ABSTRACT

Fishing is part of human culture since ancient times to catch fish. The use of live bait by anglers is an important factor in the spread of invasive aquatic species. To analyze the habits of Indonesian anglers in using freshwater crayfish as live bait, an anonymous online questionnaire was spread via social media in Indonesia. The questionnaire included a series of closed and open-ended questions that investigated various socio-psychological parameters and types of bait used by Indonesian anglers. Redclaw crayfish Cherax quadricarinatus, which is non-indigenous in most of the Indonesian territory, was found to be used by 13% of anglers for this purpose there. These findings illustrate the need for focused management activities. Any potentially invasive non-native species imported into Indonesia, as well as those that are accidentally or deliberately released into the waters, should be regulated, so as not to cause environmental damage.

Introduction

Fishing activities have been known to the world community for thousands of years (Rochet, Citation1998; Sahrhage & Lundbeck, Citation1992). In the beginning, fishing was a foraging activity, and it even became a livelihood for some people (Bērziņš, Citation2010; Fišáková et al., Citation2014). It also pleasured the anglers (Sahrhage & Lundbeck, Citation1992), and nowadays it is an alternative recreation and sport for many enthusiasts (Cooke & Cowx, Citation2004; Cowx, Citation2002; Oh et al., Citation2013). Angling as a part of fishing is a popular hobby worldwide (Hancz, Citation2020). The total number of active anglers was estimated to being up to 700 million people worldwide (Skrzypczak & Karpiński, Citation2020).

Most Indonesian people from various backgrounds like fishing in general and angling in particular (Fitriani et al., Citation2019). The Indonesian archipelago consists of more than 17,000 islands, has about 370 ethnic groups and is located in Southeast Asia, with a very complex habitat type and geological history (de Bruyn et al., Citation2014; Persoon & van Weerd, Citation2006). Ecological adaptation due to biogeographic, ecological, geological, and climatic factors has led to the evolution of megadiverse flora and fauna with a large number of endemic species (Lohman et al., Citation2011). Indonesia has an official organization recognized by the government, namely the Indonesian Sport Fishing Federation (FORMASI). Fishing can be done in almost all public waters such as brooks, rivers, lakes, reservoirs, swamps, fishing ponds, and the sea (Anderson, Citation1982; Ball & Tousignant, Citation1996; Carpenter & Brock, Citation2004; Fagan, Citation2017; Nadler et al., Citation2013; Vaughan & Russell, Citation1982). The species of fish caught vary widely according to the area and habitat where fishing activities are carried out. Non-native species are also exploited by this activity, such as giant arapaima Arapaima gigas (Marková et al., Citation2020) and Amazon sailfin catfish Pterygoplichthys disjunctivus and P. pardalis (Patoka et al., Citation2020).

In Indonesia, almost all provinces exploit waters as a natural food-producing environment. Likewise, the tribes in Indonesia carry out fishing activities which have become one of the cultures as a source of livelihood, economy, and activities to make a living (Muawanah et al., Citation2018; Purwanto, Citation2018; Rostitawati et al., Citation2019; Salas & Gaertner, Citation2004). Along with the times, the popularity of fishing activities has increased in the community. The increasingly varied motivation of anglers has led to the development of different fishing activities, which are not only carried out for economic activities but also as entertainment, sports, hobbies, and competitions (Arlinghaus et al., Citation2015; Bakker et al., Citation2013; Darmanin & Vella, Citation2018; Hummel, Citation1994; McIntosh, Citation2011; Pitcher & Hollingworth, Citation2002).

A very important factor in fishing activity is artificial or live bait use affecting the attraction and stimulation of target fishes (Kilian et al., Citation2012). Even if known consequences such as a vector of biological invasions (Goodchild, Citation2000; Zeng et al., Citation2015) have led to a ban in several countries (Olden et al., Citation2006), live crayfish use as bait is legal elsewhere including in Indonesia (Kilian et al., Citation2012).

Indonesia has native crayfish species from the single genus Cherax such as Cherax acherontis, C. gherardii, C. holthuisi, C. pulcher and related species native to the western part of New Guinea (Bláha et al., Citation2016; Lukhaup, Citation2015; Lukhaup & Pekny, Citation2006; Patoka et al., Citation2015, Citation2017). These species are not cultured for the ornamental trade or human consumption but are collected exclusively from the wild while C. quadricarinatus and North American Procambarus clarkii are produced in aquaculture (Patoka et al., Citation2018a; Putra et al., Citation2018).

