Abstract

Reimagine Resilience (2023), designed and established at Teachers College, Columbia University, is an innovative program that builds awareness and understanding among educators and educational personnel in the U.S. on the precursors and causes of educational displacement in students, supporting educators in promoting belonging, connectedness, and resilience to prevent educational displacement, extremism, and radicalization among students in their schools and classrooms. The study demonstrates the effectiveness of the Reimagine Resilience Program in producing attitudinal shifts in participating education personnel as they cultivate an awareness of their own biased speech and conduct. Further, this study spotlights the Program’s efficacy in identifying ways to actively prevent educational displacement as educators gain new knowledge of protective and risk factors for radicalization and targeted violence. This study underscores the importance of innovation in pedagogy, practice, assessment, and professional training for educators and educational staff to effectively engage educators in extremism and violence prevention.

Introduction

When Alison G. Smith (Citation2021) presented her findings on “Risk Factors and Indicators associated with Radicalization in the U.S.,” drawn from projects funded by the National Institute of Justice, there were three notable findings: a) Although the definition of terrorism as ideologically motivated violence in service of a political, racial, or religious goal has scholarly consensus, the process by which this ideology is seeded requires further research; b) a lack of a sense of belonging and meaning in adolescents and young adults is a prominent risk factor of targeted violence; c) there has been a consistent focus on radicalized populations as compared to populations that are both vulnerable to and manipulable by radicalizing forces as well as populations that can interrupt or block the process of radicalization (Youngblood Citation2020). While these findings are crucial in understanding reasons for radicalization and deradicalization efforts, little to no research exists that attempts to explain radicalization pathways and potential use of educational strategies and pedagogies in classrooms to interrupt these radicalization pathways.

Spaces in which adolescents and young adults spend a considerable amount of time are in K-12 schools and college campuses. Research on triggering events and threat assessments in these spaces and outlets, both offline and online, shows that students may seek out alternative spaces of belonging subsequent to feelings of marginalization, which can lead to radicalization (Trip et al. Citation2019; Brown et al. Citation2021). The reigning orthodoxy in the field treats radicalization as a moment, caused by particular instances of bias or perceived mistreatment (Hamm & Spaaij Citation2017; Smith Citation2018; Youngblood Citation2020). This treatment of radicalization as a moment after which a person has become radicalized narrows the scope for prevention as there is simply a person prior to radicalization and post-radicalization. Consequently, there remains a conspicuous absence of a model of radicalization that informs local prevention frameworks in understanding a student’s pathway to radicalization as a process shaped by multiple factors and stakeholders. Sabic-El-Rayess, through her work on radicalization in young adults and adults in Europe, first developed such a model, tracking the sequence by which educational displacement precipitates radicalization (Sabic-El-Rayess, Citation2023, Citation2021, Citation2020; Joshi & Sabic-El-Rayess, Citation2023; Sabic-El-Rayess & Marsick, Citation2021), where educational displacement is defined as the process caused by a person lacking a sense of belonging and the absence of recognition of this person’s voice in, for example, the classroom. Educational Displacement does not necessarily mean the physical displacement from the school environment, but it always means the feeling of invisibility when a student’s story is left unrecognized in the physical or virtual classroom and therefore increases the risk for radicalization.

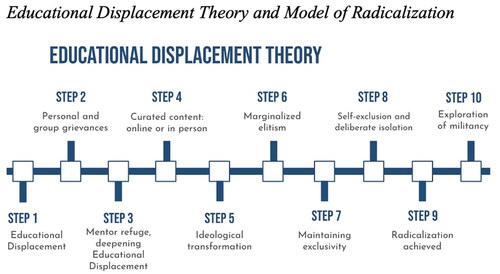

By transposing this model to the U.S. context, this study seeks to address both this theoretical lacuna in the literature and show how the Educational Displacement Model of Radicalization () is being applied in practice through a professional training program developed for educators that aims to enhance the critical role of educators and educational personnel in preventing, interrupting and, vitally, blocking the pathway to radicalization for high school and college students. Reimagine Resilience (2023), designed and established at Teachers College, Columbia University, is a program that builds awareness and understanding among educators and educational personnel in the U.S. regarding the precursors and causes of educational displacement in students, supporting educators in promoting belonging, connectedness, and resilience to prevent educational displacement, extremism, and radicalization among students in their schools and classrooms.

Figure 1. Educational displacement theory and model of radicalization. Source: Sabic-El-Rayess (Citation2021).

