ABSTRACT

In clinical clerkship (CC), medical students can practice evidence-based medicine (EBM) with their assigned patients. Although CC can be a valuable opportunity for EBM education, the impact of EBM training, including long-term behavioral changes, remains unclear. One hundred and nine fourth- and fifth-year medical students undergoing CC at a medical school in Japan attended a workplace-based learning program for EBM during CC (WB-EBM), which included the practice of the five steps of EBM. The program’s effect on the students’ attitudes toward EBM in CC was assessed through questionnaires. A total of 88 medical students participated in the program. Responses to the questionnaire indicated high satisfaction with the WB-EBM program. The most common theme in students’ clinical problems with their assigned patients was the choice of treatment, followed by its effect. Based on the responses in the post-survey for the long-term effects of the program, the frequency of problem formulation and article reading tended to increase in the ‘within six months’ group comprising 18 students who participated in the WB-EBM program, compared with the control group comprising 34 students who did not. Additionally, the ability to self-assess problem formulation was significantly higher, compared with the control group. However, among 52 students who participated in the WB-EBM program more than six months later, EBM-related behavioral habits in CC and self-assessments of the five steps of EBM were not significantly different from those in the control group. The WB-EBM program was acceptable for medical students in CC. It motivated them to formulate clinical questions and enhanced their critical thinking. Moreover, the WB-EBM program can improve habits and self-evaluations about EBM. However, as its effects may not last more than six months, it may need to be repeated across departments throughout CC to change behavior in EBM practice.

Introduction

In clinical practice, evidence-based medicine (EBM) is defined as medicine that uses the best available scientific information to guide appropriate clinical decisions. It is important for resolving clinical questions and promoting patient-centered care [Citation1,Citation2]. The practice of EBM is recommended in five steps: 1) problem formulation, 2) information searching, 3) critical examination, 4) application to patients, and 5) reflection. In recent years, the rapid increase in the amount of available medical information has been a challenge for medical education [Citation3]. For example, erroneous medical information regarding coronavirus disease 2019 was disseminated, causing confusion even among medical professionals [Citation4]. The practice of EBM has thus become more complex and involves lifelong learning.

Practicing EBM has become a core competency in the curricula of medical schools globally and is taught prior to and throughout clinical practice. In the UK, EBM serves as an introductory program before the start of the formal curriculum [Citation5]. In a survey of EBM education for medical students in the US and Canada, almost all medical schools reported that EBM education was included in the regular curriculum [Citation6]. Similar to other countries, the Model Core Curriculum for Medical Education in Japan (MCCMEJ), revised in 2016 by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, included EBM education as the basis of medical treatment [Citation7]. Although a combination of education methods, such as lectures, e-learning, group discussions, journal clubs, and the use of technology has been useful in improving EBM knowledge and skills [Citation6], an effective teaching methodology for EBM has yet to be established [Citation8,Citation9]. The policies of each educational institution and their educational practices have been left to the individual educators, leading to insufficient sharing and accumulation of model practices.

In clinical clerkships (CC), medical students participate in actual medical care as student doctors in medical professionals’ teams and can raise clinical questions regarding their assigned patients. Clinically integrated EBM teaching is more effective than classroom teaching [Citation10] and can best be taught during CC; however, it is not optimally practiced in clinical settings owing to multiple barriers, including difficulties in applying EBM skills learned in the classroom to clinical practice [Citation11]. Apart from the setting where it is applied, the effect on students will depend on the skillfulness and eagerness of the faculty in training them [Citation12]. In addition, education for EBM is not optimally practiced in clinical settings owing to multiple barriers, including difficulties in transferring EBM skills learned in the classroom to clinical practice [Citation11].

In our lecture for clerkship students in respiratory medicine held in 2019 [Citation13], we showed that lectures on literature search during CC, where medical students needed to solve clinical questions, could be effective in improving literature search literacy. However, our previous report only focused on literature search during CC, while other elements of the five steps of EBM were not adequately addressed. Considering the process of resolving clinical questions in CC, learning all five steps of EBM is encouraged [Citation14]. Reports on EBM education being integrated into CC [Citation15–18], have mainly focused on EBM training based on fictitious clinical scenarios. Therefore, the long-term effectiveness of EBM education needs to be verified [Citation19].

