ABSTRACT

Human tolerance for wildlife is a key consideration for managers and has been measured with attitudes, normative beliefs, and behaviors. The study objectives were to determine, in the context of Alabama hunters’ tolerance for non-native, invasive wild pigs, 1) the convergent validity among three cognitive measures of tolerance, and 2) the strength of association between the cognitive measures of tolerance and behavioral measures of tolerance. Results revealed that general attitudes and wildlife acceptance capacity had high convergent validity suggesting that both quantify similar and highly related psychological aspects of tolerance. Conversely, the standard cognitive measures had low predictive associations with most behavioral measures suggesting a lack of interchangeability of behavioral and cognitive measures for purposes of operationalizing tolerance. We highlight how our findings are affected by the complexity of hunter-wild pig interactions and emphasize the importance of assessing tolerance in different contexts to provide greater conceptual clarity.

Introduction

The concept of human tolerance for wildlife, which broadly refers to an individual’s willingness to live alongside a particular species, is recognized as an essential consideration in modern wildlife management (Gigliotti et al., Citation2000). This latent, psychological concept is often used to quantify human preferences for wildlife populations (Lischka et al., Citation2019), and understanding and potentially influencing those preferences may be a central goal for agencies that seek to mitigate negative human-wildlife interactions (Pooley et al., Citation2017). Underscoring the significance of the concept, a group of distinguished wildlife conservation scholars and professionals concluded that understanding the factors that shape human tolerance of wildlife is among the 100 scientific questions of greatest importance to global biodiversity conservation (Sutherland et al., Citation2009). Most commonly, tolerance has been studied in conservation contexts to understand human preferences for large predators such as canines, felines, and ursids (e.g., Cleary et al., Citation2021; Inskip et al., Citation2016), as well as other native species like white-tailed deer that sometimes come into conflict with humans (Lischka et al., Citation2008). Understanding tolerance is considered a key component of human-wildlife coexistence in these contexts, with conservation initiatives endeavoring to increase human tolerance to protect wildlife (Frank, Citation2016).

Relatively fewer tolerance studies have focused on species that were not of conservation concern, including non-native, invasive species. In this realm, studies have included investigations of tolerance for free-roaming domestic cats (Felis catus; Wald & Jacobson, Citation2013) and more recently, invasive wild pigs (Sus scrofa) in the United States (McLean et al., Citation2021). In the invasive species context, tolerance may be no less important from a management perspective, but it often has different implications. Unlike in conservation contexts, high levels of tolerance for an invasive species (e.g., among hunters who wish to maintain a population of the species to hunt) may frustrate management initiatives insofar as the goal is population reduction or elimination. In such situations, understanding tolerance levels can inform the development of outreach and engagement efforts that aim to influence perceptions of the species and foster an understanding of the need to control or eliminate their populations (McLean et al., Citation2021).

Despite the tolerance concept’s frequent and widespread utility and application in wildlife management research, scholars have been inconsistent in their conceptualization of it, as evidenced by the various definitions and measures employed by scholars (Brenner & Metcalf, Citation2020; Delie et al., Citation2022). For example, tolerance has been defined as “accepting wildlife and/or wildlife behaviors that one dislikes” (Brenner & Metcalf, Citation2020, p. 262), “passive acceptance of a wildlife population” (Bruskotter & Fulton, Citation2012), and “the willingness of an individual to absorb the extra potential or actual costs of living with wildlife” (Kansky et al., Citation2016, p. 138). Some researchers have also begun to move toward a more affirmative framing of tolerance that encompasses positive attitudes and benefit-related beliefs, such as one’s belief that there is value in the existence of wildlife on the landscape (Frank & Glikman, Citation2019). Within this framing, tolerance for wildlife has been defined as, “an individual’s or group’s acceptance of negative effects and desire for positive effects arising from interactions with wildlife populations” (Lischka et al., Citation2019, p. 1).

In operationalizing the tolerance concept, researchers have commonly used cognitive measures, such as psychometric items and scales reflective of general attitudes (e.g., Kansky & Knight, Citation2014; Lewis et al., Citation2012; Zimmermann et al., Citation2005). Attitudes, a foundational concept in social psychology, have been defined as a tendency to respond favorably or unfavorably toward an issue, object, person, etc (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2010). As an attitude, tolerance has been measured by respondents’ propensity to report negative, neutral, or positive opinions toward a species (Kansky & Knight, Citation2014; Lewis et al., Citation2012). Respondents who hold more negative attitudes toward a wildlife species are generally considered to have lower tolerance for the species, and vice versa (Lewis et al., Citation2012). For example, Zimmermann et al. (Citation2005) operationalized tolerance by asking respondents to reflect on six attitudinal statements about jaguars on a 5-point scale (0 = “strongly negative” to 4 = “strongly positive”) and then summating their responses, with higher scores indicating a more positive attitude toward or greater tolerance for jaguars.

A highly related concept known as wildlife acceptance capacity (WAC) was introduced by Decker and Purdy (Citation1988) to refer to the maximum wildlife population size in an area that humans find acceptable. As Bruskotter and Fulton (Citation2012) note, the introduction of the WAC concept resulted in two parallel lines of research (tolerance and WAC) that effectively investigated the same construct. In recent years, however, WAC has frequently been subsumed into the tolerance concept, with researchers commonly using it as the standard approach to quantifying tolerance and operationalizing it by asking study participants whether they believe a wildlife population should increase, decrease, or remain the same size (e.g., Inskip et al., Citation2016; Lischka et al., Citation2019; McLean et al., Citation2021; Struebig et al., Citation2018). In these studies, a preference for a decreased population of a species was interpreted to correspond to lower tolerance for the species, and vice versa.

