ABSTRACT

Introduction

The career choices of medical graduates vary widely between medical schools in the UK and elsewhere and are generally not well matched with societal needs. Research has found that experiences in medical school including formal, informal and hidden curricula are important influences. We conducted a realist evaluation of how and why these various social conditions in medical school influence career thinking.

Methods

We interviewed junior doctors at the point of applying for speciality training. We selected purposively for a range of career choices. Participants were asked to describe points during their medical training when they had considered career options and how their thinking had been influenced by their context. Interview transcripts were coded for context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) configurations to test initial theories of how career decisions are made.

Results

A total of 26 junior doctors from 12 UK medical schools participated. We found 14 recurring CMO configurations in the data which explained influences on career choice occurring during medical school.

Discussion

Our initial theories about career decision-making were refined as follows: It involves a process of testing for fit of potential careers. This process is asymmetric with multiple experiences needed before deciding a career fits (‘easing in’) but sometimes only a single negative experience needed for a choice to be ruled out. Developing a preference for a speciality aligns with Person-Environment-Fit decision theories. Ruling out a potential career can however be a less thought-through process than rationality-based decision theories would suggest. Testing for fit is facilitated by longer and more authentic undergraduate placements, allocation of and successful completion of tasks, being treated as part of the team and enthusiastic role models. Informal career guidance is more influential than formal. We suggest some implications for medical school programmes.

Introduction

The proportions of medical graduates who chose particular careers varies widely between medical schools [Citation1–5] and, overall, graduates’ career choices are not well matched with societal needs [Citation6,Citation7]. Although there have been initiatives to better match career choices with societal needs, in particular the proportion who opt to become general (or family) practitioners [Citation7–9], most medical schools do not aim for their graduates to enter particular specialities. Nevertheless, medical students’ career preferences often alter while at medical school and alter in different ways at different medical schools [Citation10]. Only about one in four US medical students who started medical school with a career in mind chose the same speciality on graduating in 2022 [Citation11].

This variation in graduates’ career choices between medical schools highlights the importance of understanding the role of learning environments on the career choice process. There is evidence that some curriculum configurations seem to be associated with a greater understanding and likelihood of particular career choices but we do not have a clear theory of how this works. Students who have early clinical experience in community settings may have a greater understanding of societal needs and the role of general practitioners [Citation12]. High-quality placements in which students engage with authentic clinical activity are major attractors to a speciality [Citation13,Citation14] and an association has been found between the total time spent in primary care placements and likelihood of choosing a career in general practice [Citation2,Citation15] but not for psychiatry, surgery or anaesthetics [Citation2]. Students who undertake extended rural placements were more likely than students from a rural background to choose an internship in a rural area [Citation16]. These findings warrant explanation.

Informal and hidden curricula at medical school can also influence career choice. Negative comments from academic staff, doctors and other students about psychiatry and general practice influenced up to 50% of students in one study to choose another career [Citation17]. Almost two thirds of medical students at one school perceived general practice to have lower status than hospital specialities and almost half felt that their medical school culture had influenced this view [Citation18]. Foundation (PGY1) doctors have similar views [Citation19]. These negative perceptions of general practice are long standing and widespread [Citation20,Citation21].

Career choice is a personal decision, and although influential factors have been identified, the process is not well understood. Rational choice theories of decision-making such as subjective expected utility theory (SEU) have been used to try to understand the process in medical students in the United States [Citation22]. SEU posits that an individual considers the appeal of each career available to them (its utility) and weighs each choice by their subjective judgement of the likelihood of succeeding in each and that such choices are rational taking into account the decision-maker’s resources, consequences of the choice and a logical consideration of likelihood [Citation22]. The context differs in the UK where a state-funded healthcare system limits specialty earning potential and differentials, thus flattening one element of utility in SEU. Also the requirement to complete a 2-year period of generic postgraduate training (Foundation Programme), ahead of eligibility to apply for specialty training may make medical students view career choice differently. Career thinking is however encouraged in UK medical schools, students may well consider how to improve their medical specialty competitiveness and tools based on Person-Environment-Fit theories of career decision-making [Citation23,Citation24] such as Sci59 [Citation25] have been used to guide medical student career thinking. The theoretical proposition that medical career decisions are made by matching personal needs with perceptions of speciality characteristics was supported by a systematic review of educational systems with a Western European curriculum structure [Citation26]. Nevertheless, theories of career choice are insufficient unless contextual factors such as cultural [Citation27] and social [Citation17–19] influences on career decision-making are also included. Bounded rationality models of choice in economics [Citation28] would have it that individuals choose satisfactory results instead of the best, and although rational, they base their choice on what (limited) information is available to them and on their (easily biased) mental capabilities. This might apply to career thinking. For example, medical student perceptions of specialities may be skewed by the exposure students have to different specialities and to different role models within them [Citation14,Citation29].

