ABSTRACT

Since the end of the Cold War, the Arctic has transformed from a geopolitical buffer, to becoming a core national priority for the Arctic states, and a desirable playing field for non-Arctic actors. Geopolitical changes and a growing concern for the impacts of climate change have led to increased attention towards the Arctic region, which has prompted an extensive growth in the establishment of conferences attending to Arctic issues. Conferences are central meeting places for international and interdisciplinary cooperation, the exchange of ideas, and for deliberating the geopolitical structure of the Arctic. Yet, no systematic examination exists of the role conferences within the Arctic governance system. This article attends to the gap in the literature, by demonstrating how conferences supplement the work of the Arctic Council, regarding expanding the agenda, broadening stakeholder involvement, and improving communication and outreach.

Introduction

The Arctic has been described as a ‘zone of peace' (Young, Citation2011b), and the term ‘Arctic exceptionalism’ has been used to describe successful efforts to maintain cooperation and stability in the region (Exner-Pirot & Murray, Citation2017). However, despite the long track-record of peaceful interactions in the Arctic, and that the region has avoided spill-over from conflicts elsewhere (Byers, Citation2017; Hønneland & Østerud, Citation2014; Østhagen, Citation2016), it is not immune to geopolitical changes (Young, Citation2014). Following the 2004 Arctic Climate Impact Assessment, Young (Citation2009) postulated Arctic issues would take on a more global cast, that it would be harder to frame a policy agenda in Arctic-specific terms, and that the circle of actors considering themselves stakeholders and demanding a voice would expand. Today, the growing interest of ‘outsiders' to become involved in the region is powered by concerns over climate change, a desire to engage in Arctic environmental research, by prospects for new shipping routes, extracting natural resources (oil, gas, minerals, fish), and other economic opportunities (tourism, infrastructure projects) (See inter alia Moe & Stokke, Citation2019; Peng & Wegge, Citation2015; Solli et al., Citation2013; Stokke, Citation2014).

Increased attraction towards and activities in the Arctic have implications for the region’s governance system (Humrich, Citation2013). The Arctic governance architecture examined in this article is understood as the structure of organizations, institutions, arrangements, processes, and actors’ actions and interactions in the region. The Arctic Council, the principal intergovernmental forum for cooperation in the Arctic, is a key organization in this system. The Arctic Council was established in 1996 as a soft-law forum intended to promote peace and stability through cooperation among its members states – the United States, Russia, Canada, Iceland, Norway, Denmark/Greenland, Finland, and Sweden – and six Indigenous peoples’ organizations: the Aleut International Association, the Arctic Athabaskan Council, the Gwich’in Council International, the Inuit Circumpolar Council, the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North, and the Saami Council (Arctic Council, Citation1996). In addition, 13 non-Arctic states and 25 organizations have been granted observer status as of 2020. As a consensus-based organization, the Arctic Council's autonomy is restricted by the sovereign member states. It has no programming budget, and cannot implement or enforce guidelines, assessments, or recommendations (Arctic Council, Citation2018). Moreover, globalizing forces have led to pressure for re-examining the role of the Arctic Council in handling affairs in a more complex governance setting (Young, Citation2019).

The question of who should be invited to negotiations and be responsible for agenda setting is contested, both politically and within academia (Nord, Citation2010, pp. 825–826). The issue of legitimate actors ties to the broader understanding of the Arctic – whether a traditional geopolitical narrative is applied, or whether one acquires a more heuristic understanding of the region as a global sphere (Keil & Knecht, Citation2017, p. 5). Those adhering to the geopolitical paradigm argue Arctic governance is historically, geographically, and legally bound by interactions between states with territory above the Arctic circle (Keil & Knecht, Citation2017, p. 8). Yet, the geopolitical order is increasingly challenged by non-Arctic states, sub-national entities, and non-state actors seeking to realize their interests in the region.

Accordingly, two challenges stand out regarding how to improve the fragmented Arctic governance structure: How to manage the growing number of agenda issues and emerging arrangements? How to incorporate the expanding stakeholder pool, and balance the interests of newcomers with those of sovereign Arctic rights-holders (Ingimundarson, Citation2014; Rossi, Citation2015; Young, Citation2012a; Citation2014)? While stakeholders are understood as a group of people bound together in different relationships by the jointness of their interests (Freeman, Citation2010, p. 5), rights-holders are local residents with stakes in the region beyond shared interests. This article considers interaction and dialogue through conferences as a solution to the challenges of incorporating the expanding agenda and stakeholder pool in the Arctic.

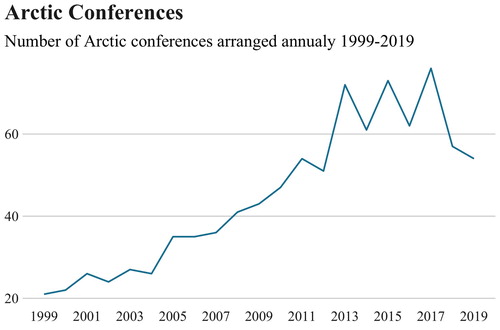

Conferences blur the line between governance and dialogue (Depledge & Dodds, Citation2017, p. 145), as they are not intergovernmental institutions or government forums, but can be parallel fora for discussions (Babin & Lasserre, Citation2019, p. 5). The literature on conferences is dispersed, and generally attends to the academic or educational value of conferences (Henderson, Citation2015; Hickson, Citation2006). Particularly, despite the number of Arctic conferences arranged annually – growing from around 20 arenas in 2000–70–80 conferences on Arctic issues since 2013 (see ) – the significance of these fora remains understudied in the Arctic governance literature (Depledge & Dodds, Citation2017, p. 145). This article attends to the gap in the literature by examining the functions of conferences, and from the identified challenges within Arctic governance answers the following research question: What are the contributions of conferences within Arctic governance, for managing the expanding agenda and incorporating new stakeholders? While the Arctic governance structure has expanded with several components since the 1990s, this article focuses on conferences as supplements to the Arctic Council. This analysis is conducted based on an in-depth examination of the two largest sites for international dialogue in the region: the Arctic Frontiers and the Arctic Circle Assembly.