Research on the activity and behavior of anglers in Indonesia has not been widely carried out even if fishing is one of the sports activities that are closely related and interrelated with the existing socio-culture in Indonesian society. Therefore, we conducted a survey using an online questionnaire to assess the possible use of live crayfish as bait in this Southeast Asian island country.

Material and Method

Study Area

Indonesia is the largest archipelago of the world, lies between latitudes 11°S and 6°N, and longitudes 95°E and 141°E. Indonesia is grouped into the Greater Sunda Islands of Sumatra (Sumatera), Java (Jawa), the southern extent of Borneo (Kalimantan), and Celebes (Sulawesi); the Lesser Sunda Islands (Nusa Tenggara) of Bali and a chain of islands that runs eastward through Timor; the Moluccas (Maluku) between Celebes and the island of New Guinea; and the western extent of New Guinea (generally known as Papua). The questionnaire was distributed to the whole territory of Indonesia to get responses that could represent the angling behavior of Indonesian anglers. Respondents were grouped based on their respective home islands.

Data Collection

Survey recruitment and distribution were conducted from March to September 2020. Data collection was carried out using an anonymous questionnaire given to anglers as respondents in the Indonesian language (Bahasa Indonesia). The target population included recreational anglers aged 20 years and older who actively fish in freshwaters. The online questionnaire was distributed through social media (WhatsApp Group, Line, and Facebook messenger) and local fishing groups on Facebook. The survey was conducted using the Google Form platform (https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSep7SAAetok6JzFcrwRU2_7GB0nOhXBVgRLs6_rqQrIVvLwuQ/viewform?usp=pp_url). The questionnaire included a series of closed and open-ended questions that investigated various socio-psychological parameters and types of bait used by Indonesian anglers. Summary statistics and graphs were generated using MS Excel. The main part of the questionnaire included questions addressed: (1) fishing locations; (2) the type of bait used (including live animals); (3) bait prices; (4) the number of baits; (5) the common or formal name of the live bait used; (6) where did the live bait come from; (7) the effectivity of using crayfish as bait; (8) disposal or releasing the crayfish used as bait. Potential answers related to bait were categorized based on the modified main types from Keller et al. (Citation2007): namely Fish, Crayfish, and Shrimps. In this paper, we present the percentage of response data for questions that address bait use, source, and disposal.

Anglers using bait that did not fit into one of these categories were asked to specify the “other” bait types used and were assigned the “other” category to answer questions regarding the source, location of use, and disposal. Even if the questionnaire was anonymous, respondents were contacted via e-mail to confirm their answers if necessary. This can be done because when respondents filled out the questionnaire their e-mail addresses were recorded automatically even if not stored for future analysis.

Data Analysis

Collected data were classified based on the value obtained by multiplying the predetermined category weight by the number of respondents who fall into the same category. From the data obtained, the average value and standard deviation were sought to determine the amount of concentration and the magnitude of the diversity of respondents’ answers. The analytical plan was previously defined and recognized, and any data-driven analyses were adequately discussed.

Data analyses were performed using the statistical package IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac OS, Version 29.0.0.0–241 (Copyright IBM Corporation 1989, 2022). Descriptive statistics were conducted. Data were expressed as frequency (n) and percentage (%) for categorical data and median (min-max) for continuous data. Multinominal logistic regression analyses were applied for the assessment of the interactions of these factors. Significance values (p-values) were given in all estimated multinominal logistic regression models. Statistical significance for all tests was set at a p-value of 0.05.

Results

Home Island, Main Job, and Age of Respondents

The number of respondents in this study amounted to 148 anglers from the nine home islands, namely: Bali, Bintan, Java, Kalimantan (Indonesian part of Borneo), Lombok, Maluku, Papua (Indonesian part of New Guinea), Sulawesi, and Sumatra. The highest percentage of respondents was obtained from Sumatra (34%), followed by Java (20%), and Kalimantan (12%; ). These values can be explained by the extension of islands and their population.

The main day job of anglers varies: there were 50 employees, 36 entrepreneurs, 21 government employees, 15 farmers, 13 college students, 8 retirees, and 3 teachers. The minimum age of respondents in this study was 20 years and a maximum of 60 years. The distribution of the age groups and main occupations is presented in .

