ABSTRACT

Background: The need for increased expertise in evidence-based medicine and concerns about the decreasing numbers of physician-scientists have underscored the need for promoting and encouraging research in medical education. The critical shortage of physician-scientists has assumed a dimension demanding a coordinated global response. This systematic review examined the perceptions of medical students regarding research during undergraduate medical school from a global perspective.

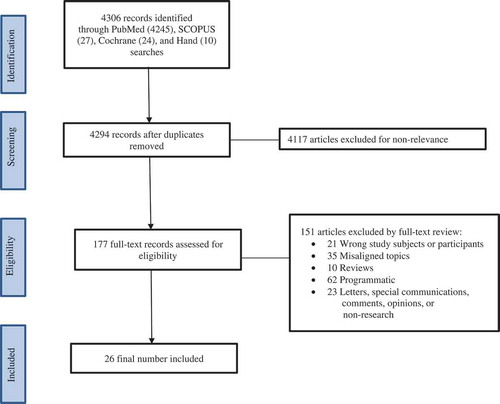

Methods: Articles for this review were searched using PubMed, SCOPUS and Cochrane. Studies published within the last 10 years of the start date of the study that met specified criteria were included. Identified articles were initially screened by title as well as keywords and their abstracts were further screened to determine relevance. Full-text of screened articles were read for validation prior to inclusion.

Results: A total of 26 articles from the literature met the set criteria for final inclusion. Contents of the abstracts and corresponding full-text articles were analyzed for themes on the research perspectives of medical students. The themes derived comprised: research interest, physician-scientist decline and shortage, responses to physician-scientist shortage, curriculum issues, skills (motivation and self-efficacy), research needs, socioeconomic and cultural issues, and barriers.

Conclusion: Despite the wide variations in medical education systems worldwide, the perspectives of medical students on research in undergraduate medical education shared many common themes. Globally, medical students underscored the necessity and importance of research in medical education as reflected by many students reporting positive attitudes and interest in research endeavors. Moreover, a worldwide consensus emerged regarding the decline in the numbers of physician-scientists and the necessity for a reversal of that trend. Various barriers to research engagement and participation were highlighted.

Introduction

Two main drivers necessitating research during medical education have been the need for increased evidence-based medical practice and bench-to-bedside translational research with physician-scientists/researchers driving this process [Citation1–Citation6]. Hence, increasingly, the need for research as a critical component of modern medical education has not only gained currency but also urgency [Citation2,Citation3]. During undergraduate medical education, research instruction and involvement often provides the first opportunity for a medical student to gain exposure to research and participate in it. Medical students who engage in research learn how to formulate cogent thoughts from the generation of research ideas through study implementation to dissemination. Furthermore, they would have applied the scientific process in what they did, what they found, and how to report and explain such findings with rigorous detail and accuracy [Citation3,Citation7]. Such early immersions can contribute to the development of lasting habits of scientific thought and profound dispositions toward critical thinking [Citation2,Citation3], a vital aptitude that enhances success in the practice of medicine and engenders a crucial mentality that deserves early nurturing [Citation1–Citation3]. The importance of evidence-based medicine has meant that physicians are expected to be skilled and knowledgeable in the use of research and scientific methods of enquiry as applied to medical practice.

Indeed, clinician literacy in research improves critical thinking in guiding clinical judgement – necessary ingredients for the effective application of evidence-based medicine [Citation7]. The ability to competently locate and critically appraise the appropriate medical literature, interpret volumes of data, integrate, and translate those for use in clinical situations is invaluable to medical practice [Citation7,Citation8]. The marriage between the clinical competence of a physician and the independent literature-based clinical evidence for informed decision-making could spell the difference between life and death of patients under potentially time-dependent conditions [Citation7,Citation9]. Such skills underscore the importance of the acquisition of research competencies and its crossover to the practice of evidence-based medicine [Citation1–Citation3].

The other related factor that undergirds the need for intensification of clinical research in medical education has been the continued decline in the numbers of physician-scientists (also sometimes referred to as clinician-researchers). Many studies have unequivocally shown that the numbers of physician-scientists have been in decline for many years [Citation2,Citation4–Citation6,Citation10–Citation12]. In 2003, the number of physicians involved primarily in research was 1.8% compared to 4.6% in 1985 [Citation6]. Another study found a lower percentage of 1.6% in 2011 compared to 3.6% in 1982 [Citation11]. These alarming statistics about the decrease in the number of physician-scientists have not abated since the over four decades when it first received topical attention [Citation5,Citation6]. Indeed, the decline in numbers and scarcity of physician-scientists have assumed a global dimension. It is no longer an isolated issue confined only to some specific geographical regions of the world, it has become a worrisome issue with a global reach that requires concerted attention for redress [Citation2,Citation4].