In this study, specifically, we present the initial analyses of data collected as part of this program’s development and evaluation. Second, we introduce an innovative methodological approach to learning assessments, data collection, and program evaluation to inform practice in violence prevention where data collection on topics of sensitive nature remains a challenge. The analyses demonstrate the effectiveness of the Reimagine Resilience (RR) Program especially in a) producing attitudinal shifts in participating education personnel as they cultivate an awareness of their own biased speech and conduct; b) identifying ways to actively prevent educational displacement resulting from biased language and behavior as educators gain new knowledge of protective and risk factors for radicalization and targeted violence; and c) gaining confidence to implement in-school practices to mitigate educational displacement. This study underscores the importance of innovation in pedagogy, practice, assessment, and professional training for educators and educational staff to effectively engage educators in extremism and violence prevention.

Background: reimaging resilience to hate through workforce and professional development

Reimagine Resilience (RR) is an innovative professional training program designed for educators and education professionals to nurture resilience as an integral capacity in their students. This professional development program draws from Educational Displacement Theory (Sabic-El-Rayess, Citation2023, Citation2021, Citation2020; Joshi & Sabic-El-Rayess, Citation2023; Sabic-El-Rayess & Marsick, Citation2021), a novel theory illustrating the ten phases that a student experiences on a pathway to violent expression (). The program builds resilience to hate and violent expression by offering a ten-part training that amplifies protective factors – such as social connectedness, nonviolent problem solving, and forming cultures of prevention in schools and classrooms. Each training component advances prevention against every step on this pathway.

In 2021, the program received a two-year Innovation Grant from the Department of Homeland Security’s Center for Prevention Programs and Partnerships (CP3) (U.S. Department of Homeland Security 2021). A team of educators and researchers at Teachers College, Columbia University, with extensive teaching experience, in-depth knowledge of education technologies, and a proven track record of building successful professional trainings that are dynamic and engaging, has built a ten-course program providing 30 hours of professional development credit. The courses are offered both online, fully asynchronously, and in a hybrid “Workshop” format, which can be offered face-to-face to partner institutions, at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Education, or any educational institution that wants to offer the training for all their educators and educational staff. The hybrid workshop can also be conducted live via Zoom. The workshop courses have associated online asynchronous components that are built in to assess student’s understanding and are required in order to receive the Certificate of Participation from Columbia University’s Teachers College. The online-only courses, as well as any asynchronous portion of the hybrid workshop courses, are housed at Columbia University’s Teachers College Canvas Learning Management System.

Each course consists of three modules within it, as well as an Introduction and Conclusion Module. Each course can range from approximately 1 to 6 hours or 0.1 to 0.6 Continuing Education Units (CEUs). Learners are encouraged and advised to enroll in all ten courses, but in the first stage of the implementation, the team is focused on delivering “Course 1” asynchronously or through the hybrid “Workshop” format. Course 1, a six-hour-long course, is the first of ten courses and must be completed before learners can move on to other courses. Learners are required to complete all activities in their entirety within one course to receive CEUs or Continuing Teacher and Leader Education (CLTE) certificates, which are distributed when requested by the learner and when the course(s) are confirmed as successfully completed by the RR team.

In this study, the findings are emergent from Workshop participation in Course 1, which is 6-hours long, that can be engaged with in a hybrid or live (in-person) modality. Participation, in terms of completing the assessments, is self-paced and therefore participants do not have a set time-limit in relation to the completion of any of the assessments. A Reimagine Resilience Workshop involved content delivery of the curricular material by two facilitators, both of whom are researchers within the team, in a hybrid or live format. Following the completion of Course 1, the participants have the option to continue progressing through the Reimagine Resilience Program by engaging with any of the nine remaining Courses.

Pedagogical approach and design to meet learning goals

The design of this professional development training is guided by participatory pedagogy and transformative learning theory. Participatory pedagogy originates in the idea that active engagement of the training’s participants is crucial to their learning process. Transformative learning theory (Mezirow Citation1997) shows that effective learning can actively transform the learner’s views, feelings, biases, values, and perceptions that frame their world. The rationale behind coupling these complementary approaches is twofold: a) both theories center the learner and base educational progress on a learner’s ability to model the skills taught in the program (Sousa et al. Citation2019); and b) educational experiences have consistently shown to increase in effectiveness when interactive elements – fundamental to both these approaches – are incorporated throughout the course of the study.

To ensure learning goals are met, the program uses methods such as participatory storytelling which engages the mind on reflection of one’s identities and supports educators’ learning. The method allows learners to experience the elements of a story through emotional participation and reflection in a community of other learners with different perspectives to share (Moratti & Sabic-El-Rayess, Citation2009; Sabic-El-Rayess, Citation2023). Learning does not occur in isolation, but in a community setting even if taken entirely asynchronously. Educators are provided with new content vocabulary and concepts for them to explore in an interactive way. They can then reflect and relate these concepts to their own lives and experiences.

