ABSTRACT

Background: There is a strong need to include training of research methods in training programs for physicians. International clinical research training programs (CRTP) that comprehensively introduce the methodology of clinical research and combined with practice should be a priority. However, few studies have reported a multimodal international CRTP that provides clinicians with an introduction to the quantitative and methodological principles of clinical research.

Objective: This manuscript is intended to comprehensively describe the development process and the structure of this multimodal training program.

Methods: The CRTP was comprised of three distinct, sequential learning components: part 1 – a six-week online eLearning self-study; part 2 – a series of three weekly interactive synchronous webinars conducted between Durham, North Carolina, USA and Beijing, China; and part 3 – a five-day in-person workshop held at Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University (BFH-CMU). Self-assessment quiz scores and participation rates were used to evaluate effectiveness of the training program. Participants’ demographic characteristics, research experience, satisfaction and feedback on the program were collected using questionnaires.

Results: A total of 50 participants joined the CRTP. Forty-four participants (88%) completed the program satisfaction questionnaires. The average quiz score of the six eLearning units varied from 31% to 73%. Among the three components of the program, the online eLearning self-study was felt to be the most challenging. Thirty-nine (89%) of the surveyed respondents were satisfied with all components of the training program. Among the respondents, 43 (98%) felt the training was helpful in preparing them for future clinical research projects and expressed willingness to recommend the program to other colleagues.

Conclusions: We established a multimodal international collaborative training program. The program demonstrated acceptable participation rates and high satisfaction among Chinese clinicians. It provides a model that may be used by others developing similar international clinical research training programs for physicians.

Introduction

With the increasing societal concern for population health, the education and training of clinical and translational researchers has been an important priority [Citation1]. Reliable medical results are generated from high-quality studies with the understanding of epidemiology and biostatistics. Recently, there has been a growing desire among young clinicians for clinical research training, especially training in research methods [Citation2,Citation3]. Domestically within China, continuing education programs on clinical research are provided by the Chinese Medical Association and taught by Chinese professors [Citation4]. Also, there is an International Research Camp for Clinical Research Design and Program Development (IRCCRDPD) program hosted by Peking University Clinical Research Institute [Citation5]. These programs offer short-term training (usually less than one week) and primarily invite overseas professors to attend and give courses or lectures. Fogarty International Clinical Research Scholars and Fellows Program and Harvard Medical School’s Introduction to Clinical Research Training (ICRT)–Japan program are two well-known international training programs [Citation1,Citation6,Citation7], however, they are not appropriate for Chinese clinicians or not available in China.

Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University (BFH-CMU), is a tertiary hospital with a long history of graduate, collaborative training programs in partnership with many universities, hospitals, and institutes. BFH-CMU decided to conduct a high-level training program to improve the quality of clinical research skills among young and middle-aged Chinese physicians. Therefore, BFH-CMU and Duke University School of Medicine jointly organized a clinical research training certificate program (BFH-Duke CRTP), which provides rigorous training in the quantitative and methodological principles of clinical research.

This article aims to comprehensively describe the development process and the structure of the multimodal training program.

Materials and methods

The organizations of BFH-Duke CRTP

Beijing friendship hospital, capital medical university

BFH-CMU established in 1952, is a large-scale general hospital in Beijing. With strengths in multiple clinical areas, BFH-CMU is the home of the National Clinical Research Center for Digestive Diseases (NCRC-DD), jointly awarded in 2014 by the Ministry of Science and Technology, National Health and Family Planning Commission of People’s Republic of China, and medical authority of Logistics Support Department, People’s Liberation Army.

NCRC-DD is a state-level medical center. It has established a nationwide clinical research collaborative network involving multi-level hospitals in China. The Clinical Epidemiology and Evidence Based Medicine (EBM) Unit of BFH-CMU provides methodological support and clinical research training for the NCRC-DD collaborative network.

Duke university school of medicine

The Duke University School of Medicine, established in 1925, is among the top medical schools in the USA and has one of the largest biomedical research enterprises in the USA [Citation8,Citation9]. The Duke Clinical Research Training Program (CRTP), founded in 1986, is a 2-year academic degree program in the Duke University School of Medicine that provides academic training in the quantitative and methodological principles of clinical research. The program is primarily designed for clinical fellows who are training for academic careers and offers formal courses in research design, research management, medical genomics, and statistical analysis [Citation10].

Program development

This specialized certificate-based program was designed and produced by Duke CRTP faculty in collaboration with an educational consulting firm experienced in the design, construction, testing, and delivery of eLearning. The primary components of the curriculum represent a core set of biostatistics and clinical research design principles and methods from the Duke CRTP degree program curriculum.