Theory, methods and cases

Conceptual framework: governance and regime theory

Governance encompasses multiple dimensions and has diverse meanings (Rhodes, Citation1996), and conceptualizing governanceis no straight-forward endeavor. At the most general level, it entails efforts to solve collective problems, and to make good decisions for society. According to Young (Citation1997), ‘governance arises as a matter of public concern whenever the members of a social group find that they are interdependent' (p. 3). Governance is in this article understood as the process of interaction and decision-making among actors involved in a collective problem that lead to the creation, reinforcement, or reproduction of social norms and institutions (Hufty, Citation2011, p. 405). Governance is considered a dynamic process, evolving as new issues are introduced to the agenda. It comprises of a broad specter of interdependent actors who interact through network configurations to manage their common affairs. Lastly, governance is understood as a system evolved around shared norms and agreed upon rules of conduct.

The Arctic governance system has been described as a ‘mosaic of issue-specific arrangements',‘regime complex', ‘governance complex' (Young, Citation2005, Citation2011b, Citation2012b), and a patchwork of formal and informal arrangements operating on different levels (Stokke, Citation2011). The Arctic regime complex proposed by Young is defined as ‘a set of distinct elements that deal with a range of related issues in a non-hierarchic but interlocking fashion' (Citation2012b, p. 173). Examples of such elements are the Polar Code, the North-East Atlantic Fisheries Commission, and the International Arctic Science Committee. This article examines conferences as components within the Arctic regime complex, operating between sovereign states’ rights and interests, and cooperative arrangements.

Regimes encompass governmental and non-governmental actors, who are in agreement that cooperation on behalf of their shared interests justifies accepting the regime’s procedures, principles, norms, and rules (Rosenau, Citation1992, p. 8). Regimes affect actor behavior by functioning as social institutions with recognized patterns of practice around which expectations converge (Young, Citation1982, p. 277). At the same time, norm-governed behavior is consistent with the pursuit of national interests, so states can use regimes to achieve their interests through transparency and information exchange (Haggard & Simmons, Citation1987, p. 492).

International governance, and the Arctic governance system, is best examined as a system of governance without government. In such a system, the management of common affairs is conducted as an interplay between public and private entities, formal institutions, and informal arrangements (Rhodes, Citation1996; Rosenau, Citation1992). In contrast to governmental hierarchical coordination, where authoritative decisions are made with claims to legitimacy, non-hierarchical coordination is based on voluntary commitment and compliance, and conflicts of interests are solved by negotiations (Börzel & Risse, Citation2010). Nonetheless, states are still significant actors, and governance without government is more likely to be effective when a strong state can ensure contributions from non-state actors (Börzel & Risse, Citation2010).

Nye defines power as ‘the ability to affect others to obtain the outcomes you want’, which can be done through threats of coercion, inducements, or attraction (Citation2008, p. 94). Soft power – the ability to shape the preferences of others – is particularly relevant in the Arctic, where there is no super-national authority to enforce compliance. From these characteristics, it is also important to recognize the sovereignty of nation states. For example, the Arctic Council does not act without government approval, and all decisions are taken by consensus among the member states, with involvement and consultation of the permanent participants (Arctic Council, Citation2018).

Research design and data collection

This article is a result of a qualitative case study of the Arctic Frontiers and Arctic Circle Assembly. The conferences were selected from a process of ‘casing' (Ragin, Citation1992, p. 218), mapping out the universe of ‘Arctic conferences'. An extensive database of conferences on Arctic issues has been constructed for the study by using online calendars of events, such as that of the Arctic Research Consortium of the United States, the Arctic Portal, the International Arctic Science Committee, UArctic, and websites of other Arctic organizations, institutions, and institutes. Readers can contact the author for the database with an overview of Arctic conferences. The Arctic Frontiers and Arctic Circle were selected as the main cases in the study for several reasons. First and foremost, because of their hybrid nature, combining policy, science, and business, which makes them interesting by virtue of the broad agenda and participation of international delegates from various affiliations. Oposed to science oriented arenas (e.g. the Arctic Science Summit Week), or policy forums, the two cases provides for the examination of how conferences can contribute to cross-sectional interplay.

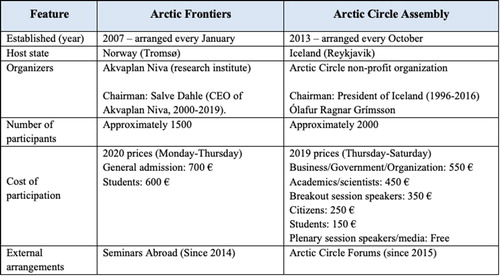

Secondly, as the largest international arenas on Arctic issues, being open to all interested participants (granted they have the financial resources to participate) – the two cases are interesting because of the large and varied participant pool. Thirdly, the conferences are reccurent events, which makes them relevant from the argument that cooperation is more likely to occur among actors who expect to meet again (Axelrod & Keohane, Citation1985). Fourthly, the two conferences are appealing by being competing arenas, thus introducing a marketplace element to the analysis. Lastly, while sharing a number of characteristics, the conferences are organized from different philosophies, which contributes to different outcomes within Arctic governance. The Arctic Frontiers is more in line with the geopolitical paradigm, while the Arctic Circle is organized from the outlook of the Arctic as a global commons. .

Table 1. List of informants to the study, by nationality and affiliation.

The main technique for data collection has been individual, semi-structured interviews with 25 informants. Participants were selected through purposeful sampling: people anticipated to be information-rich for the overall objective of the study. Informants include conference organizers, board members, speakers, and participants. Participants to the study are referred to by affiliation according to four categories: Policy; science/academia; business; others. When appropriate and necessary for the analysis, informants are also identified by nationality. The strategy of triangulation has been applied to gain the most comprehensive understanding of the cases, and the interviews have been complemented with participant observation and document analysis.

I attended the Arctic Frontiers in 2017, 2018, and 2019, and the Arctic Circle Assembly in 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019. Conference participation provided practical information about the arenas and following the conferences over a period of years allowed for observing agenda developments, and which issues remained salient. The document analysis was performed as a review of conference programs, the Arctic Frontiers from 2007 and the Arctic Circle from 2013, the Arctic policies of the Arctic states, and non-Arctic states who have produced strategies. Other written sources include governmental publications, white papers, reports, and political speeches.

