ABSTRACT

Effective mentoring enhances the personal and professional development of mentees and mentors, boosts the reputation of host organizations and improves patient outcomes. Much of this success hinges upon the mentor’s ability to nurture personalized mentoring relationships and mentoring environments, provide effective feedback and render timely, responsive, appropriate, and personalized support. However, mentors are often untrained raising concerns about the quality and oversight of mentoring support.

To promote effective and consistent use of mentor training in medical education, this scoping review asks what mentor training programs are available in undergraduate and postgraduate medicine and how they may inform the creation of an evidenced-based framework for mentor training.

Six reviewers adopted Arksey and O’Malley’s approach to scoping reviews to study prevailing mentor-training programs and guidelines in postgraduate education programs and in medical schools. The focus was on novice mentoring approaches. Six reviewers carried out independent searches with similar inclusion/exclusion criteria using PubMed, ERIC, EMBASE, SCOPUS, Google Scholar, and grey literature databases. Included were theses and book chapters published in English or had English translations published between 1 January 1990 and 31 December 2017. Braun and Clarke’s approach to thematic analysis was adopted to circumnavigate mentoring’s and mentor training’s evolving, context-specific, goal-sensitive, learner-, tutor- and relationally dependent nature that prevents simple comparisons of mentor training across different settings and mentee and mentor populations.

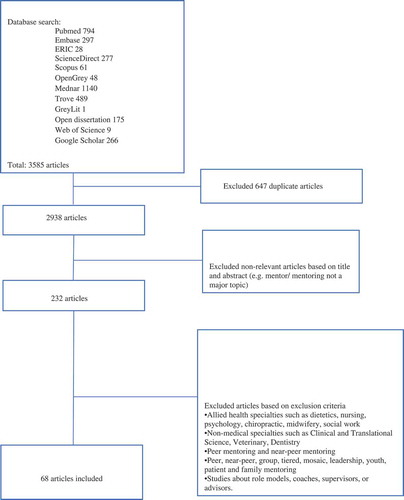

In total, 3585 abstracts were retrieved, 232 full-text articles were reviewed, 68 articles were included and four themes were identified including the structure, content, outcomes and evaluation of mentor training program.

The themes identified provide the basis for an evidence-based, practice-guided framework for a longitudinal mentor training program in medicine and identifies the essential topics to be covered in mentor training programs.

Introduction

Novice mentoring dominates the mentoring landscape in medical education [Citation1–Citation6] and has been found to enhance innovation and career progression [Citation7–Citation15], encourage research involvement amongst women and under-represented ethnic minorities, boost grant success [Citation16], and publications [Citation10,Citation17–Citation23] and navigating the complex landscape of academic life [Citation2,Citation24–Citation27]. Clinicians who have been mentored are also more motivated, resilient, have well-developed professional identities and feel better supported in their jobs than colleagues without mentors [Citation28–Citation31]. Mentoring also has a role in portfolio-learning [Citation32,Citation33] and competency-based curricula [Citation34–Citation38].

However, despite its success and expanded use in medical education, clinicians are poorly trained in the art of mentoring [Citation24,Citation34]. Feldman et al. (2009) reported that less than 15% of mentors received formal mentor training and Shea et al. (2011) noted that less than one-third of institutions have inclusion criteria for mentor recruitment [Citation17,Citation22]. Unsurprisingly mentors often fail to maximise mentoring opportunities [Citation24,Citation34]. Acknowledging this gap, Geraci and Thigpen (2017) emphasised the need for mentor training where mentors ‘engage in self-reflection and assessment to determine if in fact they have the attitudes, personal qualities, knowledge and skills and can regularly demonstrate the behaviours that are needed to maximize protégé success’ [Citation39]. Mentor training [Citation11,Citation40,Citation41] enhances the effectiveness of the mentoring process [Citation19,Citation23,Citation39,Citation42,Citation43], increases mentoring competency [Citation3,Citation4,Citation11,Citation44–Citation48], improves mentor satisfaction [Citation49], and boosts staff retention [Citation3,Citation4,Citation46,Citation50].

However, neither a clear syllabus nor an effective approach to mentor training exists [Citation1,Citation3–Citation6,Citation51]. These gaps are attributed to differences in the understanding, practice, goals and context of mentoring in medical education, unique curricula, diverse mentee and mentor populations, and distinctive healthcare and education systems [Citation1,Citation3–Citation6,Citation51]. Mistaken intermixing of peer, near-peer, group, mosaic, patient, family, youth, leadership, and novice mentoring which display distinct features, roles and approaches and their conflation with supervision, role modelling, coaching, advising, networking and/or sponsorship in many mentoring studies [Citation52,Citation53] calls into question prevailing understanding of mentoring practice and how it influences mentor training [Citation4,Citation46,Citation54–Citation67]. Concurrently, failure to circumnavigate the restrictions posed by mentorings’ evolving, adaptive, goal-specific, context-sensitive, and mentee-, mentor-, relationship-, and host organization-dependent nature (mentoring’s nature) that limits scrutiny of mentoring programs to those with similar healthcare, educational and clinical settings and congruous mentor and mentee populations has compounded the situation [Citation1,Citation3–Citation6,Citation51].

The lack of an ‘evidence based, user friendly mentor training curriculum’ [Citation23,Citation24,Citation41,Citation43,Citation68], the absence of clear guidelines on the design [Citation69–Citation71] and running of mentor training programs [Citation46,Citation61,Citation72–Citation75], reliance upon data from poorly constructed tools to appraise the training process, and limited support of the mentoring program [Citation46,Citation76–Citation78] also means that most mentor training programs have been carried out on an ad hoc basis creating variability in their quality, intensity, content, and effectiveness [Citation40,Citation43,Citation71,Citation79].

The need for this review

Growing concerns about lapses in professionalism and abuse of the mentoring process [Citation80–Citation86] have underlined the need to move mentor training from a ‘learned from examples, trial and error and peer observations’ approach to a more organized and regulated process [Citation40,Citation68,Citation87]. A scoping review of mentoring programs in medicine is necessary to explore the potential size and scope of available literature on mentor training in published peer-reviewed and prevailing grey literature [Citation88–Citation92].

