Abstract

Building on research showing social-emotional benefits from a single live theater performance, this study tests for significant differences in pre to post social-cognitive outcomes among a racially and economically diverse sample of young audiences who attended the same theater performance with or without additional pre- and post-show educational experiences. We extend previous work by experimentally manipulating and testing a common artistic educational intervention: deeper engagement strategies including facilitated discussions and pre-performance guides. We also refine previous investigations into generalized social and emotional skills by specifically examining foundational social-cognitive abilities: social perspective taking and empathy. This study utilizes a pre-post design with randomized control and treatment groups. Several significant findings suggest that when paired with educational pre- and post-show experiences, students’ social perspective taking and empathy can be positively impacted through a single live theater performance.

Highlights

Theater experiences for students are often paired with before and after engagement activities

The effects of discussion activities on empathy and engagement in theater are unknown

Experimentally comparing pre-show, post-show, and no discussion showed effects on Affective Empathy

Reading preparation moderated the relation between various treatments and outcomes

Students with little/no prior theater experience benefited more from the treatment

In-show engagement can be boosted and impacts students’ social-emotional skills

Social and emotional skills are critically important to child development. Interventions to improve these skills are numerous, and their proponents enthusiastic, but are only sometimes rigorously tested before being widely applied (Lee et al., Citation2015; Mcclelland et al., Citation2017). One 2017 such theorized intervention is involvement in the arts, and in particular, attending theater. Within arts communities, theater is often theorized to be particularly useful for developing children's emotional and social abilities when it is paired with various educational tools and techniques such as talkbacks and preparatory readings (Glass et al., Citation2020; Reason, Citation2010; Woods-Robinson, Citation2018). Yet how, when, and for whom these activities cause gains is yet unknown. Here we rigorously test various ways in which children can attend a theatrical performance, and how attendance and paired activities differentially affect social perspective taking and empathy.

Social-Emotional learning

Social and emotional skills encompass children’s understanding of their own and others’ emotions, management of their emotions and social interactions, engagement in prosocial behaviors, and building and maintenance of positive relationships with others (CASEL, Citation2020; Denham et al., Citation2003; Merrell et al., Citation2008; Weissberg & Cascarino, Citation2013). These skills have critically important impacts, both concurrent and longitudinal, on children’s lives. Fostering social emotional learning (SEL) has been linked to higher levels of school readiness and higher academic achievement (Curby et al., Citation2015; Garner & Waajid, Citation2008; Izard et al., Citation2001), development of successful peer and interpersonal relationships (Denham et al., Citation2003), and higher levels of prosocial behavior (Campos et al., Citation2004; Eisenberg & Zhou, Citation2000). Less adaptive SEL has long-lasting, negative outcomes including low academic achievement (Domitrovich et al., Citation2017), dysfunctional relationships with others (Denham et al., Citation1990), and internalizing or externalizing problems (Bowie, Citation2010; Kalpidou et al., Citation2004). Specific SEL emotional processes such as empathy and perspective taking have been linked to emotional health and well-being, behavioral adjustment, and academic achievement (Burchinal et al., Citation2020), underscoring the importance of interventions aimed at positive growth in social perspective taking and empathy in the school-age years. These interventions have taken multiple forms, including training programs, teaching programs and professional learning, SEL curricula, arts programs, and many others.

Social-emotional learning and the arts

Engagement in the arts and arts education have been studied as a potent intervention across multiple academic disciplines, age groups, time spans, and social emotional outcomes (for in-depth reviews, see Farrington et al., Citation2019; Goldstein et al., Citation2017; Holochwost et al., Citation2017). Correlational studies indicate that various experiences with arts and arts education are positively related to several social and emotional competencies in children spanning from Pre-K to 12th grade (Holochwost et al., Citation2021; Lee et al., Citation2015). For example, high school dance classes (Carter, Citation2005), middle school music instruction (Degé et al., Citation2009), and elementary school improvizational theater (DeBettignies & Goldstein, Citation2020) have been linked to students’ self-concept. Dance instruction has also been linked to elementary students’ self-efficacy (Lee, Citation2006). More generally, high school students who participated in any arts have shown higher levels of school engagement than peers who did not participate in the arts (Elpus, Citation2013). Acting, drama, and theater participation have been linked to empathy in elementary and high school students (Goldstein & Winner, Citation2012), tolerance in elementary (Gourgey, Citation1985) and high school (Beales & Zemel, Citation1990), positive feelings about school (DICE Consortium, Citation2010), and gains in self efficacy (Catterall, Citation2007). Additionally, a meta-analysis examining drama-based pedagogy found positive effects of drama activities and framing devices on academic and social emotional outcomes (Lee et al., Citation2015).

In adults, exposure to literature, particularly literary fiction, has been associated with higher levels of empathy and the related construct of theory of mind (Bal & Veltkamp, Citation2013; Djikic et al., Citation2013). While some experimental findings have shown immediate connections between reading fiction and theory of mind (Kidd & Castano, Citation2013), this finding has failed to reliably replicate (Panero et al., Citation2016; Samur et al., Citation2018). Parents who recognize more book authors or report more reading do have children with higher empathy and theory of mind (Adrian et al., Citation2005; Aram & Aviram, Citation2009; Mar et al., Citation2010). Importantly, though, we do not have strong evidence for the causal direction of these findings: findings in both adults and children are often correlational, with experiments producing both positive and null associations between fiction and empathy (Mar, Citation2018). There seems to be strong evidence for lifetime associations, but weaker evidence for any immediate fiction reading experience. Less intensive, single art experiences have also been shown to impact social and emotional outcomes in a handful of causal studies. For example, visits to an art museum have been linked to increased critical thinking, empathy, and tolerance (Greene et al., Citation2014), and a single live theater performance was shown to have a causal impact on tolerance and social perspective taking (Greene et al., Citation2018) in one study, and increased empathy and monetary donations in a series of pre-registered field studies (Rathje et al., Citation2021), indicating that live theater performances are a possible method of SEL intervention.

The current study builds upon and extends the work of Greene et al. (Citation2018), Rathje et al. (Citation2021), and their respective colleagues by testing for significant differences in social cognitive outcomes among a racially and economically diverse sample of young audiences from urban and suburban schools who attended the same theater performance at the Kennedy Center with or without additional various engagement experiences. Critically important, the current study goes beyond asking whether mere attendance at a theatrical play affects SEL by experimentally manipulating and testing a common artistic educational intervention: deeper engagement strategies such as facilitated discussions and pre-performance guides. We also refine previous investigations into generalized social and emotional skills by specifically examining foundational social cognitive abilities: social perspective taking and empathy.

