ABSTRACT

The guidelines on heritage management adopted by the 2018 Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting provide the most recent iteration for an Antarctic tourism sector which had, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, been projected to increase further with various risks and potential impacts requiring careful management. In this paper the role of cultural heritage for tourism prior to the COVID-19 pandemic is examined through three empirical perspectives. First, how the Antarctic cultural heritage is represented through the designation of Historic Sites and Monuments and Site Guidelines for Visitors; then how this is presented through tourism operators’ websites; and, finally, how it is experienced by visitors as narrated in open-source social media information. Each dataset suggests that, while cultural heritage is an important component of an increasingly commodified tourist offering, it is only part of an assemblage of elements which combine to create a subliminal and largely intangible Antarctic experience. In particular, a polarization of the heritage experience between cultural and natural does not appear productive. The paper proposes a more nuanced understanding of heritage tourism in Antarctica which accommodates the notion of a hybrid experience that integrates cultural heritage, the history and stories this heritage represents, and the natural environmental setting.

Introduction

Cool! Wow! Beautiful! Awesome! / Like going back in time. / Amazing! Historic! Finally / I am truly blessed.

Visiting Mr. Shackleton, Manhire, Citation2004, p. 298, verse 1

Visitors may consider close experience with expeditioners’ huts from the early twentieth century, or similar objects that are emblematic of dominant historical narratives, as an important part of the tourist experience which, in turn, could propel the development of tourism attractions in Antarctica (in the sense of Leiper, Citation1990; MacCannell, Citation1976) focused on the cultural heritage. For a rapidly expanding tourism sector, the issue becomes more complicated when considering that several sites around the Antarctic Peninsula that are originally embedded in the Antarctic politics of presence are increasingly developing their tourism functions and receive growing numbers of visitors (notably Port Lockroy, but to a lesser degree also Gabriel González Videla, Esperanza or even Great Wall bases). Alongside increasing tourism numbers to Antarctica and closer attention to tourism management and regulation, a shift in the recognition and management of cultural heritage in the Antarctic has occurred (Davis, Citation1995; Hughes, Citation1994; Powell et al., Citation2008, Citation2012, Citation2016). At a political level, new guidelines on heritage management have been adopted (ATCM Citation2018, Citation2019f, Citation2019g, Citation2019h), and at a scholarly level, there is a growing engagement with the various discourses on cultural heritage, including its intersection with tourism (Barr, Citation2018; Roura, Citation2009, Citation2011, Citation2012, Citation2017; Senatore, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Summerson & Tin, Citation2018).

Cultural heritage is a social construct influenced by the perceptions and values of those involved, which include those regulating tourism, those operating tourism and the tourists themselves. Interaction with, and the designation of, cultural heritage is regulated (a) formally, by Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings (ATCMs) through the adoption of various regulatory instruments that form part of the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS), and (b) de facto, by the tourism industry body, the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO) through the management of visits and visitors. Additional in situ management of cultural heritage in Antarctica is undertaken by individual National Antarctic Programmes and organizations such as the Antarctic Heritage Trust.

In this paper, we examine the role of cultural heritage for tourism in Antarctica. To do so, we look first at the constructs placed around heritage within the Antarctic governance regime, which provide a framework for how humans can engage with Antarctic heritage. Second, we examine how heritage experiences are being facilitated through tourism and to what extent heritage constructs are being accommodated within the tourism industry. Third, we analyse how tourists themselves perceive and respond to Antarctic heritage. We ask what role does cultural heritage play in Antarctic tourism and what kind of narratives are engaged in heritage construction through the discursive practices of these three main group of actors.

During the process of undertaking the research described (2019–2020), the COVID-19 pandemic has made a profound impact globally including on Antarctica. The medium and long-term implications of this in general, and specifically on Antarctic tourism, are very unclear and are likely to remain so for some time (Frame & Hemmings, Citation2020). The paper was written on the premise of a projected expansion of Antarctic tourism though the authors anticipate that this will change considerably. Although the data was collected before tourism activities in Antarctica were suspended, the paper seeks to accommodate the pandemic and the conclusions reached are considered appropriate and feasible based on the data available at the time of writing. Given that the external context is shifting markedly due to the ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic, our findings are likely to be part of a swiftly shifting Antarctic tourism market and also illustrative of tourism modus operandi in recent decades.

Methods

The heritage/tourism intersection is explored through three distinct but inter-connected perspectives and datasets. While each could be considered in and of itself, we view all of them as parts of the wider discourse around tourism and cultural heritage in Antarctica. Our chosen methodological approach is critical discourse analysis which argues that (non-linguistic) social practice and linguistic practice constitute one another and focus on investigating how societal power relations are established and reinforced through language use (Fairclough, Citation1995). Critical discourse analysis is fairly well established within heritage studies as a method to understand how certain powerful discourses constitute heritage and influence practice, but also to reveal competing interpretations of heritage indicative of power hierarchies or value differences among stakeholders (Smith, Citation2006; Waterton et al., Citation2006). To reduce possible bias, we have used a mix of open-access data which is assumed to be representative though, inevitably, not exhaustive of the different stakeholder categories in Antarctic tourism. Our approach adopts a critical perspective in the broadest sense of the post-positivist traditions (Prasad, Citation2017). As such context is central to the data, and we have attempted to counter any bias through internal dialogue. For example, since close to 60% of tourists come from English-speaking countries (IAATO a, Citationn.d.). We have privileged English language datasets, but acknowledge that results could be different if we undertook similar work in, say, Mandarin or Spanish. We are aware of the rich scholarship carried out currently on online ethnography and user-generated content (UGC) such as Facebook, but we will not engage in the methodological challenges of online ethnography in detail, particularly as this field is also rapidly shifting due to COVID-19-induced digitalization.

We explore the intersections between tourism and cultural heritage through a desk-based study that drew on the following datasets: (1) Managing heritage: The lists of Historic Sites and Monuments (HSMs) and the Site Guidelines for Visitors (SGVs) as published by the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat; (2) Operating tourism: Websites and secondary material from IAATO tourism operators; and (3) Perceiving heritage: open-source UGC from Trip Advisor postings, visitor books of Antarctic huts, and geocaching records.

We then proceeded to identify key themes from the datasets. A recurrent thematic division of Antarctic heritage (e.g. Kirby et al., Citation2001) differentiates between: the ‘heroic’ era of Antarctic exploration and exploitation (especially the associated physical structures); the romantic ‘other’ of a vast, unpopulated, extreme environment; and ATS’ goals of peace, science and environmental protection. However, for our data, de la Barre’s (Citation2013) classification relating to the relationship between the concept of identity and sustainable tourism in remote areas proved to be more productive. de la Barre (Citation2013) describes three main narratives which we adopt for Antarctica, namely: (1) Masculinist Narratives which describe the Antarctic as an idealized space associated with wilderness in opposition to ‘civilized’ urban space and present Antarctica as a place for testing and confirming masculine identities including characteristics of self-sufficiency, individualism and freedom. (2) Narratives of the New Sublime which convey a connection to the existence of an original and authentic self, tied to an idealization of nature and wilderness with roots in the Romantic Movement. (3) Narratives of Loss which reveal relationships to disappearing landscapes, landscapes that are perceived to be endangered and landscapes that have already been destroyed.

These categories are more firmly anchored in the tourists’ sense of identity than the common chronological categories of heritage and allow us to identity repetitive discursive elements across the chronological divisions. In addition, we specifically noted whether texts referred to heritage with origins during the Heroic Age, including the earlier maritime era (Senatore, Citation2019a, Citation2019b), or the scientific era, which is taken here as the period from 1945 through the International Geophysical Year (IGY) in 1957/58 and to 2020.

