ABSTRACT

Introduction

Since 2022, all Canadian post-graduate medical programs have transitioned to a Competence by Design (CBD) model within a Competency-Based Medical Education (CBME) framework. The CBME model emphasized more frequent, formative assessment of residents to evaluate their progress towards predefined competencies in comparison to traditional medical education models. Faculty members therefore have increased responsibility for providing assessments to residents on a more regular basis, which has associated challenges. Our study explores faculty assessment behaviours within the CBD framework and assesses their openness to opportunities aimed at improving the quality of written feedback. Specifically, we explore faculty’s receptiveness to routine metric performance reports that offer comprehensive feedback on their assessment patterns.

Methods

Online surveys were distributed to all 28 radiology faculty at Queen’s University. Data were collected on demographics, feedback practices, motivations for improving the teacher-learner feedback exchange, and openness to metric performance reports and quality improvement measures. Following descriptive statistics, unpaired t-tests and one-way analysis of variance were conducted to compare groups based on experience and subspecialty.

Results

The response rate was 89% (25/28 faculty). 56% of faculty were likely to complete evaluations after working with a resident. Regarding the degree to which faculty felt written feedback is important, 62% found it at least moderately important. A majority (67%) believed that performance reports could influence their evaluation approach, with volume of written feedback being the most likely to change. Faculty expressed interest in feedback-focused development opportunities (67%), favouring Grand Rounds and workshops.

Conclusion

Assessment of preceptor perceptions reveals that faculty recognize the importance of offering high-quality written feedback to learners. Faculty openness to quality improvement interventions for curricular reform relies on having sufficient time, knowledge, and skills for effective assessments. This suggests that integrating routine performance metrics into faculty assessments could serve as a catalyst for enhancing future feedback quality.

Background

Since 2022, all Canadian postgraduate medical programs have transitioned to a Competence by Design (CBD) model within a Competency-Based Medical Education (CBME) framework [Citation1,Citation2]. The CBD model was developed by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC) and serves as a structured approach to CBME. This model is broken down into four sequential stages (Transition to Discipline, Foundations of Discipline, Core of Discipline, and Transition to Practice). Residents progress through each stage by demonstrating adequate achievement of Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs), which represent specialty-specific tasks that residents are evaluated on [Citation2]. In traditional medical education models, faculty assessments of residents were often periodic and less frequent, focusing primarily on summative evaluations. In contrast, the CBME model emphasizes more frequent, formative assessment of residents to evaluate their progress towards predefined competencies [Citation3]. As such, faculty members now have increased responsibility for providing assessments to residents on a more regular basis [Citation4]. This paradigm shift underscores a growing need for feedback that is specific, constructive, and actionable. Moreover, extensive literature supports trainees’ strong desire for meaningful feedback, therefore aligning with the feedback-driven approach of CBME [Citation5–8].

The implementation of CBME has not been without challenges. Since the early adoption of CBME in 2017 (five years ahead of the national timeline) at our institution, challenges such as faculty and resident commitment to the assessment program and competing time demands have been identified as factors that hinder faculty from completing high-quality evaluations on resident learners. Interviews and focus groups with residents and program staff using the Rapid Evaluation methodology revealed a consensus across all stakeholders on the importance of more frequent and timely feedback in CBME. However, it was also reported that residents often felt a disconnect between this perceived benefit and the reality of not receiving written feedback as expected.

Numerous other studies, both preceding and following the implementation of CBME, have documented challenges in attaining quality written feedback [Citation9–13]. One theme that emerged is a preference among staff and residents for verbal feedback over written feedback. Despite an increase in feedback forms since the implementation of CBME, residents perceive a lack of meaningful and overall dissatisfaction with the quality or quantity of written feedback received [Citation9–14]. These findings are further supported by a 2024 study from Clement et al. that evaluated narrative comments on assessment forms across 24 Canadian residency programs active in CBME. They found that most scores fell within the lower to middle quality scale [Citation13]. These collective findings underscore the persistent challenge in ensuring effective feedback mechanisms within CBME frameworks.

To address these challenges, several studies have explored methods to improve faculty feedback practices, including resident-to-faculty feedback, faculty development workshops, and formal feedback training sessions [Citation15–17]. In many workplaces, employers routinely receive metric reports to evaluate their performance. However, while faculty physicians may receive reports on clinical metrics (such as patient or case volume), feedback on their feedback practices is not commonly provided. To date, there is a paucity of research that has assessed the feasibility of implementing metric reports on feedback practices, and findings are limited due to low power [Citation17].