Social perspective taking

Social perspective taking (SPT) describes the process through which individuals perceive the thoughts, feelings and motivations of others and is often linked to theory of mind and cognitive empathy (Gehlbach, Citation2004a; Gehlbach et al., Citation2012a). SPT skills develop early and increase over time, but fully realized SPT requires a level of abstract thinking and complex cognitive processes not typically present until the entry to high school (Martin et al., Citation2008). In the literature, SPT is characterized from both social-emotional (Diazgranados et al., Citation2016) and cognitive perspectives (Gehlbach et al., Citation2015; Selman, Citation1975). For the purposes of the current study, we conceptualize SPT as closely aligning with the skills in the social awareness competency of the Collaborative for Academic and Social Emotional Learning’s SEL framework (CASEL, Citation2020), while also falling under the umbrella of social cognitive abilities. Theoretically, SPT is made up of two components: the motivation to engage in SPT and the ability to perform SPT accurately. Improving SPT is important because it is theorized as a ‘cascading’ skill, meaning it is causally linked to several other important SEL skills such as increased self-esteem, increased positive well-being, and adaptive conflict-resolution (Gehlbach et al., Citation2012a). In addition, students with higher levels of SPT have been shown to be more skillful in supporting close relationships with teachers and peers and tend to receive higher grades (Gehlbach, Citation2004b). Research suggests SPT can be taught and facilitated in school-aged students and adults (Gehlbach et al., Citation2012b). Classroom activities that utilize constructive controversy such as mock trials and debates (Johnson et al., Citation2000) and assignments that emphasize perspective taking can be used to engage students in SPT and bolster their utilization of perspective taking in everyday life (Gehlbach, Citation2004b).

Empathy

While empathy has been defined in a multitude of ways (Decety & Jackson, Citation2004; Elliott et al., Citation2011; Gerdes et al., Citation2010), for the purposes of this study, we understand empathy to be an accurate assessment of another individual’s affective state, and the subsequent, appropriate emotional response to that affect. This focus on affect is what primarily distinguishes empathy from SPT. Current research makes the distinction between two primary types of empathy (Cuff et al., Citation2016; Davis, Citation1983; Gerdes et al., Citation2010). Cognitive empathy refers to understanding another’s emotion, while affective empathy refers to the degree to which the empathizer tends to vicariously experience the emotions of the target of their empathy (Jolliffe & Farrington, Citation2006). The construct of empathy blurs the line between social-emotional and social-cognitive skills, but empathy can still be located under the social awareness competency of the CASEL SEL framework. As with SPT, higher levels of empathy are associated with adaptive outcomes for young students (Gleason et al., Citation2009), and by adolescence increased empathy has been linked to more positive perceptions of school culture (Barr & Higgins-D'Alessandro, Citation2007) and lower levels of bullying behaviors (Jolliffe & Farrington, Citation2006). While there is strong evidence in the literature for the importance of empathy and SPT development in young children, less is known about how interventions not specifically developed to change these skills might work. For our purposes, whether growth in these related constructs may be affected by mechanisms such as those present in a live theater intervention and targeted engagement experiences.

The current study: deeper engagement through pre- and post-performance experiences

While previous research has found positive social and emotional learning from engaging in theater as both a performer and an audience member (Farrington et al., Citation2019; Goldstein et al., Citation2017), this study’s primary innovation is the experimental manipulation of multiple components of pre- and post-performance engagement experiences, investigated as possible amplifiers of the adaptive social-emotional effects thought to be conveyed from a live theater experience. Pre- and post-performance engagement provides students opportunities to explore the content and themes of the show and can be targeted toward specific topics or outcomes (Glass et al., Citation2020). Pre- and post-performance engagement is common in theater for young audiences and is seen to give young audience members the tools they need to effectively process and understand the content they see on stage (Donelan & Sallis, Citation2013; Reason, Citation2010; Woods-Robinson, Citation2018). Additionally, pre- and post-performance engagement can serve as repetition of themes and content for students, which is a strategy frequently used in education to enhance students’ learning (Blackwell, Citation2019; Fitzgibbon, Citation1993). We tested the effectiveness of a Performance Guide, an informative guide sent to teachers to use in preparing their classroom for their trip to the theater both generally and for their specific performance, as well as a Facilitated Discussion, in which audience members engage in a conversation after the show that is facilitated by an external content matter expert. Finally, we compared the combination of both Performance Guide and Facilitated Discussion experiences relative to single experiences or the live theater performance without additional engagement. Because these experiences are commonly used in the performing arts educational context, results from the current study will inform educators and arts venues across the country who develop such material. In addition to planned and embedded pre- and post-performance experiences utilized in the current study, additional student preparation and experience was measured to determine impact on SPT and empathy through interactions with treatment group assignment. Interactions between students' prior experience, preparation, and engagement before, during, and after attending a live theater performance are likely a more realistic reflection of mechanisms for increasing SPT and empathy compared to considering singular main effects.

Of particular note is that this performance could allow for preparation through reading. The live theater performance used in the current study is a modern hip-hop re-imagining of Mark Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper, which is available in book format. Unfortunately, we were unable to randomly assign participants to read or not read the book because of the independence of teacher and school choices. However, participants were asked if they had read the book prior to attending the live theater performance, and we controlled for this in our analyses. Reading a related book could deepen students’ engagement with the performance and its content, which could lead to larger gains in SPT and/or empathy than attending the theater performance without having read the book. It is also possible that reading paired with other pre- and post-performance experiences in the current study (i.e. the Performance Guide and the Facilitated Discussion) could compound this effect, leading to a larger impact on students’ SEL than the experiences or the reading could on their own.

Finally, several specific indicators of engagement are beneficial to consider for theater for young audiences. Prior knowledge, including preparation and personal connections to a theme, memory, or idea in the performance tend to foster engagement (Christenson et al., Citation2012). Second, engagement is more than behavioral participation – it requires feelings and sense-making as well as activity (Harper & Quaye, Citation2009). Taken together with evidence from work at the Kennedy Center suggesting that students with prior preparation or experience with arts lessons were more likely to be positively engaged at performances, there is sufficient evidence to ask whether prior theater experience and engagement through preparation might be important moderators of change in SPT and empathy resulting from a single live theater performance with accompanying pre- and post-performance experiences.

Research questions

The study asks the following questions:

Do participants who attend a live theater performance show significant growth in SPT and empathy, as measured before and after the show, compared to controls?

Do pre/post-performance preparation and experiences systematically moderate growth in SPT and empathy?

Do participants who engage in in-class or reading preparation before the performance have higher levels of in-show audience engagement?

Do participants who have prior theater experience have higher levels of in-show audience engagement?

Is this effect stronger for those currently participating in theater experiences?

Do higher levels of in-show audience engagement predict significant change in SPT and empathy?

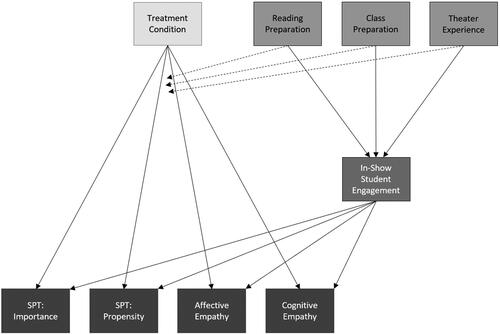

The full conceptual model reflecting these research questions can be seen below in .

