ABSTRACT

Animal welfare concerns have plagued the professional zoo and aquarium field for decades. Societal differences remain concerning the well-being of animals, but it appears a shift is emerging. Scientific studies of animal welfare have dramatically increased, establishing that many previous concerns were not misguided public empathy or anthropomorphism. As a result, both zoo and aquarium animal welfare policy and science are now at the center of attention within the world’s professional zoos and aquariums. It is now possible to view a future that embraces the well-being of individual captive exotic animals, as well as that of their species, and one in which professional zoos and aquariums are dedicated equally to advancing both. Though the ethics of keeping exotic animals and animals from the wild in captivity are still a contentious subject both outside and even within the profession, this study argues. We argue that this path forward will substantially improve most zoo and aquarium animals' welfare and could significantly reduce societal concerns. If animal welfare science and policy are strongly rooted in compassion and embedded in robust accreditation systems, the basic zoo/aquarium paradigm will move toward a more thoughtful approach to the interface between visitors and animals. It starts with a fundamental commitment to the welfare of individual animals.

The Detroit Zoological Society (DZS) has long challenged zoos’ and aquariums’ relative reluctance to acknowledge gaps in the welfare of exotic nonhuman animals in captivity and has facilitated efforts to recalibrate zoo and aquarium practices and policies accordingly. This challenge has been directed both at the level of base assumptions and through evidence-based research. It has partly developed in the context of external and internal pressures from public and staff as well as distinct but overlapping animal communities including sanctuaries, conservation organizations, animal welfare organizations, animal protection organizations, and animal rights organizations. Zoos and aquariums identify themselves as conservation organizations, but in the future, they must adopt and embrace identification as animal welfare organizations as well with a clear focus on individual animal well being. This evolution will place the emphasis on the experiences of the animals as they are provided with lifelong sanctuary in places safe for humans and nonhumans alike. Although shifts in philosophy and practice may appear aspirational in some cases, a sanctuary-like model is attainable and will enable zoos and aquariums to fully execute their missions, while aligning with evolving societal expectations.

The foundation of a sanctuary-based model rests not on exhibition or breeding (for all intents and purposes, both are prohibited), but on the welfare of individual animals (Kagan, Citation2017). This foundation provides zoos and aquariums with moral grounding and a license to engage in their traditional mission elements like education and conservation. Understanding and addressing how each individual animal perceives their well being is the starting point. From this point, we can also help millions of people who visit zoos and aquariums understand and respect animals in captivity as individuals who experience the world in species-specific and individually unique ways.

Obviously, those who work in the world’s accredited zoos and aquariums are dedicated to being experts in exotic animal care and conservation. We all are deeply concerned about wild places and what is best for both animals in the wild and captive animals. Even today, though, not every zoo and aquarium professional fully understands a critical component of captive animals’ worlds: the difference between good care and good welfare.

Caring is provisioning, or providing for basic needs to sustain life. Provisioning well is part of a foundation for good welfare, but by itself, it does not ensure that an individual will experience great welfare. Great welfare is possible when physical, social, and psychological needs are met, including the critical need all animals have for agency to make decisions and exercise choice and control in their daily lives (Kagan & Veasey, Citation2010). Though often seen as a provocative analogy, it is easy to “keep” humans in prison healthy for a long lifetime (and they can even reproduce if given the opportunity). But few would argue that they experience great welfare, despite receiving the provisions/care that they need to survive.

By making clear the distinction between good care and good welfare, we attempt to enhance, expand, and legitimize to some extent the zoo and aquarium communities’ standing as providers of excellent social, psychological, and physical environments for captive animals. In particular, the burgeoning field of animal welfare science has enabled the profession to effectively tackle a number of welfare concerns if it so chooses. This growing knowledge also, however, acknowledges and challenges existing limitations in zoos and aquariums with respect to both individual animal welfare and species welfare (conservation).

Zoo and aquarium professionals have multiple responsibilities to animals. In areas of basic management, breeding, nutrition, and veterinary care, we have seen significant improvements and advancements for decades, but welfare questions remain. More than 20 years ago, Malamud (Citation1998) wrote that the zoo community claimed to have made major improvements for decades and also claimed there were continuing dramatic advancements, yet the welfare of animals in zoos had not significantly advanced. Now 20-plus years later, one might reasonably resurrect Malamud’s pointed question and reach a similar conclusion. Animal welfare in zoos and aquariums has seen much more attention in discussion and in research, but meaningful advances have not been obvious or abundant, including to many who continue to question the relevance of zoos and aquariums.

We are not currently able to declare that welfare conditions in U.S.-accredited zoos and aquariums are so well developed that essentially all captive animals are thriving. We need to be fully open to objective, professional, external, and independent reviews that challenge our own assessment. If we are not open to these reviews and we keep telling ourselves that we have already accomplished a state of “thriving,” we are doing a disservice to ourselves and the animals to whom we are so committed. Great intentions and action are essential to make the kind of comprehensive progress that is long overdue.