Further contributing to the lack of conceptual clarity, the acceptability of various wildlife management actions for a species has also been used as a measure of tolerance (e.g., Morzillo & Needham, Citation2015). For example, Hosaka et al. (Citation2017) assessed tolerance by measuring the acceptability of wildlife management actions (from “do nothing” to “trap and eliminate the animal”) of hornets and wild boar in different conflict scenarios on a 5-point scale (1 = “totally unacceptable” to 5 = “totally acceptable”). Human tolerance thresholds for a species have been inferred from these types of measurements (Brenner & Metcalf, Citation2020). Individuals who find lethal management interventions for a species to be generally acceptable in most scenarios, for example, are typically inferred to be less tolerant of the species under study.

Beyond the cognitive or attitudinal dimensions of tolerance, many researchers have posited that behaviors are also integral to the concept (e.g., Bruskotter & Wilson, Citation2014; Kansky et al., Citation2021). Bruskotter et al. (Citation2015), for example, note that measuring tolerance for wildlife is inevitably an attempt to understand at what point humans will take action to reduce a species’ population because it has exceeded an acceptable threshold size. The view that tolerance encompasses cognitive and behavioral elements is consistent with the IUCN SSC Guidelines on Human-Wildlife Conflict and Coexistence (IUCN, Citation2023), which state, “Tolerance can take both attitudinal forms (e.g., attitudes toward a species, judgments concerning the acceptability of a species) and behavioral forms (e.g., overt illegal killing, political protests)” (p. 57). In a survey of visitors to a popular wildlife blog, Bruskotter et al. (Citation2015) demonstrated that not only were behaviors a relevant dimension of the tolerance concept, but that measures for relevant behaviors and behavioral intentions were highly correlated with general attitudes (in this study, toward wolves) and WAC. Effectively, they found that the cognitive measures of tolerance were good predictors of tolerant and intolerant behaviors and behavioral intentions (Bruskotter et al., Citation2015). Moreover, they suggested that because of the high strength of association between the cognitive and behavioral measures, either could be used to measure tolerance (see also Treves, Citation2012).

While the findings of Bruskotter et al. (Citation2015) provided important insights concerning the relationship between cognitive and behavioral measures of tolerance in their study context, more research is needed to understand whether this observed attitude-behavior consistency is reflected in other contexts (Brenner & Metcalf, Citation2020; Delie et al., Citation2022), including those involving different species and study populations. Indeed, attitude-behavior consistency theory recognizes that attitudes are often not good predictors of behaviors, and that attitude-behavior consistency varies depending on how the concepts are measured, the topic being studied, and the strength of the associated attitudes (Gross & Niman, Citation1975). Moreover, it is uncertain whether the various cognitive measures of tolerance that have been used to operationalize the concept in a conservation context are sufficiently correlated in other wildlife management contexts to constitute valid measures of the same concept. To address this gap, we examined both cognitive and behavioral measures of tolerance in the context of hunters’ tolerance for invasive wild pigs in Alabama. The objectives of this study were to determine 1) the convergent validity among the three cognitive measures of tolerance (general attitudes, WAC, and acceptability of management actions), and 2) the strength of association between the cognitive measures of tolerance and the behavioral measures of tolerance (prior behaviors and behavioral intentions). With the first objective, we intended to understand whether the three cognitive measures were sufficiently correlated such that they could be said to measure the same construct (i.e., tolerance) in our study context. With the second objective, we sought to understand whether the cognitive measures were good predictors of relevant behaviors and behavioral intentions in our study context. In doing so, we were responding to and building on the findings of Bruskotter et al. (Citation2015). Secondarily, we endeavored to provide practical information about hunters’ tolerance for wild pigs in Alabama that could inform wild pig control initiatives in the state.

Methods

Study Context

Located in the Southeastern region of the United States, Alabama is a geographically diverse state with notable portions of land area comprised of farm operations (27%) and timberlands (69%) (Fern et al., Citation2021). Wild pigs can be found in 64 of the state’s 67 counties where they cause extensive damage to agriculture and natural resources (Fern et al., Citation2021). In a study that assessed wild pig damage to six crop types, McKee et al. (Citation2020) found that 31% of Alabama producers experienced crop damage, and 34% experienced property damage in 2018 (McKee et al., Citation2020). Another study found that approximately 20% of Alabama timber producers experienced wild pig damage to their young forest stands between 2013–2015 (Fern et al., Citation2021). In total, damages from wild pigs cost Alabama agricultural producers tens of millions of dollars annually (Fern et al., Citation2021; McKee et al., Citation2020).

Despite their negative impacts, research has shown that some U.S. hunters find value in wild pigs and may promote interest in maintaining populations for hunting (Caudell et al., Citation2016; McLean et al., Citation2021). In addition, evidence suggests that some hunters have translocated wild pigs to uninvaded areas for hunting purposes (Grady et al., Citation2019), an activity that has contributed to the spread of the species. While Alabama now prohibits the possession, transport, and/or release of wild pigs (Al. Admin. Code § 220-2-.86), it has few limitations on hunting wild pigs even though the activity may create demand for the species on the landscape. Wild pigs are classified as game animals (Al. Admin. Code § 220-2-.06) that can be pursued, without a bag limit, during any season on private land in Alabama (Al. Admin. Code §§ 220-2-.01). Moreover, Alabama began issuing licenses in 2021 to allow the hunting of wild pigs at night (Rainer, Citation2022). Such measures could increase tolerance for the species among hunters, potentially frustrating efforts to control wild pig numbers. Conducting studies such as the present one can help state wildlife managers understand whether tolerance for wild pigs among hunters is growing and whether additional policy approaches and/or outreach efforts are needed.