Figure 2. Age distribution based on the type of work of anglers in Indonesia. Error bars show the confidence interval or standard error of the mean, that shows how much error is built into the chart.

In this study, the multinominal logistic regression analysis has been used in the analysis. Pearson test results showed p > 0.05, which means the model is appropriate to use (). The likelihood Ratio Test is to decrease after several iterations if there is a relation to a certain extent between dependent and independent factors. Chi-Square test statistic has resulted significantly (p < 0.05), where the factors affecting the preference of bait are the main job and home island (). Generally interpreting the table, the independent variable is subject to the dependent factor to a certain extent. Calculated Pseudo R2 values are quite high and the relationship between dependent and independent variables is quite strong and significant ().

Table 1. Goodness of fit results.

Table 2. Likelihood Ratio Test results.

Table 3. Pseudo R-Square results.

Source, Types, and Price of Bait

The source of the bait reportedly comes from cricket breeders, farmland, lakes/reservoirs, rivers, and fishing stores. Common names for bait used by anglers in Indonesia included earthworms, crickets, crayfish, and fresh meals (). Generally, the use of live crayfish as bait in Indonesia was confirmed.

Table 4. The types of status in Indonesia, location of use, and sources of bait reported by anglers in Indonesia. The Sum of percentages exceeds 100% for bait types for which multiple sources were reported by some respondents.

The price of bait used by anglers in Indonesia varies from free to IDR 18,600 (USD 1.20). Most people get their bait from farmland or prepare the bait themselves. Fresh food is usually sold in packs for an average price of IDR 7,750 (USD 0.5). Crayfish and crickets are sold at prices starting from IDR 1,550 (USD 0.1) to IDR 7,750 (USD 0.5) per individual.

Habitats Where Anglers Use Bait

Bait is used by anglers in all freshwater habitats over the entire Indonesian territory. The majority of anglers use bait in lakes/reservoirs, rivers, and ponds (). It is reported that cricket bait is frequently used in rivers (9%) and reservoirs (1%), while earthworms are used in lakes/reservoirs (4%), ponds (1%), and rivers (4%), fresh meal is used in ponds (54%), and crayfish are usually used in lakes/reservoirs (1%), ponds (2%), and rivers (10%; ).

Live Crayfish Use as Bait

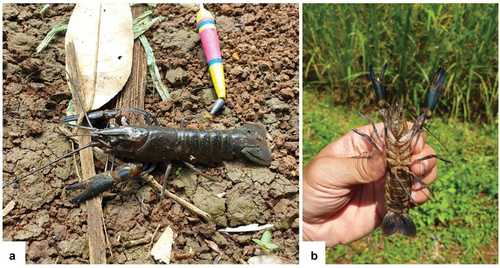

Anglers use crayfish as an alternative bait in fishing in Indonesia (13%). Although most anglers were unable to correctly identify the crayfish species, there is only one species of crayfish, redclaw (Cherax quadricarinatus), recorded as being used as live bait in Indonesia (). The majority of anglers using this method reported that the catch is greater with the use of live crayfish (32%) and it is easier to fish (18%). In this study, it was reported that anglers using crayfish retain unused bait until the next fishing trip or give unused bait to other anglers, and at least 50% of anglers release it alive into the water on the locality. Other methods of disposal included feeding their pets or domestic animals with unused bait. It is undeniable, that some crayfish accidentally escaped or are unintentionally released into the water when the anglers apply a new bait.

Discussion

The results of the questionnaire survey confirm that the use of crayfish Cherax quadricarinatus as live bait is a common practice of Indonesian anglers. It is worth mentioning that the majority of anglers were unable to correctly identify the crayfish species. Generally, it is known that many anglers do not know and do not care about the scientific name or origin of the bait used (DiStefano et al., Citation2009). Our survey showed that non-native bait species potentially invasive in Indonesian waters are likely to be both intentionally and accidentally released by anglers in the wild.