Many professions have inconsistencies between aspirations and activities, operations, and achievements. Many acknowledge they are on a journey to fully align all activities and policies with missions, and this is certainly true for zoos and aquariums. Zoos and aquariums accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) define themselves as conservation organizations, yet more than half are not meeting AZA-suggested recommendations for even a minimal level of field conservation investment. The vast majority are not carbon-neutral in their operations, most serve foods that are not from environmentally sustainable sources, and most still sell plastic water bottles, which contribute to significant plastic pollution. These operational practices are not consistent with being environmentally responsible, but we know and seemingly accept that economics and other factors dissuade progress.

The same is true for animal welfare. More and more zoos and aquariums identify animal welfare as a priority, but few if any identify themselves as animal welfare organizations. There has been more discussion of welfare at professional meetings, including discourse hosted by the Chicago Zoological Society and the DZS and its Center for Zoo and Aquarium Animal Welfare and Ethics. But many do not currently see most zoos and aquariums as urgently working to align actions and change with the values we stated concerning animal welfare.

In addition to the reality that accredited zoos and aquariums are not consistently performing in ways that align with stated goals or aspirations for both conservation and animal welfare, there is also perceived conflict between those two goals with prioritization of conservation over animal welfare often being evident. This prioritization often comes down to resources. For example, caring for individuals not needed for the sustainability of a wild or captive population reduces the resources available toward conservation breeding. However, providing lifelong care for animals, regardless of their “value” in terms of a population or genetics is a clear mandate of animal welfare. Underrating welfare is ethically questionable. It is crucial for us to realize that although we continue to do greater and greater work in species conservation, it cannot be done at the expense of individual animal welfare. It is also clearly not a legitimate justification to ignore or fail to invest in welfare work. Conservation and welfare are not always or completely mutually exclusive in zoos and aquariums, but they do require different priorities, tasks, and goals. Both are necessary today and in the future for zoos and aquariums.

One zoo’s ongoing journey

For more than 25 years, DZS has been working with an obscure, small invertebrate, the Partula snail. This “uncharismatic” animal is not an obvious crowd-pleaser, and conserving this animal is in contrast to a great deal of zoo and aquarium conservation work that has been focused on “appealing” mega-vertebrates. This speciesism can be counterproductive to a broader goal of helping nature. Rethinking decisions about the animals with whom we work (especially given limited resources and massive environmental needs/threats) will help us ensure that zoos and aquariums are not running conservation programs like beauty contests.

As an example, the conservation community has known for two decades that amphibians in nature are in a crisis. Eighteen years ago, the National Amphibian Conservation Center (the Wall Street Journal called it “Disneyland for Toads”, Gubernick, Citation2000) opened at the Detroit Zoo. It is a center for amphibian care, conservation breeding, research, and display, and it is still the only facility of its size in the world. It is also popular and therefore compelling evidence that organizations do not have to work with charismatic mega-vertebrates to be effective at conservation or to be valued by visitors. Other accredited zoos and aquariums work to save species about which the general public knows little; they just do not work to save enough of them. Cincinnati Zoo’s World of the Insect and Audubon Nature Institute’s Insectarium are examples of impactful exhibition and public education that reflect a deeper commitment to a wider conservation approach. We need to applaud and expand that approach and investment because it currently represents a small fraction of current emphasis.

Like others in the zoo and aquarium community, DZS is engaged in field conservation work all over the world. Often, the work is in collaboration with partners like the Humane Society International, Jane Goodall Institute, and others. Leveraging our considerable knowledge of animals as well as our resources with those entities who work on a regular basis in the wild can lead to greater impact with programs, especially those involving education, reintroduction, and human–wildlife conflict management. If we are to be successful at creating a viable future for animals and a path to a better relationship between humans and nonhumans, we need to expand these partnerships, especially with animal protection and welfare organizations.

We must also use our resources not only to conduct important conservation work, but to educate the public as well about both welfare and conservation. In 2015, DZS created a multiacre gray wolf habitat in part so that governmental policies regarding wolf hunting in Michigan would have a public platform and face. It was important for DZS to establish legal standing and to be able to communicate with 1.5 million annual visitors. Most Americans do not know that during the past 100 years, only 2 people have been killed by wild wolves. Most also do not understand the importance of apex predators in healthy ecosystems, so it became an opportunity to advance a more complete understanding of the value of intact ecosystems. We advocate for a humane relationship between humans and nonhumans, including both indigenous and nonindigenous (often unfortunately referred to as “invasive”) wild animals.

Living our mission

Conservation goes beyond research and protection of threatened species in nature. The electric energy at DZS facilities is completely powered by renewable sources. As conservation organizations, we should reflect resource conservation in everything we do. The DZS does not sell bottled water to visitors, and the boardwalk over a native wetlands habitat is made out of recycled plastic bottles. The DZS recently commissioned the first and only zoo anaerobic digester in the country. Manure from hundreds of animals and food waste from 1.5 million guests each year are diverted from traditional waste streams and instead help power the zoo’s animal health complex. Zoos and aquariums must execute their conservation mandates, including by reducing their resource use footprints and impacts.

