Abstract

This study presents findings on the indicators of educational displacement as an early risk factor for radicalization in school settings in the U.S. We collected and analyzed data from 301 students living in 43 U.S. states to inform the creation of Reimagine Resilience, an innovative violence prevention training program for educators and educational staff developed at Teachers College, Columbia University, and to measure early indications of educational displacement as a risk factor for radicalization. The study shows that poor teacher-student relations and multiple experiences of biased speech and behavior are significant early predictors of the students’ educational displacement. Educational displacement, in this study, is measured as a lack of social belonging in schools.

Introduction

In favor of racial and religious targeting, Darla Martin-Gorski (Citation2002) argues that racially profiling a Middle Eastern person before allowing them to board a flight ‘is making proper use of limited resources in an effort to protect the entire citizenry from violent terrorist attacks.’ This premise mirrors a broader paradigm of ostensible efficiency that has turned racialization, profiling, and the surveying of Muslims into a primary and myopic approach to addressing domestic extremism. Alimahomed-Wilson (2018) aptly calls this a ‘racialized state surveillance’ of Muslims in the United States. A study of 113 cases of FBI contacting Muslims concluded that ordinary religious practices Muslims engage in are regularly flagged as suspect by the FBI regardless of the absence of any criminal activity, demonstrating that the FBI’s actions are predicated on the assumption that Muslim identity itself is deemed a risk factor for extremism (Alimahomed-Wilson, Citation2018). Yet, most victims of extremist violence globally are Muslims themselves with one country alone – Afghanistan – accounting for 44% of 22,847 deaths inflicted through terrorism in 2020 (Ritchie et al., Citation2023).Footnote1

Selod and Embrick (Citation2013) further problematize a principal focus on ‘a Black/White paradigm’ in research on race that has neglected the changing nature of race and racism in the American context (Selod & Embrick, Citation2013). In the U.S., anti-Muslim racism is pervasive: 83% of Americans worry an act of extremism would be committed by a Muslim; and 82% of American Muslims internalize this concern (Abdo, Citation2017). American Muslims are intimately familiar with the societal backlash, racism, dehumanization, othering, discrimination, and marginalization of the American Muslim polity that follows an act of mass violence committed by a Muslim. A similar collective demonization of Christians or Jews as suspects, terrorists, or extremists is absent when a member of their community commits an act of targeted or extremist violence. Kearns et al. (Citation2019) confirm that when an act of terrorism is committed by a Muslim CNN, the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, and USA Today amplify their coverage of the incident by 758% relative to when a perpetrator is a non-Muslim. They further demonstrate that all national media sources in the U.S. increase their coverage by 357% percent when a Muslim perpetrates a violent act–though they are responsible for only 12.5% of the instances of extremist violence in the U.S., half of the news coverage on the topic is dedicated to Muslim perpetrators. It should then come as no surprise that 60% of Americans approve of racial profiling as long as it targets Muslims and Arabs (Cole and Dempsey, Citation2006). This targeting and othering is not idiosyncratic to the American environment. In the U.K., a recent report shows that anti-Muslim hate incidents have doubled in the last decade (Tellmama, Citation2023).

Anti-Muslim racism requires redress through a whole-of-society prevention approach informed by novel scholarship on terrorism, extremism, and targeted violence. We treat this collection of three terms as a collective category inclusive of hate-driven crimes targeting a particular religious, racial, or ethnic group (targeted violence) that, in many instances, also aim to achieve an ideological or political change (terrorism). However, there is limited empirical research and nuanced understanding of how and why an ordinary individual transforms into an extremist and engages in mass violence targeting specific groups, often, to achieve an ideological goal. The pathway of that individual and ideological transformation requires additional research if we are to effectively prevent hate-fueled violence in an increasingly polarized America.

Therefore, we offer an evidence-based perspective on a pathway to radicalization in the U.S. This study introduces a novel and identity-agnostic perspective on the epistemology of extremism and hate-fueled violence. In a necessary course-correction away from racializing and profiling of, for example, Muslims as terrorists, suspects, and extremists, this analysis delivers an empirical model evincing that a common trigger and early risk factor for individuals to adopt extremist perspectives is a sense of individual or collective displacement either experienced or perceived irrespective of individual geographies, ideologies, or identities (i.e. identity-agnostic). Whether we consider Lauren Manning (Manning & Manning, Citation2021), a person who successfully deradicalized from the far-right movement without committing an act of mass violence, or the likes of Anders Breivik, who murdered 77 people in a dual bomb gun-shooting attack in Oslo and Utoya (Norway) in 2011, later inspiring Brenton Tarrant, who took 51 lives in two mosques in Christchurch (New Zealand) in early 2019 who, in turn, motivated Patrick Wood to kill 23 Latinos in El-Paso (Texas)that same year, there is a common element. Each of these individuals experienced or perceived themselves to be displaced from the mainstream society, an impetus that launched their quest for an alternative place of social belonging and a sense of purpose that ultimately resulted in their radicalization.