Sampling and Data Collection

Data for this study were collected using an online survey (Appendix A) administered via Qualtrics online survey platform (Provo, Utah). The sample was provided by the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (ADCNR) and consisted of all individuals, both resident and nonresident, who purchased an Alabama hunting license for the 2020–2021 hunting year and had an e-mail address associated with their records (n = 33,714). Before survey distribution, questions were tested and reviewed by a small, independent group of Alabama hunters (n = 13) and revisions were incorporated. The survey was sent to individuals via e-mail on November 3, 2021. Two reminder e-mails were sent to participants on November 17 and December 1, 2021, and the survey closed on December 28, 2021. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Auburn University (reference number: 21–418 EX 2109).

Measurement of Key Concepts

General attitudes toward wild pigs were measured by asking respondents, “Overall, do you think it’s more harmful or beneficial to have wild pigs in Alabama?” Attitudes were measured on a 5-point scale, with 1 = “very harmful” and 5 = “very beneficial.” We followed a rational-realist approach to operationalizing general attitudes whereby a single item may be used to measure constructs that are double concrete (i.e., when the item used is clear and has a singular meaning and when the object being rated is also clear and singularly identifiable) (Rossiter, Citation2011).

Wildlife acceptance capacity was measured by asking respondents to identify their preferences for future changes to the wild pig population size in the state of Alabama, on a scale of 1 to 6, with 1 = “completely removed” and 6 = “increased greatly” (McLean et al., Citation2021).

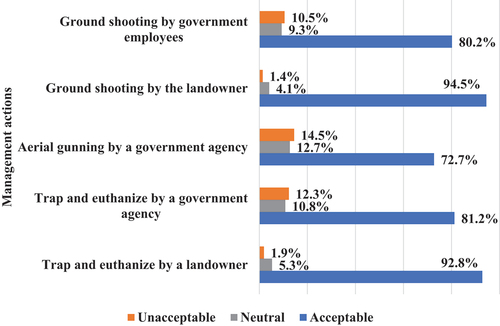

Acceptability of management actions of wild pigs was measured by asking respondents to rate the level of acceptability of using five lethal management actions to control wild pigs in Alabama. They included trapping and euthanizing by a landowner, trapping and euthanizing by a government agency, aerial gunning by a government agency, ground shooting by the landowner or the landowner’s employee/contractor, and ground shooting by government employees. All government-provided actions included the qualifier “with the permission of the landowner.” Acceptability of management actions was measured on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 = “completely unacceptable” and 5 = “completely acceptable” (Jaebker et al., Citation2021).

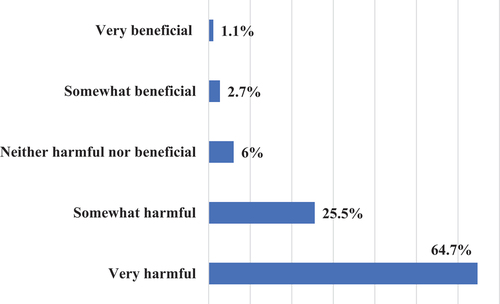

Following Bruskotter et al. (Citation2015), prior behaviors were measured by asking respondents whether they had engaged in three policy-relevant behaviors (i.e., “yes” or “no”). To understand prior supportive (i.e., tolerant) behaviors, we asked respondents if they had 1) contacted agency personnel or an elected official to voice support for maintaining wild pig populations in Alabama; 2) written a post on social media or a letter to their newspaper relating to the benefits of having wild pigs in Alabama; and 3) donated to or joined an organization that supports maintaining or conserving wild pigs in Alabama in the past two years. The same three behaviors were used to measure prior oppositional (i.e., intolerant) behaviors, except they emphasized the support or need for reducing wild pig populations in Alabama (e.g., contacted agency personnel or an elected official to voice support for reducing or eliminating wild pig populations in Alabama). The index of prior oppositional behaviors was then subtracted from the index of prior supportive behaviors to create a single composite measure of prior behaviors.

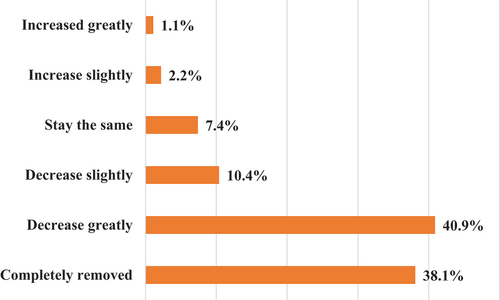

Behavioral intentions were measured similarly to prior behaviors. Respondents were asked to estimate their likelihood of engaging in each of the same six, policy-relevant behaviors on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 = “very unlikely” and 5 = “very likely.” An index for supportive behavioral intentions was created from three statements highlighting support for maintaining wild pig populations, and an index for oppositional behavioral intentions was created from the remaining statements emphasizing support for reducing or eliminating wild pig populations in Alabama. A summary measure of behavioral intentions was then created by combining these indices (i.e., supportive behavioral intentions minus oppositional behavioral intentions).