Figure 1. Full Conceptual Model.

Note: Dashed lines represent moderation analyses that were conducted for each moderator (Reading Preparation, Class Preparation, and Theater Experience) on each treatment to outcome relationship. Only three of these lines are included to aid in readability of the figure.

Method

All aspects of this study were approved by Integ Review IRB and all appropriate consents and assents were collected.

Participants

The sample consisted of 2,389 students from 19 middle schools in two school districts. Students were randomized (at the classroom/teacher level) into one of five groups. The groups were A: Control (958 students), B: Live Theater Performance Only (275 students), C: Live Theater Performance + Performance Guide (386 students), D: Live Theater Performance + Facilitated Discussion (402 students), and E: Live Theater Performance + Performance Guide + Facilitated Discussion (368 students). See for a full description of student sample sizes by treatment group and time point.

Table 1. Treatment Group Sample Sizes.

The student sample was diverse and representative of the geographic area in which the study was conducted. Students self-identified through demographic questions on the survey as Hispanic/Latino (27.8%), Black/African American (21.5%), and White (19.8%), with other races/ethnicities making up smaller percentages of the sample. The diversity of the current sample helps to extend existing work in this area to a broader student population. The age of the sample ranged from 10 to 15 years old, with most students falling in the middle at 12 (56.3%) or 13 (20.9%) years old. Students identified as female (50%) and male (41%), in addition to smaller percentages of students identifying as non-binary (0.72%), choosing to self-describe (1.08%), or declining to report their gender (7.2%).

Measures

The Social Perspective Taking-Motivation Survey (Gehlbach et al., Citation2012a) is a 16-item Likert-type scale measuring factors of SPT-Propensity and SPT-Importance. Response options are on a 1–5-point scale, ranging from ‘Almost never’/‘Not at all important’ to ‘Almost all of the time’/‘Extremely important’. The survey has been used with adults, college students, and 7th-12th graders (Gehlbach et al., Citation2012a), and was the SPT measure of choice in the Greene et al. (Citation2018) study that the current study builds upon. Cronbach’s Alpha values for the current study data were α = .86 for the pre time point and α = .89 for the post time point.

The Basic Empathy Scale (Jolliffe & Farrington, Citation2006) is a 20-item Likert-type scale measuring subscales of Cognitive and Affective Empathy. Response options are on a 5-point scale, ranging from ‘Strongly disagree’ to ‘Strongly agree’. The survey has been validated with 10th grade students (Jolliffe & Farrington, Citation2006). Cronbach’s Alpha values for the current study data were α = .84 for the pre time point and α = .87 for the post time point.

The Preparation, Experience, and In-seat Engagement items used in the current study were developed and compiled by the Kennedy Center Research and Evaluation team. Preparation items reflect students’ self-reported in-class preparation prior to the show, and their reading preparation of The Prince and the Pauper. Experience items reflect students’ prior and current experience with theater. Finally, Engagement items reflect students’ self-reported engagement with the live theater performance. The items were validated with 5th-12th grade adolescents and have been used previously as an in-seat survey by the study authors. These items were administered once at the post time point; Cronbach's Alpha was α = .79.

Procedures

Performance guide administration

Performance Guides are youth-facing resources that provide context for learning about themes, concepts, and self-expression opportunities related to a theater program for young audiences (Reason, Citation2010). The Performance Guide for this production was designed for teachers to use with their students before and after performances and contain introductory information and activities appropriate for all students, including those who do not attend the performance. Teachers in treatment groups C (Performance + Performance Guide) and E (Performance + Performance Guide + Facilitated Discussion) were provided with a Performance Guide to present to their students three days before their scheduled performance date. The Performance Guide included an introduction and overview of Hip Hop culture, the six elements of Hip Hop culture, suggestions for what to reflect upon before, during, and after the performance, and engagement activities with reflection questions. The full Performance Guide can be seen in Appendix A.

Participating teachers were instructed to distribute the Performance Guides one or two school days before their scheduled performance. Teachers were advised to use the Performance Guides as a tool to prepare and debrief their students. Pages two and three were written as preparation for the performance, and pages three and four for after the performance. Teachers were encouraged to use their professional judgment on the length and format of the instruction related to the performance guide.

Teachers who received Performance Guides were also asked to participate in a thirteen question post-performance survey to gauge how they used the provided materials. All thirteen teachers reported distributing the Performance Guides to their students in the participating classrooms. The time teachers reported spending using the Performance Guide to prepare their students for the performance varied. Six of the thirteen teachers (46.15%) spent 11 − 20 minutes, three teachers (23.08%) spent 21 − 30 minutes, and four teachers (30.77%) spent more than 30 minutes preparing with the Performance Guide before the performance.

Facilitated discussion administration

Facilitated Discussions are intended to offer an opportunity to explore and examine the themes and content presented on-stage in a post-show discussion. Led by a guest facilitator, Facilitated Discussions engage audiences in conversation to unpack themes presented on stage.

Facilitated Discussions for the current study were designed to be driven by reflexive student-centered discussion. While the content for Facilitated Discussions varied from performance to performance based on students’ thoughts and responses to the production, the format of the conversation always followed the same questioning structure, a scaffolded invitation to “describe, analyze, and relate” (a modified version of Bloom’s Citation1956 Taxonomy; see Appendix B for scripted Facilitated Discussion questions and prompts):

Priming the conversation: Before the production, the facilitator offered a prompt for students to consider while they watched the show. This prompt was based on the learning objectives identified by the team and was the same for each discussion.

Invitation to Discussion: Directly following the performance, the facilitator began with an invitation to describe what students witnessed by inviting them to respond to the prompt posed at the beginning of the show. The invitation to discussion invited students to consider the specific actions and emotions that characters experienced.

Analysis: The facilitator posed a series of questions that respond to audience engagement, interest, and thoughts. Analysis was student-driven, and the content discussed varied based on students’ responses. The facilitator drew on questions grounded in learning objectives developed with education team members in pre-planning.

Reflection: Following the analysis, the facilitator concluded discussion with an invitation for students to engage in self-reflexive discussion on the themes and content explored in the performance. This provided an opportunity for students to engage actively in social perspective taking and empathy by inviting them to respond directly to characters’ thoughts, emotions, and circumstances. Reflection allows students and the facilitator to bring closure to the discussion while laying foundations for future analysis and reflection after students have left the theater.

Teachers and students in treatment groups D (Performance + Facilitated Discussion) and E (Performance + Performance Guide + Facilitated Discussion) participated in a Facilitated Discussion with an external teaching artist. The teaching artist, who facilitated all five discussions, asked students to critically examine the themes of the play, if they saw parallels to their own life, and which of the two main characters they most related to and why. The Facilitated Discussions all used the same prompts throughout and were observed to range from 5 to 12 minutes in length.