A displacement that engenders an inner sense of invisibility in schools, workplaces, and communities ignites a search for social belonging (Sabic-El-Rayess, Citation2021). Displacement can manifest in a physical form through a decline in attendance, engagement, and even dropping out from school, community, and the workplace, but it can also remain hidden in plain sight as an internalized mobilizer of a personal quest for social belonging, meaning, visibility, purpose, and acceptance (Joshi & Sabic-El-Rayess, Citation2023). For some, that pursuit for social belonging may be met constructively if they benefit from key protective factors against radicalization, which often include a supportive community, family, school, and peer environment. For others lacking those protective forces, the search can put them on a path to radicalization.

To strengthen emerging research on educational displacement as an impetus to radicalization, this study presents findings on the indicators of educational displacement as an early risk factor for radicalization in school settings in the U.S. We collected and analyzed data from 301 students living in 43 U.S. states to inform the creation of Reimagine Resilience (Citation2023), an innovative violence prevention training program for educators and educational staff created at Teachers College, Columbia University, and to measure early indications of educational displacement as a risk factor for radicalization. The study shows that poor teacher-student relations and multiple experiences of biased speech and behavior are significant early predictors of the students’ educational displacement, measured as a lack of social belonging in schools. Moreover, the student’s racial, religious, and ethnic identities do not predict student’s sense of social belonging in school, but students’ exposure to biased speech and behavior does. In other words, it is the student’s experience of bias because of their identity –not identity itself – that produces a sense of displacement in American students and elevates the individual and societal risk of radicalization and violence. These findings were utilized to create evidence-based lessons in Reimagine Resilience, a novel professional training program for educators to prevent targeted and hate-fueled violence (Reimagine Resilience, Citation2023).

To counter the unremitting rise of extremism in the US, the study proposes that a whole-of-society and whole-of-school approach are warranted to de-normalize continued profiling of religious, ethnic, and racial groups as ‘at risk’ and ‘threat’ and instead broaden early prevention by lessening a sense of educational displacement across all racial, religious, and ethnic groups. A whole-of-society and school approach to violence prevention considers all stakeholders, especially educators and educational staff, in a community as necessary participants to prevent targeted violence. In sum, schools are the underutilized sites of prevention, and the early risk for radicalization – educational displacement – should be mitigated in schooling spaces by building training programs that raise awareness of this risk factor for radicalization as well as undermine it, by enhancing connectedness and social belonging.

Conceptualizing links between social belonging, educational displacement, radicalization, and extremism

Social belonging

To belong is to perceive oneself as integral to the community ensuring a sense of connectedness that protects from displacement and disconnection resulting in both individual and societal benefits, including lessening the risk of radicalization. People, who are socially accepted, experience and even facially express happiness (DeWall et al., Citation2009). Social belonging is an evolving state achieved through a continual process of interactive, iterative, and reciprocal relations and experiences a person shares and enjoys within their community.

Current literature exploring the intersectionality between educational displacement, extremism, bias, and social belonging in U.S. schools is limited. We examine the role of social belonging as a protective factor against the inverse of educational displacement. Prior scholarship has principally examined the role of social belonging in social inclusion, mental health, and social cohesion. Bettez (Citation2010) underlines in their study of mixed-race women that belonging is a function of individual capacity to both self-identify and identify with other individuals. Cognitively, individuals derive their sense of belonging by cumulatively sharing experiences with a group; affectively, they process information to feel their shared experiences with the members of their community are meaningful and emblematic of their belonging to the group (Bollen & Hoyle, Citation1990). For Caxaj and Berman (Citation2010), attaining a sense of belonging is complex, but reflective of feeling positively connected to individuals with shared identities and similar contextual realities.

Social belonging is difficult to imagine without some of the vital values essential to a community, including shared trust, loyalty, grievances, and ultimately hope that the membership to the community will assist in addressing the members’ individual needs (Chavis et al., Citation1986). Several studies explored these relations within schools. Cueto et al. (Citation2010) asserts that social belonging in schools is impacted by peer-to-peer relationships and student-teacher interactions as well as the experiences of bias and discrimination while Finn (Citation1989) and Goodenow and Grady posit that social belonging is tied to a positive identification with and experiences within the educational institution that allow one to feel valued and respected. Hurtado and Carter (Citation1997) and Lee and Breen (Citation2007) view social belonging as a measure of connectedness and membership to one’s school or higher education institution. In essence, current literature points to the psychological, perceptual, physical, emotional, experiential, cognitive, and reciprocal nature of social belonging as a state, experience, process, and ultimately an innerdestination and feeling shaped by many factors, individuals, and institutional stakeholders.