As part of our effort to improve the quality of evaluation data provided by faculty to trainees, we explored how faculty members perceive and respond to feedback on their performance as assessors. Our study aimed to explore faculty perceptions of their assessment patterns, assess their openness to training opportunities to improve their evaluation skills, and ultimately assess their openness to the use of metrics reports. By addressing these issues, we sought to contribute valuable insights to optimizing the faculty’s role in resident assessment within the evolving medical education landscape.

Context

Our Diagnostic Radiology program accepts three residents per year. On a typical day, residents work through a list of imaging cases and draft their preliminary reports. They review with the faculty radiologist usually twice per day (once in the morning and once in the afternoon) to go over their completed cases and make corrections as necessary. The time spent reviewing is dependent on the individual staff and the residents’ level of training (e.g., final year residents may not review x-rays with staff unless they have questions). Following review of cases, staff finalize the reports.

The CBME model encourages residents to seek out regular assessments from their preceptors, ideally multiple times a week. These assessments allow the staff to evaluate and provide formal documentation on the resident’s performance on predefined competencies, often through a combination of written feedback and rating scales. At the end of each assessment form, preceptors are asked to determine whether they feel the resident has attained a level of ‘competence’ for a specific Entrustable Professional Activity (EPA) which is indicative of their ability to work autonomously (termed ‘achievements’). Residents must obtain a minimum number of achievements for each EPA to quality for promotion. These evaluations can be initiated by either the supervisor or the resident and can be for a single case or a batch of cases. Ideally, they are completed during or shortly after the encounter. In practice, staff often complete written evaluations on their own time, which can be days to months after the encounter.

Faculty members may hold additional administrative positions. For example, an Academic Advisor is one who is assigned a resident and is responsible for assessing the resident’s learning trajectory throughout their training. Competence Committee members assess EPA evaluations across all residents and determine their fit for promotion.

Methods

Study design

This was an online survey of full-time faculty radiologists at Queen’s University (Appendix 1). The study received approval from the hospital’s Research Ethics Board.

Survey design and content

A survey was created to evaluate the perspectives of faculty radiologists on routine feedback metric reports (Appendix 1). The survey focused on identifying perceived challenges and benefits to gauge the feasibility of integrating these feedback systems into routine practice. Following review of the literature, the survey was developed by the research team which consisted of three expert staff radiologists (each possessing over five years of experience in CBME and a strong interest in enhancing feedback practices), resident input from one trainee, and a research statistician. Survey questions were organized into four main categories: 1) demographic information (e.g., faculty subspecialty, years of experience), 2) current feedback practices, 3) faculty motivations for improving the teacher-learner feedback exchange, and 4) preferred content and distribution of metric reports. Respondents were allowed to select more than one answer option where applicable (e.g., a respondent could select ‘academic advisor’, ‘competence committee member’ and ‘faculty instructor’ if they fulfilled all of these roles).

Recruitment

From August to October 2023, the survey was disseminated electronically to all 28 faculty radiologists at our institution. Financial support for this project was secured from the Department of Diagnostic Radiology Research Grant, thereby enabling the provision of $50 CAD gift card incentives to all survey respondents.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in consultation with a research statistician (WH) to discern common themes related to improvement strategies. Group statistics, categorized by years of experience (>10 years versus <10 years) and faculty subspecialty fields, were applied to specific survey questions using chi-square tests. Unpaired T-tests and one-way ANOVAs were employed to analyze Likert scale data as means. Statistical significance was considered at p ≤ 0.05. Data was organized in tabular and graphical formats.

Results

Demographics

The survey had a completion rate of 89% (25/28) from the Queen’s University Diagnostic Radiology faculty. shows the key demographic information of survey respondents. Six of the department’s seven subspecialities were represented. One sub-specialty (nuclear medicine) was not represented due to lack of completion by the 1 eligible respondent. Most respondents (80%) held additional administrative positions (defined as program lead, department lead, CBME lead, Academic Advisor, or Competence Committee member). A slight majority (56%) had over 10 years of experience, while 44% had 10 or less years of experience.

Table 1. Queen’s University diagnostic radiology faculty demographics.

Current feedback practices

Most respondents (72%) dedicated between 1–2 hours per day reviewing cases and providing feedback, a minority (20%) spent 3+ hours, and even fewer (8%) spent less than 1 hour on these tasks. Approximately half of the respondents (56%) indicated they were either ‘likely’ or ‘very likely’ to complete a written evaluation after working with a resident, while 24% stated they were ‘unlikely’ or ‘very unlikely’ to do so. Only 36% reported they were ‘likely’ or ‘very likely’ to complete the evaluation within 48 hours. Additionally, nearly half (48%) were ‘likely’ or ‘very likely’ to have their written feedback align with their verbal feedback. The majority of respondents (54%) were ‘likely’ or ‘very likely’ to adjust their written feedback to a learner’s specific level of training ().