Tourism in Antarctica

In 2020, the majority of Antarctic tour operators are members of IAATO, with 45 full member operators which have decision-making rights at IAATO meetings, five provisional member operators, who are awaiting confirmation as full member operators once they fulfil all requirements as full members, and a further 58 Associates, which include agencies and companies booking onto IAATO member programs or non-profit organizations, such as the UK Antarctic Heritage Trust. IAATO and its members work within the ATS’s regulatory framework, and IAATO representatives attend the ATCM each year as invited Experts and also as members of some national delegations. IAATO has been, and continues to be, instrumental in the development of Site Guidelines for Visitors (SGVs) for frequently visited landing sites in the Antarctic and requires its member operators to adhere to these guidelines, even though they are not binding in a legal sense. The Site Guidelines were developed in 2005 and used as a management tool (ATCM, Citation2019g). The primary function of the site guidelines is to provide specific instructions on the conduct of activities at the most frequently visited Antarctic sites. SGVs’ management of cultural heritage is secondary to the obligation that HSMs shall not be damaged, removed or destroyed. IAATO’s annual Overview of Antarctic Tourism documents the scale and range of commercial activities, including the following highlights (ATCM, Citation2019c) for the 2018–19 season: 56 vessels operated or owned by IAATO members visited the Antarctic, with 35 of these vessels offering traditional seaborne expedition tourism with landings in the Antarctic Peninsula region. These 35 vessels carried over 44,000 passengers and made over 300 individual voyages to the Antarctic that season.

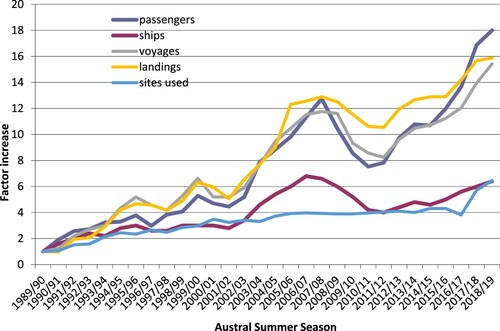

Overall tourism numbers to the Antarctic increased by over 50% in the five years from 2014–15 to 2018–19, largely through expedition-style cruise tourism with 56,168 visitors traveling with IAATO member operators in the 2018–19 season, an increase of 8.6% compared to the previous season ( and ) (ATCM, Citation2019d). This figure was expected to increase by another 40% in the next few years (Cruise Industry News, Citation2018; Read, Citation2018), disregarding the anticipated impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which cannot currently be meaningfully predicted. The number of vessels operating around Antarctica was estimated to rise to around 60 vessels by 2021/22, with capacity for a further 5000 berths (ATCM, Citation2019a). These new ships would have extended operational capacity of up to 40 days with greater ice-strengthening and the use of hybrid propulsion systems. Of these at least four would have on-board helicopters and two would have seven-person submarines (Cruise Critic, Citation2020), which suggests an anticipated growth in seaborne adventure tourism, a small sub-sector that has grown by 167% between 2014 and 2018 (IAATO b, Citationn.d.) and relates discursively to the masculinist explorer narrative.

Figure 1. Factor Change in Traditional Ship-borne Expedition Tourism (involving landings) in the Antarctic Peninsula 1989–2019 (ATCM, Citation2019d).

Table 1. IAATO’s Top Twenty Most-Visited Sites during the 2018–19 Season (including yacht visits) and Their Relationship to HSMs (Based on ATCM, Citation2019d).

Within this market, over 98% of the tourism services offered were variations of ship-based cruises to the Antarctic Peninsula. Tourism operators active in this market segment differentiate themselves from others through a wide range of additional sea-borne or on-shore activities (ATCM, Citation2019e). Operators place different emphasis on different characteristics of the itineraries and vessels they offer in terms of comfort, duration and access (e.g. fly-cruise [such as Antarctica 21 (Citation2020), Quark Expeditions (Citation2020) and others], cruise with landings, cruise with no landings). There is also a particular emphasis on different activities (e.g. photography, kayaking, camping, ski-touring, polar plunge, etc.) and access to specialist lectures (e.g. climate scientists (Wild Earth Travel, Citation2020a), wildlife biologists, expeditioners (White Desert, Citation2020)). Some cruises offer access to less-visited locations (e.g. helicopter travel to the McMurdo Dry Valleys, an ‘expedition’ cruise from Argentina to the Antarctic Peninsula and onwards to the Ross Sea (Oceanwide Expeditions, Citation2020)); or trips to the South Pole (Abercrombie and Kent, Citation2020a). Mainly, however, these expeditions tend not to feature cultural heritage as a lead attraction although it is present in almost all trips to some extent, as expressed in evocative trip descriptions such as the following one: ‘pause for a moment at [Shackleton’s] graveside’ (Wild Earth Travel, Citation2020b).

Heritage in Antarctica

Heritage is a multifaceted term that encompasses different perspectives on the past and the uses and values assigned to the material remains of past activities. As a concept, it is extremely ambiguous and can refer to anything from a book or a building to traditional practice; yet it is not a thing but a relation, a formally staged or communally valued encounter with the physical traces of the past in the present (Harrison, Citation2013; Smith, Citation2006). However, although recent years have seen growing collaboration between the ATS and international heritage institutions, particularly the International Polar Heritage Committee of the International Council on Monuments and Sites, heritage has not been the concept of choice in Antarctic governance. Instead the ATS has spoken of HSMs in a rather non-constructivist terms, whereas the term heritage formally appears in ATS documents as late as in 2018.

Particularly important for Antarctica is to revisit the distinction between cultural and natural heritage as these often conflate in expressions of tourists’ experiences (though not necessarily in the management of the region). In particular, Powell et al. (Citation2016) note that:

While it is accepted that all heritage is a human construction and that the natural/cultural heritage dichotomy employed in many heritage designations and descriptions – particularly at the global level – has largely been discarded, … . The cultural heritage narrative in an extreme and climate-sensitive natural landscape [is] a means of using human heritage narratives as a means of discussing broader environmental issues (p.72).

Managing heritage

Given that Antarctica is essentially an uninhabited continent onto which the ATS projects a construct of governance, it is important to estimate the extent to which human society has impacted the continent, in essence providing the basis for what has later become recognized as cultural heritage, and what processes have been established to manage that heritage, including the approach taken to managing interactions between said heritage and tourism.

Human presence in Antarctica is no more than 200 years old, yet it is surprisingly extensive. Leihy et al. (Citation2020) assembled an extensive record of ground-based human activity across Antarctica and its offshore islands covering the period 1819–2018 and estimated about 2.7 million activity localities. They defined, in a very reductionist manner, an Antarctic wilderness area as being greater than 10,000 km2 and having had no ground-based human activity. From this they concluded that wilderness only constitutes about 31.9% of the continent’s surface area, a figure which may be surprising to many. Human presence is managed principally by the respective national Antarctic programs within whose operational realm human activity occurs. Brooks et al. (Citation2019) estimated the footprint of buildings in Antarctica to be around 390,000 m2, with an additional disturbance footprint of more than 5,200,000 m2 with cultural heritage sites by and large included in this inventory. However, this extensive anthropogenic presence is not necessarily understood by tourists (or shared by other actors) who see Antarctica as ‘wilderness’ and the definition of what constitutes wilderness remains a contested concept.

