ABSTRACT

The ivory trade is of global interest due to its impacts on elephant conservation. Thailand permits the domestic trade of ivory from domesticated elephants. Knowledge of the supply chain is important for managing this market in order to achieve sustainable benefits for both wildlife conservation and human livelihoods. We interviewed elephant owners and ivory manufacturers to conduct an analysis of the Thai ivory supply chain. Five key actor groups operate in this supply chain: elephant owners, intermediaries, manufacturers, retailers, and ivory consumers. Factors influencing the supply of raw ivory vary with harvesting, use, and sale destination but the financial needs of elephant owners and market factors are particularly influential. Elephant owner decisions also depend on elephant management, sentimental values, ivory beliefs, tusk forms, and legal awareness. These findings have the potential to inform the design of monitoring the Thai ivory market.

Introduction

The international trade in wildlife parts and products is of significant conservation concern. The global demand for ivory, for example, is considered to be a significant threat to African elephant populations (Loxodonta spp.) (Wittemyer et al., Citation2014). Such trade involves multiple actors at different levels of the supply chain. The illegal ivory trade involves a complex supply chain that includes elephant poachers in African countries, organized operations of local and national dealers to ship the raw materials, and consumers across multiple continents (Underwood et al., Citation2013; UNODC, Citation2020). These supply chain actors constitute a sophisticated network that ultimately facilitates, and perhaps drives, the operation of the illegal trade.

Both simple and complex relationships between supply chain actors also exist in the legal, domestic supply of wildlife parts and products. Supply chains in the bushmeat trade vary between animal species and contexts (Cowlishaw et al., Citation2005). These chains can begin with either commercial operators or farmer/hunters, before moving through a network of traders to consumers (Cowlishaw et al., Citation2005). Alternatively, the supply chain can be relatively simple with noncommercial hunters sourcing bushmeat for subsistence or local consumption (Cowlishaw et al., Citation2005; Delisle et al., Citation2018). Nondestructive consumption, such as in the vicuna (Vicuna vicuna) luxury wool trade, involve relationships between communities and herders, national and international manufacturers, exporters and traders (Kasterine & Lichtenstein, Citation2018). These types of legal trades in animal products can bring significant incomes to local communities, maintain traditional practices and values, as well as being of conservation benefit (Gordon, Citation2008).

Thailand permits a domestic trade in ivory from non-wild Asian elephants (Elephas maximus). Non-wild (hereafter domesticated) Thai elephants, are usually in private ownership, have been legally defined a draught animal since 1891 (Chaitae et al., Citation2022). Draught elephants have to be registered and regulated under of the Draught Animal Act (1939), whilst the usage and trade of tusks from these elephants are legal under the Elephant Ivory Act (Citation2015). Wild Asian and African elephants, and their constituent parts, are fully protected by the Wild Animal Reservation and Protection Act (2019) (Chaitae et al., Citation2022). The number of domesticated elephants is approximately 3,800, whereas wild Asian populations are estimated to total around 3,500 individuals in Thailand (Asian Elephant Range States Meeting Citation2017Final Report, 2017; Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation, Citation2020). Thai ivory-related laws prohibit international trade of ivory but enable the domestic trade of ivory from domesticated elephants via comprehensive controls to ensure that the trade operates without a negative impact on wild elephant populations. Knowledge of ivory supply is critical to evaluating the feasibility of a long-term legal market in Thailand. In this paper, we map the domestic, legal ivory supply chain, and conduct a supply chain analysis to explore factors influencing ivory supply.

Methods

Data Collection

Data were collected via 32 face-to-face semi-structured interviews and two telephone interviews with 23 elephant owners, and 11 ivory manufacturers. Our questions for the elephant owners were around decisions in tusk harvesting and uses e.g., how, and why tusks or parts thereof (hereafter tusks) of elephants were taken, how the tusks were used, and why and how they were sold. The ivory manufacturers were asked about tusk supply: their sources of raw tusks and how they were sourced. The interviews were conducted in Thai to facilitate understanding of the interviewees and their responses. The data were collected between November 2019 and February 2020 in different provinces in the North, Northeast, and South regions of Thailand ().

Participants were chosen using purposive and snowball sampling. The interviews began in the two main ivory manufacturing hotspots: Nakhon Sawan and Uthai Thani in the North, and Surin in the Northeast, based on the first author’s preexisting contacts. Additional elephant owner interviewees were referred by the interviewed participants, as well as local officers of the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation, and Department of Livestock Development. The interviews of elephant owners were carried out among groups of elephant owners living in the South, North and Northeast to cover variation among regions (). All participants gave verbal consent to be anonymously interviewed and audio recorded, as approved by the James Cook University Human Ethics Committee (H7873). Verbal consent was obtained due to a combination of poor literacy of potential participants, and potential hesitancy associated with the signing of documents. The interviews continued until data saturation was reached.

Table 1. General description of sampling areas related to ivory trade, see, for locations.

Analysis

All transcription were conducted in Thai to preserve the contextual meanings and perspectives of the interviewees. Quotations that are part of the Results are presented here in English. The translation of these quotations represents the meaning expressed by the participants for research validity (van Nes et al., Citation2010). Description and language amendments were put in square brackets to facilitate reading. Coding was conducted in English using NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd, Citation2018). We conducted open coding to enable a regeneration of concepts and category to refine the supply chain map and analysis of the supply chain.

