn, Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien, III B, 313.

38. VOC 8051, Dagregister Banda, sub 3 February 1688.

39. Andaya, “Bugis-Makassar Diasporas.”

40. Widjojo, Revolt of Prince Nuku, 95–113; Ellen, On the Edge of the Banda Zone.

41. VOC 2236, Dagregister, Banda, sub 27 May 1732, f. 839–40.

42. VOC 2284, Dagregister, Banda, sub 31 May 1733, f. 671.

43. VOC 2284, Banda register, Diary, sub 17 March 1733.

44. Spyer, The Memory of Trade.

45. VOC 8330, Dagregister, sub 24 June 1737.

46. Van Dijk, Twee togten naar de Golf van Carpentaria, 6.

47. VOC 8034, Report, 30 July 1787, f. 116.

48. Interview with Ujir elders, April 2016.

49. Widjojo, Revolt of Prince Nuku.

50. Comité Oost-Indische Handel en Bezittingen, 83, 1794, f. 26–27, 251, 2.01.27.01.

51. Bik, Dagverhaal eener reis, 43.

52. Wallace, Malay Archipelago, 476–79; De Jong, “Footnote to the Colonial History.”

53. Lieberman, Strange Parallels, vol. 2.

54. Ptak, “Northern Trade Route.”

55. Andaya, World of Maluku.

56. Lieberman, Strange Parallels, vols. 1–2.

57. Hong, “Social Formation and Cultural Identity.”

58. VOC 8034, Witness account, Nicolaas Harmansz, 1787. According to his own statement, the Christian chief resolutely refused the offer, and later escaped to the Dutch in Banda.

Archives

- ANRI Banda, Arsip Nasional Republik Indonesia, Jakarta.

- VOC Archief, 1.04.02, Nationaal Archief, The Hague.

- Comité Oost-Indische Handel en Bezittingen, 2. 01.27.01, Nationaal Archief, The Hague.

Bibliography

- Andaya, Leonard Y. “The Bugis-Makassar Diasporas.” Journal of the Malay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 68, no. 1 (1995): 119–39.

- Andaya, Leonard Y. The World of Maluku. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1993.

- Bik, A. J. Dagverhaal eener reis, gedaan in het jaar 1824, tot nadere verkenning der eilanden Kefing, Goram, Groot- en Klein Kei en de Aroe-eilanden. Leiden: Sijthoff, 1928.

- [Bleeker, Pieter]. “De Aroe-eilanden, in vroeger tijd en tegenwoordig”, Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch Indië 20, no. 1 ( 1858): 257–75.

- Boomgaard, Peter. ”Bridewealth and Birth Control: Low Fertility in the Indonesian Archipelago, 1500–1900.” Population and Development Review 29 no. 2 (2003): 197–214.

- Coolhaas, W. Ph., ed. Generale Missiven van Gouverneurs-Generaal en Raden aan Heren XVII der Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, Vol. 1: 1610–1638. The Hague: Nijhoff, 1960.

- Coolhaas, W. Ph., ed. Generale missiven van Gouverneurs-Generaal en Raden aan Heren XVII der Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, Vol. 3: 1656–1674. Den Haag: Nijhoff, 1968.

- Coolhaas, W. Ph., ed. Generale missiven van Gouverneurs-Generaal en Raden aan Heren XVII der Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, Vol. 4: 1675–1686. Den Haag: M. Nijhoff, 1971.

- Corpus diplomaticum Neerlando-Indicum, Vol. 1. ‘s-Gravenhage: Nijhoff, 1907.

- Dagh-Register gehouden int Casteel Batavia.A: o1636. ‘s-Gravenhage: Nijhoff, Batavia: Landsdrukkerij, 1899.

- Dam, Pieter van. Beschryvinge van de Oostindische Compagnie. Tweede Boek, Deel 1. ‘s- Gravenhage, 1931.

- Dijk, J. van. Twee togten naar de Golf van Carpentaria: J. Carstensz 1623, J. E. Gonzal 1756: Benevens iets over den togt van G. Pool en Pieter Pietersz. Amsterdam: Scheltema, 1859.

- Ellen, Roy. On the Edge of the Banda Zone: Past and Present in the Social Organization of a Moluccan Trading Network. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2003.

- Fraassen, Christaan Frans van. “Ternate, de Molukken en de Indonesische Archipel. Van soa- organisatie en vierdeling: een studie van traditionele samenleving en cultuur in Indonesië.” Vol. 1-2. PhD diss., Leiden University, 1987.