Figure 1. Likelihood of written feedback to: (1) adjust to the learner’s level and provide feedback tailored to the resident’s specific learning needs [top]; (2) relate to the relevant stage of training, ensuring feedback is appropriate for the resident’s level; (3) reinforce well-performed tasks; (4) include specific strategies for improvement; and (5) identify areas needing improvement [bottom].

![Figure 1. Likelihood of written feedback to: (1) adjust to the learner’s level and provide feedback tailored to the resident’s specific learning needs [top]; (2) relate to the relevant stage of training, ensuring feedback is appropriate for the resident’s level; (3) reinforce well-performed tasks; (4) include specific strategies for improvement; and (5) identify areas needing improvement [bottom].](/cms/asset/17f028f9-9ccd-4680-a04d-22f629996781/zmeo_a_2357412_f0001_oc.jpg)

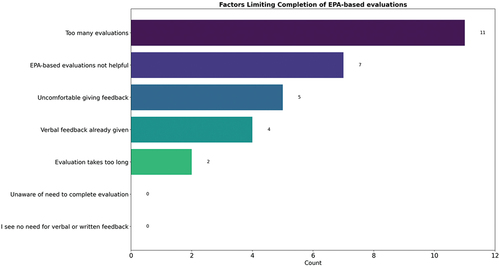

Among the preset reasons cited by faculty for limiting their completion of evaluations, faculty were most likely to be concerned over the frequency of evaluations (). Some faculty (29%) also expressed skepticism regarding the effectiveness of these evaluations in aiding resident development. Other reasons included the time-consuming nature of evaluations and discomfort in providing feedback after the encounter.

Figure 2. Limiting factors for completion of EPA-based evaluations. Respondents could also provide open-ended responses.

We also asked respondents to elaborate on additional factors hindering their completion of evaluation forms. Common themes included a preference for verbal feedback over written feedback, and the perception that written feedback is redundant. Concerns were raised about the quality of evaluations, including delayed feedback delivery, and the lack of specific assessments for soft skills. Moreover, some respondents expressed skepticism towards the CBME model, viewing it as inefficient and lacking evidence of superiority over previous educational models.

Faculty motivations

Most respondents (74%) had not undergone any faculty development course or formal training in feedback provision. All respondents felt it was at least moderately important to not only provide high-quality narrative feedback to residents, but also to obtain feedback from trainees. Some respondents (42%) were ‘unsatisfied’ or ‘very unsatisfied’ with their current state of providing written feedback to learners. Most staff (79%) expressed motivation to improve their ability to provide quality feedback.

Content and distribution of metric reports

The majority of respondents thought it would at least be moderately useful to receive feedback from faculty peers on their written evaluations. Additionally, 67% felt this feedback could influence their evaluation practices, possibly in the volume of feedback or turnaround times ().

Table 2. Faculty survey responses.

When asked what content they would like to see included in these metric reports, at least half of respondents reported they would like to see the: 1) total number of evaluations completed, 2) average scoring provided to residents, 3) scores relative to their peers, 4) average turnaround times, and 5) ranking relative to other faculty. Half of respondents (50%) would either be interested in or would be open to the use of expert assessors to grade their evaluation forms (‘yes’ or ‘maybe’).

Regarding whom should have access to these metric reports, 50% felt only the individual should have access, and 68% felt the program director should have access. There was no consensus for the preferred frequency of report distribution, with responses ranging from monthly to every 9–12 months.

Open feedback was collected to help inform future improvement strategies for CBME. While a detailed qualitative analysis was not performed on this data, recurring themes were identified and described in .

Table 3. Open-ended faculty feedback responses.

Subgroup analysis

For survey questions employing a Likert scale, unpaired T-Tests were conducted to discern any nuanced differences between faculty with more than 10 years and less than 10 years of experience. The mean value for the Likert scales (ranging between 1 and 5 for everyone) was used to identify any variance. Although results were not statistically significant, the group with greater experience consistently scored higher on the Likert scale. Additionally, a one-way ANOVA test was conducted to compare response differences among faculty subspecialty groups, and no significant difference was observed between the groups.