Supply Chain Mapping

At the beginning of the study, we created a simple supply chain composed of three stages: source, manufacturing, and consumption, to guide data collection. To allow a more comprehensive understanding of the Thai ivory trade, we refined the supply chain using data from interviews with elephant owners and ivory manufactures, drawing on elements of grounded theory (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2015). Grounded theory uses empirical data to generate concepts and construct theories, thereby permitting interpretation and themes to be discovered within the data. As we focused on supply side information, the discussion in this study relates to the connections between elephant owners and ivory product manufacturers.

Supply Chain Analysis

As we employed open coding, different parts of each transcription were coded and marked with appropriate labels for identification during analysis (codes). The codes were grouped under the same category based on relationship and similarity. We created a conceptual model describing the process and drivers of ivory supply based on all categories and their relationships. Coding began with groups of elephant owners to set up initial concepts/categories based on their perceptions as supply sources. We later coded the data from ivory manufacturers and combined the codings of ivory manufacturers to those of elephant owners. This integration allowed data matching, and connected links between the two stakeholder groups. After generating an initial conceptual model, codes were then reworked to refine and validate the model.

Results

Thai Ivory Supply Chain Map

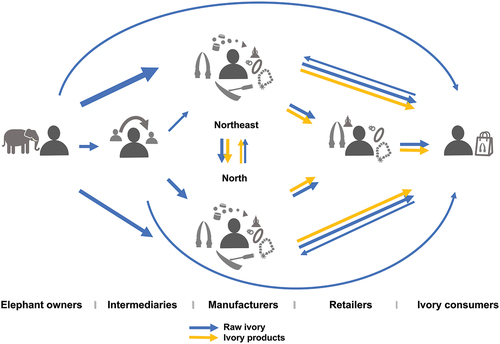

illustrates the supply chain of the Thai ivory trade, presented as supply chain actors engaged in the trade. The chain consists of activities of five key groups of supply chain actors: elephant owners, intermediaries, manufacturers, retailers, and ivory customers. Their roles and interactions in the supply chain have been presented in . Raw tusks enter the chain by direct transaction involving the elephant owners or via an intermediatory. Some tusks are purchased by users without the manufacturing step. These tusks are generally pairs of complete tusks, which are mostly used for decorative purposes.

Figure 2. The supply chain of the Thai ivory trade involves five supply chain actors: tusks harvested by elephant owners are passed to manufacturers either via direct trade between elephant owners and ivory manufacturers or via intermediaries, who are particularly important for manufacturers without access of local ivory e.g., manufacturers in Nakhon Sawan and Uthai Thani of the North. Finished ivory products are passed along the chain to final consumers through networks of manufacturers and retailers. While the flow of ivory from sources to consumers mostly involves monetary transactions, some elephant owners may transfer ivory to relatives and friends for in-kind and sentimental purposes. The width of the arrows represents the proportional volume of activities.

Table 2. Main supply chain actors and their interactions in the supply chain of Thai ivory trade.

Ivory manufacturers preferred to source ivory directly from elephant owners than from ivory possessors because of concerns about the certification of sources and ivory quality.

I choose to buy ivory recently cut or removed from elephants as I am quite sure this ivory is from domesticated elephants and have documents [certificate of ivory origin, movement permit etc]. That will not give me [legal] trouble. Also, old ivory is, sometimes, not good for making products … too dry and crack. (Ivory manufacturer 1)

Ivory products, such as jewelry or sacred items, are manufactured in two main areas: Surin in the Northeast, and Nakhon Sawan and Uthai Thani in the North. Manufacturers in Surin source tusks from Surin-based elephants that are either living locally or working in other areas. Raw tusks sourced from the South and the North have lower prices. Tusks from Southern owners are largely sold to Surin manufacturers; some are supplied to manufacturers in Nakhon Sawan. Tusks from Northern elephants mainly go to within-region manufacturers i.e. in Uthai Thani, Nakhon Sawan and Petchabun. Flows of tusks to manufacturers occur mainly through networks of elephant owners and prior contacts that elephant owners establish during their travels as illustrated by the following quote:

I brought my elephants to wander in different provinces [earning money from getting people to pay for the food of the elephant] when it was not prohibited. [From these travels] I [then] know many people. I sometimes gave my phone number to them. They can reach me when it is needed [regarding the sale of elephants or tusks]. Also, there are networks of elephant owners who work at [elephant] camps dispersed around the country. (Elephant owner 14).

Intermediaries are important supply chain actors for the trade of raw ivory, particularly in connecting sources with buyers from outside the area. Locals, either traders or (ex) elephant owners, take advantage of their knowledge of ivory availability within the area to gain extra income through facilitating ivory trades.

I bought tusks from either the South, Northeast or North. I myself do not know many elephant owners, but there are middlemen who know where elephant tusks will be cut. They are Surin locals who connect buyers with elephant owners. Surin elephant owners work countrywide. They are connected easily today using [social media platforms] Line and Facebook. (Ivory manufacturer 9)

Ivory manufacturers sell finished products to retailers countrywide. There are also transactions of both raw ivory and finished products between manufacturers in two regions. Northern manufacturers are known to be skilled at making elaborate carvings, while Northeast producers are considered capable in making products for the mass market. Manufacturing may involve work carried by freelance carvers and traditional jewelers. Domestic users purchase ivory items from manufacturers’ and retailers’ shops. Manufacturers also obtain raw ivory owned by processors or ivory consumers.