This study developed a workplace-based learning program for EBM during CC (WB-EBM program) that integrated the five steps of EBM in CC based on the students’ assigned patients. We then evaluated the effect of our program on students’ attitudes toward EBM in CC.

Methods

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chiba University (approval no. 4106). The study database was anonymized. Informed consent was procured from the participants prior to their participation in the survey that was documented on the Web. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Study design

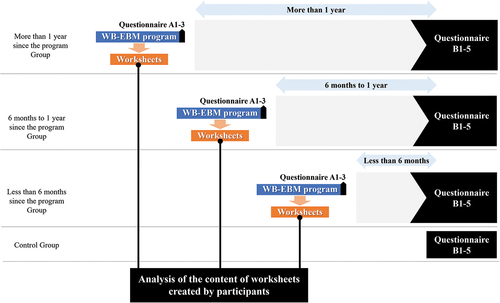

This was a descriptive, interventional study comparing two groups without randomization (). The effectiveness of the WB-EBM program was evaluated through worksheets created by the participants in the WB-EBM program and questionnaires administered to participants and non-participants. A post-questionnaire was also administered to evaluate the long-term effects of the program. The responses were compared between three groups based on the length of time since they had participated in the program, as well as with a control group that had not participated the program.

Setting

Pre-clinical clerkship

Medical schools in Japan offer a six-year curriculum, of which two years are generally spent in CCs [Citation15]. In Chiba University, a lecture on literature search is given in the first year as an instruction of EBM education. From the first to third year, students are assigned to laboratories to conduct research activities through a scholarship program, through which some students begin reading English medical articles. However, the educational method applied to the students is not standardized and differs depending on the instructor. Additionally, the content of the curriculum mainly focuses on basic research and does not realistically reflect clinical practice.

Clerkship

From December of the fourth year to October of the sixth year, clerkship students are rotated from one department to another every four weeks for 72 weeks in the university hospital. In the CC of the Department of Respiratory Medicine, groups of seven to eight medical students underwent a four-week training program as members of a medical team of doctors and residents. All medical students conducted daily physical examinations for two to four patients assigned to them during this four-week period. In addition to writing daily medical records, the students were required to write two case summaries within the four-week CC and include at least one reference in each summary.

Participants

Chiba University has approximately 120 medical students in each academic year. The number of participants in this study was based on realistic possibility without calculating a sample size. The sample was recruited based on 145 students who underwent CC from May 2021 to July 2022. This study included two grades of students: those who started CC in December 2020 and those who started CC in 2021. Students were able to choose CC in either the Respiratory Medicine or Thoracic Surgery departments. During the study period, 109 students underwent CC in the Department of Respiratory Medicine and attended the WB-EBM program. The remaining 36 students underwent CC for Thoracic Surgery, acting as the control group.

To evaluate the long-term effects of the program, the students who participated answered a post-questionnaire more than three months after the WB-EBM program. In addition, the control group who underwent CC in the Department of Thoracic Surgery and had not participated in the program also answered the same questionnaire.

WB-EBM program

This study evaluated the effects of the WB-EBM program on medical students in CC. The program consisted of a 60-min lecture and a 120-min group discussion delivered by one of the authors of this paper (GS, HK) during the first and third week of the CC, respectively. summarizes the schedule and contents of the WB-EBM program.

Table 1. Time course and contents of the WB-EBM program.

First session

The attending doctor (GS) conducted a lecture using PowerPoint™. The first session was divided into three sections: 1. Overview of EBM (10 min); 2. Introduction to making the population, intervention/exposure, comparison, outcome (PICO/PECO) (15 min); and 3. Introduction to literature search and practice (35 min). In the first section, the definition of EBM [Citation21] was explained by presenting the history of the treatment of scurvy and the points where progress was not made because past medicine ignored evidence. In addition, the hierarchy of evidence [Citation22] and its limitations, and the impact factor and its limitations were explained. The second section explained the definitions of background and foreground questions, the method of formulating clinical questions following PICO/PECO framework, the usefulness and limitations of secondary sources, the importance of primary sources, and how to examine primary sources. The third section described literature search engines and literature search methods. Based on the above, a simulated case of a patient with severe asthma was presented to the students, and each student practiced searching for additional treatment options.