Participatory pedagogies also provide a space for learners to actively create their own meaning through participation in a community they are building through the program. This is accomplished through the use of reflection and multimodal strategies engaging learners with content using multiple modes – video, audio, text, art, interactivity, and gaming – of communication and learning. The goal is to create a learning environment that mirrors a learner’s experiences outside the classroom to give meaning to them. Using various modes of delivery is a proven and effective way for teachers to design a more inclusive learning experience in their own curricula – different students have different learning styles which is unlocked by the varied mediums they can participate in. The program is designed with intentionality to create an easy communication stream among learners, but also between the Reimagine Resilience team and learners through the use of live, Padlet, Mentimeter, or Canvas native discussion forums to stimulate active learning since critical thinking and reflection are essential to the courses.

Innovation in pedagogy, practice, and assessment: shifting attitudes, biases, and views on extremism, hate, and violence

Educational displacement as a risk factor for violence in U.S. Schools

In speaking to the current programs that attempt to serve the target population, namely U.S. educators and educational personnel, a study of 18 existing anti-bias trainings in educational settings, across the country, found that the leading interventions in educational settings today result in either short-term changes or, in some cases, an increase in biased speech and conduct by educators (Forscher et. al 2019; Calanchini et. al 2020). Organizations, such as the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Learning for Justice Initiative, offers educators a list of recommendations for anti-bias practices; however, the initiative acknowledges that no current professional development intervention on a wide range of biases exists for educators (Southern Poverty Law Center Citation2020). Furthermore, there are no existing professional development opportunities for educators that focus on protective factors against targeted violence and terrorism - such as resilience, social connectedness, and nonviolent problem solving. Unlike the existing initiatives on anti-bias training, the Reimagine Resilience program has focused on protective factors against targeted violence and terrorism - resilience, social connectedness, belonging, and nonviolent problem solving - as capacities for educators and educational personnel to introduce into their in-school practices (Sabic-El-Rayess & Sullivan, Citation2020).

Enforced social isolation, engendered by the lack of peer-to-peer interactions and positive relations with family, friends, teachers, and community members, produces a chasm between an individual and their community creating a sense of displacement and invisibility. Sabic-El-Rayess (Citation2021 and Citation2020) has evinced that this sense of educational displacement often begins in schools and can be triggered by othering and alienation targeting the individual. The resulting disconnection prompts a person to seek an alternative place and community of belonging, which, for some, is found within extremist and radicalizing groups that offer a pathway to violent expression to cope with the adverse effects of educational displacement and associated grievances.

When social belonging is impaired, students feel displaced () and are particularly vulnerable to manipulation and influence from online content, without the mediating influence or the physical presence of an educator or educational personnel during the school day. In a 2020 report by the Office of Targeted Violence and Terrorism Prevention, educators have been identified, during the pandemic, as important stakeholders in both raising awareness on the risks of radicalization and in playing an active role in amplifying protective factors against radicalization and targeted violence. However, the existing research spotlights not only the noticeable lack of knowledge on educational practices that can help promote this preventative power in educators but also the lack of professional development opportunities that enhance such protective factors against radicalization in students (Smith Citation2018; Youngblood Citation2020; Qureshi Citation2020; Marone Citation2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the urgency for evidence-based professional development programs for educators to lessen educational displacement as a critical risk factor for radicalization and extremism. The lack of connectivity between an individual and society increases the likelihood of depression and anxiety-induced mental illnesses in adolescents and young adults (Loades et al. Citation2020), as well as feelings of disconnection. A 2020 report published by the Southern Poverty Law Center and the Polarization and Extremism Research and Innovation Lab (PERIL) (Citation2020) has shown that ninety-three percent of people in households with school-age children reported that their children had engaged in distance learning since the outbreak of the pandemic. In addition, nearly 15 million college students switched to online learning. In a matter of months, high school and college students drastically increased their time online as well as their exposure to propaganda and manipulative content. Considering this project’s use of a model of radicalization via Educational Displacement, this study is optimally timed to inform the prevention communities of the need for and impact of preventative professional training programs in American schools.

Innovation in assessment and learning: shifting attitudes to prevent extremism, bias, hate, and violence

Recent research on assessment of learning has shown that assessment in an educational context cannot be treated as independent of sociocultural issues such as trust and power (Curzon-Hobson, Citation2002; McLean, 2018). Assessment has to be seen as a part of learning, not something that serves an independent purpose, because assessments heavily influence students’ perceptions of what to learn and how to learn for a program (Biggs, 2012; Dann, 2014). Treating assessments as detached from learning can lead to superficial and strategic learning, where students learn “for the test” rather than learning the content. In addition, students perceive traditional summative assessments more like ‘memory tests’, rather than a process intended to deepen their understanding of the subject (Barnard et al., Citation2021). These considerations have led to the integration of knowledge-based assessments into the learning process itself in the Reimagine Resilience program.

