ABSTRACT

In this cross-sectional study, we aimed to describe differences between India and the United States in public perceptions of free-roaming dogs and cats, concerns related to free-roaming animals, and preferred strategies for veterinary medical interventions and population management. Between August 2021 and February 2022, 498 individuals completed an online survey including 210 Indian respondents and 288 American respondents. Free-roaming dogs and cats were largely perceived as community animals among Indian respondents, with significantly more respondents indicating they should be allowed to roam freely compared with American respondents. Respondents from both countries were concerned about animal welfare, although Americans were significantly more likely to list animal welfare, public health and wildlife risks as significant concerns related to free-roaming cats and dogs. American respondents were also more likely to support adoption for sociable animals and euthanasia for unsociable animals, whereas Indian respondents were more likely to support spay/neuter, vaccinate and release strategies for both dogs and cats. Our findings speak to the importance of implementing tailored strategies for free-roaming cat and dog management based on local cultures and community perceptions of free-roaming animals.

Introduction

Dog and cat populations vary drastically between countries, including differences in the number of unowned animals, owned pets with free outdoor access and owned pets that live exclusively in households. In India, an estimated 34% and 20% of people own a pet dog or cat, respectively (Rakuten Insight, Citation2021), while in the United States (US), 45% of households are estimated to own a dog (62 million households) and 26% are estimated to own cats (37 million households) (American Veterinary Medical Association AVMA, Citation2022).

In both countries, there are also large free-roaming populations of dogs and cats, which can include unowned or owned animals with free outdoor access. In India, the State of Pet Homelessness (SPH) Index estimates there are 62 million free-roaming dogs and 9.1 million free-roaming cats, with 68% of Indians reported to see a stray/street cat and 77% see a stray/street dog at least once per week (Mars Petcare, Citation2023). In the US there are 1.3 million free-roaming dogs and 41 million free-roaming cats as of 2021 (Mars Petcare, Citation2023). According to the SPH Index, 28% of the US population report seeing a stray/street dog at least once a week (Mars Petcare, Citation2023), although stray dog populations vary regionally with southern and western regions of the US having higher populations (Shelter Animal Count, Citation2023). One note of caution is that the SPH Index statistics were reported based on “more than 200 global and local data sources” (Mars Petcare, Citation2023), however those sources are not themselves publicly available, and so the estimates may be prone to error.

Free-roaming dogs and cats can pose a threat to local environments and people. Findings from a recent literature review suggest that cats are very generalist predators which have been documented to predate many species, primarily birds, reptiles and mammals (Lepczyk et al., Citation2023). Dogs can also harass or predate wildlife and over-compete with native species (Young et al., Citation2011). Other potential risks of free-roaming cats and dogs include transmitting infectious pathogens such as rabies, parvovirus, and canine distemper virus (CDV) (Young et al., Citation2011). An especially important zoonotic disease is rabies, which the World Health Organization reports that more than 99% of human rabies cases worldwide are attributed to transmission from dogs, and in India, there are an estimated 18,000–20,000 human rabies deaths annually (World Health Organization, Citation2023). In the US in 2019, there were no reported rabies cases in humans (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2021), although among domestic animals, cats and dogs accounted for more than 80% of domestic rabies cases with 245 cases in cats and 66 cases in dogs (Ma et al., Citation2021). Diseases like toxoplasma can also be transmitted to humans and animals through contact with cats or their fecal matter (Frenkel & Ruiz, Citation1981; Karakavuk et al., Citation2021).

A small number of studies have investigated perceptions of free-roaming companion animals in India and the US, mostly focusing on dogs and cats. A study conducted in 2022 gathered data from 1141 households in Goa, India which showed the majority of respondents felt free-roaming dogs are a menace (57%), a nuisance (58%) and scary (60%) whilst also agreeing that free-roaming dogs are vulnerable (59%), belong in communities (66%) and have a right to live on the streets (53%) (Corfmat et al., Citation2021). Another study, from 2019, assessed the influence of demographic characteristics on knowledge, attitudes and behaviors toward free-roaming dogs in northern India. Respondents from households with low socioeconomic levels and those under the age of 35 years were more likely to consider free-roaming dogs as a societal problem, while males were more likely to consider free-roaming dogs as a threat to human health (Tiwari et al., Citation2019). In the US, a study of Ohio residents found 49% of respondents held positive or sympathetic views of free-roaming cats, while 32% expressed neutral perceptions and 29% expressed concerns or negative emotions related to free-roaming cats (e.g., dislike, anger) (Lord, Citation2008). A second study in Georgia, found 40% of survey respondents reported having at least one positive experience with a free-roaming cat, although 50% of the survey perceived feral cats as a nuisance and 65% believed that more effective management was required (Loyd & Hernandez, Citation2012). The survey design, however, limits data interpretation and studies have since reported greater support for nonlethal control methods (Wolf & Schaffner, Citation2019). Another perception study, relating to free-roaming dogs at reservations, highlighted community-centered strategies for managing dogs, focusing on culturally relevant education, better animal control, and improved veterinary access (Cardona et al., Citation2023), while research involving community cats has found the lack of ownership does not weaken the bond caregivers have with community cats, with “clear policy implications” to support programs like trap-neuter-release (TNR) (Neal & Wolf, Citation2023). Perceptions shape how a society approaches animal care and control (Serpell, Citation2004), making it important to investigate perceptions of free-roaming animals before employing animal control and medical care interventions to ensure they can be effectively implemented in to the community.