Data Analyses

We analyzed data using SPSS (Chicago, Illinois). We first conducted a reliability analysis to examine the internal consistency of the acceptability of management actions scale. If a scale yielded a Cronbach’s alpha (α) greater than 0.65, indicating acceptable measurement reliability (Vaske, Citation2008), we computed a composite score by averaging responses for all items comprising the scale. We did not seek to determine the reliability of our composite behavioral measures because we assumed that these behaviors were distinctly different and likely required varying aptitudes and incentives to carry out (Bruskotter et al., Citation2015). We then calculated descriptive statistics (frequencies, means, and standard deviations) for each tolerance measure to identify general patterns across each measure. Following Bruskotter et al. (Citation2015), we calculated Pearson’s correlation (r) or point-biserial correlation (rpb) as measures of association between each cognitive measure to assess their degree of convergent validity with one another, and between each cognitive measure and summary indices representing (a) prior supportive behaviors, (b) prior oppositional behaviors, (c) all prior behaviors, (d) supportive behavioral intentions, (e) oppositional behavioral intentions, and (f) all behavioral intentions to assess the strength of association with each cognitive measure. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used when comparing two continuous variables, while the point-biserial correlation coefficient was used when comparing one continuous variable against a dichotomous variable. We used criteria specified in the literature to denote minimal, typical, and substantial effect sizes for practical significance (r = .10, .30, .50, respectively, and rpb = .10, .243, .371, respectively) and degree of convergent validity and strength of predictive association (i.e., a substantial correlation provides evidence of high predictive association and/or convergent validity) and used an alpha level of p < .05 for statistical significance (Vaske, Citation2008).

Results

Of the 33,716 questionnaires administered, 1,681 were undeliverable and 2,751 were returned, yielding an overall response rate of 8.6%. Approximately 86% of respondents were Alabama residents, 95% were white, 93.5% were male, and 52% had completed an associate degree or higher. The mean age of respondents was 52, and the median age was 53. The demographics of our sample were largely representative of other U.S. hunters according to the most recent census provided by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service USFWS (Citation2016). The mean age of all licensed hunters in the United States was 52, and 89% were male, indicating that our sample had a slightly greater proportion of males than the study population. While we lacked the resources to measure nonresponse bias directly, we used an extrapolation method to test for nonresponse bias (Lindner et al., Citation2001). In doing so, respondents were divided into two equal groups of early and late responders, and paired t-tests were used to assess any statistical differences between the two groups on variables of interest. We found some statistical differences (p < .05), but effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were insignificant (i.e., d < .20), suggesting that there was no practical significance (Vaske, Citation2008). The variables were 1) general attitudes (t = −3.071, p = .002, d = −.086), 2) WAC (t = −3.457, p < .001, d = −.097), 3) acceptability of management actions composite measure (t = 2.774, p = .006, d = −.087), 4) prior behaviors composite measure (t = −1.823, p = .069, d = −.055), and 5) behavioral intentions composite measure (t = −2.585, p = .010, d = −.080). Using the extrapolation method, we did not find sufficient evidence to suggest there was nonresponse bias.

Descriptive Statistics of Cognitive and Behavioral Measures

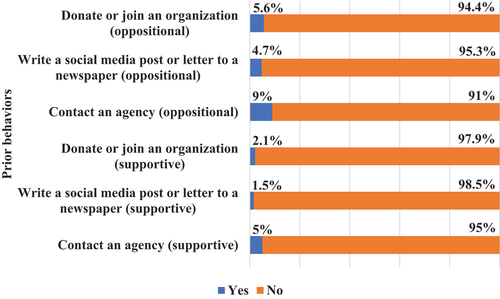

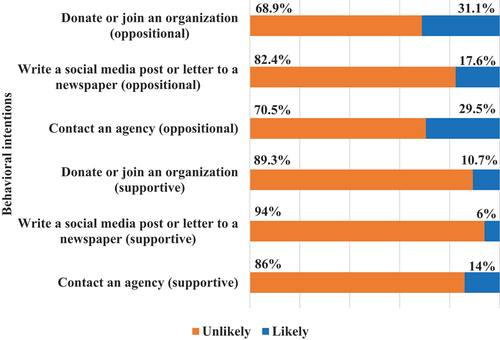

Reliability analysis of the management actions acceptability scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.85) supported the creation of a mean composite scale (M = 4.48, SD = .81). The cognitive measures of tolerance showed that respondents had largely negative attitudes toward wild pigs (M = 1.50, SD = .81; ), preferred to see a decrease in the number of wild pigs in Alabama (M = 1.98, SD = 1.08; ), and were accepting of lethal wild pig management actions (). For example, the analysis of frequencies indicated that the most acceptable management action was ground shooting by a landowner or the landowner’s employee/contractor; 95% of respondents found it somewhat or completely acceptable (M = 4.80, SD = .62). The least acceptable method was aerial gunning by a government agency with the permission of the landowner, with 73% finding it somewhat or completely acceptable (M = 4.11, SD = 1.32).

Figure 1. The frequency of response options for the general attitude question: “overall, do you think it’s more harmful or beneficial to have wild pigs in Alabama?”.

Figure 2. The frequency of response options for the wildlife acceptance capacity (WAC) question: “what change would you like to see in wild pig population numbers in Alabama?”.

Figure 3. The frequency of response options for the acceptability of management actions question: “how acceptable is it to you that each of the following wild pig control methods are used in Alabama?”Footnote1.

Regarding the behavioral measures, few respondents reported having engaged in prior supportive or oppositional behaviors in the past two years (). In total, 7% of respondents reported having engaged in at least one supportive behavior, and 14% of respondents reported having engaged in at least one oppositional behavior during the previous 2 years. In terms of specific supportive behaviors, contacting an agency to voice support for maintaining wild pig populations was the most common among respondents (5%), while the most common oppositional behavior was contacting an agency to voice support for reducing wild pig populations (9%). Concerning behavioral intentions, few respondents indicated they would be likely to engage in supportive or oppositional-related behaviors in the next year (). More commonly, behavioral intentions reflected respondents’ opposition to wild pigs on the landscape. For example, about 31% of respondents reported they would be somewhat or very likely to donate or join an organization that supports reducing or eliminating wild pigs in Alabama, (M = 2.19, SD = 1.51). Similarly, about 30% reported it would be somewhat or very likely that they would contact agency personnel or an elected official to voice support for reducing or eliminating wild pig populations in Alabama (M = 2.18, SD = 1.13).