Overview of the Arctic conference sphere and cases for analysis

International conferences in the 1970s and 1980s were largely issue-specific, often taking the form of annual science unions’ meetings. However, a window of opportunity opened for Arctic issues to rise on the international agenda in the late 1980s. The end of the Cold-War was a decisive political catalyst, coupled with the growing concern among scientists regarding pollution in the Arctic. Accordingly, geopolitical changes not only lead to the establishment of cooperative arrangements, such as the 1991 Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy, the International Arctic Science Committee, the Northern Forum, and the Conference of Parliamentarians of the Arctic, but also contributed to altering the conference landscape. Some of today’s main science conferences on Arctic issues emerged in the 1990s, including the International Congress of Arctic Social Sciences, and the Arctic Science Summit Week. Still, the number of Arctic conferences arranged annually remained relatively low.

However, a second window of opportunity – for the expansion of Arctic conferences – opened in the mid-2000s, with a growth in the number of arenas from 30–40 around 2007, to 72 in 2013 and peaking at 76 in 2017. This corresponds with Young’s ‘second state change’ in Arctic affairs, brought about by developments opening the Arctic to global concerns: the impacts of climate change and the spread of the socio-economic effects from globalization to the Arctic (Young, Citation2009, p. 427). Thus, with the Arctic moving from the periphery to the center of political attention, the main objective of conferences became to influence the decision-making process with scientific knowledge. Conferences established in the mid-2000s were both interdisciplinary – as different issue areas became more interlinked – and cross-sectoral – as the need for information exchange between stakeholders became more pressing. The Arctic Frontiers and Arctic Circle – as hybrid arenas combining policy, science and business – are therefore distinct from their predecessors. The following overview focuses on the characteristics of the two cases that are relevant for examining their functions within Arctic governance. .

The Arctic Frontiers

The Arctic Frontiers was intended as a national mechanism for bringing scientific knowledge into political processes, and facilitating cross-discipline collaboration. The initiative coincided agreeably with the Norwegian Government’s objective of pursuing an active High North strategy, and to position Norway on the international arena after the Cold War ended. Norway was the first Arctic state to issue a High North Strategy in 2006, followed by New Building Blocks in the North, in 2009, Norway’s Arctic Policy in 2014, and Norway’s Arctic Strategy – between geopolitics and social development in 2017 (Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Citation2014, Citation2017).

These documents illustrate the significance of the Arctic for Norway. Geopolitically, Arctic issues are important for cooperation with Russia, and economically, the region holds potential for extracting fish, oil and gas. The Norwegian government has particularly sought to ensure political stability and sustainable development while safe-guarding national interests, to involve Norwegian businesses in cooperation with Russia, and to present a coherent picture of Arctic issues nationally and internationally (Government of Norway, Citation2005). These objectives have been actively pursued and advanced through the Arctic Frontiers platform.

The Arctic Frontiers is constructed around the state-centered geopolitical paradigm, and the position that the Arctic states – those with the know-how – should be responsible for governing Arctic affairs. It is one of the more expensive Arctic conferences, and it emphasizes the primacy of the Arctic Eight, and Norway’s national agenda. It has therefore been described by informants as displaying closeness to the Arctic Council, with ‘members' and ‘observers’. Two factors contribute to the pronounced connection between the Arctic Council and the Arctic Frontiers, according to an Arctic Council official interviewed for the study. The logistical fact that the Arctic Council’s secretariat is located in Tromsø (since 2011), and the close involvement of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs became involved in the conference in 2014, and had a senior official employed in the secretariat from 2015 to 2018. Her job was to strengthen the policy section, and she worked with Seminars Abroad to promote the Arctic Frontiers internationally. Seminars Abroad are arrangements under the Arctic Frontiers organization in various European cities. These seminars have been arranged since 2014 with the purpose to brand the Arctic Frontiers internationally, make connections to the conference, and initiate collaboration for the partners. The involvement of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs must be seen in relation to the establishment of the Arctic Circle in 2013, which was considered a direct competitor to the Arctic Council and the Arctic Frontiers by both the organizers and the Norwegian government.

The Arctic Circle Assembly

The origin of the Arctic Circle Assembly was well-timed with Iceland’s changing position on the global arena. In 2006, the United States withdrew its military forces from Keflavik airbase, which, coupled with Russia resuming its long-range military aviation in 2007, forced the Icelandic government to rethink its strategic options (Ingimundarson, Citation2015; Wegge & Keil, Citation2018). The 2008 financial crisis further added a need for economic revitalization (Depledge & Dodds, Citation2017, p. 143). These factors, and the impacts of climate change, made the Arctic a key component of Iceland’s foreign policy, and of the government’s attempt to establish Iceland as a strategic hub in the North Atlantic.

The growing interests of non-Arctic states in the Arctic was also an important factor for Iceland's repositioning internationally. In 2012, China and Iceland signed a memorandum on Arctic science cooperation, and in 2013, Iceland became the first European state to sign a Free-Trade Agreement with China (Ingimundarson, Citation2015, p. 91). The process of deepening economic relations with China was promoted by Icelandic President (1996–2016), and initiator of the Arctic Circle Assembly, Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson (Depledge & Dodds, Citation2017, p. 143). The Arctic Circle's vision, so openly welcoming Asian states and industry interests, fostered skepticism among Arctic state actors. The uncertainties within the Arctic community around the time of the Arctic Circle’s establishment is illustrated by the informant working in the interface between policy and science cited below.

‘The Arctic Circle really began to take flight at a time when the Arctic Council was deadlocked over the question of whether to admit a bunch of new observers, in particular from Asia. And the President of Iceland, Grímsson, was very adept at saying to China and Japan and Korea and the others, who were waiting to see if they would be admitted as observers: ‘Come to the Arctic Circle. You are welcome. You will be treated as equals'. And, they did. Of course, they were also invited to the Arctic Frontiers, and a number of other places. Soon thereafter, China, Japan, South-Korea, and others were in fact admitted as observers.'

President Grímsson commonly describes the Assembly as an ‘open tent' or Medieval Square, and the agenda is developed as a democratic process, with breakout sessions constructed by participants and topics they bring with them, not by the organizers. Since 2015, the Arctic Circle organization has arranged Forums in nine countries in cooperation with the host-state government and research institutions.

In summary, the establishment of the Arctic Frontiers in 2007 and the Arctic Circle in 2013 should not be considered arbitrarily, but rather as initiatives designed to fill specific demands. The Arctic Frontiers was initiated based on a realization of the need for a mechanism bringing scientific knowledge into the decision-making process, and to secure knowledge based social, economic and business development. The creation of the Arctic Circle was expedient in relation to non-Arctic states’ growing interest for engagement in the region. The Arctic Frontiers and the Arctic Circle should also be considered two different models for conference organizing, respectively top-down and bottom-up.