After the lecture, the medical students formulated clinical questions following the PICO/PECO framework based on their own cases. Based on their clinical question, they conducted a literature search, read an article, and examined the applicability of the question to their cases. They then summarized the activities on a designated worksheet (Supplementary Figure S1), which was submitted at the end of the third week of CC. The supervising doctor (HK, GS, KT) checked the worksheets and discussed them with the students during the small group meetings in the fourth week.

The worksheets in the WB-EBM program included overviews of the case, foreground question, process and methodology, details of the article (title, source, and authors), an overview of the abstract of the article, discussion by students, the degree of the question solution, and unclear points and other comments. Degree of resolution of the student’s foreground question was scored by self-assessment on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Unresolved) to 5 (Fully resolved).

Second session

The attending doctor (GS, KT) conducted the second session, which was divided into two sections: 1. Practice critical examination (20 min), 2. Presentation of worksheets and critical examination by peer students (100 min). In the first section, the original article ‘Phase II Study on MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy for PTSD Patients’ published in The Lancet Psychiatry [Citation20] was introduced to the students. In the Japanese Internet news article, the news article was incorrectly described: ‘The Lancet also published a study on MDMA for PTSD patients, and MDMA will soon become a PTSD treatment drug.’ Students critically examined the article in terms of PICO/PECO, the difference between surrogate and true endpoints, and the phases according to the clinical study. They then had a group discussion on the issues in the news article. Throughout this process, students practiced identifying what was wrong with the citation, its correct interpretation, and the steps of the clinical study. In the second section, peer students discussed the articles that each student had researched, which involved the following: 1) introduction (1 min), 2) reading of the abstract by each participant (2 min), 3) peer review and discussion of the article (2 min), and 4) discussion by all participants (3 min). Up to this point, the students who had examined the paper in question moderated the discussion and examined how the paper could be interpreted by PICO/PECO. The attending doctor (GS, KT) allowed three minutes for commentary on each article.

Data collection

Evaluation of the WB-EBM program

To evaluate the effect of the WB-EBM program on the students, quantitative data were obtained from their responses to the questionnaire (): (A1) What is your level of satisfaction with the WB-EBM program? (A2) Did it motivate you to do more literature searches? (A3) Did it make you think about the correctness or incorrectness of medical information? The questions were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 [Extremely poor (A1); Extremely disagree (A2 and A3)] to 5 [Extremely good (A1); Extremely agree (A2 and A3)].

Table 2. Questionnaire items before and after the WB-EBM program.

Assessment of the worksheets

For the worksheets completed by the students through the WB-EBM program, we assessed the theme of the clinical question formulated by the students, literature search methods, type and research design of the searched literature, and year of publication. The research designs of the retrieved literature were categorized according to those generally used in the guidelines: 1) evidence from a systematic review or meta-analysis of all relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 2) evidence from well-designed RCTs, 3) evidence from well-designed controlled trials without randomization, 4) evidence from well-designed case-control and cohort studies, 5) evidence from systematic reviews of descriptive and qualitative studies, 6) evidence from single descriptive or qualitative studies, and 7) evidence from the opinion of authorities and/or reports of expert committees [Citation22,Citation23]. Degree of resolution of the student’s foreground question was scored by self-assessment on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Unresolved) to 5 (Fully resolved).

Evaluation of the long-term effect of the WB-EBM program

A survey was administered to all participants in November 2022. The participants included students who had attended a WB-EBM program for less than six months, six months to one year, and more than one year. The students were divided into three groups depending on the duration of their WB-EBM program: within six months, six months to one year, and more than one year.