To the best of our knowledge, few studies have considered differences in perceptions of free-roaming animals across countries, primarily in Europe (Smith et al., Citation2022). Here, we investigate the perceptions of adult respondents from India and the US regarding the free-roaming dogs and cats living in or alongside their communities. We do this by investigating:

Differences in perceptions of and concerns related to free-roaming dogs and cats between adults in India and the US, including concerns related to animal health and welfare, human health, public disturbance and property damage.

The responsibility citizens of each country feel to care for free-roaming dogs and cats.

Perceptions of the role of nonprofits and governments in providing care or services to support the health and welfare of free-roaming dogs and cats.

Perceptions of the role of veterinarians in providing medical care, including vaccinations (e.g., rabies) and spay/neuter, to free-roaming animals.

Methods

Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of adults in India and the US online between August 2021 to February 2022 using snowball sampling. The survey was distributed in India via e-mail, social media, and text messages to animal welfare organizations and workers through the primary author’s India-based connections developed over years of field work with free-roaming animals in India. The survey was available in English, Hindi, and Bengali languages. In the US, the survey was distributed in English via social media, including Penn Vet, animal sheltering and animal welfare organization channels. In both India and the US, the social media posts were intended to advertise the survey to both animal welfare professionals and the broader public, with the survey link open to participation by anyone. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to starting the survey. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pennsylvania (protocol number 849,324).

Survey

The survey was developed primarily based on the first author’s experience working with free-roaming dogs and cats in India, and existing literature, in particular Volsche et al. (Citation2019). The survey was created to gather preliminary, exploratory data about differences in attitudes toward free-roaming animals between countries. The final survey consisted of 58 questions in three different sections. The first section collected demographic data, including age, gender, educational attainment, yearly household income (lakh or USD), pet ownership history and their previous experience caring for free-roaming animals. The second section focused on perceptions of free-roaming animals. Participants were asked to indicate how strongly they agreed with a series of statements concerning free-roaming animals on five-point scales from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (5), and to select all of their concerns about free-roaming animals from a provided list. The third section asked respondents to select strategies that they believed might be effective to reduce free-roaming dog and cat populations and to indicate who they felt was responsible for caring for free-roaming animals, including vaccinations, spay/neuter, and access to veterinary care for injured animals using binary responses. It should be noted that these responses reflect respondents’ beliefs of what may be effective in reducing free-roaming populations, but do not provide any information about the true effectiveness of each solution. We also examined perceptions of the roles of nonprofit organizations and veterinarians in caring for free-roaming dogs and cats. The survey was first created in English and then translated to Hindi and Bengali using Google Translate. The first author, proficient in all three languages, then reviewed the translated versions for accuracy. The survey was designed to be comparable between the countries, so the majority of the questions were identical for respondents from both countries, although there were a few country-specific questions based on common nomenclature. For example, in India, local stray dogs were referred to as “Indies” and cats were identified as either purebred or stray cats. In contrast, in the US, cats were identified as purebred, stray or feral such as domestic shorthair or domestic longhair, or as a rescue cat of any breed. We did not develop the questions to reflect distinct constructs or measurable subscales, so psychometric tests on the factor structure of the questionnaire were not conducted.

To reduce the risk of bots biasing the data by completing the survey, we screened all survey responses to identify duplicate IP addresses and then examined the duration of survey completion to ensure the survey was not completed very quickly (which may indicate a bot). Through this process, we identified very few duplicate IP addresses, all of which fell within the anticipated range of survey duration. The survey did not include reimbursement which may also increase the likelihood of bots completing the survey (Griffin et al., Citation2021).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics, v27. Pearson Chi Square tests were used to compare demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and pet ownership history, between respondents from India and the US. We also used Pearson Chi Square tests to compare respondents’ concerns about free-roaming animals, their perceptions of the most effective strategies for reducing free-roaming animal populations, and their perceptions of groups who are responsible for caring for free-roaming animals. Mann Whitney U tests were run to compare respondents’ perceptions of free-roaming animals between India and the US. p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Descriptive characteristics

660 respondents initiated the survey, although n = 145 participants were excluded as they did not complete the survey, n = 13 did not provide consent, n = 1 was under 18 years of age, n = 1 did not provide their age, and n = 2 did not provide their country, leaving a final sample of 498 individuals.

There were significant differences in the descriptive characteristics of the sample based on the respondents’ country of residence (). The sample included significantly more 18–24-year-old respondents from India and more respondents over the age of 45 in the US (X2 = 57.02, p < 0.001). There were also significantly more female and non-binary respondents from the US and more males from India (X2 = 19.12, p < 0.001), although females comprised more than 75% of the sample in both countries.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of the sample by country of residence (n = 498).