Supply Chain Analysis of Thai Ivory Trade

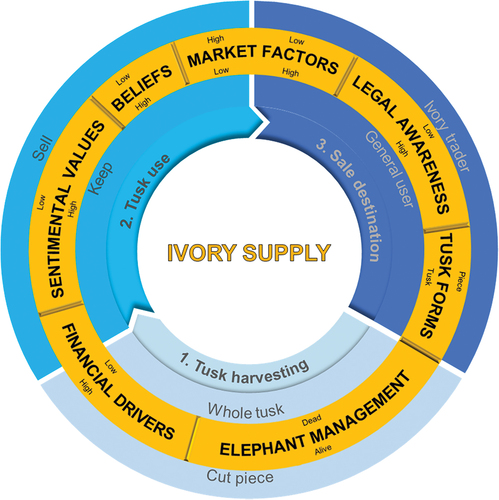

We found three steps in the decision making of elephant owners regarding selling ivory: tusk harvesting, tusk use and sale destination (). We discuss the influences on decision making at each stage of the supply chain in the following sections. In summary, ivory supply is significantly influenced by the financial needs of elephant owners and market factors. Elephant use and management, sentimental values, ivory beliefs, tusk forms, and legal awareness are secondary factors affecting decisions regarding the flow of ivory from elephant owners.

Figure 3. Ivory supply from elephant owners in Thailand is driven by multiple factors at each step. The financial needs of elephant owners have a strong effect on decisions related to tusk harvesting and use. Tusk use and sale destination are influenced by market factors (price and access). Other influences on ivory supply include elephant use and management, sentimental values, ivory beliefs, legal awareness and tusk forms.

Tusk Harvesting: A Common Practice in Elephant Domestication

To understand the start of the supply chain, we asked elephant owners how the tusks were sourced from elephants (Section 1 of ). Elephant owners cited two forms of ivory obtained from domesticated elephants: cut pieces and whole tusks, the choice of which is associated with elephant management practices and the financial needs of elephant owners.

Elephant Management

Whole tusks are removed from dead animals. In contrast, pieces of tusk are cut or trimmed throughout the lifespan of male elephants. All elephant owners emphasized that cutting tusks causes no harm to the elephants as illustrated by this response by a Surin elephant owner:

We cut tusks of the elephants at one-third of the length protruding out of the lip; this will not hurt animals. Cutting period cannot be fixed, [it] depends on tusk growth. Tusks grow about 3-10 cm a year. The growth rates are different among tusk types. Hin [stone] tusks grow slower than Yuak [banana trunk] and Wai [rattan] tusks. My 50 year-old elephant has Yuak tusks, which are now about 180 cm in length. I cut his tusks 4 times. I got about 80 cm pieces for the first cut, and later 50-60 cm pieces for each cut about every 5-6 years. No drug is needed during cutting, mahout controls the elephant while an elephant shaman cuts tusks. Only when the elephant dies, we get the whole tusks. (Elephant owner 4)

While a plan related to the whole tusks is needed only once the elephant dies, cutting throughout an elephant’s lifespan requires numerous decisions. As noted by an elephant owner:

A tusker without tusk cutting will earn more money from parading and show[ing their elephants] than if those tusks were cut because it looks much better [more powerful]. Elephant owners must choose to keep long tusks or cut tusks [for sale] to pay for necessities. (Elephant owner 6)

All groups of elephant owners refer to cutting or trimming the tusks of domesticated elephants as a long-established practice, which is necessary and commonly practised. They also mentioned that elephants were not only kept for the purpose of tusk supply:

I keep elephants because I love them, and no one keeps them for taking their tusks only. It is an extra [by-product] from having a tusker. (Elephant owner 7)

Surin elephant owners cut elephant tusks for elephant healthcare and safety, as well as to prevent the risk of injury to people who get too close to elephants. Trimming is normally not done on a regular schedule; rather, it is dependent on the growth of tusks and their maintenance needs (e.g., as a result of a tusk breaking):

[Tusk cutting] is [the main source of] livelihood for elephant keeping. We cannot avoid cutting if tusks are too long. Very long tusk elephants have difficulty in living, and it is dangerous for the surrounding people, and other elephants. Long tusks are heavy too. Elephants with crossed tusks cannot use their trunk well. Tusks also are worn out around trunk moving positions. Tusks grow continuously like nails. So if we don’t cut deep, there is not a problem. But the cuts that reach elephants’ tusk nerves causes infection. Cuttings, then, must be away from the nerve. After cutting, elephants feed better. Cuts in young males will increase the size of tusk bases. All do this, the first cut was done since the males are less than five-years old, depending on the rate of tusk growth which differ among individuals. If a tusk was broken, we mostly cut both tusks to make an equal size and [so it] looks good. (Elephant owner 2)

Besides the group of elephants belonging to Surin owners, there are elephants previously used in forest logging, before the 1989 logging ban, particularly in the North and South regions. The ex-logging elephants mostly work in elephant camps in tourism areas of the North and South regions. Some also are used as labor in logging operations in either rubber plantations or government forest plantations. The practice of cutting the tusks of laboring elephants is related to maintaining their working competence:

Southern males are still being used in logging, mostly in rubber plantations, not in the forests like before. Long-tusk elephants cannot work well and the tusks impede movement. Logging works involve lifting tree logs, which may crack or damage tusks. Very long tusks are more prone to be broken than short ones, similarly to long nails that are easily broken. The deep break causes blood loss and infection. Female elephants work in tourism. Elephant camps mostly use females, especially for ones that let tourists take care of elephants, not for riding. It is safe for tourists. (Elephant owner 17)