- Hägerdal, Hans. “Eastern Indonesia and the Writing of History.” Archipel 90 (2015): 75–97.

- Heeres, J. E. Het aandeel der Nederlanders in de ontdekking van Australie, 1606–1765. Leiden, 1899.

- Henley, David. Jealousy and Justice: The Indigenous Roots of Colonial Rule in Northern Sulawesi. Amsterdam: VU, 2002.

- Hong Seok-Joon. “The Social Formation and Cultural Identity of Southeast Asian Frontier Society: Focused on the Concept of Maritime Zomia as Frontier in Connection with the Ocean and the Inland.” Journal of Marine and Island Cultures 5 (2016): 28–35.

- Jong, Chris de. “A Footnote to the Colonial History of the Dutch East Indies: The ‘Little East’ in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century.” 2013. http://www.cgfdejong.nl/Little%20East.pdf.

- Jonge, Nico de, and Toos van Dijk. Forgotten Islands of Indonesia: The Art and Culture of the Southeast Moluccas. Singapore: Periplus, 1995.

- Kaartinen, Timo. Songs of Travel, Stories of Place: Poetics of Absence in an Eastern Indonesian Society. Helsinki: Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 2010.

- Klerk, Reinier de. Belangrijk verslag over den staat Banda en omliggende eilanden aan Zijne Excellentie den Gouverneur-Generaal van Ned.-Indië Jacob Mossel. ‘s- Gravenhage: n.p, 1894.

- Kolff, D. H. Voyages of the Dutch Brig of War Dourga. London: Madden & Co, 1840.

- Lampers, M.J. n.y. “In het spoor van de Compagnie: VOC, inheemse samenleving en de gereformeerde kerk in de Zuidooster- en Zuidwestereilanden 1660–1700.” Manuscript, KITLV Library, Leiden.

- Lape, Peter. “Contact and Conflict in the Banda Islands, Eastern Indonesia, 11th–17th Centuries.” PhD diss., San Francisco State University, 2000.

- Lieberman, Victor. Strange Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800–1830. Vol. 1, Integration on the Mainland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Lieberman, Victor. Strange Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800–1830. Vol. 2, Mainland Mirrors: Europe, Japan, China, South Asia, and the Islands. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Niemeijer, Hendrik E. ”Dividing the Islands: The Dutch Spice Monopoly and Religious Change in 17th Century Maluku.” In The Propagation of Islam in the Indonesian-Malay Archipelago, edited by Alijah Gordon, 251–82. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Sociological Research Institute, 2001.

- O’Connor, Sue, Matthew Spriggs, and Peter Veth. The Archaeology of the Aru Islands, Eastern Indonesia. Canberra: ANU E Press [Terra Australis 22], 2006. https://press.anu.edu.au/publications/series/terra-australis/archaeology-aru- islands-eastern-indonesia-terra-australis-22.

- Pires, Tomé. The Suma Oriental, Vol. 1–2. London: The Hakluyt Society, 1944.

- Ptak, Roderich. “The Northern Trade Route to the Spice Islands: South China Sea—Sulu Zone—North Moluccas (14th to Early 16th Century).” Archipel 43 (1992): 27– 56.

- Reid, Anthony. Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450–1680. Vol. 1–2. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988, 1993.

- Scott, James. The Art of Not Being Governed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009.

- Spyer, Patricia. The Memory of Trade: Modernity’s Entanglements on an Eastern Indonesian Island. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000.

- Thomaz, Luís Filipe F. R. “The Image of the Archipelago in Portuguese Cartography of the 16th and Early 17th Centuries.” Archipel 49 (1995): 79–124.

- Tiele, P. A., and J. E. Heeres. Bouwstoffen voor de geschiedenis der Nederlanders in den Maleischen Archipel. Deel I–III. ‘s-Gravenhage: Nijhoff, 1886–95.

- Valentijn, François. Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien, Deel III B. Doordrecht & Amsterdam: Van Braam & Onder de Linden, 1726.

- Verbeet, Gerardus. Memorie of getrouw verhaal van alle de moeilijkheden, vervolgingen en mishandelingen, den persoon van Gerardus Verbeet, laatst geweest Predikant tot Banda, in Neerlands Oostindien aangedaan. Delft, 1762.

- Wallace, Alfred Russel. The Malay Archipelago: The Land of the Orang-Utan, and the Bird of Paradise. A Narrative of Travel, with Studies of Man and Nature. London: Macmillan, 1869.

- Widjojo, Muridan. The Revolt of Prince Nuku: Cross-Cultural Alliance-Making in Maluku, c. 1780–1810. Leiden: Brill, 2009.