Pet ownership was significantly more common among American respondents (X2 = 55.45, p < 0.001), and of those who owned pets, American respondents were significantly more likely to own both cats and dogs compared with respondents from India (). Indian respondents were significantly more like to have cared for an injured free-roaming cat or dog (82.4% from India, 64.2% from the US, X2 = 53.32, p < 0.001) or had a free-roaming dog or cat spayed or neutered (51.0% from India, 37.5% from the US, X2 = 114.40, p < 0.001).

Perceptions of free-roaming animals

We saw significant differences in respondents’ perceptions of free-roaming animals between India and the US (). Respondents from India were significantly more likely to “strongly agree” that both free-roaming dogs and cats were community animals compared with respondents from America who reported median responses of “somewhat disagree” and “neither agree nor disagree,” respectively. Respondents from India also “strongly agreed” and “somewhat agreed” that free-roaming dogs and cats should be allowed to roam, whereas American respondents “strongly disagreed” and “somewhat disagreed,” respectively. Both groups of respondents did not agree with the sentiment that free-roaming dogs and cats have a good life on the streets, although to varying degrees. Indian respondents had a median response of “somewhat disagree” for both species, while respondents from the US had a median response of “strongly disagree” for dogs and “somewhat disagree” for cats.

Table 2. Differences in perceptions of free-roaming animals by country of residence based on Mann-Whitney U tests (n = 498).

Concerns related to free-roaming animals

Respondents from the US were consistently more likely to report concerns related to free-roaming animals, including the risk of spreading disease, exhibiting aggressive behavior, impacts on animal welfare, impacts on wildlife and damage to property (). For cats, respondents from the US were also more concerned about noise pollution due to intraspecific fighting. Conversely, 12.4% and 16.2% of respondents from India reported no concerns in relation to free-roaming dogs and cats, respectively. For both cats and dogs, we found a moderate positive correlation between respondents who were concerned about free-roaming animals spreading disease and exhibiting aggressive behavior (bite/scratch/attack/chase) ().

Table 3. Differences in concerns related to free-roaming animals based on country of residence (n = 498).

Table 4. Spearman’s correlation between respondent’s concerns related to free-roaming dogs and cats (n = 498).

Caring for free-roaming animal populations

Respondents from India were more likely to believe that it was the responsibility of local people, animal caregivers, and governments to vaccinate, spay/neuter and care for injured free-roaming animals, while 10% of American respondents versus 0.5% of Indian respondents saying that it was no one’s responsibility to care for free-roaming cats and dogs (). Across both countries, veterinarians were selected at the lowest rate as a group responsible for the care of free-roaming cats and dogs.

Table 5. Respondents’ perceptions of who is responsible for caring for free-roaming dogs and cats based on country of residence (n = 498).

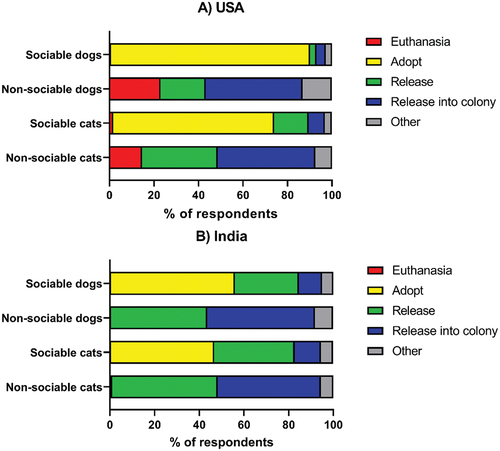

When asked about which strategies they perceived to be best to reduce free-roaming dog and cat populations, there were also differences between respondents based on their country of residence (X2 = 85.31, p < 0.001, X2 = 38.00, p < 0.001 for sociable dogs and cats, X2 = 66.51, p < 0.001, X2 = 27.22, p < 0.001 for non-sociable dogs and cats, ). Significantly more American respondents suggested that “spay/neuter, vaccinate and adopt” was the best strategy for both sociable dogs (89.5%,) and cats (72.4%), compared with 55.4% and 46.2% of Indian respondents. “Spay/neuter, vaccinate and release” (28.7% for dogs, 36.0% for cats) and “spay/neuter, vaccinate and release into dog or cat colonies” (10.4%, 11.8%) were significantly more common among Indian respondents compared with American respondents (2.8%, 15.4%, and 4.2%, 7.3%, respectively). Very few respondents in India (0.5%, 0.5%) or the US (0.7%, 1.7%) suggested that euthanasia was the best strategy to reduce sociable free-roaming dog and cat populations. For nonsocial dog and cat populations, significantly more American respondents indicated euthanasia was the best strategy (14.7%, 23.0%) compared with only 0.5% and 1.1% of Indian respondents, whereas “Spay/neuter, vaccinate and release” was selected significantly more as the best strategy for non-sociable dogs and cats among Indian respondents (43.1%, 47.2%) than American respondents (20.2%, 34.0%).

