Abstract

Feelings of acceptance within school communities can promote positive psychological outcomes. Despite occurring outside of the classroom, youth who engage in extracurricular activities typically report greater school belonging. Accordingly, we examined the longitudinal effect of extracurricular activities on school belonging and depressed mood in a nationally representative, Australian sample of adolescents (N = 3,850, Mage = 12.41) followed for four years. A random-intercept cross-lagged panel model revealed extracurricular activity participation at Time 1 predicted higher school belonging two years later. In turn, higher school belonging reinforced positive mental health outcomes, by predicting within-person decreases in depressed mood. Further, the direct and indirect effect of extracurricular activities were moderated by community-level socioeconomic status. Participants residing in low socioeconomic status communities garnered the greatest benefit from participating in activities, despite having the lowest levels of participation. Our data highlight how structured leisure time pursuits can promote wellbeing, especially within more disadvantaged communities.

Adolescence is one of the most pivotal developmental periods when there is considerable emphasis placed on attaining formal education. Young people are expected to spend a substantial amount of time in classrooms, completing homework, interacting with teachers and peers, and preparing for their life after school. It is therefore unsurprising that what occurs in a schooling context can have profound implications for adolescents’ mental health (Kidger et al., Citation2012). With a growing emphasis on the second decade of life, efforts to reduce the prevalence of mental health disorders during adolescence should be a highly resourced priority for policy makers and school administrators (Department of Education, Citation2023). To aid these efforts, the current study specifically focuses on extracurricular activity participation as a protective factor that may increase young people’s subjective sense of belonging to ones’ school (Allen et al., Citation2018), and lessen their reports of depressed mood across adolescence (Eccles & Barber, Citation1999; Mahoney et al., Citation2005; Oberle et al., Citation2019).

Empirical evidence and conceptual frameworks have purported that adolescent engagement in extracurricular activities fosters positive youth development and provides an opportunity to increase school belonging and improve mental health outcomes (e.g. Eccles et al., Citation2003; Lareau, Citation2003). Extracurricular activities allow young people to explore their interests in supervised and structured settings during their leisure time. The interests that adolescents can take up are varied and may include athletic, academic, vocational, artistic, and other pursuits (Mahoney et al., Citation2005). Regardless of the nature of the activity, participation in any of these varied forms of structured activities are known to enrich the lives of adolescents (Farb & Matjasko, Citation2012). Although past research has established the psychological and social benefits of activity participation, who benefits from activity participation has been less attended to in the literature. This omission is notable, given recent calls amongst scholars to acknowledge how specific experiences at specific times will impact individuals in specific ways (known as the specificity principle, Bornstein, Citation2019; Lerner & Bornstein, Citation2021). Accordingly, in the current study we compare the long-term effects of activity participation on school belonging and depressed mood across communities and families, with varying socioeconomic statuses, financial hardship, and remoteness to identify protective factors that may be more or less important across the population.

Extracurricular activities, school belonging, and mental health

Our investigation is grounded by Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979, Citation1986, Citation1993). Typically presented as a series of concentric circles, this framework purports that youth development, both within and across time, is fostered through reciprocal interactions across intersecting social and environmental contexts. The microsystem is the most centrally located sphere, encapsulating all interpersonal interactions and experiences young people engage in within their immediate surroundings. As a social context, extracurricular activity settings can be a conduit linking adolescents with like-minded peers, coaches, and mentors; and are therefore typically considered to reside within the microsystem of the developing adolescent (Simpkins et al., Citation2012). Yet, we understand that participation in activities has wider benefits, both beyond this immediate context, and for the young person later in their development. Most notably, decades of research now confirm that adolescents who participate in extracurricular activities, for example, report better school-based outcomes than non-participants (Farb & Matjasko, Citation2012).

Specific empirical findings illustrate the benefits of activity participation with negative relationships extending to school disengagement (Neely & Vaquera, Citation2017), conduct issues (Aumètre & Poulin, Citation2018), and educational attainment (Lleras, Citation2008), alongside positive relationships with aspirations (Denault & Poulin, Citation2009; Rose-Krasnor et al., Citation2006), and performance (Shulruf, Citation2010). Of central importance to the current study, robust cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have found participating in extracurricular activities predicts higher concurrent and future levels of school belonging across adolescence (e.g. Blomfield & Barber, Citation2010; Dotterer et al., Citation2007; Eccles et al., Citation2003; Martinez et al., Citation2016; McNeely et al., Citation2002; Rees et al., Citation1990; Waters et al., Citation2010).

As the conduit between microsystems, the mesosystem provides a framework to understand how experiences within activities can impact schooling outcomes. Young people are actively involved in shaping their social environment. What they learn in one environment can be applied in distinct settings. Similarly, repeated messaging and experiences can be reinforced across contexts. With regards to activity participation, the experiences related to teamwork, sharing, emotional regulation, open communication, and self-expression can build social competencies and develop a sense of meaning (e.g. Berger et al., Citation2020; Fredricks et al., Citation2002; Schaefer et al., Citation2011). The competences that are then developed and accumulated within the individual as experienced within, and across, the micro- and meso-systems can then be carried forward as internal strengths (or coping resources) used to foster greater adaptation when faced with challenges and adversity later in development. By articulating the interdependencies between adolescents’ microsystems, the mesosystem outlines how the social competencies and relationships provided by activity participation can subsequently influence how individuals fare in other contexts (such as in their schooling environment) and how they stave off emotional problems later in life (e.g. von Salisch et al., 2013). In this way, not only does Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory provide theoretical grounding for our current investigation, but it also helps us to better understand the implications of our findings to adolescent development, more broadly.

As indicated above, school belonging, in turn, may drive functional mental health outcomes. Adolescents spend a large part of their waking hours at school, and school experiences have the power to influence mental health outcomes (Baumeister & Robson, Citation2021; Diendorfer et al., Citation2021; Shochet et al., Citation2006). The extant literature supports this claim, with a greater sense of school belonging as a positive predictor of adolescent mental health and wellbeing outcomes, including increased subjective wellbeing, and reduced loneliness, negative affect, conduct problems, depression, and anxiety (Arslan, Citation2021; Barber & Schluterman, Citation2008; Jose et al., Citation2012; Loukas et al., Citation2009; Shochet et al., Citation2006). The links between school belonging and mental health outcomes are partially attributable to peer and teacher interactions (Cemalcilar, Citation2010; Goodenow & Grady, Citation1993; Hamm & Faircloth, Citation2005), that are likely to influence self-esteem, a sense that one matters, and intrinsic motivations that promote psychological health (Arslan, Citation2021; Barber & Schluterman, Citation2008).

In the current study, we build off the extensive literature by specifically focusing on the relationship between extracurricular activity breadth, school belonging, and the psychological outcome of depressed mood. It is argued that extracurricular activity breadth will shape a young person’s ability to form friendships, navigate complex social structures in the school yard, and interact with teachers. Breadth is defined as the total number of distinct activity types (e.g. team sport, academic clubs, etc.) adolescents engage in during a specified period (Bohnert et al., Citation2010; Eccles & Barber, Citation1999) regardless of whether these are organized in school or the community. Each activity type provides adolescents with a unique social network and opportunities to hone skills that may be exclusive to a single activity. Greater extracurricular commitments also provide novel challenges for adolescents who are forced to manage their time, grow their autonomy, and balance competing demands (Bohnert et al., Citation2010). The combined influence of expanding social ties and developing soft skills should therefore promote greater school belonging given these are transferrable skills that can be applied in other domains. With a greater sense of school belonging, activity participants are in turn more likely to report lower levels of depressed mood. We test this proposition while also comparing the effect of activity breadth among young people who experience a variety of structural inequities, to ascertain if and how indicators of disadvantage may moderate any effect of extracurricular activity participation. In doing so, we acknowledge that activities do not occur in a vacuum. On the contrary, the beneficial experiences in extracurricular activities occur in the backdrop of adolescents’ existing developmental assets and resources.