With Johnson and Gandhi (2015) commenting that most senior mentors are not trained, the imperative to delineate core training elements and an effective approach to mentor training is evident. Adopting Levac et al.’s (2010) refinement of Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) framework for scoping reviews, we confine focus upon mentor training within a clearly defined mentoring approach that will better inform subsequent research projects [Citation88,Citation92,Citation93]. Focus upon novice mentoring which is defined as a ‘dynamic, context-dependent, goal-sensitive, mutually beneficial relationship between an experienced clinician and junior clinicians and/or undergraduates that is focused upon advancing the development of the mentee’[Citation6] also helps circumnavigate the limitations posed by mentoring’s nature [Citation1,Citation3–Citation6,Citation93,Citation94]. Similarities between novice mentoring practices in undergraduate and postgraduate programs and novice mentoring and research mentoring in medicine which is defined as ‘a dynamic, collaborative, reciprocal, and sustained relationship focused on an emerging researcher’s acquisition of the values and attitudes, knowledge, skills, and behaviours necessary to develop into a successful independent researcher’ allow them to be considered together [Citation1,Citation3–Citation6,Citation95]. The six steps proposed by Levac et al. (2010) are used to organise our methods and results [Citation90,Citation91,Citation93].

Stage 1: Identifying the research question

The six-member research team discussed the research question with medical librarians from the medical library at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine at the National University of Singapore (NUS), medical librarians at the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS) and local educational experts and clinicians at the NCCS, the Palliative Care Institute Liverpool, Duke-NUS Medical School and Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine. The research question the team decided upon was ‘What is known about mentor training programs in novice mentoring and what are the core elements of the mentor training program?’. All subspecialties of Surgery and Medicine as defined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education were included in this study given their common approaches to novice mentoring [Citation96]. Envisioning that the content of the scoping review will guide future research into mentor training, we also considered the comprehensiveness and feasibility of these tools given the longitudinal nature of the mentoring process and the mentor training program. This review adopted a PICOS format to study mentoring programs ()

Table 1. PICOs.

Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies

Guided by librarians at the NUS' medical library and the NCCS' medical library and by local educational experts and clinicians at the NCCS, the Palliative Care Institute Liverpool, Duke-NUS Medical School, and Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, the six members of the research team determined the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the review. The broad nature of the research question meant that pilot searches were carried out on variations of the word ‘mentor training’ or ‘frameworks’ that appeared in the title or abstract of articles in medicine. The six members of the research team reviewed the search terms and approved the inclusion/exclusion criteria in the abstract screening tool.

Guided by librarians at the NUS' medical library and the NCCS' medical library and by local educational experts and clinicians at the NCCS, the Palliative Care Institute Liverpool, Duke-NUS Medical School, and Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, the six members of the research team determined that Pubmed, Embase, ERIC, ScienceDirect, Scopus, Google scholar databases, and a grey literature databases including OpenGrey, Trove, Mednar, Web of Science, Open Dissertations, and British Education Index databases would be used [Refer to ].

Pilot searches were carried out on variations of the word ‘mentor’ and ‘training’ that appeared in the title or abstract of articles were performed using GreyLit and PubMed databases. Applying the abstract screening tool that the research team designed, the six members of the research team independently read through the abstracts of all the articles identified in the pilot and applied the inclusion/exclusion criteria in the abstract screening tool to the abstracts retrieved. Having discussed the individual results of their pilot searches online and at face-to-face reviewers’ meetings, the six members of the research team reviewed the search terms and employed Sambunjak et al.’s ‘negotiated consensual validation’ approach [Citation97] to achieve consensus on the inclusion/exclusion criteria for the search. The six members of the research team agreed that all research methodologies (quantitative and qualitative) written in English or had English translations would be included. Excluded from the review were articles that did not confine themselves to mentor training in medicine. The search was confined to years 1 January 2000–31 December 2017 as papers before the year 2000 often conflated mentoring with supervision, role modelling, coaching, advising, networking, and/or sponsorship [Citation1,Citation3–Citation6]. There was little change to the inclusion/exclusion criteria following the pilot searches.

The finalised search strategy included the keywords: ‘mentor training’, ‘mentorship training’, ‘mentoring competency’, ‘faculty development’ AND ‘medical faculty’ and their combinations and used in all databases. The same keywords were used for all the databases. All allied health specialities (e.g., dietetics, nursing, psychology, chiropractic, midwifery, social work) and non-medical professions (e.g., science, veterinary, dentistry) were excluded. Mentoring training in peer, near-peer, group, mosaic, patient, family, youth, leadership, mixed and e-mentoring, role modelling, coaching, supervision, networking, and/or advising were excluded.

Stage 3: Selecting studies to be included in the review

The five members of the team adopted similar search strategies to carry out independent searches for articles about mentoring training in novice mentoring involving the agreed upon databases. All searches were carried out between the 18 July 2018 and the 18 September 2018. Using inclusion and exclusion criteria of papers agreed upon by the research team, titles and abstracts of the papers were independently reviewed by each member of the research team. To ensure concordance and consistency in the search approach, each author examined approximately 50 titles and abstracts using the same search terms, database, and the abstract screening tool and compared their results in online discussions with all the team members. Once clarity on the search terms, inclusion, and exclusion criteria were established, the reviewers proceeded to carry out their independent searches of the agreed upon databases. For the first database being searched, each member of the review team worked on the same batch of 200 titles and abstracts and compared their findings at a weekly face-to-face meeting that were supplemented by online discussions in the event consensus could not be attained and the full-text had to be downloaded and discussed by all the team members. The six-member research team used Sambunjak et al.’s ‘negotiated consensual validation’ approach [Citation97] to achieve consensus on the final list of articles to be included in the scoping review [Refer to ].

All the articles from the final list of included articles were then downloaded and reviewed independently by each author for inclusion into the study. Each study team member then imported the titles meeting the inclusion criteria into EndNote, to remove duplicates, organise the references, and create their individual lists of abstracts to be studied. The individual lists were discussed at research team meetings where Sambunjak et al.’s (2010) approach of ‘negotiated consensual validation’ [Citation97] was used to reach consensus on a final list of abstracts to be studied.