Financial Drivers

In addition to animal management, tusk cutting is expedited by the financial needs of elephant owners. Elephant owners in all three regions referred to the financial needs of both their family, and elephant upkeep, which was met by income from harvested tusks. A Surin elephant owner clearly reflected these factors in tusk harvesting:

I will again cut the tusks if the elephants have difficulties with it or I, myself, have a financial need. Most elephant owners today will not grow long tusks because it is worth money, needed for living. (Elephant owner 2)

Some elephant owners listed the following expenses as reasons for cutting the tusks of their elephants: livelihood expenses, including living expenses, school-related cost of family members, debt payment, vehicle purchase, as well as costs related to organizing traditional events such as religious ordinations and weddings. The cost of elephant food was stressed by most of the Surin elephant owners. The Surin mahouts related the increasing cost of elephant food to the decreased available area of elephant foraging areas, as this response of an elderly elephant owner illustrates:

Rearing an elephant today is impossible without cost. There were forests along Mun river where mahouts took elephants for wild foraging during day. We called elephants to go home at dark. So [we had] no cost of elephant food. Today, we cannot let elephants roam for food as areas are owned and crops are now cultivated. [There is] no place for elephants to forage, so we have to buy food for our elephants which costs us a lot of money. (Elephant owner 20)

The concern about the cost of food for captive elephants was illustrated by Elephant owner 2, who owns a male elephant:

There are many elephants at home today. We have problems with limited areas for keeping elephants and insufficient elephant food. Elephants are not allowed in reserved forests because they raid plants, even in some harvested rice fields as the field ridges are possibly damaged by the animals. The food problem is very tense during the dry season, we either source or buy the food from other provinces or regions which also costs us fuel. Elephant food in the dry season is mainly sugar cane plants, and crops after harvesting fruits such as banana, pineapple plants - not many choices. We pay for harvested banana plants, the whole plant, cut and brought back here by a truck. The monthly subsidy [subsidization from government to support elephant keeping] is not enough during the dry season [Feb-May] to provide a good volume of food for elephants. Other periods of the year are fine. [During the dry season,] I ordered a truck of pineapple plants from Rayong in the East for at least 20,000 Baht [c. USD 645] to share with other mahouts. It’s not affordable for me to pay all myself. We also grow Napier grass, but it can’t do well without water. (Elephant owner 2)

The financial needs of elephant owners have become an important driver for ivory harvesting as was described by these two interviewees with different financial backgrounds:

Villagers here [Surin] raise elephants for many generations and we keep elephants for our living. We are not rich. Cutting of ivory today almost relates to financial reason. Normal elephant owners like me cut tusks to meet the cost of living. Rich elephant owners don’t want to cut it, [they] want to grow it long, and get complete and long tusks once the animal dies and even refuse any buying offer. (Elephant owner 3)

I have about 20 elephants, eight of them are males. I pay mahouts for keeping all elephants. I only cut small pieces of the tusk tip, particularly, for five males having sharp-tip tusks which is dangerous for people. I think elephant owners don’t cut elephant tusks unless they have some troubles. Money trouble seems to be more for living life of mahouts todays. (Elephant owner 11)

Ivory Use: Decision Making Is Also Influenced by Financial Need

After obtaining tusks from elephants, about two-thirds of the elephant owners sell the tusks, whilst the remaining elephant owners use them for noncommercial reasons or gift (hereafter keep) the tusks. Noncommercial uses largely reflect the personal retention of tusks by the owner. A few interviewees mentioned giving tusks to relatives and friends without payment. Decisions about using the tusks is driven by the financial needs of elephant owners, market price, sentimental values, and ivory beliefs as outlined in Section 2 of .

Financial Drivers

Coincident with the harvesting step, financial factors play an important role in determining whether elephant owners keep or sell the tusks they harvest. About one third of elephant owners in our study choose to keep tusks. These elephant owners, in all three regions of Thailand, referred to their stable financial background and other important sources of income such as businesses e.g., owning elephant camps, and farming products such as rubber or oil palm. In contrast, financial factors are highly relevant to elephant owners whose livelihoods depend on keeping elephants, as described earlier by the Surin elephant owners. Most elephant owner participants sold the ivory they remove or cut from their elephants. The selling decisions were related to their financial needs and were largely aimed at the harvesting step as explained by a Surin elephant owner:

I wanted a truck for transporting my elephants. My son told me to cut tusks for selling and I did. I used this money, about 200,000 Baht [c. USD 6,450], for the down payment of this truck. (Elephant owner 6)

When a tusk is cut for selling, arrangements to sell the tusk are usually made in advance of cutting.

Most of the elephant owners here talk with local ivory shops about an incoming tusk cutting, if the shops want to buy tusks, and the prices they offer. I sold to the one with the highest price or sometimes I sold to the same buyer who bought my tusks before. When we, myself and tusk buyer, agree on the price, I cut the tusks. Buyers sometimes know about cutting from others, so they are the ones who contact me and give offers. (Elephant owner 9)

Market Price

Elephant owners refer to the increasing price of tusks because of increased market demand. This increase in price influenced their decision to sell:

Elephant owners, in early days, kept cut ivory for their children, relatives and friends; did not aim profit from tusks. At that time, ivory price was low or even unable to sell. Later, there were buying offers for tusks with a high price so elephant owners can earn good money from selling tusks. (Elephant owner 11)

Some selling is also delayed until the ivory price is higher.