The certificate program is intended to provide clinicians and other health care professionals an introduction to the quantitative and methodological principles of clinical research. Key learning objectives of the program are to provide participants with the skills to (1) contribute to the design, implementation, analysis, and interpretation of clinical research studies; (2) critically evaluate research design and biostatistics aspects of research literatures published in the clinical research journals; (3) participate as collaborators in interdisciplinary clinical research teams.

Three experienced Duke CRTP faculty members led the BFH-Duke CRTP. All are collaborative clinical researchers and experienced teachers. Two have expertise in biostatistics and bioinformatics and one is a general internal medicine clinical faculty member. The key members of the Duke CRTP program and the methodology team of Clinical Epidemiology and EBM Unit, BFH-CMU were involved in the development of this collaborative program.

Participants

The BFH-Duke CRTP program is targeted to Chinese clinicians interested in improving their clinical research skills. Program recruitment information was advertised online. Program acceptance requirements were: 1) clinician with certain experience of clinical research; 2) less than 45 years old; 3) having a good skill in English reading and a certain communication skill in English; 4) available for five-day in-person workshop in Beijing.

Fifty clinicians were enrolled in the BFH-Duke CRTP on a first come enrollment basis. These participants were from nine cities or provinces of China, including Beijing, Hebei, Shanghai, Zhejiang, Fujian, Chongqing, Inner Mongolia, Jilin and Liaoning provinces (). The clinical specialties of participants included digestive diseases, liver diseases, cardiology, neurology, general surgery, liver transplantation, vascular surgery, urinary surgery, ophthalmology, ultrasonography, obstetrics and gynecology and intensive care. All participants were clinicians with experience of participating in clinical studies, and without statistical background/computer expertise. Participants were divided into ten structured teams that worked together throughout the program to develop a study proposal.

Figure 1. Geographic distribution of clinicians who attended the training program.

A total of 50 training program participants were from nine cities or provinces of China, including Beijing, Hebei, Shanghai, Zhejiang, Fujian, Chongqing, Inner Mongolia, Jilin and Liaoning provinces (Blue areas in the map). The in-person workshop was in Beijing (Red area in the map).

The structure of the training program

The BFH-Duke CRTP was comprised of three distinct, sequential learning components: Part 1 – a six-week online eLearning self-study, Part 2 – three weekly interactive synchronous webinars conducted between Durham, North Carolina and Beijing, China, and Part 3 – a five-day in-person workshop held at BFH-CMU in Beijing ().

Part1: online eLearning self-study

The objective of the online eLearning self-study was to become familiar with the basic principles of clinical research design and biostatistics. The eLearning modules were delivered via the TalentLMS (https://www.talentlms.com/) cloud-based learning management system (LMS). The eLearning curriculum was divided up into six on-demand weekly units, each requiring two to three hours to complete. Each unit addressed both research design and biostatistics topics that were delivered via multiple faculty narrated eLearning modules that included discussion of case studies from published research, primarily selected from studies conducted in China. The detailed topics included in the online eLearning structure are provided in supplementary Table 1.

At the end of each unit participants’ performance were measured by self-assessment multiple-choice quizzes as well as a written assignment that was submitted and reviewed by Duke faculty. Multiple choice questions were largely based on case-based excerpts from published open-access clinical research articles, the majority coming from articles publishing results of clinical research studies conducted in China. Assignments had a similar focus but required participants to read excerpts from articles (or articles in their entirety) and provide short written responses in English to questions about biostatistics or research design aspects of the studies in question.

Participants were required to view all eLearning modules and complete all quizzes and assignments before continuing to the next weekly unit. Participants had access to an online discussion forum as well as email support from program faculty. All eLearning modules were presented and narrated in English with English text and Chinese written translation provided side by side for better understanding of biostatistics and research design concepts.