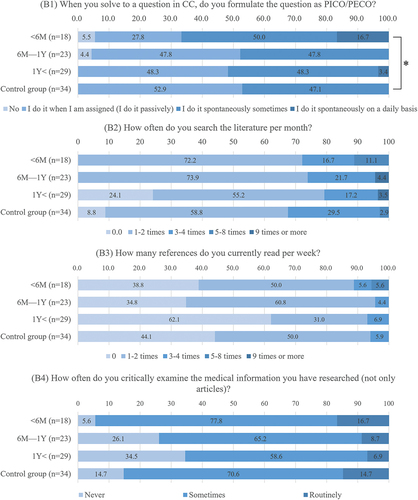

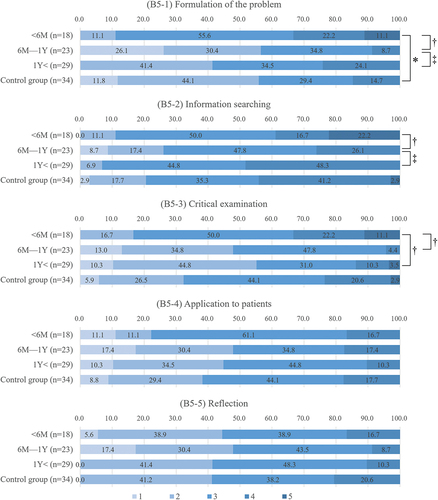

The questionnaire included the following items regarding EBM practice in CC as shown in : (B1) When you have a clinical question during CC, do you formulate the question as PICO/PECO? (‘No,’ ‘I do it when I am assigned [passively],’ ‘I do it spontaneously sometimes,’ ‘I do it spontaneously on a daily basis’); (B2) How often do you search the literature per month? (‘0,’ ‘1–2 times,’ ‘3–4 times,’ ‘5–8 times,’ ‘9 times or more’); (B3) How many references do you currently read per week? (‘0,’ ‘1–2 times,’ ‘3–4 times,’ ‘5–8 times,’ ‘9 times or more’); (B4) How often do you critically examine the medical information you have researched (not only articles)? (‘Never,’ ‘Sometimes,’ or ‘Routinely’); and (B5) What is your self-assessment of your competency in EBM? Question (B5) was divided into the following five items: (B5–1) problem formulation, (B5–2) information gathering, (B5–3) critical examination, (B5–4) application to patients, and (B5–5) reflection. A rubric was presented for the rating, as shown in . The questionnaire items and the rubric were created by an author (GS) through the consensus of two medical education specialists (HK and SI).

Statistical analysis

The quantitative data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise indicated. The continuous variables were compared between the groups using the Mann – Whitney U test and the proportions of categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s chi-square test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS for Windows, version 29.0 (IBM Company, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

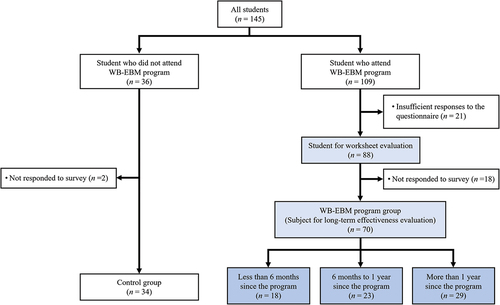

A total of 109 medical students participated in the WB-EBM program during the study period. After excluding 21 students who provided insufficient responses to the questionnaire and 11 students with missing report data, the final sample included 88 students (64 men and 24 women) for report evaluation. shows a flow diagram with the reasons for excluding participants from the analysis.

Figure 2. Flow diagram showing the reasons for participant exclusion from the analysis.

Evaluation of the education program

Seventy-nine students (89.8%) showed a high satisfaction level (scores 4 and 5) with the WB-EBM program (4.5 ± 0.7). The program highly motivated them to conduct more literature searches and consider the correctness or incorrectness of medical information (4.6 ± 0.6 and 4.6 ± 0.5, respectively).

Assessment of the worksheets

summarizes the worksheets of the 88 students in the WB-EBM program. Regarding the theme in PICO/PECO formulated by the students, the choice (n = 27, 30.7%) and effect of treatment (n = 27, 30.7%) were the most common. Regarding the methods of literature search, keyword search by PubMed was the most common (n = 50, 56.8%), followed by requotation from guidelines on the disease of student-assigned patients (n = 24, 27.2%). Regarding the year of publication, literature published in 2011 (ten years ago from this study period) onwards accounted for 76.1% of the total (2011–2020: n = 52, 59.1%; 2021–, n = 15, 17.0%). However, a few students chose literature published before 2000 (1981–1990: n = 1, 1.1%; 1991–2000: n = 4, 4.5%). Regarding the degree of resolution of their foreground question in the self-assessment, 71.0% of the students agreed that a high degree of resolution had been achieved (5 [fully resolved]: n = 8, 10.2%; 4: n = 49, 55.7%).