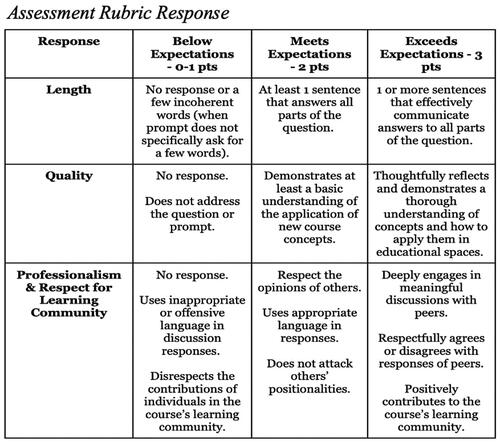

In each course, Reimagine Resilience integrates a range of knowledge-based and innovative assessments for each participant to move through. As an example, in Course 1, the Intra-Course Assessments are used to measure and gauge both content mastery and personal transformation of a participant. In Course 1, the list of assessments total 15 and include: 5 quizzes in Canvas (Learning Management System), 4 reflective discussions (emergent from the understanding of the content), 2 formative assessments in Articulate (Educational Technology Software), 3 Mentimeter (Educational Technology Integration) activities (Poll, Word-Cloud, and Text-based Reflection) and 1 Rubric Assessing Students’ Qualitative Work (Discussion Posts & OpenEnded Responses). These assessments are directly tied to the successful completion of the course and the conferring of CEU (Continuing Education Units) or CTLE (Continuing Teacher and Leader Education) Hours via a Columbia University, Teachers College Certificate of Participation. As an example, a rubric () assesses, monitors, and evaluates a participant’s responses throughout the Course. Team members examine and offer feedback on the participant’s responses across in-course assessments. If a participant’s work falls into any Below Expectations category, they will be contacted, provided with feedback based on the rubric and the course’s expectations, and expected to make the necessary changes and re-submit to receive professional development credit. For example, if a participant’s work receives a score of 0-1 points ("Below Expectations"), the participant receives a note from our Curriculum Team and is offered an opportunity to rectify the error. If a participant’s work receives a score of 3 points ("Exceeds Expectations"), the participant receives a note from our Curriculum team to recognize and affirm their work. The purpose of this process is to be transformative, rather than punitive, because a growth-oriented approach is requisite to encourage learning, self-reflection, and meaningful shift in attitudes and biases to prevent extremism, hate, and related violence.

The program embraces open-answer reflective self-assessments with instructors’ feedback in order to promote a sustainable learning effect of the Reimagine Resilience program beyond the end of the program. We deem this especially pertinent since research on educational displacement, biases, and student belonging is a continuously evolving field in which teachers have to keep up-to-date in order to promote the best results possible. A study of 18 existing anti-bias trainings in educational settings, across the country, found that the leading interventions in educational settings today lead to either short-term changes or, in some cases, an increase in biased speech and conduct by educators (Forscher et al., Citation2019; Calanchini et al. Citation2020). Therefore, a more classic approach to learning for a summative test would likely have given the wrong picture of learning fixed and invariable truths (Bourke, 2018; McLean, 2018), as well as precluded learners from a practice of self-reflecting and self-examining their biases and positionalities.

Self-reflection in self-assessments with dialogical feedback gives learners a sense of empowerment as well as increased trust in the reliability of their learnings (McLean, 2018). Trust and empowerment are two immensely important outcomes of this program that focuses on empowering teachers to engage with topics of violence, biased speech and behavior, educational displacement, and extremism in their classrooms and in fostering a culture of trust between the RR team and the teachers enrolled in the program, an assessment strategy that was deployed was intentionally reliant on self-reflection and self-assessment. Fostering a culture of trust is vital since biases, hate, extremism, and targeted violence are contentious topics in public debate, and the program asks the teachers to reflect and openly engage with these topics as well as their own experiences vis-à-vis these subjects.

Through self-reflection, learners recognize that a meaningful educational experience typically evokes a feeling of surprise, failure, or frustration, which has been shown to improve professional development in leaders and teachers (Bailey & Rehman, Citation2022; Keiny & Dreyfus, Citation1989). For instance, in RR training, the team uses a method of self-reflection (a book cover activity) where individuals are surprised, allowing them to recognize, acknowledge, reflect, and articulate their own assumptions and/or biases (Joshi, Citation2021). Disrupting a person’s current frames of thinking, biases, and assumptions is foundational to the transformative learning theory (Mezirow, Citation1997) that details the process of transformation in adults as they learn. Transformation, in this sense, is vital to the process of examining one’s own frames of thinking, bias, and assumptions. Through self-reflection, adults – and educators in particular – begin to deconstruct the old practices and beliefs and construct a new sense of self, beliefs, norms, and behaviors. Self-reflection is therefore critical to inner transformation. It has additionally been shown to increase students’ learning in online environments using tools similar to our Canvas self-reflection exercises (Gikandi, Citation2013).