Discussion

Current culture of feedback

In this study, we describe the unique challenges that postgraduate residency programs face in delivering high-quality documented feedback in the new CBME model. Our findings show that faculty unanimously acknowledge the importance of delivering high-quality feedback to learners. However, a significant portion of faculty are dissatisfied with their current feedback delivery practices. Additionally, only 56% of faculty members are likely to complete an assessment form for the learner. These results build on the published literature in which the importance of quality narrative feedback in CBME is reported by both trainees and preceptors, yet the actual documentation of consistent quality feedback can be challenging [Citation18,Citation19]. While preceptors may have a genuine desire to offer valuable feedback to residents, this intention is often hampered by time constraints, particularly in environments where faculty members lack dedicated time specifically allocated for providing feedback [Citation20]. Further complicating the matter is the lack of rigorous oversight over the completion of assessment forms. This leaves residents frustrated, frequently citing issues with receiving feedback that is timely, actionable and specific [Citation21].

Another factor to consider is the lack of formal feedback training in medical education. About 75% of our survey respondents reported having no formal training in precepting. While some faculty development units offer formal training such as workshops, short courses, and online webinars, motivating physician participation remains challenging [Citation22]. Preceptors face the dilemma of insufficient protected time, underestimation of their training needs, and lack of personal motivation. Few studies have explored the effects of intensive teacher training on medical educators’ performance [Citation23–25]. The results have been conflicting; some suggest an improvement in teaching ability, while others report a decline in teaching efficacy. Ultimately, this highlights a gap between faculty expectations and the support necessary to facilitate continuous learner assessment.

Our findings show that faculty prefer verbal feedback over written feedback. Such a preference is reinforced by existing literature, with Johnson et al.. (2016) demonstrating how verbal feedback’s immediate nature serves as a catalyst for improved clarity and introspection [Citation26]. Similarly, Molloy and Denniston (2019) described the benefits of a dialogic approach within surgical training [Citation27]. These approaches, which prioritize contextual and interactive dialogue, highlight the superiority of verbal feedback for real-time adaptability and educational depth. Nevertheless, written feedback should ideally complement verbal feedback by acting as a means of idea reinforcement and documentation purposes. Monitoring resident progress, guiding their learning, providing evidence to competence committees, and identifying residents who are struggling are vital components of the assessment process. These tasks are typically best achieved through the documentation of written feedback [Citation9].

To address these complexities, a coordinated effort is needed at the local and national level. Programs must offer clear guidance regarding what the evaluations should encompass so that it can adequately capture essential aspects of resident performance. Other strategies include initiating professional development opportunities, tailoring feedback improvement strategies (including considering gender dynamics) and reassessing the culture of feedback at the institution. Finally, allocating dedicated time for resident feedback exchanges with staff can facilitate open dialogue and foster honest, comprehensive feedback.

Role of metric reports and expert reviewers in feedback improvement

Few studies evaluate the efficacy of metric reports in improving faculty feedback practices [Citation28]. Given that a significant majority (79%) of faculty at our institution expressed a motivation to improve their feedback quality, there is potential for favorable reception of metric reports. These reports can provide objective data for performance measurement and contextualize a faculty member’s evaluation practices relative to their peers. They may serve as motivation for those below the mean, and validation for those above it. Nevertheless, the use of metric reports warrants careful consideration. Programs should prioritize maintaining anonymity and selecting metrics that are both meaningful and respectful of faculty preferences. Potential metrics could encompass evaluation completion rates, comparative scoring averages, turnaround times, and peer rankings. Thoughtful selection of these metrics aimed at delivering substantial value can facilitate continuous improvement in feedback quality.

Incorporating expert reviewers into the feedback system also offers an opportunity for refining feedback practices. Not all faculty in our study expressed interest in metric reports, suggesting there may be variability in the reception of such feedback mechanisms. For successful integration of expert reviewers, one must carefully consider the logistical and practical challenges. Reviewers must be familiar with the nuances of CBME assessment techniques. Steps must be taken to safeguard anonymity and avoid a punitive approach. Expert reviewers should therefore ideally be faculty from different departments than the preceptor being evaluated. A pilot program could introduce these experts as partners rather than overseers, emphasizing collaborative efforts rather than critique. This initiative should prioritize preserving faculty autonomy and morale throughout its implementation.

Alternative feedback improvement strategies

We explored alternative methods for improving feedback provision. One study explored faculty development workshops which can offer a collaborative environment conducive to learning, but their time-intensive nature can be challenging for busy faculty members [Citation29]. Alternative methods, such as web-based and mobile app-based platforms, may be feasible for their convenience and immediacy [Citation30–33]. Cue cards and audio feedback strike a middle ground, offering succinct and personalized guidance [Citation18]. Video review has the potential for comprehensive feedback, but these require a significant investment in time for both recording and analysis [Citation34,Citation35]. Our finding suggest that the majority of physicians believe feedback interventions that integrate smoothly into faculty’s daily activities (such as grand rounds) may present the least resistance and preserve existing workflows. Conversely, while online modules and comprehensive workshops hold substantial educational value, their extensive time requirements render them less practical, pointing towards the need to alleviate the burden on faculty schedules.