The compensation hypothesis: Greater benefits for more disadvantaged youth

It is well known that structural inequities, including socioeconomic disadvantage, regional living (akin to the rural and urban distinction used in other nations), and household financial strain can limit adolescents’ access to developmental assets, ultimately manifesting in educational and developmental disadvantages (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, Citation2000; Leventhal & Dupéré, Citation2019). These factors represent distinct systems within the bioecological model. As an important contextual factor that only indirectly influences young people (Masarik & Conger, Citation2017), family financial hardship is situated within the exosystem. Community socioeconomic status and region would be represented on the macrosystem, reflecting how extended social structures alter life course options and trajectories of young people (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1993). Central to his scientific contribution, Bronfenbrenner argued that the processes that occur within the centrally located spheres of influence are shaped by more distal contextual factors (Tudge et al., Citation2009). In the current study, we apply this reasoning by testing if the benefits of activity participation (situated in the microsystem) are most notable in the context of common markers of disadvantage.

Stated broadly, the compensation hypothesis purports that the developmental assets inherent in extracurricular activities will be more salient among young people with fewer opportunities elsewhere. Accordingly, extracurricular activity participation may mitigate inequities in developmental outcomes (Downey & Condron, Citation2016; also referred to as a resilience perspective; Steinberg & Simon, Citation2019; and differential effectiveness, Roth & Brooks-Gunn, Citation2016). In support of this hypothesis, a growing body of evidence suggests structurally disadvantaged youth derive greater benefits from activity participation compared to advantaged youth, who are more likely to exhibit positive developmental outcomes regardless of participation status.

Support for the compensation hypothesis has now been reported across several indicators of adjustment and source of disadvantage. Comparisons across community-level socioeconomic status have revealed that participation in extracurricular activities was associated with lower delinquency (O’Donnell & Barber, Citation2021), fewer emotional problems (O’Donnell et al., Citation2020), and greater self-worth (Blomfield & Barber, Citation2011), but only for adolescents in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods. Youth residing in communities with high socioeconomic status reported positive outcomes regardless of participation. Similarly, the compensation hypothesis was supported in studies on academic performance (Crosnoe et al., Citation2015; Morris, Citation2015; Ren et al., Citation2021) and risk-taking (O’Donnell et al., Citation2023) when household indicators of socioeconomic status and financial deprivation were used. Finally, extracurricular activity participation predicted greater school functioning and academic performance among students in regional areas, while participants in metropolitan areas reported positive outcomes regardless of participation (O’Donnell et al., Citation2022).

From these results, it is asserted that the positive developmental experiences provided in organized activities are more salient for disadvantaged youth, who have fewer opportunities for enriching experiences in other contexts where they live, learn, and play. In the current study, we extend this basic principle, exploring family financial hardship, community socioeconomic status, and remoteness as moderators of the relationship between extracurricular activity breadth and adolescent school belonging and depressed mood. These three structural barriers to youth social participation and wellbeing were selected due to the unique (albeit overlapping) pressures they apply on youth development.

Community factors are likely to restrict access to enriching public spaces, increase exposure to risk-taking others, reduce feelings of safety, and alter the social and cultural norms that become embedded across time. Household disadvantages can introduce strained child-caregiver relationships, increase personal stress, and reduce access to paid services (Masarik & Conger, Citation2017; Ou et al., Citation2017). Bioecological models of human development argue that more proximal interactions drive outcomes across the life course (Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, Citation1994) suggesting that household disadvantages in the exosystem may have a larger effect on development. However, distal community and social factors are known to shape these more proximal interactions. With few attempts to directly test the compensatory effects of extracurricular activities for different structural disadvantages (c.f., Steinberg & Simon, Citation2019; Urban et al., Citation2009), the current study may shed new light on who derives the greatest schooling and mental health benefits from activity participation.

The current study

Taken together, the extant literature suggests adolescents who participate in extracurricular activities should report higher levels of school belonging and reduced depressed mood. In the current study, we aim to extend this work by considering if adolescents who experience structural inequities derive greater benefits from participation, relative to their more advantaged peers. In accordance with the aims of the current study, several hypotheses were tested in a nationally representative, longitudinal study of Australian youth with biennial data collection from the ages of 12 and 13 through to 16 and 17. First, we predicted that greater participation in extracurricular activities at age 12/13 would predict higher levels of school belonging across adolescence. Second, we hypothesized that this effect would longitudinally and indirectly predict depressed mood. Third, we anticipated the presence of a significant conditional indirect effect, whereby different indicators of disadvantage may moderate the indirect link between extracurricular activity participation and depressed mood. Three distinct indicators of disadvantage were concurrently tested in the current study: Community socioeconomic status, financial strain, and remoteness.

The effects we have hypothesized fundamentally relate to within-person processes, whereby we anticipate intraindividual changes in school belonging and depressed mood that may be attributable to activity participation. However, adolescents who engage in extracurricular activities are typically academically orientated and are otherwise socially competent (Larson, Citation2000). As such, analytical techniques that account for established between-person differences were employed to ensure that any measured impacts of activity participation on positive development do not simply reflect the variety of preexisting advantages associated with activity participation.

Method

Openness and transparency

The current study used data from the publicly available Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC). Interested readers may find an online repository of all research output from the LSAC study with accompanying information about data access, guidelines, and measures (https://growingupinaustralia.gov.au/). The data can be accessed by qualified researchers following an online application (Department of Social Services; Australian Institute of Family Studies; Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2022). All syntax, analysis outputs, and a series of sensitivity analyses are available online (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/TB4R8). Our project was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Flinders University.

The authors of the current study have previously published two related studies using the same sample of LSAC participants. The first study examined whether the longitudinal relationship between extracurricular activity participation and academic outcomes (school functioning, academic expectations, and performance) were conditional on regional living (O’Donnell et al., Citation2022). The second study considered whether financial hardship alters the relationship between extracurricular activity participation and both affiliations with risk-taking peers and engagement in risk-taking behaviors (O’Donnell et al., Citation2023). Although related, the results in the current study focus on mental health outcomes and model the compensatory effect of multiple structural inequities simultaneously. For transparency we have explored within and between-person effects in the focal six psychological constructs in these studies (school belonging, depressed mood, school functioning [a pediatric quality of life index], risk-taking, risk-taking peers, and educational expectations). The results across each published work and those reported below were all replicated.