Career decision-making processes are clearly complex and evolve gradually during and after medical school. The literature suggests that while the process of career decision-making is not well understood, experiences in medical school including formal exposure and informal and hidden curricula are important. While acknowledging that other factors in an individual’s life also affect their career choice, medical educators should be aware of the influence we have. We need more research into the psychological process of how and why careers are chosen under these various social conditions. As undergraduate medical educators we deliberately chose to focus on the learning environment as being the context we can change. We set out to improve our understanding of how medical school learning environments influence graduates’ eventual career choices. This matters. Medical schools need evidence as to how they can help students make good choices between available opportunities and to help students think about how well those choices ‘fit’ their attributes and needs. This understanding could inform how curricula, policy and practice might be altered in order to contribute towards filling the intended number of training posts with doctors who are best suited, potentially reducing the current problems of imbalances and drop-outs.

This study was approved by the School of Medicine Ethics Committee June 2015

Methods

Aim

To improve understanding of how medical school learning environments and curricula influence graduates’ eventual career choices.

Objectives

To conduct a realist evaluation of the experiences that junior doctors recall as being important to their career choice, with a focus on influences and events in medical school.

To produce recommendations for medical school formal and informal curricula

Theoretical orientation

We chose realist evaluation because it is suitable for studying complex human programmes such as medical education and seeks to explain causal links between context and outcomes rather than simply describing the factors considered to be influencing outcomes. Realist evaluation asks ‘What works for whom under what circumstances, in what respects and why?’ and develops theories (often in the form of Context-Mechanism-Outcome (CMO) configurations) that seek to explain causation from what participants say about their experiences [Citation30,Citation31]. A realist approach is theory-driven, starting with theories to be tested, and interprets data to develop these hypotheses with an explicit eye for the way context affects whether and how individuals react in certain semi-predictable ways (mechanisms) to produce the outcomes of interest. Programmes (interventions) work by changing participants’ decisions ([Citation30], p. 66). Recurring CMO configurations are examples of Middle Range Theories (MRTs), explaining how and why an intervention works and the influence on this of other elements in the context. While MRTs require ‘abstraction [they] … should be close enough to observed data to be incorporated in propositions that permit empirical testing’ and can be refined by subsequent analysis ([Citation32], p. 39). By making the relationships between context mechanisms and outcomes explicit, an ‘Initial Programme Theory’ about these relationships is refined to set out a ‘Final Programme Theory’ which can be used to provide targeted suggestions for adjustment of the complex intervention under study [Citation31]. We have used the RAMESES II standards for reporting realist evaluations to report this work [Citation33].

The initial programme theory for a realist evaluation is often drawn from the guiding documents of the programme being studied. In studying the influence on career choice of UK medical schools, the stated aim of undergraduate medical programmes is to produce doctors who are capable of any medical career. Career information and advice is however part of what UK medical schools are required to provide [Citation34] but little guidance on how this is done is provided. This lack of prescription may be why the informal curriculum about career choice is important [Citation18,Citation21,Citation26].

Our initial programme theory (about how career choice is made) was constructed by four members of the research team (JL RK RM SY) in a series of 5 meetings over 2 months drawing on our various understandings of career decision-making including our own and our students’ and junior colleagues’ experiences, SEU and Person-Environment-Fit theories, socio-cultural theories of experiential learning in workplaces [Citation35] and an exploratory search of relevant literature about career decisions in medical students and graduates as outlined in the introduction.