Discussion

Our study showed that Indian and American respondents had significantly diverging concerns related to free-roaming animals and beliefs about whether dogs and cats should be able to roam freely. To some extent, the differences in attitudes and beliefs mirror the differing distributions of free-roaming dogs and cats in each country. India, with a much larger number of dogs and cats living outside of human households (Mars Petcare, Citation2023), is potentially starting from a different place of material facts and normative attitudes. Existing policies, systems, and infrastructure for supporting free-roaming animals in each country are also likely to shape attitudes. In India, a shared commitment to free-roaming animals is written in law as a Fundamental Duty of Indian Citizens – with the Constitution of India stating that “It shall be the duty of every citizen of India [to] protect and improve the natural environment including forests, lakes, rivers and wild life, and to have compassion for living creatures” (Government of India, Citation2022). The cultural importance placed on compassion toward animals and the concept of ahimsa in Indian traditions may also contribute to respondents’ perspectives (Singh et al., Citation2015; Szűcs et al., Citation2012). The Animal Welfare Board of India (AWBI) also promotes Animal Birth Control (ABC) programs for humane sterilization and vaccination as outlined in the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act and “Animal Birth Control (Dogs) Rules.” The AWBI and other government bodies also promote the implementation of community-led initiatives, such as feeding and sheltering programs for free-roaming dogs and cats, and bars the unlawful removal of such animals from their home community areas (Government of India, Citation2012). In the US, the management of free-roaming dogs and cats is often guided by local animal control policies. For example, the use of TNR programs, which are more common for free-roaming cats than dog populations, may affect perceptions. The differing perceptions between countries highlights the essential role of considering local context when developing community-based and community-led solutions to One Health issues (discussed further in the Principles of Community Engagement (CDC, & ASTDR, Citation2011; Watson et al., Citationin press). Ethical community engagement is especially pertinent in the current era of global public health challenges and evolving discourse concerning the ethical, legal, and social responsibility of humans to nonhuman animals.

We found Indian respondents were more likely to consider free-roaming dogs and cats as community animals and believed they had the right to roam, whereas respondents from the US largely disagreed with these statements. Existing studies have also demonstrated that free-roaming dogs are often seen as a part of the community in India and many believe they have the right to roam (Corfmat et al., Citation2021). American studies have focused on perceptions of proposed interventions for free-roaming cats, with variable results. Loyd and Hernandez (Citation2012) found just over 25% of people agreed that unowned cats have the right to live in communities with 57% opposing trap-neuter-return (TNR) legislation, although the survey design may limit data interpretation (Wolf & Schaffner, Citation2019). Lord (Citation2008) found more than 75% of their study respondents agreed that TNR programs are a good way to manage free-roaming cats.

The welfare of free-roaming dogs and cats was a top concern in both countries, with both groups of respondents disagreeing that free-roaming dogs and cats have a good life on the streets. American respondents felt this was particularly true for free-roaming dogs. Previous research has also identified animal welfare as a key concern for free-roaming dogs and cats in both countries (Loyd & Hernandez, Citation2012; Tiwari et al., Citation2019). The difference in perceptions of free-roaming dog welfare between respondents from each country might be explained by the indicated normative values of both populations and the perceived right to roam freely reported by Indian respondents.

The spread of disease and public health issues associated with free-roaming animals, along with incidents such as biting, scratching, attacking, and chasing, were concerns shared by respondents in both India and the US. These issues were especially pronounced amongst American respondents, which could be due to an increased awareness of zoonotic disease and greater resources for public safety and disease prevention. However, this hypothesis warrants further investigation as previous research has identified key knowledge gaps in rabies awareness in both America (Palamar et al., Citation2013) and India (Herbert et al., Citation2012). The differing level of concern between countries is notably in contradiction to the prevalence of risks related to free-roaming animals since India has both a higher number of free-roaming animals and a higher risk of rabies (Radhakrishnan et al., Citation2020). While Indian respondents might have been expected to report heightened concern about the spread of disease compared with Americans, this was not reflected in respondents’ answers. It is possible that a lack of concern about the risk of disease could affect how individuals interact with free-roaming animals, perhaps placing them at a greater risk.

Wildlife impact was identified as a significant concern among respondents from the US, but not respondents from India. Protecting wildlife and supporting healthy ecosystems have also been listed as primary concerns in some previous American studies where upwards of 90% of respondents indicated these were very or extremely important issues for them in the management of unowned cats (Loyd & Hernandez, Citation2012). However, other studies suggest that the public believe outdoor cats should have the right to hunt (Wald et al., Citation2013). Studies in India have also found that local people are aware of the threats free-ranging dogs pose to other animals, including livestock and wildlife, and many develop negative perceptions as a result (Mahar et al., Citation2023). The difference between the respondents from the two countries in the present study could be the result of differing views about wildlife species, the importance of conservation, or more familiarity with ideas of ecological conservation in the US (Agrawal & Redford, Citation2009). Similarly, damage to property was a concern for free-roaming dogs and cats among American respondents, but not Indian respondents. Our study did not collect data on property ownership or urbanization, but studies have shown that respondents from rural, urban and suburban areas can report differing attitudes toward free-roaming animals (Lord, Citation2008).