Survey administration

A team of eleven researchers (six data collectors and five research assistants) visited the participating schools to administer the pre and post surveys. Schools requested either paper or electronic (SurveyMonkey) surveys. Surveys were available in English and Spanish, through translation by a bilingual research assistant. Parental consent forms were delivered in person to schools 1-2 weeks before the start of pre survey administration. Each school sent an estimated number of forms needed in both English and Spanish. Data collectors visited each classroom, introduced the survey, collected any returned parental consent forms, administered student assent forms, and administered surveys. For post surveys, all data collectors administered assents to any students who were not present for the pre survey, collected any additional parental consent forms, and administered the survey.

On average, across all treatment groups and all students who participated in the study, there were 15.65 days between the when students took the pre survey and when they attended the performance (range = 1 to 23 days), 5.29 days between the performance and the post survey (range = 1 to 15 days), and 17.70 days between the pre survey and the post survey (range = 7 to 30 days). The times between surveys and performances were not found to vary significantly when analyzed by treatment group.

Data analysis

High levels of internal consistency supported the calculation of composite scores. Following the instructions provided by measure developers, composite scores were calculated as the mean of item responses at the scale level and subscale level for SPT, empathy, and student in-show engagement. These composite scores were used in all subsequent analyses. Responses for preparation and experience items were summed to obtain a total score for each variable.

Unconditional models

Unconditional multilevel models were fit to estimate the variance in outcome measures due to levels of nesting in the data. Three-level models were used to account for student, teacher, and school levels. From the unconditional models, intraclass correlations (ICCs) were calculated and were relatively low (below .10 or 10% of variance), indicating students’ teachers and schools did not account for much of the observed variance in SPT and empathy scores. Regardless of the low ICCs, analyses were conducted in a multilevel framework to account for the nesting of the data.

Baseline equivalence

Pre-survey scores on measures of interest were tested for equivalence as defined by the What Works Clearinghouse (Citation2020). Hedges’ g (Hedges, Citation1981) was used to assess baseline equivalence on all pre intervention measures of interest. Regression adjusted means were used (from the unconditional models described above) to account for the nested nature of the data. Hedges’ g values below .05 indicate baseline equivalence, values between .05 and .25 indicate equivalence when statistical adjustment is used in subsequent analyses (e.g., controlling for baseline), and values above .25 indicate nonequivalence that cannot be corrected through statistical adjustment. Baseline levels of SPT and empathy for all treatment groups were compared to each other. Of all the comparisons (40 in total), two were found to be unequal at baseline above the .25 level that cannot be controlled for in analyses. Both instances of nonequivalence were for treatment group B (Performance Only), which is the smallest group. Group B (Performance Only) was found to be nonequivalent to groups C (Performance Guide) and E (Performance Guide + Facilitated Discussion) in SPT: Propensity. Though this did not affect the analysis plan moving forward, any results for these nonequivalent groups on SPT:P should be interpreted with care and the nonequivalence considered as a limitation. Analyses were also conducted to test for balance in our treatment groups by available demographic variables (student self-reported gender, race/ethnicity, and age), and groups were found to have no significant differences based on these characteristics (all ps>.05). Additionally, no significant differences were found in demographics or pre-survey scores when comparing participants who completed only the pre survey to those who completed both pre and post surveys (all ps>.05).

Impact analyses and student engagement analyses

Analyses were conducted using Stata statistical software (version 16.1). All impact analyses are multilevel mixed-effects regression models that included race, gender, age, and pre-survey scores as controls.

The goal of Research Question 1 (Do participants who attend a live theater performance show significant growth in SPT and empathy, as measured before and after the show, compared to controls?) was to test for main effects of the live theater performance, the Performance Guide, and the Facilitated Discussion. The Performance Guide and Facilitated Discussion groups are combinations of two treatment groups given that some students received just the Performance Guide or the Facilitated Discussion, while other students received both the Performance Guide and the Facilitated Discussion. The combination of these groups was a planned aspect of the analysis plan aimed to assess the impact of the Performance Guide and Facilitated Discussion both in their respective singular treatment groups and in combination across groups.

Given the number of conditions present and number of possible comparisons, we did not compare every group and condition to each other condition, but rather chose the more parsimonious approach of comparing each treatment group individually to the control group to test for main effects of each group and comparing each possible main effect to its respective control group in search of main effects. For example, to test the main effect of the live theater performance, all treatment groups combined (B, C, D, E) were compared to the control group (theater performance vs. no theater performance). Treatment group B individually was also compared to the control group (theater performance only vs. no theater performance). Similarly, to test for a main effect of the Performance Guide, treatment groups that received the Performance Guide (C and E) were compared to all groups that did not receive the Performance Guide (any Performance Guide condition vs. no Performance Guide). Treatment group C individually was compared to the control group (Performance Guide only condition vs. no performance and no Performance Guide). This same approach was taken to test for a main effect of the Facilitated Discussion.

To answer Research Question 2 (Do pre/post-performance preparation and experiences systematically moderate growth in SPT and empathy?) interaction effects were tested for Reading Preparation, Class Preparation, and Experience, in combination with all treatment groups and the Performance Guide and Facilitated Discussion conditions. These analyses included interaction terms in the multilevel models for all treatment groups individually and for the Performance Guide and Facilitated Discussion conditions (combinations of two treatment groups each). As with Research Question 1, each condition was compared to its relative control groups. For example, groups who received the Facilitated Discussion (D and E) were compared to all groups that did not receive the Facilitated Discussion, and treatment group D (Facilitated Discussion only) was compared to the control group individually. Conducting the analyses in this manner allowed for logical interpretation of results that lends itself to application of findings (e.g., students in treatment group E were significantly higher in post empathy than the control group only if they reported the lowest level of theater experience).

Research Questions 3, 4, and 5 asked whether students’ Class or Reading Preparation or their Theater Experience relate to their reported in-show engagement during the performance, and whether that engagement relates to the outcomes of SPT and empathy. To address these questions, multilevel regression analyses were run with the full treatment sample to test for relations between the Preparation and Theater Experience variables, and students’ in-show Engagement, and then for relations between students’ in-show Engagement and the SPT and empathy outcome variables. These analyses were done with the combined treatment sample (B, C, D, E), did not include the control group, and did not include treatment group as a predictor in the models.

See below for a summary of all models run by research question (e.g., Model 1.1 is the first model for research question 1), groups compared, and effects tested.

Table 2. Summary of Models.

Results

The percent of missing data for the whole sample from pre to post was 6.57%. Statistically significant differential missingness was found for treatment group E (Performance Guide and Facilitated Discussion) on outcome variables such that group E was missing significantly more data when compared to other groups. However, Cohen’s D effect sizes for these differences ranged from 0.13 to 0.17, which are considered to be small effect sizes, and the differences in percentage points for missingness between group E and the control group (in addition to the overall attrition rate) are within What Works Clearinghouse standards for low attrition and tolerable threat of bias (What Works Clearinghouse, Citation2020). No pre-survey or demographic variables were found to predict missingness in the sample. Results (Beta coefficients) for all impact and student engagement analyses can be found in .