Correlations Between Cognitive and Behavioral Measures of Tolerance

The three cognitive measures exhibited significant, typical (r and rpb = .30 and .243, respectively) to substantial (r and rpb = .50 and .371, respectively) relationships with one another. General attitudes toward wild pigs and WAC were substantially positively correlated (r = .68, p < .001), indicating a high degree of convergent validity and reflecting that respondents who had held more positive attitudes toward wild pigs preferred that wild pig populations increase. Conversely, general attitudes and WAC were typically negatively correlated with acceptability of management actions (r = −.38, p < .001 and r = −.41, p < .001, respectively), indicating that respondents who held positive attitudes toward wild pigs and wanted wild pig population increases were less accepting of using lethal actions to manage wild pigs.

Prior behaviors exhibited minimal (r and rpb = .10) to insignificant (r and rpb nearing zero) relationships with general attitudes, WAC, and management action acceptability (). This was reflected in all relationships with the single-item measures, summary measures, and overall composite measures. Behavioral intentions exhibited typical (r =.30 and rpb = .243) to insignificant relationships with general attitudes, WAC, and management action acceptability (). There were typical negative relationships between general attitudes and the two individual oppositional intentions items “contact agency to voice support for reducing wild pig populations” (r = −.30, p < .001) and “donate or join an organization that supports reducing wild pig populations” (r = −.30, p < .001), indicating that respondents who held more positive attitudes toward wild pigs were less likely to engage in either behavior. There was also a typical positive relationship between general attitudes and the composite measure of behavioral intentions (r = .35, p < .001). Moreover, there were typical negative relationships between WAC and the two individual oppositional intentions items “contact agency to voice support for reducing wild pig populations” (r = −.32, p < .001) and “donate or join an organization that supports reducing wild pig populations” (r = −.33, p < .001), indicating that respondents who preferred greater wild pig populations were less likely to engage in either behavior. Lastly, there was a typical negative relationship between WAC and the summary measure of supportive intentions (r = −.32 p < .05) and a typical positive relationship between WAC and the composite measure of behavioral intentions (r = .39, p < .001).

Table 1. Correlations between cognitive and behavioral measures of tolerance.

Discussion

This study investigated the convergent validity of three different but commonly employed cognitive measures of tolerance and the strength of association between the cognitive measures and relevant prior behaviors and behavioral intentions. As with Bruskotter et al. (Citation2015), we found substantial, significant relationships between general attitudes and WAC, indicating a high degree of convergent validity, and suggesting that both measures are similar and highly related psychological aspects of tolerance. However, the relationships between acceptability of management actions and each of the other two cognitive measures, while significant, had only a typical effect size and represented too low a degree of convergence for the measures to serve as equally suitable proxies for tolerance. In this regard, Carlson and Herdman (Citation2012) advise that the use of alternative measures or proxies with convergent validities below r = .50 or rpb = .371 should be avoided because they can result in large differences in findings. Thus, while still practically relevant to the tolerance concept (Delie et al., Citation2022; Morzillo & Needham, Citation2015), acceptability of management actions may not be effectively interchangeable with the other cognitive measures for purposes of measuring hunters’ tolerance for wild pigs. One could imagine that an individual could have a negative attitude toward wild pigs yet oppose lethal control for moral or ethical reasons (a less likely scenario with hunters) or oppose lethal control because they prefer to have more wild pigs to hunt (a more likely scenario with some hunters).

In contrast to Bruskotter et al. (Citation2015), our study did not find evidence of a strong association between cognitive measures of tolerance and the measures of past behaviors and behavioral intentions that we adapted from Bruskotter et al. (Citation2015). Our analyses revealed that most relationships between our cognitive measures (most notably general attitudes and WAC) and our behavioral measures were minimal and often insignificant. This speaks in part to the complexity of the attitude-behavior relationship that has been extensively debated on account of the inconsistency of attitudes predicting behaviors (e.g., Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation2005; Fazio & Zanna, Citation1978; LaPiere, Citation1934). In this regard, Bruskotter et al. (Citation2015) note that prior studies have found greater consistency between attitudes and behaviors when the study population was highly involved in the relevant issue and/or believed it was important. They acknowledge that the strong association they found between cognitive and behavioral measures of wolf tolerance may not have been representative of the public given their sample comprised of visitors to a wildlife blog with frequent posts about wildlife management issues (Bruskotter et al., Citation2015). This limitation may partly explain why our results differed. Although our respondents may have been more knowledgeable or interested in wild pigs than the general public, most were likely not part of the issue public – i.e., the segment of the population that follows an issue closely and engages in efforts to influence policymaking (Key, Citation1963).