Participants and procedure

Data from the LSAC K cohort were used in the current study (Gray & Smart, Citation2008). The LSAC commenced in 2004 with the recruitment of 4- and 5-year-olds who were selected from a nationally representative, Government-owned database (Sanson et al., Citation2002). The current study utilizes the data from the 5th wave of data collection as the initial time-point, which included 3,850 responses from 12 and 13-year-olds (M = 12.41, SD = 0.49). There was an approximately even split between males (51.1%) and females (48.9%) sampled, and the majority were born in Australia (96.1%) and spoke English at home (91.7%). The 6th (N = 3,526) and 7th (N = 3,048) waves of data collection occurred every second year and were also used in the current study, allowing us to longitudinally model changes in school belonging across the early and middle years of adolescence. Data were collected with a combination of in-home interviews and computer-assisted self-interviews with both parents/carers and young people themselves.

Measures

School belonging

The mean of a 12-item version of the Psychological Sense of School Membership scale (Goodenow, Citation1993) was introduced to the LSAC in the 5th wave and was used to measure school belonging in this study. Participants indicated the extent to which they feel accepted by teachers (e.g. Teachers are interested in me) and more generally within their schooling community (e.g. I can be myself at school). Responses were provided on a 5-point scale (1 = Not at all true to 5 = Completely true). The original scale has been widely used in research (You et al., Citation2011) and was internally consistent in the current study (Cronbach’s alphas are provided in ).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s Alpha, and Bivariate Correlations between extracurricular activity participation, socioeconomic status, school belonging, and peer connectedness.

Depressed mood

Thirteen items from Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ, Angold et al., Citation1995) were used to measure depressed mood. Participants indicated the extent to which they experienced mood disturbances and negative feelings during the previous two weeks (e.g. “I thought I could never be as good as other kids,” “I was very restless”). Responses were collected on a three-point scale and summed to form a total depressed mood score (1 = Not True, 2 = Sometimes, 3 = True).

Extracurricular activity participation

Adolescents were asked to indicate if they had participated in extracurricular activities in the previous year at the first time point. The participants who had engaged in extracurricular activities (89.8%) were then asked to nominate the activities engaged in using a list of 9 distinct activity categories (Individual Sport, Team Sport, Band, Drama, Art/Craft, Student Council, School Newspaper, Community Services, and Club/Society). Responses were summed to form a breadth indicator ranging from 0 (no activities) through to 9.

Community socioeconomic status

The Index of Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage (IRSD) was used to assess community socioeconomic status (ABS, 2016). Each geographic region in Australia (e.g. a neighborhood, suburb or postcode area) has a score comprised of a range of socioeconomic disadvantages (e.g. proportion of people with low income, single parent households, households without internet) based upon the Australian Census (Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS; Citation2016a). The scale is a continuum normalized so that the average Australian community would have a score of 1,000 (SD = 100), with higher scores indicating low levels of disadvantage. As large differences in raw scores across variables can impact model convergence, the index was recoded to have a mean of 1.00 (SD = 0.10) in the final model.

Financial hardship

The primary caregiver was provided with a series of behaviors that may stem from financial strain and difficulties paying bills (e.g. Could not pay the mortgage or rent payments on time) and asked whether they had occurred in the last year. Responses were summed (1 = Yes, 0 = No) to form a total score in line with previous research (e.g. O’Donnell et al., Citation2023).

Remoteness

The home address of each participant was linked to The Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) Remoteness Structure, as compiled by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS, Citation2016b). Each community in Australia is classified from a Major City (0) through to Very Remote (4) based upon the road distance from the geographic area to the nearest urban centers in Australia where services are available. As a purely geographic indicator, the remoteness index is distinct from socioeconomic considerations.

Analytical strategy

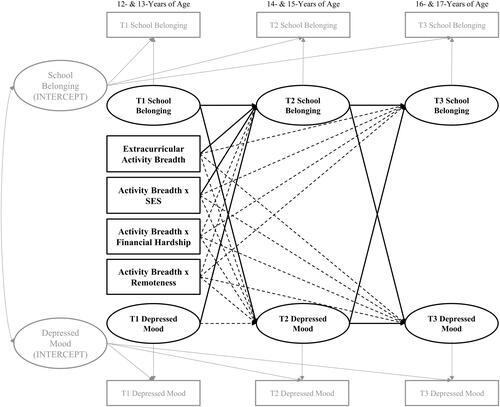

Following the computation and examination of bivariate correlations (), a random-intercept autoregressive cross-lagged panel model (RI-CLPM; Hamaker et al., Citation2015) was estimated in Mplus (v8.4 Muthén & Muthén 1998–Citation2017). The random intercept partitions between-person variance (i.e. trait like consistency across the duration of the study) from the longitudinal indicators, allowing the estimation of within-person stability in the autoregressive parameters and within-person change in the cross-lagged coefficients (Hamaker et al., Citation2015; Usami et al., Citation2019). Of particular interest, cross-lagged coefficients were calculated to explore the dynamic relationships between school belonging and depressed mood over time (). In RI-CLPMs, significant cross-lagged effects indicate that within-person deviations from the participants’ stable levels (i.e. ‘average’ level) of one construct at a given point in time precede a marked fluctuation from participants’ stable levels in another construct, two years later. Contemporaneous residual terms were covaried. To explore whether the effects of extracurricular activity breadth (T1) on subsequent outcomes (T2) were moderated by structural inequities, activity participation, community socioeconomic status, family financial hardship, and remoteness were entered into the model as predictors alongside three multiplicative interaction terms.

Table 2. Regression coefficients exploring the longitudinal relationship between structural inequities, extracurricular activity breadth, school belonging, and depressed mood.

Following the estimation of the conditional RI-CLPM (), indirect effects between extracurricular activity participation at T1 and depressed mood at T3 were computed, through higher school belonging (T2). This approach provides a sophisticated view of the dynamic temporal processes that unfold over time and provide information regarding the temporal ordering and comparative importance of constructs (Jose, Citation2013; Selig & Preacher, Citation2009).

Figure 1. The full RI-CLPM depicting the between- and within-person effects of school belonging and depressed mood across adolescence. Solid black lines denote significant pathways (p < .05), dashed lines denote non-significant pathways. Residuals, contemporaneous covariances, and covariates are omitted for parsimony.

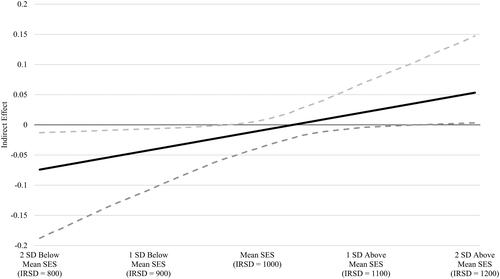

Next, we adapted Mplus syntax provided by Stride et al. (Citation2015) to compute an index of moderated mediation (Hayes, Citation2015) and conditional indirect effects (Mplus syntax is provided at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/TB4R8). In our model, these coefficients determined whether the strength of the indirect effects from extracurricular activity participation (T1) and depressed mood (T3) were conditional on community socioeconomic status, family financial hardships, or region. In line with the conventions of the Johnson-Neyman technique (Bauer & Curran, Citation2005), we plotted the strength of the indirect effect and corresponding 95% confidence intervals as a function of the moderator, if the interaction term was statistically significant. The indirect effect is said to be significant when the confidence intervals do not contain a zero. Indeed, the significance of all indirect pathways was evaluated using bias-corrected bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals using 5,000 bootstrapped samples for the unstandardized coefficients.