Table 3. Beta Coefficients for Impact and Student Engagement Analyses by Research Question.

Impact analyses

Research question 1

The first research question asked whether participants who attend a live theater performance show significant growth in SPT and empathy, as measured before and after the show, compared to controls. This question was addressed through testing for main effects of all treatment groups individually. As noted above, testing the main effects of the Performance Guide and Facilitated Discussion groups required combining groups C and E (for the Performance Guide) and D and E (for the Facilitated Discussion). A main effect of Facilitated Discussion (groups D and E) was observed (Model 1.4), such that Facilitated Discussion participants showed significantly higher post-survey Affective Empathy scores compared to students who did not participate in a Facilitated Discussion (β=.056, p=.019). No other significant main effects emerged for the theater performance overall, for any of the treatment groups individually, or for the Performance Guide (Models 1.1–1.3).

Research question 2

The second research question asked whether pre/post-performance preparation and experiences systematically moderate growth in SPT and empathy. This question was addressed by testing interaction effects for Reading Preparation, Class Preparation, and Experience, in combination with all treatment groups and the Performance Guide and Facilitated Discussion conditions. Five significant interactions emerged for the Reading Preparation variable. Students in treatment group E (Performance Guide and Facilitated Discussion) with more Reading Preparation (Model 2.1) were significantly higher in post-survey SPT: Propensity (β=.397, p=.044) and Cognitive Empathy (β=.411, p=.024) than other students. Students in a Performance Guide condition (groups C and E) with more Reading Preparation (Model 2.2) were significantly higher in post-survey Affective Empathy (β= .238, p=.031) and Cognitive Empathy (β= .441, p<.001) than students not in a Performance Guide condition. Finally, students in a Facilitated Discussion condition (groups D and E) with more Reading Preparation (Model 2.3) scored significantly higher in post-survey Cognitive Empathy (β=.204, p=.049) than students who did not participate in a Facilitated Discussion.

Three significant interactions emerged for the Class Preparation variable. Students in treatment group D (Facilitated Discussion) with more Class Preparation (Model 2.1) were significantly lower in post-survey SPT: Propensity (β=−.435, p=.013). Additionally, students in treatment group B (performance only) with more Class Preparation (Model 2.1) were significantly lower in post-survey Affective Empathy (β=−.548, p=.001) than other students. Students in a Performance Guide condition (groups C and E) with more Class Preparation (Model 2.2) were significantly higher in post-survey Cognitive Empathy (β=.238, p=.024) than other students.

Two significant interactions emerged for Theater Experience. Students in treatment group E (Performance Guide and Facilitated Discussion) with the lowest Theater Experience (Model 2.1) were significantly higher in post-survey Affective Empathy (β= .240, p=.036), and students in treatment group B (performance only) with mid-level Theater Experience (Model 2.1) were significantly lower in post-survey Affective Empathy (β=−.272, p=.022) than other students.

Student engagement analyses

The remaining Research Questions (3, 4, and 5) asked whether students’ Preparation and Theater Experience relate to their in-show engagement during the performance, and whether their engagement relates to the outcomes of SPT and empathy. These questions were addressed through tests for relations between the Preparation and Theater Experience variables, and students’ in-show Engagement, and then for relations between students’ in-show Engagement and the SPT and empathy outcome variables. These analyses were done with the treatment sample only (that is, the sample did not include the members of the control group A) and did not include treatment as a predictor in the models. Students who participated in Class Preparation before attending the performance (Model 3.1) reported significantly higher levels of in-show Engagement (β=.167, p<.001) than students who did not participate in Class Preparation. Students who read the related book before attending the performance (Model 3.1) reported significantly higher levels of in-show Engagement (β=.134, p=.001) than students who did not read the book. Students who had prior Theater Experience (Model 4.1) reported significantly higher levels of in-show Engagement (β=.109, p<.001) than students with no Theater Experience. Additionally, students who were currently participating in theater (Model 4.1) reported significantly higher levels in-show Engagement (β=.364, p<.001) than students with no Theater Experience and students with prior (but not current) Theater Experience. Furthermore, higher student in-show Engagement (Model 5.1) predicted higher levels of post-survey Affective Empathy (β=.138, p=.001), Cognitive Empathy (β=.090, p=.046), Social Perspective Taking: Propensity (β= .205, p<.001), and Social Perspective Taking: Importance (β=.189, p<.001) regardless of treatment condition.

Discussion

Building on previous research that has found positive social and emotional learning from engaging with theater (e.g. Goldstein & Winner, Citation2012; Greene et al., Citation2018), this study experimentally manipulated multiple components of pre- and post-performance engagement experiences, and investigated these components as possible amplifiers of the adaptive social-emotional effects thought to be conveyed from a live theater experience. Because pre- and post-performance engagement is common in theater for young audiences (Reason, Citation2010; Woods-Robinson, Citation2018), understanding how various types of engagement impact student outcomes is critical for our own work, in addition to the field of theater for young audiences more broadly. To this end, we tested the impact of a Performance Guide and a Facilitated Discussion and compared the combination of both Performance Guide and Facilitated Discussion experiences relative to single experiences or the live theater performance without additional engagement. Other student experiences such as reading a book related to the live theater performance and prior engagement with theater were also considered as moderators of the impact of treatment conditions on student outcomes of social perspective taking and empathy. Taken together, our results show causal effects of discussion, preparation, engagement, and theatrical experience on the Social perspective taking and empathy of a diverse middle school sample. The current study produced several important findings that help build knowledge around live theater performances as psychosocial interventions, and students’ social-emotional skills.

Results for research question 1

Research Question 1 asked whether participants who attend a live theater performance show significant growth in SPT and empathy, as measured before and after the show, compared to controls. The main effect of the Facilitated Discussion on students’ Affective Empathy indicates that even a short (12 minutes or less) discussion paired with a live theater performance can impact students’ reports of their ability to experience and share the emotions of others. This main finding has important implications for performing arts organizations and in school settings, as Facilitated Discussions can be a relatively simple addition to existing field trips or to classroom curricula or events involving theater. Importantly, the topic of this show was the importance and consequences of being able to see the world through someone else’s perspective; that is, definitionally, the show was about empathy. Other theatrical experiences on other topics may show different effects, or shows with explicit messages about empathy may be unique in their ability to cause change in children’s social perspective taking. On the other hand, as theater is always about people taking on situations differently than oneself, this effect could also be generalizable across the themes of plays; future research will need to determine the role of plot and setting.