Part 2: interactive synchronous webinars

Three weekly synchronous webinars were initiated after completion of the six online eLearning units in teleconference centers of Duke and BFH-CMU using CISCO hardware and the Webex platform (https://www.cisco.com/ & https://www.webex.com). The purpose of the webinars was twofold: to utilize case studies to apply principles learned during the eLearning self-study and to introduce the team-based project to develop a study proposal in response to one of two requests for proposals (RFPs). Lecture-demonstration by teacher and student-team reports were used as teaching methods in this part of the program. Each of the three webinars was offered three times during the week to accommodate the schedules of the participants and divide participants into smaller groups to facilitate more effective discussion. The webinar portion of the program had several team-based activities (e.g., pick a team name, choose which of several project topics to pursue) to build team rapport that participants completed but there were no quizzes, assignments, or other assessments. The webinars also discussed team-based research and fundamental principles in team interaction and dynamics. These activities were intended to give each 5-person team the opportunity to become acquainted and begin collaborating so that they would be ready for more team-based project activities during the workshop. Each webinar was approximately 75 minutes in length and held either in the early morning or late evening due to the 12-hour time difference between Durham and Beijing. Attendance was monitored and each webinar was recorded.

Part 3: five-day in-person workshop

The final part of the program was conducted in-person at BFH-CMU where the Duke faculty in partnership with five BFH-CMU teaching assistants (TAs) with expertise in Epidemiology and Biostatistics led a five-day workshop where participants worked on a team-based project to develop a clinical research study proposal. Task oriented discussion and presentations by student teams were used as teaching methods in this part of the program. The capstone activity of the workshop and program was development of a clinical research study proposal that included both written and oral presentation components. At the end of the workshop, each team submitted a written study proposal and delivered an oral presentation summarizing their proposal. The research proposal included the following components: research question, study outcomes, study design, data analysis plan, and study limitations. Program faculty supervised and participated in the discussion of team proposals and provided solutions to problems each team faced. Throughout the workshop, the TAs worked collaboratively with participant teams, providing feedback and guidance as they developed their study proposals.

Participants’ performance and participation evaluation

A survey was delivered to the participants at the end of the program using a survey delivered in an online questionnaire tool (Questionnaire Star) via WeChat messaging app (https://www.wechat.com/en/). Detailed information about development of the survey instrument can be found in the website (https://www.wjx.cn/app/survey.aspx). The structure of the delivered questionnaire included demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, professional title, English fluency, and years of work experience), research productivity (e.g., years of clinical research experience, number of Chinese and English Science Citation Index (SCI) publications), program characteristics (complexity of materials, program satisfaction, and financial value of training) and a free text feedback question on the overall evaluation of the training program.

In the section on satisfaction, participants were asked to report agreement with each statement on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The survey was developed and distributed in Chinese to facilitate understanding of the survey items. After data collection, the survey results were presented in English by the translation of the authors (supplementary Table 2). This program was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Friendship Hospital (No. 2018-P2-216-01).

The participants were divided into active and passive groups to account for differing levels of participation in the webinars and workshop. Active and passive participants were identified by the number of faculty interactions completed as a surrogate for participation in the classroom throughout the interactive synchronous webinars and workshop by TAs [Citation11]. Only participants who interacted with faculty equal to and more than once in any of the synchronous webinars and equal to and more than four times in the workshop were identified as ‘Active’. Other participants were identified as ‘Passive’ if they had no interaction in synchronous webinars or less than four interactions in workshop.

Statistical analysis

The quiz scores were calculated by the proportion of correct answers and the total number of quizzes. We used median and 1st quartile (Q1) – 3rd quartile (Q3) to describe the central tendency and dispersion for quantitative variables, such as the age, working years, clinical research years, SCI published articles, Chinese published articles and study time per week. The frequency (N) with the percentage (%) was used to describe categorical variables, such as gender, professional title, impact factor, oversea experiences, English communication ability, difficulty and satisfaction of the program, willingness to recommend and pay. Univariate logistic regression models were used to analyze the associations between degree of participation (active/passive) and potential influential factors, including gender, professional title, working years, total SCI index and other indicators of the capacity for scientific research. Modeling results are summarized using odds ratios (OR), confidence intervals (CIs), and p-values. Computation of confidence intervals was based on the profile likelihood.

Results

The response of all the participants

Forty-four participants (88%) answered the survey. The median ages were 34.0 years old and 32.5 years old for responders and non-responders. The male proportions were 17% and 45% in responders and non-responders. There were no statistically significant differences in age and gender between responders and non-responders.

Demographic characteristics of surveyed respondents

There were 20 (45%) male and 24 (55%) female clinicians, aged 34.0 (30.0-40.8) years old (). Seventeen (39%) participants of these young and middle-aged clinicians were associate or chief physicians (). As shown in and , the medians and IQR of their working years and clinical research years were 8 (Q1-Q3: 3–15) and 3 (Q1-Q3: 1–7), respectively. The medians of publications were 4 (Q1-Q3: 1–5) of SCI in English and 4 (Q1-Q3: 2–10) in Chinese. Thirty (68%) of the surveyed respondents had overseas experience, and 35 (80%) of the fellows could fluent or excellent state their opinion clearly in English ().