For many generalist hunters (and the public more broadly), we suspect that (in)tolerance for wild pigs is associated with passivity when it comes to policy-focused behaviors and behavioral intentions. While possibly undesirable, neither the species’ presence nor its population size likely reaches a threshold that would incentivize most individuals to engage in policy-relevant behaviors. We focused on policy-related behaviors because they were measured by Bruskotter et al. (Citation2015), and we wanted to test their findings in a different context. We may have found stronger relationships with the cognitive measures if our behavioral measures better reflected hunter (in)tolerance for wild pigs. It should be noted, however, that the individuals with the greatest tolerance for wild pigs are likely to be those who enjoy hunting and/or consuming them (Grady et al., Citation2019; McLean et al., Citation2021). This raises a practical difficulty in trying to measure both tolerant and intolerant behaviors for wild pigs. While killing an animal in most contexts would be associated with intolerance, in the case of wild pigs, it often may be associated with a desire for a stable or even larger population of the species for future hunting opportunities. Moreover, asking hunters whether they transport and release wild pigs is problematic because these behaviors are now illegal activities in most states, and study participants may be reluctant to report their participation in such activities. As Bruskotter et al. (Citation2015) note, in study contexts where respondents may not be inclined to report their behaviors, cognitive dimensions of tolerance may be more appropriate to measure. Regardless, translocating wild pigs is likely a fringe activity among a small subset of hunters (Grady et al., Citation2019), and we would not expect to find a strong association between that behavior and cognitive measures of wild pig tolerance in a study that sampled a generalist population of hunters. We therefore believe it may be challenging to identify behaviors and behavioral intentions that have a meaningful predictive association with cognitive measures of wild pig tolerance.

More broadly, we believe this study raises interesting questions about the nature of the tolerance concept and how it presents in contexts involving a nonnative, invasive species that is valued primarily as a recreational and food resource. If one conceptualizes tolerance as WAC, then as previously noted, those exhibiting the greatest tolerance for wild pigs also likely enjoy engaging in extractive uses of the species. Moreover, such a manifestation of tolerance is not necessarily inconsistent with holding a generally negative attitude toward the species, as one may view wild pigs as a pest or nuisance but also recognize their recreational or subsistence value and wish to maintain at least a small population for hunting and consumption. In unreported data from McLean et al. (Citation2021), approximately 80% of surveyed Texas hunters agreed that wild pigs in Texas were a nuisance, yet 50% also agreed that wild pigs were a valuable resource for recreation, meat, or income, and most (80%) preferred that wild pig populations not be eliminated. We speculate that had we surveyed only hunters who exclusively or primarily hunted wild pigs in Alabama (i.e., those with the greatest reliance on the species), we most likely would not have found as strong of a correlation between general attitudes and WAC. More fundamentally, if a person is willing to coexist with the species up to some threshold, but only to hunt or consume it, is that person “tolerant” of the species as the concept is commonly understood and applied? Answering the question is made more difficult on account of the many cognitive and behavioral phenomena associated with tolerance, though we believe that if one conceptualizes tolerance as WAC, the answer is probably “yes.”

As the foregoing suggests, the most appropriate measures of tolerance likely vary by species and respondent group, which makes systematic development of the concept challenging. Part of the challenge stems from the various indicators that have been associated with the concept in the literature and which may or may not be strongly associated with one another depending on the context. In effect, we believe the tolerance concept has become an umbrella term for multiple related but distinct concepts or measures, such as WAC, general attitudes, and acceptance of management measures. Further, we propose there are benefits to, for example, expressly using the WAC concept when measuring respondents’ preferences for wildlife population sizes and not purporting to measure tolerance when one is, in fact, measuring general attitudes toward wildlife or the acceptability of wildlife management actions. This is especially true for applied research. Depending on the context and one’s objectives, some measures may be more useful or appropriate than others. If one’s goal is to provide information to wildlife managers who wish to understand whether the population level of a species in an area may generate conflict or cause individuals to take adverse actions against a species, WAC would likely be the most appropriate tolerance-related measure. If, on the other hand, wildlife managers are more interested in knowing the types of actions individuals may take to impact a wildlife population positively or negatively, behavioral measures would be more useful. Use of the broader tolerance concept may be more appropriate when researchers are focused on the development of theory, such as in studies that investigate how different cognitive and behavioral measures associated with the concept are correlated with one another and present in various contexts.

In terms of applied findings, we found that while hunters had largely negative attitudes toward wild pigs, roughly half of them (51%) preferred that wild pig populations be decreased but not completely eliminated, while 7% wanted the population size to stay the same and 3% wanted it to increase. In a conservation context, this level of tolerance would be considered very low and potentially troubling. In the context of wild pig management, the findings are somewhat troubling for a different reason – i.e., efforts to eradicate wild pigs may be met with resistance if more than half of Alabama hunters prefer that wild pigs continue to exist in the state. Large majorities did, however, find all lethal management actions to be acceptable, although those carried out by landowners received higher scores than those carried out by agency personnel. We note that these findings are consistent with studies that examined hunters’ tolerance and management preferences for wild pigs in Texas (Jaebker et al., Citation2021; McLean et al., Citation2021).

While our study provided empirical evidence on the topic of attitude-behavior consistency in the context of Alabama hunters’ tolerance for wild pigs, future research would do well to expand on and speak to certain limitations in our study. As previously noted, the behavioral items we used in our questionnaire may not have provided the most relevant measures of tolerant and intolerant behaviors of hunters toward wild pigs, and we described some of the challenges in trying to measure more appropriate behaviors. We nevertheless believe it would be a worthwhile endeavor to develop and test other behavioral items in this context to determine whether behaviors and behavioral intentions exist that are strongly correlated with cognitive measures of tolerance toward wild pigs. As well, we believe there is value in using the policy-related behavioral items in studies of other stakeholders’ tolerance for wild pigs. Landowners and agricultural producers, for example, likely incur the most losses to wild pigs and may have the greatest incentives to contact agency personnel in an effort to seek relief from the species. We might therefore expect to find a stronger correlation between the cognitive and behavioral measures of tolerance that we used with these stakeholder groups. We also suggest that future research should operationalize the general attitude concept with multiple questionnaire items to determine whether it could potentially improve its predictive ability and the strength of its association with other measures (Diamantopoulos et al., Citation2012). Finally, we recognize that measuring the acceptability of management actions without more context is often not the best approach, as acceptability of management actions may depend on the harm that wildlife pose, among other considerations. Brenner and Metcalf (Citation2020), for example, posit that measuring reaction norms (i.e., the acceptability of wildlife management actions in situation-specific scenarios) can reveal more about human acceptance of specific wildlife behaviors, population levels, and management actions. As evidenced by the high acceptability scores for management actions in this study, lethal control of wild pigs does not appear to be particularly controversial among hunters, and we may not have found much variability in these scores had we included a more situation-specific context. Nevertheless, in studies involving the public or other stakeholder groups, doing so may be warranted and may yield more substantial correlations between management action acceptability and the other cognitive and behavioral measures of tolerance.