Despite the expressed need and importance of clinical research, research training during undergraduate medical education in many countries is still inadequate, uncoordinated, constrained, and riddled with many difficulties [Citation1,Citation13]. Research instruction has often been for fulfilling required competencies of professionalism and continuing education. Furthermore, in some other instances, research in medical education is used for purposes of satisfying accreditation requirements. Key questions would be how do medical students perceive research during undergraduate medical training? What are their attitudes toward research? Do they perceive or understand research competencies as a critical component of their evidence-based knowledge? Does research appeal to them for purposes of evidence-based practice or contemplation to pursue a physician-scientist career in the future? Hence, it is important to understand the dynamics of the two drivers of research perspectives of medical students during medical school through a global prism. However, no known study has synthesized the available literature to highlight the global scope of the problems and the perspectives that pertained to it.

This systematic literature review synthesized the contemporary global perspectives (comprising perceptions, attitudes, beliefs, and dispositions) of medical students regarding research during their undergraduate training. It examined the ways in which medical students shared similar or different perspectives toward research during undergraduate medical education within a global context. Specific factors associated with their research perspectives and those with interest in a physician-scientist career path were explored. A deliberate delineation was made for comparative and contrast purposes between the U.S. landscape relative to the rest of the world for deeper insights, understanding, and search for solutions of emergent issues.

Methods

Search

The articles were obtained from PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane databases covering a 10-year timeframe going back from 9/29/2007 to 9/29/2017 when the study was started. This search window was necessitated by using the start date of the study as the cutoff point so that the search was stabilized while capturing contemporary trends on the topic with the preceding 10 years as a prism. The search included title, abstracts, and keywords of studies from the global medical education literature. The search terms/keywords or phrases used for this review were as follows: Research, medical students, physician-scientist, career choices, osteopathic medical students, osteopathic medicine, perceptions, attitudes, motivations, and interests. The Boolean Operators ‘or’ and ‘and’ were used to expand and narrow the searches to include all the pertinent publications within the period under review. The use of osteopathic medical students in the key-word search was deliberate to ensure that, as a minority part of medical education in the U.S., its perspectives were represented as much as possible in the final literature. Only articles published in English were included and the search was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were excluded if they: 1) were not written in English, 2) involved program evaluations such as changes in student perceptions post-implementation of a specific curriculum or educational program, 3) combined data of medical students with physician or with other non-medical degree populations without clear distinction of data, 4) were Meta-analyses and Systematic Reviews older than 10 years as well as literature that mixed domestic and international medical student populations and, 5) were published letters to an editor, special communications, and opinions not based on methodology, results, and conclusions of a study.

Study selection and process

Using the eligibility criteria, the preliminary list of literature was compiled by CS, BT, and GB who read the titles and abstracts of articles that were returned by the keyword search and the original number was reduced to those that met the inclusion criteria (See Search Strategies in Appendix). The abstracts of the subset of studies that met the criteria were read in entirety to determine relevance by CS, BT, KVF, and SK. Upon reading of the abstracts, if relevance was suspected or in question, the entirety of the article was read to determine its inclusion/exclusion. GD provided a global oversight by coordinating the consensus process as an independent eye. Articles that were not fully agreed upon for inclusion were discussed in a series of consensus building meetings until a consensus among the authors was reached.

Data analysis

A quantitative analysis of the data obtained was purposefully not performed. This was because of difficulty in functional comparisons due to the variety of methods used in the studies together with the variations in medical education systems globally. In this study, we gathered the following information: author, country, sampled population, perspective studied, methods, and outcomes. We adopted a non-linear, iterative process involving content analysis for themes until a saturation point was reached where no new themes emerged. Constant comparisons were made among the group of authors to reconcile opinions for a consensual conclusion on themes.

Results

shows the schematic diagram of searching the literature. The title, abstract, and keywords, English language only, and the date of the search yielded 4306 studies. A further narrowing down yielded 4294 abstracts after removing duplicates. Furthermore, after excluding articles for non-relevance, 177 abstracts were obtained. The full-texts of these were further read in entirety resulting in the final inclusion of 26 studies. Upon reading of an abstract, if relevance was in question, the entirety of the article was read again by multiple researchers to determine if it tightly met inclusion/exclusion criteria.