Initial programme theory

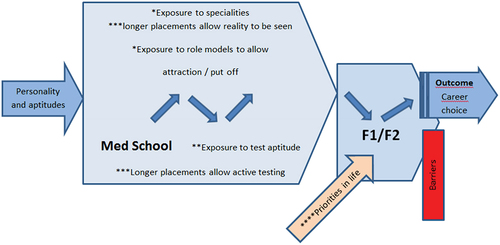

provides a visual representation of our agreed initial programme theory.

Recruitment and selection

This is an extension to a previously reported study [Citation36,Citation37] of the transition from being a medical student to being a doctor. Those who consented to their initial transition into practice being studied in 2015 were invited to consent to further follow-up a year later (FY2 or PGY2) when they were applying for speciality training and had hence made a firm career decision. Additional participants at the same career stage were recruited from the local Foundation School by email, by advertising at training days and from other Foundation Schools via ad hoc contacts. Potential respondents were asked to categorize their chosen career as ‘General practice’, ‘Hospital practice’ (medical and surgical specialities, anaesthetics, imaging and pathology) and ‘Other’ (public health and psychiatry) and we then purposively sampled respondents by career choice to ensure representation of a range of career choices. Interviews were conducted in 2017 and 2018.

Data generation

We wished to elicit explanations of doctors’ career choices by asking them to recall times before, during and since medical school when they considered particular careers and try to identify what had triggered those thoughts and how they were influenced. For the purposes of this study, the main focus of the interview was on their time at medical school. To this end, we used semi-structured interviews to explore the participants’ decision-making. We used telephone interviews because participants were scattered across the UK and scheduled these to suit participants. Interviews were conducted by HT and AT who used an interview framework consisting of 5 open questions with follow-up probing questions to guide their interviews (see Appendix). HT and AT were clinical teaching fellows at the local medical school and neither knew the participants nor were involved in their career progression. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by an independent transcription service. During transcription, all data was made anonymous for analysis by the authors and for publication.

Data analysis

Realist evaluation is an ‘iterative explanation-building process’ (pg 93 [Citation30]). For each transcript, two members of the research team identified and coded CMO configurations in the text in which career thinking was described. AT coded all the transcripts and one or other of the team members independently coded each transcript. They then discussed in researcher meetings differences of coding and agreed what was being described and how it should be coded. They extracted recurring CMO configurations into a spreadsheet with their accompanying quotes. CMO configurations were grouped in the spreadsheet by sub-sections of the Initial Programme Theory. Any CMO configurations which did not fit were put into a ‘basket’ column for further analysis to determine whether there was scope to develop new theory. The CMO configurations in each column of the spreadsheet were analysed to refine theory. Quotes were labelled by the participants Medical School (K for home, N for other), the serial code for the transcript and the participant sex eg K15F.

Results

We recruited 46 FY2 doctors (eight from the original study cohort and another 11 local and 27 graduates of other UK medical schools) who all provided data about their career preference on entry to medical school and at recruitment to the study (FY2). From these recruits we sampled purposively to get a spread of interviews of those choosing GP and other careers. Our final sample of 26 participants included the eight volunteers from the original study cohort plus another five local and 13 graduates from 11 other UK schools. For six of them, career preference was unchanged since entering medical school. Ten had changed preference during medical school and ten recalled no career preference at entry to medical school. Although all participants had stated career choice at recruitment, at interview two participants revealed they did not have firm career preferences and three were considering delaying entry to speciality training. This trend to take a training break at the end of foundation training rather than continuing with specialty training immediately is recognised [Citation38,Citation39] and is designated ‘F3’ in .

Table 1. Participants’ stated career choice at the start of medical school and at interview (FY2).

Main findings

In this section, the overarching process of career decision-making as described by our participants is outlined. Then the complex influence of the medical school programme on that process is set out. A total of 14 recurring CMO configurations were identified () which explain how medical school curricula, placements, role models, peers, career guidance and culture affect the career decisions of students who came to medical school with more or less formed interests, aptitudes and career dreams.

Table 2. Exposure to specialities.

Table 3. Being given an active role and exposure to role models.