Stage 4: Data characterisation and analysis

To carry out a comprehensive review of what is known of mentor training in novice mentoring requires comparing the findings of diverse studies. This process is complicated by mentoring’s nature which limits studies to mentoring programs in similar specialities, settings, healthcare and educational settings, and mentor and mentee populations. Similar obstacles have been faced with studies of mentoring approaches, the matching process that pairs mentees and mentors, Mentoring Relationships (MRs), and the mentoring culture. To circumnavigate these restrictions, studies of matching, MRs and mentoring culture have adopted Braun and Clarke’s approach to thematic analysis [Citation98] to identify consistencies across dissimilar settings, goals and mentee and mentor populations. Braun and Clarke’s approach to thematic analysis [Citation98] also circumnavigates a wide range of research methodologies present amongst the included articles which prevent the use of statistical pooling and analysis [Citation98–Citation100]. Thomas et al. (2014) also highlights that thematic analysis is necessary when studying socio-culturally influenced educational processes such as mentoring.

To evaluate the consistent elements within prevailing mentoring tools and discern the approaches that underpinned the design of these tools the five-members research team worked independently constructing ‘codes’ from the ‘surface’ meaning of the same 15 included articles. Thematic saturation was attained after nine articles. The coding process began with line-by-line coding, followed by focused coding ‘evolving to produce categories that responded to these codes [Citation101]. The authors discussed their analysis online and at the author’s meeting to agree upon a common coding framework and code book using Sambunjak et al.’s ‘negotiated consensual validation’ approach [Citation97]. Using the common coding framework and code book, the authors independently coded the articles from the ‘surface’ meaning of the data ‘across the entire data set’ and the ‘detail rich’ codes were grouped together to identify semantic themes [Citation98,Citation102]. The data was regularly reviewed to ensure all relevant excerpts were coded [Citation98,Citation103]. The themes, coding framework, and code book were also constantly reviewed as part of the iterative process employed within the study [Citation3,Citation98,Citation103]. The authors met face-to-face and online to discuss their themes and Sambunjak et al.’s ‘negotiated consensual validation’ approach [Citation97] was employed to achieve consensus on the final list of themes.

To highlight the wealth of data being reviewed, Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) descriptive-analytic method was employed [Citation88,Citation93,Citation104] to help contextualize the articles being reviewed and to help the coding process. The descriptive-analytic method records information about the ‘“process” of each programme or intervention included in the review so that its “outcome” is contextualized and more understandable to readers’ [Citation88]. To ensure consistency in this process and comparability with prevailing reviews, the authors adapted the data charting form used by Tan et al. (2018) to chart the characteristics of all 49 articles included in this scoping review which included author details, year of publication, purpose of the study/research question, practice setting, methodology, population characteristics, and outcome evaluation (variables of evaluation, evaluation responses, and effectiveness of implementation). ()

Stage 5: Collating, summarising, and reporting the results

In total, 4602 titles were reviewed, 3355 abstracts were scrutinised, 232 full-text articles were identified, and 68 articles were included in this scoping review. In keeping with Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and Levac et al.’s (2010) recommendations, this section will consider the ‘numerical and thematic analysis’ [Citation88,Citation93].

Themes

Thematic analysis revealed four themes: structure, content, outcomes, and evaluation of the mentor training program.

Structure of mentor-training program

All mentor training programs were designed and supported by a host organization [Citation105]. Abedin et al. (2013) found that of the 55 Academic Health Centres surveyed, 96% provided mentor training at a program level and 93% at an institutional level. The general goals of the programs were to train and support mentors [Citation2,Citation6–Citation11,Citation13,Citation15,Citation17,Citation30,Citation48–Citation51,Citation70,Citation77,Citation81,Citation82,Citation86,Citation95,Citation106,Citation107] and ensure a consistent mentoring experience for mentees [Citation108,Citation109]. McCulloch et al. (2015) and Rhodes (2013) found that mentor training programs also motivate mentors.

Design of mentor-training programs pivots on three domains. The first domain relates to the host organization and its goals, curriculum, mentoring approach, support of the program and its mentoring guidelines, professional standards, and codes of conduct. The second domain relates to the mentor and their availability, motivations, interests, competencies, abilities, experiences and sometimes competing for duties [Citation7,Citation9–Citation11,Citation15,Citation17,Citation30,Citation46,Citation50,Citation95,Citation106]. The third domain considers the trainees and their needs, motivations, goals, abilities, experiences, commitment, and desired characteristics of a mentor [Citation7,Citation9–Citation11,Citation15,Citation17,Citation23,Citation30,Citation50,Citation95,Citation106,Citation110]. Tillman et al. (2013) noted that to meet the mentees’ desire for mentors with experience, qualifications and academic standings, most programs recruited experienced clinicians-scientists [Citation1,Citation3–Citation6].

Design framework of the program

Libby et al. (2016) and Sood et al. (2016) suggested that the design of the mentoring program should be determined by individual competencies of the mentor and mentee and the intuitional factors, whilst Keyser et al. (2008) suggested considering mentor selection criteria, mentor incentives, mentor–mentee relationships and research and professional development.

Duration and frequency of mentor-training sessions

Mentor-training was carried out in ‘bursts’ of two to nine sessions per month [Citation11,Citation78,Citation109] or ‘stretched’ over six to nine months and/or over different phases of the mentoring program [Citation76,Citation77]. ‘Burst’ programs last about 2 h whilst ‘stretched’ programs tend to be between 6 h to two full days in duration [Citation73,Citation78,Citation105]. Various combinations of ‘burst’ and ‘stretched’ sessions have been proposed although the rationale for these designs was not specified [Citation11,Citation40,Citation41,Citation76]. Fornari et al. (2014) recommended that training begins at the start of the semester to help prepare mentors for their roles and responsibilities.

Modes of delivery

One-off orientation program

Most programs mandate attendance of orientation programs and most supplemented these programs with either web-based, face-to-face, and/or peer training [Citation109].

Lunchtime sessions

Lunchtime sessions focused on sharing personal experiences and ideas in small groups of four to five individuals [Citation77], interactive case-based discussions or seminars [Citation11,Citation77,Citation105,Citation108].

Role-plays

Role-plays were used to demonstrate mentoring skills [Citation105] and constructive peer feedback [Citation76].

Small group discussion

Consisting of 6–14 participants small group discussions focused on teaching approaches [Citation77], grant writing [Citation11] and fostering mentor relationships, independence and work–life balance [Citation40], challenges to communication, promoting mentoring of women and under-represented groups, reflections [Citation78], and problem-solving [Citation11,Citation105].