Our study showed significant differences in preferred strategies for reducing free-roaming dog and cat populations between respondents from India and the US. The vast majority of American respondents advocated for “spay/neuter, vaccinate, and adopt” as the best strategy for managing both sociable dogs and cats. Despite being the preferred solution, many animal shelters in the US face overpopulation, often making it difficult to place all sociable animals (Shelter Animal Count, Citation2023). Previous research has also found the majority of Americans disagree that most free-roaming cats handled by animal agencies will be adopted (Lord, Citation2008). A comparatively smaller percentage of Indian respondents, 55% and 46%, support adoption of free-ranging dogs and cats as their preferred management strategy. More than a quarter of Indian respondents advocated for “spay/neuter, vaccinate, and release” for sociable dogs and 36.0% for sociable cats compared with only 3% and 15% of American respondents which reflects the differing perceptions of free-ranging animals between countries and species described above. About 10% of Indian respondents also supported the strategy of “spay/neuter, vaccinate, and release into dog or cat colonies,” indicating dedicated locations for free-roaming animals may be one acceptable strategy for some of the public. It is worth noting that both Indian and American respondents showed a strong aversion to the strategy of euthanasia to reduce sociable free-roaming dog and cat populations, with less than 1% of respondents in both countries considering euthanasia as the best strategy for sociable animals.

For non-sociable free-roaming dogs and cats, the proportion of American respondents suggesting euthanasia was notably higher with 14.7% and 23.0% suggesting it as the best approach, respectively. In stark contrast, only 0.5% and 1.1% of Indian respondents supported euthanasia as the best population control method, which mirrors previous research (Corfmat et al., Citation2021; Tiwari et al., Citation2019), with most preferring spay/neuter, vaccinate and release to the animal’s previous environment or into a colony. In the past, free-roaming cats in America were frequently targeted for extermination, either through trapping and euthanasia or through the use of poisons, but in recent years there has been a growing movement to adopt TNR as a more humane approach to free-roaming cat management although the issue remains contentious (Deak et al., Citation2019). In a study of perceptions of outdoor cats and management strategies in Florida, US, all stakeholders indicated a preference for non-lethal management strategies on average (Wald et al., Citation2013). Studies have also shown that population decreases are comparable for euthanasia, TNR, and even combination approaches, with euthanasia also having been shown to require more treatment effort and resources compared to TNR (Benka et al., Citation2022; Boone et al., Citation2019; Miller et al., Citation2014; Wolf & Hamilton, Citation2022). In India, animal birth control programs have also produced promising results with research finding dogs were less likely to contract diseases and disease prevalence reduced as the duration of the programs increased (Yoak et al., Citation2014). Overall, these findings reflect important differences in the perceptions of and management strategies for free-roaming dogs and cats in India and the US. Cultural norms and values, religious beliefs, historical attitudes and existing systems, infrastructure and policies toward animals can shape societal attitudes toward and beliefs regarding free-roaming animals (Serpell, Citation2004). Ultimately, effective and cost-efficient free-roaming animal population control requires engagement with all community stakeholders and creating acceptable consensus among interested parties (Hurley & Levy, Citation2022).

Our survey results revealed notable differences in viewpoints regarding the responsibility to care for free-roaming animals, including through vaccination, spay/neuter, and attending to injured animals. More Indian respondents believed that local people, animal caregivers, and governments were responsible for the care of free-roaming animals which suggests a collective sense of responsibility and a shared commitment to include free-roaming animals in Indian society that map to norms of collective duty (Lamb, Citation2005) and more-than-human responsibilities (Franklin & Franklin, Citation2017; Srinivasan & Srinivasan, Citation2019). As responsibility and community involvement with free-roaming dogs and cats are on-the-ground realities in India, collaboration between local communities, animal caregivers, veterinary doctors, and governments can also contribute to effective animal welfare programs. Notably, in both India and the United States, veterinarians were seen by respondents as the least responsible (as compared to communities, caregivers, NGOs, and governments) for free-roaming animals. This presents an area deserving of further study.

Further, only one Indian respondent indicated that it was no one’s responsibility to care for free-roaming cats and dogs compared with approximately 10% of American respondents. America has a strong tradition of individualism compared with modern India where until recently collectivism was more dominant. Previous research has linked increased individualism with lower cooperation with public health measures (Maaravi et al., Citation2021), meaning the difference in perceptions could have implications for the success of animal welfare policies and initiatives. Considering approaches used for other public health issues that are similarly impacted by individualism and collectivism (e.g., policies related to medical and environmental services and regulation) could help when designing programs for the management of free-roaming animals in each country.

Indian and American respondents also differed in their involvement in caring for injured free-roaming dogs or cats. A significantly higher proportion of Indian respondents reported caring for an injured free-roaming cat or dog and having a free-roaming dog or cat spayed or neutered compared to their American counterparts. Indian respondents likely had more exposure to free-roaming dogs and increased opportunities to interact and intervene given India has a larger proportion of free-roaming dogs than the US (Mars Petcare, Citation2023).

Overall, our study presents differences in perceptions between Indian and American respondents regarding free-roaming animals that could be attributable to a variety of causes, including prevalence of such populations, opportunities to interact and care, existing systems of infrastructure, beliefs about community and individual responsibility, and positions about the value of animals and their presence and role in different areas of society. Investigating these causes in greater detail, and how they relate to perceptions in different countries and contexts could help drive more effective approaches and programs for the care of free-roaming animals.