It is important to keep the goal of the measurement in mind as well: Is it, for instance, absolute knowledge that should be measured to compare across participants, or are individual shifts in knowledge the matter of interest? If the interest lies in comparing knowledge across participants, traditional assessment methods such as teacher grading or quizzing might be the best option due to people overestimating their abilities. However, research has shown that there are strong correlations between students’ self-assessment and teachers’ assessments, indicating that self-assessment can be a useful and valid measurement tool, when applied in the right way (Brown et al., Citation2015; Li & Zhang, Citation2021).

Another critical issue to consider in the development of the assessment strategy is the issue of ‘sustainability.’ Sustainability in this context means that the process of learning is not finished when the program ends – the goal of an educational program must be to promote ongoing learning even after the program has finished (Boud, Citation2000; Boud & Soler, Citation2016). For an educational intervention to be sustainable, it has to equip the learners with the ability to undertake their own assessment activities in the future. During the ongoing assessments of learning that traditionally are seen as the sole domain of the assessors, learners have to be taught how to self-assess, therefore seeing assessment also as the domain of the learners themselves. Otherwise, learners will be ill-equipped to judge their progress of learning after the program has ended (Boud & Falchikov, Citation2006; Evans, 2013). In order to promote a sustainable learning environment, learners have to learn how to self-assess – primarily by reflecting upon their experiences and learnings in an open-answer format that they then get feedback on (Carless et al., Citation2011).

Students need to develop the ability to reflect on what they have learned in an unconstrained way, without, for instance, imposing the constraints of certain evaluation methods on them (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, Citation2006). RR follows this approach by continuously motivating participants to self-assess as they learn, reflect on their experiences, and provide feedback on these reflections. Therefore, as the findings in the following sections demonstrate, the participants are not only being taught the key concepts – but also the importance of self-reflection in order to promote a deeper understanding and sustainable application of these concepts as well as learning about these issues in the future.

Methodology: integrating retrospective pre- and post-test design (RPP)

As part of the comprehensive data collection to measure shifts in attitudes and knowledge gains of educators and educational staff who participate in Reimagine Resilience, we integrated an additional study measure using a retrospective pretest post-test design (RPP). In this phase of data collection, participants completed a retrospective pretest post-test survey which all educators were invited to fill out the survey at the end of the workshop using the survey platform Mentimeter – whether online or in-person. To deal with possible selection biases, we collected the data while the workshop was still going on. That way, every participant in the workshop also took part in the survey. Informed consent was acquired by presenting the participants a Powerpoint slide during the workshop informing them about the duration of the data collection, the use of the results in research publications, and that all participation was voluntary.Footnote1 Participants could decide not to take the survey and wait for 1-2 minutes while the other participants took the survey. Our sample thus consisted of educators taking part in a Reimagine Resilience workshop. To keep the survey as brief as possible, we did not include any demographic information.

As the Reimagine Resilience Program is still in its implementation stage, the data collection and analysis presented herein should be seen as preliminary: The sample sizes are expected to increase as the administration of the program continues. However, the preliminary data already demonstrates that the program has had significant effects in shifting the participants’ cognitions and attitudes pertaining to biases, educational displacement, and violence prevention.

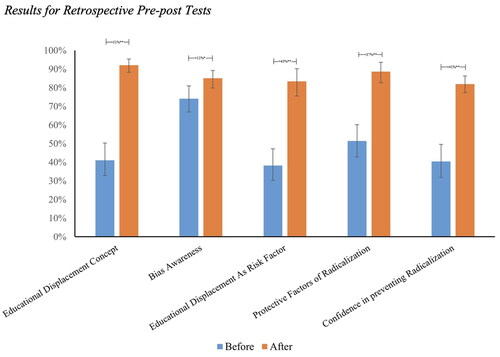

The retrospective pretest post-test design is a useful tool to measure shifts in knowledge before and after an intervention and has been applied successfully to educational program evaluations several times (Allen & Nimon, Citation2007; Coulter, Citation2012; Douglass et al., Citation2012; Drennan & Hyde, Citation2008; Geldhof et al., Citation2018; Hill, Citation2020; Little et al., Citation2020; Nimon et al., Citation2011; Pelfrey & Pelfrey, Citation2009; Sullivan & Haley, Citation2009). Other than traditional pretest post-test designs, in the RPP, data are collected only once: after the intervention. Participants are asked two questions: First, they are asked to rate their knowledge or skill level at the current point in time. Then they are asked to rate their knowledge or skill level before the intervention began. Out of these two questions, a difference score will be computed, which then is used as the measure of the shift in knowledge or skill that has occurred. This approach has the advantage of being much shorter, and being easier to administer, as the survey need only be completed at one point in time. Using the RPP, we asked workshop participants to rate a) their understanding of the concept of educational displacement, b) their understanding of educational displacement as a risk factor for radicalization, c) their knowledge about protective factors of radicalization, d) their confidence in preventing radicalization, and e) their bias awareness, before and after taking part in the workshop. The exact items as well as comparison statistics can be found in . Participants answered on a visual analogue scale ranging from 0 to 100, following modern approaches in psychological measurement (Chang & Little, Citation2018).