Results for research question 2

Research Question 2 asked whether pre/post-performance preparation and experiences systematically moderate growth in SPT and empathy. The moderators tested were Reading Preparation, Class Preparation, and Theater Experience. Reading Preparation moderation effects show a clear pattern. Students’ reading of The Prince and The Pauper prior to attending the performance significantly moderated the relation between the various treatment conditions and the Social Perspective Taking: Propensity, Affective Empathy, and Cognitive Empathy outcomes. These positive outcomes suggest that reading the book prior to the performance boosts the effects of the treatment conditions, perhaps due to the time commitment, detail, and deeper level of understanding that may come with reading the book. It is also possible that the repetition of material and themes provided by reading the related book and then seeing the performance solidify learning and enhance treatment effects for students (Kang, Citation2016; Saville, Citation2011), or that we are seeing more general effects of reading fiction, as have been previously reported (Black et al., Citation2021; Mar, Citation2018). As many theater shows have related books, this method of deeply engaging students in content and fostering social-emotional outcomes could be easily and readily utilized in various other settings.

Moderation effects for Class Preparation do not paint as clear a picture, as some students with higher Class Preparation were found to be higher in Cognitive Empathy, while other students with higher Class Preparation were found to be lower in Social Perspective Taking: Propensity and Affective Empathy. We did not control for or collect data on the type or amount of Class Preparation that students received. As such, a range of experiences may be captured through the item on Class Preparation. For example, a five-minute conversation about how to behave at the theater (or on the bus ride over) could be reported as Class Preparation, but so could a 40-minute lesson on the themes of pretending to be someone you are not and putting yourself in the shoes of a character. Future research or attempts at replication should at minimum, collect more specific data on Class Preparation, and ideally, articulate a protocol for Class Preparation before a live theater performance within the treatment conditions to further test its impact on social-emotional outcomes.

Moderation effects for Theater Experience are also somewhat mixed: students in one treatment with low Theater Experience showed higher Affective Empathy, but students in another treatment with mid-level Theater Experience showed lower Affective Empathy. The positive result for students with low Theater Experience may reflect a novelty effect in that students with little to no prior Theater Experience benefited more from the treatment than did students with more Theater Experience. It is worth noting that the negative effect found for mid-level Theater Experience was with treatment group B (performance only), which is the same group that had the negative effect for Class Preparation. This treatment group was the smallest out of all groups and was the only group that had any nonequivalence emerge while testing for baseline equivalence. For these reasons, all findings with treatment group B (both of which are negative) should be interpreted with care.

Results for research questions 3–5

Research Questions 3, 4, and 5 asked whether students’ Preparation or Theater Experience relate to in-show engagement during the performance, and whether that engagement relates to the outcomes of SPT and empathy, regardless of treatment condition. Results suggest that students’ in-show engagement during a live theater performance was increased through participation in Class or Reading Preparation before attending the performance, and through both prior and current theater experiences such as attending other performances or taking theater classes. Higher student in-show Engagement in turn related to higher levels of empathy regardless of treatment condition. These results indicate that high in-show engagement can increase empathy following a theater performance, and that furthermore, that in-show engagement can be boosted through various preparations and experiences prior to the performance. Implications for these findings are broad, as many theater shows have related books, and opportunities are numerous for Class Preparation. Additionally, prior and current theater experience may have an additive or compounding effect, such that the more students are exposed to theater, the more engaged they will be at future theater performances.

Limitations

The findings of the current study need to be considered in the context of study limitations. All data in the current study are self-reported, meaning we capture a single perspective rather than triangulating results across multiple methods of data collection. Additionally, study authors received feedback from a few participating teachers that some of the survey questions contained language that may have been above their students’ reading levels, particularly for students toward the lower end of the age range (10 years of age). This information is anecdotal, and the instruments used were validated with middle and high schoolers, and showed strong Cronbach’s alphas, but should still be taken under consideration.

Fidelity to Performance Guide instructions was measured using a self-report teacher survey, which revealed some variation in how teachers used the guide with their students. Most teachers in a Performance Guide condition (69%) followed our recommendation to distribute and use the Performance Guide one to two days before the performance. Additionally, most teachers (76%) followed our recommendation to use the Performance Guide as a debrief tool following the performance.

Facilitated Discussions were originally intended to last around 15 minutes and consist of back-and-forth conversation between the students and the facilitator. In practice, the Facilitated Discussions were shorter in length than planned, and involved mostly yes/no questions due to a lower level of student engagement and participation than anticipated. Despite this limitation, several results emerged around the Facilitated Discussion condition. Significant results from a less-than-perfect Facilitated Discussion execution suggest that a perfectly executed Facilitated Discussion could have an even larger impact on students’ empathy and social perspective taking. Future research should further explore post-performance discussions to determine if length or depth of conversation, among other variables, relate to social-emotional outcomes for students.

There is an additional generalizability issue. This experiment was conducted with a single theater and a single show. It is important to note that while using a single theater and single show do strengthen the causal inference of the study because there is no need to control for possible differential effects of multiple shows, results may not generalize to other theaters or other shows. The show in the current study was specifically about perspective taking and experiencing the world through other people’s experiences. As such, we do not wish to imply that any live theater performance will impact change on students’ SEL, but rather that theater can be a useful mechanism to introduce SEL concepts and engage with related educational materials. Further research is needed to expand findings to a variety of productions, geographic locations, diversity of audiences, etc., to better understand the utility of live theater as a tool to improve SEL (Holochwost et al., Citation2021).

Conclusions

Given recent findings on the positive effects of watching theater on important prosocial factors in children and adults (Greene et al., Citation2018; Rathje et al., Citation2021), it is necessary to replicate these findings in different populations with different productions, and to investigate common educational interventions and practices that could moderate and strengthen effects. Though there was no main effect for the theater performance alone, the main effect of the Facilitated Discussion and the several moderation effects involving both the Facilitated Discussion and the Performance Guide show that when paired with educational pre- and post-performance experiences, middle school students’ social-emotional skills can be positively impacted through a single live theater performance. The results of students’ in-show Engagement suggest all preparation and experiences measured (e.g., prior or current Theater Experience) relate to higher levels of in-show Engagement. Furthermore, higher levels of in-show Engagement significantly predicted higher levels of all four of the outcome variables. These findings indicate that in-show Engagement can be boosted, and in turn, positively impact students’ social-emotional skills at a live theatrical performance.

Acknowledgements

We’d like to thank The Kennedy Center Education Division, Kennedy Center Research & Evaluation part time workers and data collectors, participating school districts, and all of the teachers and students who participated in the study for their contributions to this work.

Data Availability Statement

Due to MOAs with the participating school districts, research data are not available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adrian, J. E., Clemente, R. A., Villanueva, L., & Rieffe, C. (2005). Parent–child picture-book reading, mothers' mental state language and children's theory of mind. Journal of Child Language, 32(3), 673–686.