As conservationists who attract millions of people each year to our institutions, it is our responsibility to engage people in ways that are effective and impactful. Projection technology, like Science on a Sphere, dramatically expands our ability to engage visitors by showing them global events and phenomena, such as environmental impacts resulting from climate change. In the course of one minute, Science on a Sphere allows people to see Earth from 2000 miles in space and clearly shows what has happened during the past 100 years with respect to shrinking polar ice caps. There is little denial about climate change when it is experienced this way.

In the DZS Ford Education Center, an academy for humane education and a humane science lab were created to help teachers and students learn about biology and science without harming animals. Models and simulations are used (rather than once-living animals) for dissection and study. The Ford Education Center also houses the Wild Adventure Simulator, which utilizes theater and technology to get people to think, experience, and feel what another being might experience. This motion-based cabin enables people to “become” different animals. It creates a degree of understanding and empathy that we hope stimulates reflection about what nonhuman animals are experiencing in increasingly human-impacted environments.

Future zoos and aquariums will certainly embrace exciting technological promises. Four-dimensional (4D) theaters, simulators, Science on a Sphere, and virtual and augmented reality experiences all offer opportunities for people to experience nature and wildlife in ways they simply cannot in the wild. Although these experiences may not be “real,” they are proving to be popular and educational with guests, and most importantly, they do not harm animals or compromise ethics.

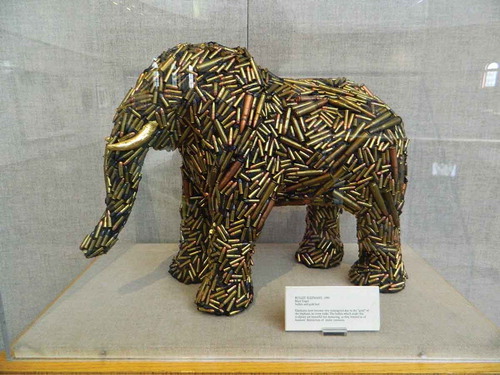

Similarly, art and theater can help us engage our visitors and compel them to think about their actions and impacts on animals and the environment. The commissioned “bullet elephant” on exhibit at the Detroit Zoo () provokes people to think about our relationship with some animals in ways they previously had not. It is also a poignant reminder that if AZA organizations are directly engaged in major elephant conservation work, including public awareness campaigns like 96 Elephants, there is no excuse for compromised elephant welfare in accredited zoos. The DZS also produced a film entitled From Animal Showboat to Animal Lifeboat about the evolution of zoos and aquariums from places of entertainment to centers for conservation and sanctuary.

Figure 1. Bullet elephant sculpture commissioned by the Detroit Zoological Society (DZS). Photo courtesy of the DZS.

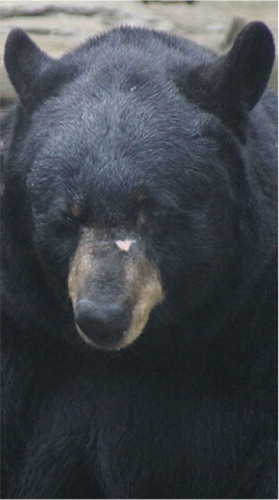

Living our mission also impacts how animals come to live at zoos and aquariums. SeaWorld parks have rescued more than 20,000 animals. Many are ultimately released back into the wild. The DZS has been rescuing animals for more than two decades, including a lion found chained as a guard animal in the basement of a Detroit crack house, a polar bear from a Mexican circus, and nearly 1000 amphibians and reptiles confiscated from a Texas warehouse. The DZS has also rescued lions from a junkyard in Kansas, as well as a wallaby who had been confined to a cage in a residential garage and can now be found living in the Australian Outback habitat at the Detroit Zoo. Hamms, a black bear (), was reportedly a beer company mascot who was sold off after he became too big to safely handle. He was beaten and even pitchforked by neighbors of his Iowa farm caregiver (owner) before being confiscated and sent to the Detroit Zoo, where he lived for many years. The DZS has rescued race horses so that we can inform our community about the lack of proper retirement planning within the horse racing industry and thereby motivate the public to weigh in on this issue.

Figure 2. Hamms the black bear who found sanctuary at the Detroit Zoo. Photo courtesy of the Detroit Zoological Society.

Animals in the wild also find themselves in need of sanctuary at times. Grizzly bear cubs came to the DZS when their mother was shot in early winter in Alaska. And so, too, did several injured, nonreleasable seals from the wild. Like many accredited zoos and aquariums, we help lead rescue work in the wild following human-caused disasters like oil spills. Although the animals saved in these efforts do not live on our campus, the importance of this type of rescue work cannot be overstated.