We turn next to the protected area system which has been in place since the early 1960s, and is regulated by Antarctic Treaty Parties through the 1991 Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty’s (the Protocol) Annex V on area protection and management (1998/2002). Antarctic Specially Protected Areas (ASPAs) can be created to afford special protection to areas of outstanding environmental, scientific, historic, aesthetic or wilderness values, any combination of those values, or ongoing or planned scientific research. Antarctic Specially Managed Areas (ASMAs) are intended ‘to assist in the planning and co-ordination of activities, avoid possible conflicts, improve cooperation between Parties or minimise environmental impacts’ (Annex V Art. 4(1)). Sites or monuments in Antarctica that are of recognized historic value can be designated as HSMs. In turn, tourism and other visitor activities at some sites that are frequently visited, including at HSM sites, are managed by the Site Guidelines, which were originally conceived by IAATO and then adopted by the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Parties as a hortatory regulatory mechanism in 2005. The guidelines apply to all visitors, whether they are tourists or National Antarctic Programme participants engaging in recreational activities.

As argued by Barr (Citation2018), Lindström et al. (Citation2021) and Roura (Citation2017), the institutionalization of Antarctic heritage processes started with preparations for the first ATCM in 1961. Following discussions in the intervening years, at ATCM VII in 1972, the Parties recommended a list of Historic Monuments Identified and Described by Proposing Government or Governments be approved. The listing implied a degree of protection to those material remains, including with respect to incipient tourism, but provided little in terms of practical management. Since then until 1985, the list of HSMs expanded from 43 to 52. At ATCM XIV in 1987 and ATCM XV 1989, the approach to regulating and managing Antarctic HSMs was re-evaluated, and, with the adoption of the Protocol, formal heritage-creation processes became part of the environmental governance structure, with specific criteria for their designation and management being agreed on in 1995. Guidelines were produced that explicitly included language on cultural significance and further revised for ATCM XLI (Citation2018). with a list of 89 HSMs. There are 89 historic sites listed and these are numbered 1–94 of which three HSMs have been delisted and two have been subsumed into a different HSM encompassing several historic features and 42 SGVs supported by revised assessment and review checklists (ATCM, Citation2019f, Citation2019g, Citation2019h). Following a de facto moratorium on the adoption of new HSMs from 2014, the 2018 guidelines formalize the concept of heritage in Antarctica as a category inclusive of, but broader than, HSMs. This generic denomination opens the possibility of managing heritage off-site rather than through HSM designation which, in most instances, implies on-site conservation and management. Implicitly this introduces greater pressure for Parties to clean up sites of past activity in Antarctica (Roura, Citation2017; pers. obs. at ATCMs 2014–2018).

Revisiting archival records relating to heritage in Antarctica from 1959 to the late 1980s in a number of AT member states (Lindström et al., Citation2021), we observed that discussion around HSMs and the general principles of heritage management does not receive significant attention in ATCMs and their reports, or in the various correspondences leading up to the meetings to which we had access. Our interpretation of this is that heritage, at least in the early years of the ATS, has not been a priority topic in the context of formal meetings. Rather, there seemed to be an accommodation of interests where all Parties had an opportunity to list historic remains of value to them as HSMs, and this choice was, by and large, accepted by other Parties. This is consistent with observations at ATCMs where HSMs were discussed (Roura, Citation2017 cited in Dodds et al., Citation2017).

ATS documents establish an authorised heritage discourse (Smith, Citation2006) around Antarctic heritage, defining what is included in the official heritage of the ATS. While the historic development of the heritage process is discussed by Barr (Citation2018) and Lindström et al. (Citation2021), the emphasis here is on the contemporary list of HSMs. SGVs apply to several of these sites (ATCM, Citation2019f, Citation2019g, Citation2019h). Most HSMs fall quite evenly across heritage originating in the Heroic Age and the scientific era. Using the evaluation criteria outlined in Resolution 3 (2009) to assess whether an object or site has a ‘recognised historic value’ (namely, event, person, feat, activity, construction, study, or symbolic for many), all of the current HSMs fit broadly at least one of these official value criteria, with most loosely complying with two or more criteria. A more detailed assessment of the criteria met by each HSM is relatively subjective, and one interpretation is given in which suggests, perhaps not too surprisingly, a shift from the specificity of an event, person or feat during the Heroic Age towards a more even attribution of criteria in the scientific era. The geographical distribution of the HSMs throughout Antarctica is discussed in detail elsewhere (Brooks et al., Citation2019; Lintott, Citation2018; Roura, Citation2017). Each HSM has one or more proponent country, with almost three quarters of the proposing parties being claimant states (United Kingdom, New Zealand, Argentina, Chile, Norway, Australia and France in decreasing order).

Table 2. Distribution of HSMs against the evaluation criteria (ATCM Resolution 3, 2019) and allocated to one of two eras. Some sites cover both eras.

Of the HSMs, a much smaller proportion feature in SGVs as the latter are not an obligatory means of managing HSMs. Site Guidelines effectively complement existing regulations, such as ASPAs or ASMAs, or are developed because a particular HSM is used frequently by Antarctic tour operators. In 2019, of the 42 SGVs published, the majority are on the Antarctic Peninsula (25) and its offshore islands (13), with only four in the Ross Sea region and a few others elsewhere on the continent. In the list of SGVs, 15 include HSMs. In some cases, HSMs are also included in ASPAs (e.g. HSM 15 in ASPA 157; HSM 76 in ASMA 4; and HSM 77 in ASPA 162 and ASMA 3), and in these instances a degree of protection is extended to discrete areas. This double protection is testifies to the hybridization of Antarctic heritage where cultural and natural elements fuse.

When viewing the evaluation criteria explicitly identified in Resolution 3 (2009) (namely, event, person, feat, activity, construction, study, or symbolic for many) for HSMs through de la Barre’s (Citation2013) classification they can be seen as constructs that are primarily ‘masculinist’ and, to a much lesser extent, narratives of loss. There is very little that can be attributed to the subliminal though it could be argued that, under the ATS, the ‘subliminal’ as an attribute is being considered within the protected area system.

Providing Antarctic tourism and heritage

While heritage is, of course, present throughout the continent, it is only really on the Antarctic Peninsula and its offshore islands that it intersects with the bulk of contemporary tourism by commercial operators. A second cluster of heritage sites used for tourism purposes is located in the Ross Sea region where tourism is much more limited, but where the historic sites themselves are among the most representative of Heroic Age narratives. Heritage sites in these regions of Antarctica are relatively accessible, from a logistical point of view, and provide the stories and the sights that enable the development of tourism attractions (as defined by Leiper (Citation1990), MacCannell (Citation1976) and Roura (Citation2011)). Accordingly, Antarctic heritage as constructed through tourism does not include all HSMs nor is it limited to this formal nomenclature.

As already indicated above, Antarctic tourism is a dynamic activity, with numbers of commercial operators increasing rapidly from the early 1990s up to the 2019–20 season amid an increase in luxury tourism globally (Amelung & Lamers, Citation2006; Bender et al., Citation2016; Liggett et al., Citation2011, Citation2017; Liggett & Stewart, Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Schillat et al., Citation2016; Stewart & Liggett, Citation2018; Student et al., Citation2016). Antarctic tourism operations range from visits to the Antarctic on large non-landing cruise ships (carrying in excess of 500 passengers) through expedition cruises carrying up to 500 tourists and involving landings in the Antarctic, to yacht and land-based adventure tourism, which includes small parties making expedition-style visits to sites such as the South Pole or the Vinson Massif. The latter type of tourism represents part of the increasing commodification of the Earth’s extremes (e.g. Elmes & Frame, Citation2008). This includes ‘conquering’ the Seven Summits (the seven highest summits on the seven continents) (Bass et al., Citation1986), the Three Poles Challenge (Everest, North Pole, South Pole) (Huettmann, Citation2012) and the Explorers’ Grand Slam (Citation2020) (the Seven Summits and the North and South Poles).