In conclusion, this study highlights certain needs and issues for the research agenda on the tolerance concept. Chief among them is empirical research that clarifies how the various cognitive and behavioral dimensions associated with the concept are present in different wildlife management contexts. This includes research that furthers our understanding of when and how these measures are correlated with one another. We believe that efforts to decompose the tolerance concept and analyze the relationships among its posited indicators in different contexts could generate a more nuanced theory and provide greater conceptual clarity. This could lead to more appropriate measurements of tolerance-related needs in applied contexts, allowing managers to understand better the public’s preferences for living alongside wildlife populations.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this publication are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank C. Sykes, K. Gauldin, and W. McCullers with the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources for their support and assistance with this study. We also thank Auburn University, the National Feral Swine Damage Management Program, and the survey respondents for making this research possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author, H. Ellis, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Percentages for “unacceptable” encompass “somewhat unacceptable” and “completely unacceptable” response options. Similarly, percentages for “acceptable” encompass “somewhat acceptable” and “completely acceptable” response options.

References

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (2005). The influence of attitudes on behavior. In D. Albarracín, B. T. Johnson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), The handbook of attitudes (pp. 173–221). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Brenner, L. J., & Metcalf, E. C. (2020). Beyond the tolerance/intolerance dichotomy: Incorporating attitudes and acceptability into a robust definition of social tolerance of wildlife. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 25(3), 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2019.1702741

- Bruskotter, J. T., & Fulton, D. C. (2012). Will hunters steward wolves: A comment on Treves and Martin. Society and Natural Resources, 25(1), 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2011.622735

- Bruskotter, J. T., Singh, A., Fulton, D. C., & Slagle, K. (2015). Assessing tolerance for wildlife: Clarifying relations between concepts and measures. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 20(3), 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2015.1016387

- Bruskotter, J. T., & Wilson, R. S. (2014). Determining where the wild things will be: Using psychological theory to find tolerance for large carnivores. Conservation Letters, 7(3), 158–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12072

- Carlson, K. D., & Herdman, A. O. (2012). Understanding the impact of convergent validity on research results. Organizational Research Methods, 15(1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428110392383

- Caudell, J. N., Dowell, E., & Welch, K. (2016). Economic utility for the anthropogenic spread of wild hogs. Human-Wildlife Interactions, 10(2), 9.

- Cleary, M., Joshi, O., & Fairbanks, W. S. (2021). Factors that determine human acceptance of black bears. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 85(3), 582–592. https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.21999

- Decker, D. J., & Purdy, K. G. (1988). Toward a concept of wildlife acceptance capacity in wildlife management. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 16(1), 53–57.

- Delie, J., Edwards, J., & Biedenweg, K. (2022). Using psychometrics to characterize the cognitive antecedents of tolerance for black bears. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 28(5), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2022.2077481

- Diamantopoulos, A., Sarstedt, M., Fuchs, C., Wilczynski, P., & Kaiser, S. (2012). Guidelines for choosing between multi-item and single-item scales for construct measurement: A predictive validity perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 434–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0300-3

- Fazio, R. H., & Zanna, M. P. (1978). On the predictive validity of attitudes: The roles of direct experience and confidence. Journal of Personality, 46(2), 228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1978.tb00177.x

- Fern, M., Barlow, R., Slootmaker, C., Kush, J., Shwiff, S., Teeter, L., & Armstrong, J. (2021). Economic estimates of wild hog (Sus scrofa) damage and control among young forest plantations in Alabama. Small-Scale Forestry, 20(4), 503–516. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11842-021-09478-5

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2010). Predicting and changing behavior. Psychology Press.

- Frank, B. (2016). Human-wildlife conflicts and the need to include tolerance and coexistence: An introductory comment. Society & Natural Resources, 29(6), 738–743. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2015.1103388

- Frank, B., & Glikman, J. A. (2019). Human–Wildlife Interactions: Turning Conflict into Coexistence. In B. Frank, J. A. Glikman, &S. Marchini (Eds.), Conservation Biology 23 (pp. 1–19). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Gigliotti, L., Decker, D. J., & Carpenter, L. H. (2000). Developing the wildlife stakeholder acceptance capacity concept: Research needed. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 5(3), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871200009359189

- Grady, M. J., Harper, E. E., Carlisle, K. M., Ernst, K. H., & Shwiff, S. A. (2019). Assessing public support for restrictions on transport of invasive wild pigs (sus scrofa) in the United States. Journal of Environmental Management, 237, 488–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.02.107

- Gross, S. J., & Niman, C. M. (1975). Attitude-behavior consistency: A review. Public Opinion Quarterly, 39(3), 358–368. https://doi.org/10.1086/268234

- Hosaka, T., Sugimoto, K., Numata, S., & Ito, E. (2017). Effects of childhood experience with nature on tolerance of urban residents toward hornets and wild boars in Japan. PLoS One, 12(4), e0175243. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175243

- Inskip, C., Carter, N., Riley, S., Roberts, T., MacMillan, D., & Goodrich, J. (2016). Toward human-carnivore coexistence: Understanding tolerance for tigers in Bangladesh. PLoS One, 11(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145913

- IUCN. (2023). IUCN SSC guidelines on human-wildlife conflict and coexistence (First ed.).