Educational displacement model of radicalization

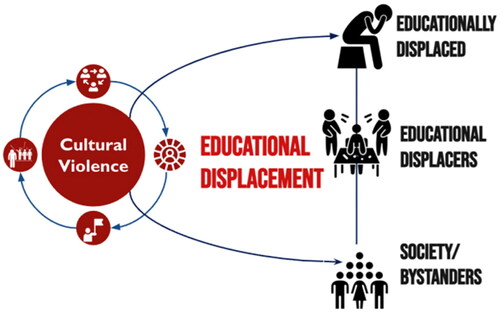

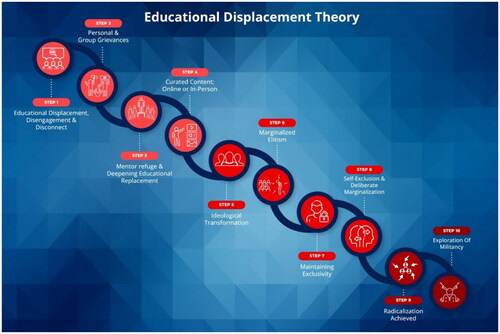

When social belonging is absent, individuals experience a sense of displacement from their community (). The initial feelings of isolation, invisibility, and loneliness emerge in the individual often due to the lack of kinship, friendship, and peer-to-peer acceptance creating a gulf between oneself and their immediate community. Sabic-El-Rayess (Citation2021) has shown that the cause of these initial feelings of isolation and disconnection may involve forms of alienation and exclusion targeted at this individual. These periods of marginalization and social exclusion prompt the individual to search for answers to this deepening displacement, often manifesting in the form of educational displacement (, Step 1), as it tends to be first observed in schools. As the individual sense of educational displacement increases, the role of the educator and the school continues to recede.

Figure 1. Educational displacement theory and model of radicalization. Source: Sabic-El-Rayess (Citation2021). How do people radicalize? International Journal of Educational Development, 87, 102499.

This Educational Displacement Model of Radicalization (Sabic-El-Rayess, Citation2023) first emerged from primary research with radicalized individuals in Europe. However, emergent and common across ideologies, geographies, and identities, a disconnection and lack of social belonging from mainstream society precipitates radicalization in the individual. The ten-step pathway () to radicalization offers a deeper understanding of the transformation that a radicalizing individual undergoes as they come into a new sense of self and adopt novel behaviors, beliefs, and values. As a person moves away into the margins of the society through lesser engagement in and from classrooms, schools, and workplaces, displacement and radicalization are further solidified.

As societal institutions and communities, particularly schools, fail to provide educational content that addresses a range of needs and engages individuals in educational spaces to create a sense of social belonging, the alternative content undermining formal education and institutions is likely to fill the void. Often, this process of displacement is exacerbated by Grievances (, Step 2), and the individual may begin to identify with other referential groups that they feel would share in their frustrations, displacement, and isolation. This research surveying students in 43 U.S. states has found that only 1% of students believe that all educators in their school can effectively handle the incidents of biased speech and behavior when they emerge, underlining the urgency of adequately training educators on links between bias, educational displacement, extremism, and violence prevention.

In searching for the cause of these grievances and the actors who can help address them, individuals find Mentor Refuge (, Step 3) in radicalizing recruiters who supply an answer to the cause of their grievance. By introducing a hateful narrative to shape the view of the grieving individual, the informal ‘mentors’ create the ‘Other’ in the minds of the individuals. The goal is to direct the resentment and anger of the grieving individual toward a group to escalate these feelings into violent expression. As Lauren Manning (Manning & Manning, Citation2021) recounts, in her telling of her own journey to and from extremism, ‘the recruiter referred to everyone outside of the movement as ‘sheep’, telling me it was good to be different.’

A replacement with alternative social spaces, alternative narratives, alternative information, and alternative experiences of connectedness with individuals within the extremist group, provides the contours of a new community and world to which one can belong. As the individual grows closer to the members in this alternative space, Curated Content (step 4) – in the form of lectures, podcasts, tutorials, social media posts, interactions, memes, and videos – projects blame for the grievances faced by the individual on a targeted group and links them to a larger narrative of hate. This targeted group becomes the object of hate that connects all the grieving individuals who experienced educational displacement. The school and the educators within it have been replaced. With the rise of artificial intelligence, social media, and digitally spread misinformation (Joshi & Sabic-El-Rayess, Citation2023), the internet has allowed individuals to group themselves into self-isolating clusters that radicalize and promote hate. Our surveying of students in 43 U.S. states has shown that only 15% of the participants learn what they wish in school and do not have a need to seek information outside school.

Throughout this gradual and complex process, the individual undergoes Ideological Transformation (, Step 5), disposes of their old self, and adopts a new mindset, worldview, behavior, and value set that justify violent expression as a method of addressing one’s grievances and fulfilling their sense of shared purpose with their referential extremist group. In other words, to escalate feelings of resentment and anger of the grieving individual into violent expression, ideological transformation is necessary. Curated content catalyzes the process by which an individual gradually surrenders an existing worldview or how they interpret the events in their life and society at large. Transformative learning theory (Mezirow, Citation1997) explains how an event or grievance in an individual’s life sparks transformative learning – a process in which an affected individual lets go of their old self and ‘constructs a new self to make sense of the world.’ (Sabic-El-Rayess, Citation2021) At this stage, the goal of the narrative of hate merges with the goal of the radicalized individual.

When Lauren Manning (Manning & Manning, Citation2021) reflects on her own experience of radicalization by saying: ‘I created an account educating myself everyday about how liberal whites were brainwashed…So this new knowledge made me feel we were better than they were’, she refers to Marginalized Elitism (, Step 6) in the Educational Displacement Model of Radicalization. Once the ideological transformation has been achieved, groups of individuals, who have accepted narratives of hate, develop a sense of elitism as a group of people who feel a sense of belonging. Possibly for the first time, they are empowered by hate and find a connection in their shared hatred toward a common target.