Another strategy to consider is resident-driven feedback. Most respondents in our study expressed a strong preference for insights directly from residents. However, eliciting candid feedback from residents to faculty can be challenging, primarily due to the hierarchical nature of medical training. Residents may hesitate to offer open feedback, fearing negative consequences on their evaluations and future opportunities [Citation36,Citation37]. Moreover, the requirement for faculty to obtain favorable evaluations for career advancement can discourage them from providing candid criticism, leading to a preference for more positive feedback [Citation38]. Such a tendency could dilute the intended educational value of the feedback, inadvertently hindering the growth of residents. To mitigate this, institutions should prioritize the educational quality of feedback over its positivity. Initiatives such as establishing a specific day dedicated to resident feedback could foster a safer and more open exchange of views. Anonymized feedback mechanisms could further alleviate the fear of professional consequences for both residents and faculty.

Need for targeted approaches

Amidst differing faculty needs, targeted approaches are necessary to address the diverse challenges faced by preceptors. While there was no statistical significance in results categorized by sub-specialty fields, select specialty-specific feedback emphasized the importance of accommodating unique challenges within different disciplines. For example, in rotations such as interventional radiology where procedural competency is central to the learning curve, concerns were raised about the need for at least two weeks of direct supervision to adequately assess the resident. While statistical significance may not have been achieved due to the sample size, this underscores the importance of adapting to distinct sub-specialty needs. Flexible evaluation tools tailored to each sub-specialty’s requirements may be essential for meaningful assessments [Citation11,Citation39].

Limitations

One limitation of our study is the generalizability of our data. It involved a small sample size that was based out of a single department within a single Canadian institution. Therefore, caution should be exercised in directly applying our findings to other institutions or healthcare systems in different countries due to divergent regulations, requirements, and resources that impact the implementation and effectiveness of CBME. The findings need to be replicated in other specialties and contexts. Further research needs to focus on larger sample sizes in order to generate more information on the attitudes associated with different groups (e.g., taking into account characteristics such as gender, age, academic background, years of experience). This type of research could also be enhanced by incorporating more face-to-face, in-depth discussions about faculty’s emotional and pragmatic responses to resident feedback.

Feedback dynamics are also influenced by gender. While we did not specifically examine gender differences, evidence shows that gender dynamics play a role in feedback processes in medical training [Citation40]. Male physicians more typically favor in-person feedback. Conversely, female counterparts may prefer written feedback and often revisit learning objectives post-feedback [Citation41]. Additionally, female residents tend to receive more feedback when mentored by female preceptors [Citation42]. These nuances point to an opportunity for future research to investigate how gender influences feedback perception and practice in medical education.

An inherent limitation of our study is the potential for selection bias. Selection bias may have arisen due to the voluntary nature of participation in our study, particularly as it relates to faculty members’ willingness to share perceptions of feedback practices. Such bias could mean that our sample may not be fully representative of the broader faculty population, possibly skewing our findings towards those who are more engaged with or have stronger opinions about feedback mechanisms. For instance, faculty members who are either particularly satisfied or dissatisfied with the current feedback culture might have been more inclined to participate, while those with neutral views may have been underrepresented. Future studies could aim to mitigate selection bias through stratified sampling techniques or by ensuring a broader representation.

Conclusion

This study provides insight into faculty perceptions and assessment patterns in radiology education. Faculty unanimously recognize the importance of providing high-quality written feedback to learners. Faculty’s readiness for curricular reform relies on receiving sufficient time, knowledge, and skills to efficiently carry out their assessments. A key future step involves supplying these resources and considering the implementation of routine metric reports to aid faculty feedback improvement. Most faculty view metric reports as beneficial for refining evaluation methods, enabling them to track resident evaluation completions and obtain feedback on these evaluations. This, in turn, is expected to enhance the overall quality of the preceptor-resident feedback exchange. Our findings not only contribute valuable insights to our institution, but also offer a foundation for ongoing research and targeted improvements in faculty development programs in the era of CBME.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Competence by design: reshaping Canadian medical education. Ottawa (ON): Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2014.