The release of unused live bait is frequent behavior of anglers even if this varies according to the type of bait (Jenkins, Citation2003; Nathan et al., Citation2015). Anglers usually release bait that is no longer used or accidentally while fishing. Live bait either purchased or collected from the wild is often released into non-native river basins (Litvak & Mandrak, Citation1993). Since many non-native species are used as live bait, their release is a pathway of potential biological invasion (Charlebois & Lamberti, Citation1996; Olsen et al., Citation1991; Strayer, Citation2010). In the case of C. quadricarinatus, this species is invasive in the vast majority of Indonesian territory except for a southern part of the Papua Province in New Guinea (Bláha et al., Citation2016; Patoka et al., Citation2016, Citation2018b; Akmal et al., Citation2021). The crayfish used as bait mostly originated from field capture because C. quadricarinatus is widely distributed in Indonesia (Patoka et al., Citation2018a; Akmal et al., Citation2021). It should be noted that there are more potentially attractive crayfish species that can be used as live bait in Indonesia in future. Especially red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii), the North American species which was found in culture in Java (Putra et al., Citation2018) can be exploited for this purpose. This possibility is of concern for conservationists and alarming due to the confirmed invasion potential of the species in Indonesia and also by crayfish plague disease which is transmitted via this crayfish host. The price of C. quadricarinatus in the Indonesian fish market is IDR 7,750 (USD 0.5) per individual, while IDR 16,300 (USD 1.05) in P. clarkii (Yuliana et al., Citation2021). Cherax quadricarinatus is cheaper and thus has a higher potential to be used as live bait. Since the anglers have a poor ability to correctly identify the species, nobody cares about the risks related to the potential invasion.

Cherax quadricarinatus has a high level of tolerance to environmental conditions as well as a high rate of growth and fertility (Akmal et al., Citation2021; Haubrock et al., Citation2021; Patoka et al., Citation2016). In addition to affecting major ecosystem functioning, invasive species that are used as live bait are generally associated with the decline or elimination of native species through hybridization, competition, predation, pathogen transmission, and habitat degradation and alteration (Herder et al., Citation2014; Keller et al., Citation2007; Litvak & Mandrak, Citation1993; Strand et al., Citation2014). The use of live bait was identified as the pathway responsible for the introduction of the crayfish into waters out of their native range such as in Maryland, USA, where anglers using crayfishes released their unused bait (Kilian et al., Citation2012).

Generally, many anglers believe that the release of unwanted live bait is beneficial to the receiving ecosystem (Litvak & Mandrak, Citation1993). Based on comments provided by anglers on our survey forms, some Indonesian anglers also believe that their actions are humane, legal and that the release of unused bait benefits gamefish populations. Most of the anglers in Indonesia are not aware that this is risky for the environment and can cause environmental damage. Understanding the source, sale and use of live bait is critical to developing and implementing appropriate policies on invasive species (Keller & Lodge, Citation2007), effectively focusing on regulation, and targeting public education efforts to reduce bait-related introductions.

The risks posed by the import of non-native bait species in general and crayfish, in particular, can be reduced if Indonesian anglers are aware of the prohibition of releasing animals into Indonesian waters without permission. This should be of concern to the government to protect native Indonesian species by regulating them in statutory regulations. Even if the Indonesian legislative regulations are ineffective in many cases (Patoka et al., Citation2018b), the policymakers considered improving the situation by promoting the new law No. 27/2021 focused on the prevention of invasive species introduction and spread. Thus, non-native species imported into Indonesia, or which are accidentally or deliberately released into the waters can be controlled, when identified as invaders causing environmental losses (Yonvitner et al., Citation2020).

The regulations focused on nature conservation usually fails in the regulation of the release of live bait as a broader vector of invasive species (Peters & Lodge, Citation2009). The application of regulations, monitoring, and enforcement of animal releases in waters vary greatly among provinces in Indonesia. This decree is contained in certain regional regulations. One of the regions that have implemented this regulation is Yogyakarta. To anticipate the increasingly dynamic spread of invasive and risky aquatic species, the government then issued several laws and regulations namely Decree of the Head of the Fish Quarantine Inspection Agency No. 107/KEP-BKIPM/2017 about Guidelines for Invasive Alien Species Risk Analysis. Effective prevention of the release of invasive bait species in this case of crayfish requires greater control effort and intensive monitoring (Kilian et al., Citation2012).

These actions will also enhance the ability of state management agencies to target regulations regarding invasive bait species appropriately and effectively, disseminate educational materials and public outreach to users/anglers, and enforce current and future regulations involving identified invasive taxa (Drake & Mandrak, Citation2014). Anglers in the present study reported that self-collection is an important source of all types of bait, especially crayfish. Efforts aimed at changing this anglers’ behavior using a combination of regulation and education are needed to prevent the further spread of invasive species in Indonesia.