The studies were from 13 countries representing different regions in the developed and developing worlds, (). Majority of the articles were from Pakistan and Saudi Arabia.

Table 1. Number of studies included by country/region of origin.

provides a bibliographic summary of the studies selected for the systematic review.

Table 2. Characteristics of each article included in the study.

lists the emergent themes that characterized the global perspectives of medical students toward research during medical school.

Table 3. Common themes from global perspectives on research during medical education derived from content analysis of the abstracts/full-text articles.

These were derived from the 26 studies that were finally included as the data for the review. These themes were common across the studies within the medical education contexts of the U.S. and other countries outside the U.S. The themes derived were as follows: Research interest, physician-scientist decline and shortage, responses to the physician-scientist shortage, curriculum issues, skills (motivation and self-efficacy), research needs, socioeconomic and cultural issues, and barriers.

Discussion

Out of the 26 selected articles, 23 (89%) were from countries outside the U.S. and 3 (11%) from the U.S. One plausible explanation of this result could be that in the U.S., most studies involved the assessment (pre-post) of specific programs involving research in medical education and therefore were excluded according to the study inclusion/exclusion criteria. Another possible explanation is that the physician-scientist shortage in the U.S. had been recognized decades earlier following the 1979 seminal work of Wyngaarden [Citation11]. Ever since, the issue has been studied for decades, hence most of the perspectives were likely reported in articles published earlier than our timeframe considered in the inclusion criteria for this present study. This could indicate a positive direction in the sense that programs in the U.S. have been trying to address this problem over many decades. Moreover, the U.S. literature was replete with programmatic endeavors directed at fostering training of research savvy physicians and addressing the physician-scientist shortage.

By the exclusion criteria of this study, studies with programmatic leanings were excluded. One exception to note regarding the U.S. medical education landscape, however, is that exposure of osteopathic (DO) medical students to research is still in an early growth phase with limited data compared to their allopathic (MD) counterparts [Citation20] hence its relative over representation in the U.S. literature in this current study. According to the National Resident Matching Program match data, U.S. allopathic students lead in the number of research experiences, followed by non-U.S. international medical graduates (IMG), U.S. IMG’s, and then osteopathic medical students [Citation21–Citation23]. Although osteopathic medical research has been on the rise [Citation24], historically there has been a lack of culture promoting research [Citation25] and even today, the osteopathic medical field still lags the allopathic field in the conduct of clinical research [Citation26].

This current systematic review derived common themes that threaded through medical students’ research perspectives globally. Broad consensus was found on these themes with minor context-specific and geographic variations.

Research interest

One common strand that was found in the perspectives of research during medical education was the medical students’ expressed interest and positive attitude toward research [Citation20,Citation27,Citation28]. Overall, medical students viewed research as useful and important to their education [Citation29,Citation30]. However, motivations behind this interest varied from context to context across countries. For example, some students were interested in research to be competitive for residency [Citation4,Citation31,Citation32], enhance curriculum vitae or resumés [Citation32,Citation33], and for some international medical students to gain admission into U.S. residency programs [Citation33]. Nonetheless, the expressed interest in research did not translate into many more medical students thinking of becoming physician-scientists. Moreover, many of such students did not indicate if research engagement was to help them engage in future evidence-based practice or pursue a research career [Citation4,Citation34].

Physician-scientist: decreasing numbers and shortage

There was a near universal accord regarding the recognition of the decline and shortage of physician-scientists as a problem that demanded serious attention. The literature was replete with expressed concerns about the lack of enthusiasm on the part of budding physicians to pursue the physician-scientist career track. Indeed, although many medical students indicated the importance of research in their education, they were not favorably inclined to pursue it as a career [Citation4]. Various reasons were adduced for the lack of interest in a clinical research career path. Some of those reasons were preference for direct patient care as a clinician, lifestyle of a physician rather than a physician-scientist, diminished desire in prolonged training and accrual of extra debt, need to pay-off current student debt, difficulty in seeking extra-mural funds, lack of mentorship, and lack of interest in a scientific/research career [Citation4–Citation6].