Results: conferences as supplements to the Arctic Council

The Arctic Council has since its establishment contributed to the regional Arctic governance system by promoting peace and stability through cooperation among its member states, Indigenous people’s organizations, and observer entities. The Working Groups and Task Forces have produced important scientific research. However, the Arctic Council’s agenda is limited, and the observer role cannot be expanded to entail the same rights as membership. Accordingly, the main identified gap in the Arctic governance architecture, and a general shortcoming of soft-law organizations, is the challenge of dealing with all issues, and involving all relevant stakeholders. From this, I argue the Arctic Council has reached a point of satiation, and the following discussion addresses three supplementing functions of conferences within Arctic governance.

Expanding the limited agenda

The Arctic Council is described as ‘a policy-shaping, rather than policy-making body' (Young, Citation2011a, p. 193), ‘a decision-preparing rather than a decision-taking institution' (Haftendorn, Citation2013, p. 38), and Ingimundarson (Citation2014) argues the Arctic Council is not a body of political authority. Nor was this the intention, as the Arctic Council was established as a forum to ‘provide a means for promoting cooperation, coordination, and interaction [- - - ] in particular issues of sustainable development and environmental protection in the Arctic' (Arctic Council, Citation1996). A footnote in the Ottawa Declaration states: ‘The Arctic Council should not deal with matters related to military security.' A government informant to the study describes how a lot of the Arctic Council’s success as a stability promoting organization rests on keeping security and military issues at arm’s length. It has made Russia an engaged actor, and enabled cooperation between the US and Russia.

Complex interdependence (Keohane & Nye, Citation2012) contributes to explaining the cooperative spirit in the Arctic, and how the region has avoided spill-over from conflicts elsewhere (Byers, Citation2017). Complex interdependence is characterized by state policies not being arranged in stable hierarchies; multiple channels of contact exist among societies; military force is largely irrelevant (Byers, Citation2017, p. 3; Keohane & Nye, Citation2012, 270). When Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, the US, EU, Canada, and other NATO allies responded with economic sanctions (Østhagen, Citation2014). However, Byers finds that international relations in the Arctic had achieved a state of complex interdependence, and was therefore not severely affected by the conflict (Byers, Citation2017, p. 20). The Arctic states have remained cooperative, largely due to common interests. This includes Russia, who also benefits from a stable and rules-based Arctic, in which to pursue socio-economic development. As noted by a conference organizer:

‘Maybe the best example is the Russian participation, not just at Arctic Circle, but in conferences in general. I think the fact that Russia and the Arctic neighbors continue to get along as well as we all do, given the circumstances, is really quite remarkable.'

The Arctic Frontiers is thematically oriented towards the Norwegian government’s priorities, in particular the longstanding interest in the oceans, but also energy related topics. This is evident when looking at the Arctic Frontiers’ titles, which from 2007 to 2020 have been The unlimited Arctic; Out of the blue; The age of the Arctic; Living in the High North; Arctic tipping points; Energies in the High North; Geopolitics and marine production in the changing Arctic; Humans in the Arctic; Climate and energy; Industry and environment; White space – blue future; Connecting the Arctic; Smart Arctic; the power of knowledge.

Regarding security, this topic is predominately approached through the science section, related to human, environmental, and food security. There is a total of 37 sessions from 2007 to 2019 with the word ‘security' in the title. Sparsely from 2007 to 2012, but the number increases from 2013. The science part of the 2013 conference was organized around three parallel sessions, including Geopolitics in a changing Arctic with three sub-sessions: Arctic security in a global context; New stakeholders and governance in the Arctic; The Arctic in a global energy picture. The former addressed how the Arctic states are in the process or redefining their interests and policies in the region, and what this means for Arctic security.

In 2014, the Humans in the Arctic conference attended to health, food and water security. The 2015 Climate and Energy and 2016 Industry and Environment conferences focused on the Arctic’s role in the global energy supply and security: renewable energy, societal aspects of Arctic energy activities, and oil and gas exploration. Through 2017–2019, security was also primarily addressed in terms of food and energy security. The 2019 conference included a day-long side event on Science Diplomacy and Security in the Arctic, focusing on the interplay between global geopolitics and what goes on in the Arctic. Topics addressed were East–West security, science as a venue for trust building, how to implement the Arctic Council’s Science Agreement, and US–China rivalry.

Through a discourse analysis of Arctic Circle programs, Johannsdottir and Cook (Citation2017) found a growing emphasis on energy, science, research, and security in the titles of plenary and breakout sessions from 2013–2016 (p. 278). The security-oriented sessions included geopolitical and military issues, human, social, and environmental security. In 2014 there was an Arctic security plenary session, in addition to four security-oriented breakout sessions, including one titled Military strategies and defense policies in, and impacts of recent crisis on, security of the Arctic. Noteworthy, in the aftermath of Russia’s annexation of Crimea in February/March that year. Other topics were geopolitics and regional dynamics in a global world, environmental and human security, local and regional security, and new security actors. In 2015, the Thematic Network on Geopolitics and Security arranged three breakout sessions on Military Presence, Defense and Security Policies of the Two Major Nuclear Powers; Security Policies, Defense Strategies, and Regional Security in the Arctic; Future Security of the Arctic – Resources, Energy, Environmental/Human Security. In 2016, there was also a plenary session titled Keeping Arctic water safe: International cooperation - safety, security and emergency preparedness organized by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Nord University.

The Munich Security Conference arranged an invitation-only Roundtable in Reykjavik before the 2017 Arctic Circle. Participants discussed the state of Arctic governance and cooperation, China’s economic investments in the Arctic, and how Russia’s building of military infrastructure should be interpreted (Munich Security Roundtable, Citation2017). At the main Assembly, a breakout session titled Arms race, arms control and disarmament in the Arctic – Russian-US dialogue goes straight to the core of issues that could not have been raised at the Arctic Council. In 2018, the University of Southern Denmark and University of Loughborough (UK) arranged a session on Arctic security trends and emerging issues, attending to Danish-Greenlandic relations and the impact of great power politics.