There is a need to develop strategies that can effectively increase the understanding of Indonesian anglers and change their attitudes and behavior regarding bait use and disposal by engaging anglers’ communities in Indonesia. The use of native shrimp as live bait is proposed to be preferably used to minimize the release of non-native bait crayfish species into the waters. The next suggestion is to formulate a policy at the regional level regarding the regulation of the use of live bait organisms identified as risky such as non-native crayfish. This regulation needs to be issued immediately to avoid the spread of C. quadricarinatus which is used as live bait and invades Indonesian waters massively.

Author Contributions

JP, SGA; methodology, software: JP, SGA; validation: JP, Y, FY, LA; formal analysis, investigation, field work, resources, data curation: SGA; writing – original draft preparation: SGA; writing – review and editing: JP, Y, FY, LA.; visualization, author of pictures: SGA; supervision: JP, Y, FY, LA. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ernan Rustiadi for his support. SGA and JP were supported by the European Regional Development Fund: Submitted article was supported within the frame of the comprehensive project named “Centre for the investigation of synthesis and transformation of nutritional substances in the food chain in interaction with potentially harmful substances of anthropogenic origin: comprehensive assessment of soil contamination risks for quality of agricultural products” (No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/16_091/0000845). JP was supported by the Technology Agency of the Czech Republic within the project, “DivLand” (SS02030018). This study was supported by the Indonesian Center for Research on Bioinvasions. English was proofread by Julian D. Reynolds.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [SGA]upon reasonable request.

References

- Akmal, S. G., Santoso, A., Yonvitner, Yuliana, E., & Patoka, J. (2021). Redclaw crayfish (Cherax quadricarinatus): Spatial distribution and dispersal pattern in Java, Indonesia. Knowledge and Management of Aquatic Ecosystems, 422, 16. https://doi.org/10.1051/kmae/2021015

- Anderson, R. O. (1982). Managing ponds for good fishing. University of Missouri-Columbia Extension Division.

- Arlinghaus, R., Tillner, R., & Bork, M. (2015). Explaining participation rates in recreational fishing across industrialised countries. Fisheries Management and Ecology, 22(1), 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/fme.12075

- Bakker, C. V., Kardaun, S. H., Wilting, K. R., Diercks, G. F. H., & Horváth, B. (2013). Why you should ask your patients about their fishing hobbies. The Journal of Medicine, 71(7), 366–368.

- Ball, R. L., & Tousignant, J. N. (1996). The Development of an objective rating system to assess bluegill fishing in lakes and ponds. Indiana Department of Natural Resources.

- Bērziņš, V. (2010). Fishing seasonality and techniques in prehistory: Why freshwater fish are special. Archaeologia Baltica, 13, 37–42.

- Bláha, M., Patoka, J., Kozák, P., & Kouba, A. (2016). Unrecognized diversity in New Guinean crayfish species (Decapoda, Parastacidae): The evidence from molecular data. Integrative Zoology, 11(6), 457–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/1749-4877.12211

- Carpenter, S. R., & Brock, W. A. (2004). Spatial complexity, resilience, and policy diversity: Fishing on lake-rich landscapes. Ecology and Society, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-00622-090108

- Charlebois, P. M., & Lamberti, G. A. (1996). Invading crayfish in a Michigan stream: Direct and indirect effects on periphyton and macroinvertebrates. Journal of the North American Benthological Society, 15(4), 551–563. https://doi.org/10.2307/1467806

- Cooke, S. J., & Cowx, I. G. (2004). The role of recreational fishing in global fish crises. BioScience, 54(9), 857–859. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-35682004054[0857:TRORFI]2.0.CO;2

- Cowx, I. G. (2002). Handbook of fish biology and fisheries. Volume 2: Fisheries. In Recreational fishing pp. 367–390.https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470693919.ch17

- Darmanin, A. S., & Vella, A. (2018). An assessment of catches of shore sport fishing competitions along the coast of the Maltese Islands: Implications for conservation and management. Fisheries Management and Ecology, 25(2), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/fme.12271

- de Bruyn, M., Stelbrink, B., Morley, R. J., Hall, R., Carvalho, G. R., Cannon, C. H., van den Bergh, G., Meijaard, E., Metcalfe, I., Boitani, L., Maiorano, L., Shoup, R., & von Rintelen, T. (2014). Borneo and Indochina are major evolutionary hotspots for Southeast Asian biodiversity. Systematic Biology, 63(6), 879–901. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syu047