Sometimes “rescue” means bringing animals into our facilities, and sometimes it means sending them to other facilities. In 2005, the Detroit Zoo ended its elephant program, and though far from an intentional outcome, it created a controversy within our profession. Our community did not find the decision controversial, and in fact, the Detroit Zoo’s audience has grown significantly since that decision. Our decision followed years of improvements to physical environments (especially expanding space) and critical introspection about how the elephants lived in a small (for an elephant) area of one acre in a region characterized by cold winters with ice and snow. This introspection also included considering the impacts of being kept in a clearly unnatural, extremely limited social environment. Future zoos and aquariums must continue to be self-critical about all their practices and must continuously test their assumptions about how animals are faring against information learned from robust programs of animal welfare research and known natural history.

Self-critical thinking should extend to all captive animals, and we are currently considering more changes for similar ethical reasons. Perhaps it is obvious that in zoos, many birds cannot fly (or barely can) because of the size limitations of aviaries or because maintaining them flightless is an easier way to keep them in many of our enclosures. A huge aviary (by current standards) has to be constructed to allow large birds to fly properly. This challenge is especially daunting for any zoo in a snowy region because of the engineering and construction needed to handle snow loads. This should be an important consideration because normal/natural locomotion obviously needs to be possible for any captive animal. The DZS has started moving some individual birds out, including some vultures and some other large birds, to places that do have large aviaries and are in climates that do not have to worry about snow loads. As of today, few fully adequate aviaries may exist in AZA facilities.

Rescue work comes in many forms and allows us to extend our efforts beyond exotic animals. In 1993, the DZS partnered with dozens of Michigan-based humane organizations in what would become the largest ongoing remote domestic companion-animal (pet) adoption in the country. Meet Your Best Friend at the Zoo has placed more than 25,000 rescued dogs and cats in homes and continues to be a popular community event each spring and fall.

The DZS’s commitment to animal welfare is evident in other targeted initiatives. In 2001, the DZS hosted an AZA regional conference themed “Animal Welfare 911.” 9-1-1 is the emergency call number in the United States, and even at that time, several professionals in the zoo and aquarium community felt that an animal welfare emergency existed within AZA (never mind nonaccredited facilities). It was of great concern that we were not acknowledging the perceived gap and therefore were not addressing it. Many in the accredited zoo and aquarium community would argue that there still is a long way to go.

The DZS Center for Zoo Animal Welfare was created in 2008. The center was established to host symposia/conferences and training workshops, to acknowledge advances through welfare awards, to conduct animal welfare research, and to establish a major animal welfare resource center freely accessible to all. That resource center has grown to nearly 8000 references. The center’s workshops, “From Good Care to Great Welfare,” provide staff from zoos and aquariums from around the world with unique training and experience in applied exotic animal welfare. In part through activities that place staff “behind the eyes” of animals in habitats, participants are more able to recognize the senses and experiences that captive animals may be experiencing. This experience can build empathy and a keener appreciation for challenges animals face in zoo and aquarium life. Research on welfare undertaken by staff at the center has included the use of infrared thermography as a noninvasive welfare assessment tool that can monitor stress responses and help to understand visitor impacts on animals.

For this American community and its zoological society, it has been a decades-long journey with both gradual changes and some major milestones. It has proven to be a good business decision (continuously expanding audience/visitation) to do what is best for individual animals, not just for species.

The journey before us

As we consider the future for zoos and aquariums, we should be fully cognizant of the past. Many of the world’s best zoos and aquariums were very much (perhaps solely) focused on displaying nature’s oddities. They were menageries, collections of nonhuman animals (with notable exceptions like the Congolese man Ota Benga in the early 20th century). Today, it can be shocking to read about what was done a century ago, such as exhibiting people from other lands in zoos and catching gorillas from the wild for display knowing they would quickly die:

The only specimen which up to 1901 had reached America alive, lived but five days after its arrival. Despite the fact that these creatures seldom live in captivity longer than a few months, they are always being sought by zoological gardens. The agents of the New York Zoological Society are constantly on the watch for an opportunity to procure and send hither a good specimen of this wonderful creature: and whenever one arrives, all persons interested are advised to see it immediately—before it dies of sullenness, lack of exercise, and indigestion. (Hornaday, p. 83, Citation1913)

Not long ago, some accredited zoos kept polar bears in tropical and desert climates, while chimp shows continued in others. As with many other societal norms, these practices have thankfully changed. Indeed, a lot has changed in modern accredited zoos and aquariums in the West. But we cannot escape the profession’s history and the fact that some practices that we shun now remain prevalent in other zoos and aquariums that label themselves the same way we do. They outnumber us at least 10 to 1 but do not share our values, standards, or practices. Is it not our unique ability and professional responsibility to engage in public awareness efforts and advocacy related to all captive exotic animal conditions? Should we not challenge their practices?