Southerner [Southern elephant owners] mostly kept ivory, they may sell them later when getting a high price, gaining good profit” (Elephant owner 22)

Most elephant owners also related the increase of Thai ivory price to the legal reform in 2015 which prohibits entry of African ivory into Thai market such as:

Having law is good, it brings up price of legal tusks. (Elephant owner 3)

[There is] no foreign, cheap, tusks now, only Thai tusks, so we can sell our tusks at a very good price. (Elephant owner 18)

Elephant owners normally earn incomes ranging from 25,000–45,000 Baht (approximately USD 800–1,450) per kilogram for cut pieces (Bank of Thailand, Citation2019). The value of a pair of complete tusks is higher than for cut pieces; the value reflects not only weight, but also the shape and other physical characteristics of the ivory. The reputation of the elephant also influences tusk price. Cut pieces from a popular tusker were sold for up to three times higher than other elephants’ tusks.

I could get millions of Baht from selling a whole pair of ivory from my elephant if the animal dies. That money might buy me two elephants. This elephant has very long tusks. He has been filmed many times, he is quite well-known. I once offered his cut pieces of tusks to a Royal family member. His tusks are wanted by anyone. Ivory traders [Manufacturers] here paid me 60,000 Baht [c. USD 1,935] a kilo during 2015-2016, so they got these tusks for making items. (Elephant owner 4)

Sentimental Values

Elephant owners who desired to keep tusks described the sentimental values of tusks including the pride of the owners of the elephants, remembrance of family members, family inheritance, and mahout-elephant bond. The transactions of tusks from elephant owners to users e.g., family members, relatives, friends, generally do not involve monetary exchange.

I mostly keep the tusks and give some to my relatives. My family has elephants, so we should have elephant tusks for remembrance. I do not have a money issue, and do not think of selling the tusks, want to keep them, it is valuable to my feeling. Friends also asked for ivory pieces for making ivory items for their uses, I also gave some to them. (Elephant owner 17)

I myself share ivory with my siblings and I want them to keep it. My father had 5-6 elephants and later was killed by an elephant. Our family had been insulted about keeping inherited elephants after father died. I have proved that I can take care of all father’s elephants. Ivory of elephant has sentimental values for me to remember my father who took care of our family with income from elephant uses. (Elephant owner 22)

Beliefs

Beliefs in the protection and propitious properties of ivory were mentioned by most elephant owners. A naturally broken piece is sought after by believers, a reason for keeping tusk pieces:

Elephant owners normally sell cut pieces, but we want to keep broken pieces because it is naturally cracked, not an exploit. It does not happen frequently, so it is sacred. This protects us from bad things. Even today, people seek for these. If elephants do not want to give these pieces to anyone, no one finds those breaks, even if they seek hard. (Elephant owner 12)

One elephant owner revealed his desire to keep tusks, even though that was likely to be impossible given his current financial position:

I thought that would be good if I could keep the tusks. If there were no financial problem, I would keep tusks to inherit [to my] children. Rich elephant owners keep a lot of tusks from either their own elephants or buying from others who need money. (Elephant owner 6)

Sale Destination: Ivory Cuttings to Manufacturers

The final factor affecting ivory supply is the sale destination (Section 3, ). When asking further about tusk buyers, most elephant owners that were interviewed referred to ivory manufacturers (traders) as the most frequent destinations for cut pieces. Some Surin elephant owners sell whole tusks to general users. Factors influencing sale destination include market access, legal awareness of elephant owners, and the form of the tusk.

Market Access

When compared with elephant owners in the North and South regions, Surin elephant owners have the advantage of ready access to local ivory manufacturers. The reputation of the Surin elephant village in Thatum also offers the opportunity for connecting with external markets (either general users or ivory traders). Elephant owners also sell their tusks to external markets to gain a higher price.

I will get better price if a buyer is from Bangkok. We can do delivery for them. My son got about four million Baht from selling four pairs of tusks. They were all completed tusks. I like to keep tusks long and remove tusks once the elephant dies because I get more money, and these tusks also can be sold to general buyers. (Elephant owner 8)

Communication about ivory cutting is initially by word of mouth and then spread to external buyers via intermediaries. The prevalence of social media provides an additional tool for advertising harvested tusks to a wider market.

Cutting of tusks news is well spread among locals. Buyers are both ivory traders and rich locals. Outsiders [buyers from outside of the area] know from locals who is also a middleman. Some also posted in Facebook or Line that there is a legal ivory cutting. So interested people can contact them. (Elephant owner 9)

Ta-klang elephant village in Thatum of Surin is well known countrywide as the home of domesticated elephants. The village has been promoted for tourism by local authorities, and the national government. There are hundreds of elephants living within the village and these animals are a potential source of ivory for general users and attract ivory buyers. Thus, elephant owners can demand a premium price. This fact was reflected by Surin ivory manufacturers who seek a lower cost for ivory from other regions.

Elephant owners here (Surin) sell tusks with a high price. Surin is famous about elephants, and there are ivory manufacturers. I bought raw tusks from this village [Ta-klang] and areas nearby 4-5 times, then later I sourced from other areas through group of elephant mahouts. I mostly now buy raw tusks from the South. (Ivory manufacturer 3)

In contrast to the Surin tusk market, tusks from the South and North have limited access to the general market. Elephants are dispersed across regions and these areas are less known for elephant husbandry compared with Surin. Southern and Northern elephant owners tend to sell the tusks to ivory manufacturers using their established elephant-related networks.