Didactic presentations or lectures

External experts were often employed to conduct lectures on cultural sensitivity [Citation77] and professional [Citation76,Citation105], educational,,,, and clinical mentoring [Citation76].

Seminars

Schmidt et al. (2010) ran six seminars on the required skills and roles of the mentor [Citation107] whilst Feldman et al. (2012) employed 10 case-based seminars over 5 months delivering skills-based exercises, case discussions and ‘key information relevant to all mentors’. The ‘Entering Mentoring' seminar discussed strategies, created a forum for discussions and provided an opportunity for reflection [Citation40,Citation41,Citation43].

Workshops

Workshops last a day or two and were more didactic [Citation40] and theoretical [Citation111], addressed practical issues [Citation73] or special interest topics [Citation73,Citation78,Citation105,Citation108,Citation111], updates to the program, interpersonal, communication, organizational, diversity training and knowledge and skills training, and guidance to new mentors [Citation11,Citation12,Citation17,Citation45,Citation110,Citation112].

Johnson and Gandhi (2015) reported improved mentoring competencies, self-efficacy scores and confidence in dealing with diversity following a 2-day workshop.

Forum

Open forums allowed mentors to discuss their experiences and review changes to the program [Citation32].

Mentoring for mentors

Having new mentors shadow and then mentored by senior mentors provides training and support for new mentors [Citation11,Citation113,Citation114]. Though pairing mentors to mentees was primarily mentee-initiated and based on research and career interests and/or skills [Citation113], Bland et al. (2015) reported that matching resulted in higher research activity while Shollen et al. (2014) found that mentee-initiated matching resulted in increased career satisfaction. A combined matching process has been proposed as a means of reducing mismatches and failed relationships [Citation115,Citation116]. Feldman et al. (2012) reported the use of an online platform to facilitate the creation of mentoring networks that provide mentees with specific, accessible and timely support [Citation117–Citation119].

Training content

The importance of appropriate training content is underlined by evidence that up to 15% of mentoring relationships failed as a result of mentors not understanding their obligations [Citation115]. Only three [Citation120] mentor training programs were ‘field tested’ [Citation11,Citation40]. The topics covered were determined by the program developers and the ‘general’ [Citation73,Citation74,Citation78,Citation109] and ‘specific’ needs of the mentors [Citation77].

Selection of ‘specific’ mentoring topics was informed by the particular needs, context, and goals of the mentoring program, the mentor’s experience and knowledge on the topic, the characteristics and needs of the mentee and the problems faced by mentees, mentors, and mentoring relationships within the program [Citation11,Citation77,Citation114]. In the clinical research setting, for example, mentors were trained to promote interdisciplinary research, research design, grant writing [Citation77], clinical research skills, and preparation of articles for publication [Citation95,Citation121].

The topics covered in general mentoring skill training include communication skills [Citation122], aligning expectations [Citation11,Citation78,Citation95,Citation109], establishing and overseeing compliance of codes of conduct, standards of practice, timelines and the roles and responsibilities of mentors and mentees [Citation71], assessing professional development [Citation114], and mentoring progress [Citation78,Citation95,Citation109]. Additional topics include promoting professional development, handling difficult scenarios, challenging mentees effectively, nurturing mentoring relationships [Citation12], addressing diversity-related issues [Citation45,Citation123], fostering independence [Citation40,Citation46,Citation73,Citation77,Citation78,Citation97,Citation105,Citation111], role modelling, networking, career advising and guidance on publications, promotions, departmental politics and addressing psychosocial issues [Citation114,Citation119]. Pfund et al. (2014) adapted the Entering Mentoring [Citation124] program that focuses on maintaining effective communication, aligning expectations, assessing understanding and diversity, fostering independence and professional development and articulating a mentoring philosophy and plan [Citation16] to the clinical research setting and found an improvement in competencies in all domains.

General teaching skills training include how to deliver curriculum content, use of educational tools and new approaches [Citation78], demonstration of practical skills through role-play and case discussions [Citation77,Citation78,Citation105], debriefing and providing and receiving feedback [Citation46,Citation77,Citation111]. Other topics also include interpersonal, motivational, coaching, research, self-efficacy, networking, ethics, disciplinary, teaching and technical skills training [Citation95], active listening, building relationships, career guidance, and cultural sensitivity [Citation16,Citation27,Citation95,Citation112].

Augmenting the mentor training program

Many programs augment mentor training programs with the peer, near-peer, online [Citation120], ‘functional’ (skills based or project-based mentoring) [Citation29,Citation113], mentoring committees and mentoring networks. Mentor consultation services and mentoring committees [Citation11] provide mentees with the additional mentor and peer mentor support whilst mentoring networks [Citation29] provide a mix of peer and faculty support. Online services [Citation122,Citation125] provide mentors and mentees with supplemental resources including information on best mentoring practices and links to resources, such as mentoring agreements and individual development plans.

Peer support network

A support framework for mentors during the training such as the Peer-Onsite-Distance model helps mentors network and support one another [Citation46].

Impact of mentor-training programs

Mentor training boosts confidence in aligning expectations, working with diverse mentee groups and nurturing mentoring relationships [Citation77,Citation78,Citation105], improved communication skills, providing negative feedback, and addressing ‘difficult conversations’ [Citation12,Citation76–Citation78,Citation105,Citation123]. Tsen et al. (2012) found that mentors reported a renewed sense of enthusiasm after the mentor training program [Citation77].

Long-term benefits [Citation11,Citation30,Citation40,Citation113] include increased effectiveness, improved mentoring skills, academic productivity, increased promotions, awards and grants awarded [Citation108,Citation123].

Obstacles to mentor-training programs

The main obstacles to mentor training programs are a shortage of trained mentors, a lack of appreciation of mentor training and a lack of time, funding and accountability in designing and coordinating the mentor-training program [Citation27,Citation30,Citation115,Citation121,Citation122,Citation126]. The role of the host organization in supporting these programs also remain poorly elucidated [Citation27,Citation115,Citation122,Citation127].

Evaluating mentor-training programs

Investment in time and resources demand evaluation of mentor training programs. Yet many prevailing assessment tools are limited to pre- and post-assessments and self-rated tools [Citation45,Citation74,Citation76]. Anderson, Silet and Fleming’s (2012) apprised mentee empowerment and training, peer learning and mentor training, aligning expectations, mentee program advocate, mentor self-reflection, and mentee evaluation of mentor whilst Johnson et al. (2010) evaluated the sustainability of the program as long-term measures of the success of a mentor training program.