- Jaebker, L. M., Teel, T. L., Bright, A. D., McLean, H. E., Tomeček, J. M., Frank, M. G., Shwiff, S. A., Carlisle, K. M., & Carlisle, K. M. (2021). Social identity and acceptability of wild pig (sus scrofa) control actions: A case study of Texas hunters. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 27(6), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2021.1967525

- Kansky, R., Kidd, M., & Fischer, J. (2021). Understanding drivers of human tolerance towards mammals in a mixed-use transfrontier conservation area in southern Africa. Biological Conservation, 254, 108947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108947

- Kansky, R., Kidd, M., & Knight, A. T. (2016). A wildlife tolerance model and case study for understanding human-wildlife conflicts. Biological Conservation, 201, 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.07.002

- Kansky, R., & Knight, A. T. (2014). Key factors driving attitudes towards large mammals in conflict with humans. Biological Conservation, 179, 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.09.008

- Key, V. O. (1963). Public opinion and American democracy. Knopf.

- LaPiere, R. T. (1934). Attitudes vs. actions. Social Forces, 13(2), 230–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/2570339

- Lewis, M. S., Pauley, G., Kujala, Q., Gude, J. A., King, Z., & Skogen, K. (2012). In HD unit research summary (Report No. 34). Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks.

- Lindner, J. R., Murphy, T. H., & Briers, G. E. (2001). Handling nonresponse in social science research. Journal of Agricultural Education, 42(4), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2001.04043

- Lischka, S. A., Riley, S. J., & Rudolph, B. A. (2008). Effects of impact perception on acceptance capacity for white‐tailed deer. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 72(2), 502–509. https://doi.org/10.2193/2007-117

- Lischka, S. A., Teel, T. L., Johnson, H. E., & Crooks, K. R. (2019). Understanding and managing human tolerance for a large carnivore in a residential system. Biological Conservation, 238, 108189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.07.034

- McKee, S., Anderson, A., Carlisle, K., & Shwiff, S. A. (2020). Economic estimates of invasive wild pig damage to crops in 12 US states. Crop Protection, 132, 105105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2020.105105

- McLean, H. E., Teel, T. L., Bright, A. D., Jaebker, L. M., Tomeček, J. M., Frank, M. G., Connally, R. L., Shwiff, S. A., & Carlisle, K. M. (2021). Understanding tolerance for an invasive species: An investigation of hunter acceptance capacity for wild pigs (sus scrofa) in Texas. Journal of Environmental Management, 285, 112143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112143

- Morzillo, A. T., & Needham, M. D. (2015). Landowner incentives and normative tolerances for managing beaver impacts. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 20(6), 514–530. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2015.1083062

- Pooley, S., Barua, M., Beinart, W., Dickman, A., Holmes, G., Lorimer, J., Loveridge, A. J., Macdonald, D. W., Marvin, G., Redpath, S., Sillero-Zubiri, C., Zimmermann, A., & Milner‐Gulland, E. J. (2017). An interdisciplinary review of current and future approaches to improving human–predator relations. Conservation Biology, 31(3), 513–523. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12859

- Rainer, D. 2022. WFF breaks New ground with night shoot. In Outdoor Alabama, Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved https://www.outdooralabama.com/articles/wff-breaks-new-ground-night-shoot

- Rossiter, J. R. (2011). Measurement for the social sciences: The C-OAR-SE method and why it must replace psychometrics. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Struebig, M. J., Linkie, M., Deere, N. J., Martyr, D. J., Millyanawati, B., Faulkner, S. C., Le Comber, S. C., Mangunjaya, F. M., Leader-Williams, N., McKay, J. E., & St. John, F. A. V. (2018). Addressing human-tiger conflict using socio-ecological information on tolerance and risk. Nature Communications, 9(1), 3455. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05983-y

- Sutherland, W., Adams, W., Aronson, R., Aveling, R., Blackburn, T., Broad, S., Ceballos, G., Côté, I. M., Cowling, R. M., Da Fonseca, G. A. B., Dinerstein, E., Ferraro, P. J., Fleishman, E., Gascon, C., Hunter, M., Hutton, J., Kareiva, P., Kuria, A., Macdonald, D. W., and Watkinson, A. R. (2009). One hundred questions of importance to the conservation of global biological diversity. Conservation Biology, 23(3), 557–567. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01212.x

- Treves, A. (2012). Tolerant attitudes reflect an intent to steward: A reply to Bruskotter and Fulton. Society & Natural Resources, 25(1), 103–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2011.621512

- USFWS (US Fish and Wildlife Service). (2016). National survey of fishing, hunting, and wildlife‐associated recreation (FHWAR): 2016. United States Fish and Wildlife Service.

- Vaske, J. J. (2008). Survey research and analysis: Applications in parks, recreation, and human dimensions. Venture Publishing, Incorporated.

- Wald, D. M., & Jacobson, S. K. (2013). Factors affecting student tolerance for free-roaming cats. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 18(4), 263–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2013.787660

- Zimmermann, A., Walpole, M. J., & Leader-Williams, N. (2005). Cattle ranchers’ attitudes to conflicts with jaguar (Panthera onca) in the pantanal of Brazil. Oryx, 39(4), 406–412. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605305000992