In terms of an Antarctic visitor’s experience, a survey undertaken by Powell et al. (Citation2012) suggests that Antarctic tourism offers a complex experience that evokes a suite of psychological, emotional, and spiritual responses. Powell et al. (Citation2012) suggest that the ‘Antarctic tourism experience’ was relatively successful at ‘enhancing public awareness and concern for the conservation of the Antarctic environment’ (p. 154). However, Powell et al. (Citation2012) did not distinguish between experiences in relation to the Antarctic environment (‘nature’) and interactions with Antarctic heritage (‘culture’), which makes it difficult to extrapolate any of their findings and applying them to Antarctic cultural heritage. In fact, a clear distinction between human heritage and environment in the Antarctic is rare in studies exploring tourists’ interactions with, and experiences in, the Antarctic. This suggests that Antarctic heritage is more a hybrid phenomenon where historical remains and natural environment are particularly tightly linked, but makes it difficult to evaluate how large a part the cultural element plays in its reception.

Within cultural heritage scholarship, the discussion is largely limited to tourism operations in the Antarctic Peninsula, which receives the majority of tourism visits (over 98% of tourists visited this region in the 2018–19 season (ATCM, Citation2019b, Citation2019c)). To gain some insight into how cultural heritage was marketed to prospective Antarctic tourists by IAATO operators, we reviewed the websites of IAATO’s 45 full member operators (in August 2019 and April 2020) to examine tourism operations for a sense of their inclusion of cultural heritage. Of these, about 30% had, ostensibly, little apparent focus on Antarctic cultural heritage. Most of the remaining 70% explicitly mentioned opportunities for tourists to engage with Antarctic cultural heritage – mostly through landings at HSM sites. However, the engagement with cultural heritage was almost entirely portrayed as being secondary in importance to interactions with wildlife and the landscapes. Among the tour operators whose websites we analysed, three stood out for their emphasis on cultural heritage. These include two operators offering expeditions to sites in the Antarctic Peninsula and one operator from New Zealand who regularly visits the Ross Sea region and Commonwealth Bay in East Antarctica. Outlines of the respective operators’ expedition descriptions are provided in .

Table 3. Cultural heritage specific tours offered by IAATO operators in 2020.

Referencing the Heroic Age, and to a lesser extent the scientific era, is a distinct component of the offers made by tour operators. These sit alongside the comfort, the excitement (the above itineraries are all distinctly branded as ‘expeditions’, not ‘cruises’ or even ‘journeys’), the wildlife and the landscape as critical components of the overall touristic experiences. They do not, however, appear to have, even in the examples given above where cultural heritage is specifically named, especially heavy weighting. The overall impression from analysing multiple websites and brochures is that cultural heritage is an essential part of the package but not one that dominates the pitch for attention. While the narratives, to use de la Barre’s (Citation2013) classification, are ostensibly masculinist in their reference to the Heroic Age, they appear as much wrapped in the sublime expressed in terms of the ‘environment’, ‘wildlife’ and ‘nature’ as in terms of cultural heritage and, to a much lesser extent, of loss. So, in a sense, the customer is being offered sites and activities that correspond to dominating media representations of Antarctica and, as we will now see, this is largely what appears to be experienced.

While ATS documents determine what is the official heritage in Antarctica, in as much as sites and monuments whose historic value is recognized by Antarctic Treaty Parties, tourist materials are the frame of reference for all Antarctic tourist experience, as travelers would seldom read ATCM documents first-hand. Interestingly, tourist materials do not make particular reference to HSM protection in order to sell the heritage experience, even if it is undoubtedly mentioned during the many lectures given during the ‘expedition’. Possibly, a complicated international legal regime contradicts the ‘masculine explorer in the sublime environment’ discourse that frames the experience. In the same vein, tour operators do not limit themselves to official Antarctic heritage, neither geographically nor in terms of the HSM. The three above-mentioned examples of ‘heritage cruises’ include visits to sub-Antarctic islands and even for those located within the Antarctic Treaty Area most of the early sealing and whaling sites visited do not find mention in the HSM list. There are geopolitical explanations as to why whaling and sealing sites are underrepresented among the HSMs. Sites of early sealing activities represent the first occupation of the Antarctic, resulting in geopolitical sensitivities (Roura, Citation2017, pp. 475–476; and Kati Lindström (unpublished interviews)). Yet, for tourism, they offer a discursive bundle of masculine and sublime in an explorer narrative.

Perceiving cultural heritage

IAATO, in its preliminary estimates for the 2019–20 season, anticipated that 59,367 tourists would have made landings and that there would a further 18,420 cruise-only passengers would have visited Antarctica (ATCM Citation2019c). In addition, 733 tourists were estimated to have participated in Deep-Field expeditions in 2019–20, of which about a third were intent on visiting the South Pole, which is itself a significant site and the location of two HSMs (1, 80). Overall, since 1992, more than half a million tourists have landed in Antarctica on expedition cruises or yacht visits, and more than 150,000 tourists have visited the continent on cruise-only voyages (ATCM, Citation2019c). To understand the collective perceptions of this group of individuals is immensely difficult. We draw initially on the work of Powell et al. (Citation2016) who examined the Antarctic tourism experience, and build on that through UGC on social media from visitors using Trip Advisor, HSM visitor books and geocaching as proxies for their perspectives.

Powell et al. (Citation2016) studied the interplay and interrelationships between the natural and cultural heritage resources on four different Antarctic voyages in 2014. They found that cultural heritage provided a narrative vehicle for broader environmental issues and that tourists tended to see the natural and the cultural environments ‘in a symbiotic, rather than a dichotomous relationship’ (p.71) in a way that is similar to that experienced by scientists (Kirby et al., Citation2001). In particular, they note that ‘Antarctic tourists view nature, history and the values associated with the treaty as interconnected parts of the same heritage story’ (p.83). They argue that an immersive experience of the harsh Antarctic environment provides a sense of ‘empathetic authenticity with the people and events of the past’ and that ‘Antarctica perhaps provides a globally-unique context where the natural/cultural heritage dichotomy is eliminated’ (p.84). In a sense, as noted by Barr, without the harsh polar setting the polar cultural heritage would not be ‘understandable, iconic nor historically valuable witnesses to previous events.’ (Citation2018:, p. 247).

UGC on Trip Advisor

Social-media platforms are a central element of contemporary tourism through the sharing of experiences, images and recommendations as well as important sources for travel information (van der Zee et al., Citation2018). Tourists use social-media platforms to create and share content in order to be inspired and assist in their decision-making (Hudson & Thal, Citation2013; Xiang & Gretzel, Citation2010). UGC can, in turn, be used to inform tourism management (Marine-Roig & Clavé, Citation2015; Roura, Citation2012; Zeng & Gerritsen, Citation2014). Although the representativeness of UGC as a data source of tourist behavior is imperfect – for example, not every tourist creates UGC and those that do create content do so in a selective manner (Hernández et al., Citation2018) – UGC does provide some insight into voluntarily provided information on perceptions of destinations. While the process for turning UGC into knowledge about the destination remains to be a methodological challenge, it offers some initial insight on the tourism experience, including into how tourists perceive cultural heritage in Antarctica and what they consider ‘post-worthy’.