- DiStefano, R. J., Litvan, M. E., & Horner, P. T. (2009). The bait industry as a potential vector for alien crayfish introductions: Problem recognition by fisheries agencies and a Missouri evaluation. Fisheries, 34(12), 586–597. https://doi.org/10.1577/1548-8446-34.12.586

- Drake, D. A. R., & Mandrak, N. E. (2014). Ecological risk of live bait Fisheries: A new angle on selective fishing. Fisheries, 39(5), 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/03632415.2014.903835

- Fagan, B. (2017). Fishing: How the sea fed civilization. Yale University Press.

- Fišáková, J., Patoka, M. N., Kalous, L., Škrdla, P., Kuča, M., Kalous, L., Patoka, J., Nývltová Fišáková, M., Kalous, L., Škrdla, P., Patoka, J., Nývltová Fišáková, M., Kalous, L., Škrdla, P., & Kuča, M. (2014). Earliest evidence for human consumption of crayfish. Crustaceana, 87(13), 1578–1585. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685403-00003368

- Fitriani, M., Wudstisin, I., & Kaewnern, M. (2019). Potency and barrier of the small-scale aquaculture development in reclaimed tidal lowlands, South Sumatera, Indonesia. International Journal of Environmental and Rural Development, 10(1), 167–172. https://doi.org/10.32115/ijerd.10.1_167

- Goodchild, C. D. (2000). Ecological impacts of introductions associated with the use of live bait. In R. Claudi & J. Leach (Eds.), Nonindigenous freshwater organisms: Vectors, biology, and impacts (pp. 181–202). Lewis Publisher.

- Hancz, C. (2020). Feed efficiency, nutrient sensing and feeding stimulation in aquaculture: A review. Acta Agraria Kaposváriensis, 24(1), 35–54. https://doi.org/10.31914/aak.2375

- Haubrock, P. J., Oficialdegui, F. J., Zeng, Y., Patoka, J., Yeo, D. C. J., & Kouba, A. (2021). The redclaw crayfish: A prominent aquaculture species with invasive potential in tropical and subtropical biodiversity hotspots. Reviews in Aquaculture, 13(3), 1488–1530. https://doi.org/10.1111/raq.12531

- Herder, J., Valentini, A., Bellemain, E., Dejean, T., van Delfit, J., Thomsen, P. F., & Taberlet, P. (2014). Environmental DNA: A review of the possible applications for the detection of (invasive) species. Stichting RAVON.

- Hummel, R. L. (1994). Hunting and fishing for sport: Commerce, controversy, popular culture. Bowling Green State University Popular Press.

- Jenkins, T. M. (2003). Evaluating recent innovations in bait fishing tackle and technique for catch and release of rainbow trout. North American Journal of Fisheries Management, 23(4), 1098–1107. https://doi.org/10.1577/M02-040

- Keller, R. P., Cox, A. N., van Loon, C., Lodge, D. M., Herborg, L.-M., & Rothlisberger, J. (2007). From bait shops to the forest floor: Earthworm use and disposal by anglers. The American Midland Naturalist, 158(2), 321–328. https://doi.org/10.1674/0003-00312007158[321:FBSTTF]2.0.CO;2

- Keller, R. P., & Lodge, D. M. (2007). Species invasions from commerce in live aquatic organisms: Problems and possible solutions. BioScience, 57(5), 428–436. https://doi.org/10.1641/B570509

- Kilian, J. V., Klauda, R. J., Widman, S., Kashiwagi, M., Bourquin, R., Weglein, S., & Schuster, J. (2012). An assessment of a bait industry and angler behavior as a vector of invasive species. Biological Invasions, 14(7), 1469–1481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-012-0173-5

- Litvak, M. K., & Mandrak, N. E. (1993). Ecology of freshwater baitfish use in Canada and the United States. Fisheries, 18(12), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1577/1548-84461993018<0006:EOFBUI>2.0.CO;2

- Lohman, D. J., de Bruyn, M., Page, T., von Rintelen, K., Hall, R., Ng, P. K. L., Shih, H.-T., Carvalho, G. R., & von Rintelen, T. (2011). Biogeography of the Indo-Australian Archipelago. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 42(1), 205–226. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102710-145001