We know we are not the same as we were, but we have to realize that society wonders about our stated commitment to animals, including conservation, if their perceived notions of our actions appear to lack full concern for individual animals. The ethics of orca captivity and shows and the legitimacy of captivity for elephants and dolphins (and other species) continue to emerge as hotly debated issues in many US communities because of perceived (and likely real) compromised animal welfare. Communities need to hear from us (and see in our policies and practices) how focused and obsessed we are about improving conditions. Ringling Brothers recently stopped elephant performances, but there still is a connection between the accredited zoo world and the circus world surrounding elephants. It seems ethically inconsistent with our values if our profession has a real commitment to elephant welfare.

Zoos and aquariums are one societal reflection of how humans think and feel about other animals. When one species creates a place and captures and/or confines other species for public or private human enjoyment, a display paradigm has been established. As Gruen (Citation2014) stated, “[A]nimals should be provided with places to hide that are recognizable to them as hiding places given their species-specific behaviors. In captivity, we can respect the wild dignity of animals by allowing them to be seen only when they want to be seen …” (p. 245). A better future reflecting evolving societal values and a strong ethical foundation would look and operate like a sanctuary, with different expectations of visitors and with no or extremely limited breeding and only then for essential conservation efforts.

An important book was published in Citation1992, How Monkeys See the World (Cheney & Seyforth). Our question should be, “How do zoo monkeys see their world?” One sees reptile and monkey indoor habitats that have artistic murals. Is that for us or the animals? It seems silly to think that a snake sees it and thinks, “I’m in Thailand.” So, is this an illusion for visitors that masks the enormous limitations of the artificial physical environment from visitors, staff, and animals? We have to be careful not to convince ourselves that doing some of the artificial exhibition decorating is great (or even good) or that somehow we have created something natural.

Although almost inconceivable a few decades ago, it may be that there are situations in which life is better for some individual animals in zoos and aquariums than it is in the wild. This is not to suggest that we should take animals out of the wild, and it is now rarely done within the accredited zoological community. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to observe that the life of a penguin in Antarctica is difficult at best. The birds are constantly assaulted by predators both in the sea and on land, and they are regularly challenged to find food. They are often forced to move due to the rapid degradation of areas affected by human-induced climate change. Would a penguin from the wild choose to live at a place like the DZS Polk Penguin Conservation Center? This is not to argue that “agency” is not a fundamental, indeed crucial dimension to address nor that a degradation of life in the wild for many species and individuals is a justification for bringing animals into captivity. It is, however, an argument for the type of thought that must go into the design of habitats for animals living in the care of humans.

For 20 years, a simple model and exercise was used to help compare a captive animal’s quality of life to that of its counterpart in the wild (see the Appendix). In AZA’s management school and Michigan State University’s applied zoology program, students wrestled with how individuals of different species might fare in a comparative sense. Though not designed as a scientific assessment, it did help hundreds of current and future professionals consider those physical and social elements that affect one’s sense of well being.

We know that many environmental factors have the potential to affect the well being of captive animals. However, there still remain large gaps in the related research being conducted and thus in our knowledge to understand and either avoid or compensate for these impacts. An animal’s physical environment needs to be appropriate, meaning not beyond an animal’s ability to cope with the correlated and somewhat unavoidable stressors. The climate and weather variations need to be within a range in which an animal can not only cope, but thrive. This climate is under our control because we choose which species to hold in each facility and location. However, the impact of local climate and weather has been severely understudied (e.g., in penguins, Ozella, Anfossi, Di Nardo, & Pessani, Citation2015; in lions and tigers, Young, Finegan, & Brown, Citation2013), but it is not difficult to imagine its appropriateness if a species’ natural history is properly considered.

Other factors are also under our control, as we can affect the olfactory, visual, auditory, tactile, and thermal environments (Morgan & Tromborg, Citation2007). These abiotic factors are important but clearly are not always considered by zoological facilities, even though we should know that they contribute to an animal’s perception of their own quality of life.

Similarly, the effect of visitors has been examined in only a few species (e.g., penguins, Sherwen, Magrath, Butler, & Hemsworth, Citation2015; chimpanzees and lemurs, Hosey et al., Citation2016). Though some attention has been given to certain aspects, such as the impact of anthropogenic noise (e.g., Orban, Soltis, Perkins, & Mellen, Citation2017), little is known about others (e.g., the loud noises in holding buildings made by staff and hard, metallic surfaces), including the role of olfaction in welfare (Campbell-Palmer & Rosell, Citation2017). How is welfare impacted by noxious smells created by cleaning agents or stressful smells created by nearby prey or predators from which an animal cannot “escape”? We have a critical responsibility to recognize our contributions, or indeed intrusions, to the experience of captive animals.