Having formed this marginalize elite, the members Maintain Exclusivity (, Step 7) by strictly associating with one another, listening to and taking direction from common sources of authority, and developing plans of action based on the information provided only by sources that reinforce their narratives of hate. To fully radicalize, the marginalized elite also engage in a process of self-enclosure, intensifying their exclusivity by restricting interaction from persons outside the group who think differently and do not subscribe to the narrative of hate they share. This step of Self-Exclusion and Deliberate Isolation (step 8) means going beyond the replacement of the educators and schools: the individuals cut ties with family, friends, and any influence from their ‘previous life’. At the next step in the process (, Step 9), the individuals have fully embraced the narrative of hate and the ideology motivating it. The final and tenth step of the Education Displacement Model of Radicalization is far beyond the capacity of educators and educational staff to address. Individuals at this stage of the pathway develop an openness to engage in violent expression against the targeted group. In research-based prevention efforts, we ought to be primarily concerned with the initial steps in the model, particularly Educational Displacement, which elevates the risk of exposure to extremist narratives and radicalization. The model also underlines that the initial steps provide the most opportune time and space for early prevention as educational displacement ought to be followed by the content, relationship, and community replacement to advance the person along the radicalization pathway. Therefore, the whole-of-school and particularly whole-of-school prevention approach at this early stage is a more pragmatic solution than deradicalization and intervention efforts after an individual has already and fully radicalized.

Methodology

Context

The survey was administered as part of Reimagine Resilience in order to inform the development of the curriculum. Reimagine Resilience is an innovative online training program designed for educators and education professionals to nurture resilience as an integral capacity in their students. This professional development program draws from Sabic-El-Rayess’ Educational Displacement Theory. This theory illustrates the ten phases that a student experiences on a pathway to violent expression. The program builds resilience to hate and violent expression by offering a training that amplifies protective factors – such as social connectedness, nonviolent problem solving, and forming cultures of prevention. Each training component advances prevention against every step on this pathway. Reimagine Resilience is housed at Columbia University’s Teachers College and was supported with an Innovation Grant awarded by the Department of Homeland Security’s Center for Prevention Programs and Partnerships (CP3).

Sampling and data collection

The data for the current study were drawn from an online survey administered by the authors to K-12 school and college students across the United States via the survey platform Qualtrics. Eligible for participation were all students being taught in U.S. schools and colleges at the time of data collection. The data were collected between March 15th and August 6th, 2022, to help inform the creation of Reimagine Resilience. Of the 301 students who took the survey, data of 208 was eligible in our data analyses, as 93 (Abdo, Citation2017) students did not fill out all of the questions of the survey requisite for the analysis. Our final sample thus included 208 students from 43 states across the U.S. Of those students, 33.7% identified as male, 63.9% as female, and 1.9% as non-binary. In terms of race and ethnicity, 53.8% identified as white, 15.9% as Black or African American, 13.5% as Asian, 16.8% indicated they were Hispanic, Middle Eastern, or of more than one race or ethnic group.

Measures

In this study, we are trying to quantitatively investigate which experiential and demographic factors might be risk – as well as protective factors of educational displacement. In addition to measuring educational displacement, we therefore collected multiple demographic predictors that might be related to educational displacement, a quantitative measure of experiences of bias and bullying in school, a measure of students’ relationship with their teachers as well as their confidence in their teachers being able to manage issues related to bias.

Educational displacement

We measure educational displacement as the lack of social belonging in school. Therefore, we employed multiple measures of social belonging in the school context. We adapted five social belonging items from the TIMSS questionnaire (e.g. I feel like I belong at this school; NCES, Citation2019), and added 10 items based on previous qualitative research on educational displacement. TIMSS is a series of assessments of mathematics and science knowledge from countries all over the world. It also includes measures of student belonging, which we adapted to also use in our survey. All social belonging items were answered on a 4-point scale (1 = disagree a lot, 4 = agree a lot). The Educational Displacement measure was calculated by standardizing the inverse of the mean over all items, reflecting the lack of social belonging. This measure was chosen so that a high value of educational displacement would correspond to a low value of social belonging. Taking the mean would ensure that our analysis was less susceptible to missing data in answers to single questions of the scale. McDonald’s ω= .96, reflecting a high reliability of the Educational Displacement measure. McDonald’s ω is a preferable measure of reliability than Cronbach’s alpha which is commonly reported in educational studies (Hayes & Coutts, 2020). It measures how much noise a measurement instrument produces. The closer the value to 1, the less the value of the instrument is dependent on measurement noise. The complete set of items including means, and standard deviations for each item can be found in Appendix A.

Experiences of bias

Experiences of bias were measured by asking the participants how often they have encountered one of the following types of discrimination either in person, over text, the phone, or on social media by other students at their school saying mean things about: (a) their physical appearance; (b) racial or ethnic background; (c) religion; (d) sexual orientation; (e) gender identity; (f) values or beliefs; and (g) immigrant background. The participants answered on a 5-point scale from (1 = never to 5 = daily). For the present research purposes, we computed a measure reflecting an ‘overall bias experience’ by calculating the standardized mean of the different encounters of biases so that a higher measure reflects experiencing more biases toward oneself. Given that McDonald’s ω= .72, there is an acceptable reliability of the overall experiences of bias measure.