Table 3. A rubric for competence in EBM.

Evaluation of the long-term effect of the WB-EBM program

Among the 88 students, 70 students (79.5%; 56 men and 14 women) responded to a post-survey for the long-term effect of the program (WB-EBM program group). Thirty-four students who did not participate in the program owing to their assignment to CC in the Department of Thoracic Surgery (25 men and 9 women) also responded to the survey (control group). summarizes the responses of the WB-EBM program and control groups.

Table 4. Summary of worksheets created by students through the WB-EBM program (n = 88).

Table 5. Comparison of long-term effect of the WB-EBM program between the WB-EBM program group and control group (n = 104).

There were no significant differences in the responses of all students in the WB-EBM program and control groups regarding the formulation of the question as PICO/PECO (p = 0.330), frequency of literature search in a month (p = 0.664), number of articles read per week (p = 0.892), and the habit of critically examining the literature (p = 0.469). There was also no significant difference between the two groups in their self-evaluation of the five steps of EBM: problem formulation (WB-EBM program group, 2.8 ± 1.0 vs control group, 2.5 ± 0.9, p = 0.121), information gathering (3.3 ± 0.9 vs control group, 3.2 ± 0.9, p = 0.979), critical examination (2.7 ± 0.9 vs 2.6 ± 0.9, p = 0.255), application to patients (2.7 ± 0.9 vs 2.6 ± 0.9, p = 0.666), and reflection (2.6 ± 0.8 vs 2.8 ± 0.8, p = 0.338).

show a comparison of the long-term effect of the program on attitudes and behaviors of EBM practice and self-assessment of competency in EBM of the program between the WB-EBM and control groups. The frequency of problem formulation was significantly higher in the within-six months group compared with those in the control group (p = 0.026). The self-assessments of the within-six months group’s problem formulation abilities were also significantly higher than those in the control group. However, the EBM-related behavioral habits in CC of the 23 students from the six months to one year group and the 29 students from the one year later group and their self-assessments of the five steps of EBM, were not significantly different from those of the control group. The self-evaluations of the six months to one year group on problem formulation and critical examination were significantly lower than that of the within-six months group (2.3 ± 1.0 vs 3.3 ± 0.8, p = 0.001; 3.3 ± 0.9 vs 2.5 ± 0.9, p = 0.005, respectively). The self-evaluations of the six months to one year group on their problem formulation (p = 0.043) and information gathering (p = 0.037) were significantly lower than that of the more than one year group (2.3 ± 1.0 vs 2.8 ± 0.8, p = 0.043; 2.9 ± 0.9 vs 3.4 ± 0.6, p = 0.037, respectively).

Figure 3. Comparison of the long-term effect of the program for attitudes and behaviors of EBM practice between the WB-EBM and control groups (n = 104).

Figure 4. Comparison of the long-term effect of the program for self-assessment of competency in EBM of the program between the WB-EBM and control groups.

Twenty-three students (32.9%) expressed a favorable opinion of the WB-EBM program. In particular, six students (8.6%) stated that participation in the program was useful in their CC. Some of the students’ comments from the post-survey include: ‘Having learned the know-how of literature search in CC of Respiratory Medicine, I am no longer afraid of searching literature in English and can find what I want on a daily basis,’ ‘I was able to apply the mindset taught to literature search at the CC after Respiratory Medicine,’ and ‘After participating in the WB-EBM program, I was able to remember to critically examine articles when reading them during my CC in other departments.’ In addition, five students (7.1%) identified problems and areas for improvement, such as the length of class time and inadequate materials.

Discussion

This study evaluated the effectiveness of the WB-EBM program during CC. The three main findings are as follows: First, the WB-EBM program was acceptable for the medical students in CC, and it presented them with an opportunity to learn EBM in a clinical setting. In particular, the WB-EBM program can improve the ability of formulating their clinical questions. Second, medical students’ literature searches at CC were often based on requotations from secondary literature, such as guidelines. Furthermore, there was insufficient interest in the year of publication of the literature they searched. Third, while students perceived the WB-EBM program as a good opportunity to learn EBM, the long-term impact of EBM practice in CC was limited.