Surveys

Anonymized mentor surveys have been used to identify the most and least effective parts of the training program, changes in the participants’ views over the course of the program, and suggested improvements for future training sessions [Citation77,Citation78]. Surveys also assess participants’ satisfaction, the abilities of the facilitator or presenter [Citation105,Citation108], the relevance of the teaching material and extent to which the training objectives were met [Citation76–Citation78].

Surveys 6 months after the program [Citation77,Citation108] or at the latter part of a 6-month-long training program [Citation76] are used to capture changes to the mentor’s life and work [Citation76], mentor competency, and mentoring effectiveness [Citation108].

Program assessment tools

Keyser et al.s’ (2008) ‘Self-Assessment Tool for Documenting/Monitoring Institutional Roles in Supporting Research Mentorship’ attempts holistic and longitudinal appraisal of the mentoring program.

The Mentoring Competency Assessment measures changes [Citation12,Citation41,Citation122,Citation125] in communication, aligning expectations, assessing understanding, addressing diversity, and fostering independence [Citation69,Citation125].

The Mentorship Knowledge Test assesses content-specific knowledge [Citation103] whilst Lau et al. (2016) compared baseline and post-workshop mentorship competencies.

Stage 6: Undertaking consultations with key stakeholders

Stakeholders were consulted on the findings of this scoping review. To highlight the strength of the data to garner and to underline the critical nature of the findings, a quality appraisal of the articles was carried out using the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI) and the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) (). Whilst scoping reviews are not traditionally associated with quality assessments, the pool of papers identified in the searches were deemed sufficiently robust to undergo quality assessments. To contextualise the findings, the stakeholders were presented with the table created as part of Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) descriptive-analytic method [Citation88].

This contextualised and quality appraised data enhanced discussions with stakeholders and garnered their views on the relative importance of a mentor training program, the cost-effectiveness and viability of implementing the findings and also aided input into focus for future studies.

Discussion

This scoping review highlights the increasing importance placed upon mentor training [Citation95] in novice mentoring [Citation7–Citation11,Citation15]. However, despite evidence that mentor training improves knowledge, skills and attitudes and the need to support mentors in diverse settings [Citation7,Citation9–Citation11,Citation15,Citation17,Citation27,Citation30,Citation50,Citation95,Citation106,Citation121] to meet the changing needs of their mentees [Citation7,Citation9,Citation10,Citation15,Citation17,Citation30,Citation50,Citation106], adoption of mentor training programs has not been uniform particularly in clinical medicine, and informal mentoring programs. This scoping review also sketches the range of available mentor training programs and their content and approaches, the domains being evaluated and the key obstacles to effective mentor training. In so doing, this scoping review highlights the variability in the construct, content and focus of mentor training programs which inevitably impacts practice and oversight of mentoring programs, relationships, and processes [Citation128].

Whilst it was our intention to appreciate the scope of available literature and tools on mentor training in novice mentoring, it is evident that this mere sketch albeit an expansive one lacks depth [Citation128]. This limitation is largely the result of incomplete reporting of prevailing mentor training approaches, the contents of these programs, the manner that the training and the trainees are evaluated and how the program is able to provide effective support for mentors in training. Further limitations to this review lie in this scoping reviews’ adoption of a pragmatic approach that balances practicality and available resources and focuses upon publications in English and those that had English translations. A further limitation to the generalizability of the findings of this scoping review is the presence of a small pool of papers included in this scoping review and the preponderance of American and European papers that limit their global impact. Reliance upon self-rated scales [Citation41] and tools still rooted in ‘Cartesian reductionism and Newtonian principles of linearity’ [Citation129] that fail to consider the evolving nature of the mentoring process [Citation1,Citation3–Citation6] also underline the need for a systematic reviews.

However, despite these limitations, this scoping review was carried out with the required rigour and transparency advocated by Arksey and O’Malley (2002), Levac et al. (2009, 2010) and Pham et al. (2014). Use of Endnote a bibliographic manager ensured all the citations from the various databases were properly accounted for.

We believe the findings of this scoping review will be of interest to educators and program designers in undergraduate and postgraduate settings and will help inform the design of future mentor training programs.

The lack of consensus and gaps in evidence on the best approach, necessary content, quality assessment of the programs and evaluation of the competence of mentors following training, also underscore the need for a systematic review of mentor training in medicine.

Directions for future research

Actualising a consistent mentor training program depends on evaluations of the mentoring process. To facilitate this goal, a critical area for future study must be a design of effective tools to assess mentoring competencies and efficacy longitudinally and holistically. It is only thus, can mentoring in medical education develop to its full potential.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ms Annelissa Chin, Senior Librarian from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, for her guidance and advice on the literature search strategies for this paper. The authors would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers whose guidance and feedback greatly enhanced this manuscript

This paper is dedicated to the late Dr S. Radha Krishna, whose advice and insights were critical to the conceptualization of this review.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ikbal M, Wu J, Wahab MT, et al. Mentoring in palliative medicine: Guiding program design through thematic analysis of mentoring in internal medicine between 2000 and 2015. J Palliat Care Med. 2017;7:318.

- Jackson VA, Palepu A, Szalacha L, et al. “Having the right chemistry”: a qualitative study of mentoring in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78(3):328–16.

- Sng JH, Pei Y, Toh YP, et al. Mentoring relationships between senior physicians and junior doctors and/or medical students: a thematic review. Med Teach. 2017;39(8):866–875.

- Tan YS, Teo SWA, Pei Y, et al. A framework for mentoring of medical students: thematic analysis of mentoring programmes between 2000 and 2015. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2018;23(4):671–697.

- Toh Y, Lam B, Soo J, et al. Developing palliative care physicians through mentoring relationships. Palliat Med Care. 2017;4:1–6.

- Wahab M, Ikbal M, Wu J, et al. Toward an interprofessional mentoring program in palliative care—a review of undergraduate and postgraduate mentoring in medicine, nursing, surgery and social work. J Palliat Care Med. 2016;6:292.

- Anderson L, Silet K, Fleming M. Evaluating and giving feedback to mentors: new evidence-based approaches. Clin Transl Sci. 2012;5(1):71–77.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215.