- Kwan BYM, Mbanwi A, Cofie N, et al. Creating a competency-based medical education curriculum for Canadian diagnostic radiology residency (Queen’s fundamental innovations in residency education)—Part 1: transition to discipline and foundation of discipline stages. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2021;72(3):372–12. doi: 10.1177/0846537120983082

- Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, et al. Competency based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):638–645. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190

- George SJ, Manos S, Wong KK. Preparing for CBME: how often are faculty observing residents? Paediatr Child Health. 2021;26(2):88–92. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxaa164

- Van Melle E, Frank JR, Holmboe ES, et al. A core components framework for evaluating implementation of competency-based medical education programs. Acad Med. 2019;94(7):1002–1009. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002768

- Gauthier S, Braund H, Dalgarno N, et al. Assessment-seeking strategies: navigating the decision to initiate workplace-based assessment. Teach Learn Med. 2023 Jun 29:1–10. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2023.2229803

- Mishra S, Chung A, Rogoza C, et al. Creating a competency-based medical education curriculum for Canadian diagnostic radiology residency (Queen’s fundamental innovations in residency education)-Part 2: core of discipline stage. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2021;72(4):678–685. doi: 10.1177/0846537120983083

- Chung AD, Kwan BYM, Wagner N, et al. An adaptation-focused evaluation of Canada’s first competency-based medical education implementation in radiology. Eur J Radiol. 2022;147:110109. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2021.110109

- Tomiak A, Braund H, Egan R, et al. Exploring how the new entrustable professional activity assessment tools affect the quality of feedback given to medical oncology residents. J Cancer Educ. 2019;35(1):165–177. doi: 10.1007/s13187-018-1368-1

- Hajar T, Wanat KA, Fett N. Survey of resident physician and attending physician feedback perceptions: there is still work to be done. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25(12). doi: 10.5070/D32512046687

- Rizwan AP, Cofie N, Mussari B, et al. What is the minimum? A survey in procedural competency in diagnostic radiology in the era of competency based medical education. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2022;73(2):422–425. doi: 10.1177/08465371211040262

- Hamza DM, Hauer KE, Oswald A, et al. Making sense of competency-based medical education (CBME) literary conversations: a BEME scoping review: BEME guide no. 78. Med Teach. 2023;45(8):802–815. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2023.2168525

- Clement EA, Oswald A, Ghosh S, et al. Exploring the quality of feedback in entrustable professional activity narratives across 24 residency training programs. J Grad Med Educ. 2024 Feb;16(1):23–29. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-23-00210.1 Epub 2024 Feb 17. PMID: 38304587; PMCID: PMC10829927.

- Branfield Day L, Miles A, Ginsburg S, et al. Resident perceptions of assessment and feedback in competency-based medical education: a focus group study of one internal medicine residency program. Acad Med. 2020 Nov;95(11):1712–1717. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003315 PMID: 32195692.

- Wong L, Chung AD, Rogoza C, et al. Peering into the future: a first look at the CBME transition to practice stage in diagnostic radiology. Acad Radiol. 2023;30(10):2406–2417. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2023.06.013

- Salerno SM, Jackson JL, O’Malley PG. Interactive faculty development seminars improve the quality of written feedback in ambulatory teaching. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(10):831–834. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20739.x

- Pincavage A, Cifu A. Faculty member feedback reports. Clin Teach. 2015;12(1):50–54. doi: 10.1111/tct.12246

- Chiu A, Lee GB. Assessment and feedback methods in competency-based medical education. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021 Dec;127(6):681–687. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2021.12.010 PMID: 34813912.

- Hanson JL, Rosenberg AA, Lane JL. Narrative descriptions should replace grades and numerical ratings for clinical performance in medical education in the United States. Front Psychol. 2013;4:668. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00668 eCollection 2013. PMID: 24348456; PMCID: PMC3842007.

- Cheung K, Rogoza C, Chung AD, et al. Analyzing the administrative burden of competency based medical education. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2022 May;73(2):299–304. doi: 10.1177/08465371211038963 Epub 2021 Aug 27. PMID: 34449283.

