ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives

It is well established that provider lack of knowledge in the field of transgender and nonbinary health is as ignificant barrier to care and that training in this area is lacking. This study examined how family medicine residents’ self-confidence and medical knowledge in providing gender-affirming care changed after completing a novel, online curriculum on transgender and nonbinary care.

Methods

Thirty-nine family medicine residents were invited to complete the curriculum. Change inself-confidence was determined by the difference in scores on a Likert scale on a pre- and post-survey. Change in medical knowledge was assessed by examining the difference between pre- and post-test scores on a novel multiple-choice examination.

Results

Only 7% of current residents agreed that their current training is adequate in order to provide comprehensive primary care to transgender and nonbinary people. After completion of the curriculum, 100% of participants felt at least somewhat confident providing primary care to transgender and nonbinary people, including hormone therapy. Average medical knowledge post-test scores trended higher than the pre-test results (mean (SD) at pre = 11.2 (1.4) vs post = 14.6 (2.8)).

Conclusions

An online, self-directed curriculum on caring for transgender and nonbinary patients in the primary care setting, including management of gender-affirming hormone therapy, has the potential to increase confidence and knowledge in this field, decreasing barriers to care for this population.

Introduction

Provider lack of knowledge in the field of transgender and nonbinary health is a major barrier to care, and while the need for curricula covering transgender care has been increasingly recognized, there continues to be significant gaps in undergraduate and graduate medical education and training in this field [Citation1–9]. This is pervasive across disciplines as evidence demonstrates lack of training in numerous specialties [Citation9–18]. Lack of provider knowledge leads to greater stigma, discrimination, and delays in care for this patient population, emphasizing the importance of increased education in this field [Citation2,Citation5].

While gender-affirming care is considered medically necessary care and within the scope of primary care practice, there continues to be a lack of standard education in this area in primary care training [Citation19–24]. There is untapped potential to increase the primary care workforce that can provide high-quality care to the estimated 0.5% of adults, or about 1.3 million people, in the United States who identify as transgender [Citation25].

This study examines the effect of a self-directed, online curriculum on transgender care, including initiation of gender-affirming hormone therapy, on confidence and medical knowledge of family medicine residents. In graduate medical education, there have been several effective educational interventions studied in this area, although some are limited by a lack of long-term outcomes [Citation16,Citation26–28]. However, no study to date has evaluated the effectiveness of an online intervention with family medicine residents as the targeted learners.

Methods

The researchers conducted a single group, pre-posttest study in which they implemented a novel, online curriculum covering transgender care within a family medicine residency in the midwestern United States and assessed change in self-confidence in providing gender-affirming care as well as medical knowledge. All 39 residents of the program were invited to complete the curriculum. The study was exempt from review by the University of Michigan and Johns Hopkins University institutional review boards (UM HUM00183779; JHU HIRB00011650).

The curriculum was developed with a multidisciplinary team of content-area experts. The modules covered the following topics: foundational concepts; health disparities and lived experiences; behavioral health; adult gender-affirming hormone therapy; child and adolescent gender care; gender-affirming surgery and other interventions; and health maintenance, cancer screening, and reproductive considerations (Appendix A).

Prior to the curriculum, current residents and recent graduates (graduated within five years prior to the study period) answered survey questions assessing their willingness to provide gender-affirming care, confidence providing gender-affirming care, transgender clinical exposure, and adequacy of training in order to practice gender-affirming care. A similar survey was administered to participants after completion of the curriculum.

Knowledge was assessed using a series of multiple choice questions regarding gender-affirming care. As there are no validated tools to measure knowledge in this field, the exams were created with the input of both content-area and educational experts.

Changes in knowledge and confidence were assessed by comparing responses between the pre- and post-tests and surveys. Pre- and post-data were treated as independent, and descriptive statistics were compared. Finally, the content and administration of the curriculum, as well as whether it will change participants’ practice, were also evaluated with a single group post-survey.

Results

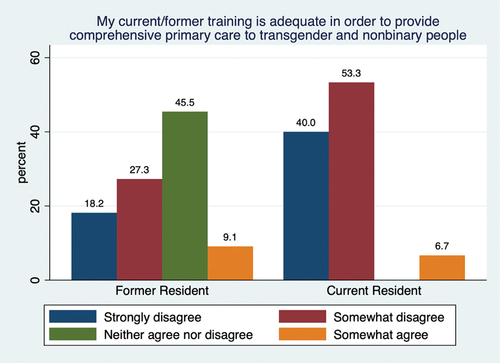

Fifteen current and 11 former residents completed the pre-survey, and 10 current residents completed the post-survey. All participants were willing to provide care to transgender patients, and the importance of providing gender-affirming care was ranked highly among former and current residents, with six respondents choosing ‘agree’ and the remaining responding ‘strongly agree.’ Many former residents expressed neutrality or disagreed that their training was adequate to provide primary care to this population, and most of the current residents who completed the pre-survey did not feel their current training was adequate ().