As with all longitudinal studies, attrition and missingness were evident in the LSAC study. Preliminary analyses suggested that the rate of missingness across the study’s duration was not missing completely at random (χ2(460) = 851.04, p < .001; Little, Citation1988). Indeed, the proportion of missing data in school belonging and depressed mood was significantly correlated with T1 financial hardships (r = .13, p < .001), community socioeconomic status (r = −0.11, p < .001) and activity breadth (r = −0.14, p < .001). Accordingly, our model was tested using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) to account for missing data. FIML estimates the model using all available information, assuming that the data is missing at random (Enders & Bandalos, Citation2001). In instances where data are not missing completely at random, such as the current study, FIML provides an unbiased approach to address missing data (Enders & Bandalos, Citation2001). Analyses were conducted using a sandwich estimator to account for non-independence of cases, with participants clustered by school.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations

The correlations () expectedly revealed significant associations between school belongingness and depressed mood across all three waves. Further, extracurricular activity breadth at T1 was associated with higher school belonging at T1-T3 and lower depressed mood at T1. Although remoteness was not consistently related to either school belonging or depressed mood, participants residing in higher socioeconomic status communities and in families with fewer financial hardships reported better outcomes across all three waves. Importantly, participants who resided in higher status and less remote communities and experienced fewer financial hardships were likely to participate in a greater number of activity types.

Random-intercept cross-lagged panel model

The association between school belonging and depressed mood

Trait-levels of school belonging, measured by the random intercepts were correlated with trait-like levels of depressed mood (β = −0.66, p < .001). This association suggests that individuals who reported higher levels of school belonging over the duration of the study similarly had lower levels of depressed mood across timepoints. However, there was also evidence of significant longitudinal effects. Within-person increases in school belonging preceded decreased depressed mood two years later. This effect was bi-directional, with increasing depressed mood lowering school belonging at the age of 14/15 and 16/17.

Extracurricular activity participation as a predictor of subsequent school belonging and depressed mood

Extracurricular activity breadth at the onset of adolescence was positively associated with within-person changes in school belonging two years later but was not directly related to depressed mood. Interestingly, there was no evidence of sleeper or lagged effects as activity breadth was not associated with either outcome at the third timepoint. Next, indirect effects were examined to explore how the proximal effects of participating in extracurricular activities can predict longer-term depressed mood. Greater extracurricular activity breadth at T1 was indirectly associated with lower depressed mood four years later via greater school belonging at T2 (b = −0.35, CI95% [-0.88 to −0.06], p < .05). Extracurricular activities therefore had a cascading effect on depressed mood due to their more proximal impact on school belonging.

Finally, we tested the premises of the compensation hypothesis by exploring the interaction between activity breadth and community socioeconomic status, family financial hardship, and remoteness. The only significant interaction term was comprised of activity breadth and community socioeconomic status, predicting T2 school belonging. To examine the impact of this interaction on the indirect effect, we computed the index of moderated mediation and determined that the significant indirect effect of extracurricular activity participation on depressed mood was conditional on community socioeconomic status (b = 0.32, CI95% [0.05 to .082], p < .05).

Subsequently, we probed the conditional indirect effect using the Johnson-Neyman method. Depicted in , the direction and strength of the indirect effect (y-axis) denotes the extent to which extracurricular breadth indirectly increases (positive) or decreases (negative) depressed mood 4 years later, via school belonging. We plotted the strength of this indirect effect at differing levels of community socioeconomic status presented on a continuous scale (x-axis, noting that only the mean and standard deviations were labelled). Bootstrapped and bias corrected confidence intervals determined if the strength of the indirect effects were significantly different than 0. Using this approach, we found that greater breadth indirectly predicted a decrease in depressed mood across 4 years, but only amongst adolescents residing in communities with indicators of socioeconomic status below the national mean (see the region of significance in ). In contrast, the indirect effect was not significant when participants resided in higher socioeconomic status communities (i.e. above the nationally normed mean, as depicted by the inclusion of 0 in the confidence internals in ). Accordingly, there is no evidence that participants who reside in more advantaged communities, who are significantly more likely to report low levels of depressed mood, derived additional benefits from broader engagement in extracurricular activities.

Figure 2. The Indirect Effect and 95% Confidence Intervals of Extracurricular Activities (12-13 years of age) on Depressed Mood (16-17 years of age) via School Belonging (14-15 Years of Age) depending upon Community Socioeconomic Status. Confidence intervals that do not contain zero (solid grey line) are statistically significant (p < .05).

Sensitivity analyses

A series of robustness checks and sensitivity analyses were conducted to ensure that our key findings are robust to different analytical choices. All sensitivity tests are provided in our online supplementary materials on OSF (linked above). First, we replicated our findings using a dichotomously coded financial hardship indicator (0 = No hardships, 1 = At least one hardship) to acknowledge few participants reported high levels of financial hardship. Second, we replicated our findings using a dichotomous indicator of region (0 = Major City, 1 = Outside a Major City). With few participants engaging in five (3.5%), six (1.2%), seven (0.6%), eight (0.2%), and nine (n = 2) activities, we replicated our findings after winsorizing the activity breadth variable in three ways; to have a maximum score of four, five, and six. To ensure our findings were robust to missing data choices, we also replicated our findings using multiple imputation as a means of data replacement (Hayes & Enders, Citation2023).

Subsequently, we were motivated to establish if our findings were contingent on how extracurricular activities were measured. Accordingly, we initially recoded the list of extracurricular activities to determine if participants engaged in sports (Individual Sport, Team Sport) or a non-sporting activity (Band, Drama, Art/Craft, Student Council, School Newspaper, Community Services, and Club/Society). In this analysis, participants were coded as participating (1) or not (0). Six interaction terms were entered into the RI-CLPM to determine if the direct or indirect effects of the two activity types on our outcomes were conditional upon the three moderator variables. We did not find any evidence of moderation. Next, we summed the activity types to create breadth for both sporting and non-sporting activity types. Similarly, six interaction terms were entered concurrently into the RI-CLPM. Our findings were replicated, with community socioeconomic status moderating the indirect effect of non-sporting activity breadth on depressed mood via school belonging. Although this may attest to the importance of non-sporting activities comparatively to sporting pursuits, it is noteworthy that the range for sporting (0 to 2) activities was greatly constrained relative to non-sporting activities (0 to 7) by the nature of the questions posed to participants. Accordingly, the significant interaction may simply reflect the effect of greater breadth.

Finally, a second set of activity questions asked parents to indicate the activity patterns of their adolescents across the previous week, including the number of days and hours spent participating. Although we determined that seasonal fluctuations in participation patterns limit the ecological validity of these indicators, we nevertheless added together the total number of days spent participating in activities and included this variable as a covariate. In doing so, we ensured our results reflected participation in a broader range of activities rather than simply time spent participating. Our findings were replicated with this additional covariate. Taken together, these sensitivity tests provide robust evidence that activity breadth contributes to increased school belonging and subsequent decreases in psychological distress, and that these effects are contingent upon community-level socioeconomic status.

Discussion

In the current study, we examined the longitudinal relationship between extracurricular activity breadth, school belonging, and depressed mood in a nationally representative sample of Australian adolescents. Activity breadth was only uniquely associated with changes in school belonging two years later, with little effect directly on depressed mood contrary to previous research (e.g. Fredricks & Eccles, Citation2008). That is not to say that organized activities did not positively contribute to mental health. Indeed, the results painted a more complex story. Adolescents who engaged in extracurricular activities subsequently reported decreased depressed mood, but only via school belonging. Our study further revealed important differences in the benefits of extracurricular activities for adolescents depending on the socioeconomic status of the suburb where they lived. Each of these key findings (discussed below) has important implications for promoting school belonging and improving mental health across socioeconomic statuses.

