ABSTRACT

Shifting to a competency-based (CBME) and not time-bound curricular structure is challenging in the undergraduate medical education (UME) setting for a number of reasons. There are few examples of broad scale CBME-driven interventions that make the UME program less time-bound. However, given the range of student ability and varying speed of acquisition of competencies, this is an area in need of focus. This paper describes a model that uses the macro structure of a UME program to make UME curricula less time-bound, and driven more by student competency acquisition and individual student goals. The 3 + 1 curricular model was derived from the mission of the school, and includes a 3-year core curriculum that all students complete and an individualized phase. Students have an 18 month individualized educational program that meets their developmental needs and their educational and professional goals. This is achieved through a highly structured advising system, including the creation of an Individualized Learning Plan, driven by specific goals and targeted Entrustable Professional Activities (EPA). Students who struggle in achieving core competencies can use individualized time to support competency development and EPA acquisition. For students who have mastered core competencies, options include obtaining a masters degree, clinical immersion, research, and community-based experiences. Students can also graduate after the 3-year core curriculum, and enter residency one year early. Structural approaches such as this may contribute to the norming of the developmental nature of medical education, and can advance culture and systems that support CBME implementation at the UME level.

Introduction/problem

Shifting to a competency-based and not time-bound curricular structure is challenging within undergraduate medical education (UME) given the scale of class size and fixed aspects of UME, such as the timing and nature of the residency selection process. A few schools have created small-scale programs for students applying in selected fields to accelerate their UME curriculum and enter residency earlier [Citation1–3]. Even fewer are trying to create school-wide infrastructure to flex the length of courses and clerkships based on student achievement of competency [Citation4,Citation5]. Few, if any, schools have created non time-bound UME training on a broad scale. However, given the range of student ability and varying rate of acquisition of competencies, this is an area in need of focus, both to support students who need more time to achieve competencies and those who achieve competencies quickly and can therefore progress farther during medical school [Citation6]. The structure of our educational program aims to make UME curricula less time-bound, and driven more by student competency acquisition and individual goals.

Approach/intervention

As a new medical school, we embraced the opportunity to build a mission-driven school [Citation7]. This informed the what (content), the how (instructional methods), and the structure of the educational program and school. During initial development, we identified key societal problems we aimed to address. This included challenges the United States faces in health outcomes and health equity, as well as educational and healthcare workforce issues. Given the cost of medical education and student debt-burden, particularly on students from backgrounds underrepresented in medicine, we focused on the macro-structure of our educational program. Additionally, we set a high target-level competency for our learners in clinical reasoning and clinical skills. We noted that students acquire competency at developmentally different rates. Many are able and driven to achieve more in four years than simply core content, while other students need more than the allotted time to achieve required competencies.

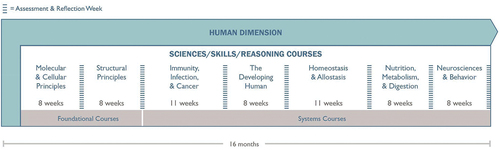

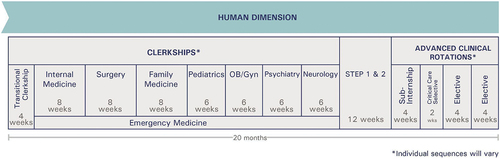

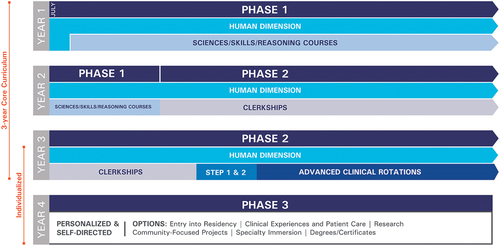

These considerations led to the 3 + 1 macro-structure of our curriculum, including a generally 3 year core-curriculum that all students complete (Phases 1 and 2) and an individualized Phase 3, as seen in . Combined with the individualized final 6 months of Phase 2, students have an 18 month individualized educational program. These are developed through a highly structured advising system and the creation of an Individualized Learning Plan (ILP) for each student. Students work with their advisors and faculty mentors from the beginning of the UME curriculum to build a program that meets their educational and professional goals and their developmental needs. Each student’s ILP is driven by specific goals and targeted Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) [Citation8] from our 18 EPAs (13 from the Core EPA Pilot and 5 developed internally). Students who struggle in achieving competencies within Phases 1 and/or 2 can use Phase 3 time at the relevant time for curricular experiences to support competency development and EPA acquisition. This includes additional time to complete courses/clerkships, clinical skills intensives to remediate deficiencies, and time to build metacognitive academic and clinical skills.

Figure 1. Overall HMSOM curriculum.