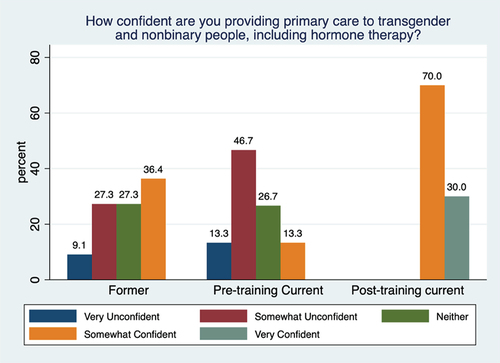

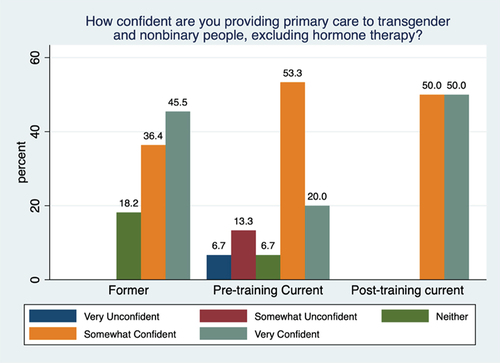

In the post-survey, confidence in providing primary care to transgender patients, excluding hormone therapy, was split between ‘somewhat confident’ and ‘very confident’ (). Pre-curriculum responses had several respondents select ‘very unconfident,’ ‘somewhat unconfident,’ and ‘neither confident nor unconfident’ (). Pre-survey responses leaned towards ‘somewhat’ or ‘very unconfident’ regarding providing primary care including gender-affirming hormone therapy (). For residents who completed the post-survey, the majority were at least ‘somewhat confident’ and 30% were ‘very confident’ ().

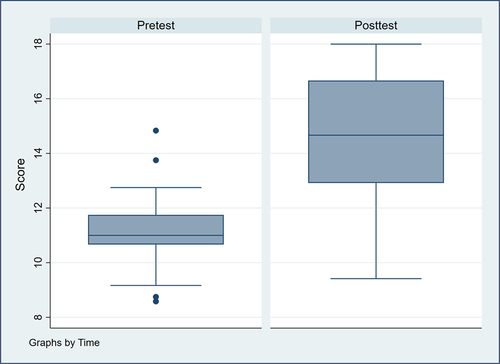

There were 25 medical knowledge tests taken pre-training and 11 taken post-training (64.1% and 28.2% response rates). Post-test scores tended to be higher than the pre-test results (mean (SD) at pre = 11.2 (1.4) vs post = 14.6 (2.8)) ().

Finally, the curriculum assessment was completed by eight current residents who finished the online training, and responses were overwhelmingly positive. Individuals reported how their practice would be changed and provided suggestions for additional attention to particular topics, included in .

Table 1. Quotes from curriculum assessment.

Discussion

The proportion of residents who were ‘very confident’ in providing gender-affirming primary care excluding hormone therapy increased from 20% to 50% of the respondents, suggesting that the curriculum improved confidence in this area. The curriculum also had a positive impact on confidence managing gender-affirming hormone therapy: a minority of former residents and current residents prior to completion of the curriculum felt ‘somewhat confident’ providing this care, while none felt ‘very confident’; however, after completion of the curriculum, all residents responded that they felt at least ‘somewhat confident’ providing care including hormone therapy ().

The findings suggest that medical knowledge increased after completion of the curriculum, showing that the online curriculum has the potential to change both confidence and knowledge. Finally, the curriculum was very well received as reported in narrative feedback. Given the positive feedback, the ease of implementation, and no financial cost of the online platform, this study depicts a promising method of implementing education and training on this topic to residents.

Several limitations exist, including low participation size, which could be improved with incentivization. The decline in number of participants who completed the post-test as compared to the pre-test could be due to several factors including time limitations, but those who completed the post-test may have a particular interest in gender-affirming care, skewing the results favorably. Furthermore, the study was conducted in one residency program in the United States, and the generalizability of the results would have been much stronger if the study was conducted with multiple programs from diverse areas. Other limitations include that the pre- and post-survey and medical knowledge results were not matched, and the medical knowledge test has not been validated. Finally, the study would have ideally included long-term outcomes as well as a clinical skills component. However, the vast majority of respondents strongly agreed the curriculum would change their practice.