Response to physician-scientist shortage

Recognition of the decreasing numbers of physician-scientists as well as shortages led to the adoption of measures to counter or arrest the decline. Although we excluded program-specific studies from this review, it is important to point out that some of the studies that met the inclusion criteria suggested solutions to this problem. Some of those included dual-degrees such as MD/PhD or intercalated programs (as they are referred to in some countries outside the U.S [Citation35]. Other combined programs and specialized programs were introduced by various medical colleges especially in the U.S. and Canada [Citation36].

Some of the responses were premised on the idea that medical students should be equipped with research skills. To address student needs, a multitude of solutions from different countries have been experimented to expose medical students to research, encourage participation, and develop the requisite skills to be successful. Some examples include the development of national research programs (Norway) [Citation37], voluntary immersion at individual institutions (Lebanon) [Citation38], workshops (Saudi Arabia) [Citation39] (India) [Citation40], research courses (U.S.) [Citation41], or fairs featuring keynote speakers, presentations, (Germany) [Citation42], all of which have been met with varying degrees of success.

The most common reasons for not pursuing a dual or intercalated degree option were lack of interest, social reasons, and financial reasons [Citation28,Citation35]. There was no widespread support from the students for having research training as a compulsory part of medical school curriculum. With respect to long-term career plans, just a small proportion reported interest in wanting to become physician-scientists [Citation34]. However, more students rated lifestyle and earning potential as more important factors than opportunity for research when choosing a career specialty [Citation34,Citation35].

Curriculum

There was a high-level of agreement in the literature among medical students that despite the importance of research, it often was not well represented in their curricula. Curricula were often overloaded with basic and clinical science subjects with little room for research instruction and learning. In most cases, research participation was an extra-curricular activity where students were not well prepared in the basic concepts of epidemiology, statistics, and scientific investigation [Citation41,Citation43]. Indeed, students often reported low confidence in understanding medical literature and statistical analysis. Windish et al. [Citation44], for example, surveyed 11 residency programs in the U.S. to assess biostatistics and research interpretation – the result was an average of 40% score on a multiple-choice test. Such a finding highlighted that knowledge deficits in research competencies and skills during medical school often spilled over to residency. This result was consistent with the literature elsewhere within the global context [Citation44–Citation46]. Curriculum that incorporates, enacts, and implements research during undergraduate medical education is critical because students who got trained and involved in research were more likely to continue to do research in the future [Citation36].

Skills

Many medical students lacked the skills to pursue research during undergraduate medical education [Citation47,Citation49]. This lack of skills may arise from inadequate early exposure to the basic concepts of scientific inquiry that serves to limit their later research involvement [Citation49–Citation51]. While in some countries students had research exposure before medical school, they still did not feel prepared enough to engage in research [Citation35,Citation47,Citation50]. A plausible explanation could be that the previous research experience was not targeted enough to facilitate their participation in applied research during medical school. This lack of skills perhaps resulted in low motivation and lack of self-efficacy among many students [Citation47].

Research needs

Medical students worldwide expressed needs that, if addressed, would facilitate their participation and engagement in research during medical school. These needs included, mainly but not exclusively, research training, curriculum enhancements, time availability, and availability of infrastructure for research. Indeed, these needs coincided with some of the other themes that were gleaned from the review. Some institutions accommodate students by allowing research to be conducted during their spare time using technology [Citation46], or through the implementation of a more flexible preclinical curriculum [Citation52].

Socio-economic and cultural

Socio-economic factors play a substantial role in undergraduate medical education and could shape students reasoning and aspirations for pursuing research careers as physician-scientists. For some students outside the U.S., for instance, the motivation to participate in research was to boost their curriculum vitae (CVs) to allow for their career advancement and pursuing opportunities in developed countries [Citation53]. Similarly, students in developed countries who engage in research are often motivated by the goal of getting into a more competitive residency program. In other regions of the world, particularly in certain countries such as Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and Iran, cultural and religious contexts interplay with research during undergraduate medical education – this was quite a unique theme relevant to these settings. For instance, lack of mentors for female students was due to religious gender restrictions where male clinicians could not mentor female students [Citation1,Citation54,Citation55] in some circumstances.

Barriers – institutional, non-institutional

Despite the varied approaches and efforts at improving research during medical school, the literature amply provided instances of students expressing both institutional and non-institutional barriers to successful research participation. Prevalent institutional barriers included limited time, lack of access to electronic resources, lack of mentors, lack of supporting infrastructure, and prolongation of the process of acquiring equipment. Non-institutional barriers included lack of down time, inadequate scientific writing skills, and lack of self-efficacy. Many of the studies [Citation51,Citation56] that investigated factors working against student involvement in undergraduate research cited other key factors such as poor mentorship, lack of role models, and perceived lower salaries of academic physicians. Indeed, quality mentorship is strongly associated with a more positive research experience for students and may bolster interest in a research-oriented career [Citation51,Citation56].