- Burnham EL, Schiro S, Fleming M. Mentoring K scholars: strategies to support research mentors. Clin Transl Sci. 2011;4(3):199–203.

- Cho CS, Ramanan RA, Feldman MD. Defining the ideal qualities of mentorship: a qualitative analysis of the characteristics of outstanding mentors. Am J Med. 2011;124(5):453–458.

- Feldman MD, Steinauer JE, Khalili M, et al. A mentor development program for clinical translational science faculty leads to sustained, improved confidence in mentoring skills. Clin Transl Sci. 2012;5(4):362–367.

- Johnson MO, Gandhi M. A mentor training program improves mentoring competency for researchers working with early-career investigators from underrepresented backgrounds. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2015;20(3):683–689.

- Kirsch JD, Duran A, Kaizer AM, et al. Career-focused mentoring for early-career clinician educators in academic general internal medicine. Am J Med. 2018;131(11):1387–1394.

- McGee R. Biomedical workforce diversity: the context for mentoring to develop talents and foster success within the ‘Pipeline’. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(Suppl 2):231–237.

- Meagher E, Taylor L, Probsfield J, et al. Evaluating research mentors working in the area of clinical translational science: a review of the literature. Clin Transl Sci. 2011;4(5):353–358.

- Pfund C, Byars-Winston A, Branchaw J, et al. Defining Attributes and Metrics of Effective Research Mentoring Relationships. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(Suppl 2):238–248.

- Feldman MD, Arean PA, Marshall SJ, et al. Does mentoring matter: results from a survey of faculty mentees at a large health sciences university. Med Educ Online. 2010;23:15.

- Garman KA, Wingard DL, Reznik V. Development of junior faculty’s self-efficacy: outcomes of a National Center of Leadership in Academic Medicine. Acad Med. 2001;76(10 Suppl):S74–6.

- Palepu A, Friedman RH, Barnett RC, et al. Junior faculty members’ mentoring relationships and their professional development in U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 1998;73(3):318–323.

- Ramanan RA, Phillips RS, Davis RB, et al. Mentoring in medicine: keys to satisfaction. Am J Med. 2002;112(4):336–341.

- Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. Jama. 2006;296(9):1103–1115.

- Shea JA, Stern DT, Klotman PE, et al. Career development of physician scientists: a survey of leaders in academic medicine. Am J Med. 2011;124(8):779–787.

- Steiner JF, Curtis P, Lanphear BP, et al. Assessing the role of influential mentors in the research development of primary care fellows. Acad Med. 2004;79(9):865–872.

- Blanchard RD, Visintainer PF, La Rochelle J. Cultivating Medical Education Research Mentorship as a Pathway Towards High Quality Medical Education Research. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(9):1359–1362.

- Brown RT, Daly BP, Leong FTL. Mentoring in research: a developmental approach. Prof Psychol. 2009;40(3):306–313.

- Crites GE, Gaines JK, Cottrell S, et al. Medical education scholarship: an introductory guide: AMEE Guide No. 89. Med Teach. 2014;36(8):657–674.

- Sakushima K, Mishina H, Fukuhara S, et al. Mentoring the next generation of physician-scientists in Japan: a cross-sectional survey of mentees in six academic medical centers. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:54.

- Caruso TJ, Steinberg DH, Piro N, et al. A strategic approach to implementation of medical mentorship programs. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(1):68–73.

- Hernandez PR, Bloodhart B, Barnes RT, et al. Promoting professional identity, motivation, and persistence: benefits of an informal mentoring program for female undergraduate students. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0187531.

- Johnson MO, Subak LL, Brown JS, et al. An innovative program to train health sciences researchers to be effective clinical and translational research mentors. Acad Med. 2010;85(3):484–489.

- Pololi L, Knight S. Mentoring faculty in academic medicine. A new paradigm? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):866–870.

- Donato AA, George DL. A blueprint for implementation of a structured portfolio in an internal medicine residency. Acad Med. 2012;87(2):185–191.

- Holmboe ES, Ward DS, Reznick RK, et al. Faculty development in assessment: the missing link in competency-based medical education. Acad Med. 2011;86(4):460–467.

- Smesny AL, Williams JS, Brazeau GA, et al. Barriers to scholarship in dentistry, medicine, nursing, and pharmacy practice faculty. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(5):91.

- Carraccio C, Wolfsthal SD, Englander R, et al. Shifting paradigms: from Flexner to competencies. Acad Med. 2002;77(5):361–367.

- Mansvelder-Longayroux D, Beijaard DD, Verloop N. The portfolio as a tool for stimulating reflection by student teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2007;23:47–62.

- Dekker H, Driessen E, Ter Braak E, et al. Mentoring portfolio use in undergraduate and postgraduate medical education. Med Teach. 2009;31(10):903–909.

- Driessen E, van Tartwijk J, van der Vleuten C, et al. Portfolios in medical education: why do they meet with mixed success? A systematic review. Med Educ. 2007;41(12):1224–1233.

- Geraci SA, Thigpen SC. A review of mentoring in academic medicine. Am J Med Sci. 2017;353(2):151–157.

- Pfund C, House S, Spencer K, et al. A research mentor training curriculum for clinical and translational researchers. Clin Transl Sci. 2013;6(1):26–33.

- Pfund C, House SC, Asquith P, et al. Training mentors of clinical and translational research scholars: a randomized controlled trial. Acad Med. 2014;89(5):774–782.

- Ng E, Wang X, Keow J, et al. Fostering mentorship for clinician-investigator trainees: overview and recommendations. Clin Invest Med. 2015;38(1):E1–e10.

- Pfund C, Maidl Pribbenow C, Branchaw J, et al. Professional skills. The merits of training mentors. Science. 2006;311(5760):473–474.

- Blixen CE, Papp KK, Hull AL, et al. Developing a mentorship program for clinical researchers. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2007;27(2):86–93.

- Gandhi M, Johnson M. Creating More Effective Mentors: mentoring the Mentor. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(Suppl 2):294–303.

- Lewellen-Williams C, Johnson VA, Deloney LA, et al. The POD: a new model for mentoring underrepresented minority faculty. Acad Med. 2006;81(3):275–279.

- Moskowitz J, Thompson JN. Enhancing the clinical research pipeline: training approaches for a new century. Acad Med. 2001;76(4):307–315.