The bi-directional association between school belonging and depressed mood

Our longitudinal assessment of within-person change identified interdependencies between school belonging and depressed mood. School belonging can foster a sense of self, trust in others, emotion-regulation behaviors, and self-efficacy (Allen et al., Citation2021; Barber & Schluterman, Citation2008), which demonstrably decreases depressive symptoms over time. Likewise, escalating depressive symptomology not only degrades potential personal strengths and interpersonal resources, but it also increases the likelihood for greater loneliness, academic disengagement and potential school dropout (Diendorfer et al., Citation2021; Rapee et al., Citation2019). These outcomes can have cascading influences for further maladjustment and opportunities for inclusion into the future. Consequently, a two-folded approach targeting adolescent depression is recommended. At an individual level, we require greater dissemination and access to individual evidence-based psychotherapies that may help to reduce individual risk factors and predispositions for depression. This should occur along with school-based initiatives aiming to foster greater school connection and identification that may be particularly helpful for abating young people’s mental health symptoms (Baumeister & Robson, Citation2021; Jose et al., Citation2012). Importantly, our data demonstrated that efforts to foster connectedness at school do not necessarily need to occur within school grounds.

Extracurricular activities are social contexts that provide adolescents with scenarios and settings that build social competencies and provide opportunities to develop friendships (Fredricks & Simpkins, Citation2013). We hypothesized that extracurricular activity participation would predict school belonging. Our data supported this hypothesis, whereby participants who reported engaging in a broader range of activities had within-person increases in school belonging two years later. Similar to other studies that have employed RI-CLPMs (see Burns et al., Citation2020; Hamaker et al., Citation2015), the effect of extracurricular activities was small in magnitude. However, our effects were found over two-year time lags while controlling for important between-person differences.

Interestingly, we did not find a significant, direct association between extracurricular activity participation and depressed mood. Indeed, the indirect effect via school belonging exemplifies the intermediary nature of activities, connecting young people to enriching experiences that serve to improve their immediate social environment and improve their psychological welfare (Fredricks & Eccles, Citation2005). In this study, we demonstrated activities are an especially powerful conduit, helping adolescents form a sense of connection at school that reduces experiences of depression and distress. However, this finding cannot be extrapolated to all participants in our sample, as significant differences were observed across communities.

Socioeconomic status moderates the effect of extracurricular activities on school belonging and depressed mood

A growing body of evidence illustrates youth from socioeconomically disadvantaged communities derive greater psychological, social, and educational benefits from extracurricular activities relative to youth in more advantaged communities despite having the lowest levels of participation (e.g. O’Donnell & Barber, Citation2021). Our data broaden this emergent literature by demonstrating that the general pattern of discrepant outcomes across communities extends to school belonging and indirectly extends to depressed mood. Participants from socioeconomically disadvantaged communities who engaged in extracurricular activities reported significantly higher levels of school belonging two years later, contributing to lower depressed mood four years later. In contrast, adolescents who participated in a greater variety of extracurricular activities seemingly did not benefit from higher levels of school belonging and lower depressed mood when residing in moderate or high levels of socioeconomic status communities.

Importantly, we did not find a significant direct interaction between extracurricular activity participation and depressed mood. Socioeconomic status only moderated the relationship between activity participation and school belonging. This combination of findings provides some support for the conceptual premise of the developmental asset compensation hypothesis.

The developmental assets and resources inherent in extracurricular activities may be especially salient for adolescents in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities (Blomfield & Barber, Citation2011). Congruent with previous research (e.g. Li et al., Citation2020; Loft & Waldfogel, Citation2021), participants from higher socioeconomic status communities reported significantly higher school belonging relative to more disadvantaged youth, potentially due to provision of cultural capital, perceptions of safety, and comfort interacting with extrafamilial adults in the school system. The enriching social experiences intrinsically embedded in extracurricular activities then become more essential and protective in contexts of disadvantage, where youth are not consistently enveloped in developmentally protective surroundings (Blomfield & Barber, Citation2011; O’Donnell et al., Citation2020). In contrast, the developmental assets embedded in structured leisure pursuits may be less essential for adolescents who mature within an environment characterized by greater access to resources and a wider range of supportive connections that facilitate schooling success.

Notably, the compensatory effects of extracurricular activity breadth only emerged for community-level socioeconomic status. Although past research has established a compensatory effect of activity participation on academic and behavioral outcomes for young persons in regional areas and deprived households (e.g. O’Donnell et al., Citation2022), neither financial hardships nor remoteness moderated the link between activity breadth and our outcomes. Our theoretical positing stated that the developmental experiences inherent in activity participation may be especially salient in contexts and settings where similar experiences are not readily available to young people (Blomfield & Barber, Citation2011).

Community socioeconomic status and financial hardships are known (positive and negative, respectively) correlates of healthy development (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, Citation2000). Yet, they are quantitatively and qualitatively distinct. Financial hardship likely inhibits access to available resources and opportunities while community socioeconomic status likely inhibits the availability of these same resources and opportunities for everyone in a geographic area. Thus, community socioeconomic status may have a more widespread impact on developmental resources as even relatively affluent families may have less access to opportunity structures when they are not locally available. Taken further, the expansion of prosocial peer networks and extrafamilial relationships in activity settings (Fredricks & Eccles, Citation2005) may be especially salient across deprived communities where schools are likely to be under resourced and transmit lower expectations through teachers and parents (Thomson et al., Citation2017). In contrast, young people in deprived households may still reside in advantaged areas with public resources (e.g. libraries) and better performing schools. Although region may similarly restrict access to public resources, it is notable that remoteness was not predictive of any outcome suggesting there was no deficit to be compensated for with extracurricular activities.

Despite the need for more granularities in our investigations of the compensation hypothesis, the findings from this study are important for education policy. Adolescents in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities generally experience educational disadvantages, including lower school performance and greater rates of absenteeism, conduct issues, and dropouts (Cairns et al., Citation1989; Loft & Waldfogel, Citation2021; Sirin, Citation2005). These disadvantages manifest in long-term inequities in education, income, and well-being that extend into adulthood (Minh et al., Citation2021). Indeed, our data suggest school belonging can alleviate psychological distress. Provision of extracurricular activities for young people in disadvantaged communities may assist in addressing inequities in educational and psychological outcomes if opportunities to participate are available, affordable, and appealing.

The findings in this paper support other research which calls for greater support for young people to access extracurricular activities (e.g. Heath et al., Citation2022; McLaughlin et al., Citation1994). The urgency of this need is underlined by the highly unequal participation rates in extracurricular activities across communities reported in this paper. This observation is not unique to our study. In fact, data from the United States suggest that inequality of participation rates across socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged communities has widened since the turn of the twenty first century (Meier et al., Citation2018). This disparity likely reflects a culmination of family and community factors that disproportionately impact young people in disadvantaged communities. Fewer activities are typically offered, curbing young peoples’ knowledge of and capacity to pursue a broad range of interests (Stearns & Glennie, Citation2010). With fewer options, young peoples’ prolonged engagement in activities is also impeded because fewer attractive alternatives emerge when an adolescents’ current activity no longer meets their individual wants and needs (Modecki et al., Citation2018; O’Donnell & Barber, Citation2021).