While there exists a considerable overlap regarding contemporary perceptions of barriers toward research globally, students from developing countries face many more hurdles not only to their research participation but medical education in general. Examples include lack of funds [Citation57]), insufficient access to electronic resources [Citation58], constrained availability of the internet [Citation57,Citation59] and sometimes, even war/conflicts [Citation57].

Several limitations to this review should be noted. As mentioned earlier, our search excluded many U.S. articles by our inclusion criteria. Moreover, only studies written in English were included. There was also difficulty in functional comparisons as there were a variety in the details of the methods used in the studies and variations in medical education systems globally.

Conclusion and recommendation

This review examined the perspectives of medical students regarding research during medical education from a global perspective. Increasingly, research in medical education has been encouraged throughout the continuum of medical education. While these programs and efforts are laudable, they have not been without controversies. Outcomes have been mixed and the targets (medical students) were sometimes unaware of the opportunities available to them. Some medical students also engaged or participated in research for reasons other than for evidence-based practice or pursuit of physician-scientist career.

A consensus of medical students regarding the need and importance of research in undergraduate medical education exists in a global context. While the need and importance of research were upheld, barriers to it were passionately expressed. The perspective on the decline in the numbers of physician-scientists was that of a global accord. Differences in the thematic perspectives of research in medical education were quite minor and difficult to finely characterize.

Medical education systems vary greatly worldwide yet medical student perspectives on research in medical education revealed several common universal themes. Hence, a convergence of ideas amongst medical educators from different cultures could be possible to enhance research in undergraduate medical education. A global effort that harnesses an understanding of the concordances in the perspectives on the issues faced by medical students regarding research instruction and learning in medical schools could foster the training of physicians imbued with evidence-based practice and perhaps more inclined to become physician-scientists. Thus, a coordinated global response could promote and re-emphasize the importance of evidence-based medicine in clinical practice and potentially address the decline in the numbers of physician-scientists.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Jane Moran, Medical Librarian, and Ms. Sarah Wade, Assistant Medical Librarian, of the Campbell University School of Osteopathic Medicine for helping with the literature sourcing and search strategies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

C. Stone

C. Stone is a second year medical student. He has a BS in Biology from Mary Washington University.

G. Y. Dogbey

G. Y. Dogbey is a Biostatistician. He holds a Ph.D. in Mathematics Education with cognate specializations in Applied Statistics as well as in Research, Measurement, and Evaluation.

S. Klenzak

S. Klenzak, completed his medical school and psychiatry residency at UNC-Chapel Hill. He is the Program Director for the psychiatry residency at Cape Fear Valley Hospital in Fayetteville, NC and co-leads the ED Crisis Service and consult-liaison service.

K. Van Fossen

K. van Fossen, is the Co-Program Director for the General Surgery Residency Program at Cape Fear Valley Medical Center. She currently is the clerkship director for the general surgery medical student rotations.

B. Tan

B. Tan is a second year medical student. He holds a BS in Exercise Science with a minor in Military Science/Leadership from Appalachian State University.

G. D. Brannan

G. D. Brannan., is Associate Dean for Research. In her role, she provides expertise and oversight on research education and outcomes for the school and residency programs.

References

- Abu-Zaid A, Alkattan K. Integration of scientific research training into undergraduate medical education: a reminder call. Med Educ Online. 2013;18(1):22832.

- DeFranco DB, Sowa G. The importance of basic science and research training for the next generation of physicians and physician scientists. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28(12):1919–13.

- Bennett C. Why all medical students need to experience research? Aust Med Student J. 2016 Jun 4; [cited 2017 Nov 11]. Available from: http://www.amsj.org/archives/4796

- Mahmood Shah SM, Sohail M, Ahmad KM, et al. Grooming future physician-scientists: evaluating the impact of research motivations, practices, and perceived barriers towards the uptake of an academic career among medical students. Cureus. 2017;9(12):e1991.

- Furuya H, Brenner D, Rosser C. On the brink of extinction: the future of translational physician-scientists in the United States. J Transl Med. 2017;15:88.