- Chacko TV. Giving feedback in the new CBME curriculum paradigm: principles, models and situations where feedback can be given. JETHS. 2022;8(3):76–82. doi: 10.18231/j.jeths.2021.016

- Matthiesen M, Kelly MS, Dzara K, et al. Medical residents and attending physicians’ perceptions of feedback and teaching in the United States: a qualitative study. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2022;19:9. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2022.19.9

- Hartford W, Nimmon L, Stenfors T. Frontline learning of medical teaching: “you pick up as you go through work and practice”. BMC Med Educ. 2017 Sep 19;17(1):171. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-1011-3

- Steinert Y, Mann K, Centeno A, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME guide no. 8. Med Teach. 2006;28(6):497–526. doi: 10.1080/01421590600902976

- Mitchell JD, Holak EJ, Tran HN, et al. Are we closing the gap in faculty development needs for feedback training? J Clin Anesth. 2013;25(7):560–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2013.05.005

- Johnson CE, Keating JL, Boud DJ, et al. Identifying educator behaviours for high quality verbal feedback in health professions education: literature review and expert refinement. BMC Med Educ. 2016 Mar 22;16(1):96. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0613-5

- Nestel, D. Advancing surgical education: theory, evidence and practice. 1st ed. Singapore: Springer; 2019. p. 978–981–13–3127–5, 978–981–13–3128–2.

- Berk RA. Start spreading the news: use multiple sources of evidence to evaluate teaching. J Fac Dev. 2018;32(1):73–81.

- Khan AM, Gupta P, Singh N, et al. Evaluation of a faculty development workshop aimed at development and implementation of a competency-based curriculum for medical undergraduates. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2020 May 31;9(5):2226–2231. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_17_20 PMID: 32754478; PMCID: PMC7380743.

- Choi HH, Clark J, Jay AK, et al. Minimizing barriers in learning for on-call radiology residents—end-to-End web-based resident feedback system. J Digit Imaging. 2018;31(1):117–123. doi: 10.1007/s10278-017-0015-1

- Tanaka P, Bereknyei Merrell S, Walker K, et al. Implementation of a needs-based, online feedback tool for anesthesia residents with subsequent mapping of the feedback to the ACGME milestones. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(2):627–635. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001647

- Tenny SO, Schmidt KP, Thorell WE. Pilot project to assess and improve neurosurgery resident and staff perception of feedback to residents for self-improvement goal formation. J Neurosurg. 2020;132(4):1261–1264. doi: 10.3171/2018.11.JNS181664

- Gray TG, Hood G, Farrell T. The results of a survey highlighting issues with feedback on medical training in the United Kingdom and how a smartphone app could provide a solution. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):653. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1649-z

- Topps D, Evans RJ, Thistlethwaite JE, et al. The one minute mentor: a pilot study assessing medical students’ and residents’ professional behaviours through recordings of clinical preceptors’ immediate feedback. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2009;22(1):189.

- Wouda JC, Van De Wiel HBM. The effects of self-assessment and supervisor feedback on residents’ patient-education competency using videoed outpatient consultations. Patient Education And Counseling. 2014;97(1):59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.05.023

- Albano S, Quadri SA, Farooqui M. et al. Resident perspective on feedback and barriers for use as an educational tool. Cureus. 2019 May 10;11(5):e4633. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4633 PMID: 31312559; PMCID: PMC6623994.

- Delva D, Sargeant J, Miller S, et al. Encouraging residents to seek feedback. Med Teach. 2013;35(12):e1625–e1631. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.806791

- Karm M, Sarv A, Groccia J. The relationship between students’ evaluations of teaching and academics professional development. J Further Higher Educ. 2022;46(8):1161–1174. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2022.2057214

- Pugh D, Cavalcanti RB, Halman S, et al. Using the entrustable professional activities framework in the assessment of procedural skills. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(2):209–214. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00282.1

- Mueller AS, Jenkins TM, Osborne M, et al. Gender differences in attending physicians’ feedback to residents: a qualitative analysis. J Grad Med Educ. 2017 Oct;9(5):577–585. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-17-00126.1

- Jones Y, Murray P, Strader R, et al. Gender and feedback in medical education [version 1]. MedEdpublish. 2018;7:35. doi: 10.15694/mep.2018.0000035.1

- Loeppky C, Babenko O, Ross S. Examining gender bias in the feedback shared with family medicine residents. Educ Prim Care. 2017;28(6):319–324. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2017.1362665

Appendix 1.

CBME survey questions

Demographics

Which of the following title best describes you? (select all that apply)

☐ Department Head, Associate Department Head, Postgraduate Program Director, or CBME Lead

☐ Academic Advisor

☐ Competence Committee Member

☐ Faculty instructor/preceptor

Which specialty-training best describes you?

☐ Musculoskeletal

☐ Neuroradiology

☐ Body Radiology

☐ Cardiothoracic radiology

☐ Paediatric radiology

☐ Interventional radiology

☐ Breast radiology

☐ Nuclear Medicine

How many years of experience do you have in a teaching faculty role?

☐ 0–1☐1–4☐5–10☐10+

What best describes how often you work with a diagnostic radiology resident (percentage of days working at your principal institution)?