Limitations and future research directions

The current study was a longitudinal study on a nationally representative sample of Australian youth, providing an opportunity to study the long-term, within-person effects of extracurricular activities on peer and school outcomes. Despite these notable strengths, the study also had some limitations. Although originally nationally representative, participants were more likely to attrit if experiencing financial hardship within their household or community. Our modeling approach accounted for these biases across the four years of data used in the current study but does not account for biases stemming from drop out during earlier phases of data collection.

A second limitation includes our limited understanding of what occurred during activity participation. In the current study, we observed within-person changes in extracurricular activity participants’ appraisal of their school belonging. From this, we theorized that the attributes and experiences provided during activity participation built social competencies. However, the experiences within activities can vary across activity types, organizers/coaches, co-participants, and features (Hansen et al., Citation2003). For example, young people report varying levels of prosocial peers, experiences of success, flow, goal setting, and parental pressure when participating (Blomfield & Barber, Citation2011; Drane & Barber, Citation2016; Dworkin et al., Citation2003; O’Donnell & Barber, Citation2018). There is a strong theoretical and empirical basis to claim activities enrich the social lives of young people (Eccles et al., Citation2003), but a more granular focus on participants’ lived experiences during activity participation may offer a nuanced view of the processes underpinning the positive effects. Future research should therefore directly ask participants about their experiences in activities (e.g. the Youth Experiences Survey, Hansen et al., Citation2003) to determine which activity characteristics build the most nurturing developmental context.

By only measuring activity breadth at the onset of adolescence (T1, 12- to 13-years-of-age), our study also does not capture the dynamic nature of extracurricular involvement across adolescence. Indeed, research shows that breadth typically decreases across secondary education (Modecki et al., Citation2018). Young people can reduce the breadth of their extracurricular commitments to specialize in a single venture (Wiersma, Citation2000), or drop out completely as their educational, social, or vocational pursuits become more important. Accordingly, our findings do not fully capture how trajectories of extracurricular engagement contribute to long-term outcomes across developmental stages.

Conclusion

Feelings of acceptance and respect by members of a schooling community are vital to the psychological welfare of adolescents. Yet, many students may not feel accepted, especially when they encounter structural disadvantages. In the current study, we provided further evidence that engaging in extracurricular activities may promote feelings of belonging. Specifically, we identified that participation in extracurricular activities by young people in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas predicts decreases in their depressed mood through the development of stronger school belonging. Our data highlight that those who benefit the most from structured leisure time pursuits are in the most disadvantaged communities who are likely to have least access to these pursuits. While not easy, efforts to increase activity participation in disadvantaged communities may produce new opportunities to bridge the divide in psychological outcomes across communities while young people are engaged in recreational tasks that spark their interests.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (24.2 KB)Acknowledgement

The research undertaken for this paper was supported by the Australian Research Council (Project DP190100247). We would also like to acknowledge comments from Cathy Thomson, Sabera Turkmani, and Fiona Brooks on previous versions of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Allen, K., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., & Waters, L. (2018). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-016-9389-8

- Allen, K.-A., Kern, M. L., Rozek, C. S., McInereney, D., & Slavich, G. M. (2021). Belonging: A review of conceptual issues, an integrative framework, and directions for future research. Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(1), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530.2021.1883409

- Angold, A., Costello, E. J., Messer, S. C., & Pickles, A. (1995). Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 5(4), 237–249.

- Arslan, G. (2021). School belongingness, well-being, and mental health among adolescents: Exploring the role of loneliness. Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(1), 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530.2021.1904499

- Aumètre, F., & Poulin, F. (2018). Academic and behavioral outcomes associated with organized activity participation trajectories during childhood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 54, 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2017.11.003

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2016a). Technical Paper: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA, ABS Catalogue No. 2033.0.55.001). https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/2033.0.55.001

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2016b). Technical Paper: Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS): Volume 5 - Remoteness Structure (ABS Catalogue No. 1270.0.55.005). https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/1270.0.55.005

- Barber, B. K., & Schluterman, J. M. (2008). Connectedness in the lives of children and adolescents: A call for greater conceptual clarity. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 43(3), 209–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.01.012

- Bauer, D. J., & Curran, P. J. (2005). Probing interactions in fixed and multilevel regression: Inferential and graphical techniques. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 40(3), 373–400. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr4003_5

- Baumeister, R. F., & Robson, D. A. (2021). Belongingness and the modern schoolchild: On loneliness, socioemotional health, self-esteem, evolutionary mismatch, online sociality, and the numbness of rejection. Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(1), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530.2021.1877573

- Berger, C., Deutsch, N., Cuadros, O., Franco, E., Rojas, M., Roux, G., & Sánchez, F. (2020). Adolescent peer processes in extracurricular activities: Identifying developmental opportunities. Children and Youth Services Review, 118, 105457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105457

- Blomfield, C. J., & Barber, B. L. (2011). Developmental experiences during extracurricular activities and Australian adolescents’ self-concept: Particularly important for youth from disadvantaged schools. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(5), 582–594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9563-0

- Blomfield, C., & Barber, B. (2010). Australian adolescents’ extracurricular activity participation and positive development: Is the relationship mediated by peer attributes? Australian Journal of Educational & Developmental Psychology, 10, 114–128.

- Bohnert, A., Fredricks, J., & Randall, E. (2010). Capturing unique dimensions of youth organized activity involvement: Theoretical and methodological considerations. Review of Educational Research, 80(4), 576–610. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654310364533

- Bornstein, M. H. (2019). Fostering optimal development and averting detrimental development: Prescriptions, proscriptions, and specificity. Applied Developmental Science, 23(4), 340–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.1421424

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments in nature and design. Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22(6), 723–742. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1993). The ecology of cognitive development: Research models and fugitive findings. In R. Wonziak & K. Fischer (Eds.), Development in context: Acting and thinking in specific environments (pp. 3–44). Erlbaum.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Ceci, S. J. (1994). Nature-nuture reconceptualized in developmental perspective: A bioecological model. Psychological Review, 101(4), 568–586. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.101.4.568

- Burns, R. A., Crisp, D. A., & Burns, R. B. (2020). Re-examining the reciprocal effects model of self-concept, self-efficacy, and academic achievement in a comparison of the Cross-Lagged Panel and Random-Intercept Cross-Lagged Panel frameworks. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(1), 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12265

- Cairns, R. B., Cairns, B. D., & Neckerman, H. J. (1989). Early school dropout: Configurations and determinants. Child Development, 60(6), 1437–1452. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb04015.x

- Cemalcilar, Z. (2010). Schools as socialisation contexts: Understanding the impact of school climate factors on students’ sense of school belonging. Applied Psychology, 59(2), 243–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2009.00389.x

- Crosnoe, R., Smith, C., & Leventhal, T. (2015). Family background, school-age trajectories of activity participation, and academic achievement at the start of high school. Applied Developmental Science, 19(3), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2014.983031

- Denault, A. S., & Poulin, F. (2009). Intensity and breadth of participation in organized activities during the adolescent years: Multiple associations with youth outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(9), 1199–1213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9437-5