- Lukhaup, C. (2015). Cherax (Astaconephrops) pulcher, a new species of freshwater crayfish (Crustacea, Decapoda, Parastacidae) from the Kepala Burung (Vogelkop) Peninsula, Irian Jaya (West Papua), Indonesia. ZooKeys, 502, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.502.9800

- Lukhaup, C., & Pekny, R. (2006). Cherax (Cherax) holthuisi, a new species of crayfish (Crustacea: Decapoda: Parastacidae) from the centre of the Vogelkop Peninsula in Irian Jaya (West New Guinea), Indonesia. Zoologische Mededelingen, 80(7), 101–107.

- Marková, J., Jerikho, R., Wardiatno, Y., Kamal, M. M., Magalhães, A. L. B., Bohatá, L., Kalous, L., & Patoka, J. (2020). Conservation paradox of giant arapaima Arapaima gigas (Schinz, 1822) (Pisces: Arapaimidae): Endangered in its native range in Brazil and invasive in Indonesia. Knowledge and Management of Aquatic Ecosystems, 421, 47. https://doi.org/10.1051/kmae/2020039

- McIntosh, P. (2011). Fishing a Sport for All Seasons. English Teaching Forum, 49(2), 36–43 .

- Muawanah, U., Yusuf, G., Adrianto, L., Kalther, J., Pomeroy, R., Abdullah, H., & Ruchimat, T. (2018). Review of national laws and regulation in Indonesia in relation to an ecosystem approach to fisheries management. Marine Policy, 91, 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.01.027

- Nadler, J. T., Bartels, L. K., Sliter, K. A., Stockdale, M. S., & Lowery, M. (2013). Research on the discrimination of marginalized employees: Fishing in other ponds. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 6(1), 66–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/iops.12009

- Nathan, L. R., Jerde, C. L., Budny, M. L., & Mahon, A. R. (2015). The use of environmental DNA in invasive species surveillance of the Great Lakes commercial bait trade. Conservation Biology, 29(2), 430–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12381

- Oh, C.-O., Sutton, S. G., & Sorice, M. G. (2013). Assessing the role of recreation specialization in fishing site substitution. Leisure Sciences, 35(3), 256–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2013.780534

- Olden, J. D., McCarthy, J. M., Maxted, J. T., Fetzer, W. W., & Vander Zanden, M. J. (2006). The rapid spread of rusty crayfish (Orconectes rusticus) with observations on native crayfish declines in Wisconsin (U.S.A.) over the past 130 years. Biological Invasions, 8(8), 1621–1628. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-005-7854-2

- Olsen, T. M., Lodge, D. M., Capelli, G. M., & Houlihan, R. J. (1991). Mechanisms of impact of an introduced crayfish (Orconectes rusticus) on Littoral Congeners, Snails, and Macrophytes. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 48(10), 1853–1861. https://doi.org/10.1139/f91-219

- Patoka, J., Bláha, M., & Kouba, A. (2015). Cherax (Astaconephrops) gherardii, a new crayfish (Decapoda: Parastacidae) from West Papua, Indonesia. Zootaxa, 3964(5), 526–536. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3964.5.2

- Patoka, J., Bláha, M., & Kouba, A. (2017). Cherax acherontis (Decapoda: Parastacidae), the first cave crayfish from the Southern Hemisphere (Papua Province, Indonesia). Zootaxa, 4363(1), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4363.1.7

- Patoka, J., Magalhães, A. L. B., Kouba, A., Faulkes, Z., Jerikho, R., & Vitule, J. R. S. (2018a). Invasive aquatic pets: Failed policies increase risks of harmful invasions. Biodiversity and Conservation, 27(11), 3037–3046. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-018-1581-3

- Patoka, J., Takdir, M., Yonvitner, Aryadi, H., Jerikho, R., Nilawati, J., Tantu, F. Y., Bohatá, L., Aulia, A., Kamal, M. M., Wardiatno, Y., & Petrtýl, M. (2020). Two species of illegal South American sailfin catfish of the genus Pterygoplichthys well-established in Indonesia. Knowledge and Management of Aquatic Ecosystems, 421, 28. https://doi.org/10.1051/kmae/2020021