Table 1. Retrospective pretest post-test items.

Results

Across a sample of n = 62 educators, we compared the level of knowledge participants reported they had before and after the intervention using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. 3 educators only answered the first question and were therefore excluded from all further analyses. 3 other participants had missing data for single questions. We therefore excluded them from the respective analyses for those questions but still used their data for all other questions.

We chose the Wilcoxon signed-rank tests because the dependent variables did not seem to be normally distributed. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test assesses whether there is a significant difference between the median values of the paired observations of a participant without assuming a normal distribution of measures. Additionally, it is a more conservative and therefore more reliable test than traditional t-tests.

The retrospective pretest post-tests all showed a significant shift in knowledge and awareness regarding all of our variables of interest. In addition to , the results can be found in , which is a graphical representation including the effect size estimates of the shift in knowledge and confidence levels of the program’s participants. The error bars show 95%-Bootstrap-Confidence Intervals (Bootstrap-CIs) because Bootstrap-CIs make no assumptions about the distribution of the data.

Figure 3. Results for retrospective pre-post tests. Note. The bars show mean values for the respective retrospective pre- and post-test items. Error bars show 95%-bootstrap CIs based on 5000 bootstrap samples.

These findings provide quantitative evidence that the workshops were effective in significantly changing participants knowledge and perception of Educational Displacement and Educational Displacement as a risk factor. In addition, educators’ understanding of potentially protective factors – such as building social belonging, diverse storytelling, and social connectedness – is vital in helping them build cultures of prevention in their classrooms. Of note is that completing the program has significantly improved confidence among educators and education personnel to engage in the prevention of radicalization and targeted violence, likely in part due to their increased understanding and knowledge of Educational Displacement as a risk factor for radicalization, protective factors against hate-fueled violence, and improvement in their own bias awareness.

It is important to highlight that these shifts of knowledge are relative to oneself, not absolute or relative to other members of the cohort. One participant might have other requirements for rating their knowledge as, for instance, 90% as another participant. That means that while we cannot ascertain whether, for instance, 90% on a 100-point scale is “expert knowledge”; the evidence is encouraging and clear – the RR participants have made large knowledge gains relative to where they were prior to the training.

An additional limitation of this study is that we only observed educators who already signed up to be a part of a Reimagine Resilience workshop. These individuals were likely already motivated to learn about storytelling and violence prevention in schools. Future studies could look at which factors come into play to first build such a motivation.

Future studies could furthermore look at long-term and school-level effects of the Reimagine Resilience program. While our study provides evidence that the Reimagine Resilience workshops were effective in instigating knowledge and attitudinal shifts in the workshop participants, it would be interesting to see how educators apply these newly learned concepts in school afterwards. It would also be interesting to see how these changes impact their teaching from a student perspective, since decreasing educational displacement is the overarching goal of our initiative.

Discussion

The school and college campus are sites in which students develop their identities and worldviews. Biased speech and conduct by educators and educational personnel, can precipitate isolation, othering, and a lack of belonging – all of which are risk factors for targeted violence. Educators and educational personnel, in these contexts, do not have access to professional development opportunities that are informed by a model of radicalization that views radicalization as a pathway constituted by a sequence of processes. Consequently, educators and educational personnel do not have: a) the requisite knowledge and awareness of risk and protective factors to counter targeted violence; b) access to professional development opportunities to cultivate capacities that support the promotion of protective factors against targeted violence in their schools; and c) the ability to facilitate important dialogues with stakeholders in the larger community, such as parents, family members, faith-based leaders, and local leaders, that will fortify the local prevention framework.

To respond to this need, the team of researchers at Teachers College, Columbia University, built an innovative professional training program for educators and education personnel – aligned with the Department of Homeland Security’s Strategic Framework for Countering Terrorism and Targeted Violence that is aimed at securing the safety and security of places of gathering such as schools – to support four priorities stated in the Framework: a) help educators and educational personnel cultivate an awareness of their own and their students’ biases that can help reduce educational displacement in schools; b) strengthen the understanding of how grievances, frustrations, and othering in schools shapes both the pathway to student radicalization and the relationships between stakeholders, such as students and educators, who form the two target populations of this project, and whose speech and behavior can determine whether a student radicalizes or not; c) create a culture of resilience to violence via open communication and dialogue in schools that protects against biased behavior and speech, thereby preventing targeted violence and terrorism; and d) counter educational displacement in schools through the application of educators and educational personnel’s knowledge from the training into their classrooms, schools, and curriculum, thereby blocking and preventing the radicalization pathway.