- Department of Education. (2023). The Australian student wellbeing framework. Retrieved September 11, 2023, from https://www.education.gov.au/student-resilience-and-wellbeing/australian-student-wellbeing-framework

- Department of Social Services; Australian Institute of Family Studies; Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2022). Growing Up in Australia: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) Release 9.0 C2 (Waves 1-9C), https://doi.org/10.26193/QR4L6Q

- Diendorfer, T., Seidl, L., Mitic, M., Mittmann, G., Woodcock, K., & Schrank, B. (2021). Determinants of social connectedness in children and early adolescents with mental disorder: A systematic literature review. Developmental Review, 60, 100960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2021.100960

- Dotterer, A. M., McHale, S. M., & Crouter, A. C. (2007). Implications of out-of-school activities for school engagement in African American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36(4), 391–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9161-3

- Downey, D. B., & Condron, D. J. (2016). Fifty years since the Coleman Report: Rethinking the relationship between schools and inequality. Sociology of Education, 89(3), 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040716651676

- Drane, C. F., & Barber, B. L. (2016). Who gets more out of sport? The role of value and perceived ability in flow and identity-related experiences in adolescent sport. Applied Developmental Science, 20(4), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2015.1114889

- Dworkin, J. B., Larson, R., & Hansen, D. (2003). Adolescents’ accounts of growth experiences in youth activities. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 32(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021076222321

- Eccles, J. S., & Barber, B. L. (1999). Student council, volunteering, basketball, or marching band: What kind of extracurricular involvement matters? Journal of Adolescent Research, 14(1), 10–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558499141003

- Eccles, S. E., Barber, B. L., Stone, M., & Hunt, J. (2003). Extracurricular activities and adolescent development. Journal of Social Issues, 59(4), 865–889. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0022-4537.2003.00095.x

- Enders, C. K., & Bandalos, D. L. (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 8(3), 430–457. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_5

- Farb, A. F., & Matjasko, J. (2012). Recent advances in research on school-based extracurricular activities and adolescent development. Developmental Review, 32(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2011.10.001

- Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2005). Developmental benefits of extracurricular involvement: Do peer characteristics mediate the link between activities and youth outcomes? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(6), 507–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-005-8933-5

- Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2008). Participation in extracurricular activities in the middle school years: Are there developmental benefits for African American and European American youth? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(9), 1029–1043. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9309-4

- Fredricks, J. A., & Simpkins, S. D. (2013). Organized out-of-school activities and peer relationships: Theoretical perspectives and previous research. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2013(140), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20034

- Fredricks, J. A., Alfeld-Liro, C. J., Hruda, L. Z., Eccles, J. S., Patrick, H., & Ryan, A. M. (2002). A qualitative exploration of adolescents’ commitment to athletics and the arts. Journal of Adolescent Research, 17(1), 68–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558402171004

- Goodenow, C. (1993). The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools, 30(1), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(199301)30:1 < 79::AID-PITS2310300113>3.0.CO;2-X

- Goodenow, C., & Grady, K. E. (1993). The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. The Journal of Experimental Education, 62(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.1993.9943831

- Gray, M., & Smart, D. (2008). Growing up in Australia: The longitudinal study of Australian children is now walking and talking. Family Matters, 79, 5–13. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/INFORMIT.275761695644391

- Hamaker, E. L., Kuiper, R. M., & Grasman, R. P. (2015). A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychological Methods, 20(1), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038889

- Hamm, J. V., & Faircloth, B. S. (2005). The role of friendship in adolescents’ sense of school belonging. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2005(107), 61–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.121

- Hansen, D. M., Larson, R. W., & Dworkin, J. B. (2003). What adolescents learn in organized youth activities: A survey of self‐reported developmental experiences. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 13(1), 25–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/1532-7795.1301006

- Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683

- Hayes, T., & Enders, C. K. (2023). Maximum likelihood and multiple imputation missing data handling: How they work, and how to make them work in practice. In H. Cooper, M. N. Coutanche, L. M. McMullen, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology: Data analysis and research publication (pp. 27–51). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000320-002

- Heath, R. D., Anderson, C., Turner, A. C., & Payne, C. M. (2022). Extracurricular activities and disadvantaged youth: A complicated—but promising—story. Urban Education, 57(8), 1415–1449. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085918805797

- Jose, P. E. (2013). Doing statistical mediation & moderation. The Guilford Press.

- Jose, P. E., Ryan, N., & Pryor, J. (2012). Does social connectedness promote a greater sense of well-being in adolescence over time? Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22(2), 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00783

- Kidger, J., Araya, R., Donovan, J., & Gunnell, D. (2012). The effect of the school environment on the emotional health of adolescents: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 129(5), 925–949. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2248

- Lareau, A. (2003). Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life. University of California Press.

- Larson, R. W. (2000). Toward a psychology of positive youth development. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 170–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.170

- Lerner, R. M., & Bornstein, M. H. (2021). Contributions of the specificity principle to theory, research, and application in the study of human development: A view of the issues. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 75, 101294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2021.101294

- Leventhal, T., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2000). The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 309–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309

- Leventhal, T., & Dupéré, V. (2019). Neighborhood effects on children’s development in experimental and nonexperimental research. Annual Review of Developmental Psychology, 1(1), 149–176. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-devpsych-121318-085221

- Li, L., Chen, X., & Li, H. (2020). Bullying victimization, school belonging, academic engagement and achievement in adolescents in rural China: A serial mediation model. Children and Youth Services Review, 113, 104946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104946

- Little, R. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722

- Lleras, C. (2008). Do skills and behaviors in high school matter? The contribution of noncognitive factors in explaining differences in educational attainment and earnings. Social Science Research, 37(3), 888–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2008.03.004

- Loft, L., & Waldfogel, J. (2021). Socioeconomic status gradients in young children’s well‐being at school. Child Development, 92(1), e91–e105. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13453

- Loukas, A., Ripperger-Suhler, K. G., & Horton, K. D. (2009). Examining temporal associations between school connectedness and early adolescent adjustment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(6), 804–812. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9312

- Mahoney, J. L., Larson, R. W., Eccles, J. S., & Lord, H. (2005). Organized activities as developmental contexts for children and adolescents. In J. L. Mahoney, R. W. Larson, & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Organized activities as contexts of development: Extracurricular activities, after-school, and community programs. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Martinez, A., Coker, C., McMahon, S. D., Cohen, J., & Thapa, A. (2016). Involvement in extracurricular activities: Identifying differences in perceptions of school climate. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 33(1), 70–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/edp.2016.7

- Masarik, A. S., & Conger, R. D. (2017). Stress and child development: A review of the family stress model. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.008

- McLaughlin, M. W., Irby, M. A., & Langman, J. (1994). Urban Sanctuaries: Neighborhood organizations in the lives and futures of inner-city youth. Jossey-Bass Inc.