This overview demonstrates how, while the Arctic Council has been successful as a cooperative forum in the region, nation states are concerned about the geopolitical situation in the Arctic. This creates a need for a space to deliberate military and security issues. Conferences can provide such arenas, and consequently contribute to expanding the agenda within the Arctic governance system.

Broadening stakeholder involvement

The other limitation of the Arctic Council is involving the expanding stakeholder pool in the region, which has grown outside the range of the initial creators from 1996 (Graczyk & Koivurova, Citation2013). The Arctic is affected by the activities of non-Arctic actors, and there are issues the Arctic states cannot deal with alone (Young, Citation2014, p. 234). This necessitates involving non-Arctic states in discussions, in particularly regarding how to limit and mitigate the effects of climate change. However, Knecht (Citation2016) examines stakeholder participation in Arctic Council meetings, and finds that observers participation quotas are much lower than those of member states and permanent participants (p. 18). Babin and Lasserre analyze the participation of Asian states in the activities of the Arctic Council, and show these are ‘extremely weak and limited by a very restricted status' (Babin & Lasserre, Citation2019, p. 10). Thus, Rossi’s question of whether an alternative form of Arctic governance can emerge, from the inability of the status quo to satisfy expanding interests (Rossi, Citation2015, pp. 24–25), is compelling.

Yet, whether non-Arctic states should be more involved in Arctic affairs is a contested issue, and including the growing pool of interested stakeholders in a meaningful way while balancing their activities with the rights and interests of Arctic sovereigns and local communities, is challenging. Prior to the Arctic Council's ministerial meeting in Kiruna in May 2013, tensions arose among the Arctic states regarding how to deal with the observer candidatures of China, Japan, South-Korea, Singapore, India, and Italy. Canada and Russia particularly expressed reluctance, while the Nordic countries were more favorable (Lackenbauer, Citation2014). The sovereignty of the Arctic states and Indigenous peoples potentially being challenged, and the economic and military power of the expanding great power China, were sources of concern (Babin & Lasserre, Citation2019).

When the growing interest among Asian states to participate in Arctic affairs was coupled with the launch of the Arctic Circle Assembly in April 2013, as an ‘open tent' inviting all interested parties to participate in the Arctic dialogue (Grímsson, Citation2013), a second line of concern arose. If the Arctic Council did not accept the pending observers, they could not only develop their own competing forum (Manicom & Lackenbauer, Citation2013), but also utilize the platform provided by president Grímsson. Accepting Asian states into established institutions meant the Arctic Eight could remain in charge of cooperative structures and the framework for debate. As then Foreign Minister of Norway, Espen Barth Eide, stated in his opening speech at the Arctic Frontiers in January 2013:

‘We are happy that more people want to join our club, because this means that they are not starting another club, and that gives us some influence on what topics are discussed in relation to the Arctic' (Eide, Citation2013).

To that end, president Grímsson asserts that giving outside states the opportunity to be constructive partners in the region adds an element to the Arctic governance structure. To use the Arctic Circle platform, these states have to be transparent, which contributes to creating responsible stakeholders. By facilitating interaction and sharing of expertise and best-practices, conferences contribute to ameliorate the problem of limited information and lack of knowledge about others’ motives in the international system. Consequently, barriers to cooperation are reduced. The remainder of this section is devoted to two examples of non-Arctic states taking advantage of the conference platform.

Switzerland’s Arctic Council observer state candidature was pending for the ministerial meeting in Fairbanks 2017. Prior, the Swiss government considered it important to showcase Swiss’ interests, work, and engagement in the Arctic. The Arctic Circle in October 2016 was regarded a good opportunity to explain the link between Switzerland and the Arctic, and why Switzerland was a relevant stakeholder. Switzerland had a country presentation in the plenary program, a breakout session, and a large exhibition in the conference building. The Swiss Ministry of Foreign Affairs was also present at the 2017 Arctic Frontiers in January. According to a Senior Arctic Official: ‘The Swiss Arctic Circle 2016 presentation demonstrated to some who were not necessarily convinced that Switzerland was actually serious about this, and might have something to contribute to the Arctic Council.' Switzerland became an observer to the Arctic Council in May 2017. At the 2019 Arctic Circle Assembly, Swiss Ambassador Stefan Esterman spoke in the plenary session, on Switzerland’s connections to the Arctic, justifying its polar policy, and emphasizing scientific contributions to the Arctic Council’s working groups.

While Switzerland’s primary interest was to promote itself as a relevant Arctic stakeholder, the case of Scotland serves to illustrate different functions provided by the conference platform: seeking partnerships and positioning. From a geopolitical perspective, the Arctic region was considered one to which Scotland could form closer ties following the uncertainties after the UK’s decision to leave the EU in June 2016. As noted by an informant from the science community: ‘Scotland sees the opportunity to emerge as, and be perceived as, a ‘North-Atlantic country’. In the same way as the Faroe Islands, Greenland.'

In October 2016, Scotland’s First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, spoke at the Arctic Circle Assembly. She was distancing Scotland from the prevalent anti-globalizing forces in the UK, and proposing closer cooperation with Scotland's neighbors in the North Sea. The First Minister returned to the 2017 Assembly for a plenary Dialogue with Chairman Grímsson, and hosted an Arctic Circle Forum in Edinburg in November 2017, on common interests between Scotland and the Arctic. At the Forum, External Affairs Secretary Fiona Hyslop announced Scotland would be issuing an Arctic strategy.

‘Scotland is the closest neighbor to the Arctic states, and we have many shared interests and challenges, from renewable energy and climate change targets to social policies and improving connectivity. With the threat of a hard Brexit still possible, it is important we continue to work with our northern neighbors to build strong relationships. Our involvement with the Arctic Circle organization is an excellent opportunity to do this.' (Scottish Government, Citation2017)

This underlines the importance given to conference participation by the Scottish government. Conferences have aided the promotion of Scotland’s Arctic policy interests, as arenas to showcase their engagement and make connections. In broader terms, Scotland’s operations through the Arctic Circle illustrates a general function of the organization. Providing sub-national or regional entities the opportunity to enter Arctic cooperation and promote their interest, independently of the state or federal government.

Improving communication and outreach

The third challenge of the Arctic Council, which is described as the ‘unknown Council' by an academic informant, is communitcating to the broader public. One government affiliated informant accounts for the difficult position of the Arctic Council, as a closed club that needs to discuss things in private, while at the same time communicate contributions to regional development, especially the activities of the working groups. While the audience at conferences cannot be considered ‘the general public', utilizing these arenas is nonetheless a means for the Arctic Council to broaden its outreach. This section outlines the presence of the Arctic Council, in particular the working groups, at the Arctic Frontiers and Arctic Circle.