For students who have mastered core competencies, Phase 3 options include masters degrees, clinical immersion, intensive research, and community-based projects. Students can also graduate after the 3-year core curriculum, and enter residency one year early, generally within the Hackensack Meridian Health System. Likewise, if a student needs a significant amount of additional time to achieve their core competencies, they can extend their enrollment past 4 years at minimal cost. provides descriptions of Phase 3 educational activities.

Table 1. Examples of educational activities within each category of phase 3 (individualized) portion of the Hackensack Meridian School of Medicine curriculum.

The scale of UME, as compared to Graduate Medical Education, makes the separation of competency-acquisition from time challenging. Medical school class sizes of 100–200 are orders of magnitude larger than a typical residency class. Our approach enables us to individualize the UME program for each student in our class of 165, releasing us from the traditional time-bound and fixed nature of UME. In addition to providing needed time and experiences to students who have not yet mastered core competencies, this also enables us to support students who are able to achieve more within their 4 years of medical school. They can graduate with 2 degrees, complete an intensive 12–18 month project, or accelerate their graduation and enter residency after 3 years.

Outcomes

To date, two cohorts have completed all Phases of the curriculum. Each student created and completed their individualized plan. These plans included various combinations of types of educational activities; students are able to participate in more than one activity at a time. For example, a student can complete a research project that they work on part time for 10 months, while during that time they complete clinical rotations. In the most recent cohort, 32% of students graduated after 3 years (range of all classes to date 18–32%). For students who stayed for the fourth year, of the total amount of curricular activities completed, 55.3% were clinical, 22.4% were research, 8.5% were graduate programs, 4.9% were foundational competency development, and 8.9% were medical education, Health Systems Science, community, and other. shows examples of student’s schedules from different curricular paths.

Table 2. Individualization Phase. This includes the final 6 months of Phase 2 and all of Phase 3. Shown here are examples of student schedules in different types of individualized programs. The specialty the student is going into is shown in parentheses. Note that the length of rotations varies; therefore, the table only shows the components and sequence of the curricular activities. For longitudinal experiences students are able to combine two different activities, shown here within a block separated by a slash.

Discussion: next steps and lessons learned

As our class size reaches steady state, we continue to build out and scale up processes for advising and ILP plan review and approval. This requires a robust team of advisors, faculty, and staff, and integrated systems. Data systems and reporting are critical to the success of the program.

A percentage of the class utilizes some portion of Phase 3 to achieve core competencies of Phase 1 and/or 2. This has necessitated the development of significant curricular structures to support students on alternate schedules to ensure they are identified, supported, and provided with feedback and experiences that enable their success.

A further challenge relates to the conflicting goals that UME educators strive for: (1) building competent physicians using a mastery approach including the sharing and integration of feedback and (2) differentiating students for residency application. This conflict will continue to obstruct the full implementation of CBME within UME. However, our structural approach may contribute to the norming of the developmental nature of medical education, and the fact that students will achieve goals (both core required and advanced) at different rates. The medical education community needs to build the systems and culture to support this important effort.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank the faculty, staff, and students of the Hackensack Meridian School of Medicine.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Consortium of accelerated medical pathway programs. consortium of accelerated medical pathway programs. [accessed 2023 Oct 18]. Available from: https://www.acceleratedmdpathways.org

- Cangiarella J, Cohen E, Rivera R, et al. Evolution of an accelerated 3-year pathway to the MD degree: the experience of New York University Grossman School of Medicine. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2020;95(4):534–5. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003013

- Cangiarella J, Fancher T, Jones B, et al. Three-year MD programs: perspectives from the consortium of accelerated medical pathway programs (CAMPP). Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2017;92(4):483–490. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001465

- Andrews JS, Bale JF, Soep JB, et al. Education in pediatrics across the continuum (EPAC): first steps toward realizing the dream of competency-based education. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2018;93(3):414–420. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002020

- Lomis KD, Mejicano GC, Caverzagie KJ, et al. The critical role of infrastructure and organizational culture in implementing competency-based education and individualized pathways in undergraduate medical education. Med Teach. 2021;43(sup2):S7–S16. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2021.1924364

- Carraccio C, Lentz A, Schumacher DJ. “Dismantling fixed time, variable outcome education: abandoning ‘ready or not, here they come’ is overdue”. Perspect Med Educ. 2023;12(1):68–75. doi: 10.5334/pme.10

- Hoffman M, Metzger K, Martinez O, et al. Hackensack Meridian School of Medicine at Seton hall university. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2020;95(9S):S313–S317. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003462

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Core entrustable professional activities for entering residency. 2017. [accessed 2020 July 28]. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/system/files/c/2/484778-epa13toolkit.pdf