The process of career decision-making: testing for fit involving ‘easing in’ or ‘ruling out’

Unlike students of most other university courses, participants arrived at medical school with the big decision already made – they wanted to be doctors. In addition, 16 of 26 also had some idea at that stage, often vague, of their preferred speciality.

Participants described choosing a speciality as ‘testing for fit’ of the career with their own aptitudes and needs. Although a few participants had been testing a strong speciality preference for fit before entering medical school, few did so during the first two years of the course unless triggered by a significant event.

I didn’t really think about the future. I don’t think anyone really does in the first year atMedical School. You kind of just crack on with it and just try and pass each yearN04m

It generally started when more time was spent on clinical placements and many felt they needed to start the process of testing for fit in year 3 or 4 (of five-year courses), at least 3 years before the point in F2 when they apply for speciality training posts.

The concept of testing for fit was described as a more or less active process of appraising the speciality and their aptitude for it. Ruling in and out however were asymmetric processes. Ruling out was generally described as a first impression decision without much testing and was often based on a single negative or boring experience or negative impression from others.

I think I probably more worked on a process of ruling things out rather ruling something in ‘cus [because] I enjoyed pretty much everything I did at Medical School. I just managed to rule some things out as I went along because I couldn’t rule everything in. K17m

By contrast, the process of making a positive choice was usually prolonged. It was initiated by an initial attraction, enjoyment or interest which was sufficient to make the student consider testing it for fit. This initial attraction occurred before medical school for 16 of our 26 participants and for six their preference did not change through testing. All participants however described being attracted to a number of specialities. Crossing the threshold of initial attraction triggered active seeking of further exposure, comparison with previously favoured specialities and multiple tests and checks. A career option could fail any one of these and be ruled out. These tests included features of the career (interest, variety, prestige, lifestyle, requirements) and of how the individual felt in the workplace and their self-efficacy for the activities (are they suited to the role and could they see themselves doing this for the rest of their career?) and continued after leaving medical school.

I’d say that by the end of your Medical School, you’ve spent enough time in clinical scenarios to understand the difference between each speciality and what that might entail in terms of the general shape of training and the type of job you’d do. I don’t know if you have a good understanding of … . things like the workload and how it affects family life and possible earning potential. N03m

The influence of the medical school programme on the process of testing for fit

Our realist evaluation coded text where it was clear that some aspect of the medical school formal or informal curriculum had influenced the process of testing for fit described above. In total, 14 Context-Mechanism-Outcome (CMO) configurations where the same influence recurred multiple times through the data are listed in six main clusters but there is overlap between them:

Exposure to specialities (CMO configurations 1–3) clustered in

Being given an active role (CMO configurations 4 and 5) clustered in

Exposure to role models (CMO configuration 6)

Student choice (CMO configuration 7) see

Medical school culture and the hidden curriculum (CMO configurations 8–11) clustered in

Career guidance (CMO configurations 12–14) clustered in

Table 4. Student choice.

Table 5. Medical school culture, the hidden curriculum.

Table 6. Career guidance.

Most of our CMO configurations confirm the expectations in our initial programme theory but there are four key concepts which explain how these influences work which were helpful additions to our initial programme theory. These were:

Exposure to careers during medical school is incomplete but is enhanced by active participation and by interactions with role models (CMO configurations 1–7).

Student selected components (SSCs), electives were recalled as times when fit was found (CMO configuration 7)

Perspective was biased by various contextual factors (CMO configurations 1–11)

Career advice (CMO configurations 12–14)

Each CMOc is illustrated with one of the supporting quotes. Where the same trigger in different contexts moves medical students in different directions the CMOcs are paired a) and b).

Exposure during medical school is incomplete but is enhanced by active participation and by interactions with role models (CMO configurations 1–7)

When interviewed, participants had progressed to F2 and, in hindsight, saw how partial their view of specialities was during medical school. They were now aware of working hours, responsibilities, patient complaints and task repetitiveness, things they had not always perceived as medical students.