Although there is no established method for EBM education [Citation8], a combination of lectures, e-learning, group discussions, journal club, and technology are considered useful for improving EBM knowledge and skills [Citation24]. Furthermore, peer teaching has been effective in EBM education [Citation25]. In this study, in addition to the lecture on literature search conducted in our previous report [Citation13], the program included activities that trained medical students to formulate clinical questions, critically review the literature examined, and reflect on their assigned patients. Peer reviews were also conducted, in which students shared the literature they examined and identified areas for improvement in their critical-thinking ability. Peer review may promote metacognition through self-assessment and reflection; this would enable students to check on each other’s learning status and share information on searching for better literature that can be applied to clinical problems.

The WB-EBM program allowed students to practice formulating clinical questions, searching the literature, and determining whether the information retrieved can be applied to clinical practice. Consequently, they were able to formulate their own clinical questions related to their assigned patients and conduct EBM to resolve them, as seen in the students’ responses in the worksheets (5 [fully resolved]: n = 8 [9.2%] and 4: n = 49 [56.3%]). Some students also stated that the WB-EBM program was useful in subsequent CC.

There has been limited research on how medical students conduct literature searches during their CC. In this study, about 71.6% (63/88) of the students’ clinical questions were related to the selection, efficacy, and side effects of the treatment of their assigned patients. Before their CC, the students often used textbooks, which may contain out-of-date information, especially given the remarkable speed of treatment development in recent years [Citation26]. Therefore, textbooks must only be used as a backbone to understanding a disease, and should always be augmented by journals and other aids to stay abreast of medical advancement [Citation26].

While PubMed was the most commonly used search method in the present study, Gruppen et al. [Citation27] reported that a single and brief training session could have a marked beneficial effect on the quality of subsequent and short-term EBM literature searching performance outcomes. In the report, the most common search errors were a lack of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) explosion, missing MeSH terms, lack of appropriate limits, failure to search for the best evidence, and inappropriate combination of all search concepts [Citation27]. Requotation from guidelines on the disease of student-assigned patients was the second most used method (30.7%; 24/88). This may be because of the availability of Japanese-language guidelines, and the fact that they contain content consistent with clinical questions about treatment selection and efficacy.

Sánchez-Mendiola et al. [Citation18] reported that usage of the Cochrane Library and secondary journals increased after an educational intervention on EBM for CC students. Education in reading English language articles can be a barrier for EBM education in non-English speaking countries [Citation11]. Therefore, guidelines in Japanese have been an important means of accessing the information sought by students. In fact, the Japanese-language guidelines for lung cancer and pulmonary hypertension, which were frequently cited by the students in this study, were available free of charge, and may have been an accessible source of information. While guidelines can certainly be useful, their contents can quickly become outdated [Citation28,Citation29]. In fact, 22.7% (20/88) of the references examined by the students were older than 2010. Therefore, instructing students to use more recent references as much as possible is crucial. In addition, experience in literature searches without using guidelines is also necessary because there are many relatively rare diseases for which guidelines do not exist.

More than six months after the WB-EBM program, there was no significant difference in the behavior of students who did not participate in the program, as well as in their self-evaluation of EBM, such as literature search and number of articles read. Furthermore, their self-evaluations of problem formulation, literature search, and critical examination tended to decrease over time. Since the WB-EBM program was conducted sequentially during the 72-week CC in the first year of the program, it was only done in one department. Thereafter, it was up to the students whether they would continue their EBM practice. Therefore, while the WB-EBM program could lead to long-term behavioral changes in EBM practice, its effects may only show limited continuity. The previous report found that medical students’ literature search literacy may not improve after a single educational opportunity [Citation15]. Furthermore, EBM education needs to move away from an isolated and/or transient approach [Citation30], and toward a more longitudinal one throughout medical education [Citation12]. Adopting a scaffolded curriculum integration approach during the preclinical years can increase – or at least maintain – students’ ability to apply EBM concepts to patient care [Citation30]. Further improvements are needed to improve long-term effectiveness.