Experiences of bullying

From the TIMSS (NCES, Citation2019), we adapted a measure of experiences of bullying in school. Participants had to indicate how often they have encountered one of the following behaviors from other students at their school toward themselves: (a) spread lies about them; (b) refused to talk to them; (c) said mean or hurtful things about them; (d) said mean or hurtful things to them; (e) threatened them; (f) physically hurt them; and g) excluded them from their group. The participants answered on a 5-point scale from (1 = never to 5 = daily). For the current study, we again computed an overall measure by taking and standardizing the mean of the different encounters of biases, so that a higher measure indicates greater personal exposure to bullying by other students. The McDonald’s ω= .84 shows a good reliability of the overall experiences of bullying measure.

Teacher relationship scale

In light of Sabic-El-Rayess (Citation2021) research on educational displacement, we developed a measure of a student’s relationship with their teachers, adopting also a part of Hoffman et al. (Citation2002) Social Belongingness Scale. The teacher relationship scale reflected whether students had at least one teacher at their school with whom they shared a mentorship relation (example item: I have at least one teacher at my school who I can confide in if I have a personal problem). It reflected whether students could ask teachers for their advice on academic, social, or issues of well-being. The scale consisted of eight items being answered on a 4-point scale (1 = disagree a lot, 4 = agree a lot). With McDonald’s ω= .84, we established good reliability of the overall teacher-as-mentor relationship measure.

Confidence in engaging with biases

Given prior research reviewed in the study, we assumed that one of the protective factors against biases is teachers’ capacity to engage effectively in addressing bias; so, we included a measure of the confidence that students had in their teachers of being able to manage biases well. The item asked the participants to indicate how confident they were that the teachers at their school could effectively mitigate and address biases at school (0 = not at all, to 10 = very much). This measure also captured how well teachers in a student’s school have dealt with biases in the past since students were likely to place more confidence in teachers who had effectively addressed prior issues of bias.

Demographic variables

We included multiple possible demographic predictors of educational displacement. In addition to questions concerning race and ethnicity, we also included a binary variable reflecting whether students participated in any extracurricular activities in or outside their school. We added students’ family income by asking participants whether they rated their family income as lower, similar, or better relative to the income of their peers’ families. By using a relative measure of income, we considered existing research in education that demonstrates students’ tendency to see poverty not as absolute, but rather as relative to the socioeconomic status of their peers in their educational settings (Sabic-El-Rayess & Otgonlkhagva, Citation2012; Sabic-El-Rayess et al., Citation2019).

Statistical analyses

This data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS 29, and we selected a significance level of α = .05 for all statistical analyses and computed two-tailed tests throughout. All continuous variables were winsorized before they were standardized. Winsorizing was done by inspecting boxplots of the variables and setting outliers (values above or below 1.5 times the interquartile range from the third and first quartile) to one value above or below the last non-outlier. Winsorizing is used to reduce the influence of outliers by changing the value of outliers to a more plausible value inside the boxplot. We chose winsorizing instead of excluding outliers to keep as much information about our participants as possible while mitigating the influence of outliers on our models. We investigated how educational displacement can be predicted in a multiple regression model, where a set of independent variables was used to predict educational displacement as the continuous dependent variable. Other than investigating which variables significantly predict educational displacement, multiple regression can be used to analyze how much variance in the dependent variable is explained by the independent variables. We chose a hierarchical multiple regression method to see whether a given set of independent variables predicts significant variance in the dependent variable before looking at the significance of the predictors themselves. It is critical to note here that multiple regression models do not provide any evidence of causal relationships. They merely investigate statistical relationships between variables.

The 95% confidence intervals were based on 5,000 bootstrap samples if not otherwise indicated. The method of bootstrapping is a resampling technique that involves repeatedly drawing random samples with replacements from the original data to create multiple simulated datasets. Through this procedure, one can get more robust confidence intervals that are not based on assumptions about the underlying distribution of the data. Zero-order correlations of all measures are presented in .

Table 1. Zero-order correlations between continuous variables.

Results

Demographic variables do not predict educational displacement

This study aims to identify potential risk, as well as protective factors of educational displacement, and the analysis aimed at identifying whether (1) identifying with a minoritized group is related to feelings of educational displacement; (2) experiencing bias influences feelings of Educational Displacement in school; and (3) a teacher-as-mentor relationship can help prevent Educational Displacement.

Furthermore, we wanted to test whether the introduction of certain variables, such as student’s own experiences with bias and harmful language explain significantly more variance in Educational Displacement than the demographic background of a student. This can be done by adding the variables in a later step in the hierarchical procedure and checking whether this significantly increases the explained variance in the dependent variable, that is, educational displacement.

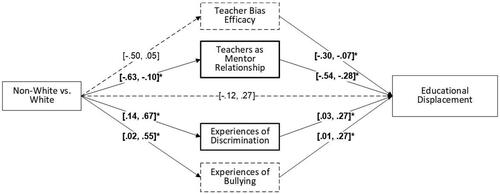

In the first step, we entered into the model the following demographic variables: race, ethnicity, family income, and extracurricular activities. The demographic variables explained a significant proportion of variance, R2 = .12, F(8, 199) = 3.47, p < .001. The only significant predictor of Educational Displacement, however, was perceived family income, β = −.61, SE = .17, t(205) = −3.75, p < .001, 95%-CI [-.92, −.30]. For all other coefficients and bootstrap intervals, see . This shows that, in terms of demographic variables, race, for instance, did not predict one’s lack of social belonging, but a student’s perception of lesser socioeconomic status in their school environment did.