Realistic testing for fit during medical school had been enabled by being given the tasks of a doctor in that speciality. Longer placements (four weeks or longer) made it much easier to test for fit and career decisions were made with more confidence. An element of testing by identification with a role model (‘Could I be him/her?’) was apparent for some. Less commonly, there was a description of a role anti-model (‘If that is what they are like I do not want to be one’).

Student selected components (SSCs), electives were recalled as times when fit was found (CMO configuration 7)

SSCs (placements selected by the student) were often strategically used by participants to test for fit but, even if they chose the SSC or elective for other reasons, some were surprised by the sense of fit. The combination of a student who has chosen a speciality for any reason and a supervisor who gives them special attention and includes them in the team seems to put the speciality in a favourable light and cements the career preference.

Perspective was biased by various contextual factors (CMO configurations 1–11)

Several participants described their view of a career as being ‘rose tinted’ by their preconceptions and the positive experiences described above. Conversely many felt they were biased against a career largely because of peer and medical mentors’ opinions about it, and to a lesser extent by the institutional culture. These negative perceptions were generally not part of the participants’ preconceptions on starting medical school and instead arose from the medical school and its placement providers. Participants were asked about official or unofficial messages they got in medical school about career choice. All those from the home school (K) and some from other schools believed that their school wanted to produce GPs. Some described this as understandable but others as a pressure to be resisted. This belief was underpinned by statements from school staff such as ‘60% of you will become GPs’ but was sometimes inferred from the school’s heavy investment in GP placements or the faculty make-up. Two medical schools were described by their graduates as emphasising hospital careers and claiming that they produced medical leaders in contrast to other schools which produced more GPs. Two schools were described by three participants as promoting individual discovery of the right career which was appreciated by those participants.

As expected, the trade-off between career and life ideals was a consideration mainly after graduation. Some participants, who as medical students had met doctors whose priorities had changed and were struggling with managing family life, reported that they did not necessarily change their own view of the career at the time.

Career advice (CMO configurations 12–14)

There were mixed responses as to what form official career guidance took and how useful it was. The most useful official advice was one-to-one from a career advisor or a personal tutor. Informal guidance was also sought (and given unsought) from multiple seniors on placements and was sometimes found most useful. Listening to the talk of the team was also important for some, with career information gleaned particularly from junior doctors. Doctors’ opinion about their own speciality carried a lot of weight with students and influenced them more than their opinion of the specialities of others which may be expected to be disparaging. If the doctor was unhappy in their own career the negative effect was particularly powerful and can trigger ruling out.

Discussion

Our initial programme theories about what might cause medical students to rule in and rule out career options and the processes by which this might happen were tested by asking junior doctors who were graduates of 12 UK medical schools to recall such times when they were at medical school.

As expected from the literature, their choosing of a career involved deliberative decision-making processes. These calculated decisions, weighing up attributes in themselves and in the potential career would agree with rational choice theories of decision-making such as Subjective Expected Utility theory [Citation22] and Person-Environment-Fit theories of career decision-making [Citation23,Citation24]. We found however that there are also faster, less thought-through decisions being made when ruling out career choices, and that both the deliberative and the less thought-through types of decision-making are triggered by elements in the context. Most participants were not thinking about speciality choice in their first two years at medical school, but once they started encountering specialities on placements they found themselves continually collecting evidence to cautiously explore careers which were attractive on first encounter. We have therefore called this rational choice process ‘easing in’ rather than ‘ruling in’. Easing in is a process which takes time and active information-gathering. Conversely, ruling out is often quick and may use what may appear to be flimsy evidence. One reason for this asymmetry between easing in and ruling out may be that students encounter a number of the 65 medical specialities [Citation25] while in medical school and may feel the need to narrow down the field so that they can focus on a few choices. Rather than making effortful rational decisions, heuristics such as ruling out a speciality which evoked a negative emotional response on first encounter may be adopted to identify unsuitable careers. Brief experiences in medical school may therefore be important because they can trigger ruling out of a career choice which is then unlikely to be considered again. Brief encounters are less important in the easing in process which requires sufficient exposure for aptitude-testing and developing a sense of fit. This may help to explain why placements in which students engage with authentic clinical activity are major attractors to a speciality [Citation13,Citation14] The opinion of others was found to be influential both to easing in and ruling out, but the same asymmetry may operate here with a positive opinion forming part of a body of evidence being gathered in favour of a career option while a negative opinion might be sufficient to trigger a ruling out decision. Pertinent to this, as found in previous studies [Citation17–20], there was a general sense of a hierarchy of careers which was influential and may have discouraged consideration of some career options.