- Aram, D., & Aviram, S. (2009). Mothers' storybook reading and kindergartners' socioemotional and literacy development. Reading Psychology, 30(2), 175–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702710802275348

- Bal, P. M., & Veltkamp, M. (2013). How does fiction reading influence empathy? An experimental investigation on the role of emotional transportation. PloS One, 8(1), e55341. [PMC][23383160

- Barr, J. J., & Higgins-D'Alessandro, A. (2007). Adolescent empathy and prosocial behavior in the multidimensional context of school culture. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 168(3), 231–250.

- Beales, J. N., & Zemel, B. (1990). The effects of high school drama on social maturity. School Counselor, 38, 46–51.

- Black, J. E., Barnes, J. L., Oatley, K., Tamir, D. I., Dodell-Feder, D., Richter, T., & Mar, R. A. (2021). Stories and their role in social cognition. In D. Kuiken & A. M. Jacobs (Eds.), Handbook of Empirical Literary Studies (p. 229). De Gruyter.

- Blackwell, C. (2019, May 15) Giving Voice to Young Audiences: Evaluating the Intrinsic Impact of Live Performance. TYA Today, Spring 2019.

- Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives. Vol. 1: Cognitive domain (pp. 20–24). McKay.

- Bowie, B. H. (2010). Emotion regulation related to children's future externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23(2), 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00226.x[PMC] [20500623

- Burchinal, M., Foster, T. J., Bezdek, K. G., Bratsch-Hines, M., Blair, C., Vernon-Feagans, L., & Family Life Project Investigators. (2020). School-entry skills predicting school-age academic and social–emotional trajectories. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 51, 67–80.

- Campos, J. J., Frankel, C. B., & Camras, L. (2004). On the nature of emotion regulation. Child Development, 75(2), 377–394.

- Carter, C. S. (2005). Effects of formal dance training and education on student performance, perceived wellness, and self-concept in high school students. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A, 65, 2906.

- CASEL. (2020). SEL: What Are the Core Competence Areas and Where are they Promoted? https://casel.org/sel-framework/.

- Catterall, J. S. (2007). Enhancing peer conflict resolution skills through drama: An experimental study. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 12(2), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569780701321013

- Christenson, S. L., Reschly, A. L., & Wylie, C. (Eds.). (2012). Handbook of research on student engagement. Springer.

- Cuff, B. M., Brown, S. J., Taylor, L., & Howat, D. J. (2016). Empathy: A review of the concept. Emotion Review, 8(2), 144–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073914558466

- Curby, T. W., Brown, C. A., Bassett, H. H., & Denham, S. A. (2015). Associations between preschoolers' social–emotional competence and preliteracy skills. Infant and Child Development, 24(5), 549–570. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.1899

- Davis, M. H. (1983). The effects of dispositional empathy on emotional reactions and helping: A multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality, 51(2), 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1983.tb00860.x

- DeBettignies, B. H., & Goldstein, T. R. (2020). Improvisational theater classes improve self-concept. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 14(4), 451–461. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000260

- Decety, J., & Jackson, P. L. (2004). The functional architecture of human empathy. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews, 3(2), 71–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534582304267187

- Degé, F., Wehrum, S., Stark, R., Schwarzer, G. (2009). Music training, cognitive abilities and self-concept of ability in children. Proceedings of the 7th Triennial Conference of European Society for the Cognitive Sciences of Music,.

- Denham, S. A., Blair, K. A., DeMulder, E., Levitas, J., Sawyer, K., Auerbach–Major, S., & Queenan, P. (2003). Preschool emotional competence: Pathway to social competence? Child Development, 74(1), 238–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00533

- Denham, S. A., McKinley, M., Couchoud, E. A., & Holt, R. (1990). Emotional and behavioral predictors of preschool peer ratings. Child Development, 61(4), 1145–1152.

- Diazgranados, S., Selman, R. L., & Dionne, M. (2016). Acts of social perspective taking: A functional construct and the validation of a performance measure for early adolescents. Social Development, 25(3), 572–601. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12157

- DICE Consortium. (2010). The DICE has been cast. Research findings and recommendations on educational theatre and drama.

- Djikic, M., Oatley, K., & Moldoveanu, M. C. (2013). Reading other minds: Effects of literature on empathy. Scientific Study of Literature, 3(1), 28–47. https://doi.org/10.1075/ssol.3.1.06dji

- Domitrovich, C. E., Durlak, J. A., Staley, K. C., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Social‐emotional competence: An essential factor for promoting positive adjustment and reducing risk in school children. Child Development, 88(2), 408–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12739

- Donelan, K., & Sallis, R. (2013). The education landscape: Building engaged theatre-goers. In J. O'Toole, R.-J. Adams, M. Anderson, B. Burton, & R. Ewing (Eds.), Young audiences, theatre and the cultural conversation (pp. 65–82). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7609-8_5

- Eisenberg, N., & Zhou, Q. (2000). Regulation from a developmental perspective. Psychological Inquiry, 11(3), 166–171.

- Elliott, R., Bohart, A. C., Watson, J. C., & Greenberg, L. S. (2011). Empathy. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022187

- Elpus, K. (2013). Arts education and positive youth development: Cognitive, behavioral, and social outcomes of adolescents who study the arts. National Endowment for the Arts.

- Farrington, C. A., Maurer, J., Aska McBride, R. R., Nagaoka, J., Puller, J. S., Shewfelt, S., … Wright, L. (2019). Arts education and social-emotional learning outcomes among K-12 students. Sign, 773, 702–3364.

- Fitzgibbon, E. (1993). Planting the seeds: The nature and function of pre-show workshops in theatre-in-education practice. Drama/Theatre Teacher, 6(1), 22–26.

- Garner, P. W., & Waajid, B. (2008). The associations of emotion knowledge and teacher–child relationships to preschool children's school-related developmental competence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 29(2), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2007.12.001

- Gehlbach, H. (2004a). A new perspective on perspective taking: A multidimensional approach to conceptualizing an aptitude. Educational Psychology Review, 16(3), 207–234.

- Gehlbach, H. (2004b). Social perspective taking: A facilitating aptitude for conflict resolution, historical empathy, and social studies achievement. Theory & Research in Social Education, 32(1), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2004.10473242

- Gehlbach, H., Brinkworth, M. E., & Wang, M. T. (2012a). The social perspective taking process: What motivates individuals to take another’s perspective? Teachers College Record, 114(1), 1–29.