- Straus SE, Straus C, Tzanetos K. Career choice in academic medicine: systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(12):1222–1229.

- Wasserstein AG, Quistberg DA, Shea JA. Mentoring at the University of Pennsylvania: results of a faculty survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2):210–214.

- Kupfer DJ, Hyman SE, Schatzberg AF, et al. Recruiting and retaining future generations of physician scientists in mental health. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(7):657–660.

- Wesley L, Bin Mohamad Ikbal MF, Jingting W, et al. Towards a practice guided evidence based theory of mentoring in palliative care. J Palliat Care Med. 2017;7(296):2.

- Bhagia J, Tinsley JA. The mentoring partnership. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75(5):535–537.

- Levy BD, Katz JT, Wolf MA, et al. An initiative in mentoring to promote residents’ and faculty members’ careers. Acad Med. 2004;79(9):845–850.

- Alleyne SD, Horner MS, Walter G, et al. Mentors’ perspectives on group mentorship: a descriptive study of two programs in child and adolescent psychiatry. Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33(5):377–382.

- Andre C, Deerin J, Leykum L. Students helping students: vertical peer mentoring to enhance the medical school experience. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):176.

- Buddeberg-Fischer B, Vetsch E, Mattanza G. Career support in medicine - experiences with a mentoring program for junior physicians at a university hospital. Psychosoc Med. 2004;1:Doc04.

- Bussey-Jones J, Bernstein L, Higgins S, et al. Repaving the road to academic success: the IMeRGE approach to peer mentoring. Acad Med. 2006;81(7):674–679.

- Chen MM, Sandborg CI, Hudgins L, et al. A multifaceted mentoring program for junior faculty in academic pediatrics. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28(3):320–328.

- Files JA, Blair JE, Mayer AP, et al. Facilitated peer mentorship: a pilot program for academic advancement of female medical faculty. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(6):1009–1015.

- Fleming GM, Simmons JH, Xu M, et al. A facilitated peer mentoring program for junior faculty to promote professional development and peer networking. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):819–826.

- Kashiwagi DT, Varkey P, Cook DA. Mentoring programs for physicians in academic medicine: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88(7):1029–1037.

- Kman NE, Bernard AW, Khandelwal S, et al. A tiered mentorship program improves number of students with an identified mentor. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(4):319–325.

- Lord JA, Mourtzanos E, McLaren K, et al. A peer mentoring group for junior clinician educators: four years’ experience. Acad Med. 2012;87(3):378–383.

- Pololi LH, Evans AT. Group peer mentoring: an answer to the faculty mentoring problem? A successful program at a large academic department of medicine. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2015;35(3):192–200.

- Pololi LH, Knight SM, Dennis K, et al. Helping medical school faculty realize their dreams: an innovative, collaborative mentoring program. Acad Med. 2002;77(5):377–384.

- Singh S, Singh N, Dhaliwal U. Near-peer mentoring to complement faculty mentoring of first-year medical students in India. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2014;11:12.

- Welch JL, Jimenez HL, Walthall J, et al. The women in emergency medicine mentoring program: an innovative approach to mentoring. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(3):362–366.

- Silet KA, Asquith P, Fleming MF. Survey of mentoring programs for KL2 scholars. Clin Transl Sci. 2010;3(6):299–304.

- Fleming M, House S, Hanson VS, et al. The mentoring competency assessment: validation of a new instrument to evaluate skills of research mentors. Acad Med. 2013;88(7):1002–1008.

- Huskins WC, Silet K, Weber-Main AM, et al. Identifying and aligning expectations in a mentoring relationship. Clin Transl Sci. 2011;4(6):439–447.

- Straus SE, Johnson MO, Marquez C, et al. Characteristics of successful and failed mentoring relationships: a qualitative study across two academic health centers. Acad Med. 2013;88(1):82–89.

- Bradner M, Crossman SH, Vanderbilt AA, et al. Career advising in family medicine: a theoretical framework for structuring the medical student/faculty advisor interview. Med Educ Online. 2013;18(1):21173.

- Coyne K, Maw R, Rooney G, et al. Mentoring in genitourinary medicine. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17(12):795–798.

- Kirresh A, Patel VM, Warren OJ, et al. A framework to establish a mentoring programme in surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396(6):811–817.

- Lin SY, Laeeq K, Malik A, et al. Otolaryngology training programs: resident and faculty perception of the mentorship experience. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(8):1876–1883.

- Connor M, Bynoe AG, Redfern N, et al. Developing senior doctors as mentors: a form of continuing professional development. Report Of an initiative to develop a network of senior doctors as mentors: 1994–99. Med Educ. 2000;34(9):747–753.

- Tsen LC, Borus JF, Nadelson CC, et al. The development, implementation, and assessment of an innovative faculty mentoring leadership program. Acad Med. 2012;87(12):1757–1761.

- Varma JR, Prabhakaran A, Singh S, et al. Experience of a faculty development workshop in mentoring at an Indian medical college. Natl Med J India. 2016;29(5):286.

- Stamm M, Buddeberg-Fischer B. The impact of mentoring during postgraduate training on doctors’ career success. Med Educ. 2011;45(5):488–496.

- Byerley JS. Mentoring in the Era of #MeToo. Jama. 2018;319(12):1199–1200.

- Chopra V, Edelson DP, Saint S. A piece of my mind. Mentorship malpractice. Jama. 2016;315(14):1453–1454.

- Duck S, Stratagems, spoils, and a serpent’s tooth: on the delights and dilemmas of personal relationships. The dark side of interpersonal communication, 1994. p. 3–24.

- Long J. The dark side of mentoring. Aust Educ Res. 1997;24(2):115–133.

- Singh TSS, Singh A. Abusive culture in medical education: Mentors must mend their ways. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2018;34(2):145–147.

- Soklaridis S, Zahn C, Kuper A, et al. Men’s Fear of Mentoring in the #MeToo Era - What’s at Stake for Academic Medicine? N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2270–2274.

- Walensky RP, Kim Y, Chang Y, et al. The impact of active mentorship: results from a survey of faculty in the Department of Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):108.

- Pfund C, Spencer KC, Asquith P, et al. Building national capacity for research mentor training: an evidence-based approach to training the trainers. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2015;14(2):14: ar24.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

- Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108.