Table 2. Regression coefficients of race, ethnicity, family income, activities inside and outside school, the ability of teachers to deal with issues of bias, experiences of discrimination and bullying, and a teacher as mentor relationship on educational displacement.

Experiential variables predict educational displacement

In the second step, we entered our standardized measures of overall experiences of bias and bullying, as well as the confidence students put in their teachers to handle issues of biases in their school well. This resulted in a significant change in the explained variance of educational displacement, indicating the model’s greater explanatory power, R2 = .33, F(3, 196) = 39.86, p < .001. All added variables significantly predicted Educational Displacement: Experiences of bias or bullying were associated with reports of higher educational displacement, whereas the students’ confidence in their teachers’ ability to deal with issues of bias was negatively associated with feelings of educational displacement. This finding indicates that it is the experience of bias and bullying in schools vis-à-vis one’s identity – rather than identity itself – that is significantly associated with the risk of Educational Displacement.

In the third step, we entered the Teacher Relationship Scale into the model. This again resulted in a significant change in explained variance in educational displacement, R2 = .09, F(1, 195) = 38.04, p < .001. A mentoring relationship with a teacher was negatively associated with feelings of Educational Displacement, β = −.40, SE = .07, t(205) = −6.17, p < .001, 95%-CI [−.54, −.25]. The finding confirms the importance of a student-teacher relationship in lessening Educational Displacement, and therefore minimizing the risk of radicalization and violent expression in schools. For all coefficients and confidence intervals of the third step-model, see .

White and non-white students differ in educational displacement in the U.S. context

In an additional analysis, we looked at the differences between white and nonwhite students regarding Educational Displacement, as well as the predictors of Educational Displacement. Instead of comparing Educational Displacement across all students of all races, we compared reported feelings of Educational Displacement between students who identified with the majority – i.e. white students – and people who identified with any one of the respective minorities, following an approach by Murphy and Zirkel (Citation2015). Whereas race itself was no significant predictor of Educational Displacement when races were entered separately into the model, being white or nonwhite was a significant predictor of Educational Displacement in that, nonwhite people reported higher Educational Displacement than white people, Welch t(205.91) = 2.70, p = .004, d = 0.37, 95%-CI [0.10, 0.62]. This result seemed to stem from the fact that nonwhite people reported more experiences of discrimination, t(206) = 2.97, p = .002, d = 0.41, 95%-CI [0.14, 0.67], as well as more experiences of bullying than white people, Welch t(205.41) = 2.12, p = .019, d = 0.29, 95%-CI [.02, 0.54]. This underlines the importance of this study’s key findings that race, religion, ethnicity, or other demographic markers are not predicting students’ sense of lacking belonging and increased displacement, but it is the cumulative effect of their experiences of harmful language and behavior directed at them by educators, peers, and educational staff that might adversely impact their sense of belonging and positionality in their schooling environment.

To investigate this relationship further, we additionally re-ran our multiple linear regression model with one binary variable reflecting whether a person was white or nonwhite, instead of including all races and ethnicities. Now, being white was a significant negative predictor of Educational Displacement in the first step of the model, β = −.30, SE = .13, t(205) = −2.31, p = .023, 95%-CI [−.55, −.05], in addition to family income, β = −.63, SE = .16, t(205) = −4.00, p < .001, 95%-CI [−.92, −.33]. Once the second-step variables such as experiences of bias, bullying, and confidence in teachers of managing issues of bias well were entered, however, being white was not a significant predictor of Educational Displacement anymore, β = −.09, SE = .11, t(205) = −0.83, p = .408, 95%-CI [-.29, .13].

This decrease in significance seemed to come from a mediation effect of experiences of bias, bullying, and the relationship between white students and the teachers at their schools. We investigated this relationship by running a mediation model in which race (white vs. nonwhite) served as independent variable (antecedent), student-teacher-relationship, experiences of bias and bullying, and confidence in teachers bias efficacy were entered as mediators, and educational displacement as criterion (consequent) using PROCESS 4.2 for SPSS (Model 4; Hayes, Citation2017). These mediation models can be used to investigate whether the influence of an independent variable (antecedent) on a dependent variable (consequent) can be explained by an indirect effect of the independent variable on a mediating variable (mediator). Following Hayes (Citation2017) recommendation against significance testing using Sobel tests, we bootstrapped the indirect and direct effects of belonging to a minority group on Educational Displacement. The student-teacher-relationship and experiences of bias served as significant mediators between race and Educational Displacement. Through having a poor teacher-student relationship, being nonwhite was associated with higher Educational Displacement, resulting in an indirect effect estimate = .15 (SE = .06), 95%-CI [.04, .28]. When encountering more experiences of bias, nonwhite students additionally reported higher Educational Displacement, estimate = .06 (SE = .03), 95%-CI [.01, .14]. Experiences of bullying and confidence in teachers managing issues of bias well were marginally non-significant, with estimate for bullying = .04 (SE = .03), 95%-CI [−.003, .12], and estimate for confidence in teachers’ bias efficacy = .04 (SE = .04), 95%-CI [−.005, .11]. These results indicate that nonwhite students reported suffering from educational displacement significantly more because they reported having a worse teacher-student-relationship and experiencing more incidents of bias. A full picture of the resulting mediation model can be found in . It is crucial to note that also for this analysis, no causality can be inferred from the results. While these results show an association between the experiences of bias and discrimination on educational displacement that seemed to be more frequent among minoritized students, experimental or quasi-experimental research would need to be conducted to establish causal effects.