In the future, could zoos be redesigned to ensure that captive animals have a full natural environment and thereby allow for all the same experiences both animals and visitors have on a photographic safari? Safaris are incredible wildlife experiences, and humans are not (in principle) interfering or compromising the animals whom they encounter. Having people pay to have such great experiences in a future zoo or aquarium would genuinely benefit conservation without compromising animal welfare (in contrast to the current paradigm of conservation contributions by individuals or organizations that pay to hunt as a “conservation” activity). The type of wildlife safari in a zoo (or underwater in a different kind of aquarium) of the future requires either a virtual experience or an exponentially larger type of zoo or aquarium physically. It will entail an exponentially larger investment and reframing of public expectations, including having patience because seeing animals may take more effort. However, it would almost certainly be a better experience for humans. And importantly, it would ensure a much better life for the captive nonhumans. A few examples of accredited, safari-like zoos already exist and are sustainable business models. No aquariums have yet to develop this model.

Accreditations and welfare

All zoos and aquariums are not created equal, and one important distinction is accreditation by the AZA. The AZA’s rigorous, scientifically based, and publicly available standards examine a zoo or aquarium’s entire operation, including animal welfare, veterinary care, conservation, education, guest services, physical facilities, public safety, staffing, finance, and governance. The AZA standards are performance-based so they can be applied in a variety of different situations and cases. The AZA continuously raises its standards as science continues to learn more and more about the species in our care. Accreditation is rescinded if AZA standards are not maintained. In the United States, agencies such as Occupational Safety and Health Administration and the United States Department of Agriculture consider AZA standards and accreditation as the “national” standard, and they refer to those standards when evaluating all institutions.

The DZS developed a universal welfare framework for zoos and aquariums () that could (and should) be woven into accreditation processes (Kagan, Carter, & Allard, Citation2015). Zoos and aquariums should have welfare frameworks that are carefully crafted and utilized by all. These frameworks should start with institutional philosophy and policy, followed by allocation of the full resources to execute the effort. Finally, these frameworks need to be continuously evaluated and refined. The goal must be that every captive animal is thriving and is in a zoo or an aquarium for a very clear and easily defensible reason, not simply for display. A robust welfare framework should be central to all accreditation processes, as it is in Australia.

Figure 3. Primary elements of a universal captive animal welfare framework, adapted from Kagan et al., Citation2015.

Zoos and aquariums may very well have a troubled future unless we address current and predictable questions as societal values change and knowledge grows. We have to dramatically advance animal well being, which needs to be validated by external animal well being experts. It should be a requirement for accreditation. We will have to be “tuned in” to the animals by being “patient-centered” as human health care institutions are more and more becoming. This may be an unlikely comparison for some professionals because the animals are not ill, but the focus should be on what they need and want, not what is easiest for professionals to manage or visitors to see.

Helping species and populations is critical, and zoos and aquariums contribute to helping species and populations in terms of conservation. However, as we have stressed here, we must be committed to ensuring that captive individuals thrive. Animals have to be able to react naturally to whatever confronts them in their various physical and social environments. And they have to be able to initiate natural behaviors, not just react. Crucially, we must create optimal, not minimal, physical and social environments. Our current standards still start from minimum baselines with no clear guidance about, or mandate for, optimal standards.

Future zoos and aquariums will make sure that all animal environments (physical, psychological, and social) are outstanding for the animals first and foremost. We will need to help the public recalibrate their expectations of seeing animals and help them recognize that animals are not always active (none are) and are not always viewable immediately and without effort. These new facilities and policies will all feature a lot of control and choice for each individual animal, with recognition that each one (just like humans) is different and each has a “personality” with all that accompanies that construct. Zoos and aquariums now and in the future must return agency to captive animals. Many of the decisions we make for the animals in our care (although well intentioned) could be given back to them, so that choice, control, and preference are theirs to the fullest extent possible.

The future will surely involve only keeping and caring for appropriate species. That “appropriateness” will involve consideration of climate and its relationship to species and individuals for a particular zoo or aquarium (especially in the case of medium-to-large animals). It remains a surprisingly minor or absent consideration in many cases. Even without the clarity of hindsight, it was obvious to zoo personnel (even if it might not have been to the public) that polar bears did not belong in tropical or desert climates. That situation was under the watch of our previous generation of professionals, but we need to really think about how bad it was and be far more thoughtful and active about not repeating this type of mistake with any animal. Of course, many other criteria are essential, so the living population of nonhumans should be tailored in each facility based on dozens of criteria and not just genetic considerations, compatibility, or popularity. Ultimately, the future is likely to be one in which we find far fewer animals and far fewer species in each accredited zoo and aquarium with an absolute, equal, and foundational focus on the quality of life for all animals.

We have to confront whether it is ever going to be possible to adequately create captive conditions in which cetaceans, elephants, and in some cases, great apes and large carnivores could thrive. We need to dive deeply into the ethics of keeping some birds. Will we continue to prevent and/or restrict essentially all captive birds (and other flying/gliding vertebrates) from even the most basic flight? A small aviary significantly, if not almost entirely, limits any flighted bird’s need and desire to locomote. And the assertion that if there’s ample food, water, and shelter, birds do not need or want to fly, cetaceans do not need or want to travel, and elephants do not need or want to roam is baseless and does not align with what we know about natural history. Future zoos and aquariums will resist speciesism and be viewed as guardians, not exhibitors or owners.