Our review of Trip Advisor posts was restricted to the Antarctic Peninsula. Trip Advisor has country-specific websites, and we, initially, examined www.tripadvisor.co.nz. All posts were in English, and our search was for ‘Antarctic Peninsula – Things to Do’, with the top hits shown in . Posts were read on three occasions over eight months. As of 4 April 2020, 561 reviews of 20 sites had been posted relating to ‘Things to Do’ in the Antarctic Peninsula. Those relating to tourism providers, transport and accommodation or those wrongly attributed to the Antarctic Peninsula were ignored. Posts relating to places and landscapes with no discernible historical remains, most notably the Lemaire Channel with 111 posts, were not considered further. This left 413 posts from November 2014 to February 2020 relating to 7 HSM sites, each averaging a 100 or so words, for closer study (). Trip Advisor automatically translates its contents across jurisdictions, and a quick check on other countries’ sites with the help of VPN revealed that the differences in contents were not significant and country bias was small. However, it should be noted that posts which are voted as ‘useful’ or ‘liked’ do show clear geopolitical dimensions.

Table 4. Trip Adviser postings of Visits to HSMs on the Antarctic Peninsula (at 4 April 2020 from https://www.tripadvisor.co.nz/Attractions-g660183-Activities-Antarctic_Peninsula.html).

Port Lockroy has more than 17,000 visitors per season and an average of two ship visits per day over 110 days, making it Antarctica’s single most-visited site, with the Penguin Post Office at Port Lockroy handling over 70,000 items of mail (BPU, Citation2018). It is one of the few sites purposefully redeveloped as a tourism destination, with easy landings and things to see and buy in an outstanding natural setting. This is undoubtedly a pull factor when compared to other sites. This, not surprisingly, dominates the Trip Advisor posts, with the main base building, Bransfield House, featuring in 103 posts and the generator shed housing the Penguin Post Office being the main focus in an additional 139 posts. Port Lockroy is managed by the UK Antarctic Heritage Trust, a British heritage charity that is also an IAATO Associate Member, as a living museum and as a representative British science base from the 1950s (‘Base A’, HSM 61). The proceeds from the gift shop at Port Lockroy support its operation and that of other British historic sites in Antarctica. The Trip Advisor comments on the Penguin Post Office refer to the post office as a ‘Number 1 Tourist Hotspot’ and ‘Philatelic dream’, and assertions that this is a must-visit site, even if ‘just for the bragging rights’ support its popularity as a ‘highlight’, which includes interactions with the staff and the ability to stamp a passport – a minor but not insignificant political act of legitimizing national presence (Roura, Citation2011). The only downside, for some visitors, appears to be the lengthy wait time to receive the mail. It should also be noted that many Antarctic stations, operated by claimant and non-claimant nations alike, stamp the passport of tourists and other visitors as a souvenir of their visit; few stations, however, are operated primarily to receive tourism visits, as Port Lockroy.

The Bransfield House posts are almost unanimous in their praise, even excluding the excessive use of exclamation marks. Exemplary quotes refer to Bransfield House as a ‘history buffs [sic] heaven’, an ‘impressive piece of history!’ and opportunities to experience ‘science and shopping in Antarctica.’ These posts and quotes are indicative of Port Lockroy’s success as an immersive experience where attention to detail in terms of the exhibits indicates a high level of engagement, perhaps best emphasized by this entry:

One of the most poignant exhibits for me was the oral history voice recordings of reminiscences from the men, talking about how they were recruited, how they lived, what their experiences in the program were like. It was a privilege to listen to, standing in the site that they were discussing.

The remaining 41% of posts on other sites also expressed appreciation of heritage values within the obvious constraints of social-media postings. This was especially the case in relation to Deception Island (HSM 71), as indicated by an outpouring of superlatives regarding the scenery and general experience as is the linguistic style of UGC (‘stunning’, ‘awesome’, ‘wow’, ‘cute’, etc.).

Visitor books at HSMs

Bill Manhire’s 2001 poem ‘Visiting Mr Shackleton’ (Manhire, Citation2004), which opens this article, used comments from the visitor books in Shackleton’s Discovery Hut at Cape Royds which echo the language of the UGC, albeit in long-hand. While rushed and written in cold conditions, these offer a glimpse of the immediate response of visitors to a historic site. We asked the Archives Manager at the British Antarctic Survey to review Port Lockroy visitor books (November 2015 to March 2019), and his summary is provided, unedited, herewith:

The comments are all positive, but also short. The vast majority (c.70%) are one-word comments (“awesome”, “wonderful”, “incredible”, “fabulous”, “beautiful”), although this brevity may have as much to do with the space available to write in the book, as well as the fast-paced nature of the visits ashore. It is also unclear in the majority of comments if they relate to Port Lockroy, the immediate locality, or Antarctica in general. The awe seems to largely stem from stepping foot on the continent.

A number of comments speak of the privilege of visiting (again, this could be as much to do with the environment as the heritage). Where the heritage is mentioned (c.20%), comments tend to be longer. A representative sample reads: “Great preservation – keep up the good work”; “Great museum”; “We loved this step back in time”; “A truly magical place that captures such a special moment of history”; “Thank you for preserving this treasure”; “A charming and fascinating place of important memories”; “What a great museum. Really makes you appreciate the conditions of the time and love the penguins. Thank you for maintaining this heritage site”.

I’ve also compared them with the visitors books for Damoy (4 vols. Jan 2013 to Dec 2017) and Wordie (1 vol. Jan 2013 to Jan 2014), with very similar findings.

… .I’m surprised that, given the uniqueness of the experience, people don’t write more, or more varied responses are recorded.

“When we look at Antarctica, from the deck of a ship, or in a make-believe tableau, and fix it in our gaze, what we see is a figment of the imagination. The sight we encounter is a sight already seen, image upon image fixed in the shadow of our dreaming by the medium of photography itself. First seen and drawn by artists, and cartographers (who because mirages were frequent, mapped whole coastlines that did not exist) then photographed by the great heroic-age photographers Herbert Ponting and Frank Hurley, the Antarctica of our dreams is a visual domain cast in a pattern already set – as a picturesque wilderness (but we are there) and as a photographer’s paradise (ice cliffs, and penguins floating on bergs). Photography confirms a ‘having been there’ that is desirable, touchable, and ultimately purchasable. It becomes the pre-text for travel and loads a geographic imaginary that renders the traveller blind” (Noble, Citation2011 p. 126)

Geocaches

A further, smaller, dataset comes from geocaching, a recreational activity in which a GPS-enabled device is used to find ‘caches’ (physical or virtual). It is a very distinctive recreational pursuit by tourists and other Antarctic visitors alike. Antarctica has 49 currently active geocaches of which 18 are on the Antarctic Peninsula and the rest distributed, mainly, in and around various bases (Frame et al., Citation2018). It should also be noted that some geocaches get deactivated if the physical cache goes missing or if it is no longer maintained and that some older caches are in breach of the HSM guidelines though this practice no longer appears to take place. In total, about half of the ‘caches’ have, as can be expected from the Trip Advisor analysis, some connection to the scientific era or Heroic Age though only a few make direct reference to the heritage component, such as the plaque to the American nuclear power station PM-3A (GC38PWN – HSM 85) and ‘Base Y’ on Horseshoe Island (GC5QB7V – HSM 63). Most formal ‘finds’ have been, unsurprisingly, at Base A – Port Lockroy (GC4TM62 – HSM 61), with 216 logs (including 26 in the 2019–20 season) of which the bulk suggest a pre-occupation with t-shirts and postcards (Geocaching, Citation2020). A read of the logs for the heritage-related caches suggests that landscape and bragging rights are more important than engagement with heritage, which, as such, connects with none of de la Barre’s (Citation2013) narratives unless bragging rights are interpreted in terms of the masculine explorer narrative.