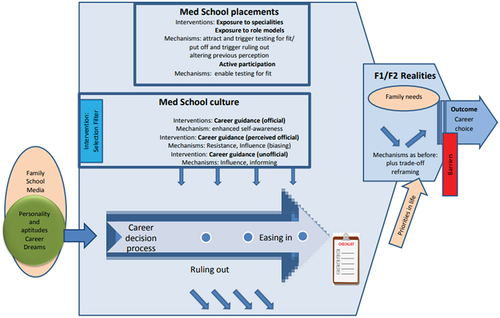

Our final programme theory is that: The process of career decision-making involves the testing for fit of potential careers by either easing in or ruling out. This process is asymmetric with multiple positive experiences needed to ease in but only a few negative experiences needed for a choice to be ruled out. Testing for fit is facilitated by longer and more authentic undergraduate placements, being allocated tasks which are successfully completed, being treated as part of the team and an enthusiastic role model. These may contribute to biased perceptions but may also help students to assess their aptitudes and to get a good enough impression of the speciality to develop a sufficient sense of fit. This oftens seems to happen during SSC placements. Ruling out is also promoted by a negative perception of a speciality in medical school culture and peer pressure.

The parameters of fit which are being tested may change with career progression: a full awareness of the demands of a career or the importance of lifestyle may not become apparent until the young doctor has started work when a previous fit becomes a misfit.

Medical schools affect these processes though curricular design choices for example placement length, the strength of their mandate for student participation in care and the profile given to different role models.

Our final programme theory is illustrated in .

There is a ‘comfortable fit’ or a ‘best fit’ in the perception of the participants in this study but this perception may change either positively or negatively with context over time. The eventual decision after starting work as a doctor may become subject to further constraints such as life priorities and rather than being the idealised best fit is a compromise.

We did not include life priorities in the CMO configurations for this study of medical school influences on career choice since it was clear that most participants only consciously considered these after starting work as a doctor. Its importance should not be underestimated, however, as a large majority of the interviewees cited it as a significant but late driver for career choice. This is an area for further research.

Strengths & Weaknesses: This study has used in-depth interviews to explain career decision-making. The retrospective approach has advantages of identifying the recollections felt to be important to eventual career choice, but some influences may have been forgotten or distorted in recollection. A longitudinal set of interviews might have uncovered other less memorable influences. A rigorous theoretical framework and methods were applied to data analysis. The large data set of 26 interviews samples graduates of 12 UK medical schools who have a range of career preferences. An even larger data set might have discovered other contextual influences. The study is based in the UK medical careers system so findings may not be directly applicable to other contexts. The researchers are reflexive about their own positioning on the medical education and medical careers stage. The group includes hospital doctors and GPs both junior and senior which broadens their perspective as researchers .

Conclusions

Our study suggests that UK medical student thinking about career preference seems to align with Person-Environment-Fit decision theories more than with Subjective Utility Theory. Ruling out a potential career can however be a less thought-through process than rationality-based decision theories would suggest and can be triggered by contextual factors such as medical school culture and fleeting placement encounters. Realist evaluation identifies the contextual factors which change participants’ decisions and thinking and can therefore be used to develop recommendations for programmes wishing to help students to find a good career ‘fit’. Implications for medical school planners are in Box 1.

Box 1. Implications for policy/practice.

(1) Medical student clinical placements are important times for forming career preferences. As this is usually not of the formal curriculum it may need to be recognised as such and thought given to what students are learning. A short exposure to limited aspects of the career may give a distorted perception which could trigger ruling out of that career as an option.

(2) Longer placements (4 weeks or more) with authentic experiences of the career such as performing tasks, being involved in the delivery of patient care and being included in the team permits students to test for fit which is a better way of ruling out or easing in.