Zoos and aquariums of the future must be committed to the care of each animal for life. There should be retirement plans for every animal so there is a cradle-to-grave commitment (Carter & Kagan, Citation2010). Culling healthy animals in zoos and aquariums because they may not be genetically important to captive populations is ethically unsound. There should continue to be discussion about the culling (often erroneously but intentionally referred to as euthanasia) that goes on in zoos and aquariums. Though rarely shared with our communities, it needs to be wrestled with because it may be seen by many as conflicting with our mission to save animals.

Other policies and practices that will be challenged more and more in the future unless they are abandoned or fundamentally changed include discontinuing public nurseries. Quite simply, they are stressful, and unless they are designed to prevent negative welfare impacts and are done for truly humanitarian reasons, they are ethically wrong. Additionally, there should be very little breeding other than for species and individuals who need to be bred for conservation purposes, not simply exhibition. Like nurseries, exotic animal outreach programs, often called ambassador programs, can be stressful and are misguided as they encourage and not discourage both the desire of some to own exotics and the idea that it is fine for the animals to be manipulated (and thereby stressed) even though they are not domesticated. This ethically questionable practice often psychologically alters animals.

Similarly, we need to disconnect from commerce that is exploiting individuals as living trophies. Living beings should not be considered objects that are bought and sold. The fact that some accredited facilities still sell and buy animals is surely anachronistic. Considering endangered beings as property is a mind set ripe to discard now. Though not a new topic, “pest” control in zoos also needs much more thought and compassion. Similarly, the feeding of live animals, including invertebrates, needs to be approached with welfare in mind and not just that of the animals being fed, but of those who become food.

Future zoo and aquarium vocabulary will evolve. Using the word “collection” for living beings underlies a foundation of equating wild animals to objects and property. The same is true for the terms “specimen” and “ambassador.” No exotic animal volunteered to represent or sacrifice himself or herself for their species.

Future zoos and aquariums will challenge our current assumptions, knowing that good intentions do not always lead to good outcomes, especially in the realm of animal welfare. Zoos and aquariums will have to be open and transparent. It will require constant, rigorous professional and independent evaluation. The profession must be able to raise difficult issues, struggle, and solve them with a base of ethics as well as welfare science. And we will need to talk to the public about numerous complex and controversial issues because major changes may be unknown and unexpected for them. Like many professions, we have not (for the most part) been willing to openly share these challenges especially outside our profession. These conversations include animal welfare issues but also topics like impacts of climate change.

We will need to be outspoken on exotic animal well being and on human responsibility, especially as it relates to captive animals. We need to speak out about bad zoos and aquariums or other compromised conditions/situations that involve wild and exotic animals. We are too quiet about the things we know are bad. The more than 230 AZA-accredited zoos and aquariums in the United States should inform the public about the plight of tens of thousands of animals currently living in more than 2000 roadside zoos, pseudo sanctuaries, and unaccredited aquariums. For the most part, these animals are confined to impoverished conditions.

We should blur the lines of professional organizations as soon as possible and actively join the animal welfare community, the animal protection community, and the animal ethics community. The DZS changed its Center for Zoo Animal Welfare to the Center for Zoo and Aquarium Animal Welfare and Ethics. Animal ethics should be central and primary to all our considerations, as both empirical knowledge and ethical reflection are necessary to understand how to meet the needs of animals (Fraser, Citation1999).

We could simultaneously be sanctuaries for humans and nonhuman animals. We invest in the wild, but our conservation work means nothing to the individual captive animals who live in our zoos and aquariums unless they are sanctuaries that are safe and fulfilling environments. The animals’ quality of life should come first as we exemplify what it means to be humane. Without that as a foundation, we have little moral standing.

So, are we centers of great care, conservation, science, and education where animals thrive and not just survive? Are we centers of compassion and rescue? Or as some critics continue to assert, are we centers of confinement and cruelty where animals might suffer? We have to answer these questions with science, common sense, and actions. We need honest answers and clear, compassionate solutions.

References

- Campbell-Palmer, R., & Rosell, F. (2017). olfactory behavior in zoo animals. In B. L. Nielsen (Ed.), Olfaction in animal behaviour and welfare (pp. 176–188). Boston, MA: CABI.

- Carter, S., & Kagan, R. (2010). Management of ‘surplus’ animals. In D. G. Kleinman, K. V. Thompson, & C. Kirk Baer (Eds.), Wild mammals in captivity: Principles and techniques for zoo management (2nd ed., pp. 263–267). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Cheney, D., & Seyfarth, R. (1992). How monkeys see the world. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Fraser, D. (1999). Animal ethics and animal welfare science: Bridging the two cultures. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 65, 171–189.