In summary, our read of the various insights into the overall touristic perception suggests that cruise-ship operators provide what they promise, and there is an important cultural heritage component to the generalized tourist experience. Peeling away the transactional (delivery of postcards, etc.) and the social-media fashion for superlatives, does, however, leave text that concentrates on the subliminal responses (wonder, awe, other-worldliness, etc.) of the natural experience and much less on the achievements which led to the HSM status, or to the vulnerability and potential loss through either time (in terms of historic value) or global change processes. This is consistent with the overall findings of Powell et al. (Citation2016) and particularly that the natural/cultural heritage dichotomy is not a significant construct in the Antarctic context from a tourism perspective.

Discussion

ATS instruments such as HSMs establish the official heritage, but they are more of a product of political compromises at ATCMs rather than a summary of practiced heritage values. HSMs are originally an instrument of legitimizing presence through heritage management in a geopolitically loaded period (Lindström et al., Citation2021) and have even now bigger importance for in-system accommodation and management than for tourist experience. HSM designation lacks the trademark value of World Heritage, and it is often not mentioned in publicity or UGC. Antarctica is a mediated continent: most people have ‘met’ it in a variety of mediated forms long before they get there. Narrative frames through which Antarctica is perceived are born outside of the ATS in the realm of popular culture, media and the tourism industry – all of which draw heavily on the sublime of the ‘virgin’ natural environment and heroic explorations (e.g. Leane, Citation2012; Manhire, Citation2004; Nielsen, Citation2017; Wainschenker & Leane, Citation2019).

Tourism experiences give an audience to the remains of some historical (past) Antarctic activities, whether or not these remains are listed as HSMs. For the duration of a usually brief visit, tourists have the opportunity to experience for themselves the sights and setting of historical (past) events. The tourism experience is ephemeral, and its attractiveness is influenced not only by existing material remains but also by the narratives or markers in which these are presented to tourists (MacCannell, Citation1976). The tourism experience of Antarctic heritage is not universal – different individuals may respond differently to particular sites, depending, for instance, on their nationality. Furthermore, all past-activity sites have a history, but the story told may vary from one group to the next as different guides may give their own interpretation of how some remains fit in the historical record (Roura, Citation2009). HSMs respond to a certain typology of sites, according to ATS criteria and instruments, but these are not necessarily the primary reason for visiting those sites. This is to say that Antarctic tourism experiences are often instrumental and transactional, and influenced by factors other than historic significance or the values attributed to the sites.

In several quotes we noted that the ‘awe’ stems from stepping onto the continent, indicating the importance of an intangible element in the heritage experience, well beyond the not-so-spectacular physical artefacts. The fact that the heritage experience is influenced by mediated images does not reduce its authenticity for the tourist. Bodily immersion in the polar environment is part of the heritage value in this context, one that links directly to the historical values of the Heroic Age, and also the early scientific age. More than 70,000 tourists visiting Antarctica per year can hardly be considered a community in the sense of UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage Convention, yet we can perhaps join Russell (Citation2010) in claiming that all heritage is essentially intangible: physical structures are just symptoms of agencies, perceptions, values, practices and mediations. To recognize the hybridity of Antarctic nature-cultural heritage, as well as the authenticity of sublime experience, could counter the risk of shallow commodification of the Antarctic tourism experience. It could potentially lead to a more nuanced understanding of the role of heritage in Antarctic tourism and what guidelines might be needed to navigate effectively between formal monitoring requirements and the expectations of tourism operators and their clientele. It could ease the tension between official Antarctic Heritage embodied in small numbers of physical/cultural elements (huts, cairns, memorials, etc.) and the vast subliminal experience, especially when, as noted earlier, much of the continent shows some evidence of past activities or at least has been previously visited (Leihy et al., Citation2020). For tourism experiences, historic sites are set in a natural setting that gives them context and meaning and enables tourists to have a glimpse of past Antarctic events. Conversely, sites visited for their natural values, at least in the Antarctic Peninsula, often contain material remains from past activities, whether or not these are included in the official list of HSMs. Perhaps the nature-culture divide is indeed redundant for tourism in the Antarctic context.

However, some researchers perpetuate this divide between cultural and natural. For example, although Barr acknowledges the interrelation between historic sites and monuments and their natural setting, she also notes that, ‘ … whereas natural heritage may be able to renew itself – worn-down landscapes may recover given time, flora and fauna populations can regenerate – cultural heritage is a non-renewable resource’ (Citation2018:, p. 244). Not only does this fail to recognize the complexity and fragility of ecosystems, it also neglects to acknowledge the subliminal experience which arises from engagement with both. While natural heritage may regenerate itself to a degree, this results in something new, not what was there before. The same applies to cultural heritage, e.g. if a historical hut burns to the ground, it is obviously gone, but the site remains and possibly a memorial or a reconstruction will be built, or perhaps just the empty site will be visited to experience the place. In the meantime, more material culture is being created that is potentially future heritage. By polarizing the divide and ignoring the fragility of environmental landscapes and the impact of, inter alia, climate change potentially weakens the case for carefully managed heritage resources and experiences. It is important to stress, however, that this is not relegating heritage to be less important than other aspects of human interaction with Antarctica. We advocate for the notion that heritage, like the ‘environment’, like ‘nature’, like ‘exploration’, is part of a social construct that is constantly being re-contextualised and re-imagined.

Concluding comments

At the time of this research, the future of cultural heritage tourism in Antarctica was unclear at multiple levels. On the one hand, new heritage guidelines adopted by the ATCM in 2018 formalized the concept of heritage in connection to HSM management and introduced the idea that some of the Antarctic heritage may merit protection, but not necessarily on site and not necessarily through listing as HSM (in other words, any Antarctic Treaty Party can take care of its own heritage back in the country of origin, unless it merits designation as HSM). On the other hand, by the end of the 2019–20 season, there was an obvious tension between regulation and monitoring by Antarctic Treaty Parties (e.g. through ATCMs) and increasing tourism pressure compounded by increasing global mobilities, particularly the increase in Antarctic tourism from new markets, notably China. However, the effective cancelation of the 2020–21 tourism season due to the COVID-19 pandemic suggests that global tourism could now be facing quite different pressures, especially considering the significant economic changes that are likely to ensue.

Given that the tourism industry took a decade to recover from the Global Financial Crisis (Liggett et al., Citation2017), the recovery from COVID-19 could be of a similar duration (Frame & Hemmings, Citation2020). So, looking beyond 2030, global tourism may well have to accommodate changes in travel patterns arising from adaptation processes to pandemics and in response to the global climate crisis, even if only relevant to those countries who are signatories to the Paris Accord. Furthermore, given the pandemic has included incidents with large cruise ships, and bases remain closed to non-essential visitors, there may well be a sustained shift in Antarctic tourism. However, all of this is beyond the scope of the current paper and may not be resolved for some time.