At the 2008 Arctic Frontiers, the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) Working Group presented results from the Assessment of the Oil and Gas Activities in the Arctic. The science program further included two sessions co-chaired by representatives from the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF), and Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment (PAME) working groups. At the 2014 conference, Humans in the Arctic, the Director of the Arctic Council secretariat, Magnus Jóhannesson, led a session on Arctic health issues, with speakers from AMAP and the Sustainable Development Working Group (SDWG). In 2015, the chair of the Arctic Council’s Senior Arctic Officials (SAOs) spoke in the policy opening session, and there was a session on the role of AMAP as an Arctic messenger. In 2016, a representative from the Emergency Prevention, Preparedness and Response (EPPR) Working Group addressed the SAR-agreement and oil-spill task forces.

The Russian SAO spoke in the opening session at the 2017 Arctic Frontiers, which also included a session on The Arctic Council’s Work on Oceans, with a keynote by the US Chair of the SAOs, Ambassador David Balton, and panelists from PAME, EPPR, the Task Force on Scientific Cooperation, and Japan’s Polar Ambassador representing the observer states. In 2018, the Arctic Frontiers included a session titled Can the Arctic Council model work for the Hindu Kush Himalayan Region, with the Canadian SAO, and representatives from AMAP and SDWG. Lastly, the chair of EPPR spoke at a 2019 event, on Improved safety and environmentally sound operations in the Arctic Ocean.

AMAP and EPPR are the most active working groups at the Arctic Frontiers, while the Arctic Circle has been attended frequently by CAFF, hosting thirteen breakout sessions over the six years the conference has been running, five of which together with PAME. Recurrent topics are Arctic biodiversity conservation, sustainability, and invasive alien species. In 2015, CAFF held a breakout session on Implementing the Recommendations of the Arctic Biodiversity Assessment. This illustrates the function conferences have for drawing attention to agreements and assessments. Another initiative by CAFF, repeated in 2017 and 2018, is breakout sessions on how to engage the youth in Arctic biodiversity.

‘Several of the plenaries have had the secretariat of CAFF or PAME be a facilitator or a speaker, which allows them to describe recent work products in a way that people sitting in the audience probably did not know about. So, yes, I think it is another way of getting information about the Arctic Council’s work out to a broader audience.'

Situating conferences within Arctic governance

The findings presented about the ways the Arctic Frontiers and Arctic Circle supplement the Arctic Council demonstrate how conferences are more than networking arenas. Conferences play a role in the Arctic governance architecture, and in the words of president Grímsson, can be a model of constructive cooperation for the global community. Firstly, conferences expand the agenda by providing platforms to address a wider range of topics – e.g. security and military issues – in the Arctic. This function is more prominent through the ‘open tent' at the Arctic Circle, where (breakout) sessions are constructed around participants’ proposals, than at the Arctic Frontiers, where the organizers control the program. At the same time, conferences contribute to maintaining the Arctic as a zone of peace, by facilitating dialogue and interaction among participants from within and outside the region. As such, conferences are arenas for the pursuit of soft power: the ability to shape the preferences of others by promoting interests, priorities, and viewpoints (Nye, Citation2008).

Secondly, the most significant supplementing function of conferences is providing a platform for non-Arctic states and non-state actors to have a voice and express their interests. As demonstrated, the geopolitical paradigm of the region is increasingly challenged by a heuristic view of the ‘global Arctic' (Keil & Knecht, Citation2017). This is not to say the group of outsider stakeholders should be entitled to an equal voice, the same rights, or corresponding governance power to that of sovereign Arctic states and local residents. However, the Arctic agenda has increasingly been merged with the global agenda – in particularly regarding political economy and challenges of climate change (Young, Citation2019) – and conferences contribute to elevating Arctic issues outside the region. How the Arctic community involves new stakeholders can impact international diplomatic relations, so it is necessary to engage emerging powers, such as China, in a constructive way. Accordingly, the political implications of economic interests in the Arctic opens a space for conferences within the governance structure, as arenas to include and educate non-Arctic actors, and to promote a balanced view of social and economic development with environmental protection and local community well-being.

Thirdly, the article has established how conferences are useful communication and information channels for those engaged in Arctic affairs. For one, they support the Arctic Council in disseminating its work. Additionally, the governance landscape is becoming increasingly complex, with a growing body of engaged entities. This means institutional branding becomes more important, to promote the one's work, and attract financial and human resources. To this end, conferences fill a necessitated space within Arctic governance, as arenas for role differentiation, and creation of synergies among engaged entities.

In addition to the general functions discussed above, the Arctic Frontiers and Arctic Circle can also constructively be viewed as complementing arenas within Arctic governance. The main function of the Arctic Frontiers is to preserve the established: science and research collaboration, and the advancement of knowledge-based policy making. Within the cooperative zone of peace, this is an important role for maintaining stability. It is necessary to have an arena where actors can gather to re-digest ideas and develop the conversation. The primary function of the Arctic Circle is providing a stage for new non-Arctic stakeholders. Asian states’ interests in global economic investments are expanding into the Arctic region, and the Arctic Circle contributes to these actors both having a voice and becoming educated about local conditions. Accordingly, the role of the Arctic Circle in creating educated and more responsible stakeholders is advantageous for the regional dialogue.

The examination of two similar, yet in many ways different, cases further illustrates challenges of soft-law conventions in general. For one, when initiatives launched at informal arenas that conflict with the interests of central stakeholders gain momentum outside the event. Moreover, while conferences do not provide direct governance influence, another concern is that facilitating an unfiltered stage for outsiders can be problematic, especially if the voices of non-Arctic and/or financially strong participants are privileged at the expense of Arctic rights holders’ perspectives and interests. By allowing non-Arctic representatives to present whatever they please, the message can be misrepresentative of Arctic communities. Thus, local residents and Indigenous peoples are potentially challenged by the elitist Arctic Frontiers, and the Arctic Circle, where dominating perspectives can be disconnected from Arctic sovereigns. The elite in the south and non-Arctic actors are moving to the north, while not always being attuned to local concerns. This contributes to the Arctic Frontiers and Arctic Circle not always being viewed in positive terms within the Arctic community.