- Gehlbach, H., Marietta, G., King, A. M., Karutz, C., Bailenson, J. N., & Dede, C. (2015). Many ways to walk a mile in another’s moccasins: Type of social perspective taking and its effect on negotiation outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior, 52, 523–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.035

- Gehlbach, H., Young, L. V., & Roan, L. K. (2012b). Teaching social perspective taking: How educators might learn from the Army. Educational Psychology, 32(3), 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2011.652807

- Gerdes, K. E., Segal, E. A., & Lietz, C. A. (2010). Conceptualising and measuring empathy. British Journal of Social Work, 40(7), 2326–2343. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcq048

- Glass, D., Begle, A. K. S., Hallaert, J. M. (2020, December 18). Factors that optimize engagement for diverse learners at arts performances for young audiences. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/2rcwq

- Gleason, K. A., Jensen-Campbell, L. A., & Ickes, W. (2009). The role of empathic accuracy in adolescents' peer relations and adjustment. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(8), 997–1011. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209336605

- Goldstein, T. R., Lerner, M. D., & Winner, E. (2017). The arts as a venue for developmental science: Realizing a latent opportunity. Child Development, 88(5), 1505–1512. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12884

- Goldstein, T. R., & Winner, E. (2012). Enhancing empathy and theory of mind. Journal of Cognition and Development, 13(1), 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/15248372.2011.573514

- Gourgey, A. F. (1985). The impact of an improvisational dramatics program on student attitudes and achievement. Children's Theatre Review, 34, 9–14.

- Greene, J. P., Erickson, H. H., Watson, A. R., & Beck, M. I. (2018). The play’s the thing: Experimentally examining the social and cognitive effects of school field trips to live theater performances. Educational Researcher, 47(4), 246–254. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X18761034

- Greene, J. P., Kisida, B., & Bowen, D. (2014). The educational value of field trips. Education Next, 15(1), 78–86.

- Harper, S. R., & Quaye, S. J., (Eds.). (2009). Student engagement in higher education: Theoretical perspectives and practical approaches for diverse populations. Routledge.

- Hedges, L. V. (1981). Distribution theory for Glass's estimator of effect size and related estimators. Journal of Educational Statistics, 6(2), 107–128. https://doi.org/10.3102/10769986006002107

- Holochwost, S. J., Goldstein, T. R., & Wolf, D. P. (2021). Delineating the benefits of arts education for children’s socioemotional development. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 624712. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.624712

- Holochwost, S. J., Wolf, D. P., Fisher, K. R., & O’Grady, K. (2017). The socioemotional benefits of the arts: A new mandate for arts education. William Penn Foundation.

- Izard, C., Fine, S., Schultz, D., Mostow, A., Ackerman, B., & Youngstrom, E. (2001). Emotion knowledge as a predictor of social behavior and academic competence in children at risk. Psychological Science, 12(1), 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00304

- Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Tjosvold, D. (2000). Constructive controversy: The value of intellectual opposition. In M. Deutsch & P. T. Coleman (Eds.), The handbook of conflict resolution: Theory and practice (pp. 65–85). Jossey-Bass.

- Jolliffe, D., & Farrington, D. P. (2006). Development and validation of the Basic Empathy Scale. Journal of Adolescence, 29(4), 589–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.08.010

- Kalpidou, M. D., Power, T. G., Cherry, K. E., & Gottfried, N. W. (2004). Regulation of emotion and behavior among 3-and 5-year-olds. The Journal of General Psychology, 131(2), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.3200/GENP.131.2.159-180

- Kang, S. H. (2016). Spaced repetition promotes efficient and effective learning: Policy implications for instruction. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732215624708

- Kidd, D. C., & Castano, E. (2013). Reading literary fiction improves theory of mind. Science, 342(6156), 377–380. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1239918

- Lee, S. O. (2006). The effects of dance education on self-concept formation of high school girl students. Korean Association of Arts Education, 4, 55–62.

- Lee, B. K., Patall, E. A., Cawthon, S. W., & Steingut, R. R. (2015). The effect of drama-based pedagogy on preK–16 outcomes: A meta-analysis of research from 1985 to 2012. Review of Educational Research, 85(1), 3–49. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654314540477

- Mar, R. A. (2018). Stories and the promotion of social cognition. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(4), 257–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417749654

- Mar, R. A., Tackett, J. L., & Moore, C. (2010). Exposure to media and theory-of-mind development in preschoolers. Cognitive Development, 25(1), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2009.11.002

- Martin, J., Sokol, B. W., & Elfers, T. (2008). Taking and coordinating perspectives: From prereflective interactivity, through reflective intersubjectivity, to metareflective sociality. Human Development, 51(5-6), 294–317. https://doi.org/10.1159/000170892

- Mcclelland, M., Tominey, S., Schmitt, S., & Duncan, R. (2017). SEL interventions in early childhood. The Future of Children, 27(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2017.0002

- Merrell, K. W., Juskelis, M. P., Tran, O. K., & Buchanan, R. (2008). Social and emotional learning in the classroom: Evaluation of strong kids and strong teens on students' social-emotional knowledge and symptoms. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 24(2), 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377900802089981

- Panero, M. E., Weisberg, D. S., Black, J., Goldstein, T. R., Barnes, J. L., Brownell, H., & Winner, E. (2016). Does reading a single passage of literary fiction really improve theory of mind? An attempt at replication. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111(5), e46.

- Rathje, S., Hackel, L., & Zaki, J. (2021). Attending live theatre improves empathy, changes attitudes, and leads to pro-social behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 95, 104138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2021.104138

- Reason, M. (2010). The Young Audience: Exploring and Enhancing Children's Experiences of Theatre. Trentham Books.

- Samur, D., Tops, M., & Koole, S. L. (2018). Does a single session of reading literary fiction prime enhanced mentalising performance? Four replication experiments of Kidd and Castano (2013). Cognition & Emotion, 32(1), 130–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2017.1279591

- Saville, K. (2011). Strategies for using repetition as a powerful teaching tool. Music Educators Journal, 98(1), 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0027432111414432

- Selman, R. L. (1975). Level of social perspective taking and the development of empathy in children: Speculations from a Social‐Cognitive viewpoint. Journal of Moral Education, 5(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305724750050105

- Weissberg, R. P., & Cascarino, J. (2013). Academic learning + social-emotional learning = national priority. Phi Delta Kappan, 95(2), 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172171309500203

- What Works Clearinghouse. (2020). What Works Clearinghouse standards handbook, version 4.1. Institute of Education Sciences.

- Woods-Robinson, J. (2018). Audience engagement in theatre for young audiences: Teaching artistry to cultivate tomorrow's theatre-goers [Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004–2019], 5861. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5861

Appendix A

Performance Guide

Appendix B

Facilitated Discussion Sample Questions/Script

Priming the conversation: “As you watch the play, I want you to think about who YOU would rather be, Kid Prince or Pablo? And why?”

Invitation to Discussion: “Who remembers the question I asked you to think about before the show? How many of you would choose to be Kid Prince? Show of hands. How many of you would choose to be Pablo? Show of hands. Ok, who wants to share why they chose the person they chose?”

Analysis: Facilitator chooses students to explain their choices and as they give answers, the facilitator brings relevant points from the themes of the show and other factors at play (e.g., oppression, privilege, Hip-Hop, power and resources, etc.).

Reflection: Facilitator asks students if they’d still choose to be the same person or if they would change their answer after seeing the performance, then chooses students to respond. Facilitator concludes with “Thank you for sharing your ideas with me today. Now “Kid Prince and Pablo” is all yours to talk about, share, and think about with your classmates, friends and family.”