(3) Testing for fit ideally includes understanding a career ‘warts and all’, but this needs careful consideration since ruling out of career options can be triggered easily, for example by an experience of boredom or by disparagement of the career especially by a senior who is working in that career themselves.

(4) Career orientated SSCs (Student Selected Components) offer important opportunities to enable testing for fit. Multiple SSCs would expose students to a variety of careers.

(5) Medical schools must be aware that their students perceive them to be giving out messages about careers. These messages come from student peers, students’ perceptions about the emphasis of the curriculum and it steering them towards GP or hospital careers and by faculty comments rather than through official school communications. Students seem to appreciate intentional statements of the school’s desire to encourage them to explore and find their best personal fit. Such messages need to be strong and supported by curricular measures to promote career exploration and test for fit in order to overcome the hidden curriculum.

(6) Career advice is appreciated if one-to-one and at the point of need. Career events are unlikely to provide this but personal tutors, career advisors and informal discussions with seniors on placements are valued as informative. Prompting of discussions of work-life balance may not be welcomed by students who are not currently grappling with that dilemma.

Author contributions

AT conducted some of the interviews, led data analysis and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript as a masters dissertation. JL led the research team which devised the study and were awarded the research grant and revised the manuscript into this paper. All authors contributed to initial programme theory, did coding, discussed modifications of the programme theory and edited drafts of the paper

Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (19.8 KB)Acknowledgments

Dr Helen Thursby who conducted interviews, Dr Stu McBain and Prof Simon Gay who advised on the initial design of the study

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2024.2320459

Additional information

Funding

References

- Goldacre MJ, Turner G, Lambert TW. Variation by medical school in career choices of UK graduates of 1999 and 2000. Med Educ. 2004;38(3):249–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2004.01763.x

- McManus IC, Harborne AC, Horsfall HL, et al. Exploring UK medical school differences: the MedDifs study of selection, teaching, student and F1 perceptions, postgraduate outcomes and fitness to practise. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):1–35. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01572-3

- Mullan F, Chen C, Petterson S, et al. The social mission of medical education: ranking the schools. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(12):804–811). doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-3-201008030-00023

- Schroeder T, Elkheir S, Farrokhyar F, et al. Does exposure to anatomy education in medical school affect surgical residency applications? An analysis of Canadian residency match data. Can J Surg. 2020;63(2):E129–E134. doi: 10.1503/cjs.019218

- Svirko E, Goldacre MJ, Lambert T. Career choices of the United Kingdom medical graduates of 2005, 2008 and 2009: questionnaire surveys. Med Teach. 2013;35(5):365–375. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.746450

- Dall T, West T, Chakrabarti R, et al. The complexities of Physician supply and demand: projections from 2013 to 2025 final report. Assoc Am Med Colls. 2015 Jun. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.13111.57764

- Wass V. By choice, not by chance. 2019.

- Kelly C, Roett MA, McCrory K, et al. A shared aim for student choice of family medicine: an update from adfm and family medicine for America’s health. Anna Family Med. 2018;16(1):90–91. doi: 10.1370/afm.2191

- NHS England and Health Education England. Building the workforce – the new deal for general practice. Royal Coll Gen Pract. 2015;1:1–6.

- Cleland JA, Johnston PW, Anthony M, et al. A survey of factors influencing career preference in new-entrant and exiting medical students from four UK medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1). doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-151

- AAMC. How medical students choose specialties. 2022. https://careersinmedicine.aamc.org/about-cim/how-medical-students-choose-their-specialty

- Yardley S, Littlewood S, Margolis SA, et al. What has changed in the evidence for early experience? Update of a BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2010;32(9):740–746. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.496007

- Nicholson S, Hastings AM, McKinley RK. Influences on students’ career decisions concerning general practice: a focus group study. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(651):e768–e775. doi: 10.3399/bjgp16X687049

- Passi V, Johnson S, Peile E, et al. Doctor role modelling in medical education: BEME Guide No. 27. Med Teach. 2013;35(9):e1422–36. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.806982

- Alberti H, Randles HL, Harding A, et al. Exposure of undergraduates to authentic GP teaching and subsequent entry to GP training: a quantitative study of UK medical schools. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67(657):e248–e252. doi: 10.3399/bjgp17X689881