- Yang VW. The future of physician-scientists–demise or opportunity? Gastroenterology. 2006;131(3):697–698.

- Jenicek M. The hard art of soft science: evidence-based medicine, reasoned medicine or both? J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12(4):410–419.

- Ghali WA, Saitz R, Eskew AH, et al. Successful teaching in evidence-based medicine. Med Educ. 2000;34(1):18–22.

- Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t: it’s about integrating individual clinical expertise and the best external evidence. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71–72.

- Wyngaarden JB. The clinical investigator as an endangered species. N Engl J Med. 1979;301(23):1254–1259.

- Gutierrez-Hartmann A. The vanishing physician-scientist? J Clin Invest. 2010;120(5):1367.

- Garrison HH, Deschamps AM. NIH research funding and early career physician scientists: continuing challenges in the 21st century. FASEB J. 2014;28(3):1049–1058.

- Siddaiah-Subramanya M, Singh H, Tiang KW. Research during medical school: is it particularly difficult in developing countries compared to developed countries? Adv Med Educ Pract. 2017;8:771–776.

- Abu-Zaid A, Alnajjar A. Female second-year undergraduate medical students’ attitudes towards research at the College of Medicine, Alfaisal University: a Saudi Arabian perspective. Perspect Med Educ. 2014;3(1):50–55.

- Al-Halabi B, Marwan Y, Hasan M, et al. Extracurricular research activities among senior medical students in Kuwait: experiences, attitudes, and barriers. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2014;5:95–101.

- Burgoyne LN, O’Flynn S, Boylan GB. Undergraduate medical research: the student perspective. Med Educ Online. 2010;15:5212.

- de Oliveira NA, Luz MR, Saraiva RM, et al. Student views of research training programmes in medical schools. Med Educ. 2011;45(7):748–755.

- Rosenkranz SK, Wang S, Hu W. Motivating medical students to do research: a mixed methods study using self-determination theory. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:95.

- Stockfelt M, Karlsson L, Finizia C. Research interest and activity among medical students in Gothenburg, Sweden, a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):226.

- Carter J, McClellan N, McFaul D, et al. Assessment of research interests of first-year osteopathic medical students. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2016;116(7):472–478.

- Charting-Outcomes-US-Allopathic-Seniors-2016.pdf. [cited 2017 Dec 31]. Available from: http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Charting-Outcomes-US-Allopathic-Seniors-2016.pdf

- Charting-Outcomes-IMGs-2016.pdf. [cited 2017 Dec 31]. Available from: http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Charting-Outcomes-IMGs-2016.pdf

- Charting-Outcomes-US-Osteopathic-2016.pdf. [cited 2017 Dec 31]. Available from: http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Charting-Outcomes-US-Osteopathic-2016.pdf

- Guillory VJ, Sharp G. Research at US colleges of osteopathic medicine: a decade of growth. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2003;103(4):176–181.

- Brannan GD. Growing research among osteopathic residents and medical students: a consortium-based research education continuum model. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2016;116(5):310–315.

- Clark BC, Blazyk J. Research in the osteopathic medical profession: roadmap to recovery. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2014;114(8):608–614.

- Moraes DW, Jotz M, Menegazzo WR, et al. Interest in research among medical students: challenges for the undergraduate education. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2016;62(7):652–658.

- Park SJ, McGhee CN, Sherwin T. Medical students’ attitudes towards research and a career in research: an Auckland, New Zealand study. N Z Med J. 2010;123(1323):34–42.

- Jimmy R, Palatty PL, D’Silva P, et al. Are medical students inclined to do research? J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(12):2892–2895.

- Nel D, Burman RJ, Hoffman R, et al. The attitudes of medical students to research. S Afr Med J. 2013;104(1):33–36.

- Pathipati AS, Taleghani N. Research in medical school: a survey evaluating why medical students take research years. Cureus. 2016;8(8):e741.

- Mina S, Mostafa S, Albarqawi HT, et al. Perceived influential factors toward participation in undergraduate research activities among medical students at Alfaisal University-College of Medicine: a Saudi Arabian perspective. Med Teach. 2016;38(Suppl 1):S31–36.

- Baig SA, Hasan SA, Ahmed SM, et al. Reasons behind the increase in research activities among medical students of Karachi, Pakistan, a low-income country. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2013;26(2):117–121.

- Meraj L, Gul N, Zubaidazain, et al. Perceptions and attitudes towards research amongst medical students at Shifa College of Medicine. J Pak Med Assoc. 2016;66(2):165–189.