Conclusion

This analysis evinces that the program has produced notable shifts in the understanding of risk and protective factors against hate-fueled violence. The training itself has significantly improved the confidence of educators to actively prevent and interrupt educational displacement as an early risk factor for and trigger of radicalization. By innovating and diversifying modalities of learning, teaching, assessment, and evaluation, the study sought to demonstrate that a comprehensive, evidence-based, and innovative approach to workforce development can lead to significant, meaningful, and positive shifts in attitudes, biases, knowledge gains, and readiness of educators and educational staff to engage in violence and extremism prevention in their schools and classrooms.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The Institutional Review Board Protocol Number is: IRB ID #22-106.

References

- Allen, J. M., & Nimon, K. (2007). Retrospective pretest: a practical technique for professional development evaluation. Journal of Industrial Teacher Education, 44(3), 27–42.

- Bailey, J., & Rehman, S. (2022). Don’t Underestimate the Power of Self-Reflection. https://hbr.org/2022/03/dont-underestimate-the-power-of-self-reflection, 2022

- Barnard, M., Whitt, E., & McDonald, S. (2021). Learning objectives and their effects on learning and assessment preparation: insights from an undergraduate psychology course. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(5), 673–684. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1822281

- Boud, D., & Soler, R. (2016). Sustainable assessment revisited. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(3), 400–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1018133

- Boud, D., & Falchikov, N. (2006). Aligning assessment with long‐term learning. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 31(4), 399–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930600679050

- Boud, D. (2000). Sustainable Assessment: Rethinking assessment for the learning society. Studies in Continuing Education, 22(2), 151–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/713695728

- Brown, R., Andrew, H., Todd, Ramchand, R., Palimaru, A., Rhoades, A., Hiatt, L., & S., Weilant. (2021). Violent Extremism in America: Interviews with Former Extremists and Their Families on Radicalization and Deradicalization. RAND Corporation.

- Brown, G. T., Andrade, H. L., & Chen, F. (2015). Accuracy in student self-assessment: directions and cautions for research. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 22(4), 444–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2014.996523

- Chang, R., & Little, T. D. (2018). Innovations for evaluation research: Multiform protocols, visual analog scaling, and the retrospective pretest–posttest design. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 41(2), 246–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278718759396

- Calanchini, J., Lai, C., & Klauer, K. (2020). A process-level examination of changes in implicit preferences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 121(4), 796–818.

- Carless, D., Salter, D., Yang, Min., & Lam, Joy. (2011). Developing sustainable feedback practices. Studies in Higher Education, 36(4), 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075071003642449

- Coulter, S. E. (2012). Using the retrospective pretest to get usable, indirect evidence of student learning. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 37(3), 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2010.534761

- Curzon-Hobson, A. (2002). A Pedagogy of Trust in Higher Learning. Teaching in Higher Education, 7(3), 265–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510220144770

- Douglass, J. A., Thomson, G., & Zhao, C. M. (2012). The learning outcomes race: The value of self-reported gains in large research universities. Higher Education, 64(3), 317–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9496-x

- Drennan, J., & Hyde, A. (2008). Controlling response shift bias: the use of the retrospective pre‐test design in the evaluation of a master’s programme. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(6), 699–709. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930701773026

- Forscher, P., Lai, C., Axt, J., Ebersole, C., Herman, M., Nosek, B., & Devine, P. (2019). A meta-analysis of procedures to change implicit measures of bias. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 117(3), 522–559. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000160

- Geldhof, G. J., Warner, D. A., Finders, J. K., Thogmartin, A. A., Clark, A., & Longway, K. A. (2018). Revisiting the utility of retrospective pre-post designs: the need for mixed-method pilot data. Evaluation and Program Planning, 70, 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2018.05.002

- Gikandi, J. (2013). How can open online reflective journals enhance learning in teachereducation?. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 21(1), 5–26.

- Hamm, M. S., & Spaaij, R. (2017). The Age of Lone Wolf Terrorism. Columbia University Press.

- Hill, L. G. (2020). Back to the future: Considerations in use and reporting of the retrospective pretest. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(2), 184–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025419870245

- Joshi, V. V. (2021). Book Review: The Cat I Never Named: A True Story of Love, War, and Survival (2020) written by Amra Sabic-El-Rayess and Laura L. Sullivan. New York: Bloomsbury. Global Journal of Peace Research and Praxis, 3(1)

- Joshi, V., & Sabic-El-Rayess, A. (2023). Witnessing the pathways of misinformation, hate, and radicalization: A pedagogic response. In Education in the Age of Misinformation: Philosophical and Pedagogical Explorations (pp. 97–117). Springer International Publishing.