Lastly, while more open than the Arctic Council, conferences are not town meetings. As pointed out by an informant from an American governance institution: ‘It’s not like anybody of the street can just walk in. It’s not completely democratic or transparent.' Conference participation is also a financial matter – which raises the question of who are given the opportunity to attend. Conferences tend to be dominated by actors with the most resources, strategic positions, and extensive networks. Organizations have to choose which delegates to send, and to which conferences. This is not an election process, which, if delegates represent a group or community's interests, poses a democratic challenge and underscores the elitist characteristic of these arenas.

Concluding remarks

It is becoming gradually more difficult to argue for Arctic exceptionalism, as the region is affected by, and reflects, global developments and power structures. The Arctic is resource abundant, and a geopolitical important zone for powerful states. This makes governing increasingly demanding, for example with regards to how the economic interests of outsiders clash with the political and strategic sovereignty concerns of the Arctic states. Still, Arctic cooperation has proved resistant to spill-over from conflicts elsewhere. It is a region characterized by joint efforts to solve common challenges, and the governance system remains a peaceful and stable structure.

The necessity of conferences is a contested issue. The elitist character of the two cases is a valid concern. Moreover, the Arctic Frontiers and Arctic Circle benefits non-Arctic state representatives who want to legitimize their presence in the region, and brand themselves as valuable stakeholders. In particular the Arctic Circle’s openness towards all who consider themselves stakeholders is not always welcomed by Arctic states, and is potentially disadvantageous for local communities. Some informants express concern with regards to non-Arctic country presentations at the expense of the time given to Arctic rights-holders. Others are troubled about the information communicated by non-Arctic actors being misinterpreted by other unexperienced participants, leading to false impressions about the region. Yet, despite these shortcomings, conferences are becoming as manifested as any other element within Arctic governance. The Arctic Frontiers and Arctic Circle Assembly each attract approximately 2000 people every year, who expect to meet to develop their networks and promote their work.

The article has demonstrated that conferences add a dimension to the work of the Arctic Council within Arctic governance. In particular, by expanding the agenda, providing a broader stakeholder pool a platform and the opportunity to enter Arctic cooperation, and by acting as communication and information channels. The format of the Arctic Circle and the Arctic Frontiers is a new phenomenon in terms of international cooperation, where participants are given the same right to participate, speak and ask questions, regardless of formal status – however, granted they have the financial resources to attend. As a supplement to intergovernmental cooperation, this model has the potential to enhance knowledge and boost collaboration among Arctic and non-Arctic actors engaged in the region. Conferences expand the structure of Arctic governance, if defined as a structure of cooperation and dialogue, and should be considered contributions to Young’s ‘regime complex' in the Arctic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Arctic Council. (1996). Declaration on the establishment of the Arctic Council. Ottawa, Canada.

- Arctic Council. (2018). The Arctic Council: A backgrounder. https://arctic-council

- Axelrod, R., & Keohane, R. O. (1985). Achieving cooperation under Anarchy: Strategies and institutions. World Politics, 38(1), 226–254. https://doi.org/10.2307/2010357

- Babin, J., & Lasserre, F. (2019). Asian states at the Arctic Council: Perceptions in Western states. Polar Geography, 43(3), 1–15. https://doi.org/1088937X.2019.1578290

- Börzel, T., & Risse, T. (2010). Governance without government. Can it work? Regulation and Governance, 4(2), 113–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2010.01076.x

- Byers, M. (2017). Crises and international cooperation: An Arctic case study. International Relations, 31(4), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117817735680

- Depledge, D., & Dodds, K. (2017). Bazaar governance: Situating the Arctic circle. In K. Keil, & S. Knecht (Eds.), Governing Arctic change (pp. 141–160). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Eide, E. B. (2013, January). “Opening Remarks at Arctic Frontiers: The Arctic - The New Cross- roads.” Speech at the Arctic Frontiers by then Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Espen Barth Eide. https://bit.ly/2vtz6H9

- Einarsdóttir, V. (2018, November). A New Model of Arctic Cooperation for the 21st Century. Journal of the North Atlantic and Arctic. https://jonaa.org/content/2018/10/19/a-new-model

- Exner-Pirot, H., & Murray, R. W. (2017). Regional order in the Arctic: Negotiated exceptionalism. Politik, 20(3), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.7146/politik.v20i3.97153

- Freeman, R. E. (2010). Managing for stakeholders: Trade-offs or value creation. Journal of Business Ethics, 96(S1), 7–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0935-5

- Government of Norway. (2005). Opportunities and challenges in the North. White Paper No. 30 (2004-2005).

- Graczyk, P., & Koivurova, T. (2013). A new era in the Arctic Council’s external relations? Broader 19 consequences of the Nuuk observer rules for Arctic governance. Polar Record, 50(254), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247412000824

- Grímsson, ÓR. (2013, April). National Press club Luncheon with ólafur Grímsson. Iceland’s President ólafur Grímsson will address the global race for resources in the Arctic. The National Press Club.

- Haftendorn, H. (2013). The case for Arctic governance. The Arctic Puzzle. University of Iceland: Institute of international Affairs. The Centre for Arctic Policy Studies.

- Haggard, S., & Simmons, B. A. (1987). Theories of international regimes. International Organization, 41(3), 491–517. https://doi.org/110.1017/S0020818300027569

- Henderson, E. F. (2015). Academic conferences: Representative and resistant sites for higher education research. Higher Education Research and Development, 34(5), 914–925. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1011093

- Hickson, M. (2006). Raising the question Nr. 4 Why Bother attending conferences? Communication Education, 55(4), 464–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520600917632

- Hønneland, G., & Østerud, Ø. (2014). Geopolitics and international governance in the Arctic. Arctic Review on law and Politics, 5(2), 156–176. https://arcticreview.no/index.php/arctic/article/view/1044

- Hufty, M. (2011). Investigating policy processes: The governance Analytical framework (GAF). In U. Wiesmann, & H. Hurni (Eds.), Research for sustainable development: Foundations, Experiences, and perspectives (Vol. 6) (pp. 403–424). Geographica Bernensia.