A curriculum that provides students with opportunities to practice EBM throughout the CC period should be considered. A student who had attended the WB-EBM program commented in the post-survey, ‘I learned a lot, but I thought it would be better if there were similar workshops in other departments so that we could better practice EBM according to our respective departments.’ Another student commented, ‘I felt that the lecture during the CC was more useful than the lecture given in the classroom before the CC, because I could understand the lecture more deeply.’ In the future, students will practice the lecture component of the WB-EBM program immediately prior to the CC period. Following this, each department will repeat group discussions on the formulation of clinical problems, literature searches, and critical reviews of the literature in accordance with the problems in their respective fields. This continuous approach may influence medical students’ EBM practice. Additionally, tracking the changes in learning effectiveness for the EBM habits of the same population over time should also be considered.

The present study has some limitations. First, as it was carried out at just one medical school in Japan, its effects on participants and their comments are subject to cultural bias. Second, regarding research design, this single-site study only sampled a few participants in an uncontrolled environment and relied partly on students’ self-assessments for data collection. Third, the study was only conducted in a single department. The questionnaire was administered when medical students doing CC were rotated to the Department of Respiratory Medicine. Therefore, what they learned from the previous departments may have influenced their responses. Fourth, the questionnaire items and the rubric in this study were not evaluated for validity and reliability. In the future, the WB-EBM program and assessment of EBM competencies must be evaluated using a validated consensus-based test, such as the Fresno Test [Citation31] and the Berlin Questionnaire [Citation32]. Fifth, the time taken for the self-study of EBM before and during CC can differ for each student; however, this was not assessed in this study. Sixth, because this study followed a cross-sectional design, the long-term effects were compared between groups comprising different participants. In addition, the content of the CC of Thoracic Surgery, in which the students in the control group rotated, was different from that of Respiratory Medicine. Although EBM-focused education was not included in Respiratory Medicine and Thoracic Surgery other than the WB-EBM program, individual supervisors may have provided instructions on EBM. However, the influence of such independent instructions on the results was not excluded.

Conclusions

The WB-EBM program during CC motivated medical students to formulate and critically examine their clinical questions. Although medical students used requotation from secondary literature, such as guidelines and PubMed searches, they had limited interest in the year of publication of the literature. Furthermore, the long-term effect of the WB-EBM programs on students’ behavior and self-evaluation regarding EBM practice can last for several months, but such effects may diminish or disappear afterwards. Therefore, WB-EBM programs may need to be repeated across departments over a CC period to effectively change behaviors in the practice of EBM.

Supplemental Material

Download PNG Image (56.9 KB)Acknowledgments

We would also like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2024.2357411

Additional information

Funding

References

- Quill TE, Rg H. Evidence, preferences, recommendations — finding the right balance in patient care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(18):1653–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1201535

- Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JAM, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it Isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71–72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71

- Densen P. Challenges and opportunities facing medical education. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2011;122:48–58.

- Islam MS, Sarkar T, Khan SH, et al. COVID-19–related infodemic and its impact on public health: a global social media analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103(4):1621–1629. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0812

- Crilly M, Glasziou P, Heneghan C, et al. Does the current version of ‘tomorrow’s doctors’ adequately support the role of evidence-based medicine in the undergraduate curriculum? Med Teach. 2009;31(10):938–944. doi: 10.3109/01421590903199650

- Blanco MA, Capello CF, Dorsch JL, et al. A survey study of evidence-based medicine training in US and Canadian medical schools. J Med Libr Assoc. 2014;102(3):160–168. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.102.3.005

- Medical Education Model Core Curriculum Expert Research Committee. Model Core Curriculum for Medical Education in Japan, 2022 Revision. [cited 2023 Mar 15]. Available from: https://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/shingi/chousa/koutou/116/toushin/mext_01280.html

- Ahmadi S-F, Baradaran HR, Ahmadi E. Effectiveness of teaching evidence-based medicine to undergraduate medical students: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2015;37(1):21–30. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.971724

- Hirt J, Nordhausen T, Meichlinger J, et al. Educational interventions to improve literature searching skills in the health sciences: a scoping review. J Med Libr Assoc. 2020;108(4):534–546. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2020.954