Table 1. Quantitative data of demographic characteristics of surveyed respondents (N = 44).

Table 2. Categorical data of demographic characteristics of surveyed respondents (N = 44).

Completion and participation rates

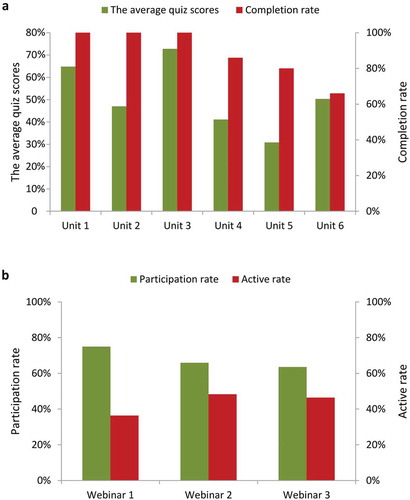

The average quiz scores in eLearning varied from 31% to 73% among the six units (). The completion rates for the first three units were 100%. However, the completion rates for unit 4 to unit 6 showed a decrement from 86% to 66%. The participation rates for the three webinars ranged from 64% to 75% (). All respondents attended the five-day face-to-face workshop. The factors that affected the active participation rates are shown in supplementary Table 3. Compared with participants who could only state their opinions with the help of translators, those with the ability to speak clear and fluent English had significantly higher participant activity (OR = 13.33, 95% CI: 1.41–321.37, p = 0.044).

Difficulty and satisfaction reported form surveyed respondents

As shown in , 5 surveyed respondents (11%) found the overall training courses as easy, 28 (64%) as neutral and 11 (25%) as difficult. Regarding the degree of difficulty of the three training components, there were 3, 14, and 11 respondents graded easy for online eLearning (7%), webinar (32%) and in-person workshop (25%), respectively. Around 50% of respondents graded neutral for webinar and in-person workshop, which was higher than 39% for online eLearning. Up to 55% of them deemed online eLearning to be difficult, which was higher than that of the synchronous webinars (18%) or in-person workshop (18%).

Table 3. Surveyed respondents’ ratings of overall difficulty of training program (N = 44).

Thirty-nine (89%) surveyed respondents showed satisfaction with the program, with the aspects in practical orientation, facilitators, materials, group work, and workshop. However, 5 surveyed respondents (11%) had a neutral attitude toward the content and frontier coverage in this program ().

Table 4. Surveyed respondents training program satisfaction results (N = 44).

Forty-three surveyed respondents (98%) indicated that they would recommend the program to their colleagues. While only the small percentage of individuals (n = 5, 11%) indicated willingness to pay >15,000 CNY, all remaining respondents (n = 39, 89%) valued the program at a minimum of 10,000–15,000 CNY ().

Table 5. Willingness to recommend and pay (N = 44).

Qualitative feedback from participants

The participants spoke highly of this training program. One participant evaluated this program as ‘Internet + interactive training’ and stated that offline face-to-face communication and operations helped provide him with a better understanding of study design. The fully prepared handouts and materials before the discussion, the importance of medical writing and effective presentation skills, and the well-prepared and engaged faculty made teaching and learning more substantive, beneficial and interesting.

There were 20 surveyed respondents (45%) providing 22 suggestions for further improvement of the course. The feedback from participants included three main aspects of suggestions to further improve the training courses (). Firstly, 7 (32%) commented on the degree of difficulty of the eLearning, suggesting that the content of this part could be further compressed for an introductory course and more practical examples could be added to better facilitate participant understanding. Secondly, 5 (23%) suggested on providing bilingual slides (narration scripts were provided in both English and Mandarin). Lastly, 5 (23%) suggested that the content of teaching should be more extensive and compatible with clinical practice. For example, they suggested expanding content related to meta-analysis and adding content related to procedures for registering clinical trials on https://clinicaltrials.gov/.

Table 6. Surveyed respondents feedback (N = 22).

Discussion

The certificate-based international collaborative training program was innovative in its use of a blended learning approach that included an online eLearning self-study, synchronous webinars, and a five-day in-person workshop. To our knowledge, this is the first manuscript to comprehensively describe the development process and the structure of the multimodal training program.

The infrastructure of online eLearning and synchronous webinar modules of the program described in this study were similar to the previous ICRT-Japan program [Citation1,Citation12], but with a more detailed introduction on the curriculum design, delivery method, duration and teaching method. Furthermore, we adopted a different approach to mentorship in face-to-face workshops.