- Lorenzetti DL, Powelson SE. A scoping review of mentoring programs for academic librarians. J Acad Librarianship. 2015;41(2):186–196.

- Mays N, Roberts E. Synthesising research evidence. Studying the organisation and delivery of health services: research methods. N. Fullop, P. Allen, A. Clarke and N. Black. London: Routledge; 2001.

- Thomas A, Menon A, Boruff J, et al. Applications of social constructivist learning theories in knowledge translation for healthcare professionals: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2014;9:54.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69.

- Qiao Ting Low C, Toh YL, Teo SWA, et al. A narrative review of mentoring programmes in general practice. Educ Primary Care. 2018;29(5):259–267.

- Abedin Z, Biskup E, Silet K, et al. Deriving competencies for mentors of clinical and translational scholars. Clin Transl Sci. 2012;5(3):273–280.

- Wahab M, Wu JT, Ikbal MF, et al. Creating effective interprofessional mentoring relationships in palliative care- lessons from medicine, nursing, surgery and social work. Palliat Care Med. 2016;6:290.

- Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):72–78.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Haig A, Dozier M. BEME Guide no 3: systematic searching for evidence in medical education–Part 1: sources of information. Med Teach. 2003;25(4):352–363.

- Gordon M, Gibbs T. STORIES statement: publication standards for healthcare education evidence synthesis. BMC Med. 2014;12:143.

- Lingard L, Vanstone M, Durrant M, et al. Conflicting messages: examining the dynamics of leadership on interprofessional teams. Acad Med. 2012;87(12):1762–1767.

- Voloch K-A, Judd N, Sakamoto K. An innovative mentoring program for Imi Ho’ola Post-Baccalaureate students at the University of Hawai’i John A. Burns school of medicine. Hawaii Med J. 2007;66(4):102.

- Stenfors-Hayes T, Kalén S, Hult H, et al. Being a mentor for undergraduate medical students enhances personal and professional development. Med Teach. 2010;32(2):148–153.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288.

- Lau C, Ford J, Van Lieshout RJ, et al. Developing mentoring competency: does a one session training workshop have impact? Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(3):429–433.

- Feldman MD, Huang L, Guglielmo BJ, et al. Training the next generation of research mentors: the university of California, San Francisco, clinical & translational science institute mentor development program. Clin Transl Sci. 2009;2(3):216–221.

- Fornari A, Murray TS, Menzin AW, et al. Mentoring program design and implementation in new medical schools. Med Educ Online. 2014;19(1):24570.

- de Dios MA, Kuo C, Hernandez L, et al. The development of a diversity mentoring program for faculty and trainees: a program at the brown clinical psychology training consortium. Behav Ther (N Y N Y). 2013;36(5):121.

- Phitayakorn R, Petrusa E, Hodin RA. Development and initial results of a mandatory department of surgery faculty mentoring pilot program. J Surg Res. 2016;205(1):234–237.

- Santoro N, McGinn AP, Cohen HW, et al. In it for the long-term: defining the mentor-protege relationship in a clinical research training program. Acad Med. 2010;85(6):1067–1072.

- Freeman R. Towards effective mentoring in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1997;47(420):457–460.

- Gandhi M, Fernandez A, Stoff DM, et al. Development and implementation of a workshop to enhance the effectiveness of mentors working with diverse mentees in HIV research. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014;30(8):730–737.

- Welch J, Sawtelle S, Cheng D, et al. Faculty mentoring practices in academic emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(3):362–370.

- Yin HL, Gabrilove J, Jackson R, et al. Sustaining the clinical and translational research workforce: training and empowering the next generation of investigators. Acad Med. 2015;90(7):861–865.

- Ehrich LC, Hansford B, Tennent L. Formal mentoring programs in education and other professions: a review of the literature. Educ Administration Q. 2004;40(4):518–540.

- Schafer M, Pander T, Pinilla S, et al. A prospective, randomised trial of different matching procedures for structured mentoring programmes in medical education. Med Teach. 2016;38(9):921–929.

- DeCastro R, Sambuco D, Ubel PA, et al. Mentor networks in academic medicine: moving beyond a dyadic conception of mentoring for junior faculty researchers. Acad Med. 2013;88(4):488–496.

- Libby AM, Hosokawa PW, Fairclough DL, et al. Grant Success for early-career faculty in patient-oriented research: difference-in-differences evaluation of an interdisciplinary mentored research training program. Acad Med. 2016;91(12):1666–1675.

- Shollen SL, Bland CJ, Center BA, et al. Relating mentor type and mentoring behaviors to academic medicine faculty satisfaction and productivity at one medical school. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1267–1275.

- Sorkness CA, Pfund C, Ofili EO, et al. A new approach to mentoring for research careers: the National Research Mentoring Network. BMC Proc. 2017;11(12):22.

- Abedin Z, Rebello TJ, Richards BF, et al. Mentor training within academic health centers with clinical and translational science awards. Clin Transl Sci. 2013;6(5):376–380.

- Sood A, Tigges B, Helitzer D. Mentoring early-career faculty researchers is important-but first “Train the Trainer”. Acad Med. 2016;91(12):1598–1600.

- Walters KL, Simoni JM, Evans-Campbell TT, et al. Mentoring the mentors of underrepresented racial/ethnic minorities who are conducting HIV research: beyond cultural competency. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(Suppl 2):288–293.

- Handelsman J, Handelsman H. Entering mentoring: a seminar to train a new generation of scientists. Wisconsin, USA: UW Press; 2005.

- Sorkness CA, Pfund C, Asquith P, et al. Research mentor training: initiatives of the university of wisconsin institute for clinical and translational research. Clin Transl Sci. 2013;6(4):256–258.

- Straus SE, Chatur F, Taylor M. Issues in the mentor–mentee relationship in academic medicine: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2009;84(1):135–139.

- Wong BM, Goldman J, Goguen JM, et al. Faculty-resident “Co-learning”: a longitudinal exploration of an innovative model for faculty development in quality improvement. Acad Med. 2017;92(8):1151–1159.

- Tricco A, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16(1):15.

- Mennin S. Self-organisation, integration and curriculum in the complex world of medical education. Med Educ. 2010;44(1):20–30.

Appendix

Table A1. Summary of Papers with MERSQI and COREQ Scoring.