- Keiny, S., & Dreyfus, A. (1989). Teachers’ Self‐reflection as a Prerequisite to their Professional Development. Journal of Education for Teaching, 15(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260747890150104

- Li, M., & Zhang, X. (2021). A meta-analysis of self-assessment and language performance in language testing and assessment. Language Testing, 38(2), 189–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532220932481

- Little, T. D., Chang, R., Gorrall, B. K., Waggenspack, L., Fukuda, E., Allen, P. J., & Noam, G. G. (2020). The retrospective pretest–posttest design redux: On its validity as an alternative to traditional pretest–posttest measurement. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(2), 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025419877973

- Loades, M. E., Chatburn, E., Higson-Sweeney, N., Reynolds, S., Shafran, R., Brigden, A., Linney, C., McManus, M. N., Borwick, C., & Crawley, E. (2020). Rapid Systematic Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(11), 1218–1239.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

- Marone, F. (2020). Hate in the time of coronavirus: exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on violent extremism and terrorism in the West. Security Journal, 35(1), 205–225. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41284-020-00274-y

- Mezirow, J. (1997). Transformative Learning: Theory to Practice. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 1997(74), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.7401

- Moratti, M., & Sabic-El-Rayess, A. (2009). Transitional Justice and DDR: The Case of Bosnia and Herzegovina. International Center for Transitional Justice, 6, 1–39.

- Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane‐Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self‐regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572090

- Nimon, K., Zigarmi, D., & Allen, J. (2011). Measures of program effectiveness based on retrospective pretest data: are all created equal? American Journal of Evaluation, 32(1), 8–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214010378354

- Pelfrey, W. V., Sr., & Pelfrey, W. V. Jr, (2009). Curriculum evaluation and revision in a nascent field: The utility of the retrospective pretest—posttest model in a homeland security program of study. Evaluation Review, 33(1), 54–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X08327578

- Qureshi, A. (2020). Understanding Domestic Radicalization and Terrorism. National Institute of Justice Journal, 1(1), 1–12.

- Sabic-El-Rayess, A. (2023). 6. Ending Educational Displacement. Bosnian Studies: Perspectives from an Emerging Field, 123

- Sabic-El-Rayess, A. (2021). How do people radicalize? International Journal of Educational Development, 87, 102499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2021.102499

- Sabic-El-Rayess, A. (2020). Epistemological shifts in knowledge and education in Islam: A new perspective on the emergence of radicalization amongst Muslims. International Journal of Educational Development, 73, 102148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2019.102148

- Sabic-El-Rayess, A., & Sullivan, L. L. (2020). The cat I never named: A true story of love, war, and survival. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

- Sabic-El-Rayess, A., & Marsick, V. (2021). Transformative learning and extremism. Actes de, 636

- Sabic-El-Rayess, A. (2021). The Scary truth about student radicalization: It can happen here. Education Week, March 4. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/opinion-the-scary-truth-about-student-radicalization-it-can-happen-here/2021/03

- Smith, A. (2021). Risk Factors and Indicators Associated With Radicalization to Terrorism in the United States: What Research Sponsored by the National Institute of Justice Tells Us. Needs, Risk, and Threat Assessment Workshop. U.S. Department of Justice.

- Smith, A. (2018). How Radicalization to Terrorism Occur in the United States: What Research Sponsored by the National Institute of Justice Tells Us.” National Institute of Justice.

- Sousa, J., Loizou, E., & Fochi, P. (2019). Instituting children’s rights in day to day pedagogic development. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 27(3), 299–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2019.1608116

- Southern Poverty Law Center and Polarization and Extremism Research and Innovation Lab (PERIL). (2020). Building Resilience and Confronting Risk in the COVID-19 Era. Southern Poverty Law Center.

- Southern Poverty Law Center. (2020). Critical Practices for Anti-Bias Education: Teacher Leadership. Learning for Justice. https://www.learningforjustice.org/professional-development/critical-practices-for-antibias-education-teacher-leadership.

- Sullivan, L. G., & Haley, K. J. (2009). Using a retrospective pretest to measure learning in professional development programs. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 33(3-4), 346–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668920802565052

- Trip, S., Bora, C., Marian, M., Drugas, M., & Halmajan, A. (2019). Psychological Mechanisms Involved in Radicalization and Extremism. A Rational Emotive Behavioral Conceptualization. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 437. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00437

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security. (2020). Homeland Threat Assessment (pp. 1–25).

- Youngblood, M. (2020). Extremist ideology as a complex contagion: the spread of far-right radicalization in the United States between 2005 and 2017. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00546-3