- Humrich, C. (2013, August). Fragmented international governance of Arctic Offshore Oil: Governance challenges and institutional Improvement. Global Environmental Politics, 13(3), 79–99. https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00184

- Ingimundarson, V. (2014). Managing a contested region: The Arctic Council and the politics of Arctic governance. The Polar Journal, 4(1), 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2014.913918

- Ingimundarson, V. (2015). Framing the national interest: The political uses of the Arctic in Iceland’s foreign and national policies. The Polar Journal, 5(1), 82–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2015.1025492

- Johannsdottir, L., & Cook, D. (2017). Discourse analysis of the 2013-2016 Arctic Circle Assembly programmes. Polar Record, 53(270), 276–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010836716652431 doi: 10.1017/S0032247417000109

- Keil, K., & Knecht, S. (2017). Introduction: The Arctic as a Globally Embedded space. In K. Keil & S. Knecht (Eds.), Governing Arctic change. Global perspectives (pp. 1–18). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Keohane, R. O., & Nye, J. S. (2012 [1977]). Power and interdependence (4th ed.). Little Brown.

- Knecht, S. (2016). The politics of Arctic international cooperation: Introducing a dataset on stakeholder participation in Arctic council meetings, 1998-2015. Cooperation and Conflict, 52(2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010836716652431

- Lackenbauer, P. W. (2014). Canada and the Asian observers to the Arctic Council: Anxiety and opportunity. Asia Policy, 18(1), 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1353/asp.2014.0035

- Manicom, J., & Lackenbauer, P. W. (2013). East Asian states, the Arctic Council and international relations in the Arctic. CIGI policy Brief No. 26. Centre for International Governance Innovation.

- Moe, A., & Stokke, O. S. (2019). Asian countries and Arctic shipping: Policies, interests and Footprints on governance. Arctic Review on Law and Politics, 10(0), 24–52. https://doi.org/10.23865/arctic.v10.1374

- Munich Security Roundtable. (2017). A "posterchild" for cooperation? Report from the MSC Arctic security roundtable Reykjavik. https://www.securityconference.de/de/news/article/a-posterchild-for-cooperation-report-from-the-msc-arctic-security-roundtable-reykjavik

- Nord, D. C. (2010). The shape of the table, the shape of the Arctic. International Journal, 65(4), 825–836. https://doi.org/10.1177/002070201006500413

- Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2014). Norway’s Arctic Policy. https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/nordkloden/id2076193

- Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2017). Norway’s Arctic Strategy - between geopolitics and social development. https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/arctic-strategy/id2550081

- Nye, J. S. (2008). Public Diplomacy and soft power. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 616(1), 94–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716207311699

- Østhagen, A. (2014). Ukraine crisis and the Arctic: Penalties or Reconciliation? The Arctic Institute. https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/impact-ukraine-crisis-arctic

- Østhagen, A. (2016). High North, Low politics - Maritime cooperation with Russia in the Arctic. Arctic Review on Law and Politics, 7(1), 83–100. https://doi.org/10.17585/arctic.v7.255

- Peng, J., & Wegge, N. (2015). China’s bilateral diplomacy in the Arctic. Polar Geography, 38(3), 233–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2015.1086445

- Ragin, C. (1992). Introduction: Cases of "what is a case?". In C. Ragin & H. Becker (Eds.), What is a case. Exploring the Foundations of social Inquiry (pp. 1–18). Cambridge University Press.

- Rhodes, R. A. W. (1996). The New governance: Governing without government. Political Studies, 44, 652–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb01747.x

- Rosenau, J. N. (1992). Governance, order and change in world politics. In J. N. Rosenau, E. O. Czempiel, & S. Smith (Eds.), Governance without government: Order and change in world politics (pp. 1–29). Cambridge University Press.https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511521775.003

- Rossi, C. R. (2015). The club within the club: The challenge of a soft law framework in a global Arctic context. The Polar Journal, 5(1), 8–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2015.1025490

- Scottish Government. (2017). Arctic Strategy for Scotland. https://news.gov.scot/news/arctic-strategy-for-scotland

- Scottish Government. (2019). Arctic Connections: Scotland’s Arctic Policy Framework. https://www.gov.scot/publications/arctic-connections-scotlands-arctic-policy-framework

- Solli, P. E., Rowe, E. W., & Lindgren, W. Y. (2013). Coming into the cold: Asia’s Arctic interests. Polar Geography, 36(4), 253–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2013.825345

- Stokke, O. S. (2011). Environmental security in the Arctic: The case for multilevel governance. International Journal, 66(4), 835–848. https://doi.org/10.1177/002070201106600412

- Stokke, O. S. (2014). Asian stakes and Arctic governance. Strategic Analysis, 38(6), 770–783. https://doi.org/10.1080/09700161.2014.952946

- Tømmerbakke, S. G. (2019, October). This is Why Finland and Iceland Want Security Politics in the Arctic Council. High North News. https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/why-finland-and-iceland-want-security-politics-arctic-council

- Wegge, N., & Keil, K. (2018). Between classical and critical geopolitics in a changing Arctic. Polar Geography, 41(2), 87–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2018.1455755

- Young, O. R. (1982). Regime dynamics: The rise and fall of international regimes. International Organization, 36(02), 277–297. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300018956

- Young, O. R. (1997). Global governance: Drawing insights from the environmental experience (O. R. Young, Ed.). MIT Press.

- Young, O. R. (2005). Governing the Arctic: From Cold War theater to mosaic of cooperation. Global Governance, 11(1), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-01101002

- Young, O. R. (2009). The Arctic in play: Governance in a time of Rapid change. The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law, 24(2), 423–442. https://doi.org/10.1163/157180809X421833

- Young, O. R. (2011a). The future of the Arctic: Cauldron of conflict or zone of peace? (review article). International Affairs, 87(1), 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2011.00967.x

- Young, O. R. (2011b). If an Arctic Ocean treaty is not the solution, what is the alternative? Polar Record, 47(243), 327–334. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247410000677

- Young, O. R. (2012a). Arctic politics in an era of global change. Brown Journal of World Affairs, 19(1), 165–178.

- Young, O. R. (2012b). Building an international regime complex for the Arctic: Current status and next steps. The Polar Journal, 2(2), 391–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2012.735047

- Young, O. R. (2014). Navigating the interface. In O. Young, J. D. Kim, & Y. H. Kim (Eds.), The Arctic in world Affairs. A North Pacific dialogue on international cooperation in a changing Arctic (pp. 225–250). Korea Maritime Institute Press.

- Young, O. R. (2019). Is it time for a reset in Arctic governance? Sustainability, 11(4497), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164497