Limitations

Despite the valuable insights provided by this research study, it is important to acknowledge several limitations. The study focused solely on Indian and American respondents but did not ask for more specifics of geographic location. As both countries have diverse populations across vast territories, caution should be exercised when generalizing the results to different regions. The study also relied on self-reported data, which may be subject to response biases or inaccuracies.

There was an overrepresentation of female respondents from both countries. It has been previously documented that women are more likely than men to participate in animal-related research surveys (De Ruyver et al., Citation2021), although it is also possible that women’s potentially stronger attachment to animals (Herzog, Citation2007), their increased involvement in animal volunteering (Neumann, Citation2010), or the use of convenience sampling, through animal-involved and veterinary-adjacent channels, may have biased the study population. Future surveys could specifically ask about respondent experience or involvement with animal organizations, along with other expanded demographic details like regional information. Such information does not appear to be available in India. Although the results may be less generalizable to the broader populations, they may still reflect the beliefs of those involved in animal care.

The respondents also had contrasting pet ownership patterns, which may reflect differing population compositions between India and the US and could impact survey responses. Most respondents in both countries owned pets (likely due to the use of convenience sampling and the respondents’ educational profiles), although a much larger percentage of Indian respondents did not. The lower rates of pet ownership in India may be due to differing perceptions of the roles of dogs in India, although these perceptions appear to be changing (Volsche et al., Citation2019), or due to respondents regularly interacting with free-roaming dogs and cats which could provide a meaningful human-animal relationship similar to pet ownership (Corfmat et al., Citation2021).

A substantial proportion of the respondents had attained higher education, with 47.2% having postgraduate or professional degrees, which is not reflective of the general population in either country. Previous studies, specifically in the US, have indicated that certain demographic groups demonstrate a higher level of concern for animal well-being. Specifically, women, individuals facing economic hardship, those with limited educational attainment, and younger or middle-aged individuals have shown greater interest in the welfare of animals (Kendall et al., Citation2006). Future research should address these limitations by conducting comparative studies involving a wider range of countries, cultures and respondent demographics, and employing more robust research designs including random sampling frameworks or statistical matching techniques, such as propensity score matching, to provide comparable groups of respondents across countries.

While we tried to control for differences in cultural references and translation, phrasing of questions may have caused respondents to interpret the questions differently. One example is the use of the word “colony” to indicate a group of free-roaming animals cared for by community members. This word is commonly used in India for a residential housing complex for humans, but in the US could have been misinterpreted as sanctuary type housing for animals. Another example is the word “feral” which can impact public perceptions of animals. For example, in a New Zealand study, cat owners perceived the use of nonlethal population control methods as more acceptable for stray cats relative to feral cats (Farnworth et al., Citation2011). Additionally, the word “sociable” can be expected to vary and our survey did not include a specific definition of sociable versus non-sociable. Lastly, respondents may also have had varying definitions of what constitutes a “good life” or a “community animal,” and different interpretations of who is responsible for caring for free-roaming animals based on legislation and local norms or their preferences.

Conclusion

Our study describes the differences in attitudes toward free-roaming dogs and cats between Indian and American respondents. We found Indian respondents were much more likely to view free-roaming animals as community members with the right to roam. Respondents from both countries were concerned about the welfare of free-roaming animals, though more Americans perceived the public health and wildlife risks of free-roaming animals as significant concerns. Respondents also differed in their perceptions of population control strategies, with more American respondents supporting euthanasia for unsociable animals than Indian respondents, and personal versus governmental responsibilities for free-ranging animals. By recognizing and responding to global, regional and local variations in perceptions of free-roaming animals, policymakers, veterinarians, and animal welfare organizations can develop more context-specific and effective approaches for improving the well-being of free-roaming animals, promoting public health, and reducing human-animal conflicts.

Survey Combined.pdf

Download PDF (2.5 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10888705.2024.2374078

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agrawal, A., & Redford, K. (2009). Conservation and displacement: An overview. Conservation and Society, 7(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.54790

- American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). (2022). AVMA pet ownership and demographics sourcebook. Retrieved March 17, 2023, from https://ebusiness.avma.org/files/ProductDownloads/eco-pet-demographic-report-22-toc-introduction.pdf

- Benka, V. A., Boone, J. D., Miller, P. S., Briggs, J. R., Anderson, A. M., Slootmaker, C., Slater, M., Levy, J. K., Nutter, F. B., & Zawistowski, S. (2022). Guidance for management of free-roaming community cats: A bioeconomic analysis. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 24(10), 975–985. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098612X211055685

- Boone, J. D., Miller, P. S., Briggs, J. R., Benka, V. A., Lawler, D. F., Slater, M., Levy, J. K., & Zawistowski, S. (2019). A long-term lens: Cumulative impacts of free-roaming cat management strategy and intensity on preventable cat mortalities. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 6, 238. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2019.00238