- Gruen, L. (2014). Dignity, captivity, and an ethics of sight. In L. Gruen (Ed.), The ehics of captivity (pp. 231–247). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Gubernick, L. (2000, October 27). Where the Wild Things Aren’t. Retrieved from https://wsj.com/articles/SB972616827858145895.

- Hornaday, W. T. (1913). Popular official guide to the New York zoological park. New York, NY: New York Zoological Society.

- Hosey, G., Melfi, V., Formella, I., Ward, S. J., Tokarski, M., Brunger, D., … Hill, S. P. (2016). Is wounding aggression in zoo-housed chimpanzees and ring tailed lemurs related to zoo visitor numbers? Zoo Biology, 35(3), 205–209.

- Kagan, R. (2017). Sanctuaries: Zoos of the future. In J. Donahue (Ed.), Increasing legal rights for zoo animals: Justice on the ark (pp. 140–150). Lanham, Md: Lexington Books.

- Kagan, R., Carter, S., & Allard, S. (2015). A universal framework for exotic animal welfare. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 18(Suppl 1), S1–S10.

- Kagan, R., & Veasey, J. (2010). Challenges of zoo animal welfare. In D. G. Kleinman, K. V. Thompson, & C. Kirk Baer (Eds.), Wild mammals in captivity: Principles and techniques for zoo management (2nd ed., pp. 11–21). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Malamud, R. (1998). Reading zoos: Representations of animals and captivity. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Morgan, K. N., & Tromborg, C. T. (2007). Sources of stress in captivity. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 102(3–4), 262–302.

- Orban, D. A., Soltis, J., Perkins, L., & Mellen, J. D. (2017). Sound at the zoo: Using animal monitoring, sound measurement, and noise reduction in zoo animal management. Zoo Biology, 36(3), 231–236.

- Ozella, L., Anfossi, L., Di Nardo, F., & Pessani, D. (2015). Effect of weather conditions and presence of visitors on adrenocortical activity in captive African penguins (Spheniscus demersus). General and Comparative Endocrinology, 242, 49–58.

- Sherwen, S. L., Magrath, M. J., Butler, K. L., & Hemsworth, P. H. (2015). Little penguins, Eudyptula minor, show increased avoidance, aggression and vigilance in response to zoo visitors. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 168, 71–76.

- Young, T., Finegan, E., & Brown, R. D. (2013). Effects of summer microclimates on behavior of lions and tigers in zoos. International Journal of Biometeorology, 57(3), 381–390.

Appendix.

Zoo welfare exercise

This exercise allows subjective comparisons of quality of life in the wild to the quality life in a zoo for individual animals. The variables are broad determinants of the quality of life. The goal is to consider physical and social environments that affect the well being of individual animals. The final score is a broad indicator of the relative quality of life for an animal in the wild versus an animal in a zoo and may provide insight into changes that need to be made.

Rules:

The exercise is played with seven major elements. No side can get a score of more than 4 in any one area. Although it is subjective and arbitrary to weigh each variable equally, one could develop weightings specific to a species or determine a different maximum number per criteria, depending on a species’ behavioral ecology. Each species and each individual are different—an obvious but not always acknowledged consideration!

Physical/social environmental variables should be addressed both in quantity and quality as appropriate. Players need to be cautious when making assumptions about an animal’s cognitive/emotional abilities, awareness, or sensitivity.

Explanation and examples of variables to consider follow. Choice and control should be considered with all of the variables. They essentially cover the major conditions that ultimately affect things like stress, boredom, and “happiness.” We need to differentiate between characteristics like longevity and number of offspring, which are important to a species’ survival but may not be important to an individual animal’s welfare. Great apes, elephants, and marine mammals are especially interesting models to test; it is more challenging to choose a species who we assume is “demanding” (complex needs) in their physical and social requirements.

The variables …

Food: Consider the amount, nutritional value, frequency and timing of feeding opportunities, variety and choice, behavioral components like the ability to forage, and the taste, texture, and presentation.

Physical environment: Consider the physical space including size, complexity, day/night differences, shelter, substrate, privacy, competition/displacement, aquatic/terrestrial/aerial/subterranean appropriateness, barriers, temperature/weather, and olfactory environment.

Water: Consider the amount, quality (pollution, pH, oxygen), availability and access, temperature, and the ability as a life support medium (size and quality).

Predation: Are you predator and/or prey? Are there predators? Is some predation pressure good? Is it bad to be a predator who cannot predate?

Social opportunities: Consider intraspecies cooperation/competition, interspecies cooperation/competition (including with humans), number and sex ratio of cohabitants, choice of cohabitants, and compatibility.

Reproductive opportunities: Consider choice of mate/partner, opportunities to breed (for dominant vs. subordinate individuals), opportunities to raise young, and compatibility.

Health/health care: Consider parasites, immunity, amount of medical attention (positive and negative impacts of preventive medicine), and proximity to infected/contagious neighbors.