Figure 2. Mediation model with race as antecedent, experiences of bias and bullying, teacher as mentor relationship, and teacher bias efficacy as mediators, and educational displacement as antecedent. Note. This figure shows 95%-Bootstrap-CIs of the regression coefficients between antecedent, mediators, and consequent. The path between the antecedent and consequent indicates the direct effect, i.e. the effect of race on educational displacement after the mediators are partialized out. Non-significant relations and non-significant mediators are marked with a dashed line. Nonwhite was coded as 1, white was coded as 0. All variables are standardized. The graph shows that Teacher-as-Mentor Relationships as well as experiences of discrimination significantly mediate the effect of identifying with a nonwhite group and reporting higher feelings of educational displacement.

Discussion

When there is a broader sense of educational displacement as this study finds amongst surveyed students in 43 U.S. states, the resulting disconnection in schools amplifies a collective risk for radicalization. Specifically, the study finds that the individual and societal risks for radicalization rise with the lack of effectiveness in schools in addressing biased speech and behaviors that target individuals based on their identity. When biased speech and behavior are inflicted upon a targeted, often a minoritized group, Educational displacement among youths emerges as an early warning sign of a principal risk factor for radicalization – both by the targeted groups and those enacting the targeting.

Individuals who are subjected to biased language and treatment without redress will experience feelings of educational displacement and isolation potentially prompting them to seek alternative spaces of belonging and possibly resort to violent means to cope with being discriminated against, targeted, ridiculed, othered, or ostracized (). In response, creating programs that build resilience to hateful and biased narratives by: (1) undermining the steps to the Educational Displacement Model of Radicalization and (2) raising awareness of educators and students around the adverse effects of Educational Displacement may prove preventative.

While the scope of this paper does not permit a more thorough analysis of Reimagine Resilience, a professional training program for educators that was informed by this research and designed by a team of researchers at Teachers College, Columbia University, with the help of an Innovation Grant through the Targeted Violence and Terrorism Prevention Program at the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Center for Prevention Programs and Partnerships, the study offers a model of how a professional training program can be informed by research to help enhance vital capacities amongst educators to, first, engage and reflect and then, integrate and apply newly acquired knowledge of a constellation of protective factors against violence and radicalization. The Reimagine Resilience program is structured using a novel protective and preventive resilience to hate framework uplifting self-awareness, community awareness, community belonging, management of grievances, media and digital literacy, critical thinking, community engagement, social connectedness, collective empathy, and allyship, and nonviolent problem solving to foster classroom culture of unity and resilience by dissembling educational displacement countenanced in institutional settings, practices, and curricula.

The enactors of biased behavior, harmful language, and bullying – whether students, educators, educational staff, or institutions – as our study shows, help normalize the displacement of targeted individuals and in doing so elevate their own risk for engaging in direct violence against the targeted group. Simply said, by engaging in displacing of the others, the displacers () themselves are at a heightened risk of normalizing violence, be it structural, direct or cultural (Galtung, Citation1990). Galtung’s early definition of cultural violence refers to the stories that dehumanize, bias, discriminate against others, or elevate one group’s supremacy over others, serving as the roots to direct violence. It is those stories that lead to Educational Displacement and ultimately its adverse effects. An act of killing or harming a human being for their identity is typically preceded or accompanied by the normalizing of the targeted group’s othering and dehumanization through mass media, education, and social and political narratives. Conversely, diverse and unifying storytelling, as a pedagogical approach, can be utilized as an effective tool to teach values, empathy, and community building and to transform mindsets. Additionally, bystanders who fail to act de facto contribute to this emerging culture of violence where bias renders direct violence against specific groups permissible.

It is critical therefore to underline that the adverse effects of Educational Displacement () of any one group in society adverse impacts all stakeholders. Therefore, this study and its findings help us converge toward one possible pathway to addressing Educational Displacement in American schools – building more effective and innovative professional training programs for educators and for students to uplift a shared sense of belonging across all racial, religious, and ethnic groups in the U.S. When educators and administrators fail to effectively address biased behaviors and speech in schools, this study confirms such failure of early prevention increases both societal and individual risks for radicalization and violent expression in the U.S.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

References

- Abdo, G. (2017). Like most Americans, U.S. Muslims concerned about extremism in the name of Islam. Pew Research Center.

- Alimahomed-Wilson, S. (2019). When the FBI knocks: Racialized state surveillance of Muslims. Critical Sociology, 45(6), 871–887. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920517750742

- Bettez, S. C. (2010). Mixed-race women and epistemologies of belonging. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, 31(1), 142–165.