- Cardona, A., Hawes, S. M., Cull, J., Connolly, K., O’Reilly, K. M., Moss, L. R., Bexell, S. M., Yellow Bird, M., & Morris, K. N. (2023). Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara nation perspectives on Rez Dogs on the Fort Berthold reservation in North Dakota, USA. Animals, 13(8), 1422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13081422

- CDC, & ASTDR. (2011). Principles of community engagement. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Human rabies surveillance. Retrieved April 29, from https://www.cdc.gov/rabies/location/usa/surveillance/human_rabies.html#:~:text=Cases%20of%20human%20rabies%20cases,the%20U.S.%20and%20its%20territories

- Corfmat, J., Gibson, A., Mellanby, R., Watson, W., Appupillai, M., Yale, G., Gamble, L., & Mazeri, S. (2021). Community attitudes and perceptions towards free-roaming dogs in Goa, India. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 26(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888705.2021.2014839

- De Ruyver, C., Abatih, E., Dalla Villa, P., Peeters, E. H., Clements, J., Dufau, A., & Moons, C. P. (2021). Public opinions on seven different stray cat population management scenarios in Flanders, Belgium. Research in Veterinary Science, 136, 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2021.02.025

- Deak, B. P., Ostendorf, B., Taggart, D. A., Peacock, D. E., & Bardsley, D. K. (2019). The significance of social perceptions in implementing successful feral cat management strategies: A global review. Animals, 9(9), 617. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9090617

- Farnworth, M. J., Campbell, J., & Adams, N. J. (2011). What’s in a name? Perceptions of stray and feral cat welfare and control in Aotearoa, New Zealand. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 14(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888705.2011.527604

- Franklin, A., & Franklin, A. (2017). The more-than-human city. The Sociological Review, 65(2), 202–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12396

- Frenkel, J., & Ruiz, A. (1981). Endemicity of toxoplasmosis in Costa Rica: Transmission between cats, soil, intermediate hosts and humans. American Journal of Epidemiology, 113(3), 254–269. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113095

- Government of India. (2012). Government guidelines on feeding/vaccination/Sterilization of stray dogs. Retrieved April 30, 2024, from https://iitrpr.ac.in/awc/assets/files/Guidlines.pdf

- Government of India. (2022). Constitution of India. Retrieved September 9, 2023, from https://legislative.gov.in/constitution-of-india

- Griffin, M., Martino, R. J., LoSchiavo, C., Comer-Carruthers, C., Krause, K. D., Stults, C. B., & Halkitis, P. N. (2021). Ensuring survey research data integrity in the era of internet bots. Quality & Quantity, 56(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01252-1

- Herbert, M., Basha, R., & Thangaraj, S. (2012). Community perception regarding rabies prevention and stray dog control in urban slums in India. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 5(6), 374–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2012.05.002

- Herzog, H. A. (2007). Gender differences in human–animal interactions: A review [Report]. Anthrozoös, 20(1), 7–21. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279307780216687

- Hurley, K. F., & Levy, J. K. (2022). Rethinking the animal shelter’s role in free-roaming cat management. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 9, 183. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2022.847081

- Karakavuk, M., Can, H., Selim, N., Yeşilsiraz, B., Atlı, E., Şahar, E. A., Demir, F., Gül, A., Özdemir, H. G., Alan, N., Yalçın, M., Özkurt, O., Aras, M., Çelik, T., Can, Ş., Değirmenci Döşkaya, A., Gürüz, A. Y., & Döşkaya, M. (2021). Investigation of the role of stray cats for transmission of toxoplasmosis to humans and animals living in İzmir, Turkey. The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries, 15(1), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.13932

- Kendall, H. A., Lobao, L. M., & Sharp, J. S. (2006). Public concern with animal well-being: Place, social structural location, and individual Experience*. Rural Sociology, 71(3), 399–428. https://doi.org/10.1526/003601106778070617

- Lamb, S. (2005). Cultural and moral values surrounding care and (In)dependence in late life: Reflections from India in an era of global modernity. Care Management Journals, 6(2), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1891/cmaj.6.2.80

- Lepczyk, C. A., Fantle-Lepczyk, J. E., Dunham, K. D., Bonnaud, E., Lindner, J., Doherty, T. S., & Woinarski, J. C. (2023). A global synthesis and assessment of free-ranging domestic cat diet. Nature Communications, 14(1), 7809. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-42766-6

- Lord, L. K. (2008). Attitudes toward and perceptions of free-roaming cats among individuals living in Ohio. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 232(8), 1159–1167. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.232.8.1159

- Loyd, K. A. T., & Hernandez, S. M. (2012). Public perceptions of domestic cats and preferences for feral cat management in the southeastern United States. Anthrozoös, 25(3), 337–351. https://doi.org/10.2752/175303712X13403555186299

- Ma, X., Monroe, B. P., Wallace, R. M., Orciari, L. A., Gigante, C. M., Kirby, J. D., Chipman, R. B., Fehlner-Gardiner, C., Cedillo, V. G., Petersen, B. W., Olson, V., & Bonwitt, J. (2021). Rabies surveillance in the United States during 2019. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 258(11), 1205–1220. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.258.11.1205