I sold tusks to a Surin trader who I knew for a long time. Surin people might know me because I bought a Surin elephant at a high price. We gather cut pieces until it is much enough to sell. The trader asked me to source tusks from around here [South] for him too. My friend got 350,000 Baht [c. USD 11,300] for about 10 kilogram of cut pieces. (Elephant owner 18)

There are many elephants in the North. Elephant owners know each other both within and outside the region. We know others since we looked for an elephant to buy. I sold my tusks to the same ivory trader in the North. When other elephant owners asked me where to sell the tusks, I also suggested the ones I knew. I now source tusks to supply an ivory manufacturer in the North. (Elephant owner 6)

I bought tusk from everywhere both local and other provinces and regions. I rarely buy tusks from the South. Tusks in my shop are mostly from the North, for example, Nan, Phrae, which is closer. People know I have an ivory shop, and buy their elephant tusks. They further tell elephant owners or people want to sell tusk to sell tusks to me. It’s hard to find general buyers; they don’t know who wants tusks. Also buyers, themselves, have no idea where to get tusks, except from ivory shops and Surin. (Ivory manufacturer 14)

Legal Awareness

We asked participants about the legal requirements related to tusk-supply activities, including sales. Their responses demonstrated variable legal understanding. This variability influences decisions on sale destination; elephant owners with limited legal awareness chose to sell tusks to authorized ivory manufacturers, rather than general users, to avoid legal difficulties. Manufacturers are better educated about legal requirements than are elephant owners. The legal awareness of elephant owners varies both between and within regions. Surin elephant owners are mostly aware of the legal provisions related to the cutting of tusks, whilst North and South elephant owners generally are confused about the complicated requirements of ivory registration. The manufacturers facilitate the operations of elephant owners who lack legal understanding of the arrangements required to complete legal requirements e.g., by offering transport to ivory registration offices, and assistance with consultations with relevant officers.

I do not know details about the ivory-related law. I sold tusks only to local ivory shops here (Surin) where they arranged all [the paperwork] for me. (Elephant owner 2)

Transfer of tusks will be done at a forestry [Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation] office. If selling to Surin [ivory] traders, they know very well about legal procedures. They liaise with authorities which is easy for me. Before having the law, we did not have to inform the government, only used an elephant identification document. (Elephant owner 18)

Some elephant owners in the South do not know the law because they do logging in remote areas. I spend a week both for traveling and arranging tusks buying there. Even if it is very far from here, the tusks are much cheaper. They [the prices] are also negotiable. (Ivory manufacturer 3)

A lack of legal awareness amongst general users likely narrows the available market for elephant owners as explained by a Surin ivory manufacturer:

Today, there are not many raw ivory buyers [general buyers] that directly get tusks from elephant owners. General buyers are afraid of buying it because they are unsure about laws. Elephant owners then have to sell the tusks to us [manufacturers]. (Ivory manufacturer 4)

Tusk Forms

Tusk form (cut pieces or whole tusks) also determines buyer group. General users normally seek a pair of complete tusks with sharp tips for decorative purposes. Cut pieces are largely destined for ivory manufacturers. As this elephant owner explained:

Cut piece are mostly sold to ivory shops [manufacturers], not sold for use as decorative tusks because there is no tusk cavity, [they are] not complete and big. Tusks that people use for decoration are those that were removed from a dead elephant. (Elephant owner 2)

Manufacturers also bought whole tusks. Suitable ivory items can be manufactured in response to tusk size and sharp. A larger size is preferable. For example, a 3.5-inch diameter piece can produce bangles that would pay back the material cost.

Discussion

Thai Ivory Supply Chain

Supply studies can be beneficial for the management of the wildlife trade. Studies of the bushmeat supply chain, for example, have recommended comprehensive monitoring and management of the trade at all steps along the chain (Boakye et al., Citation2016; Cowlishaw et al., Citation2005). Additionally, studies have found that the bushmeat market is driven by supply, thus policy effort to reduce hunting would likely decrease the market overall (McNamara et al., Citation2016). An analysis of the illegal ivory chain provided a comprehensive understanding of the trade to assist countries in designing appropriate policy responses (UNODC, Citation2020). The structure and mechanism of the chain would guide enforcement actions to be more specific to relevant actors in source countries, while consumption nations should tailor suitable prevention measures around ivory smuggling.

The legal ivory market is controversial due to its potential to mask the laundering of the illegal supply (Bennett, Citation2015). For this reason, comprehensive controls of the market are needed to ensure that only legal products enter the supply chain. The supply chain of ivory includes different actors who facilitate the flow of traded items to end users (UNODC, Citation2020). Understanding the role and function of these supply chain actors will assist in trade monitoring.

We identified key actors in the supply chain, and their interactions along the chain. A comprehensive monitoring plan would target these actors. In theory, with stable demand the availability of illegal stock should decrease the price of Thai ivory. Regular observation of the raw ivory volume flowing into manufacture, and the market price, would flag possible market change, as well as indicate the possibility of illegal stock within the market. The input volume of tusks from existing registered stock or ivory consumers to the manufacturing process should not be missed as this will be a surplus to the chain in addition to newly harvested tusks.