We aim to address the barriers to care this population endures by increasing the primary care workforce that can provide high-quality care to transgender patients. Future areas of inquiry include testing the curriculum at other training sites, incorporating clinical skills as another measure of effectiveness, and long-term outcomes of this curriculum on knowledge and confidence as well as clinical practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Coutin A, Wright S, Li C, et al. Missed opportunities: are residents prepared to care for transgender patients? A study of family medicine, psychiatry, endocrinology, and urology residents. Can Med Educ J. 2018;9(3):e41–6. doi: 10.36834/cmej.42906

- de Vries E, Kathard H, Müller A. Debate: why should gender-affirming health care be included in health science curricula? BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-1963-6

- Dubin SN, Nolan IT, CG S Jr, et al. Transgender health care: improving medical students’ and residents’ training and awareness. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:377–391. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S147183

- Greene MZ, France K, Kreider EF, et al. Comparing medical, dental, and nursing students’ preparedness to address lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer health. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0204104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204104

- Jaffee KD, Shires DA, Stroumsa D. Discrimination and delayed health care among transgender women and men: implications for improving medical education and health care delivery. Med Care. 2016;54(11):1010–1016. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000583

- Korpaisarn S, Safer JD. Gaps in transgender medical education among healthcare providers: a major barrier to care for transgender persons. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2018;19(3):271–275. doi: 10.1007/s11154-018-9452-5

- Lehman JR, Diaz K, Ng H, eds. The equal curriculum: the Student and educator Guide to LGBTQ health. New York City (NY): Springer International Publishing; 2020.

- Safer JD, Coleman E, Feldman J, et al. Barriers to healthcare for transgender individuals. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23(2):168–171. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000227

- Shires DA, Stroumsa D, Jaffee KD, et al. Primary care clinicians’ willingness to care for transgender patients. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(6):555–558. doi: 10.1370/afm.2298

- Fisher WS, Hirschtritt ME, Haller E. Development and implementation of a residency area-of-distinction in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender mental health. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(4):564–566. doi: 10.1007/s40596-017-0847-5

- Johnston CD, Shearer LS. Internal medicine resident attitudes, prior education, comfort, and knowledge regarding delivering comprehensive primary care to transgender patients. Transgend Health. 2017;2(1):91–95. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2017.0007

- Moll J, Krieger P, Moreno-Walton L, et al. The prevalence of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health education and training in emergency medicine residency programs: what do we know? Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(5):608–611. doi: 10.1111/acem.12368

- Morrison SD, Dy GW, Chong HJ, et al. Transgender-related education in plastic surgery and urology residency programs. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(2):178–183. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00417.1

- Stevenson MO, Sineath RC, Haw JS, et al. Use of standardized patients in endocrinology fellowship programs to teach competent transgender care. J Endocr Soc. 2019;4(1):bvz007. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvz007

- Streed CG Jr, Hedian HF, Bertram A, et al. Assessment of internal medicine resident preparedness to care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(6):893–898. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04855-5

- Ufomata E, Eckstrand KL, Spagnoletti C, et al. Comprehensive curriculum for internal medicine residents on primary care of patients identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10875. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10875

- Vance SR Jr, Buckelew SM, Dentoni-Lasofsky B, et al. A Pediatric transgender medicine curriculum for multidisciplinary trainees. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10896. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10896

- Vinekar K, Rush SK, Chiang S, et al. Educating obstetrics and gynecology residents on transgender patients: a survey of program directors. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(4):691–699. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003173

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Recommended curriculum guidelines for family medicine residents: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender health. [cited 2021 May 18]. Available from: https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/medical_education_residency/program_directors/Reprint289D_LGBT.pdf

- World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-conforming people [8th version]. 2022. https://www.wpath.org/publications/soc.