- Park SJ, Liang MM, Sherwin TT, et al. Completing an intercalated research degree during medical undergraduate training: barriers, benefits and postgraduate career profiles. N Z Med J. 2010;123(1323):24–33.

- Fang D, Meyer RE. Effect of two Howard Hughes Medical Institute research training programs for medical students on the likelihood of pursuing research careers. Acad Med. 2003;78(12):1271–1280.

- Hunskaar S, Breivik J, Siebke M, et al. Evaluation of the medical student research programme in Norwegian medical schools. A survey of students and supervisors. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9:43.

- Dagher MM, Atieh JA, Soubra MK, et al. Medical Research Volunteer Program (MRVP): innovative program promoting undergraduate research in the medical field. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:160.

- Abdulghani HM, Shaik SA, Khamis N, et al. Research methodology workshops evaluation using the Kirkpatrick’s model: translating theory into practice. Med Teach. 2014;36(Suppl 1):S24–29.

- Kumar HNH, Jayaram S, Kumar GS, et al. Perception, practices towards research and predictors of research career among UG medical students from coastal south India: a cross-sectional study. Indian J Community Med. 2009;34(4):306–309.

- Cruser Des A, Brown SK, Ingram JR, et al. Learning outcomes from a biomedical research course for second year osteopathic medical students. Osteopath Med Prim Care. 2010;4:4.

- Steffen J, Grabbert M, Pander T, et al. Finding the right doctoral thesis - an innovative research fair for medical students. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2015;32(3):Doc29.

- Ahmad F, Zehra N, Omair A, et al. Students’ opinion regarding application of epidemiology, biostatistics and survey methodology courses in medical research. J Pak Med Assoc. 2009;59(5):307–310.

- Windish DM, Huot SJ, Green ML. Medicine residents’ understanding of the biostatistics and results in the medical literature. JAMA. 2007;298(9):1010–1022.

- Sumi E, Murayama T, Yokode M. A survey of attitudes toward clinical research among physicians at Kyoto University Hospital. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9:75.

- Mitwalli HA, Al Ghamdi KM, Moussa NA. Perceptions, attitudes, and practices towards research among resident physicians in training in Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2014;20(2):99–104.

- Ejaz K, Shamim MS, Shamim MS, et al. Involvement of medical students and fresh medical graduates of Karachi, Pakistan in research. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61(2):115–120.

- Funston G, Piper RJ, Connell C, et al. Medical student perceptions of research and research-orientated careers: an international questionnaire study. Med Teach. 2016;38(10):1041–1048.

- Oliveira CC, de Souza RC, Abe EHS, et al. Undergraduate research in medical education: a descriptive study of students’ views. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:51.

- O’Sullivan PS, Niehaus B, Lockspeiser TM, et al. Becoming an academic doctor: perceptions of scholarly careers. Med Educ. 2009;43(4):335–341.

- Siemens DR, Punnen S, Wong J, et al. A survey on the attitudes towards research in medical school. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:4.

- Tso SH. Facilitating medical students to undertake research. Med Teach. 2012;34(9):778.

- Peacock JG, Grande JP. A flexible, preclinical, medical school curriculum increases student academic productivity and the desire to conduct future research. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2015;43(5):384–390.

- Abu-Zaid A, Altinawi B. Perceived barriers to physician-scientist careers among female undergraduate medical students at the College of Medicine - Alfaisal University: a Saudi Arabian perspective. Med Teach. 2014;36(Suppl 1):S3–7.

- Kharraz R, Hamadah R, AlFawaz D, et al. Perceived barriers towards participation in undergraduate research activities among medical students at Alfaisal University-College of Medicine: a Saudi Arabian perspective. Med Teach. 2016;38(Suppl 1):S12–18.

- Amgad M, Man Kin TM, Liptrott SJ, et al. Medical student research: an integrated mixed-methods systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(6).

- Barnett-Vanes A, Hassounah S, Shawki M, et al. Impact of conflict on medical education: a cross-sectional survey of students and institutions in Iraq. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e010460.

- Anbari Z, Mohammadbeigi A, Jadidi R. Barriers and challenges in researches by Iranian students of medical universities. Perspect Clin Res. 2015;6(2):98–103.

- Sheikh AS, Sheikh SA, Kaleem A, et al. Factors contributing to lack of interest in research among medical students. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2013;4:237–243.