Based, however, on our examination of the three aspects of cultural heritage in the Antarctic tourist experience (management, production and experience), we conclude that, while cultural heritage forms an important part of Antarctic tourism, it is not necessarily distinct from a broader, more subliminal, perspective. In other words, cultural heritage, along with wildlife and landscape, provides an assemblage of complementary elements that define the touristic Antarctic experience, in itself pre-mediated by the tourism industry, media and pre-existing UGC. Obviously, the elements will have varying importance within the tourist population but not, it appears, sufficiently for operators to frequently market differentiated cultural heritage tours. For example, at key centenaries of Heroic Age events, particularly in the Ross Sea, cultural heritage featured in marketing though the tourism practices themselves did not change much in terms of sites visited. Moreover, separation between the cultural and the natural does not appear especially important to either providers or customers. This, in turn, is in keeping with our reading of archival records relating to the HSMs, which do not form a priority issue in the public record of ATCMs. Pulling these strands together suggests that a more nuanced understanding is needed about the perception of Antarctic heritage within the tourism industry and the ATS.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to Ieuan Hopkins, Archives Manager at the British Antarctic Survey for reviewing visitor books from Port Lockroy, Damoy Hut and Wordie House. The support of the UK Antarctic Heritage Trust and the New Zealand Antarctic Heritage Trust in permitting access to the visitor books for the research is gratefully acknowledged. We also thank Chrissy Emeny, Andrea Herbert, Adele Jackson, Emily McGeorge, Ursula Rack and Gabriela Roldán for looking at visitor books in Antarctica during the 2019–20 season. Adele Jackson’s sound advice was much appreciated. Advice from the two anonymous reviewers and the Editor to improve the manuscript are gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abercrombie and Kent. (2020a). Retrieved April 4, 2020, from https://www.abercrombiekent.com/tours/inspiring-expeditions-by-geoffrey-kent/2020/emperors-and-the-south-pole

- Abercrombie and Kent. (2020b). Retrieved April 4, 2020, from https://www.abercrombiekent.com/tours/luxury-expedition-cruises/2020/antarctic-discovery-palmers-bicentennial-expedition

- Amelung, B., & Lamers, M. (2006). Scenario development for Antarctic tourism: Exploring the uncertainties. Polarforschung, 75(2/3), 133–139.

- Antarctica 21. (2020). Retrieved April 4, 2020, from https://antarctica21.com

- ATCM. (2019a). Information Paper 11. Antarctic Tourism Workshop, 3-5 April; Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Chair’s Report. Buenos Aires: Antarctic Treaty Secretariat.

- ATCM. (2019b). Information Paper 139. Report of the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators 2018-19. Antarctic Treaty Secretariat.

- ATCM. (2019c). Information Paper 140. IAATO Overview of Antarctic tourism: 2018-19 season and preliminary estimates for the 2019-29 season. Antarctic Treaty Secretariat.

- ATCM. (2019d). Information Paper 142. Report on IAATO operator use of Antarctic Peninsula landing sites and ATCM Visitor Site guidelines, 2018-19 season. Antarctic Treaty Secretariat.

- ATCM. (2019e). Information Paper 145. A catalogue of IAATO operator activities. Antarctic Treaty Secretariat.

- ATCM. (2019f). Measure 12. Revised list of Antarctic Historic sites and Measures: The wreck of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s vessel endurance and C. A. Larsen multiexpedition cairn. Antarctic Treaty Secretariat.

- ATCM. (2019g). Resolution 2. Site Guidelines for visitors. Antarctic Treaty Secretariat.

- ATCM. (2019h). Resolution 3. Visitor Site Guidelines assessment and review checklist. Antarctic Treaty Secretariat.

- ATCM (Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting). (2018). Resolution 2. Guidelines for the assessment and management of heritage in Antarctica. Antarctic Treaty Secretariat.

- Barr, S. (2018). Twenty years of protection of historic values in Antarctica under the Madrid protocol. The Polar Journal, 8(2), 241–264. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2018.1541547

- Bass, D., Wells, F., & Ridgeway, R. (1986). Seven summits. Warner Books.

- Bender, N. A., Crosbie, K., & Lynch, H. J. (2016). Patterns of tourism in the Antarctic Peninsula region: A 20-year analysis. Antarctic Science, 28(3), 194–203. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954102016000031

- BPU Ltd. (2018). Report of the Trustees and Financial Reports for the Financial Year ended 30 April 2018 for the United Kingdom Antarctic Heritage Trust. https://www.ukaht.org/media/3567/year-end-report-2017-18.pdf

- Brooks, S. T., Jabour, J., van den Hoff, J., & Bergstrom, D. M. (2019). Our footprint on Antarctica competes with nature for rare ice-free land. Nature Sustainability, 2(3), 185–190. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0237-y

- Cruise Critic. (2020). New Expedition and Adventure Ships On Order. https://www.cruisecritic.com.au/articles.cfm?ID=3014&fbclid=IwAR3RzDScyZiByYN-6cMKtv3uWUzktgJO0MpHnicVxRumEtGRn8_eTkENPkY

- Cruise Industry News. (2018). Antarctica Tourism Numbers Surge https://www.cruiseindustrynews.com/cruise-news/18920-antarctica-tourism-numbers-surge.html

- Davis, P. B. (1995). Wilderness visitor management and Antarctic tourism (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Cambridge.

- de la Barre, S. (2013). Wilderness and cultural tour guides, place identity and sustainable tourism in remote areas. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(6), 825–844. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.737798

- Dodds, K., Hemmings, A. D., & Roberts, P. (Eds.). (2017). Handbook on the politics of Antarctica. Edward Elgar.

- Elmes, M., & Frame, B. (2008). Into Hot Air: A critical perspective on everest. Human Relations, 61(2), 213–241. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726707087785

- Explorers Grand Slam. (2020). Retrieved April 4, 2020, from www.explorersgrandslam.com

- Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language. Longman.

- Frame, B., & Hemmings, A. D. (2020). Coronavirus at the end of the world: Antarctica matters. Social Sciences and Humanities Open, 2(1), https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100054

- Frame, B., Leane, E., & Lindeman, R. W. (2018). Geocaching in Antarctica: Heroic exploration for the digital Era? The Polar Journal, 8(2), 397–406. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2018.1541839

- Geocaching. (2020). GC4TM62. Retrieved April 4, 2020, from https://www.geocaching.com/geocache/GC4TM62_base-a-port-lockroy?guid=d41256ae-6c4b-436e-9d35-d8db39bbe023

- Harrison, R. (2013). Heritage: Critical approaches. Routledge.

- Heritage Expeditions. (2020). Retrieved April 4, 2020, from https://www.heritage-expeditions.com/trip/east-antarctica-wake-mawson-15-dec-2019/

- Hernández, J. M., Kirilenko, A. P., & Stepchenkova, S. (2018). Network approach to tourist segmentation via user generated content. Annals of Tourism Research, 73, 35–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.09.002

- Hudson, S., & Thal, K. (2013). The impact of social media on the consumer decision process: Implications for tourism marketing. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(1-2), 156–160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2013.751276

- Huettmann, F. (Ed.). (2012). Protection of the three Poles. Springer.

- Hughes, J. (1994). Antarctic Historic Sites: the tourism implications. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(2), 284–294. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)90045-0

- IAATO a. (n.d). Visitor Statistics Downloads. https://iaato.org/information-resources/data-statistics/visitor-statistics/visitor-statistics-downloads/

- IAATO b. (n.d.). Retrieved April 4, 2020, from https://iaato.org/documents/10157/2305849/IAATO+News+Release+annual+meeting+opens+2018+FINAL.pdf/b3d9e66a-1974-4db9-b410-18250bd434fb

- Kirby, V. G., Stewart, E. J., & Steel, G. D. (2001). Thinking about Antarctic heritage: Kaleidoscopes and filters. Landscape Research, 26(3), 189–202. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01426390124137

- Leane, E. (2012). Antarctica in fiction: Imaginative narratives of the Far south. Cambridge University Press.