- Patoka, J., Wardiatno, Y., Mashar, A., Yonvitner, Wowor, D., Jerikho, R., Takdir, M., Purnamasari, L., Petrtýl, M., Miloslav, P., Kouba, A., & Bláha, M. (2018b). Redclaw crayfish, Cherax quadricarinatus (von Martens, 1868), widespread throughout Indonesia. BioInvasions Records, 7(2), 185–189. https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2018.7.2.11

- Patoka, J., Wardiatno, Y., Yonvitner, Kuříková, P., Petrtýl, M., & Kalous, L. (2016). Cherax quadricarinatus (von Martens) has invaded Indonesian territory west of the Wallace Line: Evidences from Java. Knowledge and Management of Aquatic Ecosystems, 417, 39. https://doi.org/10.1051/kmae/2016026

- Persoon, G. A., & van Weerd, M. (2006). Biodiversity and natural resource management in insular Southeast Asia. Island Studies Journal, 1(1), 81–108. https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.189

- Peters, J. A., & Lodge, D. M. (2009). Invasive species policy at the regional level: A multiple weak links problem. Fisheries, 34(8), 373–380. https://doi.org/10.1577/1548-8446-34.8.373

- Pitcher, T. J., & Hollingworth, C. E. (Eds.). (2002). Recreational Fisheries: Ecological, Economic and Social Evaluation. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470995402

- Purwanto, S. A. (2018). Back to the river. Changing livelihood strategies in Kapuas Hulu, West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods, 27(3), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/14728028.2018.1446849

- Putra, M. D., Bláha, M., Wardiatno, Y., Krisanti, M., Yonvitner, Jerikho, R., Kamal, M., Mojžišová, M., Bystřický, P. K., Kouba, A., Kalous, L., Petrusek, A., Patoka, J. (2018). Procambarus clarkii (Girard, 1852) and crayfish plague as new threats for biodiversity in Indonesia. Aquatic Conservation, 28(6), 1434–1440. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2970

- Rochet, M. (1998). Short-term effects of fishing on life history traits of fishes. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 55(3), 371–391. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmsc.1997.0324

- Rostitawati, T., Wahyuddin, N. I., & Obie, M. (2019). The poverty puddles of the cage fishing community at Limboto lake coast, Indonesia. Journal of Sustainable Development, 12(3), 82. https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v12n3p82

- Sahrhage, D., & Lundbeck, J. (1992). A History of Fishing. Springer-Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-77411-9

- Salas, S., & Gaertner, D. (2004). The behavioural dynamics of fishers: Management implications. Fish and Fisheries, 5(2), 153–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2979.2004.00146.x

- Skrzypczak, A. R., & Karpiński, E. A. (2020). New insight into the motivations of anglers and fish release practices in view of the invasiveness of angling. Journal of Environmental Management, 271, 111055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111055

- Strand, D. A., Jussila, J., Johnsen, S. I., Viljamaa-Dirks, S., Edsman, L., Wiik-Nielsen, J., Viljugrein, H., Engdahl, F., Vrålstad, T., & Morgan, E. (2014). Detection of crayfish plague spores in large freshwater systems. Journal of Applied Ecology, 51(2), 544–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12218

- Strayer, D. L. (2010). Alien species in fresh waters: Ecological effects, interactions with other stressors, and prospects for the future. Freshwater Biology, 55, 152–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2009.02380.x

- Vaughan, W. J., & Russell, C. S. (1982). Freshwater recreational fishing: The national benefits of water pollution control. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Yonvitner, Patoka, J., Yuliana, E., Bohatá, L., Tricarico, E., Karella, T., Kouba, A., Reynolds, J. D., & Yonvitner, Y. (2020). Enigmatic hotspot of crayfish diversity at risk: Invasive potential of non‐indigenous crayfish if introduced to New Guinea. Aquatic Conservation, 30(2), 219–224. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.3276

- Yuliana, E., Yonvitner, Akmal, S. G., Subing, R. A., Ritonga, S. A. R., Santoso, A., Kouba, A., Patoka, J. (2021). Import, trade and culture of non-native ornamental crayfish in Java, Indonesia. Management of Biological Invasions, 12(4), 846–857. https://doi.org/10.3391/mbi.2021.12.4.05

- Zeng, Y., Chong, K. Y., Grey, E. K., Lodge, D. M., & Yeo, D. C. J. (2015). Disregarding human pre-introduction selection can confound invasive crayfish risk assessments. Biological Invasions, 17(8), 2373–2385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-015-0881-8