☐ <25%☐25–50%☐50–75%☐75–100%

When working with a diagnostic radiology resident, how long do you take per day to review cases/provide feedback?

☐ <1 hour☐ 1–2 hours☐ 3–4 hours☐ >4 hours

Current feedback practices

After working with a diagnostic radiology resident, how likely are you to complete an EPA-based evaluation?

☐ Very likely

☐ Likely

☐ Neutral

☐ Unlikely

☐ Very unlikely

If giving both verbal and written feedback, how likely is the written feedback to completely capture what is said verbally?

☐ Very likely

☐ Likely

☐ Neutral

☐ Unlikely

☐ Very unlikely

How likely are you to regularly complete an EPA-based evaluation within 48 hours?

☐ Very likely

☐ Likely

☐ Neutral

☐ Unlikely

☐ Very unlikely

How likely is your written feedback to:

What are factors that limit your completion of EPA-based evaluations and/or how much written feedback you provide? Check all that apply.

☐ Too many evaluations to complete

☐ Takes too long to complete an evaluation

☐ I feel uncomfortable giving feedback after the observation

☐ I was not aware that I was supposed to complete an evaluation

☐ I do not see the need to complete evaluations if verbal feedback has already been given

☐ I do not believe that these EPA-based evaluations help the resident

☐ I neither see the need to provide verbal nor written feedback

☐ Other (please specify)

Improving the teacher-learner feedback exchange

Have you undergone any faculty development course or formal training in providing feedback?

☐ Yes

☐ No

How important do you feel it is for learners to receive high-quality narrative feedback?

☐ Very important

☐ Important

☐ Moderately important

☐ Of little importance

☐ Unimportant

How satisfied are you with your current state of providing written documentation/feedback to learners after assessment of their performance?

☐ Very satisfied

☐ Satisfied

☐ Moderately satisfied

☐ Unsatisfied

☐ Very unsatisfied

How motivated are you to improve your ability to provide high-quality feedback to learners?

☐ Very motivated

☐ Motivated

☐ Neither motivated or unmotivated

☐ Unmotivated

☐ Very unmotivated

Is feedback provided by resident learners important to you?

☐ Very important

☐ Important

☐ Moderately important

☐ Of little importance

☐ Unimportant

Would feedback from faculty peers (specifically pertaining to your narrative feedback on EPA-based evaluations) be useful?

☐ Very important

☐ Important

☐ Moderately important

☐ Of little importance

☐ Unimportant

Do you think that being provided information/feedback on your EPA-based evaluations would change how you complete EPA-based evaluations?

☐ Yes☐ No☐ Maybe

If yes to the above, which of the following might change? Check all that apply.

☐ Number of EPA evaluations

☐ EPA turnaround times (time from observation of EPA to completion of evaluation)

☐ Volume of written feedback

☐ Other (please specify)

Content and distribution of metric reports

We are looking into the usefulness of routine metric reports that allow you to track the completion of your evaluation forms and provide feedback on their quality, so as to improve the overall preceptor-resident feedback exchange. The following questions pertain to this metric report.

If metric reports were to be distributed, who should see/review these metric reports? Check all that apply.

☐ Only yourself

☐ Program Director

☐ Department Head

☐ All faculty

☐ Other (please specify)

How often should these metric reports be distributed?

☐ Monthly

☐ Every 2–4 months

☐ Every 4–6 months

☐ Every 6–9 months

☐ Every 9–12 months

What is your preferred method for receiving these reports?

☐ Elentra

☐ Other (please specify)

Would you be interested in the use of expert assessors to grade your EPA-based evaluation forms and/or provide feedback on how to improve the quality of evaluation forms?

☐ Yes☐ No☐ Maybe

What other information would you like to see included in these metric reports? Check all that apply.

☐ Total number of evaluations completed within a timeframe (e.g., per year)

☐ Average scoring provided to residents

☐ Scores relative to peers (e.g., % of evaluations marked as ‘achieved’ compared to other faculty)

☐ Evaluation form turnaround times

☐ Word count on written feedback

☐ Ranking relative to other faculty (e.g., rank of turnaround times, rank of number of evaluations completed)

☐ None

☐ Other (please specify)

Would you be interested in attending faculty development on feedback? If yes, which format is preferred?

☐ Yes, in workshop format

☐ Yes, in individualized sessions

☐ Yes, through online modules

☐ Yes, through Grand Rounds

☐ Yes, other (please specify)

☐ No

Any other comments?

By clicking ‘submit’, you consent to the use of your data for this research study. Please note that data cannot be withdrawn upon submission of your answers.