Legal Ivory from Elephant Domestication

A substantial proportion of the raw tusks supplied to the ivory market comes from the management of domesticated elephants. Dead animals provide one set of whole tusks (Phuangkum et al., Citation2005), while live domesticated elephants can provide tusk pieces on multiple occasions during an animal’s life. Tusk length depends on tusk use and wear rate, as well as tusk growth rate (Sukumar, Citation2003). Wild elephants use tusks to collect food etc., which results in natural shortening of the tusk via wears and cracks (Vanapithak, Citation1995). Oversize tusks can impact the elephant’s quality of life (Sukumar, Citation2003), therefore cutting tusks in domesticated elephants is necessary for elephant healthcare, human safety and work competence. Tusk cutting is common practice in elephant domestication and conducted in non-lethal manner in contrast to tusks obtained from wild elephants, including African elephants.

Decision making in relation to ivory supply, harvesting and selling of elephant tusks, is largely driven by the financial needs of elephant owners, in particular mahout elephant owners who are the majority of elephant owners. A study of domesticated elephants in the Northern tourism industry reported that almost 40% were owned by mahouts, followed by camp owners, and non-mahout owners, respectively (Godfrey & Kongmuang, Citation2009). In our study, most of the elephant owners were mahouts in an uncertain financial situation, who used the extra income from selling elephant tusks to meet their household and elephant keeping costs. Thailand’s tourism industry, from which most elephant owners gain incomes has been heavily impacted by the COVID pandemic (”COVID 19 pandemic causes many elephants unemployed,” Citation2021, Thai Elephant Alliance Association, Citation2021). As such, the financial problems of many elephant owners are likely to have increased.

The decision to sell tusks is also affected by their market price. Keeping raw tusks for later sale, at a higher price, is an option for some elephant owners as ivory can be treated as an investment due to its durability and minimal storage costs (Moyle, Citation2014). Legality is also a significant determinant of ivory market price (Sosnowski et al., Citation2019); the high value of ivory is a consequence of the 2015 legislation reform. This restriction reduced the potential ivory supply and increased the price of tradable stock (legal ivory). A similar change in the price of raw ivory was also reported in Japan after the international ivory ban (Menon & Kumar, Citation1998).

As the illegal trade impacts the survival of elephants and violates CITES; CITES recommends that the domestic market, which may contribute to elephant poaching or the illegal ivory trade, be closed as a matter of urgency (CITES, Citation2019). This action would pose potential risks to the livelihoods of Thai elephant owners, as well as actors along its supply chain. Our research also revealed the positive attitudes of elephant owners to legislation deterring the entry of illegal ivory that has resulted in the high price of legal ivory in Thailand. This economic incentive should result in elephant owners, who directly benefit from the robust legal measures and existence of the domestic legal market, complying with the relevant Thai laws.

Conclusion

In Thailand, domesticated Asian elephants are classified as draught or working animals; their tusks and other parts are thus viewed as by-products of elephant domestication. The legal ivory trade is clearly beneficial to Thai elephant owners, particularly for the mahout owners who earn their living from keeping elephants. Selling tusks is increasing through time, likely due to increased financial pressures on elephant owners’ and market factors that increase the price of raw ivory. Comprehensive control of the domestic trade in ivory from Thai domesticated elephants is required to prevent the entry of illegal supply from African and other Asian elephant sources. A practical technique for distinguishing sources of ivory has recently been developed that has the potential to strengthen enforcement (Chaitae et al., Citation2021). Monitoring the supply chain would also provide valuable information on changes in supply and identify further needs for investigation and enforcement. Legal awareness among groups of the supply chain actors is crucial for enhancing compliance for the whole supply chain. For instance, groups of elephant owners need to be educated about the control. The legal knowledge of intermediaries, taking roles as information breakers, should promote legal transactions of ivory. These initiatives would not only improve livelihood profits, but benefit conservation by minimizing the non-detrimental effects on the survival of other elephant populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to thank the Thai government for sponsoring the first author’s PhD at James Cook University. We are grateful to C. Thongpim, B. Thaidham, K, Chansa-nga and P. Ketkeaw for assisting with participant recruitment. Our special thanks to A. Niyomsub for help in with data collecting, and C. Brown for commencing on a draft of the manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

The first author is an officer in Thailand's Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation. The other authors have no potential competing interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Asian elephant range states meeting 2017 final report. (2017). 2017 Asian Elephant Range States Meeting. https://elephantconservation.org/iefImages/2018/03/AsERSM-2017_Final-Report.pdf

- Bank of Thailand. (2019). Foreign exchange rates for annual period 2019. Retrieved June 28, 2022, from https://www.bot.or.th/App/BTWS_STAT/statistics/ReportPage.aspx?reportID=123&language=eng

- Bennett, E. L. (2015). Legal ivory trade in a corrupt world and its impact on African elephant populations. Conservation Biology, 29(1), 54–60. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24481576

- Boakye, M. K., Kotzé, A., Dalton, D. L., & Jansen, R. (2016). Unravelling the Pangolin Bushmeat Commodity Chain and the Extent of Trade in Ghana. Human Ecology, 44(2), 257–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-016-9813-1

- Chaitae, A., Gordon, I. J., Addison, J., & Marsh, H. (2022). Protection of elephants and sustainable use of ivory in Thailand. Oryx, 56(4), 601–608. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605321000077

- Chaitae, A., Rittiron, R., Gordon, I. J., Marsh, H., Addison, J., Pochanagone, S., & Suttanon, N. (2021). Shining NIR light on ivory: A practical enforcement tool for elephant ivory identification. Conservation Science and Practice, 3(9), e486. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.486

- Chomdee, A., Oadjessada, P., Submak, M., Saendee, B., Lem-ek, S., Chanpoom, C., & Hongthong, D. (2013). Folk Gajasastra inherited wisdom of the Kui in Surin province. Ministry of culture. http://ich.culture.go.th/index.php/en/research/497–m-s

- Chotikasemkul, N. (2019, May 6). Trang held the largest encouragement ceremony in the south for elephants with arrangement of two-ton elephant food. 77Koaded. https://www.77kaoded.com/news/nopparat-chotikasemkul/482884

- CITES. (2019). Conf. 10.10 (Rev. CoP18): Trade in elephant specimens. Retrieved October 12, 2021, from cites.org/sites/default/files/document/E-Res-10-10-R18.pdf

- Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. L. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th) ed.). SAGE.