- McNeely, C. A., Nonnemaker, J. M., & Blum, R. W. (2002). Promoting school connectedness: Evidence from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. The Journal of School Health, 72(4), 138–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb06533.x

- Meier, A., Hartmann, B. S., & Larson, R. (2018). A quarter century of participation in school-based extracurricular activities: Inequalities by race, class, gender and age? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(6), 1299–1316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0838-1

- Minh, A., Bültmann, U., Reijneveld, S. A., van Zon, S. K., & McLeod, C. B. (2021). Childhood socioeconomic status and depressive symptom trajectories in the transition to adulthood in the United States and Canada. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 68(1), 161–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.033

- Modecki, K. L., Blomfield Neira, C., & Barber, B. L. (2018). Finding what fits: Breadth of participation at the transition to high school mitigates declines in self-concept. Developmental Psychology, 54(10), 1954–1970. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000570

- Morris, D. S. (2015). Actively closing the gap? Social class, organized activities, and academic achievement in high school. Youth & Society, 47(2), 267–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X12461159

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide. 8th ed. Muthén & Muthén.

- Neely, S. R., & Vaquera, E. (2017). Making it count: Breadth and intensity of extracurricular engagement and high school dropout. Sociological Perspectives, 60(6), 1039–1062. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731121417700114

- O’Donnell, A. W., & Barber, B. L. (2018). Exploring the association between adolescent sports participation and externalising behaviours: The moderating role of prosocial and risky peers. Australian Journal of Psychology, 70(4), 361–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12203

- O’Donnell, A. W., & Barber, B. L. (2021). Ongoing engagement in organised activities may buffer disadvantaged youth against increasing externalising behaviors. Journal of Leisure Research, 52(1), 22–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2020.1741328

- O’Donnell, A. W., Redmond, G., Skattebol, J., Allen, J., Thomson, C., & MacDougall, C. (2023). The relationship between financial hardships and the development of risk-taking behaviors: The protective role of extracurricular activities. Youth & Society, 55(5), 895–923. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X221127724

- O’Donnell, A. W., Redmond, G., Thomson, C., Wang, J. J., & Turkmani, S. (2022). Reducing educational disparities between Australian adolescents in regional and metropolitan communities: The compensatory effects of extracurricular activities. Developmental Psychology, 58(12), 2358–2371. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001434

- O’Donnell, A. W., Stuart, J., Barber, B. L., & Abkhezr, P. (2020). Sport participation may protect refugee youths resettled in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities from experiencing behavioral and emotional difficulties. Journal of Adolescence, 85(1), 148–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.11.003

- Oberle, E., Ji, X. R., Guhn, M., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., & Gadermann, A. M. (2019). Benefits of extracurricular participation in early adolescence: Associations with peer belonging and mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(11), 2255–2270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01110-2

- Ou, L., Chen, J., & Hillman, K. (2017). Socio-demographic disparities in the utilisation of general practice services for Australian children-Results from a nationally representative longitudinal study. PloS One, 12(4), e0176563. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176563

- Rapee, R. M., Oar, E. L., Johnco, C. J., Forbes, M. K., Fardouly, J., Magson, N. R., & Richardson, C. E. (2019). Adolescent development and risk for the onset of social-emotional disorders: A review and conceptual model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 123, 103501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.103501

- Rees, C. R., Howell, F. M., & Miracle, A. W. (1990). Do high school sports build character? A quasi-experiment on a national sample. The Social Science Journal, 27(3), 303–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/0362-3319(90)90027-H

- Ren, L., Chen, J., Li, X., Wu, H., Fan, J., & Li, L. (2021). Extracurricular activities and Chinese children’s school readiness: Who benefits more? Child Development, 92(3), 1028–1047. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13456

- Rose-Krasnor, L., Busseri, M. A., Willoughby, T., & Chalmers, H. (2006). Breadth and intensity of youth activity involvement as contexts for positive development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(3), 365–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9037-6

- Roth, J. L., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2016). Evaluating youth development programs: Progress and promise. Applied Developmental Science, 20(3), 188–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2015.1113879

- Sanson, A., Nicholson, J., Ungerer, J., Zubrick, S., Wilson, K., Ainley, J., Berthelsen, D., Bittman, M., Broom, D., Harrison, L., Rodgers, B., Sawyer, M., Silburn, S., Strazdins, L., Vimpani, G., & Wake, M. (2002). Introducing the longitudinal study of Australian Children: LSAC Discussion Paper N0.1. https://growingupinaustralia.gov.au/data-and-documentation/discussion-papers

- Schaefer, D. R., Simpkins, S. D., Vest, A. E., & Price, C. D. (2011). The contribution of extracurricular activities to adolescent friendships: New insights through social network analysis. Developmental Psychology, 47(4), 1141–1152. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024091

- Selig, J. P., & Preacher, K. J. (2009). Mediation models for longitudinal data in developmental research. Research in Human Development, 6(2–3), 144–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427600902911247

- Shochet, I. M., Dadds, M. R., Ham, D., & Montague, R. (2006). School connectedness is an underemphasized parameter in adolescent mental health: Results of a community prediction study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology: The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 35(2), 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_1

- Shulruf, B. (2010). Do extra-curricular activities in schools improve educational outcomes? A critical review and meta-analysis of the literature. International Review of Education, 56(5–6), 591–612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-010-9180-x

- Simpkins, S. D., Vest, A. E., Delgado, M. Y., & Price, C. D. (2012). Do school friends participate in similar extracurricular activities?: Examining the moderating role of Race/Ethnicity and age. Journal of Leisure Research, 44(3), 332–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2012.11950268

- Sirin, S. R. (2005). Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Review of Educational Research, 75(3), 417–453. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543075003417

- Stearns, E., & Glennie, E. J. (2010). Opportunities to participate: Extracurricular activities’ distribution across and academic correlates in high schools. Social Science Research, 39(2), 296–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.08.001

- Steinberg, D. B., & Simon, V. A. (2019). A comparison of hobbies and organized activities among low income urban adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(5), 1182–1195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01365-0

- Stride, C. B., Gardner, S., Catley, N., & Thomas, F. (2015). Mplus code for mediation, moderation, and moderated mediation models. http://www.offbeat.group.shef.ac.uk/ FIO/mplusmedmod.htm

- Thomson, S., De Bortoli, L., & Underwood, C. (2017). PISA 2015: Reporting Australia’s results. ACER Press.

- Tudge, J. R., Mokrova, I., Hatfield, B. E., & Karnik, R. B. (2009). Uses and misuses of Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory of human development. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 1(4), 198–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2589.2009.00026.x

- Urban, J. B., Lewin-Bizan, S., & Lerner, R. M. (2009). The role of neighborhood ecological assets and activity involvement in youth developmental outcomes: Differential impacts of asset poor and asset rich neighborhoods. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30(5), 601–614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2009.07.003

- Usami, S., Murayama, K., & Hamaker, E. L. (2019). A unified framework of longitudinal models to examine reciprocal relations. Psychological Methods, 24(5), 637–657. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000210

- von Salisch, M., Zeman, J., Luepschen, N., & Kanevski, R. (2013). Prospective relations between adolescents’ social‐emotional competencies and their friendships. Social Development, 23(4), 684–701. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12064

- Waters, S., Cross, D., & Shaw, T. (2010). Does the nature of schools matter? An exploration of selected school ecology factors on adolescent perceptions of school connectedness. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(Pt 3), 381–402. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709909X484479

- Wiersma, L. D. (2000). Risks and benefits of youth sport specialization: Perspectives and recommendations. Pediatric Exercise Science, 12(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1123/pes.12.1.13

- You, S., Ritchey, K. M., Furlong, M. J., Shochet, I., & Boman, P. (2011). Examination of the latent structure of the psychological sense of school membership scale. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 29(3), 225–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282910379968