The three distinct, sequential learning components delivered by BFH-Duke CRTP worked well in China. The results in evaluating the difficulties among the multimodal program demonstrated that most of the participants felt that the webinars and workshop were less difficult than the eLearning. As suggested by the open-ended feedback, this may be related to the focus of the eLearning on the basic foundations of epidemiology and biostatistics, which are relatively unfamiliar topics to the clinicians. Additionally, unlike the eLearning which was completed individually, participants worked in teams during the webinars and workshop to complete a research proposal which is more familiar to them since all have at least some previous clinical research experience.

Online and Offline (OAO) teaching mode was performed in this international collaborative training program. Over the past decades, the interest in medical education and clinical research training has increased dramatically [Citation13,Citation14], particularly in demand for international training of clinical research [Citation15,Citation16]. Novel project-based learning and research models arising from online learning have emerged with the development of the Internet, such as massive open online courses (MOOCs), creating opportunities for global education and research to address real-world challenges [Citation17–Citation19]. Though online eLearning has its own advantages, we found that offline interaction could be another feasible mode in curriculum development.

Mentorship was an important part in the training program. As Rezhake et al [Citation7] and Shah SK et al [Citation20] previously referred, effective mentoring offers opportunities to guide careers of medical researchers. We also discussed and addressed this critical issue during program development, the three fixed Duke faculty helped refine research questions and impart knowledge of clinical research. Five fixed BFH-CMU TAs with expertise in epidemiology and biostatistics worked collaboratively with participant teams, providing feedback and guidance as they developed their study proposals. The mentorship from the faculty and TAs of this training program could suggest appropriate post-program research directions for participants.

In international medical education, a Four-Component Instructional Design model (4C/ID), which emphasize part-task practice has been widely used [Citation21,Citation22]. Skills and knowledge, although taught, faced barriers including the difficulty in transferring to clinical practice [Citation23]. BFH-Duke CRTP included some illustrative examples of educational practices. However, participants’ feedback suggested more practical examples in study design and statistical analysis should be given priority.

There are several potential limitations to consider when interpreting our findings. First, as all participants had some experience with and interest in clinical research, selection bias may affect the generalizability of this program. Second, as this was a cross-sectional survey, we could not obtain objective performance indicators, such as oral presentations at meeting (national/international), papers (cumulative impact factor and total number of first author papers), implementation of research projects and grants in this program, so a follow-up longitudinal survey will be conducted to collect objective performance indicators [Citation24]. Third, it might be an important consideration of language barriers in international collaborative training programs. Though all the participants in this program were able to read and write in English, the ability of English communication might still be a critical barrier for discussion in the interactive modules of this program. The inclusion of both faculty and TAs fluent in Mandarin was a deliberate program decision to address this concern. Fourth, the limited number of participants might influence substantial assessment of this program. Further studies are justified to generalize this mode to other international training programs.

Conclusions

BFH-Duke CRTP established a multimodal international collaborative training program. This program could serve as a model for other similar international training programs for physicians and health professionals seeking to improve their clinical research skills.

Authors’ contribution

The conception and design of the work: Steven Grambow, Yuanyuan Kong, Shutian Zhang, Youqing Xin, Hong You and Jidong Jia;

The acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the work: Qian Zhang, Yu Shi, Na Zeng, Shanshan Wu, Wei Wei, Min Li and Mo Liu;

Drafting: Qian Zhang and Yu Shi;

Revision critically for important intellectual content: Na Zeng, Shanshan Wu, Wei Wei, Min Li, Mo Liu, Hong You, Jidong Jia, Shutian Zhang, Youqing Xin, Yuanyuan Kong and Steven Grambow;

Final approval and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: All authors.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (52.4 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank Lisa Bourget, MBA, Senior Director, Strategy, Management, and Partnerships, Duke Global Health Innovation Center and Arthur Huang, MBA, Senior Manager, Programs, Duke Global Health Innovation Center for helping with establishing collaboration on BFH-Duke CRTP. We thank Sheng Luo, PhD, Associate Professor of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics and John Williams, MD, Professor of Medicine, from Duke University for participating as training program faculty and Michelle Evans from Duke University for assistance with program planning and management. We thank Bill Wilkinson, PhD, Professor Emeritus of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, and founding director of CRTP who collaborated on the development of the eLearning curriculum for the program with consulting support from Jerry Gschwind, a senior learning strategy consultant with Symphony Learning Partners and Patrick Sloan, a multimedia Design and eLearning Advisor with Element Learning. We thank Qiuping Li and Guiling Dong for their contribution to the management of CRTP in China. We thank the Department of Science and Technology, Medical Department, Information Department and Education Department of Beijing Friendship Hospital for the help with the smooth running of CRTP in China. We also thank all the participants for taking their time to respond to the questionnaire.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the other authors.