- COVID 19 pandemic causes many elephants unemployed. (2021, July 14. Siamrath. https://siamrath.co.th/n/261706

- Cowlishaw, G., Mendelson, S., & Rowcliffe, J. M. (2005). Structure and operation of a Bushmeat Commodity Chain in Southwestern Ghana. Conservation Biology, 19(1), 139–149. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3591017

- Delisle, A., Kiatkoski Kim, M., Stoeckl, N., Watkin Lui, F., & Marsh, H. (2018). The socio-cultural benefits and costs of the traditional hunting of dugongs Dugong dugon and green turtles Chelonia mydas in Torres Strait, Australia. Oryx, 52(2), 250–261. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605317001466

- Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation. (2020, March 13). Conservation of wild Asian elephants updated on Thai Elephant Day 2020. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/prhotnews02/posts/2109867205825421

- Deputy commissioner-general visited the city of elephant for inspecting ivory businesses. (2016, August 23). Siamrath. https://siamrath.co.th/n/1740

- Elephants from the North and the Northeast increasingly moved to the South to support tourism and labour uses. (2017, March 13). Thairath News. https://www.thairath.co.th/news/local/south/883021

- Godfrey, A., & Kongmuang, C. (2009). Distribution, demography and basic husbandry of the Asian Elephant in the tourism industry in Northern Thailand. Gajah, 30(2009), 13–18. https://www.asesg.org/PDFfiles/Gajah/30-13-Godfrey.pdf.

- Gordon, I. J. (2008). The Vicuna: The theory and practice of community based wildlife management. Springer.

- Kasterine, A., & Lichtenstein, G. (2018). Trade in Vicuña: The implications for conservation and rural livelihoods (No. Report No. SIVC-18.13.E). International Trade Centre. https://www.intracen.org/uploadedFiles/intracenorg/Content/Publications/Vicuna_trade_final_Low-res.pdf

- Krishnasamy, K., Milliken, T., & Savini, C. (2016). In transition: Bangkok’s Ivory market—An 18-month survey of Bangkok’s Ivory market. TRAFFIC Southeast Asia Regional Office. https://www.traffic.org/site/assets/files/3683/traffic-report-bangkok-ivory.pdf

- McNamara, J., Rowcliffe, M., Cowlishaw, G., Alexander, J. S., Ntiamoa-Baidu, Y., Brenya, A., & Milner-Gulland, E. J. (2016). Characterising wildlife trade market supply-demand dynamics. PLOS ONE, 11(9), e0162972. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0162972

- Menon, V., & Kumar, A. (1998). Signed and sealed: The fate of the Asian elephant (No. Technical Report No. 5). Asian Elephant Research and Conservation Centre. http://www.wpsi-india.org/images/signed_and_sealed.pdf

- Moyle, B. (2014). The raw and the carved: Shipping costs and ivory smuggling. Ecological Economics, 107, 259–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.09.001

- Phuangkum, P., Lair, R. C., & Angkawanith, T. (2005). Elephant care manual for mahouts and camp managers. FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific.

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2018). NVivo (Version 12) [Computer software]. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- Sosnowski, M. C., Knowles, T. G., Takahashi, T., & Rooney, N. J. (2019). Global ivory market prices since the 1989 CITES ban. Biological Conservation, 237, 392–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.07.020

- Stiles, D. (2003, August 14). Ivory carving in Thailand. Retrieved October 10, 2021, from asianart.com/articles/thai-ivory/index.html#008

- Sukumar, R. (2003). The living elephants: Evolutionary ecology, behavior, and conservation. Oxford University Press.

- Thai Elephant Alliance Association. (2021). Walking through COVID with elephants. Retrieved October 17, 2021, from https://www.thaielephantalliance.org/

- Tipprasert, P. (2002). Elephants and ecotourism in Thailand (Giants on our Hands). Proceedings of the International Workshop on the Domesticated Asian Elephant. Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific.

- Underwood, F. M., Burn, R. W., & Milliken, T. (2013). Dissecting the illegal ivory trade: An analysis of ivory seizures data. PLOS ONE, 8(10), e76539. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0076539

- UNODC. (2020). Supply and value chains and illicit financial flows from the trade in ivory and rhinoceros horn (World Wildlife Crime Report: Trafficking in Protected Species, 107–132. United Nations. https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/wildlife/2020/WWLC20_Chapter_8_Value_chains.pdf

- Vanapithak, P. (1995). Elephants and elephant-related laws. Royal Forest Department.

- van Nes, F., Abma, T., Jonsson, H., & Deeg, D. (2010). Language differences in qualitative research: Is meaning lost in translation? European Journal of Ageing, 7(4), 313–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-010-0168-y

- Wittemyer, G., Northrup, J. M., Blanc, J., Douglas-Hamilton, I., Omondi, P., & Burnham, K. P. (2014). Illegal killing for ivory drives global decline in African elephants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(36), 13117–13121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1403984111