- Leihy, R. I., Coetzee, B. W. T., Morgan, F., Raymond, B., Shaw, J. D., Terauds, A., Bastmeijer, K., & Chown, S. L. (2020). Antarctica’s wilderness fails to capture continent’s biodiversity. Nature, 583(7817), 567–571. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2506-3

- Leiper, N. (1990). Tourist attraction systems. Annals of Tourism Research, 17(3), 367–384. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(90)90004-B

- Liggett, D., Frame, B., Gilbert, N., & Morgan, F. (2017). Is it all going south? Four future scenarios for Antarctica. Polar Record, 53(5), 459–478. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247417000390

- Liggett, D., McIntosh, A., Thompson, A., Gilbert, N., & Storey, B. (2011). From frozen continent to tourism hotspot? Five decades of Antarctic tourism development and management, and a glimpse into the future. Tourism Management, 32(2), 357–366. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.03.005

- Liggett, D., & Stewart, E. J. (2017a). Sailing in icy waters: Antarctic cruise tourism development, regulation and management. In C. Weeden & R. Dowling (Eds.), Cruise ship tourism (pp. 2nd ed.). wallingford (pp. 484–504). CABI.

- Liggett, D., & Stewart, E. J. (2017b). The changing face of political engagement in Antarctic tourism. In K. Dodds, A. D. Hemmings, & P. Roberts (2017).

- Lindström, K., et al. (2021). Historic sites and monuments and the crafting of a (cultural?) heritage regime in the Antarctic Treaty System, 1961-1972. Polar Geography, (to follow).

- Lintott, B. (2018). Antarctica: Human heritage on the continent of peace and science. ICOMOS: Proceedings of the 2017 ICOMOS General Assembly. ICOMOS India.

- MacCannell, D. (1976). The tourist. A new theory of the leisure class. Schocken Books.

- Manhire, B. (Ed.). (2004). The wide White page: Writers imagine Antarctica. Victoria University Press.

- Marine-Roig, E., & Clavé, S. A. (2015). Tourism analytics with massive user-generated content: A case study of barcelona. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 4(3), 162–172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.06.004

- Nielsen, H. (2017). Selling the south: commercialisation and marketing of Antarctica. In K. Dodds, A. D. Hemmings, & P. Roberts (2017).

- Noble, A. (2011). Ice blink: An Antarctic imaginary. Clouds Press.

- Noble Caledonia. (2020). Retrieved April 4, 2020, from https://www.noble-caledonia.co.uk/destinations/antarctic/tour/1921/in-the-wake-of-shackleton/?search_url_id=0https://www.wildearth-travel.com/trip/antarctica-explorers-and-kings-ocean-diamond/

- Oceanwide Expeditions. (2020). Retrieved April 4, 2020, from https://oceanwide-expeditions.com/antarctica/cruises/otl27-20-ross-sea-incl-helicopters

- Powell, R., Brownlee, M., Kellert, S. R., & Ham, S. H. (2012). From awe to satisfaction: Immediate affective responses to the Antarctic tourism experience. Polar Record, 48(2), 145–156. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247410000720

- Powell, R. B., Kellert, S. R., & Ham, S. H. (2008). Antarctic tourists: Ambassadors or consumers? Polar Record, 44(3), 236–241. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247408007456

- Powell, R. B., Ramshaw, G. P., Ogletree, S. S., & Krafte, K. E. (2016). Can heritage resources highlight changes to the natural environment caused by climate change? Evidence from the Antarctic tourism experience. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 11(1), 71–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2015.1082571

- Prasad, P. (2017). Crafting qualitative research: Beyond positivist traditions. Taylor & Francis.

- Quark Expeditions. (2020). Retrieved April 4, 2020, from https://www.quarkexpeditions.com/en/antarctic/expeditions/antarctic-express-fly-the-drake

- Read, R. (2018). Antarctica tourism is heating up. This is bad news for ice. https://www.ozy.com/acumen/antarctica-tourism-is-heating-up-this-is-bad-news-for-ice/89163

- Roura, R. (2012). Being there: Examining the behaviour of Antarctic tourists through their blogs. Polar Research, 31(1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3402/polar.v31i0.10905

- Roura, R. (2017). Antarctic cultural heritage: Geopolitics and management. Handbook on the Politics of Antarctica, 468, 484.

- Roura, R. M. (2009). Cultural heritage, tourism narratives, and tourism impacts: A case study of the airship mooring mast at Ny-Ålesund, svalbard. Téoros, 28(1), 29–38. Special Issue on Polar Tourism, May 2009. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7202/1024834ar

- Roura, R. M. (2011). The footprint of polar tourism: tourist behaviour at cultural heritage sites in Antarctica and Svalbard. Circumpolar Studies, No. 7. Eelde, Netherlands: Barkhuis.

- Russell, I. (2010). Heritages, identities and roots: A critique on arborescent models of heritage and identity. In G. S. Smith, P. M. Messenger, & H. A. Soderland (Eds.), Heritage values in contemporary society (pp. 29–41). Left Coast Press.

- Schillat, M., Jensen, M., Vereda, M., Sánchez, R. A., & Roura, R. (2016). Tourism in Antarctica: A multidisciplinary view of new activities carried out on the white continent. Springer.

- Senatore, M. X. (2019a). Assessing tourism patterns in the South Shetland Islands for the conservation of 19th-century archaeological sites in Antarctica. Polar Record, 55(3), 154–168. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247419000391

- Senatore, M. X. (2019b). Archaeologies in Antarctica from nostalgia to capitalism: A review. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 23(3), 755–771. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-019-00499-7

- Smith, L. (2006). Uses of heritage. Routledge.

- Stewart, E. J. & Liggett, D. (2018). Polar tourism: Status, trends, futures. In M. Nuttall, T. R. Christensen, & M. J. Siegert (Eds.), The routledge handbook of the polar regions (pp. 357–370). London: Routledge. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315730639-28.

- Student, J., Amelung, B., & Lamers, M. (2016). Towards a tipping point? Exploring the capacity to self-regulate Antarctic tourism using agent-based modelling. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(3), 412–429. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1107079

- Summerson, R., & Tin, T. (2018). Twenty years of protection of wilderness values in Antarctica. The Polar Journal, 8(2), 265–288. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2018.1541548

- van der Zee, E., Bertocchi, D., & Vanneste, D. (2018). Distribution of tourists within urban heritage destinations: A hot spot/cold spot analysis of TripAdvisor data as support for destination management. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1491955

- Wainschenker, P., & Leane, E. (2019). The ‘alien’ next door: Antarctica in South American fiction. The Polar Journal, 9(2), 324–339. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2019.1685178

- Waterton, E., Smith, L., & Campbell, G. (2006). The utility of discourse analysis to Heritage Studies: The burra charter and social inclusion. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 12(4), 339–355. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250600727000

- White Desert. (2020). Retrieved April 4, 2020, from http://www.white-desert.com

- Wild Earth Travel. (2020a). Retrieved April 4, 2020, from https://www.wildearth-travel.com/trip/antarctica-and-climate-change/

- Wild Earth Travel. (2020b). Retrieved April 4, 2020, from https://www.wildearth-travel.com/trip/antarctica-explorers-and-kings-ocean-diamond/

- Xiang, Z., & Gretzel, U. (2010). Role of social media in online travel information search. Tourism Management, 31(2), 179–188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.02.016

- Zeng, B., & Gerritsen, R. (2014). What do we know about social media in tourism? A review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 10, 27–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2014.01.001