- Clark TR, Freedman SB, Croft AJ, et al. Medical graduates becoming rural doctors: rural background versus extended rural placement. Med J Aust. 2013;199(11):779–782. doi: 10.5694/mja13.10036

- Ajaz A, David R, Brown D, et al. BASH: badmouthing, attitudes and stigmatisation in healthcare as experienced by medical students. BJPsych Bull. 2016;40(2):97–102. doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.115.053140

- Barber S, Brettell R, Perera-Salazar R, et al. UK medical students’ attitudes towards their future careers and general practice: a cross-sectional survey and qualitative analysis of an oxford cohort. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1197-z

- Merrett A, Jones D, Sein K, et al. Attitudes of newly qualified doctors towards a career in general practice: a qualitative focus group study. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67(657):e253–e259. doi: 10.3399/bjgp17X690221

- Brooks JV. Hostility during training: historical roots of primary care disparagement. Anna Family Med. 2016;14(5):446–452. doi: 10.1370/afm.1971

- Erikson CE, Danish S, Jones KC, et al. The role of medical school culture in primary care career choice. Acad Med. 2013;88(12):1919–1926. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000038

- Reed VA, Jernstedt GC, Reber ES. Understanding and improving medical student specialty choice: a synthesis of the literature using decision theory as a referent. Teach Learn Med. 2001;13(2):117–129. doi: 10.1207/S15328015TLM1302_7

- Holland JL. Making vocational choices: a theory of vocational personalities and work environments. Englewood Cliff, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1985.

- Parsons F. Choosing a vocation. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 1909.

- BMA. Sci 59. n.d. [cited 2021 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/career-progression/training/specialty-explorer

- Querido SJ, Vergouw D, Wigersma L, et al. Dynamics of career choice among students in undergraduate medical courses. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 33. Med Teach. 2016;38(1):18–29. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1074990

- Law B. Community interaction: a ‘mid-range’ focus for theories of career development in young adults. Br J Guid Counselling. 1981;9(2):142–158. doi: 10.1080/03069888108258210

- Goldsmith RE. Rational choice and bounded rationality. In: Emilien G, Weitkunat R, and Lüdicke F, editors. Consumer perception of product risks and benefits. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 233–252. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-50530-5_13

- Yang Y, Li J, Wu X, et al. Factors influencing subspecialty choice among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):1–12. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022097

- Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation. Sage; 1997. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/

- Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, et al. Realist methods in medical education research: what are they and what can they contribute? Med Educ. 2012;46(1):89–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04045.x

- Merton R. On sociological theories of the middle range. In: Merton RK, editor. On theoretical sociology: five essays, old and new. The Free Press; 1967. p. 39–72. https://www.biomedcentral.com/about

- Wong G, Westhorp G, Manzano A, et al. RAMESES II reporting standards for realist evaluations. BMC Med. 2016;14(1). doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0643-1

- General Medical Council. (2022). Guidance on undergraduate clinical placements. https://www.gmc-uk.org/education/standards-guidance-and-curricula/guidance/undergraduate-clinical-placements/guidance-on-undergraduate-clinical-placements

- Yardley S, Teunissen PW, Dornan T. Experiential learning: AMEE Guide No. 63. Med Teach. 2012;34(2):e102–15. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.650741

- Lefroy J, Yardley S, Kinston R, et al. Qualitative research using realist evaluation to explain preparedness for doctors’ memorable ‘firsts’. Med Educ. 2017;51(10):1037–1048. doi: 10.1111/medu.13370

- Yardley S, Kinston R, Lefroy J, et al. ‘What do we do, doctor?’ transitions of identity and responsibility: a narrative analysis. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2020;25(4):825–843. doi: 10.1007/s10459-020-09959-w

- Cleland J, Prescott G, Walker K, et al. Are there differences between those doctors who apply for a training post in foundation year 2 and those who take time out of the training pathway? A UK multicohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11):1–12. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032021

- Hollis AC, Streeter J, Hamel CV, et al. The new cultural norm: reasons why UK foundation doctors are choosing not to go straight into speciality training. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(282):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02157-7