- Khan KS, Coomarasamy A. A hierarchy of effective teaching and learning to acquire competence in evidenced-based medicine. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6(1):59. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-59

- Oude Rengerink K, Thangaratinam S, Barnfield G, et al. How can we teach EBM in clinical practice? An analysis of barriers to implementation of on-the-job EBM teaching and learning. Med Teach. 2011;33(3):e125–130. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.542520

- Ismach RB. Teaching evidence-based medicine to medical students. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(12):e6–10. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.08.037

- Kasai H, Saito G, Ito S, et al. Literature search skills of Japanese medical students in clinical clerkship - the current status and effects of brief guidance. Igaku Kyoiku/Med Educ (Japan). 2020;51:389–399.

- Dawes M, Summerskill W, Glasziou P, et al. Sicily statement on evidence-based practice. BMC Med Educ. 2005;5(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-5-1

- Ilic D, Tepper K, Misso M. Teaching evidence-based medicine literature searching skills to medical students during the clinical years: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Libr Assoc. 2012;100(3):190–196. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.100.3.009

- Ghali WA, Saitz R, Eskew AH, et al. Successful teaching in evidence-based medicine. Med Educ. 2000;34(1):18–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00402.x

- Engel B, Esser M, Bleckwenn M. Piloting a blended-learning concept for integrating evidence-based medicine into the general practice clerkship. GMS J Med Educ. 2019;36(6):Doc71. doi: 10.3205/zma001279

- Sánchez-Mendiola M, Kieffer-Escobar LF, Marín-Beltrán S, et al. Teaching of evidence-based medicine to medical students in Mexico: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12(1):107. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-12-107

- Just ML. Is literature search training for medical students and residents effective? A literature review. J Med Libr Assoc. 2012;100(4):270–276. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.100.4.008

- Mithoefer MC, Mithoefer AT, Feduccia AA, et al. 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans, firefighters, and police officers: a randomised, double-blind, dose-response, phase 2 clinical trial. Lancet Psych. 2018;5(6):486–497. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30135-4

- Greenhalgh T. How to read a paper: The basics of evidence-based medicine. John Wiley & Sons; 2014.

- Elwyn G, Quinlan C, Mulley A, et al. Trustworthy guidelines – excellent; customized care tools – even better. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):199. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0436-y

- Guyatt G, Rennie D, Meade M, et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: a manual for evidence-based clinical practice. 3rd ed. JAMAevidence. McGraw Hill Medical. Available from: https://jamaevidence.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?

- Kyriakoulis K, Patelarou A, Laliotis A, et al. Educational strategies for teaching evidence-based practice to undergraduate health students: systematic review. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2016;13:34. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2016.13.34

- Rees E, Sinha Y, Chitnis A, et al. Peer-teaching of evidence-based medicine. Clin Teach. 2014;11(4):259–263. doi: 10.1111/tct.12144

- Weatherall DJ, Ledingham JGG, Warrell DA. On dinosaurs and medical textbooks. Lancet. 1995;346(8966):4–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)92646-1

- Gruppen LD, Rana GK, Arndt TS. A controlled comparison study of the efficacy of training medical students in evidence-based medicine literature searching skills. Acad Med. 2005;80(10):940–944. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200510000-00014

- Shekelle PG, Ortiz E, Rhodes S, et al. Validity of the agency for healthcare research and quality clinical practice GuidelinesHow quickly do guidelines become outdated? JAMA. 2001;286(12):1461–1467. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.12.1461

- Shojania KG, Sampson M, Ansari MT, et al. How quickly do systematic reviews go out of date? A survival analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(4):224–233. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-4-200708210-00179

- Menard L, Blevins AE, Trujillo DJ, et al. Integrating evidence-based medicine skills into a medical school curriculum: A quantitative outcomes assessment. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2021;26(5):249–250. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111391

- Ramos KD, Schafer S, Tracz SM. Validation of the fresno test of competence in evidence based medicine. BMJ. 2003;326(7384):319–321. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7384.319

- Fritsche L, Greenhalgh T, Falck-Ytter Y, et al. Do short courses in evidence based medicine improve knowledge and skills? Validation of berlin questionnaire and before and after study of courses in evidence based medicine. BMJ. 2002;325(7376):1338–1341. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7376.1338