- Bollen, K. A., & Hoyle, R. H. (1990). Perceived cohesion: A conceptual and empirical examination. Social Forces, 69(2), 479–504. https://doi.org/10.2307/2579670

- Caxaj, C. S., & Berman, H. (2010). Belonging among newcomer youths: Intersecting experiences of inclusion and exclusion. ANS. Advances in Nursing Science, 33(4), E17–E30. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANS.0b013e3181fb2f0f

- Chavis, D. M., Hogge, J. H., McMillan, D. W., & Wandersman, A. (1986). Sense of community through Brunswik’s lens: A first look. Journal of Community Psychology, 14(1), 24–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(198601)14:1<24::AID-JCOP2290140104>3.0.CO;2-P

- Cole, D., & Dempsey, J. (2006). Terrorism and the constitution: Sacrificing civil liberties in the name of national security. The New Press.

- Cueto, S., Guerrero, G., Sugimaru, C., & Zevallos, A. M. (2010). Sense of belonging and transition to high schools in Peru. International Journal of Educational Development, 30(3), 277–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.02.002

- DeWall, C. N., Maner, J. K., & Rouby, D. A. (2009). Social exclusion and early-stage interpersonal perception: Selective attention to signs of acceptance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(4), 729–741. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014634

- Finn, J. D. (1989). Withdrawing from school. Review of Educational Research, 59(2), 117–142. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543059002117

- Galtung, J. (1990). Cultural violence. Journal of Peace Research, 27(3), 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343390027003005

- Goodenow, C., & Grady, K. E. (1993). The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. The Journal of Experimental Education, 62(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.1993.9943831

- Hayes, A. F., & Coutts, J. J. (2020). Use omega rather than Cronbach’s alpha for estimating reliability. But…. Communication Methods and Measures, 14(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2020.1718629

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford.

- Herre, B., Ritchie, H., Samborska, V., Hasell, J., Mathieu, E., Roser, M. (2023). Terrorism. Our World in Data.

- Hoffman, M., Richmond, J., Morrow, J., & Salomone, K. (2002). Investigating “sense of belonging” in first-year college students. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 4(3), 227–256. https://doi.org/10.2190/DRYC-CXQ9-JQ8V-HT4V

- Hurtado, S., & Carter, D. F. (1997). Effects of college transition and perceptions of the campus racial climate on Latino college students’ sense of belonging. Sociology of Education, 70(4), 324–345. https://doi.org/10.2307/2673270

- Joshi, V. V. (2021). Book review: The cat i never named: A true story of love, war, and survival (2020) written by AmraSabic-El-Rayess and Laura L. Sullivan. New York: Bloomsbury. Global Journal of Peace Research and Praxis, 3(1), 1–6.

- Joshi, V., & Sabic-El-Rayess, A. (2023). Witnessing the pathways of misinformation, hate, and radicalization: A pedagogic response. In Education in the Age of Misinformation: Philosophical and Pedagogical Explorations (pp. 97–117). Springer International Publishing.

- Kearns, E. M., Betus, A. E., & Lemieux, A. F. (2019). Why do some terrorist attacks receive more media attention than others. Justice Quarterly, 36(6), 985–1022. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2018.1524507

- Lee, T., & Breen, L. (2007). Young people’s perceptions and experiences of leaving high school early: An exploration. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 17(5), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.887

- Manning, J., & Manning, L. (2021). Walking away from hate: Our journey through extremism. Tidewater Press.

- Martin-Gorski, D. (2002). Racial, religious, and gender profiling. Diss. SUNY Buffalo.

- Mezirow, J. (1997). Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 1997(74), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.7401

- Murphy, M. C., & Zirkel, S. (2015). Race and belonging in school: How anticipated and experienced belonging affect choice, persistence, and performance. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 117(12), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811511701204

- National Center for Education Studies. (2019). Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS). https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2022047

- Reimagine Resilience. (2023). Reimagine resilience at teachers college Columbia University, professional development program. https://reimagineresilience.org/

- Sabic-El-Rayess, A. (2011). Powerful friends: Educational corruption and elite creation in post-war Bosnia and Herzegovina. Research Brief.

- Sabic-El-Rayess, A. (2021). How do people radicalize? International Journal of Educational Development, 87, 102499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2021.102499

- Sabic-El-Rayess, A. (2023). Ending educational displacement. Bosnian Studies: Perspectives from an Emerging Field, 123.

- Sabic-El-Rayess, A., & Heyneman, S. P. (2020). Education and corruption.

- Sabic-El-Rayess, A., Mansur, N. N., Batkhuyag, B., & Otgonlkhagva, S. (2019). School uniform policy’s adverse impact on equity and access to schooling. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 50(8), 1122–1139. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2019.1579637

- Sabic-El-Rayess, A., & Marsick, V. (2021). Transformative learning and extremism. Actes de, 636.

- Sabic-El-Rayess, A., & Otgonlkhagva, S. (2012). School uniform cost reduction study: Standardization, simplification and supply policy.

- Sabic-El-Rayess, A., & Seeman, A. M. (2017). America’s familial tribalism.

- Selod, S., & Embrick, D. G. (2013). Racialization and Muslims: Situating the Muslim experience in race scholarship. Sociology Compass, 7(8), 644–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12057

- Tellmama. (2023). A decade of anti-Muslim hate. https://tellmamauk.org/a-decade-of-anti-muslim-hate/

Appendix A

Items of the educational displacement scale