- UCSF Transgender Care, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of California San Francisco. Guidelines for the primary and gender-affirming care of transgender and gender nonbinary people. Deutsch MB. ed. 2nd edition. 2016; https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Implementing curricular and institutional climate changes to improve health care for individuals who are LGBT, gender nonconforming, or born with DSD. Hollenbach, AD, Eckstrand, KL, Dreger, A, eds.; 2014. https://store.aamc.org/downloadable/download/sample/sample_id/129/

- Safer JD, Tangpricha V. Care of the transgender patient. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(1):ITC1–ITC16. doi: 10.7326/AITC201907020

- Care for the Transgender and gender nonbinary patient. AAFP Policy Statement. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/transgender-nonbinary.html

- The Williams Institute. How many adults and youth identify as transgender in the United States? Herman, JL, Flores, AR, O’Neill, KK, eds.; 2022. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Trans-Pop-Update-Jun-2022.pdf

- Kidd JD, Bockting W, Cabaniss DL, et al. Special-“T” training: extended follow-up results from a residency-wide professionalism workshop on transgender health. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(5):802–806. doi: 10.1007/s40596-016-0570-7

- Thomas DD, Safer JD. A simple intervention raised resident-physician willingness to assist transgender patients seeking hormone therapy. Endocr Pract. 2015;21(10):1134–1142. doi: 10.4158/EP15777.OR

- Vance SR Jr, Lasofsky B, Ozer E, et al. Teaching paediatric transgender care. Clin Teach. 2018;15(3):214–220. doi: 10.1111/tct.12780

AppendicesAppendix A: Learning Objectives

After completion of the online curriculum, family medicine residents will achieve the following (unless otherwise noted, listed objectives will be measured by change in scores on pre- and post-test):

Foundational Concepts – Sara Wiener, LMSW

1. Gain awareness of major evidence-based guidelines used to care for transgender and nonbinary (TGNB) individuals.

2. Define essential terminology used to classify identities across the gender spectrum.

3. Appreciate the importance of using a person’s pronouns.

4. List a variety of ways to create a safe and supportive health care environment for individuals of all gender identities.

5. Understand that differences in gender identity and expression are not pathological.

6. Recognize treatment practices that are unethical and/or problematic, such as treatment that attempts to change a person’s gender identity to align with sex at birth.

Health Disparities and Lived Experiences – Sara Wiener, LMSW

7. Describe the ways that stigma affects the TGNB population and the documented positive impact of social support on the well-being of TGNB people.

8. Describe health disparities, including mental health disparities, among the TGNB population.

9. Identify the critical role of advocacy and current policy issues that affect TGNB individuals.

10. Demonstrate knowledge of appropriate documentation needed for name or sex change on official documents.

Behavioral Health – Sara Wiener, LMSW

11. Understand how and when to utilize mental health clinicians when caring for TGNB individuals.

Child and Adolescent Gender Care – Dan Shumer, MD

12. Demonstrate understanding of the fundamental tenets of gender-affirming hormone therapy for children and adolescents. Learners will be expected to demonstrate knowledge of the following components:

a. Standards of care for initiating therapy

b. Fundamental components of a gender history

c. Main forms of GnRH agonists (‘puberty blockers’), possible side effects, and monitoring

d. Main forms of both masculinizing and feminizing hormone therapy, including how and when to initiate therapy, possible risks or side effects of therapy, indications for consultation of a sub-specialist including relative contraindications of hormone therapy, permanent and reversible changes associated with therapy, monitoring lab work after initiation, and when to expect physical change

Adult Gender-affirming Hormone Therapy – Julie Blaszczak, MD, MEHP

13. Demonstrate understanding of the fundamental tenets of gender-affirming hormone therapy for TGNB adults. Learners will be expected to demonstrate knowledge of the following components:

a. Standards of care for initiating hormone therapy, including the shared decision making model

b. Fundamental components of a gender history

c. Main forms of feminizing hormone therapy, including initiation and titration of estradiol and anti-androgens, monitoring lab work after initiation, possible risks or side effects of therapy, indications for consultation of a sub-specialist including relative contraindications of hormone therapy, permanent and reversible changes associated with therapy, and when to expect physical change

d. Main forms of masculinizing hormone therapy, including initiation and titration of testosterone, monitoring lab work after initiation, possible risks or side effects of therapy, indications for consultation of a sub-specialist including relative contraindications of hormone therapy, permanent and reversible changes associated with therapy, and when to expect physical change

e. Methods of inducing amenorrhea in transmasculine individuals as well as basic evaluation of persistent menses

Gender-affirming Surgery and Other Interventions – Julie Blaszczak, MD, MEHP

14. Briefly describe the various forms of gender-affirming surgeries available to TGNB individuals, including possible post-op complications.

15. Recognize other gender-affirming interventions including, but not limited to, hair removal and speech therapy.

Health Maintenance, Cancer Screening, and Reproductive Considerations – Anita Hernandez, MD

16. Demonstrate knowledge of the appropriate health maintenance and cancer screening required for TGNB individuals.

17. Understand reproductive considerations prior to and after starting gender-affirming hormone therapy, including contraceptive counseling.