- Maaravi, Y., Levy, A., Gur, T., Confino, D., & Segal, S. (2021). “The tragedy of the commons”: How individualism and collectivism affected the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 627559. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.627559

- Mahar, N., Habib, B., & Hussain, S. (2023). Do we need to unfriend a few friends? Free-ranging dogs affect wildlife and pastoralists in the Indian Trans-Himalaya. Animal Conservation. https://doi.org/10.1111/acv.12876

- Mars Petcare. (2023). State of pet homelessness index. Retrieved September 8, 2023, from https://stateofpethomelessness.com/

- Miller, P. S., Boone, J. D., Briggs, J. R., Lawler, D. F., Levy, J. K., Nutter, F. B., Slater, M., Zawistowski, S., & Allen, B. L. (2014). Simulating free-roaming cat population management options in open demographic environments. PLOS ONE, 9(11), e113553. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0113553

- Neal, S. M., & Wolf, P. J. (2023). A cat is a cat: Attachment to community cats transcends ownership status. Journal of Shelter Medicine and Community Animal Health, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.56771/jsmcah.v2.62

- Neumann, S. L. (2010). Animal welfare volunteers: Who are they and why do they do what they do? Anthrozoös, 23(4), 351–364. https://doi.org/10.2752/175303710X12750451259372

- Palamar, M. B., Peterson, M. N., Deperno, C. S., & Correa, M. T. (2013). Assessing rabies knowledge and perceptions among ethnic minorities in Greensboro, North Carolina. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 77(7), 1321–1326. https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.593

- Radhakrishnan, S., Vanak, A. T., Nouvellet, P., & Donnelly, C. A. (2020). Rabies as a public health concern in India—A historical perspective. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 5(4), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed5040162

- Rakuten Insight. (2021). Pet ownership in Asia. Retrieved September 8, 2023, from https://insight.rakuten.com/pet-ownership-in-asia/

- Serpell, J. A. (2004). Factors influencing human attitudes to animals and their welfare. Animal Welfare, 13(S1), S145–S151. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0962728600014500

- Shelter Animal Count. (2023). Shelter animal count - the national database. Retrieved September 9, 2023, from https://www.shelteranimalscount.org

- Singh, J., Nagai, K., Jones, K., Landry, D., Mattfeld, M., Rooney, C., Sleigh, C., & Singh, J. (2015). Gandhi’s animal experiments. Cosmopolitan Animals, 120–132. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137376282_9

- Smith, L. M., Quinnell, R., Munteanu, A., Hartmann, S., Dalla Villa, P., Collins, L., & Olsson, I. A. S. (2022). Attitudes towards free-roaming dogs and dog ownership practices in Bulgaria, Italy, and Ukraine. PLOS ONE, 17(3), e0252368. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252368

- Srinivasan, K., & Srinivasan, K. (2019). Remaking more‐than‐human society: Thought experiments on street dogs as “nature”. Transactions/, 44(2), 376–391. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12291

- Szűcs, E., Geers, R., Jezierski, T., Sossidou, E. N., & Broom, D. M. (2012). Animal welfare in different human cultures, traditions and religious faiths. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences, 25(11), 1499–1506. https://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.2012.r.02

- Tiwari, H. K., Robertson, I. D., O’Dea, M., Vanak, A. T., & Rupprecht, C. E. (2019). Knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) towards rabies and free roaming dogs (FRD) in Panchkula district of north India: A cross-sectional study of urban residents. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 13(4), e0007384. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007384

- Volsche, S., Mohan, M., Gray, P. B., & Rangaswamy, M. (2019). An exploration of attitudes toward dogs among college students in Bangalore, India. Animals (Basel), 9(8), 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9080514

- Wald, D. M., Jacobson, S. K., & Levy, J. K. (2013). Outdoor cats: Identifying differences between stakeholder beliefs, perceived impacts, risk and management. Biological Conservation, 167, 414–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2013.07.034

- Watson, B., Berliner, E., DeTar, L., McCobb, E., Frahm-Filles, W., Henry, E., King, E., Powell, L., Reinhard, C. L., & Stavisky, J. (in press). Principles of veterinary community engagement. Journal of Shelter Medicine and Community Animal Health.

- Wolf, P. J., & Hamilton, F. (2022). Managing free-roaming cats in US cities: An object lesson in public policy and citizen action. Journal of Urban Affairs, 44(2), 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2020.1742577

- Wolf, P. J., & Schaffner, J. E. (2019). The road to TNR: Examining trap-neuter-return through the lens of our evolving ethics. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 5, 341. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2018.00341

- World Health Organization. (2023). Rabies in India. Retrieved September 9, 2023, from https://www.who.int/india/health-topics/rabies

- Yoak, A. J., Reece, J. F., Gehrt, S. D., & Hamilton, I. M. (2014). Disease control through fertility control: Secondary benefits of animal birth control in Indian street dogs. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 113(1), 152–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2013.09.005

- Young, J. K., Olson, K. A., Reading, R. P., Amgalanbaatar, S., & Berger, J. (2011). Is wildlife going to the dogs? Impacts of feral and free-roaming dogs on wildlife populations. BioScience, 61(2), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2011.61.2.7