Data availability statement

The main data used to support the findings of this program is included within the article. The datasets generated and analyzed during the current program are available from the corresponding author (Yuanyuan Kong, [email protected]) on reasonable request.

Supplementary material

Supplemantal data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Carvas M, Imamura M, Hsing W, et al. An innovative method of global clinical research training using collaborative learning with Web 2.0 tools. Med Teach. 2010;32(3):270.

- Sandercock P, Whiteley W. How to do high-quality clinical research 1: first steps. Int J Stroke. 2018;13(2):121–9.

- Kurita N, Murakami M, Shimizu S, et al. Preferences of young clinicians at community hospitals regarding academic research training through graduate school: a cross-sectional research. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:227.

- cited 2018 Oct 8. Available from: http://www.cma.org.cn/attachment/201536/1425610435081.pdf

- cited 2019 May 18. Available from: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/NE6s8PGbbYptmRaev-yowA

- Heimburger DC, Carothers CL, Blevins M, et al. Impact of global health research training on scholarly productivity: the fogarty international clinical research scholars and fellows program. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93(6):1201–1207.

- Rezhake R, Hu SY, Zhao YQ, et al. Impact of international collaborative training programs on medical students’ research ability. J Cancer Educ. 2018;33(3):511–516.

- cited 2019 Jan 8. Available from: https://medschool.duke.edu/about-us

- cited 2019 Jan 8. https://medschool.duke.edu/research

- Armstrong AY, Decherney A, Leppert P, et al. Keeping clinicians in clinical research: the clinical research/reproductive scientist training program. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(3):664–666.

- Abdullah MY, Abu Bakar NR, Mahbob MH. Student’s participation in classroom: what motivates them to speak up? Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2012;51:516–522.

- cited 2019 Aug 8. https://postgraduateeducation.hms.harvard.edu/certificate-programs/open-enrollment-programs/introduction-clinical-research-training-japan

- Drain PK, Primack A, Hunt DD, et al. Global health in medical education: A call for more training and opportunities. Acad Med. 2007;82(3):226–230.

- Drain PK, Holmes KK, Skeff KM, et al. Global health training and international clinical rotations during residency: current status, needs and opportunities. Acad Med. 2009;84(3):320–325.

- Scarlett HP, Nisbett RA, Stoler J, et al. South-to-north, cross-disciplinary training in global health practice: ten years of lessons learned from an infectious disease field course in Jamaica. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85(3):397–404.

- Walker RJ, Campbell JA, Egede LE. Effective strategies for global health research, training and clinical care: a narrative review. Glob J Health Sci. 2014;7(2):119–139.

- Reich J. Education research. Rebooting MOOC research. Science. 2015;347(6217):34–35.

- Ruiz de Castañeda R, Garrison A, Haeberli P, et al. First ‘global flipped classroom in one health’: from MOOCs to research on real world challenges. One Health. 2018;5:37–39.

- Hossain MS, Shofiqul Islam M, Glinsky JV, et al. A massive open online course (MOOC) can be used to teach physiotherapy students about spinal cord injuries: a randomised trial. J Physiother. 2015;61(1):21–27.

- Shah SK, Nodell B, Montano SM, et al. Clinical research and global health: mentoring the next generation of health care students. Glob Public Health. 2011;6(3):234–246.

- Janssen-Noordman AM, Merriënboer JJ, van der Vleuten CP, et al. Design of integrated practice for learning professional competences. Med Teach. 2006;28(5):447–452.

- Vandewaetere M, Manhaeve D, Aertgeerts B, et al. 4C/ID in medical education: how to design an educational program based on whole-task learning: AMEE Guide No. 93. Med Teach. 2015;37(1):4–20.

- Maggio LA, Cate OT, Irby DM, et al. Designing evidence-based medicine training to optimize the transfer of skills from the classroom to clinical practice: applying the four component instructional design model. Acad Med. 2015;90(11):1457–1461.

- Knapke JM, Tsevat J, Succop PA, et al. Publication track records as a metric of clinical research training effectiveness. Clin Transl Sci. 2013;6(6):458–462.